Executive summary

Hindi kinakatawan ng ulat na ito ang mga pananaw ng Imbestigasyon. Ang impormasyon ay sumasalamin sa buod ng mga karanasang ibinahagi sa amin ng mga dumalo sa aming mga Roundtable noong 2025. Ang hanay ng mga karanasang ibinahagi sa amin ay nakatulong sa amin na bumuo ng mga temang aming susuriin sa ibaba. Makikita mo ang listahan ng mga organisasyong dumalo sa roundtable sa annex ng ulat na ito.

Ang ulat na ito ay naglalaman ng mga paglalarawan ng mga epekto sa kamatayan, pagpapakamatay, at kalusugang pangkaisipan. Maaaring nakababahala ang mga ito sa ilan. Hinihikayat ang mga mambabasa na humingi ng suporta kung kinakailangan. Ang isang listahan ng mga serbisyong sumusuporta ay ibinibigay sa website ng UK Covid-19 Inquiry.

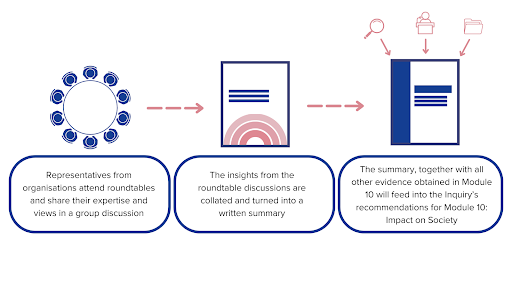

Noong Marso 2025, tinipon ng UK Covid-19 Inquiry ang mga kinatawan ng mga organisasyon mula sa iba't ibang sektor ng mga pangunahing manggagawa para sa isang roundtable discussion upang tuklasin ang epekto ng pandemya sa mga pangunahing manggagawa, kabilang ang epekto ng mga hakbang na ipinatupad upang tumugon sa pandemya. Hindi kasama rito ang mga manggagawang pangkalusugan at mga manggagawa sa pangangalagang panlipunan, dahil ang epekto sa mga grupong ito ang naging pokus ng Modyul 3 at Modyul 6 ng Pagtatanong.

Binubuod ng ulat na ito ang mga temang itinaas sa mga talakayan kasama ang mga kinatawan sa larangan ng edukasyon, bumbero at pagsagip, libing, libing at kremasyon.1, pulisya at hustisya, mga sektor ng tingian, transportasyon, pamamahagi at pagbobodega.

Ang pandemya ay nagkaroon ng malaking epekto sa mga pangunahing manggagawa sa lahat ng sektor. Kabilang dito ang mga epekto ng pag-unawa at pagpapatupad ng mga paghihigpit ng gobyerno at pamamahala sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho, at ang takot na mahawa ng Covid-19. Ang takot ay laganap sa mga pangunahing manggagawa na nag-aalala para sa kanilang sariling kaligtasan at para sa kanilang mga pamilya, lalo na kung sila ay nakikipag-ugnayan sa mga taong may klinikal na kahinaan.

Ang kakulangan ng mga planong partikular sa sektor para sa pagtugon sa pandemya ay humantong sa kalituhan, kawalan ng katiyakan, at takot sa mga pangunahing manggagawa. Lalo pa itong pinalala ng mga gabay na inilalabas nang gabi o tuwing Sabado at Linggo, lalo na sa mga unang yugto ng pandemya. Tinalakay ng mga kinatawan kung paano kinailangang bigyang-kahulugan ng mga unyon at lugar ng trabaho ang malawak na gabay nang nakapag-iisa, na kung minsan ay nagreresulta sa hindi pare-parehong mga kasanayan. Ang mga pagbabago sa gabay ng gobyerno at magkasalungat na gabay ay itinampok bilang mga pangunahing isyu at nag-iwan sa mga manggagawa na hindi sigurado sa kung ano ang dapat nilang gawin. Nahirapan din silang ipatupad ang mga itinuturing na hindi praktikal na paghihigpit sa mga gusaling masikip o kulang sa wastong bentilasyon. Nangangahulugan ito na ang mga unyon at mga katawan ng kalakalan ay kailangang gumanap ng mas malaking papel sa pagbuo at pagbabahagi ng kanilang sariling gabay upang suportahan ang mga sektor at ang kanilang mga manggagawa.

Nagdulot din ng mga pagbabago sa mga paraan ng pagtatrabaho ang pandemya. Ang ilang mga manggagawa ay nakapagtrabaho nang malayuan habang ang iba ay kinakailangang patuloy na magtrabaho nang personal at makipag-ugnayan sa mga kasamahan at sa publiko. Sinasabing lumikha ito ng mga tensyon at nagbigay-diin sa hierarchical na katangian ng ilang mga lugar ng trabaho, na nagparamdam sa mga manggagawa na hindi gaanong pinahahalagahan.

Para sa ilang mahahalagang manggagawa, bumuti ang moral sa simula dahil ang mahalagang katangian ng kanilang tungkulin ay kinilala sa isang bagong paraan. Gayunpaman, habang tumatagal ang pandemya, bumaba ang moral sa iba't ibang sektor, lalo na nang magkasakit o namatay ang mga kasamahan dahil sa Covid-19. Bumaba rin ang moral dahil sa patuloy na pagkaramdam ng stress ng mga pangunahing manggagawa at habang tumatagal, minamaliit ang pagpapahalaga.

Ang gabay sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho ay inilarawan bilang hindi pare-pareho at hindi malinaw, na humantong sa pakiramdam ng mga pangunahing manggagawa na nasa panganib na mahawaan ng Covid-19. Nabanggit ng mga kinatawan na nang ipakilala ang mga hakbang, hindi malinaw kung aling mga hakbang ang pinakamahalaga. Kapag hindi sinunod ang mga hakbang sa lugar ng trabaho, hindi malinaw kung paano dapat iulat ang mga paglabag o kung sino ang dapat managot. Gayunpaman, isinaalang-alang ng mga kinatawan na sa ilang sektor, bumuti ang mga hakbang sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho habang nagpapatuloy ang pandemya.

Ang mga nagtatrabaho sa mga pampublikong trabaho noong panahon ng pandemya ay inilarawan bilang ang may pinakamalaking panganib na mahawa ng Covid-19. Ang mga manggagawang ito ay sinasabing hindi proporsyonal na nagmula sa mga etnikong minorya at/o kababaihan. Ang panganib na mahawa ng Covid-19 ay itinuring na isang partikular na pag-aalala para sa mga taong nagmula sa mga etnikong minorya na nakaranas ng mas mahinang resulta sa kalusugan dahil sa Covid-19. Itinampok din ng mga kinatawan kung paano naharap sa publiko ang pisikal at berbal na pang-aabuso mula sa publiko dahil sa pagpapatupad ng pagsusuot ng maskara at iba pang mga paghihigpit sa mga lugar tulad ng tingian, transportasyon at sa mga libing, libing, kremasyon at iba pang mga seremonya sa pagtatapos ng buhay.

Noong panahon ng pandemya, ang mga pangunahing manggagawa ay nakaranas ng karagdagang mga pressure sa trabaho bukod pa sa stress ng buhay sa labas ng trabaho dulot ng pandemya, kadalasan ay kakaunti o walang access sa suporta sa kalusugang pangkaisipan at kagalingan. Nadama ng mga kinatawan na ang kawalan ng komprehensibong mga serbisyo sa kalusugang pangkaisipan ay nagpalala sa mga damdamin ng pag-iisa, pagkabalisa, at burnout sa mga pangunahing manggagawa.

Ang mga presyur na kinakaharap ng mga pangunahing manggagawa ay kadalasang tumitindi dahil sa kakulangan ng mga tauhan. Sinabi ng mga kinatawan na ang mga sektor na nahaharap sa kakulangan ng mga tauhan ay minsan ay nagbibigay ng presyur sa kanilang mga pangunahing manggagawa na huwag mag-self-isolate o protektahan mula sa Covid-19 at pumasok sa trabaho. Nanganganib ito na lumala ang kanilang sariling kalusugan at ang kalusugan ng mga nasa kanilang sambahayan.

Ang pandemya ay nagkaroon ng malaking epekto sa pananalapi sa maraming pangunahing manggagawa, lalo na sa mga may kontratang zero-hours o nagtatrabaho para sa mga subcontractor. Ang mga manggagawa ay partikular na madaling kapitan ng kawalan ng seguridad sa pananalapi kapag nahaharap sa pinababang oras ng trabaho o hinihiling na mag-self-isolate nang walang sick pay.

Tinukoy ng mga kinatawan ang mga pare-parehong aral na maaaring matutunan mula sa mga karanasan ng mga pangunahing manggagawa sa lahat ng sektor upang mabawasan ang epekto sa anumang pandemya sa hinaharap. Nadama nila na kailangan ang mas madiskarteng pagpaplano at paghahanda para sa isang pandemya sa hinaharap na iniayon sa mga partikular na sektor, upang matiyak ang mabilis at organisadong tugon. Ang gabay sa pandemya sa hinaharap ay dapat na malinaw, pare-pareho, at napapanahon. Mas makakatulong ito sa mga pangunahing manggagawa na maipatupad ito nang epektibo.

Ang ilang mga puntong nabanggit sa mga roundtable ay naaangkop sa iba't ibang sektor, habang ang iba ay partikular sa sektor. Nilinaw namin ang mga puntong partikular sa sektor, sa pamamagitan ng paggamit ng mga heading na may kulay upang ipahiwatig kung kailan naaangkop ang isang punto sa isang sektor:

Mga Sektor

- Edukasyon

- Sunog at Pagsagip

- Mga Libing, Paglilibing at Kremasyon

- Pulisya at Hustisya

- Transportasyon, Pamamahagi at Pag-iimbak

- Pagtitingi

Binigyang-diin ng maraming kinatawan ang pangangailangan para sa higit na pagkilala at pagpapahalaga na ibigay sa mga pangunahing manggagawa sa isang pandemya sa hinaharap. Kabilang dito ang paglahok sa kanila sa paggawa ng desisyon sa pamamagitan ng kanilang mga unyon, pagpapabuti ng mga hakbang sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho at pagtiyak ng wastong pagkilala para sa kanilang mga kontribusyon, sa anyo ng suweldo at pasasalamat. Bagama't ang ilang sektor tulad ng transportasyon at bumbero at pagsagip ay nagtatag ng mga forum ng konsultasyon sa gobyerno sa simula pa lamang ng pandemya, na sa palagay nila ay humantong sa mas naaangkop na gabay para sa kanilang sektor, ang iba pang mga sektor tulad ng edukasyon at sektor ng pagtatapos ng buhay ay hindi nakinabang mula sa parehong pamamaraan ng konsultasyon. Nadama nila na humantong ito sa gabay na hindi praktikal para sa kanilang sektor. Binigyang-diin din ng mga organisasyon sa iba't ibang sektor ang pangangailangan para sa mas malaking pagtuon sa madaling makuhang suporta sa kalusugang pangkaisipan upang makatulong na mabawasan ang stress at maiwasan ang burnout.

- Ang karagdagang detalye tungkol sa pagdadalamhati at ang mga epekto ng mga paghihigpit sa mga libing ay makukuha sa ulat ng roundtable para sa mga libing, libing, at suporta sa pagdadalamhati [maaaring i-link kapag nailathala sa website ng Inquiry]. Tinitingnan ng ulat na iyon ang mga libing, libing, at kremasyon mula sa pananaw ng mga naulila noong panahon ng pandemya, habang sa ulat na ito ay nakatuon ang pansin sa mga karanasan ng mga manggagawa.

Mga pangunahing tema

Epekto ng pagpapatupad ng mga paghihigpit at gabay ng gobyerno

Pagbibigay-kahulugan at pagpapatupad ng gabay

Ang mga pangunahing manggagawa ay naharap sa mas matinding presyur noong panahon ng pandemya upang maunawaan at ipatupad ang nagbabagong mga paghihigpit at gabay. Kinailangan nilang umangkop nang mabilis, umako ng mga karagdagang responsibilidad tulad ng pagpapatupad ng pinahusay na mga protocol sa paglilinis, pagpapatupad ng social distancing, pagpapatupad ng mga mandato sa pagsusuot ng maskara at pamamahala ng mga pagbabago sa saklaw ng kanilang tungkulin. Sinasabing ito ang nagpataas ng stress sa mga pangunahing manggagawa sa isang mahirap nang sitwasyon, na lalong nagpalala sa kanilang mga karanasan ng stress.

| “ | Sabi [ng gobyerno] 'gusto naming ayusin ninyo ang mga libreng pagkain sa paaralan, kayo ang magiging eksperto sa kalusugan at kaligtasan, ayusin ang remote learning, gawin ang testing.' Napakaraming demand. Ang mga tao ay nagtatrabaho ng 20 oras sa isang araw… Napakaraming bagong demand na nagpahirap dito.”

– Pambansang Asosasyon ng mga Punong-guro (NAHT) |

Ang patnubay ay inilarawan bilang mabilis na nagbabago, kadalasan nang walang paunang abiso at sa mga hindi kombenyenteng oras tulad ng gabi ng Biyernes o katapusan ng linggo. Nangangahulugan ito na walang oras ang mga sektor upang maghanda o tumugon nang naaangkop. Ang mga madalas na pagbabago ay nag-iwan sa mga pangunahing manggagawa na hindi sigurado kung naipatupad ba nila nang tama ang mga patnubay.

| “ | Mayroong magkasalungat at magkasalungat na patnubay. Pagkalipas ng isang buwan, sasabihan ka na huwag gawin ang X, dapat mong gawin ang Y. Ang paglipat ng mga goal post ay isang problema.

– NAHT |

Binigyang-diin ng mga organisasyon na kapag nakikipag-ugnayan sila sa gobyerno tungkol sa mga nagbabagong sitwasyon at gabay, kung minsan ay inaabot ng ilang linggo bago tumugon ang mga departamento sa kanilang mga katanungan, na humahantong sa kawalan ng katiyakan at pangamba sa mga nagtatrabaho sa frontline.

Habang tumatagal ang pandemya, ang madalas na pag-update ng mga gabay ay humantong sa kalituhan at pagkadismaya sa mga pangunahing manggagawa. Madalas silang kailangang mabilis na umangkop sa mga bagong patakaran nang walang sapat na abiso, pagsasanay, o kalinawan. Ang kakulangan ng pag-unawang ito ay minsan humahantong sa mga komprontasyon sa publiko, na nalilito rin. Ang madalas na mga pagbabago ay nagdulot ng pagdududa sa ilang pangunahing manggagawa tungkol sa kredibilidad ng gabay.

| “ | Sa sandaling magsimulang magbago ang gabay, nagkaroon ng ganap na kawalan ng kredibilidad sa antas ng frontline. Masaya kaming ipatupad ang mga patakaran, ngunit pagkatapos ay nagbabago ang mga patakaran. Magbabago ba ulit ang mga ito?

– Pederasyon ng mga Awtoridad sa Paglilibing at Pagsusunog ng Bangkay (FBCA) |

Nabanggit ng mga kinatawan na ang mga unyon at mga ahensya ng kalakalan ay kadalasang umaasa sa pagbibigay-kahulugan sa gabay at pagbibigay ng angkop na payo sa mga organisasyon at pangunahing manggagawa. Ang suportang ito ay kinakailangan dahil mayroong malaking kakulangan sa kaalaman sa mga protocol sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho at kakulangan ng kahandaan sa mga employer sa panahon ng pandemya.

Ang pag-asa na ito sa mga unyon at mga sangay ng kalakalan ay nagpatuloy habang naglalabas ang gobyerno ng mas tiyak na patnubay. Nadama ng mga kinatawan na bihirang linawin ng patnubay kung ano ang kailangang unahin, na nag-iiwan sa mga manggagawa na nabibigatan at walang suporta. Ang patnubay ay hindi palaging ibinibigay sa iba't ibang wika upang matugunan ang mga pangunahing manggagawa na hindi nagsasalita ng Ingles, na nangangahulugan na marami ang hindi nakakaintindi ng mga protocol sa kaligtasan o sa kanilang mga karapatan sa pagtatrabaho. Dahil dito, sila ay partikular na mahina sa pagsasamantala ng mga employer at may mga halimbawa ng mga employer na pinipilit ang mga manggagawa na magtrabaho sa mga hindi ligtas na kondisyon.

| “ | [Mayroong] isang kompanya ng pagmamanupaktura na may mga manggagawang hindi talaga nagsasalita ng Ingles at [sinasabihan] nila silang pumasok sa trabaho, kahit na sila ay may sakit... Walang gabay sa puntong ito sa sektor, walang komunikasyon sa ibang wika maliban sa Ingles.

– Unyon ng GMB |

Tumutok sa: pulisya at hustisya

Sinabi ng mga kinatawan ng pulisya at hustisya na ang bilis ng mga pagbabago sa gabay ay nangangahulugan na walang oras para sa pinasadyang pagsasanay na karaniwang nagaganap para sa mga pagbabago sa batas. Nagpahayag ng mga alalahanin ang Police Federation na ang kakulangan ng kalinawan sa bagong gabay ay nag-iwan sa mga opisyal ng pulisya na hindi sapat ang kaalaman tungkol sa kung paano gagawin ang mga kinakailangang pagbabago sa mabilis na bilis. Nadama nila na naapektuhan nito ang kakayahan ng mga opisyal na ipatupad nang epektibo ang gabay.

| “ | Ang karaniwang nangyayari kapag may ipinakikilalang bagong batas, magkakaroon tayo ng 140,000 opisyal ng pulisya na siyang magsasagawa nito at magdidisenyo kayo ng pagsasanay. Dahil sa mga pangyayari, hindi natin ito magagawa.”

– Ang Pederasyon ng Pulisya |

Binigyang-diin ng UNISON ang isang pagkakaiba sa paraan ng pagsunod ng mga organisasyon ng pulisya, bilangguan, at probasyon sa mga kinakailangan ng regulasyon para sa pag-uulat ng mga alalahanin sa kalusugan at kaligtasan sa ilalim ng pag-uulat ng Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations (RIDDOR). Sinabi nila na ang mga puwersa ng pulisya ay nagpatupad ng isang sistema para sa pare-parehong pag-uulat ng pinaghihinalaang pagkalat ng Covid-19 sa lugar ng trabaho sa ilalim ng RIDDOR, habang ang mga serbisyo sa bilangguan at probasyon ay tumigil sa pagsusumite ng mga ulat dahil sa gabay ng Public Health England na may kaugnayan sa patunay na naganap ang pagkalat sa lugar ng trabaho.

| “ | Regular na naglalabas ang mga pulis ng mga ulat ng RIDDOR kung saan pinaniniwalaang nagkaroon ng transmisyon sa lugar ng trabaho. Hindi iyon ang kaso sa [HM Prison and Probation Service], sinusunod nila ang gabay ng [Public Health England]… labis kaming nalungkot tungkol doon… may mga insidente kung saan dalawang tao ang namatay habang nagtatrabaho sa iisang opisina sa loob ng maikling panahon… dapat sana ay may ulat ng RIDDOR na imbestigahan.”

– UNISON |

Tinukoy ng UNISON ang malaking epekto nito sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho at isinaalang-alang na ang kawalan ng pormal na pag-uulat ay maaaring makasira sa pagtukoy ng mga pattern ng pagkalat, na humahantong sa mas maraming tao na mahawaan ng Covid-19 sa lugar ng trabaho.

Tumutok sa: edukasyon

Sa sektor ng edukasyon, nagsalita ang mga kinatawan mula sa mga unyon kung paano sila nagtulungan upang lumikha ng mga checklist upang suportahan ang mga organisasyon sa pagsunod sa mga gabay at pag-unawa sa mga prayoridad. Nagbigay ang mga unyon ng pagsasanay sa bentilasyon, mga pagtatasa ng panganib at ang hirarkiya ng kontrol.2 upang suportahan ang mga miyembro at paaralan na maunawaan kung paano pinakamahusay na protektahan ang kanilang mga manggagawa.

Ipinaliwanag nila na isang kinakailangan sa batas sa kalusugan at kaligtasan ang pagkakaroon ng mga 'may kakayahang tao' na may mga kinakailangang kasanayan, kaalaman, at karanasan upang matukoy ang mga panganib sa lugar ng trabaho at mga hakbang sa pagkontrol upang protektahan ang mga tao mula sa pinsala.3 Sinabi ng mga kinatawan mula sa mga unyon na nagkaroon ng kawalan ng prayoridad at kakulangan sa pondo para sa mga propesyonal sa kalusugan at kaligtasan sa mga lugar ng edukasyon, na humantong sa kakulangan ng mga 'may kakayahang tao' bago ang pandemya. Nangangahulugan ito na ang sektor ay partikular na hindi handa upang protektahan ang mga tao sakaling magkaroon ng emergency.

| “ | Mahigit 1000 miyembro ang sumali sa mga panawagang ito – ang mga employer ay nagtatanong ng mga pangunahing bagay tulad ng kung ano ang risk assessment, itinuturo lang sa kanila kung ano iyon at ang herarkiya ng kontrol. Hindi kapani-paniwala na wala ang kaalamang iyon, mas malala ito kaysa sa inaakala namin. Madalas ay walang mga espesyalistang safety person sa site, inaasahan na mayroon nito ang mga manager.”

– Unyon ng Unibersidad at Kolehiyo (UCU) |

Sinasabing naapektuhan ang mga pagsisikap na isulong ang pag-unawa sa kalusugan at kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho dahil sa kakulangan ng gabay kung aling mga kontrol ang dapat unahin ng mga employer upang masunod nang epektibo ang isang hierarchy of control approach. Ang epekto nito ay ang mga kontrol tulad ng pinahusay na bentilasyon at paglilinis ng hangin tulad ng HEPA filtration ay hindi inuuna kaysa sa mas madali at mas mababang gastos na mga kontrol tulad ng paghuhugas ng kamay, sa kabila ng posibilidad na ang airborne transmission ay isang pangunahing ruta ng transmission. Iniulat na nagdulot ito ng alitan sa pagitan ng mga employer at mga unyon kung saan ang mga unyon ay nagtutulak para sa mas epektibong mga hakbang sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho, ngunit sinasabi ng mga employer na sinusunod nila ang gabay ng gobyerno.

| “ | Kung hindi mo naiintindihan ang papel ng bentilasyon, [maiiwan ka] sa maling katiyakan na 'patuloy na maghugas ng kamay.' Ang mga [pamamaraan sa kaligtasan] na mas mahirap gawin na makakagawa ng pagbabago ay isinantabi. Ang mga mas madaling bagay ay inuna. Kung ginugugol mo ang iyong mga araw sa loob nito tulad namin, naiintindihan namin ito, ngunit hindi namin maiparating ang mensaheng ito.

– Pambansang Unyon ng Edukasyon (NEU) |

Nang magsimula ang programa ng pagbabakuna, sinabi ng University and College Union (UCU) na maraming lugar ng edukasyon ang gumamit nito bilang katwiran para alisin ang lahat ng iba pang kontrol sa kaligtasan. Ang paniniwala na ang bakuna ay sapat na proteksyon para sa mga manggagawa sa mga lugar ng edukasyon ay inilarawan bilang humahantong sa hindi ligtas na mga kapaligiran sa pagtatrabaho.

Binigyang-diin din ng mga unyon sa edukasyon ang epekto ng mga pagkaantala sa paglalathala ng gabay para sa mga partikular na bahagi ng sektor ng edukasyon tulad ng mga paaralang nagtuturo sa mga batang may mga espesyal na pangangailangan at kapansanan sa edukasyon (SEND), mga tagapagturo na nagtatrabaho sa mga bilangguan at mga tagapagturo na nagtatrabaho sa mga nursery. Ang mga manggagawa sa mga setting na ito ay kinailangang maghintay nang mas matagal para sa gabay kumpara sa ibang mga paaralan.4Nang ilabas ang patnubay, nadama nila na hindi nito kinikilala ang mga natatanging gawain na kailangang gawin ng mga guro at kawani ng suporta sa pagkatuto, kabilang ang pagbibigay ng pangangalagang medikal o pagtulong sa mga mag-aaral na gumamit ng palikuran. Dahil dito, pakiramdam ng mga manggagawa ay nakalimutan sila at nag-aalala na hindi sila sumusunod nang maayos sa patnubay.

Sinabi ng NASUWT – Unyon ng mga Guro – na kakaunti ang gabay ng mga manggagawa sa pamamaraang dapat nilang gamitin (kabilang ang kaugnay ng mga pagsusulit) na humahantong sa kalituhan sa mga magulang at kawani ng edukasyon kung paano ihahanda ang mga mag-aaral.

| “ | Kulang ang gabay para sa mga manggagawa sa edukasyon, masyadong kulang, huli na ang lahat. Ang mga sitwasyong kinalalagyan nila sa trabaho ay hindi tatanggapin sa ibang lugar – ang ilang kawani ay malapit na nakikipag-ugnayan sa daan-daang mga mag-aaral sa isang araw. Ang mas malawak na gabay ay sadyang hindi angkop.

– NASUWT |

| “ | "Parang isang isla ang [Edukasyon] kumpara sa ibang sektor kung saan mayroong ilang uri ng pagkakapare-pareho. Iba ang patakaran tungkol sa mga maskara, test and trace, at iba pa... iyan ay isang matinding paghihiwalay para sa isang populasyon ng manggagawa na hindi nauunawaan. Sila [mga manggagawa sa edukasyon] ay nakaramdam ng pag-iisa at hindi pinapansin at pagkatapos ay nakaramdam ng pagsubok mula sa gobyerno."

– Kongreso ng Unyon ng mga Manggagawa (TUC) |

| “ | Ang laban na dapat marinig, sa palagay ko iyon ang kailangang baguhin sa susunod. Ang pinakamatinding halimbawa ay noong 2021 [noong Enero nang magbukas ang mga paaralan sa loob ng isang araw] nang pinayuhan namin ang aming mga miyembro isang araw bago magsara ang mga paaralan na ipadala ang Seksyon 44.5 mga abiso sa kanilang mga employer.”

– NEU |

Tumutok sa: transportasyon, pamamahagi at pag-iimbak

Mga kinatawan ng transportasyon, pamamahagi at pag-iimbak inilarawan kung gaano kabilis nila kinailangang bigyang-kahulugan at ipamahagi ang patnubay ng gobyerno sa kanilang mga miyembro, mga kinatawan ng kalusugan at kaligtasan, at mga indibidwal na operator ng transportasyon. Bagama't sinabi nilang ang ilang operator ay nagtulungan upang bigyang-kahulugan at ilapat ang patnubay, ang iba, lalo na ang mga pribadong kumpanya, ay kumilos nang mas malaya. Nagresulta ito sa patnubay na ipinatupad nang iba at kawalan ng komunikasyon tungkol sa pinakamahusay na kasanayan, na posibleng lumikha ng mga panganib sa kaligtasan para sa mga manggagawa.

Nagkaroon ng kakulangan ng kalinawan tungkol sa legal na katayuan ng patnubay na ginawa ng iba't ibang pamahalaan at mga pampublikong katawan na lumikha ng kalituhan sa mga manggagawa. Sa sektor ng transportasyon, pamamahagi, at pag-iimbak, binigyang-diin ng mga kinatawan ang mga hindi kinakailangang komplikasyon na kaakibat ng pagkakaiba sa pagitan ng patnubay, patakaran, at batas, na nagpapahirap sa pagtukoy kung aling mga hakbang sa kaligtasan ang ipinag-uutos at alin ang mga rekomendasyon.

| “ | Walang nakakaalam kung kaninong awtoridad ang magpatupad ng [pagsusuot ng maskara]. Ayaw ng mga tao na ilagay ang kanilang mga tauhan sa unahan ng pagpapatupad ng pagsusuot ng maskara. Habang nagbabago ang gabay, kinailangan mong sumang-ayon sa mga employer kung paano iyon gagana... Agad nitong inilalagay ang mga tao sa mga sitwasyon na may mas malaking panganib.

– Pambansang Unyon ng mga Manggagawa sa Riles, Maritima at Transportasyon (RMT) |

Tumutok sa: mga libing, libing at kremasyon

Tinalakay ng mga kinatawan mula sa sektor ng mga libing, paglilibing, at kremasyon kung paano lubos na binago ng mga paghihigpit at patnubay na inilabas ng gobyerno ang paraan ng pagsasagawa ng mga libing, na nagkait sa mga pamilya ng pagkakataon para sa mga tradisyonal na pamamaalam. Ipinagbawal ang mahahalagang kultural na ritwal tulad ng pagdalo sa mga serbisyo ng krematorium, pagdadala ng mga kabaong, pag-awit habang nagsasagawa ng mga seremonya, mga pamilyang magkakasamang naglalakbay sa mga prusisyon ng libing at pagtingin sa namatay bago ang libing o kremasyon. Sinabi ng mga nagtatrabaho sa loob ng sektor ng libing na nakakaramdam sila ng matinding pressure at isang matinding obligasyon na tiyakin ang marangal na pamamaalam para sa namatay, sa kabila ng mahigpit na mga paghihigpit na ipinatutupad.

| “ | Sinisikap naming tiyakin na mayroong koordinadong pagsisikap upang matiyak na ang mga taong namamatay ay tinatrato nang maayos... kinailangan naming kumilos upang matiyak na ang mga tao ay mabibigyan ng dignidad na nararapat sa kanila.

– Pambansang Konseho ng Libing (NBC) |

Binigyang-diin ng mga organisasyon na nang maglabas ng partikular na patnubay para sa sektor, nagbigay ito ng kalinawan at ginhawa sa pamamagitan ng pag-alis ng pasanin sa mga direktor ng punerarya, na dating napilitang gumawa ng sarili nilang mga desisyon tungkol sa kung paano dapat ilapat ang mga paghihigpit. Gayunpaman, patuloy na nagkaroon ng kalituhan, dahil nabigo ang patnubay na isaalang-alang ang mga pangangailangan ng sektor kaugnay ng mga kinakailangan sa paghawak para sa namatay.

Binigyang-diin din ng mga kinatawan ang mga hamon sa pagsasama-sama ng iba't ibang pananampalataya at kultural na kasanayan sa pamamagitan ng gabay ng gobyerno. Halimbawa, inilarawan ng kinatawan para sa National Burial Council (NBC) kung paano ang ritwal na paghuhugas ay isang mahalagang bahagi ng paghahanda para sa libing sa mga pananampalatayang Hudyo at Muslim at, bago ang pandemya, karaniwang isinasagawa ng mga matatanda mula sa pamilya o komunidad. Gayunpaman, kasunod ng pagpapakilala ng gabay ng gobyerno na hindi ito dapat gawin ng mga taong mahigit 60 taong gulang dahil sa mga panganib sa kalusugan, kinailangang mabilis na sanayin ng sektor ang mga nakababata. Nagdagdag ito sa workload at nagpataas ng pressure sa mga kawani sa panahon ng nakababahalang panahon. Kinailangan din nilang limitahan ang bilang ng mga taong nakikilahok sa paghuhugas ng mga bangkay.

| “ | Hindi kami makapaglagay ng team [para maghugas ng mga bangkay] dahil hindi puwedeng ganoon karami ang tao sa silid. Walang nakakaalam kung paano nahawa ang Covid-19. Para sa amin, talagang nakakapangilabot na hindi magawa ang huling bagay na iyon [paghuhugas] para sa isang tao dahil ito ay isang mahalagang bahagi ng aming proseso ng libing. Nakakapangilabot ito.”

– Samahang Pinagsamang Libing ng mga Hudyo (JJBS) |

Ang pagpapatupad at pagpapatupad ng mga paghihigpit sa bilang ng mga taong maaaring dumalo sa mga libing ay partikular na mahirap sa mga sitwasyon kung saan ang komunidad ng kultura o relihiyon ay karaniwang nag-oorganisa ng malalaking libing. Ipinaliwanag ng NBC na, para sa mga pamilyang Muslim, ang mga libing ay malalim na mga kaganapang pangkomunidad, na kadalasang dinadaluhan ng mas malawak na network ng mga kamag-anak at miyembro ng komunidad. Ang paglimita sa pagdalo ay hindi lamang nakagambala sa mga gawaing pangrelihiyon na ito kundi nagdulot din ng matinding emosyonal na pagkabalisa. Ang pagpapatupad ng mga paghihigpit ay naglagay sa mga kawani sa frontline sa mahihirap na posisyon,

na nangangailangan ng sensitibong negosasyon at kamalayang kultural at ang pangangailangang itaguyod ang dignidad, mga kaugaliang nakabatay sa pananampalataya, at mahabaging pangangalaga.

Binigyang-diin ng National Association of Funeral Directors (NAFD) kung paano ang mga tagubiling ibinibigay sa mga ahensya ng gobyerno, tulad ng Pandemic Multiagency Response Teams (PMART)6 at ang kakulangan ng pakikilahok ng mga direktor ng punerarya sa unang pagtugon sa mga pagkamatay dahil sa Covid, ay nagdulot ng pagkalito at pagkalito sa mga nagtatrabaho sa loob ng sektor, lalo na sa mga ruta ng pagkalat at mga kinakailangan sa ligtas na pagtatrabaho.

| “ | May isang maagang kaso ng isang paramedic na ipinadala upang beripikahin ang [isang] pagkamatay at isa pang opisyal upang tumulong sa… pagtatakip [sa] katawan mula sa itaas at ibaba gamit ang cable tie… Sinasabihan nila ang pamilya na huwag pumasok sa isang silid at makipag-ugnayan agad sa direktor ng punerarya. Ito ay naging problematiko dahil sa ilang kadahilanan: A) bakit may isang taong tinatrato nang ganoon? B) Pagkakakilanlan: paano natin makukumpirma ang pagkakakilanlan nang hindi binubuksan ang balot ng katawan? C) Pagtitiwala. Ang ahensya ng gobyerno na ito ay kumikilos nang ibang-iba sa sinasabi sa atin.”

– NAFD |

Binigyang-diin din nila na ang paghawak sa namatay alinsunod sa mga tagubiling ito ay itinuturing na walang pakialam, na nagdudulot ng matinding pagkabalisa kapwa sa mga pamilya ng mga namatay at sa mga direktor ng punerarya na dumalo.

Nagtulungan ang mga pinuno ng sektor upang bigyang-kahulugan ang gabay, na nag-aalok ng suporta at payo mula sa mga kapantay sa mga organisasyon. Ang kolaborasyong ito ay itinuring na mahalaga para mabawasan ang epekto sa mga negosyo, manggagawa, at mga serbisyong iniaalok nila sa mga nagdadalamhating pamilya.

| “ | Ang ating sama-samang pagsisikap ang nakagawa ng pagbabago. Sa pamamagitan ng pagtutulungan, natulungan nating matiyak na ang epekto ay hindi magiging kasingtindi ng maaaring mangyari kung hindi man.”

– NBC |

Itinampok din ng mga nasa loob ng sektor kung paano sa kasalukuyan ay walang iisang departamento ng gobyerno na responsable sa pangangasiwa ng mga serbisyo sa libing, kung saan ang iba't ibang aspeto ay nasa ilalim ng iba't ibang responsibilidad ng departamento. Nadama nila na ang pira-pirasong pamamaraang ito ay lumikha ng mga hamon sa koordinasyon at nangangahulugan na walang malinaw na punto ng pakikipag-ugnayan kung kailan inilabas ang patnubay.

| “ | Ang gobyerno, sa pangkalahatan, ay hindi humahawak sa mga libing. Walang departamento na humahawak sa mga libing.

– JJBS |

Tumutok sa: sunog at pagsagip

Inilarawan ng Fire Brigades Union (FBU) kung paano nila sinusubaybayan ang mga nangyayari bago ang unang lockdown at nag-ambag sa mga konsultasyon ng gobyerno tungkol sa mga paghihigpit sa pandemya, na nagbigay-daan sa kanila na magsimula ng mga talakayan sa mga employer dalawang linggo bago mailathala ang patnubay. Ang FBU, mga employer ng bumbero, at mga punong opisyal ng bumbero ay nakipagnegosasyon para sa isang pambansang kasunduan upang mapanatili ang regular na paggana ng interbensyong pang-emerhensya, habang pinapayagan ang mga bumbero na ligtas na magboluntaryo para sa mga karagdagang aktibidad na kinakailangan sa kanila. Ito ay napakahalaga para sa unang siyam na buwan ng pandemya sa pagtiyak ng kaligtasan ng mga manggagawa.

Gayunpaman, ang kakulangan ng espesipikong impormasyon sa loob ng gabay sa sunog at pagsagip ay nangangahulugan na mayroong iba't ibang interpretasyon kung paano dapat ipatupad ang mga hakbang sa mga lugar ng trabaho sa sunog at pagsagip. Ito ay inilarawan bilang partikular na mapanghamon kapag nagpapatupad ng social distancing at self-isolation at nakaapekto sa kung paano ipinapatupad ang mga hakbang sa kaligtasan ng Covid-19 sa mas pangkalahatang paraan.

| “ | Masasabi kong mayroon kaming 50 iba't ibang interpretasyon ng patnubay ng gobyerno mula sa bawat serbisyo ng bumbero at pagsagip.

– FBU |

Ang epekto ng magkasalungat na patnubay

Tumutok sa: mga libing, libing at kremasyon

Inilarawan ng sektor ng mga libing, paglilibing, at kremasyon kung paano, sa isang yugto, hindi pinapayagang buksan sa publiko ang mga sementeryo, maliban sa mga libing. Gayunpaman, ang ilang bakuran ng krematorium ay nanatiling bukas sa publiko para sa ehersisyo, pagbisita, at paglilibing. Lumikha ito ng mga problema sa operasyon para sa mga namamahala sa mga lugar na nag-aalok ng parehong serbisyo sa libing at kremasyon. Inilarawan din nila ang iba pang nakalilitong mga senaryo, tulad ng gabay na nagsasaad na ang mga sementeryo ay maaaring gamitin para sa pang-araw-araw na ehersisyo, habang ang pagdalo sa libing ay pinaghihigpitan pa rin. Naging mahirap para sa mga kawani ng sementeryo na pamahalaan at ipatupad ang iba't ibang mga patakaran para sa mga taong gumagamit ng parehong espasyo para sa iba't ibang layunin.

Nagkaroon din ng magkasalungat na impormasyon tungkol sa mga aspeto ng operasyon ng kanilang tungkulin, kabilang ang paggamit ng mga body bag at kung pinahihintulutan ang pag-embalsamo. Nagdulot ito ng kalituhan at hindi pantay-pantay na mga kasanayan sa buong sektor.

| “ | Nagbabago ang mga bagay-bagay araw-araw. Halimbawa, mga body bag: dalawa sa Northern Ireland, 1 sa England. Ano ang gagawin natin? ...Paano naman ang pag-embalsamar? Mga taong bumibisita?”

– Instituto ng Pamamahala ng Sementeryo at Krematorium (ICCM) |

Tumutok sa: pulisya at hustisya

Nagbigay ang kinatawan para sa UNISON ng isang halimbawa ng pagtanggap ng magkasalungat na gabay sa pagpapatupad ng social distancing at pagsusuot ng mask sa puwersa ng pulisya. Sinabi nila na sa simula ng pandemya, sinabihan ang pulisya ng National Police Coordination Centre7, na bilang isang panloob na lugar ng trabaho, kung saan hindi posible ang social distancing, dapat magsuot ng mga maskara. Pagkatapos ay nakatanggap sila ng patnubay mula sa Public Health England (PHE) na hindi kailangang magsuot ng mga maskara. Sinabi ng kinatawan na nagpasya ang puwersa ng pulisya na ipatupad ang pagsusuot ng maskara sa anumang pagkakataon upang protektahan ang kanilang mga manggagawa, ngunit sinabi nila na ito ay nagdulot ng kalituhan at nagpahina sa tiwala sa patnubay ng gobyerno.

Inilarawan ng kinatawan para sa National Police Chiefs' Council (NPCC) kung paano minsan sumasalungat ang gabay ng gobyerno sa umiiral na batas, na sa palagay nila ay nagiging dahilan upang hindi maipatupad ang gabay. Bagama't binanggit ng mga kinatawan na may mga pagpapabuti sa gabay sa paglipas ng panahon, sa palagay nila ay nananatili ang isyu na ang gabay ay kulang sa pag-unawa sa mga praktikalidad ng pagpapatupad nito.

| “ | Sa ilang pagkakataon, ang patnubay [ng gobyerno] ay hindi batas at mali talaga, na lumikha ng tunggalian noong sinusubukan naming ipatupad iyon sa antas ng publiko dahil palagi kaming sinusuri. [Ang NPCC] ay gumagawa ng mga patnubay na may katiyakan sa kalidad, legal na sinuri para magamit ng aming mga kawani sa frontline, at umabot sa puntong masasabi naming maliban kung dumaan ito sa prosesong iyon, hindi namin ito ipinapatupad.”

– NPCC |

Tumutok sa: edukasyon

Nagbigay ng mga halimbawa ng mga katulad na isyu ang mga kinatawan ng edukasyon. Sinabi nila na nakatanggap sila ng magkasalungat na patnubay mula sa iba't ibang departamento ng gobyerno at mga lokal na awtoridad. Ibabahagi rin ng mga magulang ang patnubay na natanggap nila mula sa kanilang sariling mga employer sa mga kawani ng edukasyon, na kung minsan ay sumasalungat sa patnubay na ibinibigay ng mga paaralan. Ang kakulangan ng kalinawan na ito ay lumikha ng kalituhan at nakadagdag sa workload ng mga kawani ng edukasyon habang sinusubukan nilang mag-navigate sa iba't ibang patnubay. Ang magkasalungat na patnubay ay nangangahulugan din ng kawalan ng kumpiyansa kung paano pinakamahusay na mapapanatili ng mga kawani ng edukasyon ang kanilang sarili, ang kanilang mga kasamahan at mga bata at kabataan na ligtas kapag pumapasok sa mga paaralan at kolehiyo nang personal.

Nagmuni-muni ang mga kinatawan tungkol sa epekto ng iba't ibang patakaran na ipinapatupad sa mga devolved na bansa at sa ilang mga kaso sa pagitan ng mga lokal na lugar ng konseho. Para sa mga manggagawang naninirahan sa hangganan ng isang bansa at nagtatrabaho sa isa pa, kinailangan nilang sundin at sundan ang dalawang magkaibang hanay ng gabay. Halimbawa, ang isang guro ay maaaring naninirahan sa Wales, ngunit ipinapatupad ang mga patakaran ng Ingles habang nagtatrabaho sa isang kapaligirang pang-edukasyon sa England. Nagdulot ito ng kalituhan tungkol sa kung aling gabay ang dapat sundin at ipatupad ng mga manggagawa sa loob ng kanilang mga lugar ng trabaho.

Itinaas ng UCU ang epekto ng paglalabas ng magkasalungat na patnubay para sa iba't ibang sektor ng edukasyon nang sabay-sabay. Nagsalita sila tungkol sa patnubay para sa sektor ng karagdagang edukasyon na hindi naaayon sa patnubay para sa sektor ng mas mataas na edukasyon, na lumilikha ng pagdududa at takot para sa mga manggagawa tungkol sa kung aling patnubay ang ibabatay sa agham at pananatilihin silang ligtas. May mga katulad na isyu para sa mga nagtatrabaho sa edukasyon sa bilangguan na may magkakaibang patnubay mula sa mga departamento ng gobyerno. Kinailangang bigyang-kahulugan ng UCU ang patnubay upang matukoy kung paano pinakamahusay na protektahan ang mga tagapagturo na nagtatrabaho sa mga bilangguan at mga institusyon ng mga batang nagkasala. Ang mga pagkakaiba sa pagitan ng patnubay para sa mga manggagawa sa opisina at mga kawani ng contact center sa mga setting ng edukasyon at mga kawani ng edukasyon ay lumikha ng karagdagang kalituhan tungkol sa kung ano ang ligtas.

Iniulat din ng mga kinatawan ng edukasyon na hindi malinaw kung saan legal na nakapaloob ang gabay patungkol sa batas sa kalusugan at kaligtasan, lalo na kung saan pinapahina ng gabay ang ilan sa mga kontrol sa mas mataas na antas na kadalasang natutukoy sa mga pagtatasa ng panganib sa lugar ng trabaho. Naging mahirap para sa mga unyon na magpayo kung ano ang magpapanatili sa kaligtasan ng mga manggagawa sa iba't ibang setting, na humahantong sa mga makabuluhang pagkakaiba sa aplikasyon ng gabay sa buong sektor.

Nagkaroon ng pinagkasunduan ang lahat ng unyon sa edukasyon tungkol sa mapaminsalang epekto ng muling pagbubukas ng mga paaralan sa loob lamang ng isang araw noong ika-4 ng Enero 2021. Sumang-ayon sila na ang mabilis at malaking pagbabagong ito sa gabay ay lubos na nagpahina sa tiwala sa mga patakaran ng gobyerno tungkol sa edukasyon, na naging dahilan upang labis na mag-alala ang mga kawani tungkol sa kanilang kalusugan at kaligtasan at sa potensyal na pagkalat ng Covid-19 sa iba pa sa kanilang mga tahanan.

| “ | Noong ika-4 ng Enero, sa gitna ng pandemya, inakala ng mga guro na hindi na sila babalik. Ina-update na mismo ng mga guro ang [gabay] at inaasahang babalik na sila sa trabaho sa araw na iyon… ang mensahe mula sa gobyerno ay 'babalik kayo' at pagkatapos ay hindi na pala.

– NASUWT |

Tumutok sa: tingian

Ang mga negosyong tingian na may mga tindahan sa buong UK ay kinailangang sumunod sa iba't ibang mga patakaran sa bawat bansa at subukang ipabatid ang mga ito nang tumpak sa kanilang mga manggagawa. Nagdulot ito ng hindi kinakailangang komplikasyon, pagtaas ng workload para sa mga negosyo, at kalituhan sa mga kawani.

Paggawa nang malayuan

Tumutok sa: edukasyon

Sa sektor ng edukasyon, ang mga paghihigpit sa lockdown dahil sa Covid-19 ay nangailangan ng paglipat sa online learning, kasabay ng pagtuturo sa mga pangunahing manggagawang bata sa mga paaralan at kolehiyo. Sinabi ng mga kinatawan na ang online learning ay humantong sa mga isyu sa pangangalaga para sa parehong kawani at mga mag-aaral. Sa partikular, may mga alalahanin tungkol sa privacy dahil sa mga estudyanteng nagre-record ng mga online lesson nang walang pahintulot, na nagpaparamdam sa mga kawani ng edukasyon na hindi komportable. Binigyang-diin ng NASUWT na ang paglipat sa online learning ay nagpalabo rin sa mga propesyonal na hangganan, dahil ang mga impormal na setting ng mga tahanan ng mga mag-aaral at kawani ng edukasyon ay hindi palaging angkop na kapaligiran sa pag-aaral.

Binigyang-diin ng mga kinatawan ang paglipat sa online learning noong panahon ng pandemya na naglantad sa mga hindi pagkakapantay-pantay sa pag-access sa mga mahahalagang device, tulad ng mga laptop, para sa parehong mga manggagawa at estudyante. Tinukoy nila ang mga hadlang sa pag-access at paggamit ng teknolohiya dahil sa mga limitasyon sa pananalapi, hindi sapat na pamumuhunan sa teknolohiya at hindi maaasahang koneksyon sa internet. Nabanggit ng NASUWT na ang teknolohiyang ibinibigay ng mga paaralan ay kadalasang hindi sapat, na pinipilit ang mga kawani ng edukasyon na bumili ng sarili nilang kagamitan, na siyang nagpabigat sa kanilang personal na pananalapi.

Sinasabing ang paglipat sa malayuang pagtuturo noong panahon ng pandemya ay nagpakita ng malaking kakulangan sa kahandaan at kawalan ng malinaw na gabay, lalo na tungkol sa mga isyu sa kalusugan at kaligtasan, pagsunod sa batas sa personal na datos, at suporta para sa mga mag-aaral ng SEND. Sinabi ng mga kinatawan na lumikha ito ng karagdagang presyon sa mga kawani ng edukasyon na kinailangang harapin ang mga hamong ito nang walang wastong suporta o malinaw na mga protokol.

| “ | May palagay noon na lahat ay maaaring maghatid ng online learning kahit na hindi sila sinanay at walang angkop na kagamitan… maraming miyembro ang nagmamadaling bumili ng sarili nilang laptop. Madalas na nasusumpungan ng mga guro ang kanilang mga sarili na walang pribadong espasyo para magturo, at pagkatapos ay hindi patas na napapailalim sa masusing pagsisiyasat at mga reklamo mula sa mga magulang tungkol sa kung paano sila nagtuturo.”

– NASUWT |

Binigyang-diin ng NASUWT ang epekto ng malayuang pagkatuto sa mga bagong kwalipikadong guro, na kadalasang nahihirapang bumalik sa silid-aralan, dahil karamihan sa kanilang karanasan sa pagtuturo ay online. Marami sa mga gurong ito ang umalis na sa propesyon, na nagpapakita ng pangmatagalang epekto ng pandemya sa mga manggagawa sa edukasyon.

Iniulat ng mga unyon na ang mga manggagawang clinically vulnerable (kabilang ang mga buntis) na pinayuhan ng gobyerno na mag-shield ay, sa halos lahat ng bahagi, protektado mula sa pagpasok sa mga paaralan at pinapayagang magtrabaho nang malayuan. Gayunpaman, sinabi ng NASUWT na ang kanilang mga miyembro na may dati nang mga kondisyon sa kalusugan, ngunit walang mga sulat na nagpapayo sa kanila na mag-shield, o ang mga nag-aalaga sa mga miyembro ng pamilya na clinically vulnerable, ay madalas na kailangang ipaglaban ang kanilang karapatan na magtrabaho nang malayuan. Binigyang-diin nila ang pagkabalisang dulot nito para sa mga kawani ng edukasyon sa mga sitwasyong ito.

Pokus sa: pulisya, hustisya at serbisyo sibil

Inilarawan ng Public and Commercial Services Union (PCS) kung paano sa buong Serbisyo Sibil ay may iba't ibang pamamaraan sa pagbibigay ng mga laptop at IT system upang paganahin ang mga pangunahing manggagawa na magtrabaho mula sa bahay. Bagama't ang ilang mga departamento ng gobyerno tulad ng Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) at HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) ay mabilis na nakapag-deploy ng mga laptop at kagamitan sa pagtatrabaho sa bahay, ang ibang mga departamento ng gobyerno ay kulang sa karagdagang mga laptop o imprastraktura upang suportahan ang remote working. Nangangahulugan ito na ang ilang mga manggagawa ay kinailangang magpatuloy sa pagtatrabaho sa mga opisina, makihalubilo sa mga kasamahan at publiko, na naglalagay sa kanila sa panganib na mahawaan ng Covid-19.

| “ | Maswerte talaga ang teknolohiya, depende sa imprastraktura, at kung kailangan mong pabilisin ang pag-unlad... Natapos naman ito sa tamang panahon pero sa unang 2-3 buwan, medyo mahirap para sa mga organisasyon kung hindi pa sila handa para sa remote working, kahit na gusto nilang magkaroon ng access sa mga bagay-bagay.”

– NPCC |

Tinalakay din ng PCS na, para sa sektor ng pulisya at hustisya, hindi laging malinaw mula sa gabay kung aling mga manggagawa ang maaaring magtrabaho mula sa bahay at kung aling mga pangunahing manggagawa ang kinakailangang dumalo sa trabaho nang personal. Ang kakulangan ng kalinawan na ito ay humantong sa mga pagkaantala sa pagtatakda, kung saan at paano, dapat magtrabaho ang mga kawani sa panahon ng pandemya.

| “ | Walang kalinawan kung aling mga grupo ng tao ang sinasabi ng gobyerno na dapat talagang magtrabaho sa bahay. Kaya, ang mga interpretasyon ay isang bangungot, at medyo natagalan bago iyon naunawaan.”

– Mga PC |

Tumutok sa: tingian

Inilarawan ng mga kinatawan sa sektor ng tingian kung paano nagsimulang lumitaw ang mga tensyon sa pagitan ng mga taong kayang magtrabaho nang malayuan (karaniwan ay ang mga nasa mas senior/managerial na posisyon o nasa mga tungkuling administratibo) at ng mga hindi kayang magtrabaho (karaniwan ay ang mga nasa frontline). Sinabi nila kung gaano ito kawalang-katarungan para sa mga kawani sa frontline at kung minsan ay binibigyang-diin ang hierarchical na istruktura ng kanilang lugar ng trabaho.

| “ | May isang pabrika sa York kung saan ang mga manggagawa sa talyer ay karamihang mga itim na manggagawa at mga puting manggagawa sa pamamahala. Napakabilis na nakakapagtrabaho ang mga pamamahala mula sa bahay at bihirang pumasok sa lugar ng trabaho. Ang mga pananaw at alalahanin na ibinahagi mula sa mga manggagawa [sa talyer] ay hindi pinakinggan at nagkaroon kami ng tunay na problema sa mga pagsiklab ng sakit sa lugar na iyon.

– Unyon ng mga Manggagawa sa Tindahan, Distributibo at Kaalyado (USDAW) |

Epekto sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho

Mga hakbang sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho

Sa mga unang yugto ng pandemya, sinabi ng mga kinatawan na ang gabay at suporta ng gobyerno upang protektahan ang mga manggagawa mula sa pagkahawa ng Covid-19 ay napakalimitado. Ipinaliwanag nila na kakaunti ang kaalaman tungkol sa virus at kung paano ito nalilipat na nangangahulugan na ang mga hakbang sa kaligtasan ay kadalasang hindi pare-pareho at hindi epektibo. Halimbawa, inilarawan ng mga kinatawan para sa mga manggagawa sa tingian kung paano sa mga unang yugto ng pandemya, pinayuhan ang mga manggagawa na ibalot ang mga t-shirt sa harap ng kanilang mga bibig sa halip na gumamit ng mga face mask. Ipinakita nila na ipinapakita nito ang kakulangan ng pag-unawa kung paano maiiwasan ang pagkalat ng virus at mailalagay sa panganib ang mga manggagawa.

| “ | Nakikipag-usap kami sa Health and Safety Executive nang maaga tungkol sa gabay, ngunit sinabihan kami na wala nito dahil ito ay isang isyu sa kalusugan ng publiko. …Hindi maipapatupad ang gabay ng gobyerno, kaya nasa sitwasyon ka kung saan ang karamihan sa mga manggagawang nasa trabaho at hindi nagtatrabaho sa sektor ng edukasyon o kalusugan ay halos walang proteksyon na ngayon.”

– Unyon ng GMB |

Tumutok sa: mga libing, libing at kremasyon

Isang malaking alalahanin para sa mga manggagawa sa libing, libing, at kremasyon ay ang pagpapasya kung paano ligtas na makikipagtulungan sa mga yumaong taong maaaring namatay dahil sa Covid-19. Kabilang dito ang pamamahala sa mga panganib sa kanilang sariling kalusugan na nauugnay sa pagkolekta, paghawak, at paghahanda ng mga bangkay, pati na rin ang mga panganib sa pagkalat nito sa kanilang mga mahal sa buhay o kasamahan. Sa mga unang yugto ng pandemya, ang mga manggagawa sa libing, libing, at kremasyon ay hindi sinabihan kung ang mga tao ay namatay mula sa o may Covid-19 dahil sa mga patakaran sa pagiging kumpidensyal ng doktor-pasyente. Nangangahulugan ito na hindi maayos na masuri ng mga manggagawa ang kanilang sariling panganib ng pagkakalantad sa Covid-19 o ang panganib ng pagkahawa sa iba.

| “ | Sa mga unang yugto, hindi sinabihan ang mga manggagawa sa pagdadalamhati kung ang mga indibidwal ay namatay dahil sa Covid-19, na naglilimita sa kanilang kakayahang masuri ang mga panganib ng pagkakalantad. Sa mga huling yugto lamang pinayagan ang mga registrar na ibunyag ang impormasyong ito.

– NBC |

Binigyang-diin din ng sektor ng mga libing, paglilibing, at kremasyon na ang panganib ng pagdalo ng mga taong positibo sa Covid sa mga libing ay nakadagdag sa stress ng mga nagtatangkang magsagawa ng mga serbisyo sa libing, sa panahon ng pangkalahatang kawalan ng katiyakan.

| “ | [Mayroong] dalawang [panganib]: [ang] namatay at ang mga panganib na ito, at ang mga buhay na taong nakakasalamuha mo sa mga sitwasyong ito.

– ICCM |

Medyo natagalan bago mailabas ang gabay sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho para sa kanilang sektor at humantong ito sa iba't ibang pamamaraan ng mga organisasyon upang subukang protektahan ang mga manggagawa. Sinabi nila na ang mas malalaking negosyo ay may posibilidad na magkaroon ng mas mahigpit na mga protocol sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho bilang paraan ng pamamahala ng panganib ng korporasyon. Nang mailabas ang gabay sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho, hindi ito kasinghigpit ng mga hakbang sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho na ipinasiya ng ilang organisasyon sa sektor na ipatupad, na partikular na mahirap ipaliwanag sa mga frontline worker.

| “ | Nang dumating ang gabay mula sa gobyerno, mukhang mas magaan na ito kaysa sa napagpasyahan ng mga tao na kailangan nila. Matagal bago natiyak sa mga tao na ayos lang ang lahat.”

– NAFD |

Tumutok sa: transportasyon, pamamahagi at pag-iimbak

Para sa sektor ng transportasyon, distribusyon, at pag-iimbak, ang mga ipinapatupad na hakbang sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho ay nakadepende sa mga partikular na tungkulin at iba-iba ayon sa organisasyon, kabilang ang kung ang mga kumpanya ay pribado o pampublikong pag-aari. Binigyang-diin ng Union of Shop, Distributive and Allied Workers (USDAW) na ang paggamit ng mga third-party logistic company at subcontracted workforce ay lalong nagpahirap na matiyak na ang mga protocol sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho ay palaging nasusunod. Ang National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers (RMT) ay nagbigay ng isang halimbawa ng isang kumpanya ng bus na gumagamit ng plastic shower curtain upang paghiwalayin ang mga drayber mula sa mga pasahero, na sinabi nilang hindi epektibo.

Binigyang-diin nila na ang ilang bodega at pabrika, na may maalikabok na kondisyon at malapit na pakikisalamuha sa mga manggagawa, ay nahaharap sa mas mataas na pagkakalantad sa Covid-19 at mga panganib sa impeksyon na may sterile. Sa kabaligtaran, ang mga lugar ng paggawa ng pagkain ay nakatuon na sa kalinisan at pinapanatili ang isang mas sterile na kapaligiran. Nangangahulugan ito na mas mahusay nilang maipapatupad ang mga karagdagang hakbang sa kaligtasan tulad ng pagsusuri ng temperatura ng katawan, mga testing center, at mga isolation room upang protektahan ang mga kawani.

Tumutok sa: edukasyon

Naisip ng mga kinatawan ng edukasyon na hindi sapat ang kalinawan ng papel ng Health and Safety Executive (HSE) noong panahon ng pandemya, na nangangahulugang hindi alam ng mga organisasyon kung maaari silang pumunta sa HSE upang humingi ng gabay. Humantong ito sa hindi pare-parehong mga kasanayan sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho at kawalan ng pagsunod sa kaligtasan sa mga lugar ng trabaho. Nais ng mga kinatawan na magkaroon ng mas malaking papel ang HSE sa pagpapanatiling ligtas ng mga manggagawa mula sa pagkahawa ng Covid-19 at sa pagpapanagot sa mga organisasyon para sa mga paglabag sa mga protocol sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho.

Ang ilang mga kinontratang manggagawa sa mga lugar ng edukasyon, tulad ng mga gurong nagsusuplay o kawani ng paglilinis, ay hinihiling pa ring magtrabaho sa maraming lokasyon halimbawa sa maraming paaralan sa isang trust, o sa mga kampus ng unibersidad. Nagpataas ito ng panganib ng impeksyon at pagkalat ng Covid-19 sa mga lugar ng edukasyon.

Mga hakbang sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho habang niluwagan ang mga paghihigpit

Habang nagpapatuloy ang pandemya, may persepsyon na ang kaligtasan ng mga manggagawa ay naging hindi gaanong prayoridad. Ito ay isang lumalaking pag-aalala habang ang mga pangkalahatang paghihigpit dulot ng pandemya ay nagsimulang lumuwag, na nag-iiwan sa mga pangunahing manggagawa sa ilang sektor na lalong nakakaramdam ng kahinaan sa pagkahawa ng Covid-19.

Tumutok sa: tingian

Nagkaroon ng kalituhan sa mga manggagawa sa tingian nang bawasan ang mga alituntunin sa social distancing mula dalawang metro patungong isang metro noong Hulyo 2020, habang nanatiling mandatory ang pagsusuot ng mga maskara sa mga lugar ng tingian. Pinaniniwalaan na ang partikular na pagbabagong ito ay sumira sa tiwala ng mga manggagawa sa tingian sa gobyerno at sinira ang kanilang tiwala sa gabay.

| “ | Ang gabay ay naging lubhang nakakalito, kung nanatili lang sila sa iisang mensahe. Ang 2 metro hanggang 1 metro pataas, para sa akin, ang simula ng tunay na epekto sa aming mga miyembro sa lugar ng trabaho.”

– Unyon ng mga Manggagawa sa Panaderya, Pagkain at Alyado (BFAWU) |

Tumutok sa: transportasyon, pamamahagi at pag-iimbak

Nakaramdam ng matinding pressure ang mga manggagawa sa sektor ng transportasyon, distribusyon, at pag-iimbak na bumalik sa normal na operasyon. May persepsyon sa sektor na inuuna ang ekonomiya kaysa sa kaligtasan ng mga manggagawa, na lumilikha ng kapaligirang puno ng takot at kawalan ng katiyakan.

| “ | Palagi kaming nag-aalala tungkol sa kung ano ang nagtutulak sa mga pagbabago sa gabay. Ang lahat ng bagay sa likod ng mga pagbabago ay hinihimok ng kanilang pagnanais na buksan ang ekonomiya. Iyon ang nangingibabaw sa kahalagahan ng kaligtasan.

– RMT |

Kagamitang Pangproteksyon sa Sarili (PPE)

Sa iba't ibang sektor, may mga halimbawa ng mga manggagawang hindi binigyan ng prayoridad para sa Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) noong mga unang bahagi ng pandemya at ibinahagi ng mga kinatawan ang epekto nito sa kanila. Ang kakulangan ng mga suplay ng PPE ay nagdulot ng pakiramdam ng ilang manggagawa na sila ay hindi ligtas at minamaliit.

Tumutok sa: edukasyon

Binigyang-diin ng mga kinatawan ng edukasyon kung paano nag-aalala ang mga nagtatrabaho sa mga paaralan para sa kanilang sariling kaligtasan dahil sa kakulangan ng PPE kapag nakikipagtulungan sa mga estudyante. Ipinaliwanag nila kung paano karamihan sa mga estudyanteng pumapasok sa paaralan sa panahon ng mga lockdown ay mga anak ng iba pang mahahalagang manggagawa, na marami sa kanila ay nagtatrabaho sa mga sektor ng kalusugan at pangangalagang panlipunan. Nakita ito ng mga nagtatrabaho sa mga paaralan bilang isang malaking panganib.

| “ | Noong una ay sinabihan ang mga kawani ng paaralan na hindi nila kailangan ng PPE. Walang naisip na mga kawani ang magbibigay ng pangangalaga, tulad ng mga first aider at mga nakikitungo sa mga mahihinang bata.

– Unyon ng GMB |

Pinag-usapan din nila kung paano hindi naipatupad ang pinakamabisang mga hakbang sa pangangalaga sa paghinga. Halimbawa, kinakailangang magsuot ng surgical mask ang mga guro, sa halip na mga FFP3 mask na sana'y makapagbibigay ng mas mahusay na proteksyon.

Itinala ng UNISON at UCU ang hindi proporsyonal na epekto ng pandemya sa mga kawani ng suporta, kabilang ang mga kawani ng suporta sa pag-aaral, kawani ng aklatan, mga tagapamahala ng hall of residence, mga propesyonal na kawani ng administratibo, mga drayber ng bus, mga tagalinis at mga kawani ng catering sa mga setting ng edukasyon, na pawang nagtatrabaho sa mga tungkuling malapitang makipag-ugnayan. Sinabi ng kinatawan ng UNISON na ang mga kawani ng suporta na ito ay hindi kasama sa listahan ng mga pangunahing manggagawa sa simula at nangangahulugan ito na hindi sila nakatanggap ng suporta sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho na kailangan nila, kabilang ang prayoridad na pag-access sa PPE. Ito ay kalaunan ay inamyendahan kasunod ng interbensyon ng mga unyon.

| “ | Siksikan ang mga kawani ng catering sa mga kusina. Walang anumang PPE, kung mayroon man. May mga ulat kami tungkol sa isang manager sa isang pribadong kontrata sa paglilinis na nagtatangkang suhulan ang mga kawani para umalis sa unyon kapalit ng pagkakaloob ng mga pangunahing PPE.

– UNISON |

Tumutok sa: mga libing, libing at kremasyon

Inilarawan ng sektor ng libing, paglilibing, at kremasyon ang mga katulad na isyu sa pag-access sa PPE, dahil ang mga kawani ay hindi paunang inuri bilang mga pangunahing manggagawa. Kinailangang gumamit ang mga organisasyon ng mga komersyal na ruta o mga umiiral na network upang subukang makakuha ng mga suplay at hindi ito palaging matagumpay.

| “ | Walang malinaw na mandato mula sa gobyerno na nagsasabing ito ay isang sektor na nangangailangan ng pagkakaloob ng PPE… Dahil dito, ang buong sektor ng punerarya ay walang anumang kakayahan, maliban sa kakayahang pangkomersyo, na makakuha ng PPE.”

– FBCA |

| “ | Kami [ang sektor ng mga libing, libing, at kremasyon] ay hindi pinansin. Bukod sa NHS at mga manggagawa sa pangangalaga, kami ang pinakanaapektuhan.”

– JJBS |

Tumutok sa: transportasyon, pamamahagi at pag-iimbak

Sinabi ng sektor ng transportasyon, distribusyon, at pag-iimbak na ang pag-access sa PPE ay lubhang iba-iba. Inilarawan ng RMT ang hindi pantay-pantay na probisyon ng PPE sa buong workforce ng transportasyon, kabilang ang kakulangan ng suplay para sa mga nagtatrabaho sa mga bus at hindi sapat na suplay at kalidad ng PPE para sa mga kawani ng paglilinis. Dahil dito, pakiramdam ng mga manggagawa ay nalantad at minamaliit ang kanilang halaga.

| “ | Nagsagawa kami ng survey noong 2021; ang pandemya ay umiiral nang wala pang isang taon at lahat ng mga problema ng hindi pagsunod sa gabay [sa sektor ng bus]. Sinuri namin sila nang mga sumunod na taon at karamihan sa kanila ay walang anumang PPE, karamihan sa kanila ay ganap na hindi kumbinsido na ang kanilang kumpanya ay may ideya tungkol sa gabay... Sinukat namin ang antas ng kumpiyansa ng mga manggagawa at sa mga bus ito ay napakababa.

– RMT |

Tumutok sa: pulisya at hustisya

Inilarawan ng Prison Officers Association (POA) kung paano sumalungat ang gabay sa paggamit ng PPE sa mga bilangguan sa Scotland at Northern Ireland sa payo na sumasaklaw sa England at Wales. Nagdulot ito ng mga pagkakaiba sa antas ng proteksyon para sa mga manggagawa sa bilangguan sa buong UK.

| “ | Dinadala namin ang mga bilanggo sa ospital na may Covid-19 at nakasuot ng karaniwang PPE na inisyu sa mga bilangguan at [ang mga manggagawa] ay hinarang sa ospital at sinabihan na hindi sila maaaring pumasok dahil hindi sila nakasuot ng 'tamang PPE'.

– POA |

Sumang-ayon ang mga kinatawan na ang patuloy na komunikasyon mula sa mga nakatataas na liderato tungkol sa mga hakbang sa kaligtasan at PPE ay nagkaroon ng positibong epekto sa pagpigil sa pagkalat ng Covid-19 at mga pagkamatay sa mga lugar ng pulisya at hustisya. Gayunpaman, nadama ng kinatawan ng UNISON na may mga isyu sa pagkakaroon at kalidad ng PPE sa sektor, lalo na sa mga unang bahagi ng pandemya, kung saan kung minsan ay hindi alam ng mga manggagawa na ang kagamitang ibinigay sa kanila ay hindi kasing pamantayan ng iba pang mga serbisyong pang-emerhensya.

| “ | Ang kawalan ng kahandaan ng karamihan sa mga serbisyong pampubliko upang harapin ang pandemya ay isa ring pangunahing problema noong unang bahagi ng pandemya, lalo na ang kakulangan ng PPE at ang mga pagkaantala dahil sa logistik pati na rin ang payo kung ano ang angkop na PPE sa mga partikular na sitwasyon.

– UNISON |

Paghihiwalay sa sarili at pagsusuri

Tumutok sa: transportasyon, pamamahagi at pag-iimbak

Inilarawan ng mga sektor ng transportasyon, distribusyon, at pagbobodega kung paanong ang isang malaking bilang ng mga tauhan ay "nai-ping"8 ng NHS Covid-19 contact tracing app9 Nagdulot ito ng malaking kakulangan sa mga tauhan. Sinabi nila na ang pagkaantala na ito ang nag-udyok sa ilang organisasyon ng transportasyon na hilingin sa kanilang mga manggagawa na i-disable ang app, na nagdulot ng pag-aalala at kawalan ng tiwala sa mga manggagawa.

| “ | Ang Test and Trace app ay naging isang tunay na problema para sa industriya ng riles… dahil napakaraming tao ang na-ping at inaasahang mag-self-isolate. Kung lahat ng na-ping ay nag-self-isolate, magsasara ang buong sektor.”

– RMT |

Pinayuhan ng programa ng contact tracing ang mga kawani na mag-self-isolate sa loob ng sampung araw kapag may 'ping' ngunit kalaunan ay ipinakilala ng gobyerno ang isang programang Test and Release kung saan maaaring kumuha ang mga kawani ng lateral flow Covid-19 test at kung negatibo, mas maagang makabalik sa trabaho, na nakakatulong upang matugunan ang kakulangan ng mga manggagawa. Gayunpaman, ikinagalit ito ng maraming manggagawa, na nakita ang mga pagbabagong ito bilang pagbibigay-priyoridad sa mga pangangailangan sa operasyon kaysa sa kaligtasan ng mga manggagawa.

Tumutok sa: edukasyon

Nag-ulat ang mga kinatawan ng edukasyon ng mga katulad na isyu, kung saan hindi tiyak ang mga guro at kawani ng suporta kung dapat ba nilang sundin ang gabay sa paghihiwalay ng NHS Covid-19 contact tracing app. May mga ulat na hiniling sa ilang manggagawa sa edukasyon na tuluyang i-disable ang app, para manatili sila sa lugar ng trabaho.

| “ | Sinabihan ang mga guro na dapat silang mag-isolate gamit ang [NHS Covid-19 contact tracing] app at pagkatapos ay sinabihan sila na hindi ito dapat ilapat sa mga manggagawa sa paaralan at dapat nilang i-off ang app.

– Unyon ng GMB |

Tumutok sa: pulisya at hustisya

Binigyang-diin din ng UNISON ang kalituhan sa mga puwersa ng pulisya patungkol sa NHS Covid-19 contact tracing app. Mayroong magkasalungat na payo sa loob ng sektor kung dapat bang i-activate ang app o hindi, na humantong sa hindi pagkakapare-pareho sa mga puwersa ng pulisya at kalituhan sa mga kawani.

| “ | Nais ko ring tukuyin ang NHS Track and Trace dahil may ilang pwersa ng pulisya na, noong una pa… ay nagmungkahi sa mga kawani sa mga kritikal na tungkulin na dapat nila itong patayin… dahil may pag-aalala tungkol sa kawalan ng abala mula sa lugar ng trabaho at ang pangangailangang mag-self-isolate… ang NPCC10 Malinaw na dapat panatilihing naka-on ang Test and Trace app sa trabaho ng mga kawani at opisyal at hindi ito labag sa batas na gumagana.”

– UNISON |

Tumutok sa: sunog at pagsagip

Tinukoy ng FBU ang mga kahirapan sa pagsunod sa gabay sa self-isolate sa konteksto ng kakulangan ng mga tauhan. Ipinaliwanag nila na ito ay isang pinagmumulan ng tensyon sa sektor dahil ang mga serbisyo ng bumbero at pagsagip ay hindi hinihikayat ang self-isolation sa simula ng pandemya dahil sa mga pressure sa mga serbisyo. Inilarawan nila kung paano ang National Fire Chiefs' Council11 ay naglalayong bawasan ang mga hakbang na may kaugnayan sa mga kinakailangan sa self-isolation at pagsusuri para sa mga kawaning nagsasagawa ng 'mga karagdagang aktibidad', tulad ng trabaho sa mortuary o pagmamaneho ng ambulansya. Mariing hindi sumang-ayon ang mga bumbero sa mga pagbabagong ito, dahil sa pangambang mas mataas ang panganib ng pagkalat ng Covid-19 sa mga hindi nagsasagawa ng 'mga karagdagang aktibidad' kapag bumalik sila sa kanilang mga lugar ng trabaho sa istasyon ng bumbero para sa kanilang mga regular na tungkulin.

Ang mga pinababang hakbang na ito ay partikular na naging problematiko para sa mga manggagawang may dati nang mga kondisyon sa kalusugan o mga responsibilidad sa pangangalaga, na nag-aalala tungkol sa kanilang sariling pagtaas ng panganib ng malubhang sakit at pagkahawa sa mga mahihinang miyembro ng pamilya. Sa ilang mga kaso, sinasabing humantong ito sa aksyong pandisiplina laban sa mga bumbero at kawani ng kontrol na gustong mag-self-isolate upang protektahan ang isang mahal sa buhay. Lalong lumala ang sitwasyon nang, noong huling bahagi ng 2020, ang NFCC at pagkatapos ay ang mga employer ng bumbero ay tumalikod sa pambansang kasunduan na ginawa sa pagitan ng FBU, mga employer ng bumbero at mga punong opisyal ng bumbero. Ang pambansang kasunduang ito ay napagkasunduan upang mapanatili ang regular na paggana ng interbensyong pang-emerhensya, habang nagbibigay-daan sa mga bumbero na ligtas na magboluntaryo para sa mga karagdagang aktibidad na kinakailangan sa kanila.

| “ | Mayroong presyur na ipagawa sa mga bumbero ang regular na trabaho, dagdag pa ang parami nang parami ng mga karagdagang aktibidad ngunit isinasakripisyo ang kaligtasan.”

– FBU |

Pagpapanatili ng pagitan mula sa kapwa-tao

Tumutok sa: edukasyon

Tinalakay ng mga kumakatawan sa sektor ng edukasyon kung paano nagkaroon ng palagay sa publiko na sarado ang mga paaralan, kolehiyo, unibersidad, at iba pang mga lugar ng edukasyon noong panahon ng pandemya, kung saan sinusuportahan ng mga kawani ang online na pag-aaral mula sa bahay. Hindi ito ang kaso, dahil maraming kawani, na ang ilan ay klinikal na mahina, ang patuloy na nagtatrabaho sa mga lugar ng edukasyon. Kabilang dito ang pagtuturo sa mga anak ng mga pangunahing manggagawa, pagtuturo sa mga batang nasa kustodiya, at pagbibigay ng edukasyon sa mga bilangguan. Nangangahulugan ito na inilalagay nila ang kanilang sarili sa panganib na mahawa ng Covid-19 araw-araw.

| “ | Ang ilan ay nasa bahay paminsan-minsan, ngunit marami sa kanila ay nasa lugar halos lahat ng oras na walang pahinga, nagtatrabaho sa masikip at mahinang bentilasyon na mga sitwasyon kung saan mahirap ang social distancing.

– NEU |

Nakasaad sa gabay ng gobyerno na dapat hatiin ang mga estudyante sa mga grupo (o 'mga bula') na may labindalawa, na mangangailangan sana ng paghahati ng mga klase sa tatlong grupo. Ipinaliwanag ng mga kinatawan kung paano binago ang gabay upang ang mga klase ay magkaroon na lamang ng labinlimang estudyante. Ang desisyong ito na lumipat sa mas malalaking grupo ay sumasalungat sa mas malawak na mga patakaran noong panahong iyon tungkol sa social distancing at paghahalo-halo, kabilang ang mga pagtitipon na limitado sa maximum na anim na tao. Ito ang naging dahilan upang mawalan ng tiwala ang mga kawani ng edukasyon sa gabay at mabigo dahil iniisip nilang nalalagay sila sa panganib. Gayundin, ang mga kawani ng sekondaryang paaralan ay madalas na nasa 'mga bula' na kinabibilangan ng mga pangkat ng buong taon.

| “ | Hindi praktikal ang gabay ng Kagawaran ng Edukasyon tungkol sa mga bula. Sasabihin sana ng agham na mas maliliit na bula, ngunit ang patakaran ay ibabalik ang lahat [sa mga sekondaryang paaralan]. Mayroon kang 200-300 sa isang bula at mga kawani na nagtatrabaho sa mga bula. Sa mga paaralang elementarya, mayroon kang mga bula sa klase, ngunit ito ay isang sistemang siksikan pa rin. Hindi ito makatuwiran. Hindi ito gumagana at hindi nito makontrol ang impeksyon.

– UNISON |

Inilarawan ng UNISON kung paano hindi pinapanatili ang mga 'bubbles' sa mga school bus dahil sa dami ng mga mag-aaral na sumasakay dito. May mga alalahanin noong panahong iyon tungkol sa kakulangan ng sapat na PPE para sa mga driver ng school bus at ang kawalan ng social distancing sa mga school bus, na nag-iwan sa mga driver ng bus na takot na mahawaan ng Covid-19.

Sinabi ng mga nasa sektor ng edukasyon na lalong mahirap ipatupad ang social distancing kapag nagtatrabaho kasama ang mga mas batang bata at sa mga paaralan ng SEND. Marami sa mga batang ito ang hindi nauunawaan ang konsepto ng social distancing, kaya imposible para sa mga kawani na sumunod sa gabay. Gayundin, binanggit ng UCU kung paano hindi isinasaalang-alang ng gabay sa social distancing para sa edukasyon ang mas mataas na panganib ng karahasan sa loob ng bilangguan at kung paano maaaring hindi praktikal ang social distancing para sa mga tagapagturo ng bilangguan. Iniulat din nila na hindi isinasaalang-alang ng gabay ang mga asignaturang bokasyonal na itinuturo sa mga paaralan, kolehiyo, at bilangguan, na nangangailangan ng malapit na pakikipag-ugnayan kapag nagtuturo.

| “ | Ang isang limang taong gulang na nagagalit o nangangailangan ng isang nakatatanda ay malamang na hindi susunod sa isang patakaran na nag-aatas sa kanila na magpanatili ng dalawang metrong distansya mula sa iba. Nagbibigay ito sa mga paaralan ng imposibleng gabay.

– NAHT |

Tumutok sa: mga libing, libing at kremasyon

Binigyang-diin ng mga nasa sektor ng libing, paglilibing, at kremasyon na mayroong malaking panganib na mahawaan ng Covid-19 ang mga kawani mula sa pakikisalamuha sa mga kasamahan at sa mga dumadalo sa mga seremonya. Itinuro ng kinatawan mula sa FBCA na sa ilang mga sementeryo at krematorya, kahit na may mga paghihigpit, ang mga kawani ay nakikisalamuha sa daan-daang tao bawat linggo. Ito ay inilarawan bilang lubhang nakakatakot para sa mga manggagawa at lumikha ng patuloy na mga alalahanin tungkol sa mga potensyal na antas ng pagkakalantad sa Covid-19.

Tumutok sa: pulisya at hustisya

Inilarawan ng POA kung gaano kahirap ipatupad ang social distancing sa mga bilangguan. Ito ay partikular na naging problematiko kung saan kinakailangan ang pisikal na pakikipag-ugnayan, kabilang ang kapag ang mga bilanggo ay nananakit sa sarili o nakikipag-away. Gayundin, ibinahagi ng kinatawan mula sa PCS kung paano naging hamon ang social distancing dahil sa layout ng mga gusali ng korte. Gayunpaman, ang ilang alternatibong paraan ng pagtatrabaho ay nakatulong upang mabawasan ang malapit na pakikipag-ugnayan, tulad ng pagdalo ng mga legal na propesyonal sa mga pagdinig sa korte nang malayuan.

Ibinahagi ng NPCC kung paano nagsimulang magtrabaho ang mga pulis sa magkakahiwalay na pangkat na hindi nagsasama-sama upang mabawasan ang pagkalat ng sakit sa mga manggagawa at komunidad.

| “ | Kung saan mo napagtanto na kakailanganin mong makipag-ugnayan sa mga mahihinang komunidad at mga taong nagpoprotekta…nangangahulugan ito [mga silo ng koponan] na maaari nilang [pulis] na magpatuloy sa pagtatrabaho sa loob ng kanilang trabaho nang hindi inilalagay sa panganib ang iba.”

– NPCC |

Tumutok sa: tingian

Sinasabing ang laki at uri ng espasyong pangtingian ay nagkaroon ng epekto sa kung paano maipapatupad ang mga hakbang sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho. Inilarawan ng USDAW kung paano ang mas maliliit na convenience store ay may mas kaunting espasyo para sa social distancing at kadalasang mas mahina ang bentilasyon kaysa sa mas malalaking tindahan at supermarket.

Binigyang-diin ng GMB Union na kahit na nagawang mapanatili ng mga kawani sa mga tindahan ang social distancing, hindi nasunod ang mga hakbang na iyon sa kantina ng mga kawani.

| “ | Nakalagay na ang lahat ng kontrol, naka-screen, may social distancing, may mga hand sanitizer, at nakasuot ng face mask ang mga tao, pero sa staff room, wala ni isa sa mga iyon ang nagamit. Gumagana nang maayos ang lahat ng kontrol sa shop floor, pero may impeksyon pa rin sa canteen at naroon ang lahat ng panganib ng kontaminasyon.”

– Unyon ng GMB |

Tumutok sa: transportasyon, pamamahagi at pag-iimbak

Sinabi ng USDAW na ang mga kompanya ng paghahatid ay nagsimulang maghatid ng mga test kit at PPE noong panahon ng pandemya, na kinasasangkutan ng mga drayber na malapit na nakipag-ugnayan sa mga indibidwal na posibleng nahawahan. Limitado ang gabay ng mga drayber ng paghahatid kung paano ligtas na maghatid ng mga item habang sinusunod ang mga hakbang sa social distancing, na lumikha ng kawalan ng katiyakan at pagkabalisa sa mga manggagawa.

| “ | Sobrang abala ang mga kompanya ng paghahatid ng parsela dahil nasa bahay ang mga tao… pero naghahatid din sila ng mga test kit sa mga taong posibleng may COVID… parang walang alam ang mga kasamahan nila.”

– USDAW |

Tumutok sa: sunog at pagsagip

Inilarawan ng FBU kung paano hindi isinasaalang-alang ng mga hakbang sa social distancing ang natatanging katangian ng pag-apula ng sunog at ang lapit na kailangan sa pagitan ng mga bumbero at mga kawani ng emergency control upang magampanan nang epektibo ang kanilang trabaho.

| “ | Sila [mga bumbero] ay nakaupo nang magkakalapit sa isang nakasarang espasyo. Ano ang hitsura ng social distancing sa banyo? Nasa shift kayo, kumakain nang magkakasama, nagsasanay nang magkakasama, at sama-samang pinapakilos. Ano ang hitsura ng social distancing sa isang bumbero? Mayroon kayong 5-6 na tao sa isang taksi. Hindi iyon 2 metro ang pagitan.”

– FBU |

Bentilasyon at iba pang mga hakbang sa pagkontrol

Binanggit ng mga kinatawan na habang tumataas ang kamalayan sa pagkalat ng Covid-19 sa pamamagitan ng hangin, nagkaroon din ng pagtaas ng pokus sa mga gabay sa bentilasyon. Tulad ng social distancing, mas mahirap itong ipatupad sa mas masisikip na mga espasyo tulad ng mga tindahan, silid-aralan, bilangguan, at mga lugar ng transportasyon kung saan hindi laging posible ang bentilasyon.

Tumutok sa: edukasyon

Maraming gusaling pang-edukasyon ang may mahinang bentilasyon dahil sa mga bintana na hindi mabuksan. Samakatuwid, ang mga nanatiling bukas ay hindi nakasunod sa gabay at nakapagbigay ng ligtas na kapaligiran na makakabawas sa pagkalat ng Covid-19. Kinailangang magpatuloy ang mga manggagawa sa pagtatrabaho sa mga espasyong walang sapat na bentilasyon, na lumilikha ng patuloy na mga alalahanin sa kaligtasan tungkol sa pagkalat ng virus sa hangin. Sa mga lugar ng edukasyon kung saan maaaring buksan ang mga bintana, sinabi ng mga kinatawan na sa panahon ng taglamig, ang mga silid ay masyadong malamig para sa mga manggagawa, bata, at kabataan, na lumilikha ng isang kapaligirang hindi angkop para sa pag-aaral.

| “ | Nang [ganap na muling nagbukas ang mga paaralan] noong taglamig ng 2021, napakababa ng temperatura kaya't iniulat ng mga miyembro ang mga bata at kawani na may mga namumulang kamay at labi dahil ang payo sa bentilasyon ay 'buksan ang mga bintana'. Nakabalot na para sa taglamig at nakikita ang sarili nilang hininga; hindi ito angkop na kapaligiran sa pag-aaral.

– NASUWT |

Itinampok ng mga nasa sektor ng edukasyon ang mga kasanayan na sa tingin nila ay nakatulong upang mapabuti ang pagkakapare-pareho ng kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho habang nagpapatuloy ang pandemya. Sinabi ng UCU na ang ilang mga employer ay nagsimulang magplano ng espasyo upang makamit ang naaangkop na antas ng bentilasyon, itinigil ang paggamit ng mga lugar na hindi maganda ang bentilasyon at naglagay ng air conditioning at HEPA filter.12, ngunit nadama nila na huli na itong naipatupad sa panahon ng pandemya. Naisip din ng mga kinatawan na ang mga monitor ng CO213 sa mga setting ng edukasyon ay huli na para magkaroon ng malaking epekto sa kaligtasan sa lugar ng trabaho, lalo na't walang mananagot sa pagtiyak na ang antas ng CO2 ay mananatiling ligtas, o para sa lumalaking alalahanin kung ito ay maging masyadong mataas. Iniulat din ng mga kawani ang kalituhan tungkol sa kung anong antas ng CO2 ang nakakatulong para sa isang ligtas na kapaligiran sa pag-aaral. Sa mga setting ng prison estate at mga youth offender, iniulat ng UCU na ang ilang mga gusali ay walang heater at ang mga tagapagturo sa bilangguan ay hinihiling na magturo sa wing kaysa magturo sa mga education block, na naglalagay sa kanila sa mas malaking panganib.

| “ | Malaki ang kakulangan ng pamumuhunan sa mga bilangguan at mga kolehiyo. Hindi mabuksan ang mga bintana, mahina ang bentilasyon, maliliit ang mga espasyo, ang ilan ay walang bintana. Ang ilan ay walang pampainit.”

– UCU |

| “ | Kalaunan, nang dumating ang mga CO2 monitor, isa na lang para sa bawat silid-aralan, pagkatapos ay isa na rin para sa bawat silid-aralan, ngunit nang mga panahong iyon ay nasa huling yugto na tayo ng pandemya – dapat ay mas maaga pa sana nangyari ang paglulunsad.”

– NEU |

Binigyang-diin ng mga kinatawan ang kahalagahan ng pagkakaroon ng presensya ng unyon at mga kinatawan ng kalusugan at kaligtasan upang makatulong na makamit ang mas ligtas na kapaligiran sa pagtatrabaho.

Tumutok sa: transportasyon, pamamahagi at pag-iimbak

Ang pagtatatag ng mga forum na partikular sa industriya, tulad ng Rail Industry Coronavirus Forum, ay itinuturing na mahalaga para sa pagpapalaganap ng mas malawak na kolaborasyon sa pagitan ng mga operator ng transportasyon at mga unyon. Nagbigay din ang mga ito ng plataporma para sa mga organisasyon na magkasundo sa mga ligtas na kondisyon at kasanayan sa pagtatrabaho.

Gumawa ng mga hakbang upang mabawasan ang mga panganib ng Covid-19 sa pamamagitan ng pagbabago sa mga tungkulin sa trabaho at mga kondisyon sa pagtatrabaho. Halimbawa, sa sektor ng transportasyon, inalis nila ang mga kawani ng tren sa pangongolekta ng pamasahe, staggered starting times, naglagay ng mga istasyon ng paghuhugas ng kamay, at nagsara ng mga kantina. Nagbigay ito sa mga manggagawa ng higit na katiyakan tungkol sa kanilang kapaligiran sa pagtatrabaho at nabawasan ang mga pangamba sa Covid-19.

Tumutok sa: tingian

Ang ilang teknolohikal na adaptasyon ay nagbigay ng mabisang proteksyon para sa mga manggagawa sa tingian. Binigyang-diin ng Bakers, Food and Allied Workers' Union (BFAWU) kung paano nakatulong ang pagtaas ng mga contactless payment system na maalis ang pangangailangan ng mga manggagawa na humawak ng pera mula sa mga customer. Gayunpaman, ang iba pang mga hakbang sa kaligtasan ay nagkaroon ng magkahalong resulta. Bagama't ipinatupad ang mga maskara at screen sa mga cash desk upang mapahusay ang kaligtasan ng mga manggagawa, binanggit ng GMB Union na madalas na nadarama ng mga customer na ang mga screen ay nangangahulugan na hindi na nila kailangang magsuot ng maskara, na nagpapataas ng mga panganib sa pagkalat para sa mga kawani.

Tumutok sa: mga libing, libing at kremasyon

Inilarawan ng mga nasa sektor ng libing, paglilibing, at kremasyon ang positibong epekto ng mga serbisyo sa digital na pagpaparehistro ng kamatayan. Itinampok nila kung paano naging epektibo ang kakayahang magparehistro ng mga pagkamatay at magsumite ng mga dokumento online, at nagpahayag ng pag-asa na ang mga digital na kakayahan na ito ay patuloy na magagamit.

| “ | Isang bagay na naging epektibo – ang kakayahang magrehistro ng kamatayan online. Sana ay bumalik [ito]. Ang kakayahang magsumite ng mga bagay nang digital ay naging epektibo nang husto.”

– ICCM |

Nabanggit ng NBC na lubos na pinahahalagahan ng mga komunidad ng mga Hudyo at Muslim ang bilis ng pagproseso ng mga papeles. Ang kakayahang pamahalaan ang dokumentasyon nang digital ay nagbigay-daan sa mga pamilya na maisagawa ang mga libing nang agaran, alinsunod sa mga kinakailangan sa relihiyon.

| “ | Labis ang pasasalamat ng mga komunidad ng mga Hudyo at Muslim sa kung gaano kabilis nila inasikaso ang mga papeles. [Ito] ay nagbigay-daan sa amin upang mabilis na mailibing ang aming mga mahal sa buhay, dahil nagawa naming pangasiwaan ang mga bagay-bagay nang digital.

– NBC |

Tumutok sa: pulisya at hustisya

Ipinaliwanag ng UNISON at ng NPCC na ang mga pagtatasa ng panganib na isinagawa sa mga serbisyo ng pulisya at probasyon ay nagsiwalat ng hindi proporsyonal na panganib ng Covid-19 na magdulot ng malubhang sakit para sa mga manggagawang may etnikong minorya, lalo na sa mga may lahing Itim at Asyano. Ang mga pagtatasa na ito ay humantong sa mga iniakmang hakbang sa suporta para sa mga kawaning may lahing minorya, kabilang ang mga kaayusan sa malayuang pagtatrabaho at mga kahilingan sa pagsasanggalang para sa mga nahaharap sa hindi proporsyonal na panganib ng Covid-19.

| “ | Para sa aming mga miyembro na nagmula sa mga komunidad [ng etnikong minorya], mayroong dagdag na stress sa pagkaalam na ang mga miyembro ng kanilang sariling mga komunidad ay hindi proporsyonal na naaapektuhan at mas maraming namamatay.

– UNISON |

Epekto sa pisikal na kalusugan, kalusugang pangkaisipan, at kagalingan ng mga pangunahing manggagawa