A report by The Rt Hon the Baroness Hallett DBE Chair of the UK Covid-19 Inquiry

Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 26 of the Inquiries Act 2005

Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 18 July 2024

HC 18

| Figure | Description |

|---|---|

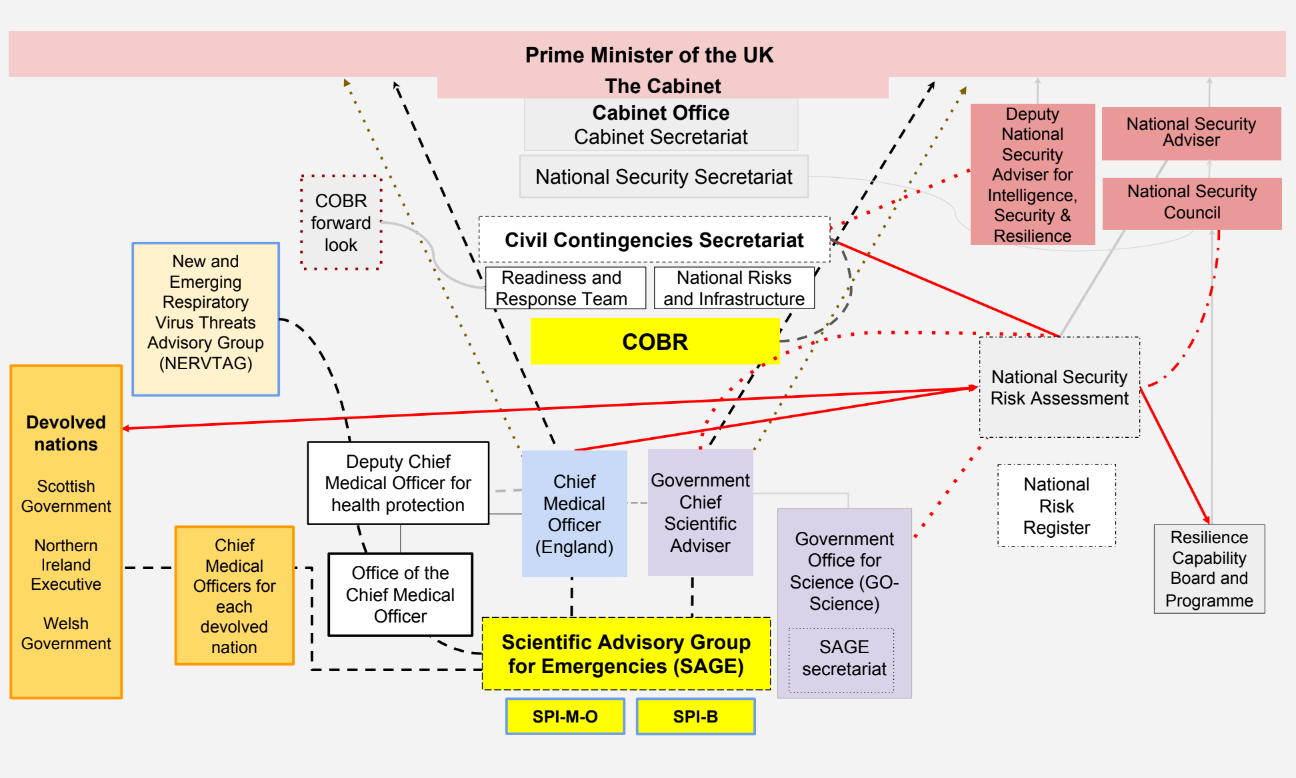

| Figure 1 | Pandemic preparedness and response central government structures in the UK and England - c. August 2019 |

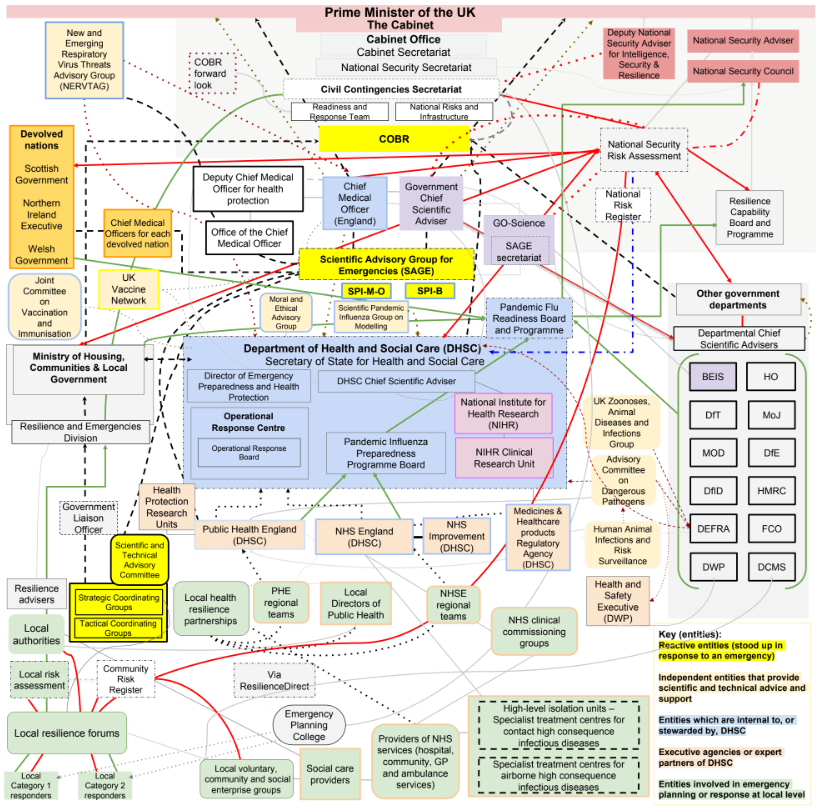

| Figure 2 | Pandemic preparedness and response structures in the UK and England – c. August 2019 |

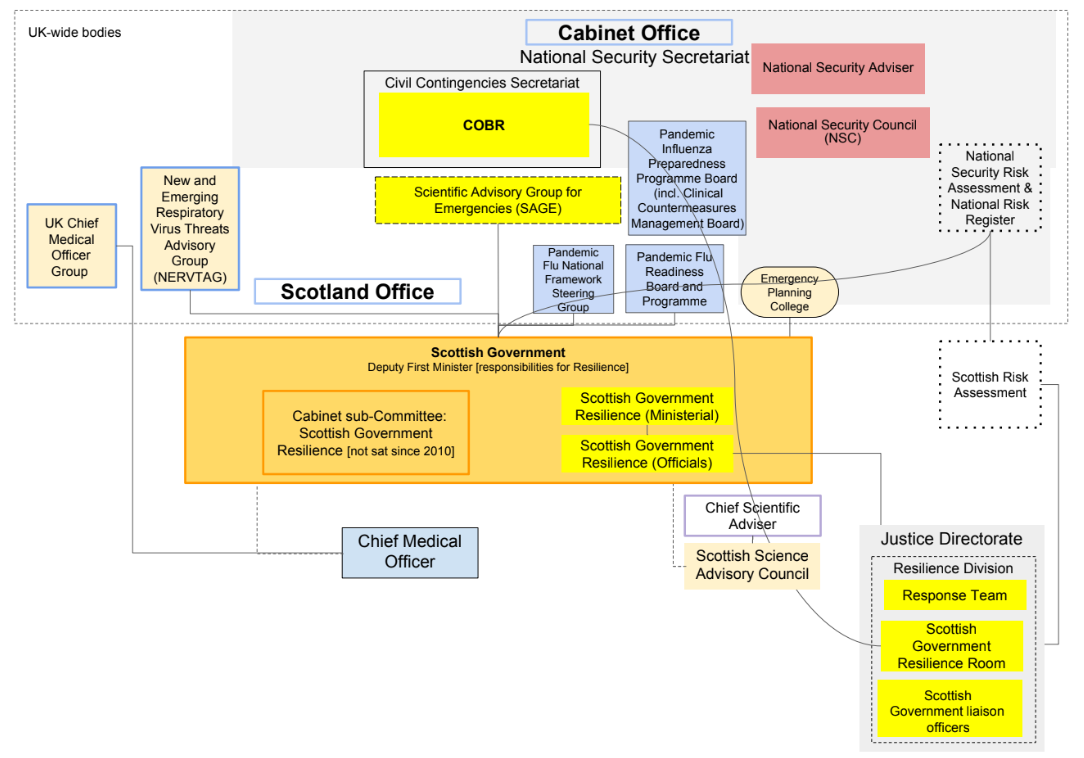

| Figure 3 | Pandemic preparedness and response central government structures in Scotland – c. 2019 |

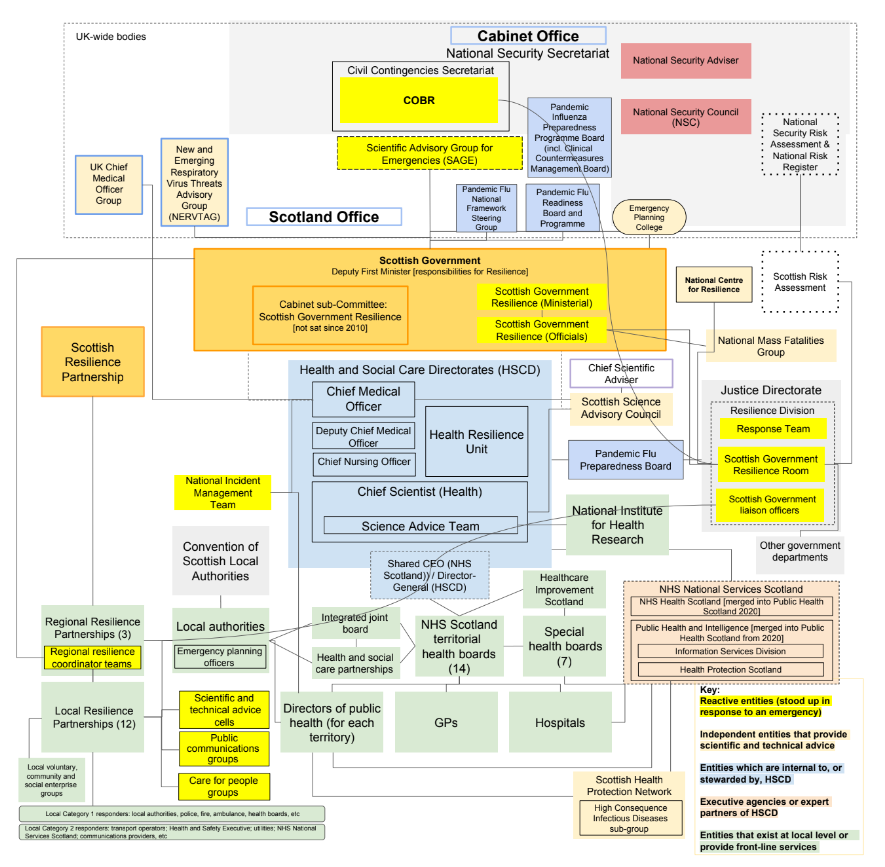

| Figure 4 | Pandemic preparedness and response structures in Scotland – c. 2019 |

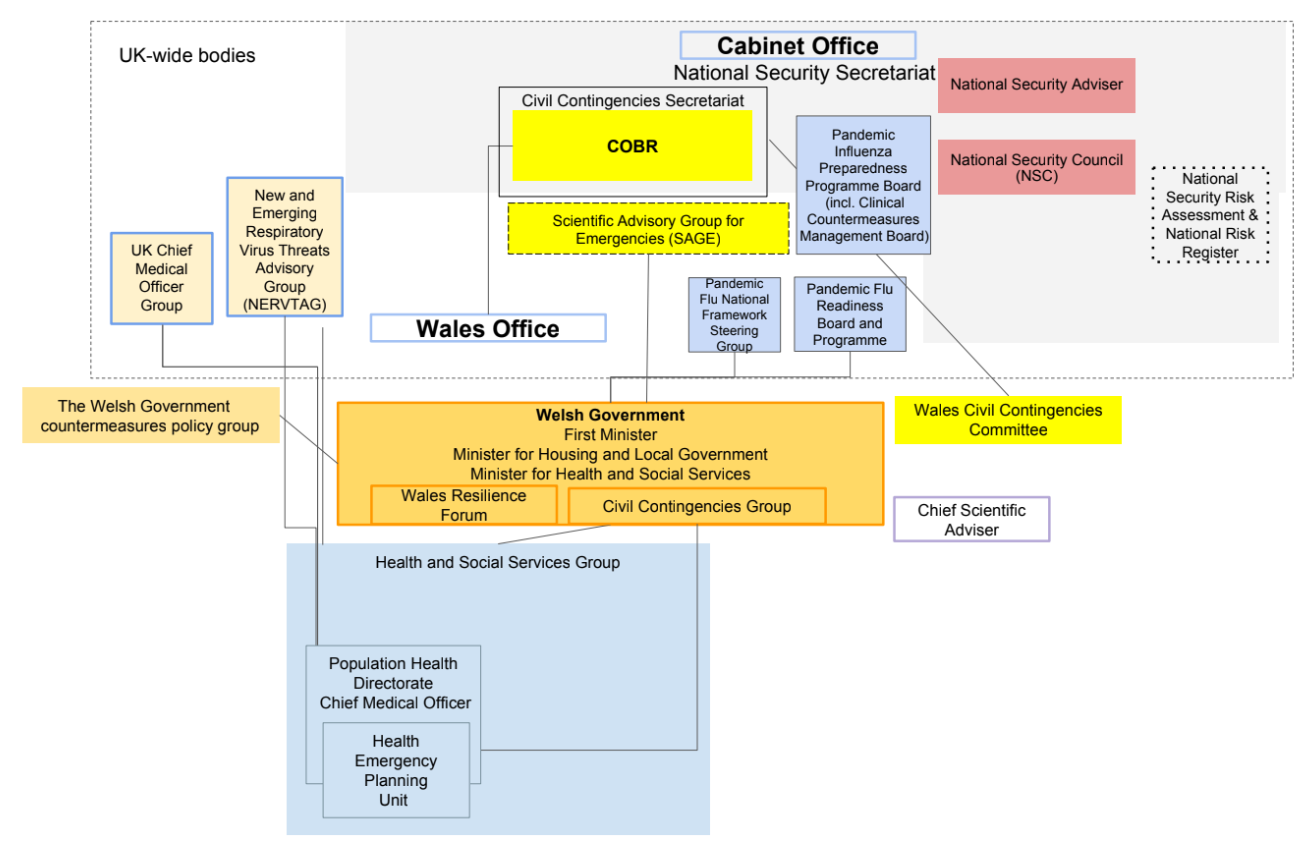

| Figure 5 | Pandemic preparedness and response central government structures in Wales – c. 2019 |

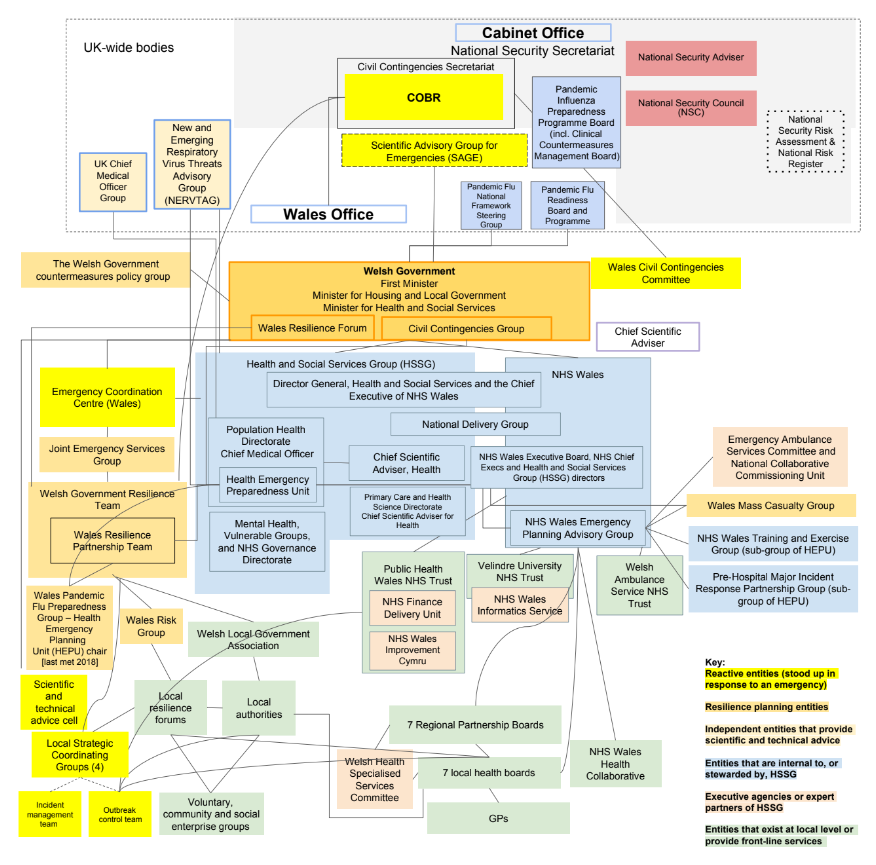

| Figure 6 | Pandemic preparedness and response structures in Wales – c. 2019 |

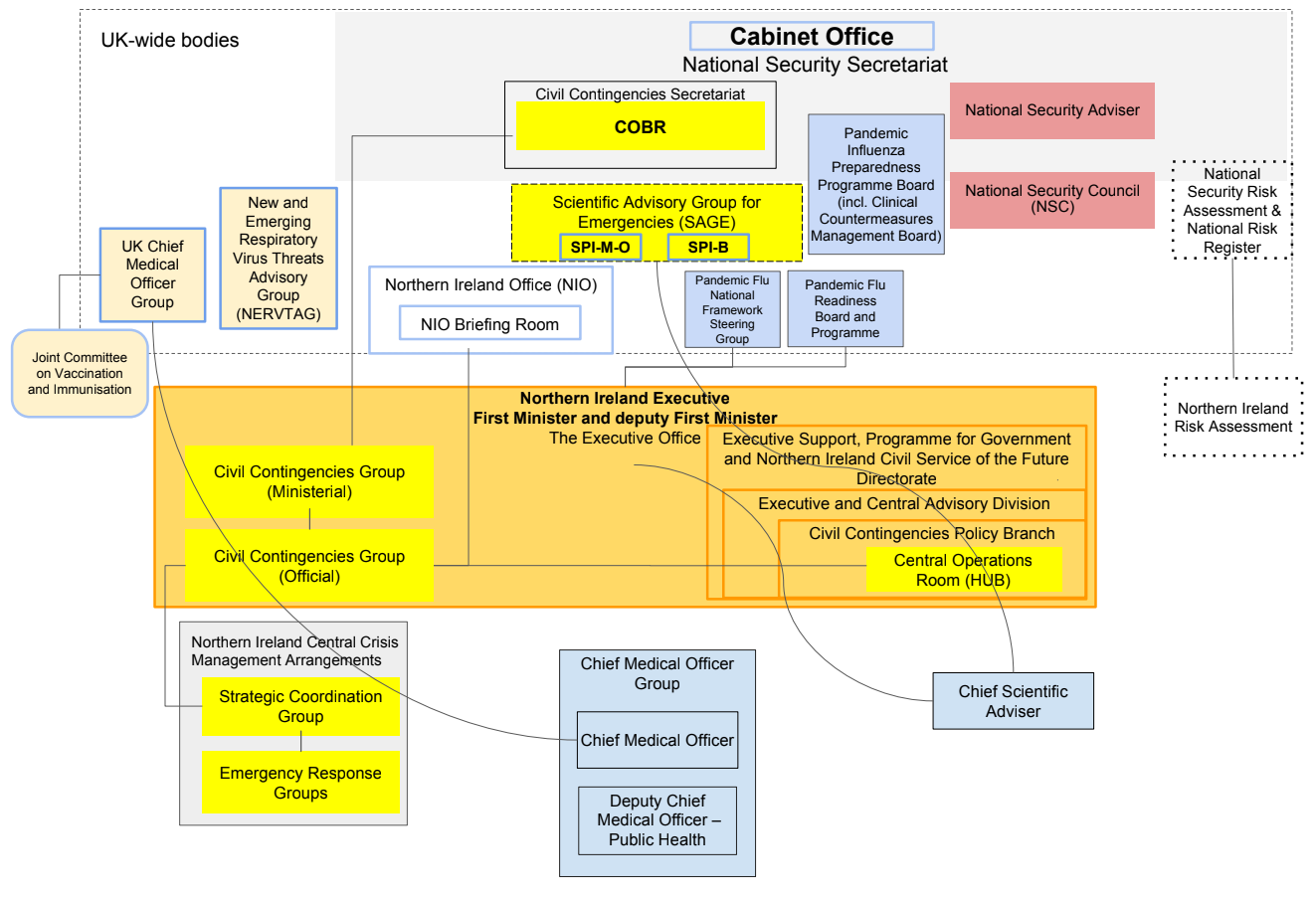

| Figure 7 | Pandemic preparedness and response central executive structures in Northern Ireland – c. 2019 |

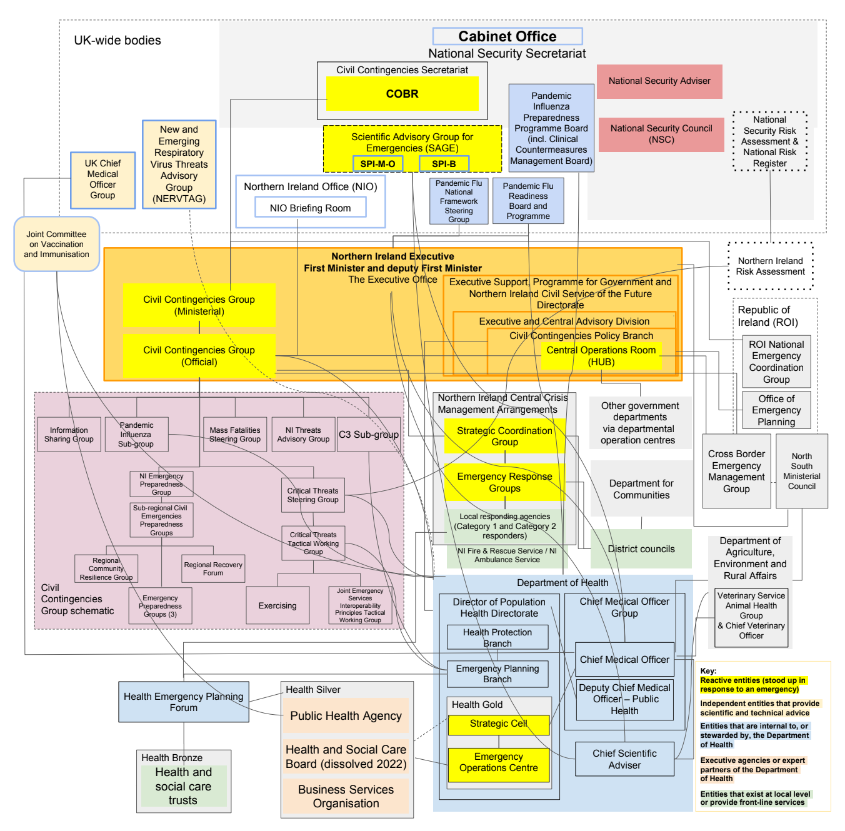

| Figure 8 | Pandemic preparedness and response structures in Northern Ireland – c. 2019 |

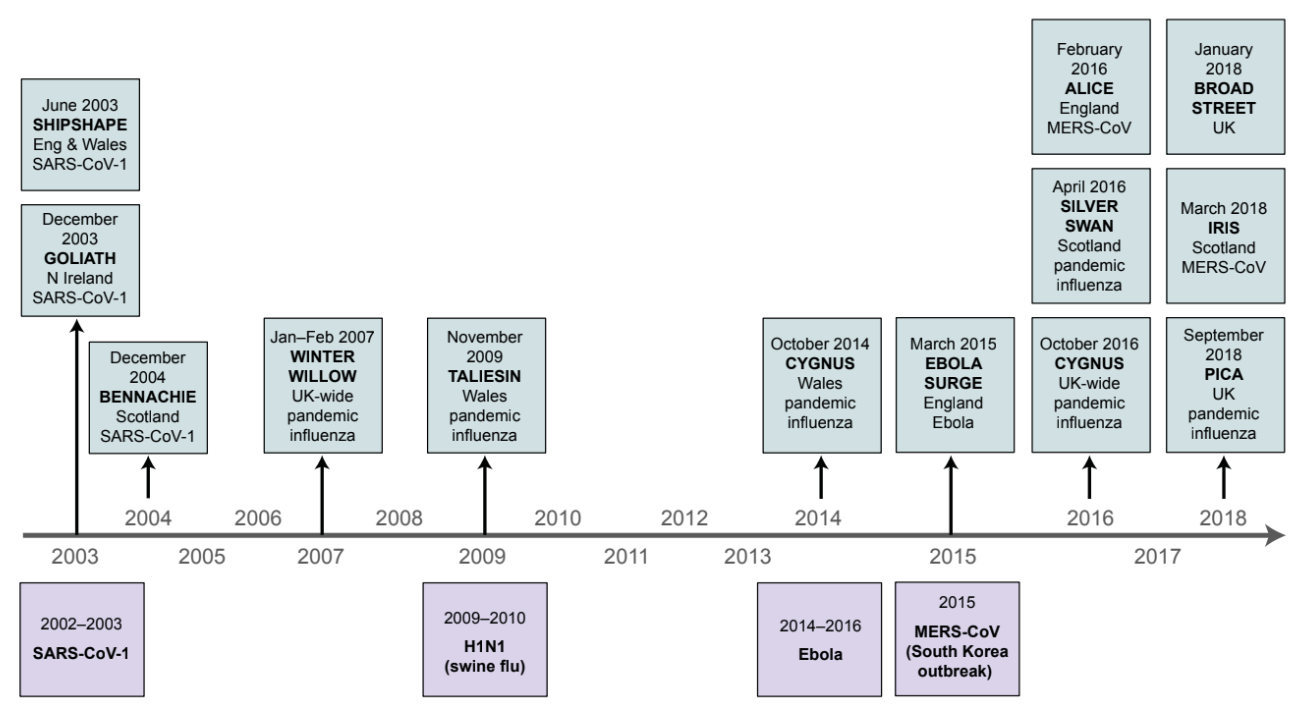

| Figure 9 | A timeline of key exercises undertaken between 2003 and 2018 |

| Table | Description |

|---|---|

| Table 1 | Summary of past major epidemics and pandemics |

| Table 2 | Reasonable worst-case scenarios from UK risk assessments in 2014, 2016 and 2019 |

| Table 3 | Module 1 Core Participants |

| Table 4 | Module 1 expert witnesses |

| Table 5 | Module 1 witnesses from whom the Inquiry heard evidence |

| Table 6 | Module 1 Counsel team |

| Table 7 | Key simulation exercises relevant to pandemic preparedness and resilience |

Introduction by The Rt Hon the Baroness Hallett DBE

This is the first report of the UK Covid-19 Inquiry. It examines the state of the UK’s central structures and procedures for pandemic emergency preparedness, resilience and response.

The primary duty of the state is to protect its citizens from harm. It is, therefore, the state’s duty to ensure that the UK is as properly prepared to meet threats from a lethal disease as it is from a hostile force. Both are threats to national security.

In this case, the threat came from a novel and potentially lethal virus. In late December 2019, a cluster of cases of pneumonia of an unknown origin were detected in the city of Wuhan in the Hubei province of China. A new virus, a strain of coronavirus, was subsequently identified and named as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The viral pathogen SARS-CoV-2 and the disease that it caused, Covid-19, spread across the globe.

It killed millions of people worldwide and infected many millions more. As at March 2024, the World Health Organization stated that there had been more than 774 million confirmed cases and over 7 million deaths reported globally, although the true numbers are likely to be far higher. The Covid-19 pandemic caused grief, untold misery and economic turmoil. Its impact will be felt for decades to come.

The impact of the disease did not fall equally. Research suggests that, in the UK, mortality rates were significantly higher among people with a physical or learning disability and people with pre-existing conditions, such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, heart disease, high blood pressure and diabetes. People from some ethnic minority groups and those living in deprived areas had a significantly higher risk of being infected by Covid-19 and dying from it.

Beyond the individual tragedy of each and every death, the pandemic placed extraordinary levels of strain on the UK’s health, care, financial and educational systems, as well as on jobs and businesses.

As in many other countries, the UK government and the governments of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland were required to take serious and far-reaching decisions about how to contain and respond to the virus. The 23 March 2020 decision to implement a legally enforced ‘stay at home’ order was hitherto unimaginable.

The life of the UK was severely curtailed as the majority of its citizens were confined to home. Almost every area of public life across all four nations was badly affected. The hospitality, retail, travel and tourism, arts and culture, and sport and leisure sectors effectively ceased to operate. Even places of worship closed.

Levels of mental illness, loneliness, deprivation and exposure to violence at home surged. Children missed out on academic learning and on precious social development.

The cost, in human and financial terms, of bringing Covid-19 under control has been immense. Government borrowing and the cost of procurement and of the various job retention, income, loan, sick pay and other support schemes have severely impacted public finances and the UK’s financial health.

The impact on the NHS, its operations, its waiting lists and on elective care has been similarly immense. Millions of patients either did not seek or did not receive treatment and the backlog for treatment has reached historically high levels.

Societal damage has been widespread, with existing inequalities exacerbated and access to opportunity significantly weakened.

Ultimately, the UK was spared worse by the individual efforts and dedication of health and social care workers and the civil and public servants who battled the pandemic; by the scientists, medics and commercial companies who researched valiantly to produce life-saving treatments and ultimately vaccines; by the local authority workers and volunteers who looked after and delivered food and medicine to elderly and vulnerable people, and who vaccinated the population; and by the emergency services, transport workers, teachers, food and medicinal industry workers and other key workers who kept the country going.

Unfortunately, the expert evidence suggests that they will be called upon again. It is not a question of ‘if’ another pandemic will strike but ‘when’. The evidence is overwhelmingly to the effect that another pandemic – potentially one that is even more transmissible and lethal – is likely to occur in the near to medium future. Unless the lessons are learned, and fundamental change is implemented, that effort and cost will have been in vain when it comes to the next pandemic.

There must be radical reform. Never again can a disease be allowed to lead to so many deaths and so much suffering.

It is into these extreme events and consequences that it is my duty to inquire. In May 2021, then Prime Minister Boris Johnson MP announced his decision to establish a statutory inquiry to examine the UK’s preparedness and response to the Covid-19 pandemic and learn lessons for the future. I was appointed Chair of the Inquiry in December 2021.

The extremely broad Terms of Reference for this Inquiry were drawn up following formal consultation between the Prime Minister and the First Ministers of Scotland and Wales and the First Minister and deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland. There was then an extensive public consultation process.

I consulted widely across all four nations, visiting towns and cities in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland and speaking, in particular, to a number of bereaved people. In parallel, the Inquiry team met with representatives of more than 150 organisations in ‘roundtable’ discussions. In total, the Inquiry received more than 20,000 responses to the consultation.

In light of the views expressed, the Inquiry recommended a number of significant changes to the draft Terms of Reference. These were accepted in full and included explicit acknowledgement of the need to hear about people’s experiences and to consider any disparities in the impact of the pandemic.

The unprecedented width and scope of the Terms of Reference therefore commanded public support.

I also sought an express mandate to publish interim reports so as to ensure that any urgent recommendations could be published and considered in a timely manner. It is plainly in the public interest that effective recommendations are made as quickly as possible to ensure that proper emergency preparedness and resilience structures and systems are in place before the next pandemic or national civil emergency.

The Terms of Reference reflect the unprecedented complexity of this Inquiry. It is not an inquiry limited in scope by a single event, a short passage of time or a single policy or finite course of government or state conduct. It is an inquiry into how the gravest and most multi- layered peacetime emergency struck an entire country (in fact, four countries) and how the UK government and devolved administrations responded, across almost the entire range of their decision-making and public functions. The pandemic and the response spared no part of British life and so there is almost no part of that life excluded from our investigations.

I was determined from the outset that this Inquiry would not drag on for years and produce a report or reports long after they had lost any relevance. The Inquiry has therefore proceeded at great pace.

On 21 July 2022, about five months following the ending of Covid-19 legal restrictions on the population of the UK, the Inquiry was formally opened. I also announced the decision to conduct the Inquiry in modules. The first public hearing, Module 1 (Resilience and preparedness), took place less than a year later, between 13 June and 20 July 2023.

The hearing was preceded by an extensive and complex process of obtaining under compulsion potentially relevant documents from a wide range of sources. This material was then examined by the Inquiry team, and more than 18,000 documents were deemed to be relevant and were disclosed to the Core Participants to assist them in their preparation for the hearing.

The Module 1 Inquiry team obtained more than 200 witness statements and called 68 factual and expert witnesses from the UK government, the devolved administrations, resilience and health structures, civil society groups and groups representing bereaved people.

The public hearing for Module 2 (Core UK decision-making and political governance) then took place between 3 October and 13 December 2023. The analogous public hearings into the core political and administrative decision-making of the Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish governments took place, respectively, between 16 January and 1 February 2024, 27 February and 14 March 2024, and 30 April and 16 May 2024.

As at the publication date of this Report, Module 3 (Impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on healthcare systems in the four nations of the UK), Module 4 (Vaccines and therapeutics), Module 5 (Procurement), Module 6 (Care sector), Module 7 (Test, trace and isolate), Module 8 (Children and young people) and Module 9 (Economic response) have all been formally opened and are in the course of being prepared for public hearings. There will also be further hearings into the impact that the pandemic and the response had on various aspects of British life.

No inquiry with such a wide scope has ever proceeded with such speed or rigour, or obtained so much relevant documentation in such a relatively limited amount of time. It is right to say that few countries have established formal legal inquiries investigating the many aspects of the Covid-19 pandemic, let alone inquiries of this scale. A number of countries, such as Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Australia, have instead instituted independent commissions led by experts in epidemiology, public health, economics and public policy. Such research commissions may be quicker and cheaper than a UK statutory inquiry, but they are not necessarily legal processes with the force of the law behind them. Most do not have the powers to compel the production of evidence or the giving of sworn testimony by political and administrative leaders; they are not open to public scrutiny in the same way as this Inquiry; they do not allow bereaved people and other interested groups to participate meaningfully in the process as legal core participants; and they do not have anything like the same scope or depth.

It may be thought therefore that a statutory inquiry with extensive powers was the right and only appropriate vehicle for an inquiry considering a national crisis of such scale and intensity, and one involving so much death and suffering. The people of the UK, but especially bereaved people and those who have otherwise suffered harm, need to know whether anything could reasonably have been done better.

If the Inquiry’s recommendations are implemented, the risk of loss and suffering in the future will be reduced, and policy-makers, faced with extraordinarily difficult decisions, will be assisted in responding to a crisis.

I want to express my gratitude to all those who have given so much of their time and resources in providing the Inquiry with the voluminous amount of documentary material, to the many people who have provided their assistance through the provision of written statements and sworn evidence, and to all who have shared their experience of the pandemic with the Inquiry through its listening exercise, Every Story Matters. I would also like to thank the Module 1 team (both secretariat and legal) without whose extraordinarily hard work the Module 1 hearings and this Report would not have been possible.

I am also very grateful to the Core Participants and their legal teams, especially the groups representing bereaved people, for their insightful and conscientious contribution to the Inquiry process. The determination and drive of their clients and representatives, and the skill and experience of their legal teams, continue to be of invaluable assistance to me and to the Inquiry team.

The harrowing testimony of loss and grief given by the bereaved witnesses and others who suffered during the pandemic provided a salutary confirmation of the purpose of this Inquiry.

The Rt Hon the Baroness Hallett DBE

18 July 2024

Voices of those bereaved

Dad was an incredibly popular man, and it was a source of great pain for everybody that knew him that they would not be able to attend his funeral. Only ten people were allowed there on the day, all had to be socially distanced, due to those limitations, and as an illustration of how popular my dad was and the impact that he had on the people around him, over 300 people lined the streets for the procession ... In my dad’s case, we were offered the chance to have a phone call – I say a phone call, a video call with my dad in hospital to say our goodbyes, which is something that I didn’t take the hospital up on, as that’s not how I want to remember my dad. Some of the last photos I had of him are him sitting in his hospital bed wearing his oxygen mask and I would prefer not to remember him like that and instead to remember him how he was in life.”¹

“It was actually five days from the onset of Covid until she died ... in that time the Covid destroyed her lungs, her kidneys, her liver and her pancreas. They tried to give her dialysis, but the Covid had made her blood so thick and sticky that it actually blocked the dialysis machine ... they told her and myself that she wasn’t a candidate for ICU [intensive care unit] and intubation and told us both that she was dying, and there was nothing, sadly, that they could do to help her ... it was the terrible decisions you had to make about who could go and who couldn’t, and of course if someone had been with their loved one at the end, they were often told by some hospitals, ‘You have a choice: you can either come in and be with them at the end or you can go to the funeral, but you can’t do both, because you have to be in isolation.’”²

“Something that was not communicated to us was that once somebody with Covid dies, they are almost treated like toxic waste. They are zipped away and you – nobody told us that you can’t wash them, you can’t dress them, you can’t do any of those things, the funerals, the ceremonies, you just can’t do any of those. You couldn’t sing at a funeral. You know, we’re Welsh, that’s something you have to do ... my dad did not have a good death. Most of our members’ loved ones did not have a good death ... when we left the hospital, my dad – we were given my dad’s stuff in a Tesco carrier bag. Some people were given somebody else’s clothes that were in a pretty awful state. It’s those things like that that don’t often get considered ... there is such a thing as a good death, and I think that was very overlooked during the pandemic ... there is a whole generation, my mum’s generation, who haven’t got the mechanisms like maybe I have to complain and question, and they are heartbroken and really in shock. You know, my mum cries daily and – even though it’s nearly three years ... it’s just – they’re just left with that feeling of nobody cared.”³

“When we took mummy up into the hospital, there was very limited – just a plastic apron on staff, and my sister actually asked about Covid, and we were told not to worry, it would be a flash in the pan and gone by the summer ... I am here to remind everybody of the human cost that we paid as bereaved people. My mummy was not cannon fodder. My mummy was a wonderful wee woman who had the spirit of Goliath, and I know she’s standing here with me today, because she would want me to be here, because she knows that she lived a life, as did all our loved ones, and it’s very important that we remember the human cost, because there are too many people out there now that think Covid has gone away. People are still losing their life to Covid.”⁴

Executive summary

In 2019, it was widely believed, in the UK and abroad, that the UK was not only properly prepared but was one of the best-prepared countries in the world to respond to a pandemic. This Report concludes that, in reality, the UK was ill prepared for dealing with a catastrophic emergency, let alone the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic that actually struck.

In 2020, the UK lacked resilience. Going into the pandemic, there had been a slowdown in health improvement, and health inequalities had widened. High pre-existing levels of heart disease, diabetes, respiratory illness and obesity, and general levels of ill-health and health inequalities, meant that the UK was more vulnerable. Public services, particularly health and social care, were running close to, if not beyond, capacity in normal times.

The Inquiry recognises that decisions as to the allocation of resources to prepare for a whole-system civil emergency fall exclusively to elected politicians. They must grapple with competing demands for public money and limited resources. It may be tempting for them to focus on the immediate problem before them rather than dwell on what may or may not happen. Proper preparation for a pandemic costs money. It involves preparing for an event that may never happen. However, the massive financial, economic and human cost of the Covid-19 pandemic is proof that, in the area of preparedness and resilience, money spent on systems for our protection is vital and will be vastly outweighed by the cost of not doing so.

Had the UK been better prepared for and more resilient to the pandemic, some of that financial and human cost may have been avoided. Many of the very difficult decisions policy-makers had to take would have been made in a very different context. Preparedness for and resilience to a whole-system civil emergency must be treated in much the same way as we treat a threat from a hostile state.

The Inquiry found that the system of building preparedness for the pandemic suffered from several significant flaws:

- The UK prepared for the wrong pandemic. The significant risk of an influenza pandemic had long been considered, written about and planned for. However, that preparedness was inadequate for a global pandemic of the kind that struck.

- The institutions and structures responsible for emergency planning were labyrinthine in their complexity.

- There were fatal strategic flaws underpinning the assessment of the risks faced by the UK, how those risks and their consequences could be managed and prevented from worsening, and how they could be responded to.

- The UK government’s sole pandemic strategy, from 2011, was outdated and lacked

adaptability. It was virtually abandoned on its first encounter with the pandemic. It focused on only one type of pandemic, failed adequately to consider prevention or proportionality of response, and paid insufficient attention to the economic and social consequences of pandemic response. - Emergency planning generally failed to account sufficiently for the pre-existing health and societal inequalities and deprivation in society. There was also a failure to appreciate the full extent of the impact of government measures and long-term risks, from both the pandemic and the response, on ethnic minority communities and those with poor health or other vulnerabilities, as well as a failure to engage appropriately with those who know their communities best, such as local authorities, the voluntary sector and community groups.

- There was a failure to learn sufficiently from past civil emergency exercises and outbreaks of disease.

- There was a damaging absence of focus on the measures, interventions and infrastructure required in the event of a pandemic – in particular, a system that could be scaled up to test, trace and isolate in the event of a pandemic. Despite reams of documentation, planning guidance was insufficiently robust and flexible, and policy documentation was outdated, unnecessarily bureaucratic and infected by jargon.

- In the years leading up to the pandemic, there was a lack of adequate leadership, coordination and oversight. Ministers, who are frequently untrained in the specialist field of civil contingencies, were not presented with a broad enough range of scientific opinion and policy options, and failed to challenge sufficiently the advice they did receive from officials and advisers.

- The provision of advice itself could be improved. Advisers and advisory groups did not have sufficient freedom and autonomy to express dissenting views and suffered from a lack of significant external oversight and challenge. The advice was often undermined by ‘groupthink’.

The Inquiry has no hesitation in concluding that the processes, planning and policy of the civil contingency structures within the UK government and devolved administrations and civil services failed their citizens.

The Module 1 Report recommends fundamental reform of the way in which the UK government and the devolved administrations prepare for whole-system civil emergencies. Although each recommendation is important in its own right, all the recommendations must be implemented in concert so as to produce the changes that the Inquiry judges to be necessary.

Later modules will specifically report and make recommendations in relation to the preparedness of three particular aspects of the UK’s preparedness and response structures: test, trace and isolate schemes; government stockpiles and procurement of personal protective equipment (PPE); and vaccine availability.

This first Report recommends, in summary, the following:

- Each government should create a single Cabinet-level or equivalent ministerial committee (including the senior minister responsible for health and social care) responsible for whole-system civil emergency preparedness and resilience, to be chaired by the leader or deputy leader of the relevant government. There should also be a single cross-departmental group of senior officials in each government to oversee and implement policy on civil emergency preparedness and resilience.

- The lead government department model for whole-system civil emergency preparedness and resilience is not appropriate and should be abolished.

- The UK government and devolved administrations should develop a new approach to risk assessment that moves away from reliance on reasonable worst-case scenarios towards an approach that assesses a wider range of scenarios representative of the different risks and the range of each kind of risk. It should also better reflect the circumstances and characteristics particular to England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and the UK as a whole.

- A new UK-wide whole-system civil emergency strategy should be put in place and it should be subject to a substantive reassessment at least every three years to ensure that it is up to date and effective, and incorporates lessons learned from civil emergency exercises.

- The UK government and devolved administrations should establish new mechanisms for the timely collection, analysis, secure sharing and use of reliable data for informing emergency responses, such as data systems to be tested in pandemic exercises. In addition, a wider range of ‘hibernated’ and other studies should be commissioned that are designed to be rapidly adapted to a new outbreak.

- The UK government and devolved administrations should hold a UK-wide pandemic response exercise at least every three years.

- Each government should publish a report within three months of the completion of each civil emergency exercise summarising the findings, lessons and recommendations, and should publish within six months of the exercise an action plan setting out the specific steps to be taken in response to the report’s findings. All exercise reports, action plans, emergency plans and guidance from across the UK should be kept in a single UK-wide online archive, accessible to all involved in emergency preparedness, resilience and response.

- Each government should produce and publish a report to their respective legislatures on whole-system civil emergency preparedness and resilience at least every three years.

- External ‘red teams’ should be regularly used in the Civil Service of the UK government and devolved administrations to scrutinise and challenge the principles, evidence, policies and advice relating to preparedness for and resilience to whole-system civil emergencies.

- The UK government, in consultation with the devolved administrations, should create a UK-wide independent statutory body for whole-system civil emergency preparedness, resilience and response. The body should provide independent, strategic advice to the UK government and devolved administrations, consult with the voluntary, community and social enterprise sector at a national and local level, as well as with directors of public health, and make recommendations.

Chapter 1: A brief history of epidemics and pandemics

Introduction

| 1.1. | To assess the state of a nation’s preparedness for a pandemic, one must first assess the nature of the risk, the likelihood of its occurring and the impact of the risk if it does occur. This chapter considers a brief history of epidemics and pandemics to put the likelihood and the possible impact into context. |

| 1.2. | Epidemics and pandemics have occurred throughout recorded human history.1 They were and remain a substantial and increasing risk to the safety, security and wellbeing of the UK.2 The coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic is estimated to have caused approximately 22 million excess deaths globally.3 Official UK figures put the number of deaths involving Covid-19 in the four nations of the UK at over 225,000 in June 2023.4 Nothing on this scale has been seen in more than a century. |

Past major epidemics and pandemics

| 1.3. | There is an inherent uncertainty and unpredictability about disease outbreaks, but the Covid-19 pandemic was not without precedent. As set out in Table 1, major epidemics and pandemics (an epidemic of an infection occurring worldwide or over a very wide area, usually affecting a large number of people) are far from unknown.5 |

| Time period | Pathogen | Disease (colloquial or common name) | Global cases (attack rate) | Global deaths | UK cases | UK deaths | Case fatality ratio* | Route of transmission | Asymptomatic infection widespread? | Probable origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1889 to 1894 | Uncertain. HCoV-OC43 or influenza | Russian flu | Became endemic (>90%)* | 1m* | Became endemic (>90%) | 132,000 | 0.1–0.28% | Respiratory | Unknown but probable | Central Asia |

| 1918 to 1920 | Influenza: H1N1 | Spanish flu | Became endemic (>90%) | 50m* | Became endemic (>90%) | 228,000 | 2.5–10% | Respiratory | Yes | USA (or, less likely, China/France) |

| 1957 to 1959 | Influenza: H2N2 | Asian flu | Became endemic (>90%)* | 1.1m | Became endemic (>90%)* | 5,000* | 0.017–0.1% | Respiratory | Yes | China |

| 1968 to 1970 | Influenza: H3N2 | Hong Kong flu | Became endemic (>90%) | 2m | Became endemic (>90%) | 37,500* | 0.1–0.2% | Respiratory | Yes | Hong Kong or China |

| 1977 to 1978 | Influenza: H1N1 | Russian flu | Became endemic (>90%) | 700,000 | Became endemic (>90%) | 6,000* | <0.1% | Respiratory | Yes | China or Russia (not zoonotic)* |

| 1981 onwards | Retrovirus: HIV | AIDS | 84.2m cumulative, 38.4m now (0.7%) | 40.1m | 165,338 | 25,296 | ~99% [untreated] | Blood-borne/sexual | Yes | West Central Africa (first detected USA) |

| 2002 to 2003 | Coronavirus: SARS-CoV-1 | SARS | 8,096 (<0.001%) | 774 | 4 | 0 | 9.6% | Respiratory | No | China |

| 2009 to 2010 | Influenza: H1N1 | Swine flu | Became endemic (first wave ~24%) [491,382 official]* | 284,000 [18,449 official] | Became endemic (>90%) [28,456 official]* | 457 [official] | 0.01–0.02% | Respiratory | Yes | Mexico (first detected USA) |

| 2012 onwards | Coronavirus: MERS-CoV | MERS | 2,519 (<0.001%) | 866 | 5 | 3 | 34.3% | Respiratory | Not initially, but more reports over time | Saudi Arabia |

| 2013 to 2016 | Ebola virus: EBOV | Ebola | 28,616 (<0.001%) | 11,310 | 3 | 0 | 62.9% | Contact | No | Guinea |

| 2019 onwards | Coronavirus: SARS-CoV-2 | Covid-19 | Becoming endemic as of 2023 (>90%) | 22m | Becoming endemic (>90%) [22m official] | 225,668 [official] | 0.67–1.18% [infection fatality ratio] | Respiratory | Yes | China |

All figures are approximate. They are estimates derived from published research available before 2020, apart from sources for SARS-CoV-2. Figures may not be strictly comparable and methodological quality varies. Asterisks denote particularly important caveats (see INQ000207453). Further details, including all caveats and references, are in the full table: INQ000207453.

| 1.4. | Two types of zoonotic pathogens are of particular concern when preparing for epidemics and pandemics: virus strains of pandemic influenza and coronaviruses. In addition, there is always the possibility of ‘Disease X’, a hypothetical emerging future pathogen currently not known to cause human disease with the potential to cause a pandemic, whatever its origins.⁶ Covid-19, when it emerged, was a ‘Disease X’.⁷ |

Pandemic influenza

| 1.5. | Pandemic influenza is caused by a novel influenza virus that is different from the usual circulating strains.⁸ It has caused repeated pandemics that have varied in terms of magnitude, severity and impact, and is notoriously difficult to predict.⁹ For example, the ‘Spanish flu’ pandemic of 1918 to 1920, which was caused by an H1N1 influenza strain, is estimated to have killed approximately 50 million people worldwide and 228,000 in the UK.¹⁰ The 2009 to 2010 H1N1 influenza pandemic (‘swine flu’), by contrast, had a significantly smaller impact than typical influenza seasons.¹¹ |

| 1.6. | Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, the focus of the UK’s pandemic preparedness and resilience was on influenza. This was and remains the single biggest predictable pathogen risk.¹² Although it was understandable for the UK to prioritise pandemic influenza, this should not have been to the effective exclusion of other potential pathogen outbreaks. These too have been increasing in number. |

Coronaviruses

| 1.7. | Coronaviruses in humans were seen only to be a relatively benign group of circulating viruses that caused mild respiratory illnesses (ie common colds) in the majority of people.¹³ It was not until late 2002 that human coronaviruses became a cause for global concern.¹⁴ Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is thought to have emerged from an animal in a live animal ‘wet market’ in the Guangdong province of China sometime in late 2002.¹⁵ It was the first new severe disease transmissible from person to person to emerge in the 21st century, and caused outbreaks in multiple countries.¹⁶ In June 2012, in Saudi Arabia, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) was first identified following transmission of the infection from camels to humans.¹⁷ In May 2015, a major outbreak of MERS-CoV occurred in healthcare facilities in South Korea when an infected person returned home from the Middle East.¹⁸ |

Outbreaks of disease

| 1.8. | There are a number of ways in which epidemics and pandemics may emerge. In humans, novel infectious diseases are predominantly caused by zoonotic spillover.¹⁹ This generally occurs when humans come into close contact with infected animals or animal products and a pathogen crosses the species barrier from animals to humans.²⁰ The world is teeming with organisms that have not yet found their way into the human population. Globally, there are thought to exist more than 1.5 million undescribed viruses in mammals and birds, of which about 750,000 are thought to have the potential to spill over into humans and cause epidemics.²¹ As of 2020, there were more than 200 known zoonotic pathogens.²² These range in impact from those that are completely harmless to humans to those with pandemic potential and devastating consequences. |

| 1.9. | Professor Jimmy Whitworth and Dr Charlotte Hammer, expert witnesses on infectious disease surveillance (see Appendix 1: The background to this module and the Inquiry’s methodology), explained that the possibility of novel pathogens making the leap from animals to humans had increased in recent decades.²³ This was due to a number of factors, including urbanisation and globalisation, which increase the likelihood of pathogens transmitting from one part of the world to another and the speed with which they will do so.²⁴ |

| 1.10. | The more interconnected the world becomes, the more likely it is that pathogens that emerge in one part of the world will spread to another.²⁵ The more ecological change and development there is at the interface between humans and the natural world, the greater the probability that pathogens will make the leap from animals to humans.²⁶ The more laboratories there are in the world that are involved in biological research, the more chance there is that leaks from laboratories will occur with ramifications for the population at large.²⁷ Increased instability between and within nations increases the biological security threat.²⁸ The risk of new pathogens arising and spreading in the human population is only likely to increase. The key characteristics of pathogens with pandemic potential are high adaptability, high transmissibility and becoming infectious before the host has developed symptoms or in the absence of any symptoms.²⁹ It is on those characteristics, as well as the critically important case fatality ratio, that the UK’s systems of preparedness and resilience should be focused. |

| 1.11. | Laboratory accidents and the malicious use of biological material are less frequent and less likely to be publicly acknowledged than zoonotic spillover, but their consequences may be just as lethal.³⁰ While novel pathogens are not the only potential biological or civil emergency risk faced by the UK, it is clear that the risk of pathogenic outbreaks must be taken very seriously by society and governments, and proper preparations made. |

| 1.12. | While the primary routes of transmission for pandemic influenza and coronaviruses are airborne and respiratory, there are – and will be in the future, including for novel pathogens – other potential routes of transmission.³¹ These may include: oral – through water or food (eg cholera and typhoid); vector-borne – carried by insects or arachnids (eg malaria and Zika virus); and contact – by touch (eg Ebola virus disease).³² Prior to Covid-19, the last major pandemic with significant mortality had been caused by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which has killed more than 40 million people worldwide to date and more than 25,000 people in the UK.³³ HIV’s route of transmission is sexual and intravenous. Before the availability of antiretroviral drugs, it had a mortality rate of nearly 100%.³⁴ |

| 1.13. | This puts into context the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19) and the Covid-19 pandemic. In the 20th century alone, the threat from epidemics and pandemics did not subside but increased. Novel infectious diseases are part of the landscape for emergency preparedness and resilience. Their emergence ought not to come as a surprise. |

| 1.14. | In the early 21st century, prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, the world had experienced four large outbreaks caused by high consequence human infectious diseases that stopped short of becoming global pandemics – three of which were caused by coronaviruses.³⁵ The UK scientific community had recognised that coronaviruses were a category of viruses that presented a “clear and present danger” that needed to be addressed.³⁶ The international scientific community had also warned of the dangers of emerging zoonotic infectious diseases – which had caused the majority of emerging infectious disease events in the previous six decades – and of the pandemic threat posed by high-impact respiratory pathogens.³⁷ A coronavirus pandemic was described by Professor Whitworth, who provided expert evidence to the Inquiry about infectious disease surveillance, as a “reasonable bet” prior to 2020, with another being “very plausible” in the future.³⁸ |

| 1.15. | Furthermore, it was and is not difficult to contemplate a virus that is more transmissible and more lethal. Covid-19 had a case fatality ratio of between 0.5 and 1%.³⁹ By comparison, the case fatality ratios of SARS and MERS at the beginning of the outbreaks (ie before population immunity or clinical countermeasures) were approximately 10% and 35% respectively.⁴⁰ Professor Mark Woolhouse, Professor of Infectious Disease Epidemiology at the University of Edinburgh, underscored this:

“[O]n the scale of potential pandemics, Covid-19 was not at the top and it was possibly quite far from the top. It may be that next time – and there will be a next time … we are dealing with a virus that is much more deadly and is also much more transmissible … The next pandemic could be far more difficult to handle than Covid-19 was, and we all saw the damage that that pandemic caused us.”⁴¹ |

| 1.16. | In the light of that history, the UK’s resilience to and its preparedness for pandemics are matters of vital importance to the security of the nation. However, it is crucial even following the recent experience of the Covid-19 pandemic not to lose perspective, either on the risk or on what can be done about it. As Professor Whitworth and Dr Hammer told the Inquiry:

“The COVID-19 epidemic was unprecedented in recent times, and it would not be reasonable to expect the UK to be fully prepared for a hypothetical epidemic of this size of a previously unknown pathogen.”⁴² |

| 1.17. | The Inquiry agrees. Even the threat of an outbreak has a significant impact on society’s preparedness – whether an epidemic occurs or not. The potential disruption to social and economic life, and the cost (in real financial terms and opportunity) as the result of a false alarm, may be disproportionate to the burden of an actual epidemic or pandemic. There are proper limits to preparedness and resilience (as there are for security), but improvements, even radical ones, can still be made. It is critical for any government, with the public’s approval, to steer a course between complacency and overreaction.⁴³ |

- Charlotte Hammer 14 June 2023 81/4-12

- Charlotte Hammer 14 June 2023 81/4-12; INQ000196611_0005 para 3. The UK government considers that infectious disease outbreaks are likely to be more frequent up to 2030 and another novel pandemic remains a realistic possibility; see: Global Britain in a Competitive Age, HM Government, March 2021, p31 (https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/60644e4bd3bf7f0c91eababdGlobal_Britain_in_a_Competitive_Age_the_Integrated_Review_of_Security__Defence__Development_and_Foreign_Policy.pdf; INQ000196501).

- INQ000207453

- INQ000207453. For up-to-date figures, see Deaths Registered Weekly in England and Wales, Provisional, Office for National Statistics, 2024 (https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/datasets/weeklyprovisionalfiguresondeathsregisteredinenglandandwales).

- INQ000184638_0008 para 1.12

- INQ000196611_0007-0008 paras 8, 13

- INQ000196611_0008-0009 paras 13-15

- INQ000184638_0041 para 5.19

- INQ000184638_0041 para 5.21

- See Table 1 above; INQ000207453_0001; INQ000196611_0007 para 10

- INQ000184638_041 para 5.21

- Christopher Whitty 22 June 2023 93/15-22

- INQ000184638_0043 para 5.28; Richard Horton 13 July 2023 67/15-19

- Richard Horton 13 July 2023 67/15-68/13

- INQ000195846_0007 para 21

- ‘Lessons learned from SARS: The experience of the Health Protection Agency, England’, N.L. Goddard, V.C. Delpech, J.M. Watson, M. Regan and A. Nicoll, Public Health (2006), 120, 27-32 (http://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2005.10.003; INQ000187893-1)

- INQ000195846_0010 paras 36-37

- INQ000195846_0011 para 40

- Sustaining Global Surveillance and Response to Emerging Zoonotic Diseases, Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2009, p44 (https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/12625/chapter/1; INQ000149100); INQ000196611_0006, 0016 paras 7, 33

- INQ000195846_0006 para 16. For example, the original hosts of influenza pandemics are usually wild aquatic birds, with intermediary hosts found among wild birds, livestock and mammals such as pigs (INQ000196611_0007 para 9). The original hosts of coronaviruses are most likely bats, with intermediary hosts in previous outbreaks having been other mammals such as civets, as in SARS, and dromedary camels, as in MERS (INQ000196611_0008 para 11). Close contact may involve consumption, hunting, live animal wet markets, handling or cohabitation (INQ000196611_0006 para 7).

- INQ000196611_0016 para 33. As at June 2024, the World Health Organization’s priority diseases and pathogens include Covid-19, Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever, Ebola virus disease and Marburg virus disease, Lassa fever, MERS, SARS, Nipah and henipaviral diseases, Rift Valley fever, Zika virus and ‘Disease X’ (INQ000196611_0008, 0017 paras 13-15, 35).

- INQ000196611_0006 para 6

- INQ000196611_0005-0006, 0006-0007 paras 5, 7

- Charlotte Hammer 14 June 2023 81/22-85/2; INQ000196611_0006 para 7

- INQ000196611_0005 para 3

- INQ000196611_0005-0006 para 5

- INQ000196611_0010-0011 para 19

- INQ000196611_0005-0006 para 5

- INQ000196611_0007 para 8

- INQ000196611_0010 paras 18-21

- INQ000184638_0037-0038, 0040-0041, 0042 paras 5.4, 5.16-5.21, 5.23

- INQ000184638_0037-0038 para 5.4

- See Table 1 above; INQ000207453

- See Table 1 above; INQ000207453; INQ000184638_0038 para 5.5

- These four outbreaks were SARS (2002 to 2003), MERS in Saudi Arabia (2012 onwards), MERS in South Korea (2015) and Ebola (2013–2016).

- Mark Woolhouse 5 July 2023 115/7-117/1; see also INQ000149116_0002

- Sustaining Global Surveillance and Response to Emerging Zoonotic Diseases, Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2009, pp1-4 (https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/12625/chapter/1; INQ000149100); Charlotte Hammer 14 June 2023 81/22-82/22; Preparedness for a High-Impact Respiratory Pathogen Pandemic, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, September 2019, pp19-20 (https://www.gpmb.org/reports/m/item/preparedness-for-a-high-impact-respiratory-pathogen-pandemic; INQ000198916)

- Jimmy Whitworth 14 June 2023 104/3-10

- INQ000195846_0008 para 25

- INQ000195846_0008 para 25

- Mark Woolhouse 5 July 2023 148/5-22

- INQ000196611_0034 para 86

- INQ000196611_0011-0012 para 22

Chapter 2: The system — institutions, structures and leadership

Introduction

| 2.1. | In the UK (including in the devolved nations: Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland), there are a multitude of institutions, structures and systems responsible for pandemic preparedness, resilience and response. |

| 2.2. | The Inquiry set out the principal bodies and the ways in which they were linked in a series of organograms, referred to in the course of the Module 1 hearings as the ‘spaghetti diagrams’. These show a complex system that had grown over many decades, ostensibly to provide the UK government and devolved administrations with a coherent and effective approach to preparing for a pandemic.¹ |

| 2.3. | This chapter examines the key institutions, structures and systems. An effective emergency preparedness and resilience system ought to have been the shared endeavour of the UK government and devolved administrations. The system ought to have been simple, clear and purposeful. It should have been organised in a rational and coherent form to ensure that the UK government and devolved administrations were prepared for a pandemic. This chapter also considers the effectiveness of the lead government department model in the UK for building preparedness for and resilience to whole-system civil emergencies. |

The international system of biosecurity

| 2.4. | The principal aim of biosecurity (an umbrella term for the preparation, policies and actions to protect human, animal and environmental health against biological threats) is the protection of society from the harmful effects of infectious disease outbreaks.² There is a balance to be struck between overreaction and being excessively cautious. A small cluster of infections may or may not become established in the population. In the early stages of an outbreak, therefore, the likely public health burden is quite unpredictable – it could range from the trivial to the devastating.³ Furthermore, when there is greater surveillance for emerging infections, there will naturally be more “‘false alarms’”.⁴ Thus, surveillance itself carries the risk of ‘crying wolf’. A society that is unduly frightened is not a resilient one. If the alarm is sounded without due cause, cynicism about the risks posed by more serious outbreaks will undermine society’s trust in biosecurity.⁵ |

| 2.5. | Critical to an effective alert system are transparency and the flow of information, both within the UK and internationally. The international system of biosecurity is based on cooperation between nations through organisations and frameworks, including:

|

| 2.6. | At present, there is little or no incentive – and much disincentive – for countries to report outbreaks of disease within their borders. The ramifications for doing so include potential economic damage and a certain level of stigma. Recent examples that demonstrate hesitancy to report outbreaks are instructive. They include Saudi Arabia’s disclosure of the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreak and the Chinese government’s disclosure of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).⁹ |

| 2.7. | The global landscape of surveillance coordination for infectious diseases is currently in flux as changes are being made at several levels, including the UK’s exit from the EU, negotiations about a pandemic treaty that may replace the current regulations and the creation in September 2021 of the European Commission’s Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Authority. It is too early to assess the impact of these changes.¹⁰ |

| 2.8. | While a certain level of realism is required, the culture among the international community should develop into one of candour between nations and openness with the public about the reporting of novel pathogen outbreaks. The UK government could contribute towards building such a culture by engaging further with the work of global institutions, such as the World Health Organization, and the many regional and international systems of surveillance and response. The more information that can be obtained and shared, and the more intelligently it can be interrogated, the more prepared the UK and other countries will be. |

The United Kingdom

| 2.9. | Much attention is directed in government literature to the issue of ‘whole-system’ civil emergencies. These are events or situations that threaten serious damage to human welfare, the environment or the security of the UK.¹¹ They are generally categorised either as a hazard (a risk with a non-malicious cause) or a threat (a risk that does have a malicious cause).¹² |

| 2.10. | Whether or not a civil emergency is a whole-system civil emergency is principally a question of scale. Civil emergencies on a small scale impact fewer people and involve fewer decision-makers in preparedness, resilience and response. For example, a rail accident is principally a transport-related issue and flooding is largely an environmental issue. Consequently, preparedness, resilience and response are led at a national level by relevant specialist departments – the Department for Transport and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, or their equivalent directorates or departments in the devolved administrations.¹³ These are more “normal” civil emergencies.¹⁴ |

| 2.11. | Other civil emergencies have much broader and deeper impacts and require significantly more decision-makers for all aspects of preparedness, resilience and response. The most complex civil emergencies engage the whole system of central, regional and local government across the UK and the whole of society.¹⁵ Whole- system civil emergencies impact on the whole society of the UK and require a cross- departmental approach within, as well as between, the UK government and devolved administrations. |

| 2.12. | There is, at present, no agreed definition between the UK government and devolved administrations about what amounts to a whole-system civil emergency. This should be rectified. A single definition, based on the above, should be created and used to determine the structures needed in the response, the assessment of risk and the design of strategy. One thing is clear, however: a pandemic that kills human beings is a whole-system civil emergency. The risk of a pandemic therefore demands careful assessment, planning and response. |

| 2.13. | The UK is itself complex and has distinct legal systems and varied devolution frameworks that devolve power differently to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Although there are differences in each devolution settlement, health has been a primarily devolved matter in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland since 1999. |

| 2.14. | However, the Civil Contingencies Act 2004 and associated regulations and guidance set out the framework for civil protection in an emergency across the UK, taking into account the devolution of powers.¹⁶ The Act divides local responders – representatives from public services including the emergency services, local authorities, the NHS and the Health and Safety Executive – into two categories, imposing a different set of duties on each. It is supported by statutory guidance, Emergency Preparedness, and a suite of non-statutory guidance, including Emergency Response and Recovery.¹⁷ At the time of the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic, the legislative framework and associated national guidance was “widely acknowledged [by public health specialists and practitioners] as being outdated and did not relate to contemporary structures, roles and responsibilities”.¹⁸ As is being examined in subsequent modules of the Inquiry, it was not utilised. |

| 2.15. | There should be cooperation between the UK government and devolved administrations at all levels. The best defence against the spread of pathogens was and remains strong national surveillance and detection mechanisms – as all international systems are ultimately built upon these – and effective collaboration between the various levels of responsibility.¹⁹ |

| 2.16. | Within the UK, surveillance involves the ongoing, systematic collection, collation, analysis and interpretation of data, with dissemination of information to those that need it (including those at the local level); this is primarily undertaken by the UK Health Security Agency.²⁰ Dr Charlotte Hammer, expert witness on infectious disease surveillance (see Appendix 1: The background to this module and the Inquiry’s methodology), noted the importance of an early alert:

“The earlier your alert, the more likely you can actually respond to it, because the response will be much, much smaller, and a much smaller response can be mounted more often.”²¹ |

The UK government and supporting organisations in England

Figure 1: Pandemic preparedness and response central government structures in the UK and England – c. August 2019

Source: Extract from INQ000204014

Figure 2: Pandemic preparedness and response structures in the UK and England – c. August 2019

Source: Extract from INQ000204014

The Cabinet Office

| 2.17. | The Cabinet Office is the UK government department responsible for supporting the Prime Minister, the Cabinet and the functioning of government more broadly. |

| 2.18. | The Civil Contingencies Secretariat sat within the National Security Secretariat of the Cabinet Office.²² It had a number of roles, including:

|

| 2.19. | Katharine Hammond, Director of the Civil Contingencies Secretariat from August 2016 to August 2020, told the Inquiry that it was principally a “co-ordinating” body for whole-system civil emergency planning, response and recovery.²⁶ Although it was located at the centre of government, it did not lead and was not in charge of the preparedness and resilience of other government departments. Each government department was in charge of managing the risks that fell within its remit.²⁷ |

| 2.20. | There was a historical problem at the centre of government: a difference between the amount of time and resources dedicated to considering threats and hazards. Ms Hammond suggested that this reflected the view that malicious threats could, by their nature, seem more alarming and were more likely to be preventable.²⁸ During her tenure as Director of the Civil Contingencies Secretariat, part of Ms Hammond’s role was to ensure that non-malicious risks – known as hazards as opposed to threats – received adequate attention and focus from all government departments.²⁹ |

Ministerial oversight

| 2.21. | David Cameron MP, Prime Minister from May 2010 to July 2016, made it one of the aims of his government to make the architecture of dealing with civil contingencies and national security “more strategic”.³⁰ The purpose was to enable the UK government to take a longer-term view of the risks on the horizon regarding the UK’s security.³¹ One of Mr Cameron’s first acts in government was to establish a National Security Council as a Cabinet Committee, supported by a National Security Secretariat and a National Security Adviser.³² The National Security Council was the main forum for ministerial discussion of the UK government’s objectives for national security, including resilience.³³ It focused on malicious threats.³⁴ |

| 2.22. | In addition, the National Security Council (Threats, Hazards, Resilience and Contingencies) sub-Committee was created with a focus on emergency planning and preparedness, which included non-malicious hazards.³⁵ Sir Oliver Letwin MP, Minister for Government Policy from May 2010 to July 2016 and Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster from July 2014 to July 2016, was placed in charge of the Threats, Hazards, Resilience and Contingencies sub-Committee and would chair it in Mr Cameron’s absence. He was described as “in many ways, the Resilience Minister”.³⁶ Mr Cameron told the Inquiry that having a strong Cabinet minister with “the ear of the Prime Minister” in this position was the right approach because only the Prime Minister is in the position to put the full weight of government behind their decisions.³⁷ |

| 2.23. | The Threats, Hazards, Resilience and Contingencies sub-Committee provided the Prime Minister with an overview of the potential civil domestic disruptive challenges that the UK might face over the next 6 months (as distinct from the National Risk Register’s 5-year timeframe and the National Security Risk Assessment’s 20-year timeline).³⁸ In 2016, following the outbreak of Ebola virus disease in 2013, the UK government established a specialist horizon-scanning unit for viruses that might affect the UK, which fed into the Threats, Hazards, Resilience and Contingencies sub-Committee.³⁹ |

| 2.24. | The Threats, Hazards, Resilience and Contingencies sub-Committee was important to the implementation of the UK Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Strategy 2011 (the 2011 Strategy):

“comprising Ministers from across Central Government departments and the [devolved administrations], oversees and coordinates national preparations for all key UK risks including pandemic influenza”.⁴⁰ The sub-Committee put the weight of the Cabinet and the Prime Minister behind important activities of preparedness. The Inquiry was told by Mr Cameron and Sir Oliver Letwin that this was necessary to ensure that important issues were acted upon.⁴¹ |

| 2.25. | The last occasion on which the Threats, Hazards, Resilience and Contingencies sub-Committee met was in February 2017 (see Chapter 5: Learning from experience).⁴² In July 2019, the sub-Committee was formally “taken out of the committee structure”.⁴³ Ms Hammond suggested that it could be “reconvened if needed” but accepted that it was, in effect, abolished.⁴⁴ As a result, immediately prior to the pandemic, there was no cross-government ministerial oversight of the matters that were previously within the sub-Committee’s remit. |

The Department of Health and Social Care⁴⁵

| 2.26. | Most emergencies in the UK are handled locally by emergency services. However, where the emergency’s scale or complexity is such that it requires UK government coordination or support, a designated lead government department is responsible for the overall management of the planning and response.⁴⁶ The Department of Health and Social Care was the UK government’s lead government department responsible for pandemic preparedness, response and recovery.⁴⁷ |

| 2.27. | In 2007, the Department of Health established the Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Programme.⁴⁸ This programme was focused on the management of pandemic influenza preparedness within the health and social care system in England. Its board comprised officials from the Department of Health, the Cabinet Office, NHS England and Public Health England.⁴⁹ As discussed later in this Report, the UK government’s assessment of pandemic risk and its strategies for dealing with that risk both suffered because they focused almost entirely on influenza as the most likely cause of a pandemic. The Covid-19 pandemic was, of course, caused by a coronavirus. |

| 2.28. | There was also the Pandemic Flu Readiness Board, which was established in March 2017 by the Threats, Hazards, Resilience and Contingencies sub-Committee.⁵⁰ It was intended to coordinate planning across the UK by involving the devolved administrations and 14 relevant UK government departments.⁵¹ From February 2018, the Pandemic Flu Readiness Board was co-chaired by Ms Hammond, on behalf of the Cabinet Office, and Emma Reed, Director of Emergency Preparedness and Health Protection in the Department of Health and Social Care.⁵² Again, this board was concerned only with preparing for an influenza pandemic. Moreover, its work overlapped with the work of the Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Programme. |

| 2.29. | In 2021, apparently in acknowledgement of its fundamental structural flaws, the Pandemic Flu Readiness Board was replaced by an entity called the Pandemic Diseases Capabilities Board. This would consider preparedness for a broad range of pandemics, including but not limited to pandemic influenza, and would focus on the practical capabilities needed to respond to pandemics.⁵³ |

Public Health England

| 2.30. | Before the Covid-19 pandemic, the principal responsibility for managing high consequence infectious disease outbreaks lay with Public Health England. This body was established in 2013 as an executive agency of the Department of Health, to protect and improve health and wellbeing and reduce health inequalities. It primarily covered England, with limited UK-wide responsibilities.⁵⁴ |

| 2.31. | Public Health England’s functions for pandemic preparedness and resilience included:

|

| 2.32. | Duncan Selbie, Chief Executive of Public Health England from July 2012 to August 2020, described it as:

“well prepared for the emergency health protection work that it was commissioned by [the Department of Health and Social Care] to perform … but … not fully prepared to deal with the scale and magnitude of the pandemic of unknown origin that the world faced in January 2020”.⁶⁰ |

| 2.33. | In the event, Public Health England was effectively abolished by the UK government following the commencement of the pandemic. From 2021, the UK Health Security Agency brought together the staff and capabilities of NHS Test and Trace and the health protection elements of Public Health England.⁶¹ Sir Christopher Wormald, Permanent Secretary to the Department of Health and Social Care from May 2016, described the UK Health Security Agency as providing “permanent standing capacity to prepare for, prevent and respond to threats to health”.⁶² Its creation to fulfil this purpose demonstrated that there was no such effective permanent standing capacity prior to the pandemic. |

Expert medical and scientific advice

| 2.34. | The Chief Medical Officer for England is a doctor, public health leader and public official, as well as the Chief Medical Adviser to the UK government. The Office of the Chief Medical Officer comprises fewer than 20 people, including the Chief Medical Officer and Deputy Chief Medical Officers.⁶³ The Chief Medical Officer’s responsibilities fall broadly into three areas: providing independent scientific advice to ministers across the UK government on medical and public health issues; communicating to the public on health matters in times of emergency; and serving as part of the collective leadership of the medical and public health professions.⁶⁴ The combined roles of Chief Medical Officer for England and Chief Medical Adviser to the UK government run parallel to the system of chief scientific advisers. |

| 2.35. | The system for providing scientific advice to decision-makers spanned the whole UK government. Each department and its supporting organisations had their own method by which scientific information, advice and analysis were provided to decision-makers.⁶⁵ The UK government was also advised by a large number of scientific advisory groups, committees and entities relevant to human infectious diseases and pandemic preparedness. These groups were largely, but not exclusively, sponsored by the Department of Health and Social Care as the lead government department for human infectious disease risks. They generally reported their advice directly to its officials. |

| 2.36. | Each of these groups had a separate remit and specialisation. The key scientific advisory groups relevant to human infectious disease risks were:

|

| 2.37. | Most UK government departments also had a departmental chief scientific adviser.⁷⁵ They were responsible for ensuring mechanisms were in place to provide advice to policy-makers and ministers, both within their departments and across the UK government.⁷⁶ The system of departmental chief scientific advisers was one of the key means of bridging the gap between the decentralisation of scientific advice in each UK government department and embedding a coherent and consistent scientific advice system across the UK government as a whole.⁷⁷ |

| 2.38. | At the centre of the UK government scientific advice system was the Government Chief Scientific Adviser supported by the Government Office for Science (also known as GO-Science).⁷⁸ They were responsible for providing scientific advice to the Prime Minister and members of the Cabinet, advising the UK government on aspects of science for policy (as opposed to science policy itself) and improving the quality and use of scientific evidence and advice in government.⁷⁹ One of the main forums for the sharing of information was the Chief Scientific Adviser Network, which consisted of the Government Chief Scientific Adviser and departmental chief scientific advisers and which usually met on a weekly basis.⁸⁰ |

| 2.39. | The UK government’s expert medical and scientific advice system had two main strengths. Firstly, relatively few emergencies involved only a single department and the network across government allowed for the rapid transmission of technical information to the departments that needed it.⁸¹ Secondly, each scientific adviser could call on the specialist capabilities from within their own department.⁸² Professor Sir Christopher Whitty, Chief Medical Officer for England from October 2019, told the Inquiry that the “UK science advisory system is complex and not perfect but is considered to be one of the stronger ones internationally”.⁸³ Sir Jeremy Farrar, Chief Scientist at the World Health Organization from May 2023 and Director of the Wellcome Trust from 2013 to 2023, agreed.⁸⁴ |

Coordinating regional and local activities in England and Wales

| 2.40. | Local resilience forums are the principal mechanism in England and in Wales for emergency preparedness and cooperation between agencies. Their main purpose is to ensure that local responders are able effectively to act on the duties imposed upon them under the Civil Contingencies Act 2004.⁸⁵ |

| 2.41. | The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Governments (through its Resilience and Emergencies Division, now renamed the Resilience and Recovery Directorate) shared responsibility for local resilience in England with the Cabinet Office.⁸⁶ The role of the Resilience and Emergencies Division (through teams of resilience advisers) was principally to help responders identify for themselves the risks they faced and how to mitigate those risks, and to manage the impact of risks that materialised. It would act akin to a ‘critical friend’, question rationales, suggest alternatives, share good practice and support local planning activities. It contributed, advised, facilitated and participated.⁸⁷ However, it was not the role of the Resilience and Emergencies Division to provide leadership and it did not ensure that local responders fulfilled their statutory duties.⁸⁸ |

| 2.42. | Mark Lloyd, Chief Executive of the Local Government Association from November 2015, described the link between the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government and local resilience forums as “strong”.⁸⁹ However, in other respects, he described a “fragmentation” because, while the Cabinet Office coordinated activity on national incidents, the Department of Health and Social Care had specific responsibility for pandemics. Mr Lloyd said that, as a result, officials in the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government had a “big challenge” in managing the interface between central and local government.⁹⁰ Important links between local and national governments were missing. |

| 2.43. | When national guidance was developed under the Civil Contingencies Act 2004, there was also a lack of understanding at the UK government level about the inter-relationships between entities at the local level.⁹¹ |

| 2.44. | Local structures are not aligned. For example, local resilience forums are geographically defined by police force areas, but local health resilience partnerships (strategic forums for organisations in the local health sector) follow the geographical boundaries of the integrated care system. This means that the geographical areas covered by directors of public health do not always match those of local resilience forums or local health resilience partnerships.⁹² This structural flaw, for which the Cabinet Office was ultimately responsible, is potentially a recipe for confusion and duplication. Professor Jim McManus, President of the Association of the Directors of Public Health from October 2021 to October 2023, told the Inquiry that this could be “tidied up”.⁹³ |

| 2.45. | Another key issue was that, while directors of public health (specialists accountable for the delivery of their local authority’s public health duties) co-chaired local health resilience partnerships, they did not routinely sit on local resilience forums because they were not invited to do so.⁹⁴ Structurally, this created a gap when it came to addressing a public health emergency, with professionals in civil contingencies and public health not appropriately connected. The directors of public health, the public health workforce and local government have a critical contribution to make to pandemic preparedness and resilience. Their knowledge and skills are an important local and national resource to be drawn upon in whole-system civil emergency preparedness and resilience.⁹⁵ They are in regular contact with the local population and therefore have an important role in communicating their needs to the institutions whose responsibility it is to prepare for and build resilience to whole-system civil emergencies.⁹⁶ There should be far greater involvement of directors of public health and local public health teams in developing those plans. |

| 2.46. | Dr Claas Kirchhelle, expert witness to the Inquiry on public health structures (see Appendix 1: The background to this module and the Inquiry’s methodology), described a lengthy cycle of centralisation and fragmentation resulting in a “misalignment” in the UK’s health, social care and pandemic preparedness structures and systems.⁹⁷ The issues of constant reorganisation and rebranding go to the top of the institutions responsible for preparedness and resilience in the UK. For example, in September 2022, the Civil Contingencies Secretariat was subject to a split into a Resilience Directorate and a separate COBR Unit. This was apparently to give effect to a change in “purpose” and “focus” and a “slightly different framing”.⁹⁸ However, the headcount remained very similar and there did not appear to be a substantive difference between the old system and the new.⁹⁹ |

Scotland

Scottish Government and supporting organisations

Figure 3: Pandemic preparedness and response central government structures in Scotland – c. 2019

Source: Extract from INQ000204014

Figure 4: Pandemic preparedness and response structures in Scotland – c. 2019

Source: Extract from INQ000204014_0006

| 2.47. | John Swinney MSP was the Deputy First Minister in the Scottish Government from November 2014 to March 2023. As Deputy First Minister, Mr Swinney held ministerial responsibility for resilience. Those responsibilities are now held by the Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Home Affairs.¹⁰⁰ Mr Swinney described his position as “participating in, and ultimately leading, the Resilience function of the Scottish Government”.¹⁰¹ |

| 2.48. | In Scotland, the Cabinet Sub-Committee Scottish Government Resilience provided ministerial oversight to strategic policy and guidance in the context of resilience in Scotland.¹⁰² Its last meeting took place in April 2010, when, according to the minutes, it had a full programme of work.¹⁰³ This work was taken up by the Scottish Resilience Partnership, which had direct ministerial involvement in order to provide “strategic ministerial direction”.¹⁰⁴ As those attending were all members of the Cabinet, if necessary, issues could be taken up in that forum.¹⁰⁵ Gillian Russell, Director of Safer Communities from June 2015 to March 2020, said that, in her experience, the Scottish Cabinet took decisions on resilience rather than working through a sub-committee.¹⁰⁶ Nonetheless, Mr Swinney told the Inquiry:

“[T]here may well be the need for a particular forum to look periodically, formally, in a recorded fashion, to take stock about where preparations happen to be.”¹⁰⁷ |

| 2.49. | Resilience was centralised in the Scottish Government around a ‘hub and spokes’ model. At the centre of the model – the hub – was Preparing Scotland.¹⁰⁸ This was a set of national guidance documents for civil emergencies, which set out:

“how Scotland is prepared. It identifies structures, and assists in planning, responding and recovering from emergencies. It is not intended to be an operations manual. Rather, it is guidance to responders to assist them to assess, plan, respond and recover.”¹⁰⁹ |

| 2.50. | The Resilience Division in the Scottish Government led on emergency planning, response and recovery, as well as on the strategy, guidance and work programme for improving the resilience of essential services in Scotland and the Preparing Scotland guidance.¹¹⁰ Its wide remit included overseeing the capability and capacity at national, regional and local levels to prepare for and respond to civil emergencies, including pandemic influenza.¹¹¹ It was also responsible for the Scottish Government Resilience Room. This meant that the entity responsible for preparedness and resilience was integrated with the entity responsible for response.¹¹² |

| 2.51. | Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, the Resilience Division was relocated from a directorate in the Directorate-General Constitution and External Affairs to a directorate in the Directorate-General Education and Justice.¹¹³ Later, in April 2021, it was moved back to a directorate in the now renamed Directorate-General Strategy and External Affairs.¹¹⁴ The Inquiry notes that entities responsible for resilience are too often the subject of reorganisation in Scotland, as they are in the other devolved administrations and the UK government. However, there is some degree of continuity in that the Civil Service in Scotland does not have departments based on the Whitehall model, but instead has a more flexible and unified structure, comprising directorates and executive agencies.¹¹⁵ Mr Swinney also retained political leadership for resilience matters throughout all of the changes prior to his resignation as Deputy First Minister in March 2023.¹¹⁶ |

| 2.52. | Further from the centre of government, structures were more diffuse and, as a consequence, more confusing. The Scottish Government had its own Pandemic Flu Preparedness Board.¹¹⁷ Health Protection Scotland (which was part of NHS National Services Scotland but also had joint accountability to the Scottish Government and the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities) was responsible for providing national leadership to protect the Scottish public from infectious diseases and for preparing for outbreaks.¹¹⁸ There were also several public health divisions based within the Directorate of Population Health and the Emergency Preparedness Resilience and Response Division (within the Directorate of the Chief Operating Officer).¹¹⁹ On 1 April 2020, functions of Health Protection Scotland were transferred to a new body, Public Health Scotland, plans for which were rapidly revised for the Covid-19 pandemic.¹²⁰ |

Expert medical and scientific advice

| 2.53. | In Scotland, the Chief Medical Officer had only a limited role in pandemic preparedness and resilience.¹²¹ The Chief Scientific Adviser to the Scottish Government did not hold primary responsibility for advice on public health, public health-related science and epidemiology.¹²² The Chief Scientist (Health) in Scotland similarly did not have a role in pandemic preparedness.¹²³ Scotland substantially relied, in terms of expert medical and scientific advice, on “UK intelligence”.¹²⁴ |

Coordinating regional and local activities

| 2.54. | Coordination between emergency responders was undertaken by three Regional Resilience Partnerships, composed of representatives from Category 1 and Category 2 responders and others as deemed necessary.¹²⁵ Within each Regional Resilience Partnership area are several Local Resilience Partnerships.¹²⁶ The regional and local partnerships covered both preparedness and response.¹²⁷ The Scottish Government coordinated with those partnerships through embedded teams of coordinators.¹²⁸ |

| 2.55. | The Scottish Resilience Partnership also brought together a core group of Scottish Government officials, Category 1 responders and representatives from the Society of Local Authority Chief Executives, as well as Scotland’s 12 Local Resilience Partnerships. It would meet “on a periodic basis to supervise the preparation for resilience activity”.¹²⁹ Mr Swinney said that ministers also attended “quite frequently” to “provide the direction of ministerial thinking”.¹³⁰ |

Wales

Welsh Government and supporting organisations

Figure 5: Pandemic preparedness and response central government structures in Wales – c. 2019

Source: Extract from INQ000204014

Figure 6: Pandemic preparedness and response structures in Wales – c. 2019

Source: Extract from INQ000204014

| 2.56. | The First Minister had overall responsibility for civil contingencies and resilience within the Welsh Government.¹³¹ This gave significant recognition to its importance. There existed beneath the First Minister a very complicated array of committees, teams, groups and sub-groups, which indicates that the Welsh Government was not as “compact” an administration as suggested to the Inquiry by Dr Andrew Goodall, Permanent Secretary to the Welsh Government from September 2021.¹³² |

| 2.57. | There were multiple entities involved in preparedness and resilience, split across several bodies.¹³³ They included:

|