Crynodeb gweithredol

Nid yw'r adroddiad hwn yn cynrychioli barn yr Ymchwiliad. Mae'r wybodaeth yn adlewyrchu crynodeb o'r profiadau a rannwyd gyda ni gan y rhai a fynychodd ein Byrddau Crwn yn 2025. Mae'r amrywiaeth o brofiadau a rannwyd gyda ni wedi ein helpu i ddatblygu themâu yr ydym yn eu harchwilio isod. Gallwch ddod o hyd i restr o'r sefydliadau a fynychodd y bwrdd crwn yn atodiad yr adroddiad hwn.

Mae'r adroddiad hwn yn cynnwys disgrifiadau o effeithiau iechyd meddwl, hunan-niweidio a marwolaeth. Gall y rhain fod yn ofidus i rai. Anogir darllenwyr i geisio cymorth os oes angen. Darperir rhestr o wasanaethau cefnogol ar wefan Ymchwiliad Covid-19 y DU.

Ym mis Mai 2025, cynhaliodd Ymchwiliad Covid-19 y DU drafodaeth ford gron a oedd yn canolbwyntio ar effaith y pandemig ar y system gyfiawnder a'r system garchardai, a'r system fewnfudo a lloches a'u defnyddwyr. Cynhaliwyd y drafodaeth ford gron ar draws tair trafodaeth grŵp.

Effaith ar y system gyfiawnder a'r system garchardai

Disgrifiodd cynrychiolwyr sut yr effeithiodd y pandemig ar wahanol agweddau ar y system gyfiawnder ar draws plismona, achosion llys, gwasanaethau cymorth i ddioddefwyr a rheoli carchardai.

Bu’n rhaid i’r heddlu addasu i newidiadau mewn ymddygiad troseddol yn ystod y cyfnod clo. Fe wnaethon nhw hefyd gymryd cyfrifoldebau ychwanegol wrth orfodi rheoliadau Covid-19 a chamu i mewn i helpu pobl oedd angen gwasanaethau cyhoeddus, fel gwasanaethau cymdeithasol, a gaeodd yn ystod y pandemig. Arafodd cynnydd ymchwiliadau’r heddlu o ganlyniad i gyfyngiadau ar gyswllt personol gan ei gwneud hi’n anoddach casglu tystiolaeth a datganiadau tystion.

Achosodd y pandemig oedi mewn gwrandawiadau llys o ganlyniad i'r angen i weithredu mesurau cadw pellter cymdeithasol, y terfyn ar nifer y bobl a ganiateir i gael mynediad i lysoedd, gan gynnwys tystion a dioddefwyr a'r newid i ddefnyddio technoleg. Yn ogystal, arafwyd cynnydd gan unigolion a brofodd yn bositif am Covid-19 ac a orfododd ynysu.

Bu symudiad tuag at wrandawiadau llys o bell. Roedd gan hyn rai pethau cadarnhaol, gan wella effeithlonrwydd a galluogi'r llysoedd i gynnal prosesau cyfreithiol mewn amgylchiadau eithriadol. Fodd bynnag, roedd rhai ymarferwyr cyfreithiol yn ei chael hi'n anodd addasu i ddarparu cyngor ac eiriolaeth effeithiol gan ddefnyddio technoleg.

Gwnaeth y pandemig hi'n anoddach i lawer o ddioddefwyr gael mynediad at gyfiawnder, gan gynnwys riportio troseddau i'r heddlu neu fynychu gwrandawiadau llys. Roedd pobl o grwpiau agored i niwed yn ofnus ac yn amharod i ymgysylltu â'r system gyfiawnder oherwydd y risgiau iechyd. Gwnaeth y newid i wrandawiadau o bell hi'n anoddach i'r rhai nad oedd ganddynt y dechnoleg gywir na'r sgiliau digidol gael mynediad at lysoedd o bell. Gwaethygwyd rhwystrau iaith ac ni allai rhai gyfathrebu â'r heddlu a chynrychiolwyr cyfreithiol yn effeithiol oherwydd nad oedd aelodau'r teulu yn gallu darparu cymorth cyfieithu o ganlyniad i bellhau cymdeithasol. Teimlwyd hefyd fod defnyddio gwrandawiadau o bell ac oedi yn y llys wedi digalonni pobl rhag riportio troseddau ac ymgysylltu ag achosion. Ychwanegodd ansicrwydd ynghylch amseroedd prosesu at yr amharodrwydd hwn. Gostyngodd adroddiadau troseddau yn ystod y cyfnod clo ac arhosasant yn is ar ôl y pandemig. Priodolwyd hyn yn rhannol i lai o ymddiriedaeth yn y system gyfiawnder oherwydd oedi yn y llys yn gysylltiedig â'r pandemig.

Yn ôl cynrychiolwyr, arweiniodd y penderfyniad i oedi rhyddhau carcharorion yn gynnar o dan y Cynllun Rhyddhau Dros Dro Diwedd y Ddalfa, a oedd yn caniatáu i garcharorion risg isel o fewn y ddau fis olaf o'u dedfryd gael eu rhyddhau'n gynnar, at amodau gwaeth mewn carchardai. Roedd hyn yn cynnwys gorlenwi a chyfundrefn garchardai fwy cyfyngol i leihau lledaeniad Covid-19. Yn ogystal, roedd peidio â chael mynediad at weithgareddau arferol a rhaglenni ymddygiad yn ei gwneud hi'n anoddach i garcharorion ddangos risg is mewn gwrandawiadau parôl, gan ychwanegu at broblemau capasiti carchardai.

Roedd carcharorion yn cael eu hynysu yn eu celloedd am gyfnodau hir o hyd at 23 awr y dydd dros fisoedd lawer, gan effeithio ar eu hiechyd meddwl. Ychwanegodd hawliau ymweld llai yn ystod y pandemig at eu hynysu ac roedd yn golygu bod ganddynt gysylltiad cyfyngedig â ffrindiau a theulu a chefnogaeth ganddynt.

Trafodwyd hefyd effaith mynediad llai at ofal iechyd mewn carchardai yn ystod y pandemig. Rhoddodd cynrychiolwyr enghreifftiau o broblemau wrth geisio cael mynediad at wasanaethau iechyd corfforol a meddyliol, yn ogystal ag oedi wrth roi triniaeth feddygol i garcharorion oedd yn sâl. Dywedwyd bod hyn wedi arwain at ganlyniadau iechyd difrifol fel gwaethygu cyflyrau hirdymor neu fethu diagnosis. Er bod y symudiad tuag at ofal iechyd o bell wedi caniatáu i rai ymgynghoriadau iechyd barhau, roedd carcharorion a oedd yn wynebu rhwystrau iaith yn cael anhawster i lywio'r system heb gael dehonglwyr yn bresennol bob amser.

Dywedwyd bod data cyfyngedig yn mesur effaith rhai o fesurau’r pandemig ar y system gyfiawnder. Credwyd bod hyn wedi’i waethygu gan ddiffyg rhannu gwybodaeth ar draws adrannau’r llywodraeth. Roedd hyn yn golygu nad oedd yn bosibl olrhain holl effeithiau’r newidiadau.

Roedd cynrychiolwyr yn credu bod gwersi allweddol y gellid eu dysgu i leihau'r effaith ar y system gyfiawnder mewn pandemig yn y dyfodol. Dywedasant fod angen gwelliannau strategol wrth gynllunio a rheoli'r system o dan amodau pandemig, gan gynnwys gwella achosion llys o bell a darparu mwy o gyfleoedd i garcharorion ymarfer corff a chael cysylltiad â ffrindiau a theulu. Roeddent hefyd yn teimlo bod angen dysgu o arfer gorau ar gyfer cefnogi carcharorion, gan gynnwys defnyddio technoleg i gynnal cysylltiadau cymdeithasol. Disgrifiasant gasglu data cyson fel rhywbeth hanfodol i ddeall cyfraddau trosglwyddo o fewn carchardai ac effeithiau eraill y pandemig ar y system gyfiawnder.

Effaith ar y system fewnfudo a lloches

Arweiniodd cyfyngiadau teithio a roddwyd ar waith yn ystod y pandemig at ostyngiad mewn mudo i'r DU i ddechrau. Fodd bynnag, cynyddodd mudo wrth i gyfyngiadau'r pandemig lacio, gyda chyfranogwyr yn tynnu sylw at y ffaith bod y pandemig yn cyd-daro â diwedd ymadawiad y DU o'r Undeb Ewropeaidd. Dywedodd yr Arsyllfa Ymfudo, yn ystod y pandemig, fod ceisiadau am loches wedi gostwng tua 20% i ddechrau, ond cynyddodd croesfannau afreolaidd, yn enwedig ar gychod bach, yn sylweddol erbyn 2021-2022. Awgrymasant, yn hytrach na bod y pandemig yn atal y croesfannau hyn, fod y galw am y gweithgareddau hyn, ac amlder y gweithgareddau hynny, wedi cynyddu.

Roedd heriau gyda chael data mudo oherwydd bod y ffynonellau arferol o niferoedd mudo fel yr Arolwg Teithwyr Rhyngwladol wedi'u hoedi. Roedd hyn yn golygu nad oedd yn glir pwy oedd yn dod i mewn ac allan o'r DU yn ystod y pandemig, gan ei gwneud hi'n anodd i lunwyr polisi ddeall a datblygu ymatebion i batrymau mudo.

Arweiniodd y pandemig at oedi sylweddol wrth brosesu achosion mewnfudo, gan arwain at ôl-groniad. Cyfyngodd cyfyngiadau cadw pellter cymdeithasol yn sylweddol ar y gallu i gynnal cyfweliadau mewnfudo a chael mynediad at ddogfennau yn bersonol. Cafodd rhai cyfreithwyr mewnfudo eu rhoi ar ffyrlo, gan adael pobl heb arweiniad.

Roedd rhai manteision i fewnfudwyr o gynlluniau a gyflwynwyd gan y Swyddfa Gartref yn ystod y pandemig. Roedd y rhain yn cynnwys cynllun consesiwn Covid-19, Consesiwn Estyniad y Coronafeirws a'r Consesiwn Yswiriant Eithriadol. Roedd y cynlluniau hyn yn caniatáu i'r rhai y byddai eu caniatâd i aros wedi dod i ben yn ystod y pandemig aros yn y DU tra bod cyfyngiadau pandemig ar deithio ar waith. Fodd bynnag, eglurodd cynrychiolwyr fod diffyg canllawiau clir ar y cynlluniau hyn a'r cyfyngiadau arnynt, yn enwedig mewn perthynas â chymhwysedd a therfynau amser, yn ei gwneud hi'n anodd i ymarferwyr cyfraith mewnfudo gynghori mewnfudwyr. Mewn llawer o achosion, collodd mewnfudwyr eu statws mewnfudo rheolaidd ac o ganlyniad eu gallu i weithio a chael mynediad at wasanaethau hanfodol.

Cynyddodd y pandemig ynysu cymdeithasol i fewnfudwyr oherwydd eu bod wedi'u torri i ffwrdd o'u rhwydweithiau arferol a'u gwasanaethau cymorth hanfodol. Trafododd cynrychiolwyr sut y gadawodd cynnydd mewn ffioedd fisa a chyfreithiol ynghyd â llai o gyfleoedd i weithio (gyda llawer o fewnfudwyr yn gweithio yn yr economi anffurfiol neu mewn sectorau yr effeithiwyd arnynt yn wael gan y pandemig) lawer o fewnfudwyr yn dlawd ac achosodd ddibyniaeth eang ar fanciau bwyd.

Trafodasant hefyd sut y gwaethygodd y pandemig amodau tai mudwyr yn y DU. Dywedasant fod y dibyniaeth fwy ar westai a barics i gartrefu mudwyr yn arwain at orlenwi ac yn aml yn eu rhoi mewn mwy o berygl o ddal Covid-19.

Defnyddiwyd caethiwed unigol i atal lledaeniad Covid-19 mewn canolfannau cadw mewnfudwyr. Roedd y cyfranogwyr o'r farn bod hyn yn gwneud carcharorion yn ynysig ac yn ofnus ac, ynghyd â mynediad cyfyngedig at gymorth iechyd meddwl, arweiniodd at waethygu iechyd meddwl ymhlith mudwyr a oedd yn cael eu cadw.

Gwelwyd mynediad at ofal iechyd i fewnfudwyr hefyd yn broblem yn ystod y pandemig, er gwaethaf y ffaith nad oedd y GIG yn codi tâl ar fewnfudwyr am ofal iechyd yn gysylltiedig â Covid-19. Esboniodd cynrychiolwyr sut roedd gan fewnfudwyr ofnau hirdymor ynghylch gwasanaethau gofal iechyd yn eu hadrodd i'r Swyddfa Gartref, a allai effeithio ar eu statws mewnfudo neu olygu y byddai'n rhaid iddynt dalu. Tynnodd y pandemig sylw hefyd at rwystrau presennol i fewnfudwyr gael mynediad at ofal iechyd, megis peidio â chael rhifau GIG neu wybodaeth yn eu hiaith. Roedd y problemau hyn yn golygu bod mynediad mewnfudwyr at ofal iechyd a brechlynnau sy'n gysylltiedig â Covid-19 yn gyfyngedig yn ystod y pandemig.

Darparodd cynrychiolwyr wersi allweddol i'w dysgu ar gyfer y system fewnfudo a lloches. Roeddent eisiau systemau mwy dibynadwy ar gyfer casglu data mudo, er mwyn galluogi gwell dealltwriaeth o'r gymuned fudol a'r ffordd orau o'u cefnogi. Tynasant sylw at yr angen i sefydlu fframweithiau i gynnal cefnogaeth achosion mewnfudo yn ystod pandemig, gan gynnwys darparu statws gweithiwr allweddol i gynrychiolwyr cyfreithiol yn fwy cyson. Pwysleisiasant y gwendidau unigryw y mae mudwyr yn eu hwynebu, yn enwedig o ran cadw mewnfudwyr a mynediad at ofal iechyd a thai, ac roeddent am i'r rhain gael eu cydnabod wrth lunio polisïau ar gyfer pandemigau yn y dyfodol.

Rhan A: yr effaith ar y system gyfiawnder

Themâu allweddol

Effaith ar weithrediad sefydliadau cyfiawnder troseddol

Rôl yr heddlu

Newidiodd rôl yr heddlu yn ystod y pandemig gan fod ganddynt gyfrifoldebau ychwanegol, gan gynnwys cynnal trefn gyhoeddus a sicrhau bod pobl yn cadw at ganllawiau'r pandemig. Disgrifiodd Cyngor Cenedlaethol Prif Swyddogion yr Heddlu sut y gostyngodd y galwadau arferol i'r heddlu drwy 999 ac 101 (y rhif cyswllt di-argyfwng ar gyfer heddluoedd yng Nghymru a Lloegr) yn gynnar yn y pandemig a daeth yr heddlu'n bennaf yn bryderus am Covid-19 a thorri rheolau Covid-19.

| “ | Newidiodd rhywfaint o rôl yr heddlu [oherwydd] rheoliadau Covid-19. Yn wir, roedd llawer o'n galwadau yn ymwneud â Covid-19 a thorri cyfyngiadau.”

– Cyngor Cenedlaethol Prif Swyddogion yr Heddlu |

Dywedwyd hefyd fod y math a nifer y troseddau a gyflawnwyd wedi newid. Er enghraifft, nododd yr Inquest fod llai o droseddau economi nos oherwydd bod lleoliadau ar gau. Esboniodd Cyngor Cenedlaethol Prif Swyddogion yr Heddlu hefyd fod cau siopau nad ydynt yn hanfodol wedi lleihau troseddau manwerthu a bod cyfraddau byrgleriaethau domestig wedi gostwng yn gyflym oherwydd bod pawb gartref. Ychwanegon nhw fod canlyniad y gostyngiad yn y math hwn o drosedd yn golygu bod yr heddlu wedi gallu dargyfeirio adnoddau tuag at ymchwiliadau eraill a bod hyn wedi arwain at gynnydd mewn arestiadau yn ymwneud â'r ymchwiliadau hynny yn gynnar yn y pandemig.

Fodd bynnag, cynyddodd lefelau ymddygiad gwrthgymdeithasol, gan gynnwys torri rheolau Covid-19, mwy o anghydfodau rhwng cymdogion a chynnydd mewn troseddau cyffuriau. Dywedwyd hefyd fod cynnydd mewn troseddau a thwyll ar-lein.

Roedd y pandemig yn golygu bod llawer o wasanaethau cyhoeddus fel gwasanaethau cymdeithasol a sefydliadau cymorth ar gau neu'n llai hygyrch oherwydd na allent weithredu'n bersonol. Dywedodd cynrychiolwyr fod yn rhaid i'r gwasanaethau a arhosodd ar agor weithredu fel rhwyd ddiogelwch o ganlyniad, gan ddarparu cymorth y tu allan i'w cwmpas arferol. Rhoddodd Cyngor Penaethiaid yr Heddlu Cenedlaethol enghreifftiau o'r heddlu'n llenwi bylchau yn y ddarpariaeth o wasanaethau eraill nad oeddent wedi'u hyfforddi'n iawn i'w gwneud.

| “ | Bu’n rhaid i’r heddlu fynd i le lle’r oedd rhai gwasanaethau’n tynnu’n ôl…gofynnwyd i ni ymweld â chartrefi o amgylch plant ac ymweliadau prawf. Roedd bylchau y gofynnwyd i’r heddlu eu llenwi.”

– Cyngor Cenedlaethol Prif Swyddogion yr Heddlu |

Dywedodd y Cyngor hefyd fod yr heddlu wedi ei chael hi'n anodd ymchwilio i droseddau a chasglu tystiolaeth a datganiadau tystion oherwydd eu bod yn gorfod cyfyngu ar gyswllt wyneb yn wyneb. Cafodd hyn effaith ar sut roeddent yn rheoli achosion ac mewn rhai achosion roedd yn golygu na allai achosion symud ymlaen oherwydd diffyg tystiolaeth.

| “ | Casglu tystiolaeth feddygol, ymweliadau â charchardai, mynd i fusnesau oedd ar gau, ceisio sicrhau tystiolaeth ac yn gyffredinol delio â phobl â Covid, roedd hynny i gyd yn gwneud casglu tystion yn anodd iawn.”

– Cyngor Cenedlaethol Prif Swyddogion yr Heddlu |

Esboniodd Cyngor Penaethiaid Cenedlaethol yr Heddlu a'r Grŵp Ymarferwyr Cymorth Cyfreithiol fod mwy o unigolion wedi cael eu rhyddhau ar amodau mechnïaeth cyn cyhuddo neu wedi cael eu rhyddhau dan ymchwiliad oherwydd mesurau cadw pellter cymdeithasol. Roedd hyn yn golygu bod ymchwiliadau wedi'u gohirio oherwydd anawsterau wrth gael penderfyniadau cyhuddo tra nad oedd yr amheuwyr yn y ddalfa, gyda rhai cyfnodau mechnïaeth yn dod i ben heb i gyhuddiadau gael eu dwyn.

Effaith ar weithwyr y sector cyfiawnder

Disgrifiodd cynrychiolydd Grŵp Ymarferwyr Cymorth Cyfreithiol sut roedd yn rhaid i'r heddlu a chyfreithwyr reoli eu risg eu hunain o ddal Covid-19 gan y rhai a gafodd eu harestio yn ystod y pandemig. Dywedasant fod rheoli'r risgiau hyn yn aml yn golygu peidio â chael cyswllt wyneb yn wyneb â'r rhai a gafodd eu harestio, gan arwain at oedi neu wybodaeth annigonol yn cael ei chasglu, gan rwystro cynnydd effeithiol achosion.

| “ | Fel ymarferydd mae'n rhaid i chi wneud penderfyniad ynghylch a fyddwch chi'n mynd i mewn i gell lle mae achosion o Covid wedi'u hadrodd, beth ydych chi'n ei wneud? Mae gennych chi ddyletswydd i'r cleient, ond rydych chi'n gwybod eich bod chi'n cymryd risg bersonol sylweddol.

– Grŵp Ymarferwyr Cymorth Cyfreithiol |

Roedd sefydliadau’r sector cyfiawnder yn ei chael hi’n anodd amddiffyn iechyd eu staff oherwydd nad oedd llawer yn cael eu hystyried yn weithwyr allweddol. Er enghraifft, teimlai cynrychiolydd Cymorth i Ddioddefwyr yr Alban, oherwydd nad oedd eu staff ar y gofrestr iechyd a gofal cymdeithasol yn yr Alban, nad oeddent yn gallu caffael Offer Diogelu Personol (PPE). Gadawodd hyn rai staff heb amddiffyniad wrth ddarparu cymorth yn bersonol. Pwysleisiasant hefyd nad oedd eu staff yn cael blaenoriaeth ar gyfer brechu, gan roi eu staff mewn mwy o berygl o’r feirws.

Yn yr un modd, dywedodd Cymdeithas Ymarferwyr Cyfraith Mewnfudo nad oedd yn glir pwy oedd yn weithiwr allweddol o fewn y system gyfiawnder. Roeddent o'r farn y dylid bod wedi ystyried unrhyw un a oedd yn paratoi achos cyfreithiol a fyddai'n cael ei gyflwyno yn y llys yn weithiwr allweddol, er mwyn caniatáu iddynt barhau â'u gwaith. Pan oedd cyfyngiadau'n golygu na allent, roedd hyn yn peri pryder i staff ac yn arwain at oedi wrth symud achosion ymlaen. Roedd staff yn ei chael hi'n anodd cael gafael ar fwndeli llys neu gyfarfod â chleientiaid yn bersonol i gasglu tystiolaeth angenrheidiol.

| “ | Nid oedd bargyfreithwyr yn gwybod yn ystod y pandemig a allent fynd i siambrau i gasglu bwndeli i adolygu'r dystiolaeth neu a oeddent yn weithwyr allweddol yn unig pan oeddent yn cael gwrandawiad. Roedd pobl yn ofni beicio i mewn i siambrau a chael eu dal a dweud wrthynt, 'Dydych chi ddim yn weithiwr allweddol heddiw, byddwch chi'n weithiwr allweddol ddydd Mercher pan fydd eich gwrandawiad apêl wedi'i restru ar ei gyfer'.”

– Cymdeithas Ymarferwyr Cyfraith Mewnfudo |

Gweithrediadau llys ac oedi

Bu oedi eang i achosion cyfreithiol a achoswyd gan nad oedd llysoedd yn eistedd yn bersonol ar ddechrau'r pandemig a'r symudiad dilynol i wrandawiadau o bell, yn enwedig mewn llysoedd sifil yng Nghymru a Lloegr. Andrew Dodsworth1 dywedodd fod parodrwydd i addasu i wrandawiadau o bell o ystyried pwysigrwydd gwneud hynny i ddioddefwyr a'r system gyfiawnder (yn ei brofiad ef yn eistedd yng Nghymru a Lloegr). Cynhaliwyd gwrandawiadau o bell i ddechrau trwy alwadau cynhadledd ffôn ac yna symudasant i gymysgedd o wrandawiadau ffôn a fideo. Dywedodd cynrychiolwyr fod y dull hwn wedi helpu i gadw llysoedd ar waith wrth reoli'r risgiau o Covid-19.

Rhoddodd Andrew Dodsworth enghreifftiau hefyd o lysoedd sifil yn defnyddio technoleg i addasu i wrandawiadau o bell, hyd yn oed ar gyfer yr adeiladau hynny nad oedd ganddynt fynediad rhyngrwyd Wi-Fi. Daeth atebion sain a gwe â rhai manteision i wrandawiadau llys, fel gallu rheoli cyfranogwyr aflonyddgar yn well trwy dawelu cyfranogwyr. Roedd gwrandawiadau o bell hefyd yn caniatáu rhestru mwy hyblyg, gan ei gwneud hi'n haws ac yn fwy effeithlon i archebu gwrandawiadau.

| “ | Fe wnaethon ni i gyd wneud pethau nad oedden ni’n meddwl y gallen ni eu gwneud. Pe byddech chi wedi gofyn i ni chwe wythnos cyn y pandemig a allem ni symud i bob gwrandawiad o bell, ni fyddai neb wedi dweud ie i hynny.”

– Andrew Dodsworth |

Fodd bynnag, nid oedd yn bosibl symud yr holl achosion llys ar-lein ledled y DU. Esboniodd cynrychiolwyr fod deddfwriaeth, mewn rhai achosion, yn ei gwneud yn ofynnol i fynychwyr fod yn bresennol yn bersonol. Mewn achosion eraill, roedd cwestiynau ynghylch moeseg darparu tystiolaeth fideo, yn enwedig mewn achosion o gam-drin domestig, gan ei bod yn anodd gwybod a oedd y troseddwr gyda'r dioddefwr ac yn rhoi pwysau arnynt tra roeddent yn rhoi tystiolaeth. Lle na ellid cynnal achosion llys ar-lein, arweiniodd yr anallu i'w cynnal yn bersonol at oedi.

| “ | Ar dystion sy'n rhoi tystiolaeth drwy fideo, cymerwch achos cam-drin domestig, ni allech chi byth fod yn siŵr nad oedd y troseddwr yn yr ystafell neu'n bygwth yr unigolyn hwnnw.”

– Cyngor Cenedlaethol Prif Swyddogion yr Heddlu |

Daeth rhai gwrandawiadau mewn llysoedd sifil yng Nghymru a Lloegr i ben i raddau helaeth yn gynnar yn y pandemig. Nododd Andrew Dodsworth, er enghraifft, fod achosion credyd defnyddwyr yswiriant traffig ffyrdd, llogi credyd ac yswiriant amddiffyn personol wedi cael eu hatal yn effeithiol oherwydd eu bod yn cael eu hystyried yn llai critigol nag achosion teulu. Dywedodd y Grŵp Ymarferwyr Cymorth Cyfreithiol fod achosion tai a throi allan yng Nghymru a Lloegr hefyd wedi cael eu gohirio oherwydd pryderon cymdeithasol ynghylch digartrefedd yn ystod y pandemig.

| “ | Mewn llysoedd teulu, os na chynhelir gwrandawiad mae canlyniadau hynny mor arwyddocaol i blant a dioddefwyr a rhieni…felly roedd yn rhaid i wrandawiadau llys ddigwydd.”

– Grŵp Ymarferwyr Cymorth Cyfreithiol |

Roedd oedi sylweddol hefyd ar gyfer gwrandawiadau llys troseddol. Yn ôl Cyngor Cenedlaethol Prif Swyddogion yr Heddlu, ar ddechrau'r pandemig dim ond achosion yn ymwneud â phobl a gedwid yn y ddalfa yn aros am achos llys y gallai llysoedd troseddol eu trin. Wrth i'r pandemig fynd rhagddo, symudwyd achosion i lwyfannau fideo, ar wahân i dreialon rheithgor. Fodd bynnag, roeddent yn teimlo bod amharodrwydd i symud i wrandawiadau o bell gyda dim ond nifer fach o lysoedd yn gwneud hynny. Roeddent hefyd yn ystyried y symudiad i sefydlu Llysoedd Nightingale dros dro2 roedd symud achosion llys ymlaen yn arbennig o araf. Roedd hyn yn golygu erbyn mis Mehefin 2021 bod ôl-groniad Llys y Goron yn 60,000 o achosion. Ar ben hynny, arweiniodd yr oedi i wrandawiadau llys troseddol at gynnydd sylweddol yn nifer y dioddefwyr a'r tystion a oedd yn cael eu cefnogi gan unedau Gofal Tystion yr heddlu. Nododd Cyngor Penaethiaid Cenedlaethol yr Heddlu fod cynnydd cyffredinol o 63% mewn llwythi achosion ar swyddogion sy'n gweithio mewn unedau Gofal Tystion, a gafodd effaith andwyol ar ddioddefwyr, tystion a staff yn yr unedau.

| “ | Dw i'n meddwl bod yna amharodrwydd i ddefnyddio rhywfaint o'r dechnoleg hon. Roedd yn araf…am bron yr holl amser Covid. Nid oedd yn ddeinamig yn y llys troseddol.”

– Cyngor Cenedlaethol Prif Swyddogion yr Heddlu |

Er bod gwrandawiadau o bell wedi caniatáu i rai achosion barhau a symleiddio rhai prosesau, dywedodd y Grŵp Ymarferwyr Cymorth Cyfreithiol ac Andrew Dodsworth ei bod hi'n anoddach i gynrychiolwyr cyfreithiol eiriol yn effeithiol ar-lein, yn enwedig i bartïon agored i niwed. Tynnodd Andrew Dodsworth sylw at y ffaith bod rhai achosion o bell yn heriol yn emosiynol, yn enwedig achosion sy'n ymwneud â grwpiau agored i niwed neu faterion sensitif. Dywedasant fod y diffyg cefnogaeth wyneb yn wyneb yn creu pellter emosiynol ac yn golygu nad oedd Barnwyr bob amser yn gallu gweld arwyddion iaith y corff, fel rhywun yn mynd yn ofidus neu'n emosiynol. Weithiau roedd hyn yn gadael pobl yn agored i niwed a heb gefnogaeth. Roeddent hefyd yn teimlo bod y diffyg cysylltiad wyneb yn wyneb yn golygu nad oedd gwrandawiadau o bell yn darparu'r un lefel o gefnogaeth, ac nad oeddent yn caniatáu i gyfreithwyr a chleientiaid feithrin perthnasoedd cryf.

Trafododd cynrychiolwyr sut roedd achosion llys yn cael eu rheoli'n wahanol ledled y DU. Roedd amharodrwydd canfyddedig yn yr Alban i symud achosion llys ar-lein a gyfrannodd at oedi yn y llys. O ganlyniad, roedd nifer fawr o unigolion ar fechnïaeth neu yn y ddalfa wrth iddynt aros am achos llys, yn enwedig ar gyfer achosion mwy difrifol a gwrandawiadau yn cynnwys sawl diffynnydd.

Esboniodd Cymorth i Ddioddefwyr yr Alban fod achosion llys sifil yn yr Alban yn gallu mynd rhagddynt ar-lein ond eu bod yn llai sicr ynghylch sut roedd llysoedd teulu yn addasu. Dywedasant, ar gyfer achosion troseddol, fod treialon rheithgor wedi'u hatal o fis Mawrth 2020 a bod pob treial troseddol heblaw am rai hanfodol wedi'i ohirio. Er bod rhai treialon wedi dechrau digwydd eto ym mis Mehefin 2020, roedd llysoedd troseddol yn gweithredu ar gapasiti llawer llai. Creodd hyn ôl-groniad o achosion a barhaodd i gynyddu yn 2021.3 I geisio lleihau'r ôl-groniadau hyn, cynhaliwyd cynllun peilot ar gyfer gwrandawiadau o bell. Fodd bynnag, dim ond 10 sesiwn o bell a gynhaliwyd ac ni arweiniodd hyn at welliant yn yr ôl-groniad. Nododd cynrychiolwyr Cymorth i Ddioddefwyr yr Alban hefyd fod system dystiolaeth wedi'i recordio ymlaen llaw eisoes wedi'i chyflwyno yn 2017, a oedd yn caniatáu clywed tystiolaeth o bell. Dywedasant fod gallu defnyddio'r system hon wedi ei gwneud hi'n haws cynnal achosion yn ystod y pandemig, ond ei bod hi'n dal yn anodd gweithredu cadw pellter cymdeithasol os nad oedd ystafelloedd llys yn ddigon mawr. Roedd angen o hyd i gyfreithwyr amddiffyn fynychu'n bersonol i gynnal croesholi. Teimlai Cymorth i Ddioddefwyr yr Alban fod yr oedi yn yr Alban hefyd wedi'i ddylanwadu gan boblogaeth heneiddio'r barnwyr, y bu'n ofynnol i lawer ohonynt amddiffyn eu hunain yn ystod y pandemig. Lleihaodd hyn y capasiti yn sylweddol.

Gweithredodd yr Alban ohiriad gweinyddol 90 diwrnod a oedd yn caniatáu atal achos cyfreithiol dros dro er mwyn cwblhau tasgau gweinyddol neu i alluogi partïon i baratoi. Gellid defnyddio'r gohiriad gweinyddol 90 diwrnod ar gyfer achos llys sawl gwaith. Gohiriwyd llawer o achosion sawl gwaith a oedd yn lleihau'r hyder y byddai achosion yn digwydd ac yn gadael pobl mewn patrwm aros, yn ansicr a ddylent baratoi ar gyfer achos.

Gwaethygodd y pandemig lwythi gwaith gweithwyr proffesiynol cyfreithiol ac fe'i disgrifiwyd fel un a gafodd effaith negyddol ar eu hiechyd meddwl. Bu'n rhaid i weithwyr proffesiynol cyfreithiol drawsnewid i wahanol ffyrdd o weithio, gan gynnwys newidiadau i brosesau casglu tystiolaeth a gwybodaeth a gwrandawiadau o bell. Esboniodd y Grŵp Ymarferwyr Cymorth Cyfreithiol fod y newid cyflym yn golygu bod yn rhaid i weithwyr proffesiynol cyfreithiol addasu'n gyflym a bod hyn yn achosi straen sylweddol. Roedd y cyfyngiadau ar gyswllt wyneb yn wyneb hefyd yn llesteirio eu gallu i gefnogi cleientiaid yn effeithiol gan na allent gyfarfod wyneb yn wyneb a meithrin perthynas. Nid oedd unrhyw adnoddau ychwanegol gan y llywodraeth i addasu adeiladau swyddfa i gefnogi cadw pellter cymdeithasol fel y gallai cleientiaid gyfarfod â'u cynrychiolwyr cyfreithiol neu i sicrhau bod yr ystafelloedd yn cael eu glanhau rhwng cysylltiadau cleientiaid. Roedd hyn yn golygu na allent fod yn sicr eu bod yn gweithredu mewn ffordd ddiogel o ran Covid-19.

| “ | Roedd yn glodwiw bod datblygiad cyflym i symud i wrandawiadau dros y ffôn ac o bell ond yr hyn a dueddodd i'w wneud oedd creu pwysau enfawr ar ymarferwyr i hwyluso mynediad cleientiaid, yn hytrach na'r llysoedd yn gwneud hynny oherwydd na allent. Felly, roedd yn rhaid i ymarferwyr addasu'n gyflym iawn, heb unrhyw gyllid ychwanegol gan y llywodraeth, addasu eu mannau swyddfa fel y gallent gydymffurfio â chyfyngiadau Covid-19 a chael eu cleientiaid yn y swyddfa gyda nhw.”

– Grŵp Ymarferwyr Cymorth Cyfreithiol |

Trafododd cynrychiolydd Cymorth i Ddioddefwyr yr Alban hefyd sut roedd system y llysoedd yn dibynnu ar wirfoddolwyr, llawer ohonynt yn hŷn, i gefnogi dioddefwyr yn y llys. Fel arfer, roedd y gwirfoddolwyr hyn yn cynnig cymorth ymarferol ac emosiynol ac yn darparu gwybodaeth i alluogi unigolion i ddeall proses y llys. Rhoddodd nifer fawr o wirfoddolwyr y gorau i helpu yn ystod y pandemig am resymau iechyd, megis yr angen i warchod eu hunain a phryderon ynghylch sut roedd llysoedd yn cael eu rheoli i amddiffyn pobl rhag dal Covid-19. Yn ôl cynrychiolydd Cymorth i Ddioddefwyr yr Alban, roedd colli gwirfoddolwyr yn ei gwneud hi'n anoddach rheoli llysoedd yn effeithiol gan nad oedd y gefnogaeth arferol i'r rhai oedd yn llywio'r system gyfreithiol ar gael mwyach.

| “ | Mae'n boblogaeth o bobl sy'n heneiddio ac yn golled wirioneddol i'r sefydliad, [collon ni] 75% o'n gwirfoddolwyr rhwng Mawrth 2020 ac Ebrill 2020. Ac yn bennaf ni ddychwelon nhw i'r sefydliad.”

– Cymorth i Ddioddefwyr yr Alban |

Wrth i'r pandemig leddfu, bu symudiad yn ôl i wrandawiadau wyneb yn wyneb ond gyda phellhau cymdeithasol ar waith. Disgrifiodd y Grŵp Ymarferwyr Cymorth Cyfreithiol sut y cyfrannodd amrywiol ffactorau at oedi pellach, gan gynnwys mesurau cadw pellter cymdeithasol mewn llysoedd, dibyniaeth ar dechnoleg nad oedd bob amser yn gweithio, cyfyngiadau ar gapasiti ystafelloedd llys, a phrofion Covid-19 positif. Nododd Andrew Dodsworth fod rhai gweithwyr proffesiynol yn amharod i fynd yn ôl i wrandawiadau llys wyneb yn wyneb. I rai roedd hyn yn seiliedig ar bryderon dilys am eu hiechyd eu hunain, ond roedd ymddangos o bell hefyd yn cynnig i eiriolwyr y gallu i gymryd achosion mewn sawl canolfan llys ar yr un diwrnod wrth weithio o gartref.

Disgrifiodd Cymorth i Ddioddefwyr yr Alban sut y gwnaeth llysoedd yr Alban fabwysiadu dull gwahanol mewn ymgais i leihau oedi a gwaith ôl-groniadol yn y llysoedd. Dywedwyd bod hyn yn cynnwys ailgyflunio model y rheithgor, fel y byddai rheithgorau yn arsylwi'r achos llys o bell o sinemâu, gan ganiatáu mwy o bellter cymdeithasol yn ystafell y llys. Gwnaed ymdrechion hefyd i ailddosbarthu achosion ymhlith llysoedd mewn ardaloedd mwy gwledig yn yr Alban, nad oeddent mor brysur. Fodd bynnag, siaradodd cynrychiolydd Cymorth i Ddioddefwyr yr Alban am y materion sy'n codi o hyn, gan gynnwys diffyg ymgynghori, diffyg cefnogaeth yn y llys a chynllunio ymlaen llaw annigonol i'w galluogi i ddarparu cymorth cefnogi dioddefwyr yn y lleoliadau hyn, gan olygu na allai rhai achosion fynd yn eu blaen.

| “ | Roedd yn dros dro, gan ddefnyddio sinemâu oedd yn wag. Costiodd filiynau i'w hailwneud i'w helpu i hwyluso'r sefyllfa gyfan hon. Yna daethom allan o'r cyfnod clo a dechreuodd pobl fynd yn ôl i'r sinema ac roedd yn rhaid iddynt ddod o hyd i ateb newydd.”

– Cymorth i Ddioddefwyr yr Alban |

Effaith ar ddioddefwyr troseddau

Mynediad at gefnogaeth

Gwnaeth y pandemig hi'n anoddach i ddioddefwyr troseddau gael mynediad at gymorth gan eu teuluoedd, ffrindiau a sefydliadau. Roedd ganddynt fynediad cyfyngedig at wasanaethau cymunedol a chyfreithiol fel canolfannau cyfreithiol a chyfreithwyr oherwydd bod y gwasanaethau hyn wedi'u lleihau neu wedi'u symud ar-lein. Teimlai cynrychiolwyr fod hyn yn creu rhwystrau sylweddol i ddioddefwyr sy'n ceisio cyngor cyfreithiol a chymorth emosiynol ac ymarferol hanfodol.

| “ | Mae pobl yn mynd i gael cyngor cyfreithiol gan gyfreithwyr, canolfannau cyfraith, Canolfannau Cyngor ar Bopeth, ffrindiau, teulu, offeiriaid, athrawon, meddygon, ond yn ystod y pandemig os na allwch weld unrhyw bobl, ni allwch gael y cyngor ffurfiol hwnnw, yna i ble rydych chi'n mynd?”

– Grŵp Ymarferwyr Cymorth Cyfreithiol |

Disgrifiwyd y diffyg cefnogaeth hwn fel un sy'n effeithio'n anghymesur ar unigolion sy'n wynebu rhwystrau iaith wrth lywio'r system gyfiawnder. Nododd Medical Justice fod eu harfer arferol o ymgysylltu â rhwydweithiau teuluol fel cyfieithwyr wedi'i amharu gan fesurau cadw pellter cymdeithasol. Roedd hyn yn golygu bod gan lawer o ddioddefwyr troseddau lai o wybodaeth yn eu hiaith eu hunain ac yn deall llai am yr hyn oedd yn digwydd gyda'u hachos.

Tynnodd cynrychiolydd Cymorth i Ddioddefwyr sylw hefyd at rwystrau penodol i gael mynediad at gyfiawnder y mae dioddefwyr â chyflyrau corfforol neu anableddau, a phobl hŷn, yn eu hwynebu oherwydd eu hofnau ynghylch dal Covid-19. Dywedasant eu bod yn amharod i fynd i'r llys yn bersonol a bod hyn yn eu gwneud yn llai tebygol o ymgysylltu â'r system gyfiawnder.

Canfu Cymorth i Ddioddefwyr yr Alban eu bod yn cefnogi cleientiaid ag anghenion mwy cymhleth oherwydd effaith gyffredinol y pandemig ar ddioddefwyr. Dywedasant fod gwneud hynny wedi'i wneud yn anoddach oherwydd nad oeddent wedi'u cynnwys yn y cynllunio ar gyfer yr ymateb i'r pandemig ac nad oeddent yn gwybod pa newidiadau oedd yn cael eu gwneud na sut i helpu eu cleientiaid orau.

Cytunodd y cynrychiolwyr fod oedi yn y llys yn ystod y pandemig wedi tanseilio hyder dioddefwyr y byddent yn cyflawni canlyniad amserol. Tynnodd y Grŵp Ymarferwyr Cymorth Cyfreithiol sylw at sut roedd oedi i achosion llys yn golygu bod nifer o achosion heb eu datrys neu heb eu cychwyn. Roedd ymarferwyr cyfreithiol yn ei chael hi'n anodd darparu amserlenni realistig i ddioddefwyr a thystion. Nododd Cyngor Penaethiaid yr Heddlu Cenedlaethol fod pobl wedi cael gwybod mewn rhai achosion na fyddai eu hachos yn cael ei glywed am 2-3 blynedd a oedd yn ei gwneud hi'n anodd iddynt fyw eu bywydau gan eu bod mewn 'cyflwr o limbo'. Dywedasant fod yr oedi hyn wedi digalonni cyfranogiad yn y system gyfiawnder ac wedi achosi i lawer dynnu'n ôl o'r broses gyfreithiol.

Mynediad at dechnoleg

Roedd llawer o bobl yn wynebu rhwystrau technolegol i gael mynediad at gyfiawnder yn ystod y pandemig. Yn aml, nid oedd dioddefwyr yn gyfarwydd â'r prosesau ar-lein, roedd ganddynt fynediad cyfyngedig at y dechnoleg ofynnol neu nid oedd ganddynt gysylltiad rhyngrwyd digon dibynadwy i gymryd rhan mewn achosion ar-lein. Dywedodd cynrychiolwyr fod hyn yn ei gwneud hi bron yn amhosibl i'r dioddefwyr mwyaf agored i niwed gael mynediad at gyfiawnder, gan gynnwys y rhai a gefnogir gan gymorth cyfreithiol. Yn aml, roedd yn rhaid i aelodau'r Grŵp Ymarferwyr Cymorth Cyfreithiol fenthyg technoleg i gleientiaid neu dalu am ddata ffôn, ond nid oedd unrhyw ffordd iddynt hawlio'r costau hynny yn ôl. Teimlai cynrychiolwyr fod y system gyfiawnder yn tybio bod gan bobl fynediad at dechnoleg pan nad oedd hynny'n wir.

| “ | Nid oedd gan [y partïon] ffôn sylfaenol na digon o ddata i gymryd rhan mewn gwrandawiadau, heb sôn am liniadur na thabled. Roedd angen yr un adnodd cyfyngedig hwnnw hefyd i ganiatáu i'w plant gael mynediad at addysg. Gwnaeth Barnwyr Dosbarth y pwynt hwn ond cymerodd amser iddo gael ei dderbyn. Mae wyneb glo'r system cyfiawnder teuluol yn fyd gwahanol iawn i'r achosion masnachol gwerth miliynau o bunnoedd lle gall partïon symud ar-lein yn llawer haws.”

– Andrew Dodsworth |

Fodd bynnag, nododd cynrychiolwyr fod rhai dioddefwyr yn ffafrio’r symudiad i achosion llys o bell. Cyfeiriodd Cymorth i Ddioddefwyr yr Alban at adborth cadarnhaol o gynllun peilot ar gyfer gwrandawiadau o bell mewn achosion troseddol a oedd yn dangos bod gwrandawiadau ar-lein yn dileu’r ofn o weld y diffynnydd yn bersonol yn y llys, a oedd yn gwneud i’r dioddefwr deimlo’n fwy diogel ac yn fwy abl i gymryd rhan ym mhroses y llys.

Effaith ar garchardai a charcharorion

Esboniodd yr Ymddiriedolaeth Diwygio Carchardai fod gostyngiad cychwynnol ym mhoblogaeth y carchardai yn gynnar yn y pandemig oherwydd oedi achos llys, gan arwain at lai o garcharorion newydd. Fodd bynnag, wrth i'r pandemig fynd rhagddo, cynyddodd oedi yn y llys nifer y carcharorion a gedwid yn y ddalfa.4 a lleihad mewn capasiti carchardai. Dywedodd cynrychiolydd Howard League, unwaith y byddai cyfyngiadau’r pandemig wedi llacio, fod y problemau capasiti a wynebwyd gan garchardai cyn y pandemig wedi gwaethygu. Roedd carchardai’n wynebu problemau gyda gorlenwi a gorfodi cadw pellter cymdeithasol oherwydd ailgychwyn treialon a’r cynnydd canlyniadol ym mhoblogaeth y carchardai. Dywedasant fod hyn yn broblem benodol yn Lloegr a rhai rhannau o’r Alban.

Er mwyn lleihau nifer y carcharorion, cyflwynwyd polisi ym mis Ebrill 2020 i ryddhau carcharorion ar drwydded dros dro os oedd ganddynt ddau fis neu lai o'u dedfryd i'w gwasanaethu o hyd. Fodd bynnag, daeth y cynllun hwn i ben ym mis Awst 2020 oherwydd problemau gweinyddol. Nododd Cynghrair Howard mai dim ond 262 o bobl a ryddhawyd yn gynnar erbyn diwedd y cynllun. Dywedasant, o ganlyniad i'r penderfyniad i atal y cynllun, na allai carchardai weithredu'n ddiogel o dan ganllawiau Covid-19 ac roeddent yn agored i orlenwi unwaith y byddai mesurau pandemig yn cael eu llacio. Roeddent o'r farn y byddai rhyddhau mwy o garcharorion yn gynnar wedi caniatáu i garchardai weithredu mewn ffordd lai cyfyngol yn ystod y cyfnod clo a byddai wedi ei gwneud hi'n haws i garchardai ddychwelyd i gyfundrefnau mwy agored ar ôl y pandemig.

| “ | "Mae'r penderfyniad cynnar hwnnw i beidio â rhyddhau pobl, i beidio â chreu'r lle pen, rwy'n credu ei fframio mewn gwersi a ddysgwyd, penderfyniad tymor byr er hwylustod gwleidyddol mewn cyfnod o argyfwng cenedlaethol yn gamgymeriad, mae ganddo oblygiadau hirdymor." DYFYNIAD TESTUN

– Cynghrair Howard |

Gweithrediadau carchar

Trafododd cynrychiolwyr effaith y newidiadau a gyflwynwyd mewn carchardai i reoli risgiau Covid-19. Er mwyn atal lledaeniad Covid-19 mewn carchardai, cyflwynwyd system o'r enw 'cohortio'. Cafodd unigolion â symptomau Covid-19 eu grwpio mewn cohort gyda charcharorion symptomatig eraill mewn 'asgell ynysu'. Esboniodd Medical Justice fod hyn yn ymarferol yn aml yn golygu bod unigolion symptomatig yn cael eu hynysu am gyfnod hirach, oherwydd pe bai achos arall yn y cohort byddai'n rhaid i'r cyfnod ynysu barhau nes bod yr holl achosion wedi'u clirio.

Cafodd y rhan fwyaf o weithgareddau eu hatal, gan gynnwys atal addysg carchar, rhaglenni ymddygiad troseddwyr diangen, ymweliadau teulu a throsglwyddo carcharorion. Dywedasant fod hyn yn golygu bod carcharorion yn cael eu cloi yn eu celloedd am tua 23 awr y dydd. Os oedd gan garcharorion symptomau Covid-19, roeddent yn cael eu rhoi mewn cwarantîn mewn adain ynysu ar wahân. Roedd cyfraddau trosglwyddo carchar yn cael eu monitro ac os oedd cyfraddau trosglwyddo yn gostwng, roedd cyfyngiadau Covid-19 yn cael eu llacio. Fodd bynnag, dywedasant fod y llacio hwn yn aml yn cymryd amser a byddai'n cael ei wrthdroi'n gyflym pe bai achos arall o Covid-19.

Symudwyd gwrandawiadau parôl ar-lein ac roedd hyn wedi bod yn llwyddiannus yn gyffredinol. Fodd bynnag, eglurodd yr Ymddiriedolaeth Diwygio Carchardai, oherwydd atal gweithgareddau, nad oedd gan garcharorion fynediad at y rhaglenni ymddygiad troseddol arferol yr oeddent yn dibynnu arnynt i ddangos llai o risg at ddiben ceisiadau parôl. Yn ogystal, dywedodd cynrychiolwyr fod trosglwyddiadau carchar wedi'u hatal yn ystod y pandemig, a oedd yn golygu na allai carcharorion symud i garchardai â gwell mynediad at gefnogaeth neu weithgareddau yr oedd eu hangen arnynt i gefnogi ceisiadau parôl. Dywedodd yr Ymddiriedolaeth Diwygio Carchardai y gallai hyn fod wedi atal dilyniant carcharorion tuag at gael parôl.

Roedd cyfathrebu rhwng carcharorion a rheolwyr troseddwyr hefyd yn gyfyngedig oherwydd na allent gynnal cyfarfodydd wyneb yn wyneb. Mae rheolwyr troseddwyr yn gyfrifol am reoli adsefydlu carcharorion ac asesu eu risg i'r cyhoedd a'r tebygolrwydd o aildroseddu. Yn ôl yr Ymddiriedolaeth Diwygio Carchardai, mae'r berthynas hon yn hanfodol ar gyfer gosod nodau a chreu ymyriadau wedi'u teilwra i anghenion carcharorion, gan helpu i leihau eu risg o aildroseddu. O ganlyniad, gostyngwyd cyfleoedd i garcharorion sicrhau rhyddhad cynnar, gan ychwanegu mwy o straen at weithrediadau a chapasiti carchardai.

| “ | Daeth cyfathrebu rhwng carcharorion a rheolwyr troseddwyr yn anodd. Mae'r berthynas honno'n bwysig o ran cynllunio dedfrydau. Heb hynny, efallai na fyddwch yn cael eich cyfeirio at y gweithgaredd sydd angen i chi ei wneud.”

– Ymddiriedolaeth Diwygio Carchardai |

Cafodd yr ofn o drosglwyddo Covid-19 a newidiadau i weithrediadau carchardai yn ystod y pandemig ganlyniadau negyddol dwys i garcharorion. Esboniodd yr Inquest fod carcharorion yn boblogaeth agored i niwed, gyda chyfraddau uwch o broblemau iechyd meddwl na'r boblogaeth gyffredinol. Trafodasant sut y cynyddodd y cyfyngiadau ar gefnogaeth i garcharorion a'r cynnydd mewn caethiwed unigol bryder, iselder, hunan-niweidio, hunanladdiad a marwolaethau anochel. Roedd carcharorion yn ofni'r risg o drosglwyddo a achosir gan staff yn dod i mewn ac allan o garchardai a heb wisgo PPE. Roedd cynrychiolwyr o'r farn bod hyn yn gwaethygu pryder ymhlith carcharorion ac yn atgyfnerthu eu canfyddiad nad oedd yn bwysig eu hamddiffyn rhag Covid-19.

| “ | Roedd teimlad bod carcharorion yn llai pwysig o ran atal eu hamlygiad. P'un a yw hynny'n wir ai peidio, dyna oedd y canfyddiad.”

– Ymddiriedolaeth Diwygio Carchardai |

Yn fwy cyffredinol, roedd carcharorion yn aml yn profi teimladau o anniddigrwydd, dicter a rhwystredigaeth. Dywedodd cynrychiolwyr fod y diffyg gofal canfyddedig i'r rhai mewn carchardai yn ystod y pandemig yn atgyfnerthu'r farn ymhlith carcharorion eu bod yn llai haeddiannol o driniaeth deg na'r rhai mewn cymdeithas ehangach.

| “ | Mae pobl mewn carchardai ymhlith y bobl fwyaf ymylol a dan anfantais yn y gymdeithas, felly mae'n rhaid i chi gael hynny fel man cychwyn.”

– Cwest |

Tynnodd yr Ymddiriedolaeth Diwygio Carchardai sylw at yr effaith gronnus ar garcharorion o gael eu cyfyngu i'w celloedd am hyd at 23 awr y dydd dros gyfnodau hir, a'r niwed canlyniadol i'w hiechyd meddwl. Yn yr amser cyfyngedig y caniatawyd i garcharorion adael eu celloedd, dywedodd y cynrychiolydd Cyfiawnder Meddygol eu bod yn aml yn gorfod penderfynu rhwng cael galwad ffôn, cael cawod neu gael awyr iach. Er gwaethaf y canlyniadau negyddol hyn o'r amser cynyddol mewn carchar, nododd cynrychiolwyr mai un fantais oedd gostyngiad yn lefelau trais.

| “ | Roedd llai o drais rhwng carcharorion a staff a llai o drais rhwng carcharorion a staff, ac rwy'n credu bod hynny'n ganlyniad anfwriadol o'r unigedd parhaus a'r amser mewn celloedd. Roedd yn beth da bod llai o drais ond y peth drwg oedd bod gan bobl fynediad cyfyngedig iawn at eu ffrindiau a'u teulu. Cododd hunan-niweidio ac iechyd meddwl yn sydyn oherwydd cyfnodau hir o unigedd heb fawr o weithgarwch ystyrlon na phwrpasol.”

– Mecanwaith Ataliol Cenedlaethol |

Disgrifiodd Cyngor Cenedlaethol Prif Swyddogion yr Heddlu ymhellach sut yr oedd carcharorion yn profi mynediad cyfyngedig neu ddim mynediad o gwbl at gawodydd neu ymarfer corff ac yn cael eu gorfodi i droethi a baeddu yn eu celloedd heb fynediad at lanweithyddion dwylo, a'r effaith negyddol a gafodd hyn ar eu hiechyd meddwl.

Ymhellach, pan ddaeth ymweliadau teuluol i ben, collodd carcharorion eu prif gysylltiad â'u hanwyliaid a'u rhwydweithiau a'u cymunedau y tu allan i'r carchar. Arweiniodd hyn at ymdeimlad cynyddol o unigedd, ansicrwydd ac ofn ymhlith carcharorion.

| “ | Nid oedd gan garcharorion y gallu i wneud y pethau y byddem yn cynghori ein cleifion i'w gwneud, cysylltu â rhywun cefnogol, mynd am dro, cael rhywfaint o awyr iach. Mae'r rhain yn hanfodol i'n hiechyd meddwl ni i gyd, roedd hynny i gyd wedi mynd, sefyllfa sydd mor niweidiol ag y gallech chi feddwl amdani, yn enwedig i'r grŵp agored i niwed hwn. Dwi ddim yn credu nad oes unrhyw ffordd o gyfiawnhau hynny'n feddygol. Roedd yn gwbl groes i drin pobl yn y ffordd honno. Mae carcharorion yn dal i deimlo canlyniadau hynny.”

– Cyfiawnder Meddygol |

Trafododd cynrychiolwyr yr effaith ar garcharorion a brofodd farwolaeth aelodau o'u teulu yn ystod y pandemig. Esboniodd y cwest nad oedd carcharorion wedi cael cyfle i ffarwelio ag aelodau o'u teulu a oedd yn marw na mynychu gwasanaethau angladd, gan ddwysáu eu hofnau ynghylch effaith y pandemig ar gymdeithas ehangach ac ar eu ffrindiau a'u teulu. Yn yr un modd, cynyddodd y pandemig a'r risg o drosglwyddo Covid-19 mewn carchardai bryderon teuluoedd carcharorion ynghylch diogelwch ac iechyd eu hanwyliaid.

Mynediad at ofal iechyd

Yn ôl cynrychiolwyr, roedd mynediad carcharorion at ofal iechyd wedi'i leihau'n sylweddol yn ystod y pandemig, gan waethygu effeithiau'r newidiadau i gyfundrefnau carchardai ar iechyd corfforol. Roedd y cwest o'r farn bod y pandemig wedi gwaethygu problem hirhoedlog mewn carchardai o ran diystyru problemau iechyd a chael mynediad cyfyngedig at ofal iechyd gan garcharorion. Ymhellach, roedd rhai carcharorion yn amharod i ddatgelu symptomau Covid-19 er mwyn osgoi'r cyfnod o ynysu estynedig a oedd yn rhan o'r system garfanu ac, o ganlyniad, efallai na fyddent wedi derbyn y driniaeth yr oedd ei hangen arnynt.

Esboniodd Medical Justice fod unigolion â chyflyrau cronig fel diabetes ac asthma yn methu apwyntiadau allanol arferol. Roedd carcharorion wedi'u cyfyngu am 23 awr y dydd ac yn cael ymweliadau clinigwyr yn llai aml, ac roedd hyn i gyd yn effeithio'n negyddol ar eu hiechyd. Darparodd y Mecanwaith Ataliol Cenedlaethol enghraifft o un carchar lle dim ond ddwywaith yr ymwelwyd â charcharorion â Covid-19 gan staff gofal iechyd yn ystod cyfnod ynysu o 14 diwrnod.

| “ | Ar gyfer cyflyrau meddygol eraill, gwelsom bobl yn colli apwyntiadau, diffyg trafnidiaeth, diffyg staff gofal i'w hebrwng ac, wedi'i waethygu gan yr amseroedd ychwanegol ar y GIG, gwelsom afiechydon corfforol, canserau, pobl yn colli eu dilyniannau cleifion allanol.”

– Cyfiawnder Meddygol |

Ychwanegodd Medical Justice fod y pandemig wedi achosi oedi wrth drosglwyddo carcharorion oedd yn wael iawn ac sydd angen cymorth iechyd meddwl neu driniaeth feddygol i ysbytai. Tynnasant sylw at sut roedd y sefyllfaoedd hyn yn gwneud i garcharorion oedd yn rhannu celloedd â charcharorion oedd yn wael deimlo'n anghyfforddus ac yn bryderus am iechyd eu cyd-gell.

| “ | Ni chafodd pobl eu trosglwyddo nes ei bod hi'n rhy hwyr. Ni chafodd ambiwlansys eu galw mewn modd amserol; ni chafodd difrifoldeb y sefyllfa ei gydnabod.”

– Cyfiawnder Meddygol |

Bu symudiad tuag at ddarparu asesiadau meddygol o bell i garcharorion yn ystod y pandemig yn ôl Medical Justice. Er nad oeddent yn lle ymgynghoriadau wyneb yn wyneb, disgrifiwyd yr apwyntiadau o bell fel rhai cyfleus ac effeithlon. Fodd bynnag, roedd rhwystrau sylweddol i gael mynediad at ofal iechyd yn parhau i'r rhai nad oedd Saesneg yn iaith gyntaf iddynt gan fod angen dehonglydd arnynt. Roedd carcharorion â phroblemau iechyd meddwl nad oedd ganddynt y gallu meddyliol i ymgysylltu â'u gofal hefyd yn cael trafferth gyda'r newid i apwyntiadau o bell.

Roedd atgyfeiriadau arbenigol ar gyfer cymorth iechyd meddwl yn gyfyngedig neu'n cael eu gohirio, gydag asesiadau risg critigol ac apwyntiadau heb gael eu cynnal. Mewn rhai achosion, dywedodd Medical Justice fod carcharorion, er mwyn trin straen wedi trawma, yn cael 'pecyn trawma seicolegol' a oedd yn cynnig rhai awgrymiadau hunanofal. Fodd bynnag, dywedasant nad oedd llawer o'r awgrymiadau'n bosibl tra'u bod yn y ddalfa ac yn gyffredinol gwelwyd bod y pecynnau'n annigonol o ran diwallu eu hanghenion. Nododd cynrychiolydd y Cwest sut y methodd carchardai eraill â rhoi asesiadau risg ar waith ar gyfer carcharorion a allai fod wedi bod yn hunanladdol yn ystod y pandemig. Roeddent yn credu bod hyn oherwydd nad oedd ymarferwyr iechyd meddwl yn gallu ymweld â charchardai ar y pryd ac na allent nodi bod carcharorion o bosibl yn profi meddyliau hunanladdol.

Mynediad at dechnoleg

Dywedodd cynrychiolwyr fod mynediad at dechnoleg hyd yn oed yn bwysicach ar gyfer lles carcharorion yn ystod y pandemig nag yr oedd wedi bod o'r blaen, gan ganiatáu cyswllt teuluol a mynediad o bell at wasanaethau. Fodd bynnag, nid oedd mynediad at dechnoleg yn gyfartal ar draws carchardai, gan mai dim ond tua hanner y celloedd carchar oedd â ffonau yn ôl cynrychiolwyr. Yn gynnar yn y pandemig, mewn carchardai lle nad oedd gan garcharorion ffonau yn y gell, dosbarthodd y llywodraeth 900 o setiau llaw ffôn diogel. Er bod cynrychiolwyr yn gweld hyn fel datblygiad cadarnhaol, nodwyd ganddynt fod nifer y setiau llaw yn gymharol fach ar ôl iddynt gael eu dosbarthu ar draws 60 o garchardai. Mewn achosion eraill, rhoddasant enghreifftiau o garchardai lle efallai mai dim ond un ffôn sydd ar yr adain, gan arwain at gystadleuaeth ymhlith carcharorion am fynediad.

| “ | Gwnaeth y mynediad gwahaniaethol hwnnw at ddarn sylfaenol iawn o dechnoleg wahaniaeth enfawr i unigedd pobl pan oeddent dan glo. Gwnaeth wahaniaeth hefyd i fynediad at wasanaethau – gellid gwneud telefeddygaeth dros y ffôn. Os oes gennych ffôn yn eich cell, mae gennych chi rywfaint o breifatrwydd, yn enwedig os nad ydych chi'n rhannu. Os ydych chi'n ceisio ei wneud ar ffôn asgell gyda phobl o'ch cwmpas, ni fydd gennych chi'r cyfrinachedd y byddech chi ei eisiau mewn archwiliad meddygol.

– Ymddiriedolaeth Diwygio Carchardai |

Tynnodd cynrychiolwyr sylw at yr effaith gadarnhaol o gyflwyno ffonau a thechnoleg fideo-gynadledda mewn carchardai gan ei fod yn caniatáu i garcharorion gynnal cysylltiad â'u teuluoedd. Mewn un carchar, dywedodd Cynghrair Howard fod carcharorion yn cael eu hannog i ddarllen straeon amser gwely i'w plant. Mewn achosion eraill, rhoddwyd credyd ffôn ychwanegol i garcharorion fel y gallent fforddio ffonio adref yn amlach. Er nad ystyriwyd ei fod yn ddewis digonol yn lle ymweliadau personol, roedd cynrychiolwyr yn credu, lle'r oedd y technolegau hyn ar gael, eu bod yn helpu i gynnal cysylltiadau rhwng carcharorion a'u teuluoedd.

| “ | Pan oedd y mynediad hwnnw at deuluoedd yn gweithio, fe weithiodd mewn gwirionedd. Cafodd effaith wirioneddol ar lesiant pobl unwaith y gallent weld aelodau eu teulu a siarad â'u haelodau teulu.”

– Mecanwaith Ataliol Cenedlaethol |

Craffu

Esboniodd cynrychiolydd y Mecanwaith Ataliol Cenedlaethol sut roedd mynediad i sefydliadau allanol, fel Byrddau Monitro Annibynnol (IMBs) sy'n monitro triniaeth a lles carcharorion, yn gyfyngedig yn ystod y pandemig, gan leihau goruchwyliaeth allanol. Yn lle hynny, roedd yn rhaid i IMBs ddibynnu ar alwadau gan garcharorion i rif ffôn am ddim i roi gwybod am broblemau. Esboniodd y Mecanwaith Ataliol Cenedlaethol fod ymweliadau craffu byr trwy Arolygiaeth Carchardai EM (HMIP) wedi'u rhoi ar waith wrth i'r pandemig barhau. Roedd y rhain yn cynnwys rhai arolygiadau personol, wedi'u hategu gan arolygiadau o bell. Dywedasant fod hyn yn golygu bod rhywfaint o oruchwyliaeth o'r carchar, ond roedd amlder a hyd llai'r ymweliadau hyn yn golygu nad oedd carchardai'n cael eu gwerthuso'n gynhwysfawr.

Effaith hirdymor ar y system gyfiawnder

Oedi a'r effaith ar hyder y cyhoedd

Roedd consensws eang ymhlith cynrychiolwyr nad oedd gan y system llysoedd y gwydnwch i ymdopi â phandemig. Dywedasant fod y pandemig wedi gwaethygu problemau hirhoedlog gyda llwythi achosion mawr ac ôl-groniadau llys.

| “ | Dw i ddim yn meddwl bod y systemau’n wydn o gwbl. Mae’r pandemig newydd ddatgelu hynny. Roedden nhw wedi’u gwagio i’r fath raddau…roedd y gallu i hyblygu mewn ffordd ystwyth yn gyfyngedig iawn.”

– Andrew Dodsworth |

Er enghraifft, dywedodd cynrychiolydd Cymorth i Ddioddefwyr yr Alban fod 2,000 o achosion llys uchel yn yr Alban yn dal i aros i gael eu clywed. O ystyried bod y rhain yn ymwneud â throseddau difrifol ac yn achosion blaenoriaeth uchel, roeddent o'r farn bod yr oediadau hyn yn dangos yr effaith hirdymor ar y system a mynediad dioddefwyr at gyfiawnder.

Disgrifiodd y Grŵp Ymarferwyr Cymorth Cyfreithiol fod yr ôl-groniadau sylweddol yn llysoedd y Goron a llysoedd Ynadon Cymru a Lloegr yn golygu bod rhai achosion mewn perygl o beidio â chael eu herlyn. Dywedasant y gallai'r amser sydd wedi mynd heibio olygu na all tystion roi datganiadau cywir, dod yn anaddas neu benderfynu tynnu'n ôl o'r broses. Dywedasant hefyd fod yr oedi parhaus yn effeithio ar lesiant pobl sy'n aros i achosion fynd i'r llys.

Trafododd cynrychiolwyr bryderon hefyd y gallai ôl-groniadau llysoedd arwain at newidiadau sylfaenol i'r system gyfreithiol. Awgrymodd y Grŵp Ymarferwyr Cymorth Cyfreithiol y gallai'r newidiadau hyn gynnwys lleihau'r hawl i gael treial rheithgor, cyflwyno llysoedd canolradd neu gynyddu pwerau dedfrydu ynadon.

| “ | Mae'r llywodraeth yn sôn am newidiadau sylfaenol i strwythur sydd wedi'u datblygu am reswm da iawn dros amser i ddelio â phroblem nad oedd wedi'i hachosi gan y pandemig ond a waethygwyd ganddo oherwydd nad oes ganddyn nhw'r adnoddau i ddatrys y broblem. Felly, maen nhw'n ceisio dod o hyd i atebion sydd â chanlyniadau cyfansoddiadol sylweddol.

– Grŵp Ymarferwyr Cymorth Cyfreithiol |

Credwyd bod y cyhoedd wedi bod yn ddeallus i ddechrau ynghylch yr oedi i achosion llys a achoswyd gan y pandemig. Fodd bynnag, gostyngodd y goddefgarwch hwn wrth i'r pandemig fynd ymlaen a'r oedi i achosion llys barhau. Teimlai cynrychiolwyr fod hyn wedi arwain at ddirywiad sylweddol mewn ymddiriedaeth a hyder yn y system gyfiawnder. Disgrifiasant sut mae'r lefelau isel hyn o ymddiriedaeth y cyhoedd yn yr heddlu wedi parhau oherwydd y gred na fydd troseddau'n cael eu herlyn ac na fydd achosion yn mynd i'r llys.

| “ | Os nad ydych chi'n ymddiried yng ngallu'r system gyfiawnder i greu canlyniad teg a chosbi rhywun am rywbeth maen nhw wedi'i wneud, yna rydych chi'n colli ymddiriedaeth mewn sefydliadau yn gyffredinol. Rydym yn gweld rhai o'r goblygiadau hynny o ran hynny nawr, lefelau isel o hyder ar draws y bwrdd mewn sefydliadau cyhoeddus hanfodol, hanfodol.”

– Grŵp Ymarferwyr Cymorth Cyfreithiol |

Un canlyniad o ddirywiad ymddiriedaeth y cyhoedd yw gostyngiad yn nifer y dioddefwyr sy'n adrodd troseddau, tuedd a ddechreuodd yn ystod y pandemig ac sy'n parhau heddiw yn ôl cynrychiolwyr. Nododd Cymorth i Ddioddefwyr yr Alban fod canran y troseddau a adroddwyd gan y rhai sy'n nodi eu bod yn ddioddefwyr wedi gostwng o tua 40% cyn y pandemig i 29% nawr. Dywedodd y Grŵp Ymarferwyr Cymorth Cyfreithiol fod risg, os yw pobl yn llai tueddol o adrodd troseddau, y gallai hyn arwain at fwy o droseddu yn y tymor hir.

| “ | Rydym yn llawer llai tebygol o roi gwybod am drosedd nawr nag yr oeddem cyn Covid. Gwelodd y ffigurau ymddiriedaeth a hyder o ran y system gyfiawnder a system yr heddlu ostyngiad gwirioneddol yn ystod Covid ac maent wedi parhau.”

– Cymorth i Ddioddefwyr yr Alban |

Mynediad at gynrychiolaeth gyfreithiol

Siaradodd Cymdeithas Ymarferwyr Cyfraith Mewnfudo am sut y parhaodd yr arfer o ddarparu cyngor cyfreithiol o bell y tu hwnt i'r pandemig. Er bod hyn yn angenrheidiol yn ystod y pandemig oherwydd cyfyngiadau cadw pellter cymdeithasol a chyfyngiadau symud, awgrymasant fod yr arfer yn parhau ar ôl y pandemig oherwydd ei fod yn rhatach ac yn haws na darparu cyngor yn bersonol. Dywedasant mai effaith hyn yw bod gan y rhai nad oes ganddynt fynediad at ddyfeisiau digidol bellach fynediad llai i'r system gyfiawnder. Cwestiynasant degwch y newid hwn mewn arfer i'r rhai sy'n derbyn cyngor cyfreithiol.

| “ | Mae rhai mesurau wedi goroesi oherwydd amgylchiadau digynsail y pandemig, a allai fod wedi bod yn briodol yn ystod y pandemig i sicrhau bod rhywfaint o fynediad at gyfiawnder wedi'i ddarparu, ond nid ydym wedi ail-galibro yn y byd ôl-bandemig. Yn lle hynny, rydym wedi parhau â'r mesurau hyn, oherwydd eu bod yn effeithlon. Wrth effeithlon, dydw i ddim yn golygu teg. Roeddent yn effeithlon o ran arbed amser ac arian. Felly, efallai ein bod ni'n aberthu tegwch nawr er mwyn effeithlonrwydd.”

– Cymdeithas Ymarferwyr Cyfraith Mewnfudo |

Nododd y Grŵp Ymarferwyr Cymorth Cyfreithiol, er bod achosion cyfreithiol o bell yn galluogi ymarferwyr i ymdrin â nifer fwy o achosion ar draws ardal ddaearyddol fwy, oherwydd nad oeddent yn treulio amser yn mynychu achosion llys corfforol, fod y dull hwn yn y pen draw wedi lleihau ansawdd y gwasanaeth a dderbyniwyd gan gleientiaid. Awgrymasant fod darparu cyngor cyfreithiol o bell yn aml yn dod ar draul meithrin perthnasoedd â chleientiaid, yn enwedig ar gyfer cleientiaid mwy agored i niwed, gan effeithio ar ansawdd y gefnogaeth a dderbyniasant.

| “ | Yr hyn sydd wedi bod yn wir yn gyson o'r adborth rydyn ni wedi'i gael gan ymarferwyr, yw bod gwahaniaeth mesuradwy yn eich gallu i greu perthynas ymddiriedus gref gyda chleient [os ydych chi'n cwrdd â nhw yn bersonol] sy'n ofynnol os ydych chi'n mynd i gael cyfarwyddiadau da, rhoi cyngor da a helpu pobl trwy broses.”

– Grŵp Ymarferwyr Cymorth Cyfreithiol |

Gweithrediadau a chapasiti carchar

Tynnodd cynrychiolwyr sylw at effaith sylweddol a pharhaol y pandemig ar garchardai, yn enwedig capasiti carchardai. Nododd yr Ymddiriedolaeth Diwygio Carchardai fod y boblogaeth garchardai uchel barhaus wedi rhoi straen sylweddol ar y gwasanaethau cymorth sydd ar gael mewn carchardai. Mae hefyd wedi effeithio ar allu'r llysoedd i anfon carcharorion i garchardai sydd eisoes yn orlawn.

Cyfeiriodd cynrychiolwyr hefyd at yr effaith hirdymor ar lefelau staffio a gweithrediadau. Nododd Cynghrair Howard ddiffyg profiad ymhlith y staff presennol o sut i reoli carchardai mewn cyfnodau nad ydynt yn bandemig. Ymunodd llawer o aelodau staff carchardai â'r Gwasanaeth Carchardai yn ystod y pandemig ac maent ond wedi profi rheoli carchardai o dan fesurau cyfyngol Covid. Adroddodd Cynghrair Howard hefyd am effaith ar gadw staff gan fod carchardai wedi profi cyfradd uchel o drosiant staff.

| “ | Ni allaf feddwl am wasanaeth cyhoeddus sydd wedi’i effeithio’n fwy gan Covid-19. Cafodd ysgolion ac ysbytai effaith ofnadwy yn ystod y pandemig, ac mae ganddyn nhw broblemau adferiad o hyd, ond os ydym yn ystyried capasiti yn yr ystyr ehangach, o ran adnoddau staff, o ran yr hyn y mae carchardai’n ei gynnig, mae carchardai’n dal i gael trafferth dod allan o’r cyflwr pandemig hwnnw.”

– Cynghrair Howard |

-

-

- Mae Andrew Dodsworth yn Farnwr Dosbarth ac roedd yn Llywydd Cymdeithas Barnwyr Dosbarth Ei Mawrhydi 2021/22. Mynychodd y drafodaeth ford gron hon mewn rhinwedd bersonol.

- Mae Llys yr Eos yn llys dros dro yng Nghymru a Lloegr a sefydlwyd mewn ymateb i bandemig Covid-19.

- 'Ôl-groniad llysoedd troseddol', Audit Scotland (Mai 2023)

- Mae “remand” yn cyfeirio at yr arfer o gadw diffynyddion yn y ddalfa tra byddant yn aros am achos llys.

-

Gwersi i'w dysgu o'r pandemig

Awgrymodd cynrychiolwyr wersi allweddol y gellir eu dysgu o brofiad y sector cyfiawnder er mwyn paratoi'n well ar gyfer pandemigau yn y dyfodol ac ymateb iddynt.

- Cynllunio wrth gefn ar gyfer ymateb i bandemig a sut i ddod â chyfyngiadau i ben: Dylai fod cynlluniau clir ar gyfer sut mae'r heddlu, y llysoedd a'r carchardai yn ymateb i bandemig, ond hefyd ar gyfer llacio a dod â chyfyngiadau i ben. Mae hyn yn bwysig i leihau'r effaith hirdymor. Mae cynrychiolwyr eisiau i gynllunio wrth gefn dynnu ar wersi ac arferion gorau o brofiad Covid-19, gan gynnwys ystyriaeth briodol o effaith gwahanol ddulliau ar iechyd a lles dioddefwyr, carcharorion a staff. Fel rhan o unrhyw gynllunio wrth gefn, dylid asesu adeiladau fel carchardai a llysoedd i weld pa mor addas fyddent i'w defnyddio pe bai cyfyngiadau'n cael eu gosod yn ystod pandemig yn y dyfodol.

- Cydlynu a chyfathrebu â rhanddeiliaid allweddol yn y sector cyfiawnder: Dylai fod gwell ymgysylltiad rhwng y llywodraeth a sefydliadau sy'n gweithio mewn gwahanol rolau ar draws y sector cyfiawnder. Roeddent yn teimlo y byddai cyfathrebu gwell yn arwain at well gwneud penderfyniadau sy'n ystyried yr ystod o effeithiau posibl ar y sector.

- Defnyddio a darparu mynediad at dechnoleg: Mae'n bwysig myfyrio ar effaith gadarnhaol defnyddio technoleg yn ystod y pandemig a sicrhau bod mynediad cyfartal at dechnoleg.

- Gweithredu dulliau casglu data gwell i fesur effaith cyfyngiadau: Pwysleisiodd cynrychiolwyr bwysigrwydd gallu gwneud penderfyniadau sy'n seiliedig ar dystiolaeth. Maent am gael gwell casglu a dadansoddi data ar draws y sector er mwyn deall effaith barhaus penderfyniadau yn well.

- Diffiniad clir o weithwyr allweddol yn y system gyfiawnder: Dylid rhoi statws gweithiwr allweddol i bob gweithiwr Cyfiawnder yn ystod pandemig yn y dyfodol i'w cefnogi i gyflawni dyletswyddau hanfodol, fel mynychu achosion llys a pharatoi tystiolaeth. Byddai hefyd yn gwella eu mynediad at y PPE angenrheidiol, gan ddiogelu eu hiechyd a sicrhau bod y system gyfiawnder yn parhau i weithredu.

- Cydnabod pwysigrwydd cyswllt â ffrindiau a theulu fel ffactor amddiffynnol i'r rhai sydd yn y ddalfa: Dylai lleoedd cadw ddod o hyd i ffyrdd o roi mynediad i'r rhai sydd wedi'u cadw at eu teulu a'u ffrindiau i gefnogi eu hiechyd meddwl a'u lles.

- Trin y rhai sydd yn y ddalfa yn deg: Roedd cynrychiolwyr o'r farn ei bod hi'n bwysig trin carcharorion yn deg yn ystod pandemig yn y dyfodol, gan gynnwys ystyried effaith cyfyngiadau ar eu hiechyd meddwl a'u lles a sicrhau y gallant gael mynediad at y gofal iechyd, brechlynnau a gwasanaethau eraill sydd eu hangen arnynt.

Rhan B: yr effaith ar fewnfudo a lloches

Themâu allweddol

Effaith ar y system ymfudo a lloches

Effaith ar lefelau mudo

Esboniodd yr Arsyllfa Ymfudo fod nifer y bobl a oedd yn mudo i'r DU wedi gostwng yn sylweddol yn 2020, gan briodoli'r dirywiad hwn i deithio pandemig a chyfyngiadau eraill. Bu'r dirywiad hwn yn fyr wrth i niferoedd ymfudo godi eto yn 2021, gan ragori ar lefelau cyn y pandemig, a briodolasant yn rhannol i lacio cyfyngiadau'r pandemig.

Fe wnaethant sylwi bod gostyngiad o tua 20% yn nifer y ceisiadau am loches yn 2020, ond cynnydd sylweddol mewn croesfannau mewn cychod bach, gan godi o 1-2,000 cyn y pandemig i tua 8-9,000 yn 2020, a chynnydd sylweddol pellach yn 2021-22. Awgrymasant, yn hytrach na bod y pandemig yn atal y croesfannau hyn, fod y galw a lefel trefniadaeth y gweithgareddau hyn wedi cynyddu.

Roedd y cynnydd mewn croesfannau cychod bach yn golygu bod mwy o bobl yn hawlio lloches, gan gynyddu'r amser aros i geiswyr lloches gael eu ceisiadau wedi'u prosesu.

| “ | Gellir dadlau nad oedd y pandemig wedi gwneud llawer i atal y cymhelliant i fudo'n afreolaidd i'r DU. Roedd y croesfannau mewn cychod bach yn dod yn fwy proffesiynol, roedd y galw'n cynyddu, ac ni wnaeth [y pandemig] unrhyw effaith o ran croesi. O ran niferoedd cyffredinol y ceisiadau, cyrhaeddon ni niferoedd record ar ôl y pandemig.”

– Arsyllfa Ymfudo |

Effaith ar gasglu data mudo

Trafododd cynrychiolwyr sut y gwnaeth y pandemig amlygu diffygion sylweddol yng nghasglu data mewnfudo'r DU. Eglurwyd bod y pandemig wedi tarfu ar ddulliau casglu data traddodiadol a ddefnyddiwyd cyn y pandemig, fel yr Arolwg Teithwyr Rhyngwladol a chwalodd yn gyflym oherwydd cyfyngiadau teithio mewn meysydd awyr.

Defnyddiwyd yr Arolwg Llafurlu hefyd ond roedd yr ymateb i'r arolwg eisoes yn isel ac yn parhau i ostwng yn ystod y pandemig, gan godi pryderon ynghylch dibynadwyedd y data. Dywedodd yr Arsyllfa Ymfudo fod hyn yn ei gwneud hi'n anodd deall beth oedd yn digwydd i lefelau ymfudo yn y tymor byr.

Symudodd y Swyddfa Ystadegau Gwladol (ONS) i ddulliau casglu data amgen, fel defnyddio data gweinyddol o rifau Yswiriant Gwladol a gwiriadau ffin. Fodd bynnag, dywedwyd bod y newid hwn wedi creu anghysondebau yn y data, a oedd yn ei gwneud hi'n anodd deall tueddiadau mudo a gwneud cynlluniau effeithiol i fynd i'r afael ag effaith y pandemig ar fewnfudwyr.

Oedi yn y cynnydd mewn achosion

Cafodd y pandemig effaith negyddol ar ansawdd y gwasanaeth a ddarparwyd i fewnfudwyr a oedd yn llywio'r broses fewnfudo yn ôl cynrychiolwyr. Esboniodd Cymdeithas Ymarferwyr Cyfraith Mewnfudo fod rhai cyfreithwyr mewnfudo wedi cael eu rhoi ar ffyrlo yn ystod y pandemig, gan adael mewnfudwyr heb gefnogaeth gyfreithiol ar gyfer eu hachosion mewnfudo.

Roedd anawsterau wrth gael mynediad at ddogfennau achosion mewnfudo yn ystod y pandemig a oedd, yn ôl cynrychiolwyr, yn oedi datblygiad achosion ac yn peri gofid i fewnfudwyr. Mynegodd Cymdeithas Ymarferwyr Cyfraith Mewnfudo fod diffyg eglurder sylweddol ynghylch a oedd cyfreithwyr mewnfudo yn cael eu hystyried yn weithwyr allweddol a phryd, heblaw pan oeddent yn mynychu neu'n gweithio ar wrandawiadau llys a thribiwnlys. Tynasant sylw at enghraifft o ymarferydd yn gweithio ar gais i'r Swyddfa Gartref ac nid oedd yn glir a oedd yr ymarferydd yn weithiwr allweddol ac yn gallu mynd i gasglu dogfennau ffisegol o'r swyddfa i symud y mathau hyn o achosion ymlaen. Effeithiodd y gofyniad i weithio o gartref ar y gallu i gyflawni tasgau hanfodol fel llunio dogfennau neu gasglu tystiolaeth. Tynnodd cynrychiolydd y Cyngor ar y Cyd er Lles Mewnfudwyr sylw at oedi wrth brosesu ceisiadau mynediad at wybodaeth gan bwnc, gan effeithio ar y gallu i gasglu deunydd perthnasol.

Yn yr un modd, tynnodd yr Arsyllfa Ymfudo sylw at y ffaith bod y pandemig yn golygu bod cyfyngiadau ar gynnal cyfweliadau mewnfudo. Disgrifiasant sut y gellid hepgor rhai cyfweliadau ceisiadau am loches yn ystod y pandemig, ond bod hyn mewn gwirionedd yn ei gwneud hi'n anoddach symud ceisiadau ymlaen oherwydd bod llai o wybodaeth am achosion unigol.

Roedd oedi gwrandawiadau llys yn ystod y pandemig yn golygu bod rhaid i fewnfudwyr aros yn hirach i achosion gael eu datrys. Tynnodd yr Arsyllfa Ymfudo sylw at y ffaith bod oedi, yn enwedig wrth brosesu ceisiadau am loches, wedi parhau. Dywedasant erbyn 2023 fod dros hanner y penderfyniadau mewnfudo cychwynnol ar gyfer ceiswyr lloches ar gyfer unigolion a oedd wedi bod yn aros am fwy na 18 mis. Roeddent o'r farn bod hyn yn tynnu sylw at effaith barhaus aflonyddwch yn ystod y pandemig ar y system fewnfudo.

| “ | Gwnaeth yr holl newidiadau hynny a achoswyd gan y pandemig hi'n anoddach symud ceisiadau ymlaen. Wrth symud ymlaen i'r cyfnod ôl-bandemig: neidiodd ceisiadau, cyrhaeddiadau cychod bach, neidiodd popeth. Yna gwelwyd system a oedd yn sownd gyda cheisiadau'n symud ymlaen.”

– Arsyllfa Ymfudo |

Newidiadau i'r polisi

Achosodd y pandemig a'r newidiadau dilynol i'r system fewnfudo ansicrwydd ynghylch statws mewnfudo pobl, gyda chynrychiolwyr yn crybwyll enghreifftiau o gynlluniau a weithredwyd yn ystod y pandemig. Er enghraifft, cyflwynodd y Swyddfa Gartref gynllun consesiwn Covid-19 (Consesiwn Estyniad y Coronafeirws), a dywedodd cynrychiolydd Cymdeithas Ymarferwyr Cyfraith Mewnfudo fod hwn wedi ymestyn yr hawl i aros i'r rhai yr oedd eu fisâu yn dod i ben ym mis Gorffennaf 2020. Roedd hyn yn caniatáu iddynt aros yn y DU yn hirach yn ystod y pandemig. Fodd bynnag, dywedodd cynrychiolwyr fod diffyg eglurder ynghylch manylion y gwahanol gynlluniau mewnfudo coronafeirws wedi achosi dryswch sylweddol ac ansicrwydd cyfreithiol ynghylch statws mewnfudo unigolion. Esboniodd cynrychiolwyr fod absenoldeb canllawiau clir wedi gadael mudwyr mewn sefyllfa agored i niwed, gan arwain at golli statws mewnfudo rheolaidd a dirywiad dilynol yn eu gallu i weithio a chael mynediad at wasanaethau hanfodol.

Sefydlwyd cynllun disgresiynol ar wahân (y Gonsesiwn Sicrwydd Eithriadol) yn ystod y pandemig a oedd yn atal mudwyr a oedd yn wynebu canlyniadau andwyol rhag aros yn hwy na chyfnod penodol. Fodd bynnag, roedd cynrychiolwyr o'r farn bod y broses yn brin o dryloywder, gyda chanllawiau aneglur ynghylch sut y byddai penderfyniadau'n cael eu gwneud a pha unigolion a fyddai'n cael y statws hwn.

| “ | Dim ond blynyddoedd ar ôl ei gyflwyno ac ar ôl ceisio eglurhad cyson gan y Swyddfa Gartref y darganfuom nad oedd 'sicrwydd eithriadol' yn unrhyw fath o sicrwydd yn ôl y gyfraith. Roedd yn fath o 'amddiffyniad' ond nid oedd yn gyfystyr â phreswylio na phresenoldeb cyfreithlon yn y DU. Roedd y pŵer a'r mecanwaith cyfreithiol a oedd yn sail i'r sicrwydd hwn yn gwbl aneglur. Ar gyfer cynifer o'r polisïau dros dro yn ystod y pandemig, roedd yn rhaid i ni ofyn i'r Swyddfa Gartref gadw archifau o'u canllawiau eu hunain wrth iddynt esblygu'n barhaus, o ystyried nad oedd y polisïau hyn wedi'u cynnwys yn y Rheolau Mewnfudo.

– Cymdeithas Ymarferwyr Cyfraith Mewnfudo |

Soniodd cynrychiolwyr fod effaith y pandemig ar fewnfudo wedi'i chymhlethu ymhellach gan ymadawiad y DU o'r Undeb Ewropeaidd, a newidiodd hawliau mewnfudo dinasyddion yr UE sy'n byw yn y DU. Eglurwyd ganddynt fod rheolau mewnfudo wedi'u diwygio mewn ymateb i'r pandemig heb ystyried yr effaith ar ddinasyddion yr UE. Er enghraifft, collodd dinasyddion yr UE a aeth yn ôl i'w gwledydd cartref yn ystod y cyfnod clo eu hawl i aros yn y DU, gan ei gwneud hi'n anodd iddynt ddod yn ôl.

| “ | Nid oedd digon o hyblygrwydd yn y gofynion mewnfudo yn ystod pandemig Covid-19. Roedd gorgyffwrdd y pandemig byd-eang cyntaf â Brexit yn golygu nad oedd pobl yn gallu bodloni gofynion am resymau y tu hwnt i'w rheolaeth.

– Cymdeithas Ymarferwyr Cyfraith Mewnfudo |

Effaith ar fewnfudwyr a cheiswyr lloches

Iechyd meddwl a lles

Cynrychiolydd Prosiect 17, sy'n gweithio i roi terfyn ar dlodi ymhlith teuluoedd mudol heb unrhyw hawl i arian cyhoeddus5, disgrifiodd sut y golygodd y pandemig nad oedd gan fewnfudwyr a cheiswyr lloches fynediad at eu rhwydweithiau cymorth arferol, fel defnyddio llyfrgelloedd i gael cynhesrwydd, defnyddio cyfleusterau rhyngrwyd mewn lleoliadau bwyd, neu rannu bwyd gyda ffrindiau, a bod hyn i gyd yn effeithio ar eu hiechyd meddwl. Nodasant hefyd nad oedd gan rai mewnfudwyr fynediad at fannau awyr agored cyfagos ar gyfer awyr iach ac ymarfer corff yn ystod y pandemig, gan effeithio'n negyddol ar eu hiechyd meddwl a chorfforol.

| “ | Cafodd cleientiaid eu holi am fod ar fainc y parc oherwydd nad oedd ganddyn nhw ardd. Roedden nhw wedi’u dal yn eu hystafelloedd gwely bryd hynny.”

– Prosiect 17 |

Roedd llai o gefnogaeth ar gael i fewnfudwyr a cheiswyr lloches yn ystod y pandemig yn ôl y cynrychiolwyr. Roedd hyn yn cynnwys cefnogaeth iechyd meddwl a diffyg cefnogaeth gyffredinol ar gael yn eu hiaith eu hunain. Dywedodd cynrychiolwyr fod hyn wedi cael effaith negyddol ar lesiant. Yn benodol, canfu Prosiect 17 fod y diffyg cefnogaeth iechyd meddwl ar gael yn ystod y pandemig wedi gwaethygu ofnau mewnfudwyr na fyddai'r llywodraeth yn darparu cymorth iddynt hwy na'u teuluoedd. Nododd Mechnïaeth i Garcharorion Mewnfudo yn yr un modd fod y pandemig a'r driniaeth o fewnfudwyr yn ystod y cyfnod hwn wedi meithrin ymdeimlad nad oeddent yn bwysig, gan leihau eu hymdeimlad o berthyn a niweidio eu hiechyd meddwl.

| “ | Ni allaf gofio unrhyw gefnogaeth iechyd meddwl ychwanegol [yn ystod y pandemig] i bobl gyrraedd eu cymunedau a'u teulu a'u ffrindiau.”

– Cymdeithas Ymarferwyr Cyfraith Mewnfudo |

Mudwyr sydd wedi'u cadw

Dywedodd cynrychiolwyr fod gan y pandemig effaith negyddol sylweddol ar iechyd meddwl a lles mewnfudwyr a gedwir yn y ddalfa. Esboniodd y cynrychiolydd ar gyfer Mechnïaeth i Garcharorion Mewnfudo fod carcharorion yn destun cyfnodau estynedig o gaethiwed ar eu pennau eu hunain mewn ymdrech i leihau lledaeniad Covid-19 o fewn cyfleusterau cadw. Dywedasant fod rhai mewnfudwyr yn cael eu caethiwo am dros 23 awr bob dydd. Tynnasant sylw at y ffaith bod y diffyg cyfathrebu clir ynghylch y rhesymau dros hyn a hyd disgwyliedig eu caethiwed yn arwain at fwy o ofn a phryder ymhlith carcharorion.

| “ | Oherwydd bod pobl wedi’u cyfyngu yn eu celloedd: roedden nhw’n byw mewn ofn y gallen nhw gael Covid, y gallen nhw farw, na fydden nhw’n gwybod beth oedd yn digwydd yn y byd y tu allan.”

– Mechnïaeth i Garcharorion Mewnfudo |

Dywedodd Bail for Importants Detainees nad oedd mudwyr sy'n cael eu cadw yn y ddalfa yn cael ymweliadau gan deulu a ffrindiau yn bersonol na mynediad at dechnoleg ddigonol fel fideo-gynadledda neu ffonau i gyfathrebu â'u rhwydweithiau cymorth. Roedd y diffyg cyswllt â rhwydweithiau cymorth yn gwaethygu eu hynysu cymdeithasol ac yn gwneud iddynt deimlo nad oedd eu hiechyd meddwl yn flaenoriaeth. Nododd y Cyngor Cydweithredol dros Les Mewnfudwyr fod mudwyr sy'n cael eu cadw yn y ddalfa hefyd yn teimlo eu bod yn cael eu gwrthod mynediad at wasanaethau cymorth a brechlynnau Covid-19. Dywedasant fod hyn yn gwaethygu'r effaith ar eu hiechyd meddwl ac yn cynyddu ofn ynghylch dal Covid-19.

| “ | Dyma’r ymdeimlad o reolaeth. Y rhan fwyaf ohonom yn yr amgylchiadau hynny, gallwn greu’r rhith o reolaeth drwy wisgo mwgwd ac ati. I’r rhai mewn canolfannau cadw, mae fel bod yn y blitz: cuddio o dan y gwely a gobeithio y byddwch chi’n osgoi’r bom. Ni allwch chi wneud dim – mae rhywun arall yn rheoli eich bywyd ac mae effaith hynny’n aruthrol.”

– Prosiect 17 |

Esboniodd Mechnïaeth i Garcharorion Mewnfudo ymhellach fod canolfannau cadw mewnfudo yn cael anawsterau wrth sicrhau llety amgen addas ar gyfer carcharorion risg uchel. Roedd hyn oherwydd oedi yn y broses gymeradwyo gan wasanaethau prawf, gan arwain at fewnfudwyr risg uchel yn cael eu cadw am gyfnodau hir er gwaethaf cael mechnïaeth. Fe wnaethant dynnu sylw at y ffaith, erbyn mis Mai 2020, fod hyd cyfartalog y cyfnod cadw mewn achosion yr oedd wedi darparu cynrychiolaeth neu wedi cynghori arnynt wedi codi i dros 200 diwrnod, mewn cyferbyniad â'r cyfartaledd cyn-pandemig o 60 diwrnod.

Effaith ariannol

Dywedodd cynrychiolydd Prosiect 17 fod cynnydd o 66% mewn ceisiadau am gymorth gyda thai a chymorth ariannol. Roedd yna hefyd fwy o ddibyniaeth ar fanciau bwyd yn ystod y pandemig. Roeddent yn teimlo nad oedd rhai mudwyr yn cydymffurfio â rheolau'r pandemig wrth iddynt barhau i weithio i gynnal eu hunain a'u teuluoedd.

| “ | Fel cymdeithas, weithiau rydyn ni’n teimlo nad yw mudwyr yn bwysig. Wrth wynebu pandemig, mae’r ymateb yn dibynnu’n effeithiol ar allu pobl i gydymffurfio. Dw i’n meddwl bod pobl eisiau, ond os nad oes gennych chi fwyd yn y tŷ, allwch chi ddim. Os nad oes neb yn darparu dihangfa, rydych chi’n tanseilio ymateb y cyhoedd i ganllawiau’r llywodraeth.”

– Prosiect 17 |

Trafododd cynrychiolwyr effaith cynnydd mewn ffioedd fisa yn ystod y pandemig, a gyd-ddigwyddodd â chynnydd yng nghost byw. Nododd Prosiect 17 fod hyn yn aml yn lleihau unrhyw arian yr oedd mudwyr wedi'i arbed ac yn cynyddu'r straen ariannol yn ystod y broses fewnfudo, yn enwedig i'r rhai nad oeddent yn gymwys i gael eu hepgor rhag ffioedd yn ystod y pandemig.

Nid oedd gan rai mudwyr ddigon o arian i ymdopi â chostau claddu teulu a ffrindiau a fu farw yn ystod y pandemig, a effeithiodd yn sylweddol ar eu profiadau galar yn ôl cynrychiolydd Prosiect 17.

| “ | Creulondeb peidio â gallu cael cymorth gyda chostau claddu a phrofedigaeth. Pan nad ydyn nhw'n cael dau ben llinyn ynghyd ac yn wynebu amddifadedd, ni allent ymdopi â chostau claddu rhywun a fu farw o'r pandemig.

– Prosiect 17 |

Mynediad i lety

Arweiniodd y pandemig at newidiadau yn y ddarpariaeth llety i fewnfudwyr oherwydd prinder tai cymunedol. Esboniodd Cymdeithas Ymarferwyr Cyfraith Mewnfudo fod y llywodraeth wedi dechrau defnyddio llety wrth gefn, fel gwestai, barics y fyddin a thai cymysg eu meddiannaeth. Dywedodd cynrychiolydd Prosiect 17 fod y cyfleusterau hyn yn aml yn orlawn, gan gynyddu'r risg o drosglwyddo Covid-19 ac nad oeddent bob amser yn darparu bwyd maethlon a phriodol yn ddiwylliannol. Fe wnaethant hefyd ddyfynnu un archwiliad a ganfu 200 o unigolion yn cysgu ar y llawr mewn sachau cysgu, nad oedd yn cydymffurfio â safonau llety.

| “ | Roedd llawer o'r llety y rhoddodd y cyngor bobl ynddo yn dai cymysg eu meddiannaeth. Dywedwyd wrth bobl am amddiffyn eu hunain ond yna cawsant eu rhoi mewn lleoedd gydag eraill a allai fod â phroblemau camddefnyddio sylweddau. Roeddent yn ofni gadael eu hystafelloedd i fynd i'r gegin. Roedd yn rhaid iddynt adael plant gartref heb ofal plant i weithio wedyn.”

– Prosiect 17 |

Arweiniodd y pandemig hefyd at effeithiau hirdymor ar y llety a ddarperir i geiswyr lloches, gyda mwy o ddibyniaeth ar westai. Nododd yr Arsyllfa Ymfudo fod y llwyth parhaus o geisiadau lloches yn golygu bod gwestai lloches yn parhau i gael eu defnyddio ar gost i'r unigolyn a'r llywodraeth.

| “ | Mae'n rhaid i chi gynnig cefnogaeth a darparu llety i'r bobl. Ond i'r unigolyn, maen nhw'n sownd mewn limbo heb yr hawl i weithio a byw oddi ar gefnogaeth Adran 95.6 Mae hynny'n dod â llawer o ganlyniadau i'r bobl hynny."

– Arsyllfa Ymfudo |

Mynediad at ofal iechyd

Nododd Cymdeithas Ymarferwyr Cyfraith Mewnfudo nad oedd canllawiau'r llywodraeth ynghylch Covid-19 a'i effaith ar y system fewnfudo wedi'u darparu mewn fformatau y gallai mudwyr eu deall, gyda sgiliau llythrennedd yn rhwystr sylweddol. Creodd hyn fylchau gwybodaeth sylweddol ynghylch mesurau Covid-19, mynediad at ofal iechyd, newidiadau polisi a brechlynnau. O ganlyniad, nid oedd llawer o fudwyr yn ymwybodol o'r adnoddau gofal iechyd a oedd ar gael iddynt yn ystod y pandemig felly ni wnaethant eu defnyddio.

Fe wnaeth y GIG eithrio unrhyw un sy'n byw yn y DU heb ganiatâd rhag taliadau am ofal iechyd Covid-19, gan gynnwys profi am Covid-19, triniaeth ar gyfer Covid-19 a brechiadau. Cyfarwyddwyd staff gofal iechyd hefyd i beidio â chynnal y gwiriadau mewnfudo arferol wrth ddarparu gwasanaethau gofal iechyd Covid-19. Fodd bynnag, teimlai cynrychiolwyr fod mudwyr a cheiswyr lloches yn parhau i fod yn ofnus ynghylch cael mynediad at wasanaethau oherwydd eu diffyg ymddiriedaeth yn yr awdurdodau. Cafodd hyn ei yrru gan ofnau y gallai eu statws mewnfudo gael ei adrodd i'r Swyddfa Gartref. Awgrymodd Cymdeithas Ymarferwyr Cyfraith Mewnfudo hefyd nad oedd llawer o fudwyr wedi'u cofrestru gyda meddygon teulu ac nad oedd ganddynt rif GIG ac felly na allent gael mynediad at ofal iechyd Covid-19.

| “ | Roedd mudwyr a gafodd eu digalonni rhag cael mynediad at ofal iechyd am amser hir yn sinigaidd ynghylch y posibilrwydd o gael mynediad ato’n sydyn yn ystod pandemig Covid-19.

– Y Cyngor Cydweithredol dros Lles Mewnfudwyr |

Disgrifiodd y cynrychiolydd dros Fechnïaeth i Garcharorion Mewnfudo ddiffyg eglurder ynghylch pwy oedd yn gymwys i gael brechlyn Covid-19, a greodd ansicrwydd i garcharorion mudol ynghylch a allent gael brechlyn ac amddiffyn eu hunain rhag Covid-19.

Pobl heb fynediad at arian cyhoeddus

Tynnodd cynrychiolwyr sylw at effaith niweidiol y pandemig ar fewnfudwyr sy'n byw heb fynediad at arian cyhoeddus (NRPF), a waethygwyd gan beidio â chael mynediad at rwydweithiau cymorth arferol, fel ffrindiau a theulu, yn ogystal â gwasanaethau fel llyfrgelloedd.

Esboniodd Prosiect 17 fod mudwyr ag NRPF yn aml yn cael eu cyflogi mewn swyddi cyflog isafswm neu'r economi anffurfiol (swyddi nad ydynt yn cael eu trethu, eu monitro na'u rheoleiddio gan y llywodraeth) a'u bod yn aml yn byw mewn amodau gorlawn. Er gwaethaf canllawiau'r llywodraeth, roedd llawer yn teimlo nad oedd ganddynt ddewis ond parhau i weithio drwy gydol y pandemig, gan beryglu haint a throsglwyddo Covid-19 o fewn eu cartrefi. Nododd Prosiect 17 hefyd gynnydd mewn cam-drin domestig a digartrefedd ymhlith mudwyr ag NRPF yn ystod y pandemig.

| “ | Gan nad oedd ganddyn nhw fynediad at arian cyhoeddus, roedden nhw'n wynebu effaith wirioneddol newyn a pheidio â gallu bwydo eu plant.”

– Prosiect 17 |

- Dim hawl i gronfeydd cyhoeddus (NRPF): mae'n amod a roddir ar rai statws mewnfudo yn y DU, sy'n golygu na all y rhai sydd ag NRPF hawlio'r rhan fwyaf o fudd-daliadau, credydau treth, na chymorth tai gan y wladwriaeth. Mae hyn yn rhan o lawer o fisâu dros dro ac ar gyfer y rhai heb unrhyw ganiatâd cyfreithiol i fod yn y DU.

- Mae Adran 95 o Ddeddf Mewnfudo a Lloches 1999 yn caniatáu i geiswyr lloches sy'n amddifad, neu sy'n debygol o ddod yn amddifad, gael cymorth gan Swyddfa Gartref y DU. Gall y cymorth hwn gynnwys llety a chymorth ariannol i dalu am anghenion byw hanfodol. Mae'r cymorth yn parhau tra bod y cais am loches yn cael ei brosesu, gan gynnwys unrhyw apeliadau.

Gwersi i'w dysgu o'r pandemig

Awgrymodd cynrychiolwyr wersi allweddol y gellir eu dysgu o brofiad y sector mewnfudo a lloches er mwyn paratoi'n well ar gyfer pandemigau yn y dyfodol ac ymateb iddynt.

- Cipio data mudo dibynadwy: Disgrifiodd cynrychiolwyr yr angen i sicrhau y gall casglu data barhau i weithredu yn ystod pandemig er mwyn deall pwy sy'n dod i mewn ac allan o'r DU. Fe wnaethant bwysleisio y dylai'r system hon hefyd gasglu data ar fewnfudwyr a deithiodd yn anghyfreithlon. Roeddent o'r farn y byddai'r data hwn o gymorth i baratoi polisi mudo effeithiol mewn pandemig.

- Cefnogi cynnydd achosion mewnfudo: Dylid cydnabod cynrychiolwyr cyfreithiol yn gyson fel gweithwyr allweddol er mwyn eu galluogi i barhau i weithio a datblygu achosion.

- Gwella mynediad at ofal iechyd: Mewn pandemigau yn y dyfodol, dylid cymryd camau effeithiol i fynd i'r afael â'r pryder y byddai data gofal iechyd a gesglir yn cael ei rannu ag awdurdodau mewnfudo. Ystyriwyd bod hyn yn bwysig ar gyfer meithrin ymddiriedaeth, a fyddai wedyn yn helpu i leddfu ofnau a chamwybodaeth ymhlith mudwyr a cheiswyr lloches. Dylid gwneud gofal iechyd yn hygyrch trwy ddarparu cefnogaeth a gwybodaeth mewn gwahanol ieithoedd.

Atodiad

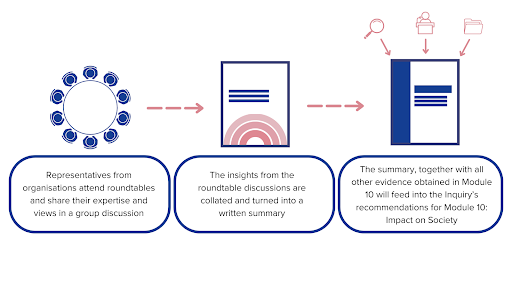

Strwythur y bwrdd crwn

Ym mis Mai 2025, cynhaliodd Ymchwiliad Covid y DU gyfarfod bwrdd crwn i drafod effaith y pandemig ar y system cyfiawnder troseddol a'r system fewnfudo a lloches. Roedd y drafodaeth bwrdd crwn hon yn cynnwys tair trafodaeth grŵp yn canolbwyntio ar y sector cyfiawnder, y sector carchardai a'r sector mewnfudo a lloches.