Mga Pasasalamat

Nais naming pasalamatan ang lahat ng mga bata at kabataan na nakibahagi sa pananaliksik na ito, at sa mga tumulong upang suportahan ang kanilang pakikilahok. Espesyal na pasasalamat din sa Acumen Fieldwork, The Mix, The Exchange at ang Core Participants. Salamat sa Save the Children, Coram Voice, YoungMinds, Alliance for Youth Justice, UK Youth, PIMS-Hub, Long Covid Kids, Clinically Vulnerable Families, Article 39, Leaders Unlocked at Just for Kids Law, kasama ang Children's Rights Alliance para sa England, para sa iyong tulong sa panahon ng pagpaplano at recruitment para sa pananaliksik na ito. Sa forum ng Mga Bata at Kabataan: talagang pinahahalagahan namin ang iyong mga pananaw, suporta at hamon sa aming trabaho. Ang iyong input ay talagang nakatulong sa paghubog sa ulat na ito.

Ang ulat ng pananaliksik na ito ay inihanda sa kahilingan ng Tagapangulo ng Inquiry. Ang mga pananaw na ipinahayag ay sa mga may-akda lamang. Ang mga natuklasan sa pananaliksik na nagmumula sa fieldwork ay hindi bumubuo ng mga pormal na rekomendasyon ng Tagapangulo ng Inquiry at hiwalay sa legal na ebidensya na nakuha sa mga pagsisiyasat at pagdinig.

1. Panimula

1.1 Background sa pananaliksik

Ang UK Covid-19 Inquiry (“the Inquiry”) ay nai-set up upang suriin ang tugon at epekto ng UK sa Covid-19 pandemic, at matuto ng mga aral para sa hinaharap. Ang gawain ng Pagtatanong ay ginagabayan nito Mga Tuntunin ng Sanggunian. Ang mga pagsisiyasat ng Inquiry ay isinaayos sa mga module. Modyul 8 susuriin ang epekto ng pandemya sa mga bata at kabataan.

Inatasan ng UK Covid-19 Inquiry si Verian na isagawa ang programang ito ng pananaliksik upang magbigay ng larawan ng mga karanasan ng mga bata at kabataan, at kung paano nila nadama ang epekto ng UK Covid-19 pandemic (“ang pandemya”) sa kanila. Ang mga natuklasan ng ulat na ito ay gagamitin ng Inquiry upang maunawaan kung paano naramdaman at naranasan ng mga bata at kabataan ang mga pagbabagong naganap sa pandemya at ang mga epekto nito. Ang ulat ng pananaliksik na ito ay hindi idinisenyo upang magpakita ng ebidensya kung paano nagbago ang mga partikular na serbisyo sa panahong ito. Ang mga bahagi ng karanasan ng mga bata at kabataan na ginalugad sa pamamagitan ng pananaliksik na ito ay tinukoy ng isang hanay ng mga katanungan sa pananaliksik, na nakabalangkas sa Appendix A.

1.2 Diskarte sa pananaliksik

Ang paraan ng pagsasaliksik para sa programang ito ay mga malalim na panayam.¹ Nagsagawa si Verian ng 600 panayam sa mga bata at kabataan sa pagitan ng edad na 9 at 22 (na samakatuwid ay nasa pagitan ng edad na 5 at 18 sa panahon ng pandemya) sa UK. Bago at sa panahon ng pakikipanayam, nagtipon din si Verian ng mga sangguniang grupo ng mga bata at kabataan upang ipaalam ang disenyo ng mga gabay sa pakikipanayam, mga materyales ng kalahok at mga bersyon ng mga natuklasang pambata. Bilang karagdagan, ang mga talakayan ng focus group ay isinagawa kasama ang mga magulang at guro bago ang mga panayam upang gabayan ang disenyo ng mga materyales sa pananaliksik.

Ang mga panayam ay kumuha ng trauma-informed approach upang matiyak na ang pakikilahok ay hindi sinasadyang magdulot ng muling pagka-trauma o pagkabalisa. Ang mga batang may edad na 9-12 ay may magulang o tagapag-alaga na naroroon sa mga panayam, habang ang mga nasa edad 13+ ay maaaring pumili na magkaroon ng opsyong ito kung kailangan nila. Ang bawat bata at kabataang nakapanayam ay inanyayahan na kumpletuhin ang isang maikling opsyonal na survey ng feedback pagkatapos ng kanilang pakikipanayam tungkol sa kanilang karanasan. Higit pang impormasyon sa paraan ng pagsasaliksik, kabilang ang mga kasosyong sumusuporta sa trabaho ni Verian, ay nasa Appendix B.

- ¹Ang mga depth interview ay isang qualitative research technique na tumutukoy sa pagsasagawa ng mga detalyadong talakayan sa maliit na bilang ng mga kalahok sa isang format ng pakikipag-usap. Pangunahing bukas ang mga tanong sa panayam upang payagan ang mga insight na natural na lumabas kaysa sa pagsunod sa isang mahigpit na plano.

1.3 Sampol ng pananaliksik

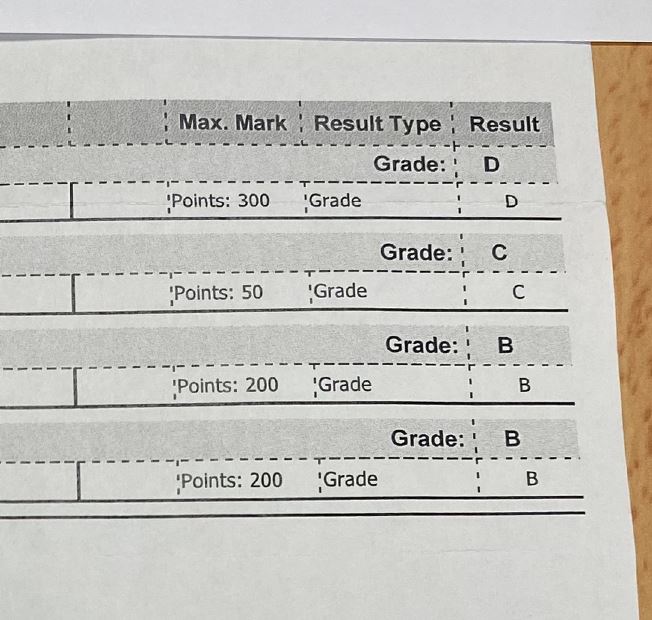

Ang 600 na panayam na isinagawa ni Verian ay binubuo ng 300 mga panayam sa isang 'pangkalahatan' na sample ng mga kalahok na malawak na sumasalamin sa populasyon ng UK, at 300 na may isang 'naka-target' na sample ng mga partikular na grupo na pinili batay sa ebidensya na sila ay partikular na negatibong naapektuhan ng pandemya. Dapat pansinin na ang ilang mga bata at kabataan ay nakamit ang pamantayan sa paglahok para sa higit sa isa sa mga grupong ito (tingnan ang Larawan 1 sa ibaba). Halimbawa, ang karamihan sa mga naghahanap ng asylum ay nasa pansamantala o masikip na tirahan. Karamihan sa mga nakipag-ugnayan sa sistema ng hustisyang kriminal ay nakipag-ugnayan din sa mga serbisyo sa kalusugan ng isip at pangangalaga sa lipunan ng mga bata.

Figure 1: Mag-overlap sa pagitan ng mga pangkat sa target na sample

1.4 Saklaw ng ulat na ito

Itinatakda ng ulat na ito ang mga natuklasan mula sa malalalim na panayam sa programang pananaliksik ng Mga Bata at Mga Boses ng Kabataan. Ang mga natuklasang ito ay idinisenyo upang tulungan ang Pagtatanong na maunawaan kung ano ang naramdaman ng mga bata at kabataan tungkol sa, at naranasan, ang mga pagbabagong naganap sa panahon ng pandemyang ito. Tutulungan din nila ang pagtukoy sa mga pangunahing lugar para sa karagdagang pagsusuri at pagsasaalang-alang at pagsuporta sa Inquiry sa pagtugon nito Mga Tuntunin ng Sanggunian.

Nagsisimula ang ulat sa pamamagitan ng pagtalakay sa mga pangunahing salik na tinukoy bilang paghubog sa mga karanasan ng mga bata at kabataan sa panahon ng pandemya. Kasunod nito, ang ulat ay bumaling sa isang detalyadong paggalugad ng mga karanasang ibinahagi ng mga bata at kabataan, simula sa mga pagbabago sa kanilang kapaligiran sa tahanan at mga relasyon sa pamilya sa panahong ito, bago lumipat sa mga epekto ng pandemya sa iba pang aspeto ng kanilang buhay, kabilang ang edukasyon, online na pag-uugali, kalusugan at kagalingan. Ang ikalawang kalahati ng ulat ay nakatuon sa mga karanasan ng mga partikular na setting at serbisyo sa panahon ng pandemya.

Ito ay hindi isang ulat ng Tagapangulo ng Pagtatanong at ang mga natuklasan nito ay hindi bumubuo ng mga natuklasan ng Tagapangulo. Ang interpretasyon ng mga natuklasan at talakayan ng mga implikasyon ay yaong sa koponan ng pananaliksik ng Verian.

Ang Bawat Story Matters ay isang hiwalay na pagsasanay sa pakikinig na ginagawa ng Inquiry. Kinukuha ng tala ng Every Story Matters ang mga karanasan ng mga bata at kabataan sa pamamagitan ng lens ng mga nasa hustong gulang sa kanilang buhay na nagbigay ng pangangalaga o suporta. Nag-ambag din ang mga kabataang higit sa 18 sa talaan ng Every Story Matters. Mahalagang tandaan na ang mga pananaw ng mga nasa hustong gulang tungkol sa mga karanasan ng mga bata at kabataan ay maaaring magkaiba sa mga lugar mula sa mga natuklasan ng ulat na ito.

1.5 Gabay para sa mga mambabasa

Mga halaga at limitasyon ng kwalitatibong pananaliksik

Isang husay na diskarte ang pinagtibay para sa pag-aaral na ito upang magbigay ng malalim na pananaw sa buhay na karanasan ng mga bata at kabataan sa panahon ng pandemya at upang bigyang-buhay ang kanilang mga boses. Ang kwalitatibong pananaliksik ay mainam para sa pagsisiyasat sa pagkakaiba ng mga karanasan; binibigyan nito ng pagkakataon ang mga kalahok na ibahagi ang kanilang mga karanasan nang detalyado at espasyo upang pagnilayan ang kanilang mga motibasyon at emosyon. Ang mga pamamaraan ng husay ay mahalaga kapag nag-e-explore ng mga kumplikadong social phenomena at idinisenyo upang ilarawan at bigyang-kahulugan ang mga ito nang malalim, na nagbibigay ng yaman ng detalye.

Ang mga pamamaraan ng husay ay hindi idinisenyo upang sukatin ang dalas o pagkalat ng isang karanasan o asosasyon. Bilang karagdagan, ang mga qualitative sample ay idinisenyo nang may layunin upang makuha ang mga karanasan ng mga partikular na grupo, na may detalyadong pamantayan sa recruitment para sa mga kalahok. Dahil ang naturang kwalitatibong pananaliksik ay hindi idinisenyo upang maghatid ng mga natuklasang kinatawan ng istatistika at hindi makapagbibigay ng parehong antas ng paglalahat gaya ng dami ng data. Alinsunod dito, kapag ang mga terminong gaya ng 'ilan' ay ginagamit kapag nag-uulat ng husay na pananaliksik, ang mga ito ay hindi nakatali sa isang partikular na halaga ng numero. Dapat ding tandaan na ang mga partikular na halimbawa ng mga indibidwal na karanasan ay maaaring hindi kinatawan. Gayunpaman, maaaring gamitin ang qualitative research upang mag-alok ng insight sa isang spectrum ng mga karanasan at pananaw ng tao sa paraang hindi magagawa ng quantitative na pamamaraan.

Ang qualitative research ay isa ring makapangyarihang tool kapag triangulated gamit ang quantitative data at iba pang anyo ng ebidensya. Hindi isinasagawa ng ulat na ito ang triangulation na ito. Gayunpaman, ang karagdagang triangulation ng mga natuklasan nito ay maaaring maging partikular na kapaki-pakinabang sa pagbibigay ng konteksto sa spectrum ng mga karanasang inilarawan nang may husay kung saan mayroong sumusuportang data o ebidensya sa pagkalat ng mga ito.

Isang tala sa terminolohiya

Ang terminong 'mga bata at kabataan' ay ginagamit sa buong ulat na ito upang sama-samang sumangguni sa mga nakapanayam para sa pananaliksik na ito. Gayunpaman, kung saan nauugnay, ginagamit namin ang mga terminong 'mga bata' o 'bata' para tumukoy sa mga mas bata sa 18 noong kapanayamin. Ginagamit namin ang mga terminong 'kabataan' o 'kabataan' para tumukoy sa mga 18 taong gulang o mas matanda kapag iniinterbyu. Ang mga sanggunian sa mga magulang ay dapat na maunawaan na kasama rin ang mga tagapag-alaga at tagapag-alaga. Ang mga quote mula sa mga bata at kabataan ay kinabibilangan ng kanilang edad sa punto ng pakikipanayam, at sa ilang partikular na mga kaso (para sa mga may espesyal na pangangailangang pang-edukasyon at sa mga partikular na setting sa panahon ng pandemya) ay nagpapahiwatig ng mahalagang impormasyon sa konteksto tungkol sa kanilang mga kalagayan upang makatulong na mas maunawaan ang kanilang tugon. Dahil hindi hiniling sa mga kalahok na ibigay ang kanilang petsa ng kapanganakan, hindi posible na palagiang tukuyin ang mga edad hanggang Marso 2020. Bukod dito, dahil ang ilan sa mga karanasang inilarawan sa mga taon, ang pagkonekta sa mga account na ito sa kanilang edad sa simula ng pandemya ay maaaring mapanlinlang. Partikular na tinanong ni Verian ang mga bata at kabataan tungkol sa kanilang mga karanasan mula 2020-22, kaya ginagamit ng ulat ang past tense. Gayunpaman, mahalagang tandaan na para sa ilan sa mga kabataang nakausap namin, ang kanilang mga kondisyon at ang epekto ng Covid-19 ay nagpapatuloy hanggang sa kasalukuyan.

Babala sa nilalaman

Ang ilan sa mga kuwento at tema na kasama sa talaang ito ay kinabibilangan ng mga paglalarawan ng kamatayan, mga karanasan sa malapit sa kamatayan, pang-aabuso, sekswal na pag-atake at makabuluhang pisikal at sikolohikal na pinsala. Ang mga ito ay maaaring nakababahala. Kung gayon, hinihikayat ang mga mambabasa na humingi ng tulong mula sa mga kasamahan, kaibigan, pamilya, grupo ng suporta o mga propesyonal sa pangangalagang pangkalusugan kung kinakailangan. Isang listahan ng mga serbisyong sumusuporta ay ibinigay din sa UK Covid-19 Inquiry website.

2. Mga salik na humubog sa karanasan sa pandemya

Ipinakikilala ng seksyong ito ang mga salik na naging partikular na naging hamon ng pandemya para sa ilang bata at kabataan, at ang mga salik na nagpoprotekta at nagpapagaan na tumulong sa ilang bata at kabataan na makayanan at umunlad pa nga.

Sa mga panayam, hindi pangkaraniwan na puro positibo o negatibo ang mga ulat ng mga bata at kabataan tungkol sa pandemya. Iniugnay ng ilan ang pandemya sa magkahalong damdamin - halimbawa, maaari nilang ilarawan ang pakiramdam na medyo masaya at malaya sa hindi pagpasok sa paaralan sa simula, ngunit kalaunan ay nakakaramdam ng pagkabigo at paghihiwalay. Inilarawan ng ilang mga bata at kabataan ang mga hamon na kanilang kinaharap sa panahon ng pandemya, ngunit nadama din na may mga positibong aspeto sa karanasan o kahit na mga bagay na nakatulong sa kanila na makayanan. Dahil dito, nakuha ng pananaliksik na ito ang isang malawak na pagkakaiba-iba ng mga karanasan at ang spectrum ng pagtugon na ito ay makikita sa buong ulat na ito.

Batay dito, tinutukoy ng aming pagsusuri ang ilang salik na nagpahirap sa pandemya para sa ilan gayundin ang mga salik na tumulong sa mga bata at kabataan na makayanan sa panahong ito.

Larawan 2: Mga salik na humubog sa mga karanasan sa pandemya

| Mga salik na nagpahirap sa pandemya para sa mga bata at kabataan | Mga salik na nakatulong sa mga bata at kabataan upang makayanan at umunlad |

|---|---|

| Tensyon sa bahay | Mga sumusuportang relasyon |

| Ang bigat ng responsibilidad | Paghahanap ng mga paraan upang suportahan ang kagalingan |

| Kakulangan ng mga mapagkukunan | Gumagawa ng isang bagay na kapakipakinabang |

| Tumaas na takot | Kakayahang magpatuloy sa pag-aaral |

| Pinataas na mga paghihigpit | |

| Pagkagambala sa suporta | |

| Nakakaranas ng pangungulila |

Ang ilan sa mga nakapanayam ay naapektuhan ng kumbinasyon ng mga negatibong salik na nakalista sa itaas, partikular ang mga na-recruit para sa target na sample at ang mga nakamit ang pamantayan sa paglahok para sa higit sa isa sa mga target na grupo. Sa ilang mga kaso, ang kanilang karanasan sa pandemya ay napaka-negatibo at ang pagkakaroon ng mga suportang ugnayan na magagamit at mga paraan upang pangalagaan ang kanilang sariling kapakanan ay partikular na mahalaga.

Sa ibaba ay tinutuklasan namin nang mas detalyado ang mga salik na humubog sa mga karanasan ng pandemya para sa mga bata at kabataan. Isinama namin ang mga case study sa kabuuan upang ilarawan ang mga ito. Kinuha ang mga ito mula sa mga indibidwal na account, na binago ang mga pangalan.

Mga salik na naging dahilan upang maging mahirap ang pandemya

Ibinabalangkas namin sa ibaba ang mga salik na naging dahilan upang maging mahirap ang pandemya para sa ilang mga bata at kabataan. Sa ilang mga kaso, ang pagiging apektado ng kumbinasyon ng mga salik na ito ay nagpalala sa epekto ng pandemya para sa mga bata at kabataan na nakaranas ng maraming hamon nang sabay-sabay. Ang mga paghihirap na kanilang kinaharap ay maaari ding madagdagan ng pakikipag-ugnayan ng mga salik na ito, tulad ng pagkagambala sa suporta kapag nakakaranas ng bago o mas maraming hamon sa tahanan.

Maaaring maranasan ng mga bata at kabataan sa iba't ibang sitwasyon ang mga hamon na ginalugad sa ibaba, bagama't ang kakulangan ng mga mapagkukunan ay partikular na nakaapekto sa mga nasa mababang sambahayan. Dapat tandaan na ang ilan sa mga salik na ito ay malinaw na nauugnay sa mga partikular na pangyayari na tinukoy sa recruitment - halimbawa, na naapektuhan ng parehong tumaas na mga paghihigpit at tumaas na takot dahil sa pagiging nasa isang clinically vulnerable na pamilya. Sa ilang mga kaso, natugunan ng mga nakapanayam ang pamantayan para sa dalawa o higit pang mga naka-target na grupo at bilang resulta ay nahaharap sa maraming hamon sa panahon ng pandemya, halimbawa, pagkakaroon ng parehong mga responsibilidad sa pangangalaga at pagprotekta, o pakikipag-ugnayan sa parehong mga serbisyo sa kalusugan ng isip at pangangalaga sa lipunan ng mga bata.

Tensyon sa bahay: ang pag-igting sa bahay ay nagpahirap sa pandemya para sa ilang mga bata at kabataan. Sa ilang mga kaso, ito ay nauna pa sa pandemya at pinalala ng lockdown, habang sa ilang mga kaso ay lumitaw ang mga tensyon kapag ang lahat ay natigil sa bahay nang sama-sama, lalo na kung saan ang lugar ng tirahan ay masikip. Inilarawan ng mga bata at kabataan ang epekto ng pakikipagtalo o pakiramdam na hindi komportable sa kanilang mga kapatid o magulang o nasaksihan ang tensyon sa pagitan ng mga nasa hustong gulang sa sambahayan. Ang mga pag-igting na ito ay nangangahulugan na para sa ilan, ang tahanan ay hindi palaging nararanasan bilang isang ligtas o sumusuportang lugar sa panahon ng pandemya, na isang mahalagang salik upang makayanan ang lockdown.

| Pakiramdam na nakulong sa pamilya

Inilarawan ni Alex, na may edad na 21, kung gaano kahirap para sa kanyang pamilya na natigil sa bahay nang magkasama kapag ang lahat ay nakasanayan na magkaroon ng ilang kalayaan at espasyo. Nasira ang mga relasyon sa panahon ng tindi ng lockdown. “Mas nakaka-stress dahil lahat kami ay nasa iisang bubong dalawampu't apat na oras sa isang araw, kumpara sa, alam mo, ako at ang aking kapatid na babae ay aalis, ako ay papasok sa kolehiyo, siya ay papasok sa paaralan... na nagkakamabutihan... Hindi ito ang gusto namin noong panahong iyon, kailangan naming gumugol ng oras na magkasama... ang nanay at tatay ko sa iisang bahay... marahil ay hindi maganda sa aking mga magulang, dalawampu't apat sa kanilang mga magulang, alinman sa dalawampu't apat sa aking mga magulang. at ako at ang aking kapatid na babae ay malamang na hindi naging maayos.” Pagkasira ng kasal sa panahon ng pandemya Inilarawan ni Sam, na may edad na 16, ang pagsaksi sa pagkasira ng kasal ng kanyang mga magulang sa panahon ng pandemya. Nahirapan ang kanyang ina sa kanyang mental health pagkatapos nito at nalaman ni Sam na lahat ng nangyayari sa bahay ay nakaapekto sa kanyang sariling kapakanan at mga relasyon, dahil mas lumayo siya sa mga kaibigan. “Sa palagay ko [ang pandemya] ay marahil, tulad ng, isa sa mga pangunahing dahilan kung bakit naghiwalay ang aking mga magulang... Sa tingin ko kailangan lang nilang gumugol ng mas maraming oras sa isa't isa at sa palagay ko napagtanto nilang pareho na hindi iyon ang pinakamagandang ideya... Marami pa silang pinagtatalunan ngunit medyo nagtalo pa rin sila... Kung hindi nangyari ang Covid, hindi ko akalain na magdiborsyo sila... at pagkatapos ay iisipin ko ang aking mga problema sa kalusugan ng isip. mga kaibigan], parang, naging mas malapit sa kanilang pamilya... hindi ako masyado.” |

Ang bigat ng responsibilidad: Ang ilang mga bata at kabataan ay umako ng mga responsibilidad sa bahay sa panahon ng pandemya. Pati na rin ang pagdadala ng mga praktikal na gawain na kailangang gawin, tulad ng pag-aalaga sa isang taong may sakit, pag-aalaga sa mga kapatid, o pag-sanitize sa pamimili para sa isang taong may clinically vulnerable, naramdaman din ng ilan ang emosyonal na bigat ng pagsuporta sa kanilang pamilya sa panahong ito, lalo na kung saan ang mga tao sa labas ng sambahayan ay hindi maaaring pumunta at tumulong. Ang ilan ay naapektuhan din ng kamalayan sa mga paghihirap na pinagdadaanan ng mga nasa hustong gulang, kabilang ang lumalalang kalusugan ng isip, mga alalahanin tungkol sa pananalapi at mga karanasan sa pangungulila. Ang pagkakalantad na ito sa responsibilidad at stress ng mga nasa hustong gulang ay nangangahulugan na ang ilang mga bata at kabataan ay "mabilis na lumaki" sa panahon ng pandemya.

| Walang pagtakas sa mga responsibilidad sa pangangalaga

Inilarawan ni Robin, na may edad na 18, ang mga hamon ng pag-aalaga sa kanyang ina, isang solong magulang, sa panahon ng pandemya. Bilang nag-iisang anak ay nakasanayan na niyang gampanan ang responsibilidad na ito ngunit sa karaniwang panahon ay binibigyan siya ng paaralan ng kaunting pahinga mula sa kanyang mga responsibilidad sa tahanan. Ang pagiging stuck sa bahay sa panahon ng lockdown ay naging mas mahirap para sa kanya na makayanan, at nangangahulugan din na lumala ang kalusugan ng isip ng kanyang ina. Inilarawan niya ang pagiging "nawalan ng emosyon" at nahihirapan sa bigat ng responsibilidad. "Pakiramdam ko, kung wala kang magandang buhay sa bahay, ang paaralan ay isang malaking tagapagligtas para sa iyo dahil nangangahulugan ito na wala ka sa kapaligiran na iyon sa buong araw at makikita mo ang iyong mga kaibigan habang nandoon ka... Ako ay nalulumbay dahil wala akong pahinga mula sa aking sitwasyon sa tahanan. At parang napakaraming responsibilidad sa aking mga balikat sa lahat ng oras... at parang, sa kabila noon, ang ganda noon, sa paaralan. was gone it was such a big hit because that was my way of coping... It made it harder to deal with my mom at home... it was like a huge emotional workload and I just usually have the ability to deal with it and cope with it pero hindi kapag natigil ka doon sa lahat ng oras." Nalantad sa stress ng matatanda Si Riley, may edad na 22, ay nakatira sa bahay noong panahon ng pandemya kasama ang kanilang mga magulang. Ito ay isang mahirap na oras para sa pamilya dahil ang kanilang ina ay clinically vulnerable at ang kanilang kapatid, na lumipat, ay nahihirapan sa isang adiksyon. Ang pamumuhay sa ganoong kalapit na lugar sa panahon ng lockdown – “parang nasa pressure cooker ka” – ang naglantad sa kanila sa stress na pinagdadaanan ng kanilang mga magulang at inilarawan nila na nagsimulang makibahagi dito kaysa sa pakiramdam na parang bata pa. "Lahat ay nakaramdam ng matinding kaba. Kaya't may ganoong klaseng grupo na nag-aalala... Parang kailangan kong makita [ang aking mga magulang], tulad ng, higit pa bilang mga tao kaysa lamang, tulad ng, 'oh my mom's always nagging at me to do this'... Dahil, parang nakikita ko siya, parang, sa lahat ng oras... sa, parang, medyo vulnerable na paraan dahil sa, parang., parang na-stress ang mga magulang ko sa lahat, parang na-stress ako sa lahat. isang matanda.” |

Kakulangan ng mga mapagkukunan: Ang kakulangan ng panlabas na mapagkukunan ay naging dahilan upang mas mahirap makayanan ang pandemya para sa ilang mga bata at kabataan mula sa mga pamilyang may limitadong mapagkukunang pinansyal. Ang paninirahan sa masikip na tirahan ay lumikha ng tensyon mula sa pakiramdam na "nasa ibabaw ng isa't isa" at naging mas mahirap na makayanan ang Covid-19 sa sambahayan o protektahan ang mga miyembro ng pamilya na may mga klinikal na bulnerable, gayundin ang pagpapahirap sa paghahanap ng espasyo para gawin ang mga gawain sa paaralan. Ang hindi pagkakaroon ng pare-parehong access sa mga device o isang maaasahang koneksyon sa internet ay nagpahirap din sa pag-aaral sa bahay, gayundin sa paglimita sa mga pagkakataong kumonekta sa iba, mag-relax o matuto ng mga bagong bagay online. Bagama't hindi ito itinaas ng mga bata at kabataang walang espasyo sa labas bilang isang isyu, ang mga may hardin ay naglarawan ng mga paraan upang palakasin ang kagalingan at magsaya na hindi mararanasan ng mga walang hardin.

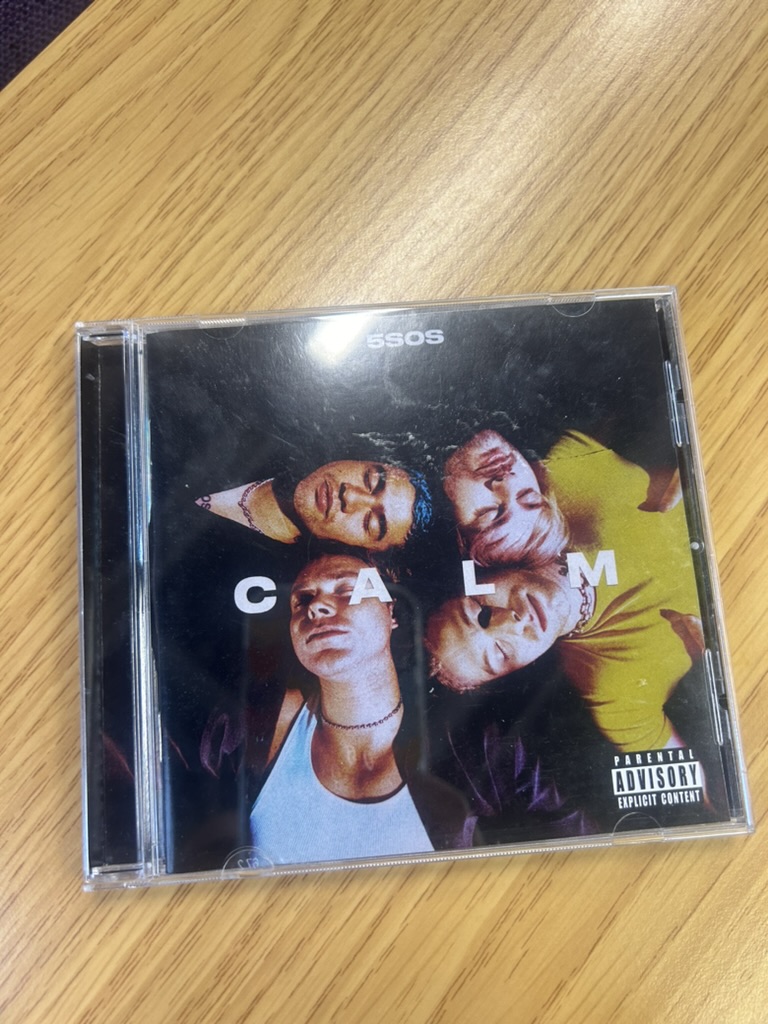

| Mga pakikibaka sa online na pag-aaral

Si Jess, na may edad na 15, ay nahirapan na makasabay sa pag-aaral sa bahay sa panahon ng pandemya. Ibinahagi niya ang isang lumang computer sa kanyang kapatid at mayroon talagang pasulput-sulpot na Wi-Fi, na nagdulot ng kakila-kilabot na buffering sa mga online na lesson at nangangahulugan na hindi siya makakasali nang maayos. Nagdala siya ng larawan² ng kanyang sarili na nakaupo sa computer dahil ito ay isang napakalakas na alaala ng pandemya para sa kanya: "[Dinala ko ang larawang ito sa panayam] dahil sa mga paghihirap sa pagiging online. Malinaw, tulad ng, ang lagging, ang Wi-Fi ay baliw... [Kami ng aking kapatid na lalaki] ay nagkaroon ng isang nakabahaging computer. Ang paaralan ay hindi nagbigay sa amin ng kahit ano ... ito ay, tulad ng, glitching nang husto, at pagkatapos ay ang Wi-Fi ay napakasama dahil ang Wi-Fi ay napakasama. ay hindi maganda... Ano, tulad ng, maaari naming ipatupad upang, tulad ng, bawasan ang pinsala?… Magbigay ng mga computer at mas mahusay na koneksyon sa internet. Walang puwang para magtrabaho Natagpuan ni Cam, na may edad na 15, ang lockdown na "medyo" nakatira sa isang flat kasama ang kanyang mga magulang at dalawang kapatid, na kasama niya sa isang silid-tulugan. Sanay siya na medyo masikip minsan, ngunit hindi sanay sa mga hamon ng pagsisikap na gawin ang pag-aaral sa bahay sa isang maliit na espasyo, na talagang nakakalito: "Lalo na dahil iisa lang ang mesa namin, parang isang magandang mesa. Kaya napakahirap magbalanse kung sino ang maaaring magkaroon ng mesa at kung sino ang maaaring pumunta sa sahig at magtrabaho. Dahil minsan hindi mo kailangan ang mesa. Ito ay parang isang matigas na dibuhista sa sahig." |

- ² Ang mga bata at kabataan na nakikibahagi sa mga panayam ay hiniling na magdala ng isang bagay, larawan o larawan na nagpapaalala sa kanila ng pandemya, kung komportable silang gawin ito. Pagkatapos ay ibinahagi nila ito nang maaga sa panayam at ipinaliwanag kung bakit nila ito pinili.

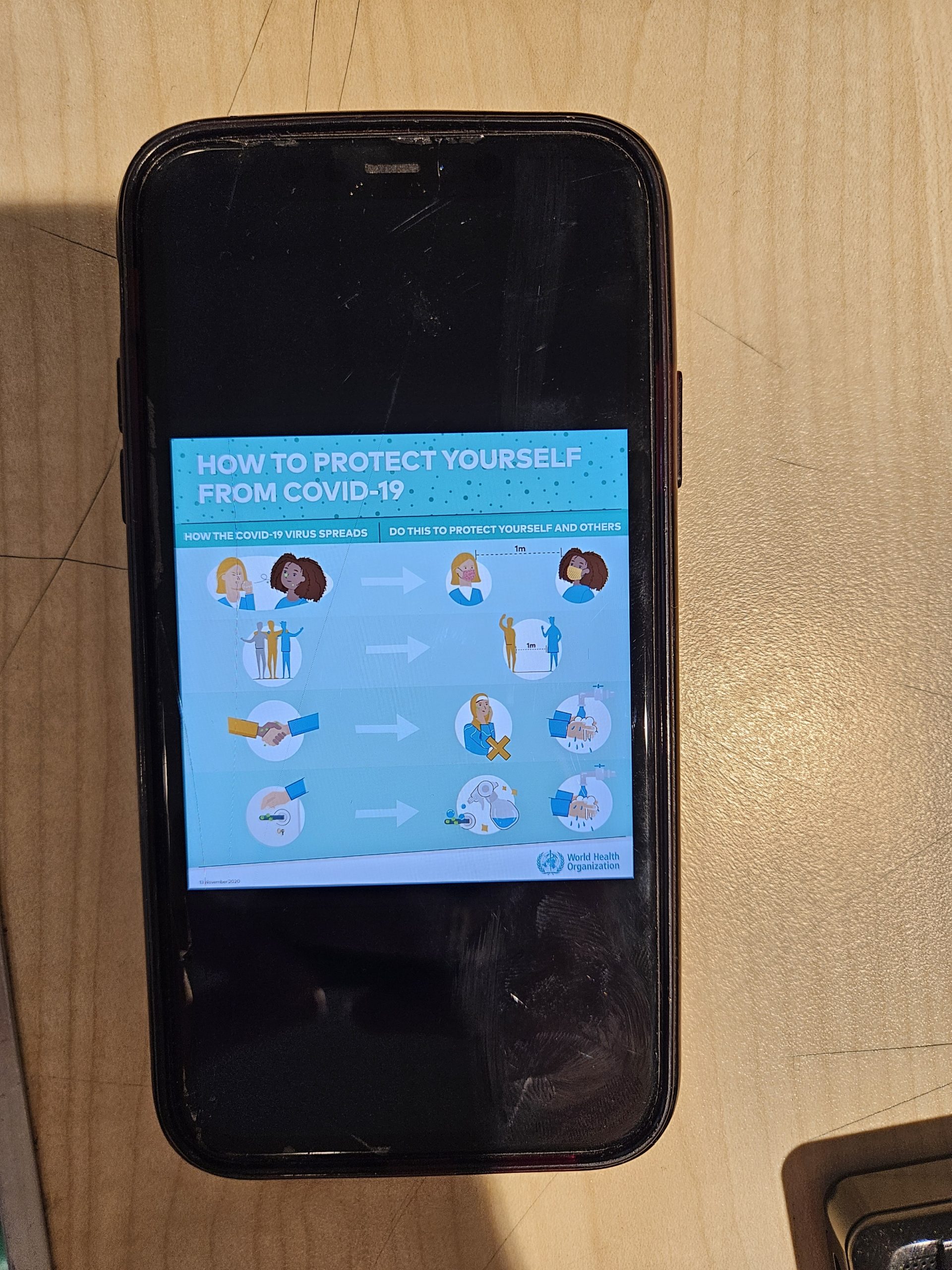

Tumaas na takot: Ang mga bata at kabataang may kapansanan sa katawan at ang mga may kondisyon sa kalusugan, o sa mga pamilyang madaling maapektuhan ng klinikal, ay inilarawan ang kanilang mga damdamin ng kawalan ng katiyakan, takot at pagkabalisa tungkol sa panganib na mahuli ang Covid-19 at ang malubha - at sa ilang mga kaso na nagbabanta sa buhay - mga implikasyon na maaaring magkaroon nito para sa kanila o sa kanilang mga mahal sa buhay. Ang mga bata at kabataan sa mga secure na setting ay nadama din na mahina at natatakot na mahuli ang Covid-19 kapag nagbabahagi ng mga karaniwang espasyo sa ibang tao sa panahon ng pandemya. Ang pagdanas ng pangungulila sa panahon ng pandemya ay maaari ring humantong sa matinding takot.

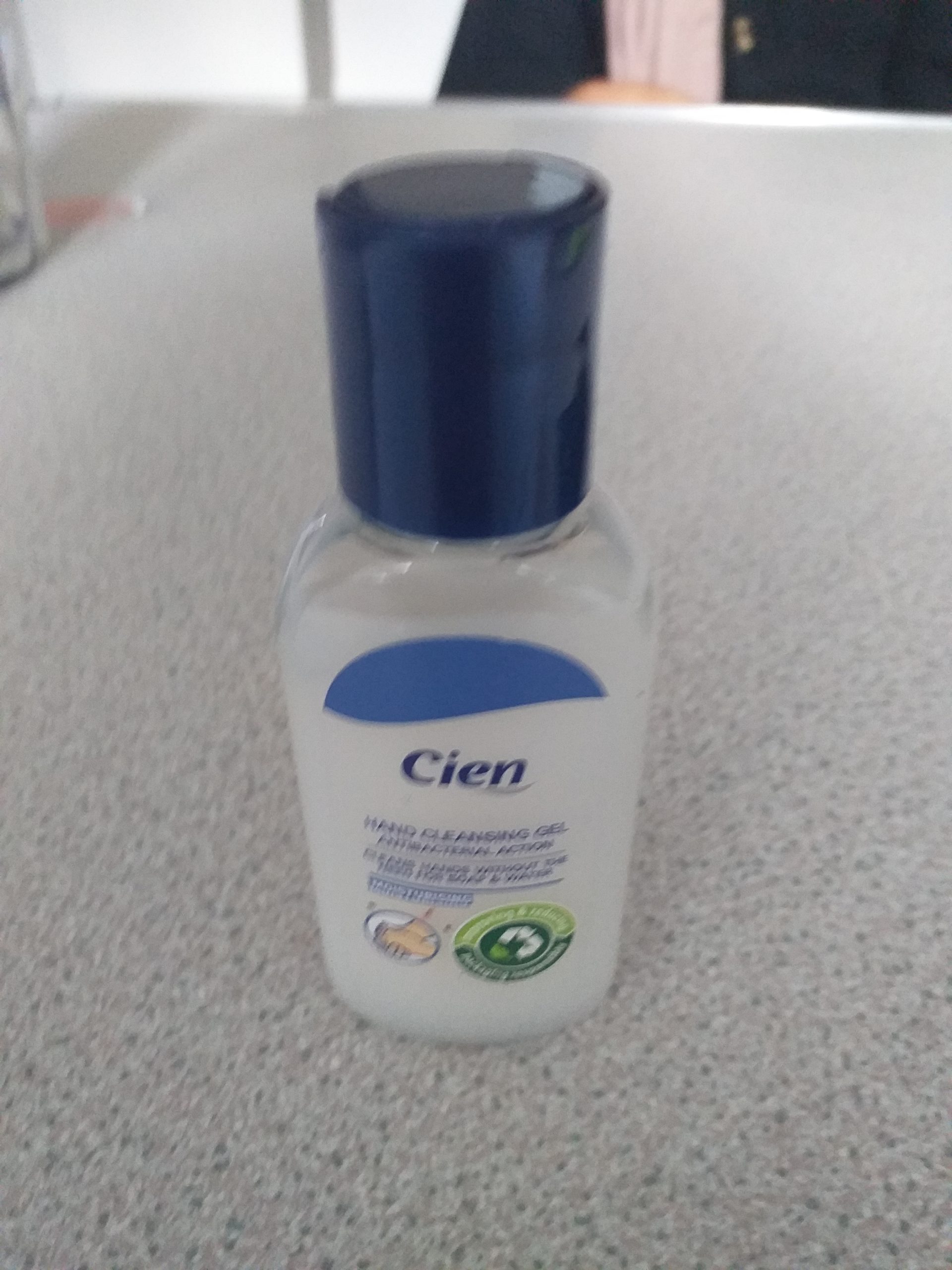

| Natulala upang maipasa ang Covid-19

Si Lindsey, na may edad na 15, ay "natakot" na ang kanyang lola, na tumira sa kanya, ay mahawaan ng Covid-19. Naranasan na niya ang pagkabalisa noon at naramdaman niyang naging malala ito sa panahon ng pandemya nang ang mga panganib ay lubhang nakakatakot para sa kanya. Ang takot na ito ay tumaas nang bumalik siya sa paaralan pagkatapos ng unang lockdown. “Doon kami nagkaroon ng napakaraming lockdown na pabalik-balik... 'pwede tayong bumalik, ngayon hindi na', parang, bakit tayo babalik-balik kung may mas malaking panganib pa doon?'... Palagi akong pumapasok [mula sa paaralan], gawin ang sinabi nila, maghugas ng kamay, magsanitize, minsan magpapalit ako ng damit para maisip kong mas malapitan ko ang isa o dalawa] [sa aking lola] malayo at palaging nagtatanong, 'para saan mo ginagawa 'yan?' 'Bakit mo ginagawa ito, hindi mo na kailangan', hindi nila kailangang mag-alala tungkol sa kung ano ang dapat kong alalahanin." Covid-19 sa malapitan Si Ali, may edad na 20, ay pansamantalang nakatira sa isang hotel sa panahon ng pandemya habang naghahanap ng asylum. Siya ay naatasan ng isang silid kasama ang tatlong iba pa, na hindi niya inaasahan. Ang pagbabahagi ng isang maliit na silid sa mga estranghero ay masikip sa pinakamahusay na mga oras - "hindi gaanong personal na espasyo" - ngunit ang takot na mahuli ang Covid-19 mula sa isa't isa, o mula sa pagiging nasa abalang mga communal space ng hotel, ay naging partikular na mahirap ang karanasan. "Hindi ko alam na magsasalo ako sa iisang kwarto... Lahat ng nahawakan mo kailangan nating pag-isipan... maiisip mo lahat... paulit-ulit lang na ginulo mo ang parehong bagay. Kailangan mong bumaba [sa cafeteria] at pagkatapos ay marami akong nakikitang tao, maghihintay ka sa pila... baka mahawa ka ng Covid, nagkaroon ako ng sakit sa ulo. Nakaramdam ako ng sakit sa ulo ng iba. parang wasak ang buong katawan ko... habang kasama ko ang tatlong tao sa isang kwarto, na hindi madali... Hindi ka nila inilagay sa ibang kwarto o anupaman.” |

Pinataas na mga paghihigpit: Sa ilang mga kaso, ang mga bata at kabataan ay naapektuhan ng nakakaranas ng mga paghihigpit na naiiba sa o mas matindi kaysa sa ibang mga tao dahil sa kanilang mga kalagayan. Para sa ilan, ito ay dahil sa pisikal na kapansanan o pagkakaroon ng kondisyong pangkalusugan, lalo na kapag ang pagsasara ng mga pampublikong palikuran ay naglimita sa kung gaano katagal sila makakalabas ng bahay o kung gaano kalayo ang kanilang mararating. Para sa ilan, ang pagiging klinikal na vulnerable sa kanilang sarili, o sa isang klinikal na vulnerable na pamilya, ay nangangahulugan ng pagharap sa mas mataas na mga paghihigpit. Para sa iba, ito ay dahil sa pagiging nasa isang secure na setting o setting ng pangangalaga at pakiramdam na kailangan nilang sundin ang mga panuntunan nang mas mahigpit kaysa sa iba. Ang pagiging apektado ng karagdagang mga paghihigpit ay partikular na emosyonal na hamon para sa ilang mga bata at kabataan kapag ang mga paghihigpit ay pinaluwag para sa iba at nadama nila na hindi kasama dito.

| Pinaghihigpitan ng pagsasara ng mga pampublikong espasyo

Inilarawan ni Mark, na may edad na 14, kung paano naging mas mahirap para sa kanya ang kanyang kondisyon sa kalusugan na lumabas ng bahay kapag sarado ang mga pampublikong lugar, kabilang ang mga palikuran, at kung paano siya at ang kanyang pamilya ay kailangang mag-adjust sa pagpaplano ng mga bagay nang mas maingat kung gusto nilang subukan at lumabas. “Malinaw na kaya naming mamuhay nang may [kalagayan ng aking kalusugan] ngunit pagkatapos, alam mo, ang mga bagong implikasyon tulad ng pagdistansya mula sa ibang tao, ang mga bagay ay nagsasara... ito ay gumawa ng isang malaking pagkakaiba at kailangan naming gumawa ng iba't ibang mga solusyon at ito ay malinaw naman na mas magtatagal upang makarating sa mga lugar, kung minsan ay dalawa, tatlong beses, ngunit kami pa rin, kahit papaano ay makakarating kami doon at tiyakin lamang na walang tunay na pagkakataon [malamang] pagkakataon na magkaroon ng aksidente o isang bagay na tulad niyan… napakahirap ng panahon, lalo na, alam mo, sa mga problema sa pisikal na kalusugan na mayroon ako, hindi ito nangangahulugan na maaari na lang akong pumasok sa isang tagong lugar o dumiretso sa banyo o kung ano pa man... hindi ito nangangahulugan na maaari akong pumunta sa mga saradong lugar... Kinailangan ko pa ring sundin ang mga patakaran, dahil lang sa medyo naiiba ako, hindi ito nangangahulugan na ang aking sarili ay maaari na.” Nakalimutan ng iba bilang isang batang tagapagtanggol Si Casey, may edad na 15, ay may kapatid na madaling kapitan ng sakit. Inilarawan ni Casey kung paano siya tumulong na protektahan ang kanyang kapatid sa panahon ng pandemya, kung gaano kahirap ang patuloy na protektahan nang magbukas ang lipunan pagkatapos ng unang lockdown at kung paano niya nadama na ang kanyang mga pangangailangan ay ganap na nakalimutan ng mga nakapaligid sa kanya. Pakiramdam niya ay tila hindi naiintindihan ng mga tao na ang mga kabataan ay nagsasanggalang din. “Noong lumabas kami sa [lockdown] ngunit pagkatapos ay inaasahan pa rin kaming magsasanggalang… habang ang iba ay nasa labas at gumagawa ng mga bagay-bagay, tila nakalimutan na nila ang tungkol sa mga taong nagsasanggalang, lalo na kung hindi sila tulad ng mga matatandang tao… parang ang mga ito ay kumilos na parang lahat ay bumalik sa normal… o [parang] ang tanging mga tao na nasa bahay lamang ay mga matatanda.” |

Pagkagambala sa suporta: Ang ilang mga bata at kabataan ay naapektuhan ng pagkagambala sa pormal na suporta at mga serbisyo sa pangangalagang pangkalusugan, partikular na ang mga serbisyo sa kalusugan ng isip, sa panahon ng pandemya, pati na rin ang pagkawala ng paaralan bilang pinagmumulan ng suporta o pagtakas mula sa anumang mga paghihirap sa tahanan. Bagama't ang ilan ay umangkop sa pagkawala ng personal na pakikipag-ugnayan, nakita ng iba na mahirap makipag-ugnayan sa telepono at online na contact at hindi gaanong suportado. Inilarawan din ng mga nakapanayam ang nakakaranas ng mga pagkaantala at hindi pagkakapare-pareho sa dalas at kalidad ng suporta at iniisip na ang mga serbisyong kanilang pinagkakatiwalaan ay nasa ilalim ng presyon. Ang pagkagambalang ito ay maaaring maging mas mahirap na makayanan ang pandemya para sa mga nasa mapanghamong sitwasyon na.

| Kawalan ng personal na suporta sa isang krisis sa pamilya

Inilarawan ni Charlie, na may edad na 20, kung gaano kahirap na hindi makita nang personal ang kanyang social worker sa panahon ng pandemya nang maramdaman niyang nasisira ang kanyang kinalalagyan ng foster care. Nahirapan siyang maging bukas tungkol sa sitwasyon sa mga tawag sa telepono at hindi nakuha ang emosyonal na suporta na natanggap niya dati. "Sa tingin ko, hindi si Covid ang dahilan kung bakit nasira ang placement ko pero talagang nag-ambag ito... Nasira ang placement at kumbinsido sila na malakas ang placement namin. Kaya gusto kong ipagpatuloy iyon at, parang, huwag magreklamo... [With my social worker] magkakaroon kami ng phone-calls but then it'd be like my foster mum would be there. Like to have any, how would be there. Like to have, how would be there. Feeling ko talaga… [Bago ang pandemic] isasama sana nila ako para maghapunan o kung ano ano pa… o uupo sila sa kwarto ko at tingnan lang kung okay na ang lahat o susunduin ako sa school at mga bagay-bagay na ganyan para lang magkaroon ka ng kaunting one-to-one time para makapag-usap... Kaya ang hindi magkaroon ng ganoon ay talagang mahirap... [Walang] access, tulad ng, naiwan akong mag-isa sa mga therapist at mga social worker noon. kaunti pa at talagang nalungkot." Nahihirapang makipag-ugnayan sa suporta sa kalusugan ng isip sa telepono Inilarawan ni George, na may edad na 20, ang pagkaranas ng depresyon sa panahon ng pandemya at pagkuha ng tulong ng kanyang ina upang makakuha ng referral para sa therapy sa pakikipag-usap. Nagkaroon na siya ng in-person therapy dati at talagang nahirapan siyang kumonekta sa isang bagong therapist sa telepono. Bagama't naging maayos ang pakikitungo niya sa kanyang pamilya, hindi siya kumportableng magsalita mula sa kanyang kwarto kung saan maririnig siya. Huminto siya sa therapy pagkatapos ng ilang session. "Wala akong pag-aalinlangan sa pagsasabi ng mga bagay-bagay sa aking pamilya. Pero parang, sabihin kung gusto kong mag-open up tungkol sa isang bagay na hindi ko naman talaga gustong madaanan ng aking mga magulang... at pagkatapos ay marinig ako ng isang bagay, mag-iwan ng isang bagay... Kailangan ko lang magkaroon ng pisikal na iyon, tulad ng, face-to-face na koneksyon para talagang maramdaman kong kaya kong mag-open up sa mga tao, ngunit sa pamamagitan ng telepono ay talagang walang koneksyon, tulad ng AI na iyon,' boses.” |

Nakakaranas ng pangungulila: Ang mga naulila sa panahon ng pandemya ay nakaranas ng mga partikular na paghihirap kung saan ang mga paghihigpit sa pandemya ay humadlang sa kanila na makita ang mga mahal sa buhay bago sila mamatay, pinigilan sila sa pagluluksa tulad ng gagawin nila sa mga normal na panahon, o ginawang mas mahirap na makita ang pamilya at mga kaibigan at madama ang suporta sa kanilang kalungkutan. Inilarawan ng ilan na tinitimbang ang pagkakasala at takot na lumabag sa mga patakaran upang makita ang isang mahal sa buhay bago sila namatay, kumpara sa pagkakasala sa hindi pagkikita sa kanila at takot na baka mamatay silang mag-isa. Ang ilan sa mga may mahal sa buhay na namatay dahil sa Covid-19 ay inilarawan ang karagdagang pagkabigla ng kamatayan na nangyayari nang napakabilis, na ginagawang natatakot sila para sa kanilang sarili at sa iba.

| Nagulat sa biglaang pangungulila

Naranasan ni Amy, na may edad na 12, ang pagkamatay ng isang mahal na kaibigan ng pamilya sa Covid-19 sa unang lockdown. Inilarawan niya ang kanyang pagkagulat sa nangyari at kung gaano ito kahirap iproseso. “Madalas siyang pumupunta tulad ng weekend at pumupunta siya para sa isang inihaw na hapunan, at lagi niya akong dinadalhan ng mga regalo at tulad ng mga sweets at iba pa, at parang close lang talaga kami, parang literal na parang isa siyang lolo at lola sa akin... At pagkatapos noong Covid, noong lockdown, nagkasakit siya ng Covid-19, at parang hindi siya magaling sa teknolohiya, kahit na hindi kami makatawag ng mabuti sa kanya. out she'd died it was really upsetting, like that threw me off a lot... Bata pa ako, at sinubukan kong alalahanin ang lahat ng magagandang alaala ngunit ang naalala ko lang ay namatay siya, at hindi ko na siya makikitang muli, at hindi na kami nakapunta sa kanyang libing dahil may mga paghihigpit... ang huling beses na nakita ko siya ay wala na iyon sa susunod na linggo, at pagkatapos ay nakita mo iyon sa susunod na linggo. |

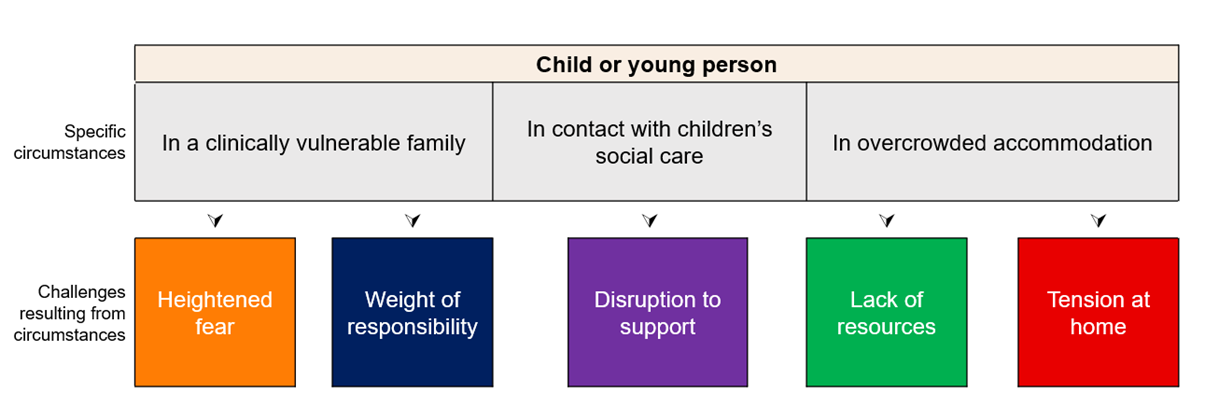

Ang epekto ng maraming mga kadahilanan

Ang pananaliksik na ito ay nakakuha rin ng mga karanasan sa pagiging apektado ng maraming hamon sa panahon ng pandemya kaugnay ng mga salik na tinalakay sa itaas. Ang Figure 3 sa ibaba ay naglalarawan kung paano ang kumbinasyon ng mga pangyayari sa panahon ng pandemya ay maaaring makaapekto sa isang indibidwal – sa kasong ito ay naninirahan sa masikip na tirahan, nagsasanggalang upang maprotektahan ang isang miyembro ng pamilya na may klinikal na bulnerable at nakakaranas ng pagkagambala sa suporta mula sa panlipunang pangangalaga ng mga bata. Ito ay maaaring magresulta sa mga bata at kabataan na nahaharap sa isang hanay ng mga hamon na nagpahirap sa buhay sa panahon ng pandemya.

Figure 3: Ang potensyal na epekto ng maraming salik sa isang indibidwal

Ang mga pag-aaral ng kaso sa ibaba ay nagbibigay ng ilang halimbawa kung saan ang mga nakapanayam ay naapektuhan ng kumbinasyon ng mga salik at ang mga hamon na kanilang kinaharap bilang resulta.

Sinasalamin ng case study na ito kung paano naapektuhan ng bigat ng responsibilidad at pagtaas ng takot ang isang kabataang may mga responsibilidad sa pangangalaga para sa kanyang magulang na may sakit sa klinika sa panahon ng pandemya.

| Responsibilidad at takot sa pag-aalaga sa isang taong may klinikal na kahinaan

Nicky, sa edad na 21, inilarawan ang pressure na naramdaman niya noong pandemya noong inaalagaan niya ang kanyang ina, na madaling masugatan pagkatapos ng transplant, at ang "nakalumpong takot" na magkasakit siya ng Covid-19. Sa kanyang nakatatandang kapatid na naninirahan malayo sa bahay at hindi nakadalaw, ang responsibilidad ay nasa kanya lamang. Inilarawan niya ang lahat ng pamimili, hindi makakuha ng delivery slot at kaya sumakay ng taxi papunta sa supermarket at maingat na dini-disinfect ang lahat bago ito dalhin sa loob. Samantala ang kanyang ina ay nahihirapan sa pagkawala ng pakikipag-ugnayan sa labas. Nakita ni Nicky ang kanyang sarili bilang isang matibay na tao sa normal na panahon ngunit sinabi na ito ay nasubok ng pandemya, hanggang sa punto na humingi siya sa kanyang GP ng suporta sa kalusugan ng isip. "Malinaw na kapag ang iyong ina at ang isang taong mahal mo higit sa anumang bagay ay gagawin mo lamang ito. Hindi ito isang tanong, oh, hindi ko ito kakayanin; Kailangan kong harapin ito dahil kailangan niya akong gawin ito ... ito ay ... napakasalungat dahil gusto kong alagaan siya ngunit, sa parehong oras, nais kong maging, tulad ng, iba pang mga tao at nanonood lamang ng maraming mga libro at nag-e-enjoy sa TV at nagbabasa ng maraming libro pagiging makakalimutin.” |

Ang sumusunod na halimbawa ay nagpapakita kung paano ang isang kabataang may mga responsibilidad sa pangangalaga na nakipag-ugnayan sa mga serbisyong panlipunan sa panahon ng pandemya ay naapektuhan ng tensyon sa tahanan at pagkagambala sa suporta.

| Pag-aalaga sa pamilya sa gitna ng pagkasira ng pamilya at pag-aalangan ng suporta

Si Mo, na may edad na 18, ay may mga responsibilidad sa pangangalaga bago ang pandemya, tumulong sa pag-aalaga sa kanyang dalawang kapatid na may espesyal na pangangailangan sa edukasyon at pagsuporta sa kanyang mga magulang sa pamamahala ng sambahayan dahil sa kanilang mga kahirapan sa kalusugan at limitadong Ingles. Ang relasyon ng kanyang mga magulang ay lumala at ang kanyang ama ay naging abusado hanggang sa punto na kailangan na siya ng pamilya na umalis, ngunit nang tumama ang pandemya ay wala na siyang ibang mapupuntahan. Inilarawan niya ang bigat ng sitwasyong ito. "Noon [mga serbisyong panlipunan] ay hindi talaga alam kung paano haharapin ito dahil parang hindi nila siya mapaghiwalay sa bahay dahil wala nang ibang madadala sa kanya. Hindi siya maaaring tumira sa iba at siya mismo ay masusugatan ... maraming mga argumento ... Sana maunawaan ng paaralan kung gaano kahirap ang mga bagay sa bahay at, alam mo, ang pagkakaroon ng isang bata na autistic sa bahay at palaging may mga problema sa pag-uugali sa bahay at magkasama marami sa akin... Sana ay nauunawaan ng pangangalaga ng lipunan ang mga pinsalang dulot nito sa pananatili ng aking ama sa tahanan.” |

Ang case study sa ibaba ay nagpapakita kung paano ang isang bata na nakipag-ugnayan sa parehong pangangalagang panlipunan ng mga bata at mga serbisyo sa kalusugan ng isip sa panahon ng pandemya ay naapektuhan ng pagkagambala sa suporta kasabay ng pagharap sa tensyon sa bahay.

| Pakiramdam ang pinagsama-samang pagkawala ng mga network ng suporta at serbisyo

Si Jules, na may edad na 20, ay umalis sa pangangalaga at bumalik sa kanyang magulang bago ang pandemya at nahihirapan, sa kalaunan ay muling lumipat. Nang tumama ang pandemya, napagtanto niya na ang hindi makatagpo sa mga kaibigan o makapunta sa kanyang part-time na trabaho ay makakasakit sa kanya, lalo na dahil nahihirapan na siya sa kanyang kalusugan sa isip. Natagpuan niya ang pakikipag-ugnayan sa pangangalaga sa lipunan ng mga bata na hindi pare-pareho sa panahon ng pandemya, palaging nakikita ng iba't ibang tao, at nadama niya na dapat ay nagkaroon siya ng access sa mas mahusay na suporta para sa kanyang kalusugan sa isip. “Iniisip ko lang na hindi ko makikita ang mga kaibigan ko, iyon ang pinakamalaking network ng suporta ko, noon pa man at kapag hindi maganda ang mga bagay sa bahay, ang pinakamagandang gawin ay lumabas na lang at makita ang mga kaibigan mo, nakaka-angat lang talaga ng mood mo… [Bago ang pandemic] Magiging maganda ang araw ko, lalabas ako at makikita ko ang mga kaibigan ko, gagawa ng magagandang bagay, pero pakiramdam ko, lahat ng klase ng pandemya ay natigil lang... bagay, tulad ng mga social worker o PAs³ o anumang bagay na tulad niyan, hindi nila gustong lumapit sa akin at parang 'Sa tingin ko ay makikinabang ka rito' o anumang bagay na katulad niyan... ang mga tao sa loob at labas ng pangangalaga tulad ng mga umalis sa pangangalaga o mga taong nasa pangangalaga, ay ilan sa mga pinaka-mahina na bata, mga tao. Pakiramdam ko dapat ay mayroon tayong hiwalay na pag-access sa mga serbisyo sa kalusugan ng isip o, alam mo, nagkaroon ng mas maraming pagkakataon na ma-access ang suporta dahil sa tingin ko maraming tao ang makikinabang mula doon." |

- ³ Sinusuportahan ng mga personal assistant (PA) ang mga indibidwal na mamuhay nang higit na nakapag-iisa, kadalasan sa kanilang sariling tahanan.

Mga salik na naging dahilan upang mas madaling makayanan ang pandemya

Sa ibaba ay binabalangkas namin ang mga salik na nagpadali para sa ilang mga bata at kabataan na makayanan ang pandemya, harapin ang mga hamon, at kahit na umunlad sa panahong ito.

Mga sumusuportang relasyon: Inilarawan ng mga bata at kabataan sa lahat ng edad kung paano sila tinulungan ng mga kaibigan, pamilya at mas malawak na komunidad na malampasan ang pandemya. Para sa ilan, ang pagiging nasa isang ligtas at matulungin na kapaligiran ng pamilya ay isang mahalagang kadahilanan sa paglikha ng mga positibong karanasan sa panahon ng pandemya. Ang pagkakaroon ng online na pakikipag-ugnayan sa mga kaibigan ay isa ring napakahalagang paraan upang labanan ang pagkabagot at paghihiwalay ng lockdown at para sa mga bata at kabataan na humingi ng suporta kung sila ay nahihirapan. Ang ilan ay naging bahagi ng mga bagong komunidad online sa panahon ng pandemya, mula sa pagkilala sa iba pang mga manlalaro hanggang sa pagsali sa isang bagong komunidad ng pananampalataya, at natagpuan ang mga ito na pinagmumulan ng suporta.

| Ang koneksyon ng pamilya ay nagdudulot ng kaginhawahan at pakikisama

Si Jamie, may edad na 9, ay nakatira kasama ang kanyang nanay, tiyahin at lolo't lola noong panahon ng pandemya. Nang walang mga kaibigang mapaglalaruan, nagpapasalamat siya na kasama niya ang kanyang tiyahin. "Sa simula [ng lockdown] mas nabigla ako, nalilito at nagulat. At habang tumatagal, mas naiinip ako at nakaramdam ako ng ligtas, kalmado at masaya... Tita ko iyon, parang pinasaya niya ako at hindi talaga siya nagkukwento tungkol sa nangyari... kung makakauwi ka sa pag-aaral, mas malulungkot ka dahil wala ka talagang kaibigan sa paaralan... pero wala akong kapatid sa school, pero wala akong kapatid sa trabaho. hindi naman ganoon ka-busy, so she used to entertain me and play with me... Arts and crafts, doing some role play, making, nakalimutan ko kung ano ang tawag dun, yung mga maliliit na tent thingies na yun, parang sa loob ng bahay mo ginagamit mo yung mga upuan at nilalagay mo na parang tela, yung den? Mga malalapit na kaibigan na nagbibigay ng suporta sa mahihirap na panahon Inilarawan ni Chris, na may edad na 16, kung paano naapektuhan ang kanyang relasyon sa kanyang ina sa panahon ng lockdown at kalaunan ay nasira. Bagama't masaya siyang nakatira kasama ang kanyang ama, ang "pagsabog" na ito ay hindi inaasahan at mahirap na makayanan at ginawa siyang mas mulat sa pangangalaga sa kanyang kalusugan sa isip. Inilarawan niya kung paano nakatulong sa kanya ang paglalaro at pakikipag-usap sa kanyang mga kaibigan araw-araw sa panahon ng lockdown na malampasan ang mga bagay-bagay at kung paano siya naging komportable sa paglipas ng panahon na pag-usapan ang kanyang nararamdaman sa kanyang grupo ng pagkakaibigan. “We'd literally talk every single day... as long as I can remember like five people who are all really really close, and you know, like then you have like mutual friends around that, but like lima kaming [naging] palagi lang lahat sa [aming] PC... so wala talagang nagbago sa amin, we were still talking the same way we would in person. Just because we were all kind of Covid, it was never been that kind of friendship. na nagkaroon kami... Talagang nagbago [ang pandemya] tulad ng kung gaano ako kaingat sa pakikipag-usap sa mga tao tungkol sa kalusugan ng isip... binago ang paraan ng pakikipag-usap ko tungkol sa sarili kong damdamin, at pagkatapos ay pakikipag-usap sa aking mga kaibigan at tungkol sa kanilang mga damdamin." |

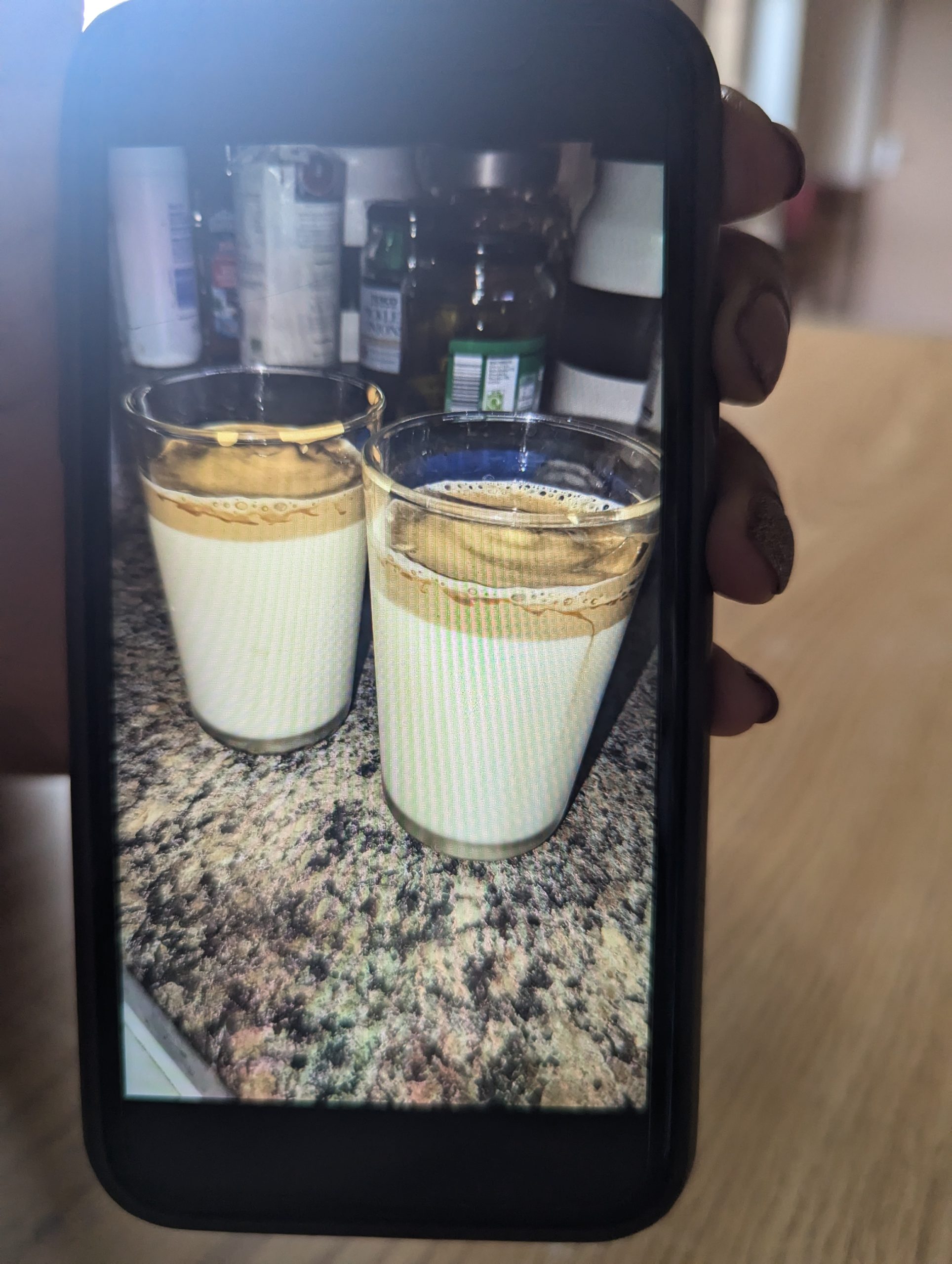

Paghahanap ng mga paraan upang suportahan ang kagalingan: Inilarawan ng mga bata at kabataan sa lahat ng edad ang mga bagay na ginawa nila sa bahay noong panahon ng pandemya upang sadyang protektahan ang kanilang kapakanan at bumuti ang pakiramdam kapag sila ay nahihirapan. Mula sa pagkuha ng sariwang hangin at pag-eehersisyo, sa paggugol ng oras sa mga alagang hayop, sa panonood o pagbabasa ng isang bagay na escapist, ang pagkakaroon ng kakayahang gumawa ng isang bagay na positibo o nakakaaliw para sa kanilang sarili ay napakahalaga para sa mga bata at kabataan sa panahon ng pandemya. Natuklasan din ng ilan na ang paglalagay ng isang gawain ay makatutulong sa kanila upang maiwasan ang pagkabagot at pagkahilo.

| Maghanap ng mga paraan upang makaramdam ng kasiyahan

Lou, sa edad na 10, ay nakatira kasama ang kanyang mga magulang at nakababatang kapatid na babae sa panahon ng pandemya. Kapag gusto niyang gumawa ng isang bagay para gumaan ang pakiramdam niya sa panahon ng lockdown, gusto niyang manood ng TV, makinig ng musika at kumanta. Higit sa lahat, gustung-gusto niyang gumawa ng mga palabas kasama ang kanyang kapatid na babae, na hinimok ng kanyang ina na nagmungkahi na patuloy silang mag-drama sa bahay bilang bahagi ng muling paggawa ng kanilang nakagawiang gawain sa paaralan at pagkatapos ng paaralan. Ito ang naging paborito niyang aktibidad noong lockdown. "Ako at ang aking kapatid na babae ay madalas na gumawa ng mga maliliit na palabas para kay mommy... mahilig kami sa mga sayaw at dati ay gusto naming gumawa ng isang routine... At gusto ng nanay ko na i-rate ito at sasabihin niya na ito ay talagang maganda. At talagang nagustuhan ko iyon... Nakaramdam ako ng kalmado at... talagang masaya at nasasabik tungkol dito. Dahil talagang kailangan kong gawin kung ano ang talagang nagpapasaya sa akin... [namin] naaaliw ang isa't isa at tinulungan ang isa't isa na manatiling positibo at hindi gusto ang isa't isa na manatiling positibo at hindi gusto ang isa't isa na manatiling positibo at hindi gusto ang isa't isa. Paghahanap ng aliw sa isang treasured libro Si Ari, na may edad na 18, ay nagkaroon ng mahirap na buhay sa tahanan sa panahon ng pandemya at nasa listahan ng naghihintay para sa suporta sa kalusugan ng isip. Inilarawan nila kung paanong ang pagbabasa ng paboritong libro ay isang mapagkukunan ng kaginhawahan at pagtakas para sa kanila at nagdala ng larawan nito kasama nila sa kanilang panayam. “Ito ay tulad ng pagbabasa ko noong panahon ng pandemya, gusto kong basahin ito ng marami at pakinggan ko rin ito ng marami, tulad ng isang audio book, dahil talagang nagpapaliwanag ito sa akin, at nagbigay ito sa akin ng isang bagay na gusto kong ma-distract ang aking isipan mula sa lahat ng nangyayari... ang istilo ng pagsulat ay parang talagang... liriko at patula... ito ay isang bagay na gusto kong panatilihing kalmado ako at gusto ko ang mga bagay na iyon. |

Gumagawa ng isang bagay na kapakipakinabang: Ang kakayahang gumawa ng isang bagay na kapaki-pakinabang sa panahon ng pandemya – kung minsan ay hindi inaasahan – ay nakatulong sa mga bata at kabataan na makayanan ang pagkabagot, alisin sa kanilang isipan ang mga alalahanin, at maging mas motibasyon sa panahon ng tinatawag na “empty time” ng lockdown. Kabilang dito ang pagbuo ng mga umiiral na kasanayan at interes at pagtuklas ng mga bagong hilig at talento. Maaari rin itong magkaroon ng kapana-panabik na mga kahihinatnan kung saan ang paghahanap ng isang bagay na gagawin ay nagbibigay ng inspirasyon sa mga bagong libangan o nagbubukas ng mga direksyon sa akademiko o karera sa hinaharap.

| Pagtuklas ng isang hindi inaasahang libangan na nagpasimula ng isang karera

Natagpuan ni Max, na may edad na 18, ang pandemya na isang nakaka-stress na panahon, lalo na dahil ang kanyang ama ay clinically vulnerable at gumugol ng ilang oras sa ospital. Kinailangan niyang huminto sa paglalaro ng team sport sa panahon ng lockdown at wala na siyang ibang libangan. Ngunit sa pagsasara ng mga barbero, na-inspire siyang magpagupit ng kanyang sariling buhok, pagkatapos ay nalaman niyang talagang nasiyahan siya sa paggupit ng buhok ng ibang tao at kaya nagbukas ng bagong direksyon para sa kanyang kinabukasan. “Ganyan ako nakapasok sa barbering... Natuto lang akong magpagupit ng buhok ko sa lockdown... Nagpagupit ako ng buhok ng tatay ko pero gusto lang niyang kalbo lahat [kaya] ginagawa ko lahat ng design sa ulo niya tapos pinunit ko after... Kailangan ko talagang magpagupit sa lockdown at halatang walang bukas na barbero kaya nag-order na lang ako ng isang pares ng clippers at na-enjoy ko na ang sarili ko... Nag-enjoy ako sa sarili ko… hobby… [mula noon] Nagawa ko na ang level 2 ko sa barbering college at naipasa ko na ang aking mga pagsusulit... [Kung wala ang Covid] Wala akong ganoong qualification ngayon at talagang nag-e-enjoy ako sa barbering, naghahanap lang ako ng apprenticeship sa isang shop ngayon.” Pakiramdam ng pagmamataas at kasiyahan mula sa pagkamit ng isang layunin Si Elliott, may edad na 12, ay binigyang inspirasyon ni Captain Tom na itakda ang kanyang sarili sa isang hamon at makalikom ng pera para sa kawanggawa. Sinuportahan ng kanyang ina, nagpasya siyang kumpletuhin ang 100 lap ng paglalakad sa paligid ng bloke, na pagkatapos ay naging 200. Ang mga kapitbahay ay lalabas ang kanilang mga ulo upang makita siya at ito ay naging isang tunay na pagsisikap sa pangangalap ng pondo sa komunidad: "Sa oras na mayroon kaming isang oras sa isang araw ay ginugugol ko iyon sa paggawa ng ilang laps sa aking bloke hanggang sa ako ay umabot sa isang daang, at pagkatapos ay nagkaroon kami ng malaking kasiyahan, at kami ay talagang natapos na ang dalawang libong libra. Isa lang talagang magandang alaala para sa akin at tinutulungan ako nitong isipin ang mga magagandang bahagi sa Covid at mas kaunti ang tungkol sa mga masasamang bahagi… [Nakalikom kami ng pera] para sa NHS, sa palagay ko, magsaliksik patungo sa... tulad ng mga pag-iniksyon, hindi ko alam kung ano ang tawag dito... ang mga pagbabakuna kaya napunta ito sa NHS, ang pananaliksik sa Covid... oo [I did feel proud], it was a really fun thing to keep me occupied.” |

Kakayahang magpatuloy sa pag-aaral: Inilarawan ng mga bata at kabataan kung paano kung nakapagpatuloy sila sa pag-aaral sa panahon ng pandemya, sa kabila ng malawakang pagkagambala sa edukasyon at mga hamon ng malayong pag-aaral, ito ay nagbigay-daan sa kanila na maging positibo at makakamit nila ang gusto nila sa paaralan, trabaho at buhay. Ito ay maaaring dahil sa pagtanggap ng tulong na kailangan nila mula sa mga magulang o kawani ng pagtuturo, sa pagpasok sa paaralan habang ang iba ay nasa bahay (para sa mga anak ng pangunahing manggagawa), o pagtamasa ng mas nababaluktot at malayang diskarte sa pag-aaral. Ang matagumpay na malayuang pag-aaral ay sinusuportahan din sa pamamagitan ng pagkakaroon ng access sa mga naaangkop na device para sa pag-aaral at sa ilang mga kaso sa pamamagitan ng pagsunod sa isang gawain sa bahay.

| Umunlad sa pamamagitan ng isang malayang diskarte sa pag-aaral

Si Jordan, na may edad na 13, ay nasiyahan sa pag-aaral sa tahanan at pagtuturo sa kanyang sarili nang higit pa kaysa sa pag-aaral, na nagpatibay sa kanyang tiwala sa kanyang kakayahan at nagtulak sa kanya na maging isang guro. Pakiramdam niya ay nakahingi siya ng tulong mula sa pamilya (ang isang magulang ay nagtatrabaho sa bahay at ang isa ay inalis sa trabaho), nadama na ligtas siya, at may mga opsyon na makipag-ugnayan sa mga guro sa pamamagitan ng email o telepono kung kailangan niya. Sinunod niya ang parehong gawain tulad ng ginagawa niya sa paaralan ngunit nag-click sa mga link upang tapusin ang mga gawain nang mag-isa. "Maaari mong pindutin ang Maths link o ang English link o ang science link o, tulad ng, iba pa. At maaari mo, at pagkatapos ay pindutin mo lang ang lesson na iyon at gawin ang gawain na itinakda para sa lesson na iyon... Sa isang punto ay papapasukin ako ng nanay ko pero parang ayaw ko talagang pumasok dahil parang magaling ako sa pag-aaral sa bahay at nag-e-enjoy ako... Gusto ko, gusto ko, gusto ko. parang gusto kong maging guro kapag mas matanda na ako... Kaya gusto ko, gusto ko lang, parang, iiskedyul ito, at kung minsan ay nagpapanggap akong guro at, parang, nagtuturo, parang, ang mga teddy ko... maaari mong palaging, mag-like, mag-email sa [mga guro] o tumawag sa kanila at, parang, kapag ginawa ko ang aking trabaho, kung minsan gusto ko, gusto ko, magpadala ng mga larawan at talagang 'yun,' oh, maganda 'yan sa kanila. |

Mahalagang tandaan na ang lahat ng mga salik na ito ay pinagtibay ng paggugol ng oras online – mula sa pakikipag-ugnayan sa mga kaibigan hanggang sa paglalaro hanggang sa pag-aaral ng mga bagong bagay mula sa mga online na tutorial. Sa kabila ng mga paghihirap na naranasan ng ilan sa pamamahala sa dami ng oras na ginugol nila online, at ang panganib ng pagkakalantad sa online na pinsala, ang pagiging online ay maaaring maging mahalagang mapagkukunan ng pakikipag-ugnayan sa lipunan, kaginhawahan, pagtakas at inspirasyon para sa mga bata at kabataan sa panahon ng pandemya.

3. Paano naapektuhan ang buhay sa panahon ng pandemya

3.1 Tahanan at pamilya

Pangkalahatang-ideya

Ang seksyong ito ay nagsasaliksik ng mga karanasan sa tahanan at buhay pampamilya sa panahon ng pandemya, na binibigyang-diin ang hanay ng mga hamon at responsibilidad sa tahanan na nagpahirap sa pandemya lalo na para sa ilang mga bata at kabataan at ang kontribusyon ng mga sumusuportang relasyon at mga gawain ng pamilya sa pagtulong sa mga bata at kabataan na makayanan. Sinusuri din namin kung paano naramdaman ng mga bata at kabataan na naapektuhan sila ng pagkagambala sa pakikipag-ugnayan sa mga miyembro ng pamilya na hindi nakatira sa kanila noong panahon ng pandemya.

Buod ng Kabanata |

|

| Mga sumusuportang aspeto ng buhay pamilya

Mga hamon sa tahanan Pagkagambala sa pakikipag-ugnayan ng pamilya Pangwakas na pananalita |

|

Mga sumusuportang aspeto ng buhay pamilya

Sa napakaraming oras na ginugol sa bahay sa panahon ng lockdown, ang pagiging nasa isang ligtas at matulungin na kapaligiran sa tahanan ay mahalaga. Inilarawan ng mga bata at kabataan kung paano naging mas kasiya-siya o mas madaling makayanan ang kanilang karanasan sa pandemya dahil sa pakikipag-ugnayan sa pamilya at pagkakaroon ng mga aktibidad, gawain, at pagdiriwang. Kagiliw-giliw na tandaan na ang mga bata at kabataan ay hindi palaging pinasasalamatan ang kanilang mga magulang para sa paglalagay ng mga aktibidad na ito sa lugar at paggawa ng ilang mga sandali na hindi malilimutan, ngunit malinaw na ang ilan ay nakinabang mula sa mga pagsisikap ng mga nasa hustong gulang na gawing mas positibo ang buhay sa tahanan.

Mga relasyon sa pamilya

Ang paggugol ng mas maraming oras na magkasama bilang isang pamilya ay isang mahalagang aspeto ng karanasan sa pandemya para sa mga bata at kabataan sa iba't ibang edad. Gaya ng na-explore sa itaas, dahil ang ilan ay nakakulong sa bahay nang magkasama ay humantong sa mga tensyon, o nagpalala ng mga tensyon kung saan sila umiiral na. Gayunpaman, ang mga salaysay ng buhay ng pamilya ay nagsasama rin ng mga positibong karanasan, kung minsan ay kabilang sa mga hamon. Sa ilang mga kaso, sinasabing ang pandemya ay naglalapit sa mga miyembro ng pamilya at nagpapatibay ng mga relasyon. Mahalaga ito dahil sa papel na ginampanan ng mga suportang relasyon sa pagtulong sa mga bata at kabataan na makayanan ang panahon ng pandemya.

| “Ngayon alam ko na na mahalaga na makipag-bonding sa iyong pamilya... [sa panahon ng lockdown] marahil ay mas mabilis kaming nag-bonding, higit pa at dahil mas marami kaming ginagawang aktibidad at bagay na magkasama." (Edad 9)

"Gustung-gusto kong nasa bahay lang at makasama ang aking ina at ama at mga kapatid. Akala ko ito ay maganda." (Edad 16) "Sa palagay ko bilang isang pamilya, lahat kami ay malapit [bago ang pandemya], ngunit mas malapit kami ngayon; Sa palagay ko mayroon kaming lockdown upang pasalamatan iyon." (Edad 16) |

Ang ilan sa mga nakapanayam sa kanilang mga late teenager o twenties ngayon ay sumasalamin na sila ay nagpapasalamat para sa kumpanya ng kanilang pamilya at na ito ay isang espesyal na oras na magkasama.

| "I think it definitely made me appreciate just being at home more and enjoying time at home with my parents. Just doing simple things. Not always being busy." (Edad 16)

“Siguro dumaan ako sa stage na iyon tulad noong S24 kung saan ayoko makisama sa pamilya ko. Pero dahil wala ka talagang choice, mamasyal ako kasama sila at iba pa. Sa palagay ko oo, naging mas malapit kami bilang isang pamilya." (Edad 17) "Talagang nakipag-bonding ako sa aking ina nang higit kaysa karaniwan kong ginagawa, dahil napilitan ako, kaya ito ay isang magandang bagay." (Edad 18) “Sa aking kapatid na babae at nanay, ito ay higit na dahilan upang gumawa ng higit pang mga bagay na magkasama at oo umupo sa hardin at mag-usap nang maraming oras dahil iyon lang ang magagawa namin… tiyak na pinatibay nito ang aming mga relasyon dahil pakiramdam ko ay muli naming [normal] na tinatanggap namin na nakikita namin sila araw-araw ngunit wala ka talagang oras na magkasama." (Edad 21) "I think, like, we definitely would, like, have dinner together more. Kasi hindi naman talaga namin yun ginawa bukod noong bata pa kami ng kapatid ko... So that was quite nice in that regard to, like, spend time all together as a four of us dahil hindi naman ganoon katagal dahil nasa uni ako sa puntong iyon at bago pa ako pumasok sa uni, matagal na kaming magkasama ng kapatid ko." (Edad 22) |

- 4 Ang S2 ay ang ikalawang taon ng sekondaryang edukasyon sa Scotland.

Kahit na may alitan sa pagitan ng magkapatid, naalala ng ilang mga bata at kabataan na masaya pa rin silang gumugol ng mas maraming oras sa isa't isa at maghanap ng mga paraan upang labanan ang pagkabagot nang magkasama.

| “Sa tingin ko ito ay talagang mabuti para sa amin dahil tulad ng kahit na nagsimula kami ng mga argumento; parang nag-bonding kami dahil may ginagawa kami.” (Edad 12)

"Ako at ang aking kapatid na babae - talagang napunta kami sa chess. Ganito kami nainip. Nagkaroon kami ng chess board at nagsimula kaming maglaro ng laro pagkatapos ng laro." (Edad 15) "We started bingeing stuff, completing games. And it was just really like, again, I felt like [my brother] was my friend now." (Edad 18) "Ako at ang aking nakatatandang kapatid na babae, nagsimula kaming maging mas malapit at... pagiging mabait sa isa't isa. Dahil palagi kaming nag-aaway ngunit kapag nasa bahay kami napagtanto namin ... kailangan naming makipag-usap sa isa't isa at maglaro." (Edad 18) “Masarap magkaroon ng mga kapatid at hindi ko gugustuhing maranasan iyon kung wala sila… may tao sa bahay na makakasama mo at makakasama mo ang kasiyahan.” (Edad 16) |

Ang pagkakita ng higit pang mga magulang na nagtatrabaho mula sa bahay o furlough ay binanggit ng ilan bilang isang positibong aspeto ng lockdown (na hindi naranasan ng mga anak ng pangunahing manggagawa).

| “Pakiramdam ko, noong lockdown [ang tatay ko na nag-trabaho nang malayo at ako] ay gumugol ng mas maraming oras na magkasama kaya iyon, parang, parang, medyo mas malapit sa oras na iyon dahil, parang, halatang gumugol kami, parang, buong araw na kasama ang isa't isa. (Edad 14)

“[Ang aking ama na nasa bahay] ay medyo nagbigay sa akin ng pagkakataong maugnay o gumawa ng isang bono - isang mas malaking bono sa aking ama." (Edad 18) "Sa pangkalahatan kami ay gumugol ng mas maraming oras na magkasama dahil sila nanay at tatay ay nasa trabaho nang marami, kaya medyo maganda na ang lahat ay nandiyan sa lahat ng oras... Dati kaming naglalakad tulad ng araw-araw at tulad ng paglalaro ng mga board game at iba pa. At pagkatapos ay palagi kaming tulad ng isang programa sa TV na pinapanood." (Edad 16) "Ang iyong mga magulang, kung sila ay mga mahahalagang manggagawa tulad ng sa akin, sila ay palaging gumagawa ng kanilang mga trabaho. Wala talagang maraming oras na ginugugol namin na magkasama. Kami ay gumugol ng hapunan at almusal at tanghalian ngunit iyon lang. Naaalala ko na nakaupo ako doon isang araw ... Natapos ko ang lahat ng aking trabaho para sa paaralan at nakaupo lang ako doon habang hinahagis ito ng bola at sinasalo ito nang paulit-ulit hanggang sa makauwi ang aking ina." (Edad 12) |

Mga aktibidad at gawain ng pamilya

Ang mga bata at kabataan, ngunit lalo na ang mga nasa elementarya sa panahon ng pandemya, ay inalala ang mga aktibidad ng pamilya bilang isang mahalagang alaala ng pandemya. Naranasan ang mga ito sa mga bracket ng kita at kasama ang paglalaro ng mga board game, pagkakaroon ng movie night, paggawa ng mga sining at sining, pagluluto, pagluluto, at pag-eehersisyo sa Joe Wicks pati na rin ang pagkain nang magkasama. Isang malakas na alaala din para sa ilan ang paglalakad bilang isang pamilya. Kasama dito ang paglalakad sa paligid upang tingnan ang mga larawan ng mga bahaghari na idinikit ng mga tao sa kanilang mga bintana sa panahon ng pandemya bilang simbolo ng pag-asa at suporta para sa National Health Service (NHS).

| “Gumawa kami ng ilang iba't ibang mga bagay at ginamit namin, tulad ng, Foam Clay upang, tulad ng, ilagay ito sa mga ito, tulad ng, clay, tulad ng, mga kaldero at mga bagay at gumawa ng aming sarili, tulad ng, mga hugis at bagay at pagkatapos ay kung minsan ay gusto namin, maghurno o magluto o kung ano sa hapon at mayroong, tulad ng, maraming mga sining at sining at mga bagay-bagay. (Edad 14)

“Iniisip ko ang tungkol sa 'oh, mayroon akong napakagandang alaala'... ang isang naisip ko tungkol sa magandang paghihikayat mula sa aking ina ay tulad ng ginawa namin sa online na PE... Joe Wicks... Naaalala ko sa decking ang aking ina ay parang 'halika, kaya mo ito, halika'." (Edad 11) "Minsan sa Covid ginagawa namin ang bagay na ito kung saan tulad ng bawat linggo na gagawin namin, ang taong ito ay pipili kung anong disenyo ng pagkain ang gusto nila at pagkatapos ay gagawin nila kasama ang aking nanay o tatay... at pagkatapos ay gusto naming pumili ng isang bansa, alam mo, tulad ng ginawa ng aking kapatid na babae sa Italya ... [Sa ilang gabi] lahat ay pumili ng isang pelikula. Ilalagay namin ito sa isang sumbrero at pagkatapos ay pipili kami ng isa." (Edad 11) "Ilang beses na gusto namin, inilipat ang sofa sa aking katulad na hardin at gusto naming dalhin ang TV at ilagay ito upang magustuhan ang bangkong ito at pagkatapos ay gusto naming magkaroon ng isang panlabas na gabi ng pelikula." (Edad 12) "Lahat kami ay namamasyal, iyon ang ginawa namin bilang isang pamilya. Literal kaming naglalakad na parang tatlong oras na paglalakad, iyon marahil ang pinaka ginagawa namin... nanood kami ng maraming pelikula, si Joe Wicks... Gusto naming kumain nang magkasama at karaniwan ay hindi kami... Mas marami kaming nakikita sa isa't isa at talagang mas matagal kaming magkasama." (Edad 14) "Palagi kaming naglalakad sa bahaghari at nakikita ang lahat ng bahaghari at gusto naming gumawa ng mga bagong bahaghari araw-araw at gusto naming punan ang aming buong bintana. Dahil sa aming lumang bahay ay mayroon kaming napakalaking bintana sa harap at pupunuin lang namin ito ng lahat ng iba't ibang bahaghari at pagkatapos ay panoorin ang mga tao na dumaan at makita sila." (Edad 11) |

Naalala rin ng matatandang bata at kabataan ang mga aktibidad ng pamilya tulad ng paglalakad, panonood ng pelikula, at pagkain bilang isang pamilya. Gayunpaman, magkakahiwalay din sila, lalo na kung mayroon silang sariling mga screen. Nadama ng ilan na ang kanilang pakikipag-ugnayan sa mga miyembro ng pamilya ay talagang limitado dahil lahat sila ay magkasama sa bahay.

| “Pakiramdam ko ay lahat kami ay gumagawa lamang ng aming sariling bagay, kahit na ako, ang aking kapatid, at ang aking ama sa ilalim ng isang bubong. Lahat kami ay nasa iba't ibang iskedyul. Nagkita lang talaga kami for dinner.” (Edad 20)

"Sa panahon ng pandemya, maliban sa makatotohanang, naglalakad sa ibaba para sa mga bagay-bagay, hindi kami masyadong nakikipag-ugnayan." (Edad 13) |

Para sa mga pamilyang may hardin, minsan ito ay nagiging focus para sa mga aktibidad ng pamilya sa unang lockdown. Kasama sa mga aktibidad sa labas na inilarawan ng mga bata at kabataan ang paglalaro at pag-eehersisyo, pagtatanim ng sarili nilang prutas at gulay, paglubog sa araw, at pagkain sa labas kasama ang kanilang mga pamilya. Na-appreciate ng ilan na masuwerte silang magkaroon ng ganitong espasyo sa labas.

| “Ang aking ina ay binigyan kami ng isang post sa netball... dahil lamang ito ay isang bagay na maaari naming makuha sa hardin. Ito ay isang bagay upang mailabas [kami ng aking kapatid na babae]. And I think it was, like, medyo nag-enjoy ako. And I was like, this is really fun... I was really lucky to have the garden.” (Edad 13)

“Kapag wala kaming Covid, magkakaroon kami ng mga barbecue sa aming hardin at maglalaro din kami ng kuliglig at football at basketball sa aming hardin." (Edad 10) "Maswerte ako, nagkaroon ako ng magandang bahay na may hardin, napapaligiran ng mga bukid, na may access ako." (Edad 18) |

Dapat tandaan na ang mga nakapanayam ay kasama rin ang mga bata at kabataan na walang access sa isang hardin, na malamang na nasa isang urban o suburban setting at sa isang mas mababang kita na sambahayan. Sa ilang pagkakataon, ang kakulangan ng hardin ay inilarawan bilang nagpapahirap sa pandemya. Halimbawa, inilarawan ng isang bata ang paglipat sa kanyang lolo't lola upang magkaroon ng access sa isang hardin, nang nadama ng kanyang ina na nagkasala na sila ay "na-stuck sa isang flat". Gayunpaman, ito ay higit na hindi binanggit ng mga walang hardin at hindi nila pinag-uusapan ang tungkol sa pagkawala - kahit na hindi nila naranasan ang mga positibong aspeto na inilarawan ng mga may hardin.

| “Nakatira kami sa isang napakataas na flat... medyo mahirap dahil wala kaming sariwang hangin. Kung gusto namin ng sariwang hangin, ilalabas namin ang aming ulo sa bintana at huminga lang… hindi maganda... walang hardin.” (Edad 13)

"Siguro gusto kong magkaroon ako ng hardin ngunit hindi talaga - sa tingin ko ay hindi talaga kami masyadong naapektuhan." (Edad 21) |

Sa wakas, binigyang-diin ng mga account kung paano nakinabang ang ilang bata mula sa mga pagsisikap na ginawa upang markahan ang mga espesyal na okasyon sa bahay nang pinigilan sila ng mga paghihigpit sa pandemya sa paglabas. Naalala ng ilang mga bata at kabataan ang mga alternatibong paraan ng pagdiriwang bilang isang pamilya at pagpapahalaga sa mga ito.

| “Dahil hindi kami makakalabas tulad ng para sa kaarawan ng aking ama ginawa namin siya tulad ng araw na ito ng Mexico kung saan nakuha namin siya tulad ng isang poncho at isang sumbrero at ginawa siyang Mexican na pagkain para sa kanyang kaarawan. (Edad 12)

“[Noong kaarawan ko ang tatay ko] ay nag-disco sa aming decking at ito ay, parang, napakaingay kaya lahat ng kalye ay, parang, sumasayaw sa kanilang mga tahanan at kung ano-ano... Talagang masaya, pero, kasi, parang, nakita ko pa rin ang mga kaibigan ko [na pumunta sa ilalim ng hardin] ngunit ang layo lang nila." (Edad 12) "Karaniwan akong may party [para sa aking kaarawan] ngunit sa taong iyon tulad ng aking nanay na gusto niya, naglalakad kami at maraming sasakyan ang nasa dulo ng kalsada at parang lahat ng aking mga kaibigan at pamilya at lahat sila ay nagsasabi ng maligayang kaarawan... Napakasaya. Tulad ng dahil wala akong nakitang sinuman sa isang buwan at ako ay talagang masaya na makita ang lahat." (Edad 14) "Ang mas malawak na pamilya na hindi namin madalas makita... At may mga selebrasyon tulad ng Eid na hindi talaga namin maipagdiwang nang husto at maayos dahil sa mga pag-iingat sa kaligtasan. Kaya nagpadala kami ng pagkain sa mga bahay ng isa't isa." (Edad 15) |

Mga hamon sa tahanan

Sa ibaba ay detalyado namin ang hanay ng mga hamon sa tahanan na nakaapekto sa ilang mga bata at kabataan sa panahon ng pandemya. Sinisiyasat namin ang mga tensyon sa pamilya, at kung paano ito mapapalala ng karagdagang hamon ng pamumuhay sa masikip na tirahan.5 Sinusuri din namin kung ano ang naramdaman ng mga bata at kabataan na naapektuhan sila nang may nahawahan ng Covid-19 sa sambahayan at ang mga karagdagang hamon sa tahanan para sa mga may responsibilidad sa pangangalaga.

- 5 Ang kahulugan ng masikip na tirahan ay: "isang sambahayan na may mas kaunting mga silid kaysa sa kailangan nito upang maiwasan ang pagbabahagi, batay sa edad, kasarian at relasyon ng mga miyembro ng sambahayan. Halimbawa, isang hiwalay na silid-tulugan ay kakailanganin ng: isang mag-asawa o nagsasama-sama; isang taong may edad na 21 o higit pa; 2 anak ng parehong kasarian na may edad na 10 hanggang 20 taong gulang; 2 anak ng anumang kasarian na wala pang 10 taong gulang." Mangyaring tingnan: Mga masikip na kabahayan – GOV.UK Ethnicity facts and figures

Mga tensyon sa pamilya

Kahit na para sa mga pamilyang naging maayos, ang pagiging stuck sa loob nang magkasama sa panahon ng lockdown ay naalala bilang isang mapagkukunan ng tensyon. Inilarawan ng mga bata at kabataan ang pakiramdam na "nakakulong", "claustrophobic", at "nasa ibabaw ng isa't isa". Ito ay totoo lalo na para sa mga may kapatid, at kahit na kung saan sila ay nasisiyahan sa pagsasama ng isa't isa ang pare-parehong pisikal na kalapitan ay maaaring humantong sa mga pagtatalo.

| "Well, I appreciated the time I got to spend with them. Pero sobrang nakaka-stress." (Edad 17)

"Ang pamumuhay kasama ang iyong kapatid sa lahat ng oras, tulad ng, na-stuck sa isang lugar, tulad ng, tiyak na humantong ito sa maraming, tulad ng, mas maraming away kaysa dati." (Edad 17) "Sobrang nagka-butted heads lang [kami ng kapatid ko. Kumbaga, hindi kami magkasundo. Medyo maayos na ngayon pero buong buhay namin hindi kami nagkakasundo. So kapag magkasama kami palagi, parang sa bahay, medyo sobra." (Edad 19) "Maaari kang maging literal na pinakamahusay na mga buds sa kanila, nagkakaroon ng mga tensyon, at ilang araw ay nawawala ito at ang buong bahay ay napopoot sa isa't isa." (Edad 16) "Medyo naging stressful [sa bahay] kasi yung nakababatang kapatid ko nung time na yun, parang makulit siya na parang masungit sa school at mga ganyan. Tapos dinala niya pauwi, parang noong naka-lockdown na bawal siya magustuhan kahit pumasok sa school o lumabas at kung ano-ano pa. So, naglalabas siya ng mga bagay-bagay sa bahay na lang. at tulad ng pagwawalang-bahala tulad ng kung ano ang sinabi sa kanya at iba pa… na-stress ang aking ina, at na-stress siya dahil wala rin siyang magagawa, at pagkatapos ay ang aking isa pang kapatid na babae... na masasabi mo na ito ay iniistorbo sa kanya, ngunit hindi rin siya umimik kaya, sa tingin ko ito ay parang nalulumbay talaga ang bahay, ngunit ang lahat ay parang sinusubukan na lumayo sa isa't isa pagkatapos. (Edad 22) "Ang mga tao ay masyadong marami sa espasyo ng mga tao, sa palagay ko, masyadong mahaba." (Edad 21) |

Nadama ng ilan sa mga nakapanayam na ang kakulangan ng espasyo sa bahay ay maaaring nagpahirap sa kanila, lalo na kung saan ang magkapatid ay nakikibahagi sa mga silid-tulugan o may kakulangan ng espasyo para maglaro, tapusin ang mga gawain sa paaralan, o magkaroon ng oras na mag-isa. Ang mga kabataan sa panahon ng pandemya ay lubos na nadama ang tungkol sa kawalan ng sariling espasyo.

| “Matagal kaming magkasama, nababahala sa isa't isa.” (Edad 12)

"Lahat kami ay nasa ilalim ng iisang bahay, wala kaming isang napakalaking, malaking bahay, kaya't ang alam mo lang ay sinusubukan mong magtrabaho, gumawa ng unibersidad, mahusay na gawain sa paaralan mula sa bahay, at malinaw naman pareho sa Zoom, at pareho ng, 'shut up!'" (Aged 21) "Sa tingin ko mas marami kaming nag-away at gusto lang naming magtalo dahil lang sa pagiging malapit sa quarters na parang lahat ng tao, oh, kailangan mo ng space mo minsan." (Edad 19) “Walang mauupuan, tulad ng, kung may nang-aagaw sa iyo, maririnig mo pa rin silang huminga mula sa kabilang silid.” (Edad 21) "Maraming tao ang nagsabi na mayroon silang masyadong maraming oras para mag-isip [sa panahon ng lockdown]. Ngunit dahil may mga batang bata sa aking bahay, mas kaunting oras ako dahil ako ay palaging, hindi ako kailanman nagkaroon ng katahimikan upang mag-isip sa aking isip dahil palaging may nagsasalita." (Edad 18) |

Sa mga sitwasyong ito, ang paghahanap ng mga paraan upang mag-ukit ng ilang espasyo ay mahalaga. Inilarawan ng ilang mga bata at kabataan na nasa espasyo ng isa't isa sa pisikal, ngunit lumilikha ng ilang paghihiwalay sa pamamagitan ng pagiging online, o sa pamamagitan ng paggamit ng mga headphone na nakakakansela ng ingay upang ipahiwatig na gusto nilang mapag-isa at hindi makausap.

| “Sa palagay ko ay hindi ko gaanong nakausap ang aking mga magulang dahil lahat kami ay nasa iisang bahay, isang maliit na bahay, ngunit ang lahat ay nasa kakila-kilabot na mood... [kami ng aking ina] ay halos hindi nag-uusap sa isa't isa, para lamang dalhan ako ng parang pagkain at kung ano-ano, para pag-usapan ang tungkol sa paaralan, ngunit dahil madalas akong nasa online na mga tawag at parang naka-attach sa aking iPad, hindi ko siya kinakausap." (Edad 18)

“Matagal kami sa iisang kwarto kasama ang isa't isa ngunit hindi kami masyadong nakikipag-usap sa isa't isa dahil pareho din kaming online, tulad ng sa sarili naming maliit na bula." (Edad 20) |

Ang ilang mga bata at kabataan, lalo na ang mga nasa sekondaryang edad sa panahon ng pandemya, ay nadama na mas nakipagtalo sila sa mga magulang sa panahon ng lockdown. Minsan ito ay sanhi ng paglalagay ng mga magulang ng mga panuntunan at paghihigpit sa kanila, halimbawa ng pagpapakilala ng mga rota para sa paggamit ng mga console ng laro ng mga kapatid o paglilimita sa dami ng oras na ginugol sa mga screen. Nakasentro rin ang mga argumento sa mga gawain at kung gaano karaming gawain sa paaralan ang ginagawa. Naalala rin ng mga bata at kabataan ang mga argumento kung saan ang mga magulang ay naglagay ng mga paghihigpit sa kung sino ang maaari nilang makita sa labas ng bahay o kung maaari silang lumabas, kahit na pinahintulutan sila ng mga pambansang paghihigpit na gawin ito.

| “Marahil ay mas nagalit ako sa [aking mga magulang] dahil hindi ako pinayagang gawin ang ilang bagay... Nainis ako... hindi nila ako pinapayagang gawin ang ilan sa mga bagay na gusto kong gawin... tulad ng pagkuha ng Xbox, na mayroon ako ngayon ngunit hindi ko magawa noon dahil hindi nila ako pinapayagan." (Edad 13)

"Medyo maraming argumento ang natanggap namin, partikular na ako lang at ang nanay ko tungkol sa pag-alis namin sa paaralan." (Edad 19) "Nagdulot ito ng maraming, tulad ng, ng mas maraming away sa aking ina, dahil mas matagal kaming magkasama. Tulad ng, hindi bababa sa bago siya makakuha, tulad ng, pahinga at ako ay nakakuha ng pahinga kapag ako ay nasa paaralan o sa labas o kung ano ang ginagawa. Ngunit, tulad ng, kami ay medyo magkadikit lang ng higit sa isa't isa... Ako ay, parang, napakagulo, napakagulo, wala akong ayos, kung saan-saan. skin... Palagi lang akong nag-aaway ng nanay ko, parang mga kalokohang bagay.” (Edad 18) "Ngayon [ako at ang aking ina] ay maayos ngunit tulad ng, bago at sa panahon ng pandemya ay palaging tulad ng, alitan, alitan, alitan, alitan, alitan." (Edad 21) "Naaalala ko na ang aking ina ay talagang inis dahil sa unang bahagi siya ay talagang paranoid tungkol sa pandemya sa palagay ko at ako at ang aking ama ay lumabas kami para sa paglalakad ... at siya ay tulad ng, 'Oh aking Diyos paano mo magagawa iyon'?" (Edad 21) |

Alam ng ilang bata at kabataan ang mga tensyon sa pagitan ng mga matatanda sa kanilang sambahayan. Mas malamang na mapansin ng mga kabataan sa kanilang mga kabataan noong panahong iyon kung ang pandemya ay nagdulot ng pagkasira sa relasyon ng kanilang mga magulang. Ito ay nauugnay sa pagkawala ng trabaho, mga pinansiyal na alalahanin, at umiiral na mga hamon sa relasyon, pati na rin ang pagtatrabaho mula sa bahay at pagkakaroon ng pagbabahagi ng espasyo sa pamilya. Ito ay maaaring magdulot ng pag-aalala, stress, at kawalan ng katiyakan para sa mga bata at kabataang kasangkot.

| "Napaka-tense [ng atmosphere sa bahay. Very, very tense... kasi walang gustong makipag-usap sa isa't isa... because [my mom and her partner] had a really shattered relationship, stressed with everything and we never talked to each other." (Edad 14) |

Ang pananaliksik na ito ay nakakuha rin ng mga karanasan ng pag-igting sa tahanan mula sa mga nasa partikular na kalagayan. Ang ilang mga kabataan ay nagbahagi ng mga paghihirap na kanilang naranasan sa panahon ng pandemya kung saan ang kanilang mga pamilya ay hindi sumusuporta sa kanila LGBTQ+ (tomboy, bakla, bisexual, transgender, queer at iba pa). Ito ay mula sa mga karanasan ng hindi maipahayag ang kanilang sarili o makipag-usap nang hayagan sa kanilang mga pamilya, hanggang sa pagiging masungit ng kanilang pamilya sa kanila. Ang mga kabataang ito ay partikular na naapektuhan ng lockdown dahil hindi sila nakatakas sa kanilang kapaligiran sa tahanan at hindi nila ganap na maipahayag ang kanilang sarili o ipahayag ang kanilang sarili sa paraang gusto nila.

| “Nang lumabas ako sa [aking ina] ay talagang isang pagalit na kapaligiran ang maupo." (Edad 20)