Ang ilan sa mga kuwento at tema na kasama sa talaang ito ay kinabibilangan ng mga paglalarawan ng kamatayan, mga karanasang malapit nang mamatay, makabuluhang pisikal at sikolohikal na pinsala at mga pagtukoy sa mga karanasan ng pang-aabuso. Ang ilan sa mga paglalarawang ito ay nauugnay din sa mga karanasan ng mga bata. Ang mga kwentong ito ay maaaring nakababahalang basahin. Kung gayon, hinihikayat ang mga mambabasa na humingi ng tulong mula sa mga kasamahan, kaibigan, pamilya, grupo ng suporta o mga propesyonal sa pangangalagang pangkalusugan kung kinakailangan. Ang isang listahan ng mga suportang serbisyo ay ibinibigay din sa UK Covid-19 Inquiry website.

Paunang salita

Ito ang pangatlong tala ng Every Story Matters, na ginawa para sa imbestigasyon ng Module 7: Test, Trace at Isolate para sa Covid-19 Inquiry. Ang lahat ng mga tala ng Every Story Matters ay isinumite bilang ebidensya sa Chair of the Inquiry, Baroness Hallett, at magiging bahagi ng opisyal na pampublikong rekord ng Inquiry.

Ang Bawat Story Matters ay idinisenyo upang tipunin at maunawaan ang karanasan ng tao sa pandemya sa United Kingdom. Maraming libu-libong tao ang nagbahagi ng kanilang mga kuwento sa amin, at gusto naming pasalamatan ang mga taong naglaan ng oras upang gawin ito. Ang tungkulin ng Bawat Story Matters bilang isang 'pagsasanay sa pakikinig' ay nangangahulugan na ang halaga nito ay nasa pagdinig ng isang hanay ng mga karanasan, pagtukoy sa mga tema kung saan posible at, mahalaga, pagtiyak na ang mga karanasan ng mga tao ay bahagi ng pampublikong rekord ng Inquiry at maaaring isaalang-alang kapag bumubuo ng mga rekomendasyon. Dapat nating maunawaan ang epekto ng pandemya upang makagawa ng mga rekomendasyon na makakabawas sa mga pinsala mula sa isang pandemya sa hinaharap.

Titingnan ng Module 7 ang diskarte sa pagsubok, pagsubaybay at paghihiwalay sa panahon ng pandemya na pinagtibay ng Pamahalaan ng UK at mga devolved na administrasyon sa Northern Ireland, Scotland at Wales. Ang modyul ay tuklasin ang mga patakaran, estratehiya at desisyong ginawa ng mga pangunahing katawan at salik na maaaring nakaimpluwensya sa pampublikong pagsunod sa mga opisyal na alituntunin. Ang Bawat Story Matters ay nagdaragdag ng kakaibang pananaw ng tao, tinutuklas ang papel ng pag-uugali at karanasan ng mga tao sa loob ng konteksto ng sistemang ito ng pagsubok, pagsubaybay at paghihiwalay. Ang malinaw ay maraming tao ang nadala ng pagnanais na protektahan ang mga tao sa kanilang paligid, kabilang ang mga mas mahina.

Nagpapasalamat kami sa mga indibidwal, grupo at organisasyon na nagbigay sa amin ng feedback, ideya at tumulong sa amin na makarinig mula sa malawak na hanay ng mga tao. Kabilang sa mga ito ang: Long Covid Kids, Long Covid Scotland, Long Covid SOS, Long Covid Support, Clinically Vulnerable Families, SignHealth at ang Royal National Institute of Blind People. Ang bawat isa sa mga grupong ito ay nagbigay-daan sa amin na makipag-usap sa kanilang mga miyembro at matiyak na ang kanilang mga karanasan ay bahagi ng talaang ito.

Isang pribilehiyo na magtrabaho sa kakaibang aspetong ito ng Pagtatanong sa Covid-19.

Ang koponan ng Every Story Matters

Pangkalahatang-ideya

Ang maikling buod na ito ay nagbibigay ng mataas na antas na pangkalahatang-ideya ng mga tema mula sa maraming kuwentong narinig namin kaugnay ng pagsubok, pagsubaybay sa pakikipag-ugnayan at pag-iisa sa sarili sa panahon ng pandemya.

Paano sinuri ang mga kwento

Ang bawat kuwentong ibinahagi sa Inquiry ay sinusuri at mag-aambag sa isa o higit pang may temang mga dokumentong tulad nito. Ibinahagi ng mga tao ang kanilang mga karanasan sa Inquiry sa iba't ibang paraan. Ang mga kwentong naglalarawan ng mga karanasan ng pagsubok, pagsubaybay sa pakikipag-ugnay at pag-iisa sa sarili sa panahon ng pandemya ay pinagsama-sama at sinuri upang i-highlight ang mga pangunahing tema. Sa buod:

- Sinuri namin ang 44,775 na kwentong isinumite online sa Inquiry sa oras na isinulat ang rekord na ito, gamit ang natural language processing (NLP) at sinusuri at coding ng mga mananaliksik ang ibinahagi ng mga tao.

- Pinagsama-sama ng mga mananaliksik ang mga tema mula sa 340 na kwento ng mga tao na ibinahagi sa mga panayam sa pananaliksik at mga talakayan ng grupo.

- Ang mga mananaliksik ay gumuhit din ng mga tema mula sa Every Story Matters na mga kaganapan sa pakikinig kasama ang publiko at mga grupo ng komunidad sa mga bayan at lungsod sa buong England, Scotland, Wales at Northern Ireland. Gumawa kami ng punto ng pagsasalita sa mga miyembro ng mga pangunahing grupo kung saan gustong marinig ng Inquiry legal team.

Ang higit pang mga detalye tungkol sa kung kanino namin narinig at kung paano pinagsama-sama at sinuri ang mga kuwento ng mga tao sa talaang ito ay kasama sa apendiks. Ang dokumentong ito ay sumasalamin sa iba't ibang mga karanasan nang hindi sinusubukang ipagkasundo ang mga ito; kinikilala namin na ang karanasan ng bawat isa ay natatangi.

Sa buong talaan, tinukoy namin ang mga taong nagbahagi ng kanilang mga kuwento sa Every Story Matters bilang 'mga contributor'. Ito ay dahil may mahalagang papel sila sa pagdaragdag sa ebidensya ng Inquiry at sa opisyal na rekord ng pandemya. Kung naaangkop, inilarawan din namin ang higit pa tungkol sa kanila (halimbawa, mga taong may iba't ibang kapansanan o kondisyon ng kalusugan) o ang dahilan kung bakit ibinahagi nila ang kanilang kuwento (halimbawa, bilang mga tagapag-alaga o magulang). Ito ay upang makatulong na ipaliwanag ang konteksto ng kanilang kuwento.

Ang ilang mga kuwento ay ginalugad nang mas malalim sa pamamagitan ng mga quote at case study. Pinili ang mga ito upang i-highlight ang mga partikular na karanasan at ang epekto ng mga ito sa mga tao. Ang mga quote at case study ay nakakatulong sa pag-ground ng record sa kung ano ang ibinahagi ng mga tao sa Inquiry sa sarili nilang mga salita. Ang mga kontribusyon ay hindi nagpapakilala. Gumamit kami ng mga pseudonym para sa mga case study na nakuha mula sa mga panayam sa pananaliksik. Ang mga karanasang ibinahagi ng ibang mga pamamaraan ay walang mga pseudonym.

Pag-unawa at kamalayan ng Test, Trace at Isolate

Marami sa mga nagbahagi ng kanilang mga kuwento ang nagsabi sa amin na ang patnubay ay malinaw na may kaugnayan sa kung kailan magsusuri para sa Covid-19 at kung kailan maghihiwalay sa sarili. Habang umiral ang ilang pagkalito tungkol sa pag-alam sa pagkakaiba sa pagitan ng mga sintomas ng Covid-19 at iba pang katulad na sakit, tulad ng sipon at trangkaso, ang kamalayan at kumpiyansa sa kakayahang matukoy ang mga sintomas ay lumago sa panahon ng pandemya.

| “ | Sa pag-unlad nito sa paglipas ng panahon, naiintindihan namin kung kailan namin kailangan na subukan. Ito ay medyo malinaw.

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

Ilang nag-ambag ang kumuha ng dalawang beses-lingguhang mabilis na pagsusuri nang maging available ito sa lahat noong Abril 2021 at ang ilan ay nahirapan sa katwiran para sa pagsusuri nang walang mga sintomas. Ang pagsubok na walang mga sintomas ay nauugnay sa kinakailangang gawin ito o dahil sa isang pangangailangan o pagnanais na makihalubilo sa iba.

Ang kamalayan at pag-unawa sa patnubay tungkol sa pagsubaybay sa contact ay hindi gaanong kalat. Narinig namin na mas mahirap maunawaan ang layunin ng pagsubaybay sa pakikipag-ugnay at kung paano sundin nang tama ang gabay.

Ang kamalayan sa pinansiyal at praktikal na suporta upang matulungan ang mga tao kapag ang pagbubukod sa sarili ay medyo mababa din.

| “ | Oo, hindi ko alam kung paano ito hahanapin, o kung ano pa man. Sa tingin ko, hindi naging maayos, malawak. Ang impormasyon para sa [pinansyal na tulong] ay hindi masyadong kumalat, dahil wala akong natatandaan tungkol sa £500.”

– Clinically vulnerable na tao |

Ang mga pagbabago sa opisyal na patnubay ng pamahalaan ay nagdulot ng pagkalito sa mga tao tungkol sa kung kailan magsusuri at maghihiwalay sa sarili. Nangangahulugan ang kawalan ng katiyakan tungkol sa mga alituntuning ipinatupad sa anumang oras, na, sa bandang huli ng pandemya, nagpasya ang ilang tao na gawin kung ano ang sa tingin nila ay angkop kahit na ito ay naaayon o hindi sa mga panuntunan.

| “ | Nakaramdam lang ako ng pagkalito sa buong bagay kung kailan kami dapat mag-test, sa anong yugto mo dapat subukan [...] patuloy nilang binabago ang mga patakaran tungkol dito."

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

Ano ang nakatulong o naghikayat sa mga tao na lumahok sa pagsusuri, pagsubaybay sa pakikipag-ugnayan at pag-iisa sa sarili?

Maraming dahilan kung bakit handa ang mga tao na subukan at ihiwalay ang sarili, at maraming paraan ng pagtulong at paghikayat sa kanila na gawin ito.

- Pagprotekta sa mga taong pinapahalagahan nila: Para sa marami, ang pakiramdam ng moral na tungkulin na protektahan ang kanilang mga mahal sa buhay, ang kanilang mga komunidad at ang mga taong mahina ay nag-udyok sa kanila na makilahok sa pagsubok, pagsubaybay sa pakikipag-ugnay at pag-iisa sa sarili.

| “ | Ito ay [pag-iisa sa sarili] isa sa ilang bagay na may katuturan, dahil ang talagang ginagawa mo ay pinoprotektahan mo ang mga taong pinapahalagahan mo."

– Tagapag-alaga |

- Mga kinakailangan: Ang ilang mga tao ay kinakailangang magpasuri (anuman ang mga sintomas) bago pumasok sa trabaho at makipag-ugnayan sa ibang tao. Inilarawan ito ng ilan bilang bahagi ng kanilang 'tungkulin ng pangangalaga' na protektahan ang iba.

- Access sa suporta: Para sa ilan, ang suporta na kanilang natanggap - mula sa pamilya at mga kaibigan, mga lokal na organisasyon at mga grupo ng komunidad - ay nagbigay-daan sa kanila na makisali sa pagsubok, pagsubaybay sa pakikipag-ugnay at upang ihiwalay ang sarili.

| “ | Ang aming mga lokal na tindahan ay kamangha-mangha sa pag-aayos ng mga paghahatid ng pagkain para sa amin. Kami ay mapalad na nakatira sa isang rural na lugar at maaaring gumugol ng oras sa hardin. Ngunit sa palagay ko ito ay isang mas positibong karanasan kaysa sa inaasahan namin. Minsan sinasabi ng anak ko na nami-miss niya ang closeness na iyon.”

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

- Kalayaan: Sa paglipas ng panahon, ang pagnanais na pumasok sa mga paaralan, kolehiyo at unibersidad, maglakbay at makihalubilo at makihalubilo sa iba ay naging dahilan ng pagsubok.

| “ | Sasabihin ko na naging mas mahalaga ang pagsubok, bilang isang pagsasanay. […] at lalo na […] kung ang mga tao ay bumibisita sa amin o […] Gusto kong […] makakita ng ibang tao, ang pagsubok para sa aking sarili at ang paghiling sa lahat na gawin iyon ay naging talagang mahalaga. Malamang na mas mahalaga kaysa makita sila, sa totoo lang."

– Miyembro ng pamilya o tagasuporta ng isang tao na kinakailangang ihiwalay ang sarili |

- Pag-alis ng takot: Ang mga tao ay natatakot na mahawaan ang virus at maging malubha o maipasa ito at sa gayon ay nasubok, nakikibahagi sa pagsubaybay sa pakikipag-ugnay at nag-iisa sa sarili.

- Access at kaginhawaan: Kung saan ang mga testing center ay madaling puntahan, at ang pagkakaroon ng mga appointment ay mabuti, nakita ng mga tao na madaling magpasuri. Nang ang Lateral Flow Tests (LFTs) ay ginawang available sa lahat ng tao noong Abril 2021, marami ang malugod na tinanggap ang kadalian at kaginhawahan ng mga libreng kit para masuri sa bahay.

| “ | Ang mga test center at vaccination center ay talagang madaling mag-book ng mga appointment at lahat ay nasa loob ng maikling distansya ng paglalakbay.

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

Ano ang mga hadlang sa mga taong lumahok sa pagsubok, pagsubaybay sa pakikipag-ugnay at pag-iisa sa sarili?

Mayroong maraming mga tema na huminto o nagpahirap sa mga tao na mag-test, makipag-ugnayan sa pagsubaybay sa pakikipag-ugnay at upang ihiwalay ang sarili kapag kailangan nila.

- Tiwala: Ang pag-aalinlangan at kawalan ng tiwala ay lumago habang ang mga tao ay nakaranas ng mga problema sa pagsubok at pagsubaybay sa pakikipag-ugnay dahil inakala nila na sila ay hindi tumpak o hindi epektibo.

| “ | Hindi pa ako nakapagpositibo sa isang lateral flow test, ngunit alam ko na ang mga ito ay hindi na akma para sa layunin, at sa halip ay alam kong mayroon akong Covid dahil sa mga nakapaligid sa akin na may parehong mga sintomas na sumusubok na positibo sa oras na iyon.

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

- Pagdama ng panganib: Kung gaano kalaki ang personal na panganib na kumportable ng mga tao ay nakaimpluwensya sa kanilang pakikibahagi sa pagsubok, pagsubaybay sa pakikipag-ugnay at pag-uugali sa pag-iisa sa sarili, at nagbago ito sa buong pandemya.

| “ | Dumating sa punto [na] lahat ay nagsawa na, kasama ko […] na parang ikaw lang, 'O, tuloy ang buhay.' Parang, hindi ka mabubuhay ng ganito sa natitirang bahagi ng iyong buhay, […] unti-unti mo nang nabawasan ang pansin. Hindi sa hindi pa rin ako mag-iingat hanggang sa isang lawak, ngunit hindi katulad ng magiging sukat ko sa unang dalawang taon.”

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

- Access: Kung saan nakaranas ang mga tao ng mga hadlang sa pag-access (halimbawa, pag-book ng PCR test kapag mahirap i-navigate o i-access ang mga LFT sa system sa panahon ng kakulangan ng supply), mas mahirap ang pagsubok para sa Covid-19, at nagdulot ng pag-aalala at paghihirap.

| “ | Ang mga sentro ng pagsubok sa Covid ay maayos at mabuti kung madaling ma-access ng mga tao ang mga ito, na magagawa ko lamang sa pamamagitan ng paglalakbay sa pamamagitan ng hindi bababa sa dalawang uri ng pampublikong sasakyan habang nakahiwalay."

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

- Accessibility at pagsasama: Ang mga hadlang ay lumitaw kung saan ang mga testing center ay hindi naa-access ng mga tao, kung saan ang mga tagubilin sa LFT kit ay mahirap maunawaan at gamitin, at kung saan ang mga tao ay hindi kasama sa mga digital na anyo ng pagsubaybay sa contact.

| “ | Napakaraming komunidad ang hindi marunong bumasa at sumulat, at sila ay umaasa sa mga miyembro ng pamilya upang gawin ito ng marami para sa kanila.”

– Taong mula sa pinagmulang etniko ng Roma |

- Kahirapan sa paggamit: Narinig din namin na ang mga tao ay nakaranas ng mga hadlang sa paggamit ng mga LFT nang tama, pagbibigay kahulugan sa mga resulta at paglipat sa pagitan ng iba't ibang variation ng mga test kit.

- Mga negatibong epekto: Sinabi sa amin ng mga tao ang tungkol sa mga negatibo, o potensyal na negatibo, na mga epekto kapag nakikibahagi sa pagsusuri, pagsubaybay sa pakikipag-ugnayan at pag-iisa sa sarili. Kabilang dito ang pagkawala ng personal na kalayaan, mga epekto sa kapakanan ng mga tao – kabilang ang kakulangan sa ginhawa at pagkabalisa mula sa pagsubok – at ang mga hamon ng pag-iisa sa sarili.

| “ | Ilang Covid test lang ang ginawa ko – kung may nakita akong mas hindi kasiya-siya kaysa sa pagbabakuna.”

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

- Mga kaayusan sa pamumuhay: Para sa ilan, hindi palaging praktikal na sundin ang patnubay - lalo na tungkol sa pag-iisa sa sarili - halimbawa, kung nakatira sila sa mas maliliit o masikip na bahay.

- Kakulangan ng panlipunang suporta at insentibo: Kung saan walang access ang mga tao sa suportang panlipunan, nahirapan silang makisali sa pagsubok, pagsubaybay sa contact at pag-iisa sa sarili. Ang katotohanan na ang pag-uulat ng mga resulta ng pagsusulit ay hindi kinokontrol ay nangangahulugan na ang ilan ay nagtanong sa halaga ng pagsubok sa unang lugar.

| “ | Ang pag-upload ng mga resulta ng pagsusulit ay isang komedya rin dahil maaari kong i-upload ang mga resulta ng pagsusulit ng aking kapitbahay [natatawa]. Walang garantiya na iyon ang aking mga resulta. Ganap na kalokohan.”

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

Ang mga karanasan ng mga magulang, mga sumuporta sa iba at mga nakaligtas sa pang-aabuso sa tahanan

Narinig namin mula sa maraming iba't ibang tao na nag-uusap tungkol sa kanilang mga karanasan sa pagsubok, pagsubaybay sa contact at pag-iisa sa sarili. Sa kabanatang ito, nakatuon tayo sa mga kuwento ng mga taong nahirapan sa mga aspetong ito ng pandemya. Kabilang dito ang mga magulang na kinailangang subukan ang maliliit na bata at mga nakaligtas sa pang-aabuso sa tahanan na kinailangang ihiwalay ang sarili sa mga kasosyo na nang-abuso sa kanila at/o hindi sumunod sa mga patakaran.

Mga mungkahi para sa mga pagpapabuti para sa hinaharap

Kapag iniisip kung paano mapapabuti ang pagsubok, pagsubaybay sa pakikipag-ugnayan at pag-iisa sa sarili sa isang pandemya sa hinaharap, sinabi ng mga kontribyutor na maaaring makatulong ang sumusunod:

- Higit na pagkakapare-pareho at kalinawan sa mga patakaran at pagmemensahe ng gobyerno sa mga bansang nakipag-devolve

- Higit pang pampublikong edukasyon sa pangangailangan para sa pagsubok, pagsubaybay sa pakikipag-ugnay at pag-iisa sa sarili

- Pinahusay na access sa suporta sa kalusugan ng isip at pinansyal at praktikal na suporta para sa mga tao sa mga panahon ng pag-iisa sa sarili

- Mas mahusay na paggamit ng mga pinuno ng komunidad sa pagpapalaganap ng impormasyon sa mga komunidad

- Mga alternatibong opsyon para sa digitally ibinukod na mga tao at sa mga nakatira sa liblib o rural na lugar

- Magagamit na impormasyon sa iba't ibang wika at format

Buong record

1. Panimula

Inilalahad ng dokumentong ito ang mga kwentong ibinahagi sa Every Story Matters na may kaugnayan sa Covid-19 testing, contact tracing at self-isolation.

Background at layunin

Ang Every Story Matters ay isang pagkakataon para sa mga tao sa buong UK na ibahagi ang kanilang karanasan sa pandemya sa UK Covid-19 Inquiry. Ang bawat kwentong ibinahagi ay susuriin at ang mga insight na nakuha ay gagawing mga may temang dokumento para sa mga nauugnay na module ng Inquiry. Ang mga talaang ito ay isinumite sa Pagtatanong bilang ebidensya. Sa paggawa nito, ang mga natuklasan at rekomendasyon ng Inquiry ay ipapaalam ng mga karanasan ng mga naapektuhan ng pandemya.

Pinagsasama-sama ng dokumentong ito ang sinabi sa amin ng mga nag-aambag tungkol sa kanilang mga karanasan sa pagsusuri sa Covid-19, pagsubaybay sa pakikipag-ugnayan at pag-iisa sa sarili sa panahon ng pandemya. Para sa rekord na ito, ang self-isolation ay tumutukoy sa isang taong naghihiwalay pagkatapos makatanggap ng positibong resulta ng pagsusuri sa Covid-19 o isang abiso tungkol sa isang malapit na contact na mayroong Covid-19 sa pamamagitan ng contact tracing system. Habang ang mga indibidwal na pinayuhan na mag-shield ay kinapanayam, ang mga panayam ay nag-explore ng kanilang pakikipag-ugnayan sa Test, Trace at Isolate system, hindi ang kanilang mga karanasan na may kaugnayan sa shielding.1 Ang tala na ito ay hindi kasama ang mga karanasan ng pagiging nakahiwalay o mga pakiramdam ng paghihiwalay bilang resulta ng isang pambansang lockdown.

Isinasaalang-alang ng UK Covid-19 Inquiry ang iba't ibang aspeto ng pandemya at kung paano ito nakaapekto sa mga tao. Nangangahulugan ito na ang ilang mga paksa ay tatalakayin sa iba pang mga tala ng module. Samakatuwid, hindi lahat ng karanasang ibinahagi sa Every Story Matters ay kasama sa dokumentong ito. Halimbawa, ang mga karanasan ng UK healthcare system at mga karanasan ng mga bakuna at therapeutics ay ginalugad sa iba pang mga module at kasama sa iba pang mga tala ng Every Story Matters. Matuto pa tungkol sa Bawat Kwento ay Mahalaga at basahin ang nakaraan mga tala.

Paano ibinahagi ng mga tao ang kanilang mga karanasan

Mayroong ilang iba't ibang paraan kung paano namin nakolekta ang mga kuwento ng mga tao para sa Modyul 7, ang mga ito ay nakalista sa ibaba.

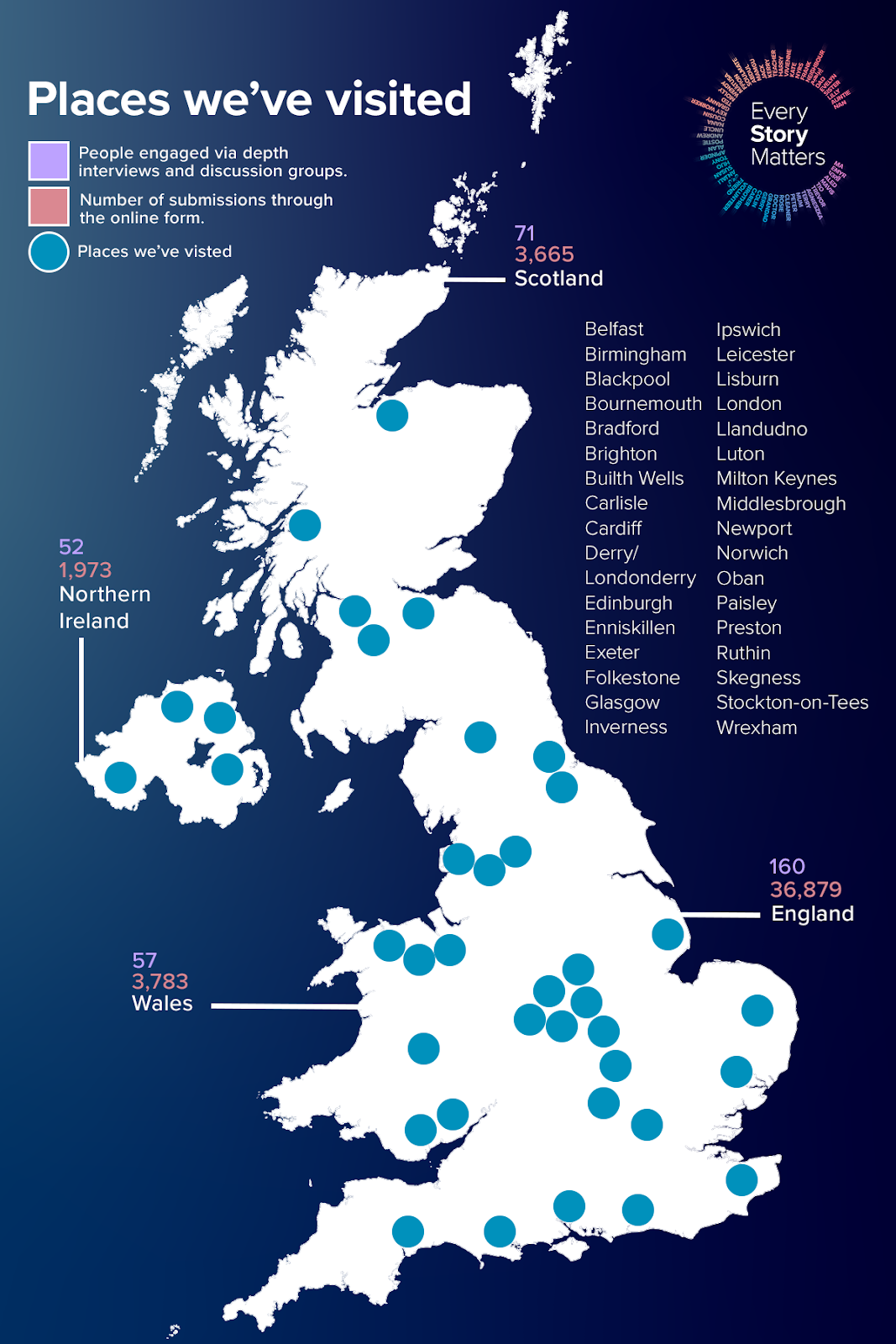

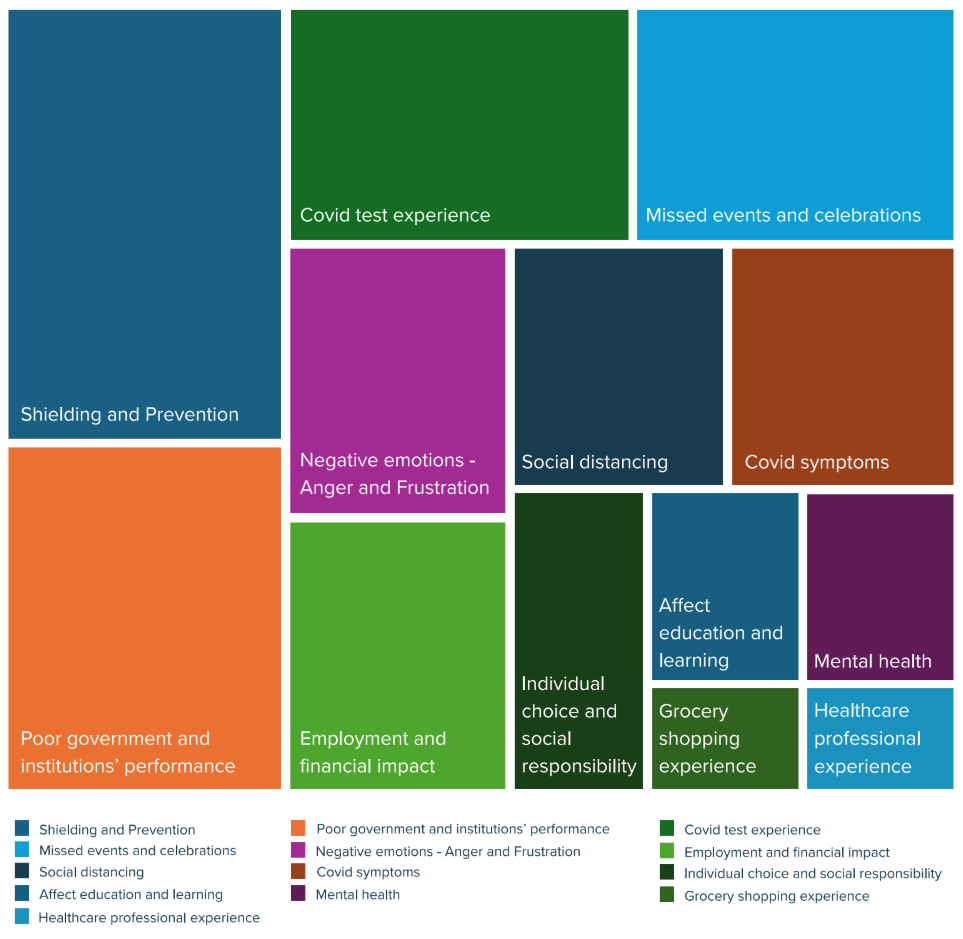

- Ang mga miyembro ng publiko ay inanyayahan upang kumpletuhin ang isang online na form sa pamamagitan ng website ng Inquiry (mga papel na form ay inaalok din sa mga kontribyutor at kasama sa pagsusuri). Hiniling nito sa kanila na sagutin ang tatlong malawak at bukas na mga tanong tungkol sa kanilang karanasan sa pandemya. Ang form ay nagtanong ng iba pang mga katanungan upang mangolekta ng background na impormasyon tungkol sa kanila (tulad ng kanilang edad, kasarian at etnisidad). Nagbigay-daan ito sa amin na marinig mula sa napakaraming tao ang tungkol sa kanilang mga karanasan sa pandemya. Ang mga tugon sa online na form ay isinumite nang hindi nagpapakilala. Para sa Modyul 7, sinuri namin ang 44,775 kuwento. Kasama rito ang 36,879 na kuwento mula sa England, 3,665 mula sa Scotland, 3,783 mula sa Wales at 1,973 mula sa Northern Ireland (nakapili ang mga nag-aambag ng higit sa isang bansa sa UK sa online na form, kaya mas mataas ang kabuuan kaysa sa bilang ng mga natanggap na tugon). Sinuri ang mga tugon sa pamamagitan ng 'natural language processing' (NLP), na tumutulong sa pagsasaayos ng data sa makabuluhang paraan. Sa pamamagitan ng algorithmic analysis, ang impormasyong nakalap ay isinaayos sa 'mga paksa' batay sa mga termino o parirala. Ang mga paksang ito ay sinuri ng mga mananaliksik upang matuklasan pa ang mga kuwento. Higit pang impormasyon sa NLP ay matatagpuan sa apendiks.

- Sa oras ng pagsulat ng talaang ito, ang koponan ng Every Story Matters ay napunta sa 33 bayan at lungsod sa buong England, Wales, Scotland at Northern Ireland upang bigyan ang mga tao ng pagkakataong ibahagi ang kanilang karanasan sa pandemya nang personal sa kanilang mga lokal na komunidad. Idinaos din ang mga virtual na sesyon sa pakikinig, kung ang pamamaraang iyon ay ginusto ng mga kalahok. Ang koponan ay nakipagtulungan sa maraming kawanggawa at mga grupo ng komunidad sa katutubo upang makipag-usap sa mga naapektuhan ng pandemya sa mga partikular na paraan. Para sa partikular na record na Every Story Matters, mga karanasan mula sa Bingi2 isinama ang mga tao at mga taong bahagyang nakikita. Ang mga maikling buod na ulat para sa bawat kaganapan ay isinulat, ibinahagi sa mga kalahok ng kaganapan at ginamit upang ipaalam ang dokumentong ito. Isang consortium ng panlipunang pananaliksik at mga eksperto sa komunidad ang inatasan ng Every Story Matters na magsagawa malalim na mga panayam at mga grupo ng talakayan upang maunawaan ang mga karanasan ng iba't ibang tao, batay sa gustong maunawaan ng legal team para sa Module 7. Kasama rito ang mga may partikular na kundisyon sa kalusugan na maaaring nakaapekto sa kanilang kakayahang sumubok o ihiwalay ang sarili, kabilang ang mga kondisyon at kapansanan sa pisikal at mental na kalusugan. Kasama rin dito ang mga miyembro ng pamilya o mga indibidwal na sumusuporta sa mga kinakailangang mag-self-isolate, lalo na sa mga sumusuporta sa mga matatandang tao, naulila na mga indibidwal, o mga naulilang kaibigan, pamilya at mga kasamahan, mga may dati nang kondisyong pangkalusugan, o yaong mga clinically vulnerable o shielding. Kasama rin ang mga may mga responsibilidad sa pag-aalaga at mga miyembro ng mga grupo ng komunidad upang tulungan ang mga tao na ihiwalay ang sarili. Ang mga panayam at grupo ng talakayan na ito ay nakatuon sa Mga Pangunahing Linya ng Pagtatanong (KLOEs) para sa Module 7, impormasyon kung saan makikita dito. Sa kabuuan, 340 katao sa buong England, Scotland, Wales at Northern Ireland ang nag-ambag sa ganitong paraan sa pagitan ng Hulyo at Oktubre 2024. Ang lahat ng malalalim na panayam at grupo ng talakayan ay naitala, na-transcribe, na-code at sinuri upang matukoy ang mga pangunahing tema na nauugnay sa Module 7 KLOEs.

- Ang bilang ng mga tao na nagbahagi ng kanilang mga kuwento sa bawat bansa sa UK sa pamamagitan ng online na form, mga kaganapan sa pakikinig at mga panayam sa pananaliksik at mga grupo ng talakayan ay ipinapakita sa ibaba:

Figure 1: Pakikipag-ugnayan sa Bawat Story Matters sa buong UK

Para sa karagdagang impormasyon kung paano kami nakinig sa mga tao at ang mga pamamaraang ginamit sa pagsusuri ng mga kuwento, pakitingnan ang apendiks.

Mga tala tungkol sa presentasyon at interpretasyon ng mga kuwento

Ang mga kuwentong nakolekta sa pamamagitan ng Every Story Matters ay hindi kumakatawan sa lahat ng karanasan. Naapektuhan ng pandemya ang lahat sa UK sa iba't ibang paraan, at habang lumalabas ang mga pangkalahatang tema at pananaw mula sa mga kuwento, kinikilala namin ang kahalagahan ng natatanging karanasan ng bawat isa sa nangyari. Nilalayon ng record na ito na ipakita ang iba't ibang karanasang ibinahagi sa amin, nang hindi sinusubukang i-reconcile ang magkakaibang mga account.

Ginagamit namin ang terminong 'marami' upang ilarawan kung saan laganap ang mga karanasan at 'ilan' kung saan hindi gaanong karaniwan ang mga ito.

Ang ilang mga kuwento ay binibigyang buhay sa pamamagitan ng mga quote. Pinili ang mga ito para i-highlight ang iba't ibang uri ng karanasang narinig namin at ang epekto nito sa mga tao. Ang mga quote ay tumutulong sa pag-ground ng record sa kung ano ang ibinahagi ng mga tao sa kanilang sariling mga salita. Ang mga kontribusyon ay hindi nagpapakilala.

Sa pamamagitan ng rekord, makikita mong tinutukoy namin ang mga taong nagbahagi ng kanilang mga kuwento sa Every Story Matters bilang 'mga nag-aambag' at kung minsan ay naglalarawan kami ng higit pa tungkol sa kanila (halimbawa, ang kanilang etnisidad o katayuan sa kalusugan) upang makatulong na magbigay ng higit na konteksto sa quote na ginamit namin. Para sa mga taong nag-ambag sa record na ito sa pamamagitan ng isang webform, ang lahat ng kanilang mga quote ay may label na "Every Story Matters contributor". Ang ilan na nagsabi sa amin ng kanilang mga kuwento sa pamamagitan ng mga focus group at mga panayam ay may label din sa ganitong paraan. Ito ay dahil ang karagdagang detalye tungkol sa kanilang background ay hindi gaanong nauugnay upang suportahan ang naunang teksto, ngunit ang kanilang mga karanasan ay mahalaga pa ring isama.

Ang mga kuwento ay kinolekta at sinuri sa buong 2023 at 2024, ibig sabihin, ang mga karanasan ay naaalala ilang sandali pagkatapos mangyari ang mga ito, na nakakaimpluwensya sa mga detalye at aspeto ng mga karanasang naaalala.

Istruktura ng talaan

Ang dokumentong ito ay nakabalangkas upang bigyang-daan ang mga mambabasa na maunawaan kung paano naranasan ng mga tao ang pagsusuri sa Covid-19, pagsubaybay sa pakikipag-ugnayan at pag-iisa sa sarili.

Nagsisimula ang rekord sa pamamagitan ng paggalugad sa pag-unawa ng mga tao sa pagsubok, pagsubaybay at paghihiwalay (Kabanata 2) bago magpatuloy upang talakayin ang mga salik na nag-udyok (Kabanata 3) at nawalan ng loob (Kabanata 4) ang mga tao na lumahok sa pagsubok, pagsubaybay sa pakikipag-ugnay at pag-iisa sa sarili. Ang talaan pagkatapos ay nakatuon sa mga karanasang ibinahagi sa amin ng mga nag-aambag sa mga partikular na pangyayari (Kabanata 5). Sa wakas, tinutuklasan nito ang mga potensyal na pagpapabuti sa paligid ng pagsubok, pagsubaybay at pag-iisa sa sarili para sa mga pandemya sa hinaharap (Kabanata 6).

Terminolohiyang ginamit sa talaan

Pagsubok ay tumutukoy sa mga taong gumagamit ng kagamitan (inilalarawan sa ibaba) upang matukoy kung mayroon silang Covid-19 o wala.

Bakas ay tumutukoy sa prosesong ginamit upang tukuyin kung ang mga tao ay nakipag-ugnayan sa isang virus, sa kasong ito ng Covid-19, upang ang paghahatid ng virus ay maaaring pamahalaan at maitago hangga't maaari.

Ihiwalay ay tumutukoy sa panahon kasunod ng isang positibong pagsusuri sa Covid-19, na kadalasang tinutukoy bilang 'pag-iisa sa sarili'. Nagbago ang panahong ito sa paglipas ng pandemya at iba ito sa mga pakiramdam ng paghihiwalay na nangyari bilang resulta ng mga pambansang pag-lock.

Pinag-uusapan natin ang tungkol sa Lateral Flow Tests (LFTs) at Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) na mga pagsubok na dalawang pagsubok na ginamit upang matukoy ang pagkakaroon ng Covid-19.

Mga Pagsubok sa Lateral Flow (LFT)

Ang mga LFT ay isang home test na ginagamit upang makita ang isang aktibong impeksiyon. Gumagana ang pagsubok sa pamamagitan ng pagtuklas ng mga protina na naroroon sa isang pamunas na kinuha mula sa ilong at/o lalamunan. Nagtatampok ang pagsubok ng isang maliit na device na may absorbent pad sa isang dulo at isang reading window sa kabilang dulo. Sa loob ng device ay isang strip ng test paper na nagbabago ng kulay kung mayroong mga protina ng Covid-19.

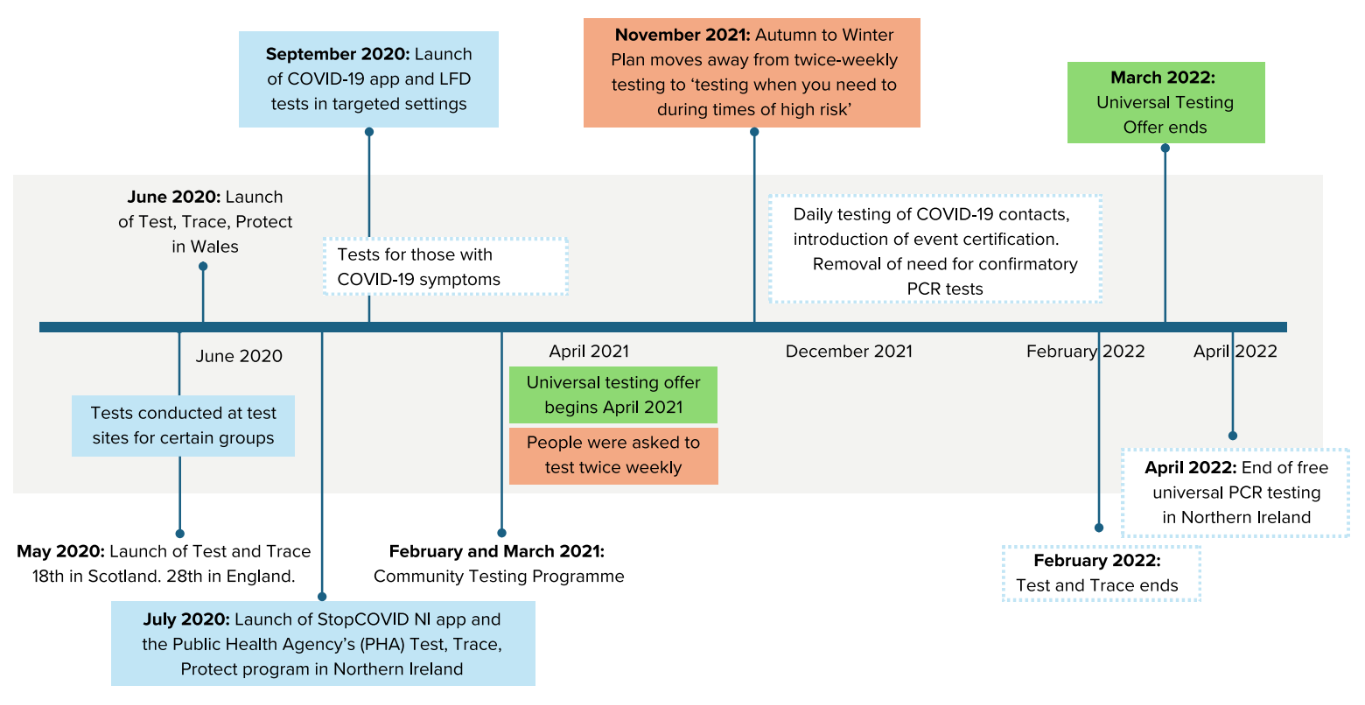

Ang Lateral Flow Tests (LFTs) ay ginawang available sa lahat sa England, Scotland at Wales noong Abril 2021 na nagbigay-daan sa libreng access sa mabilis na pagsubok. Sumunod ang Northern Ireland noong Setyembre 2021.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

Gumagana ang PCR test sa pamamagitan ng pagkuha ng sample gamit ang pamunas, kadalasan mula sa ilong at/o lalamunan. Pagkatapos ay ipapadala ang pamunas sa isang lab kung saan sinusuri ang sample para sa genetic material ng SARS-CoV-2 virus (Covid 19).

- Ang mga taong tinukoy bilang clinically very vulnerable at samakatuwid ay nasa napakataas na panganib ng malubhang sakit mula sa Covid-19 ay pinayuhan na 'magsanggalang' (ibig sabihin, protektahan ang kanilang sarili sa pamamagitan ng hindi pag-alis sa kanilang mga tahanan at bawasan ang lahat ng harapang pakikipag-ugnayan).

- Kinikilala ng Inquiry ang mas malawak na inklusibong termino ng "d/Deaf" bagama't ang mga taong kinakausap bilang bahagi ng record na kinilala bilang "Bingi".

2. Pag-unawa at kamalayan ng Test, Trace at Isolate |

|

Sinasaliksik ng kabanatang ito ang kamalayan at pag-unawa ng mga nag-aambag sa pagsubok, pagsubaybay sa contact at pag-iisa sa sarili at ang mga panuntunang kailangan nilang sundin. Inilalarawan nito kung paano nalilito ang ilang tao sa mga komunikasyon, pati na rin ang mga karanasan ng mga nag-aambag sa kalidad ng impormasyong makukuha.

Pag-unawa at kamalayan sa patnubay

Inilarawan ng maraming kontribyutor kung paano nila naunawaan na kailangan nilang subukan kung mayroon silang mga sintomas ng Covid-19, tulad ng pag-ubo, pangkalahatang sintomas ng trangkaso - halimbawa, sipon at namamagang lalamunan - at pagkawala ng lasa at amoy. Ang kaalaman sa patnubay na ito ay dumating sa pamamagitan ng impormasyon mula sa mga awtoridad na ayon sa batas, ang NHS, mga employer at iba pang may kadalubhasaan sa medisina.

| “ | Palagi nilang ipinapaliwanag na [dapat kang magpasuri] anumang oras na naramdaman mong nagkakaroon ka ng mga sintomas, o kung nakipag-ugnayan ka sa isang taong nagpositibo sa Covid, o – kailangan mong magpasuri kung lilipad ka rin.”

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

Inilarawan ng ilang kontribyutor kung paano lumaki ang kanilang kamalayan at kumpiyansa sa pag-alam kung kailan magsusuri sa paglipas ng panahon bilang resulta ng pagkakaroon ng mga sintomas at pagkaranas ng virus o pagdinig tungkol sa mga karanasan ng iba sa Covid-19.

| “ | Ang aking kumpiyansa [sa pagtukoy sa mga sintomas ng Covid-19] ay lumago sa paglipas ng panahon, pagkatapos kong marinig ang mga unang karanasan ng mga tao na alam kong […mayroon] nito. Dahil sa unang yugto, ito talaga ang makikita mo sa balita […], ang mga tao sa mga ventilator, at talagang, talagang seryoso […Akala ko] sinumang nakakuha ng Covid ay nasa bangkang iyon. Ngunit malinaw naman habang nagbabago ang mga strain, ngunit ang mga sintomas ay nanatiling magkatulad, lahat kami ay nagsimulang matuto.

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

Ilang tao ang narinig namin mula sa alok ng dalawang beses na lingguhang mabilis na pagsubok (gamit ang mga LFT) noong inilunsad ito sa lahat mula Abril 2021 pataas. Sinabi sa amin ng mga tao na kapag nagpasuri sila nang walang mga sintomas, karamihan ay dahil sa mga kinakailangan sa lugar ng trabaho (saklaw sa ibaba) o gustong magpasuri bago makihalubilo sa iba (tingnan ang seksyong 'Mga Kalayaan' sa ibaba). Ang ilang mga nag-aambag ay nahirapan sa katwiran para sa pagsusuri nang walang mga sintomas, kadalasang nalilito kung paano kumalat ang virus sa pagitan ng mga tao nang hindi nagdudulot ng mga sintomas.

| “ | Nagpositibo ang anak ko, ngunit wala siyang anumang sintomas, kaya napakahirap malaman kung ano ang mga sintomas."

– Taong nagtatrabaho sa mga bata |

Naunawaan ng mga nagbahagi ng kanilang mga kwento na ang pagkakaroon ng mga sintomas ng Covid-19 ay nangangahulugang kailangan nilang ihiwalay ang sarili. Gayundin, sa karamihan (at lalo na sa simula ng pandemya), naunawaan ng mga tao na ang pagtanggap ng positibong pagsusuri para sa Covid-19 ay nangangahulugan ng pag-iisa sa sarili. Sinabi sa amin ng ilang kontribyutor kung paano sila naghiwalay sa sarili noong inakala nilang hindi tumpak ang mga resulta mula sa isang LFT dahil sa kanilang mga sintomas, o kapag naghihintay ng PCR test o dumating ang resulta.

| “ | Ihihiwalay namin [sa sarili] kung mayroon din kaming mga sintomas, hindi lamang sa pagsubok, dahil takot na takot kaming ibigay ito sa ibang tao dahil alam namin kung ano iyon."

– Nakaligtas sa pang-aabuso sa tahanan |

Inilarawan ng ilang nag-aambag kung paano nila sinubukan ang pandemya sa bandang huli (karaniwang gumagamit ng LFT) para kumpirmahin kung nakontrata ba sila ng Covid-19 bago magpasya kung mag-iisa o hindi.

| “ | Sa tingin ko, tulad ng tagapag-ayos ng buhok, kung saan nag-ping sila sa akin at sinabing, 'Nalantad ka, kailangan mong ihiwalay ang sarili mo sa loob ng pitong araw.' Nag-test ako sa bahay, at wala ako nito, at hindi ako nag-self-isolate. Sa palagay ko nagsusuri ako araw-araw, o bawat ibang araw."

– Taong may kapansanan |

Marami rin ang nakaunawa sa patnubay na ihiwalay ang sarili at subukan kung nakipag-ugnayan sila sa isang taong nagpositibo sa Covid-19. hindi alintana kung sila ay nakakaranas ng mga sintomas o hindi.

| “ | Nagkaroon ako ng tatlong PCR test […] na napakalapit [… Una] ang aking anak na babae […] ay nakaramdam ng hindi magandang pakiramdam, [… nang] ang isang tao sa kanyang paaralan ay nagkaroon ng Covid, kaya pumunta kaming lahat at nagpasuri. At pagkatapos ay nag-positive talaga siya sa bahay […] kaya nag-book kami ng PCR para sa aming lahat [kinabukasan]. At pagkatapos ay naging positibo ako [pagkalipas ng ilang araw].”

– Taong nabubuhay na may Long Covid |

| “ | Sigurado akong bumalik kami sa drama group [kapag may nasubok] na positibo para sa Covid [...] lahat ng iba ay gagawa lang ng pagsubok upang matiyak na [hindi nila ito nakuha]."

– Clinically vulnerable na tao |

Sinabi sa amin ng mga tao na mas naiintindihan nila ang mga proseso sa paligid ng pagsubok at pag-iisa sa sarili kumpara sa mga konektado sa pagsubaybay sa contact. Inilarawan ng ilang kontribyutor kung paano nila nakitang hindi malinaw ang impormasyon sa pagsubaybay sa contact, na mahirap maunawaan ang layunin nito at sundin nang tama ang gabay.

| “ | Ang pag-iisa sa sarili, naiintindihan ng lahat. Pagsubok, naiintindihan ng lahat. Ang pagsubaybay sa bit, kung marahil ay hindi ipinaliwanag kung bakit ito mahalaga o kung paano ito gumagana, o kung paano gumagana ang teknolohiya, o kung ano ang napakalinaw na isa, dalawa, tatlong hakbang na kailangan mong gawin. I think that bit for me, nagkaroon ng confusion.”

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

Hindi alam ng maraming tao ang aming narinig mula sa pinansyal at praktikal na suporta upang tumulong sa panahon ng pag-iisa sa sarili. Bagama't sa pangkalahatan ay hindi alam na ang ganitong uri ng suporta ay magagamit, ang ilan ay sumasalamin na tatanggapin nila ito sa oras na iyon. Ipinaliwanag nila na mapapawi sana nito ang ilan sa pinansiyal na pasanin, lalo na para sa mga naapektuhan ang kita ng hindi makapagtrabaho. Para sa iba na nagtatrabaho at nagtatrabaho, binanggit ng ilan na hindi nila naisip na mag-aplay para sa suportang pinansyal.

| “ | Hindi ko man lang naisip na mag-apply, hindi ko akalain, kasi nagtatrabaho pa ako, kaya hindi ko naisip na nag-apply man lang ako.”

– Taong may pangmatagalang pisikal na kondisyon sa kalusugan |

| “ | Kinailangan kong gumawa ng maraming pananaliksik at makipag-usap din sa maraming tao upang makakuha ng sarili nilang mga karanasan sa kung ano ang nalaman nilang magagamit nila, mula rin sa pananaliksik. Sa palagay ko ay hindi ito madaling magagamit [impormasyon tungkol sa suporta para sa pag-iisa sa sarili] at sa palagay ko marami ring maling impormasyon."

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

Nakarinig kami ng ilang halimbawa ng mga nag-aambag na nakarinig tungkol sa suportang pinansyal, partikular para sa pag-iisa sa sarili, sa pamamagitan ng salita ng bibig o sa kanilang trabaho. Nakita ng ilan na nakakatulong ito habang ang iba ay nagsabi sa amin na mas gusto nilang kumita ng sarili nilang pera sa halip na tuparin ang buong panahon ng pag-iisa sa sarili.

| “ | I did access them [grants to self-isolate], gusto ko lang ng pera. Na-access ko ang mga ito ngunit pagkatapos ay pinutol ko ang panahon upang kumita ng mas maraming pera. Dahil lahat ay gustong kumita ng mas maraming pera."

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

| “ | Oo, maganda ang £500, sa totoo lang. Ang £500 na iyon para sa mga naapektuhan ng Covid ay talagang mahusay. Ngunit hindi lahat ay nakatanggap nito."

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

Ang mga mapagkukunan ng impormasyon tungkol sa kung saan maa-access ang mga pagsusulit ay kasama ang internet, telebisyon, social media, mga polyeto at salita ng bibig. Ang mga nag-aambag na naalala na alamin ang tungkol sa mga pagsubok sa mga ganitong paraan ay nadama na ang impormasyon ay madaling makuha, malinaw at madaling sundin.

| “ | Naaalala ko na palagi nilang sasabihin sa iyo sa balita kung paano i-access ito [pagsubok]. Kung pumunta ka sa website ng NHS, magkakaroon ito ng malinaw na mga tagubilin. O kahit na tumawag ako sa aking GP, ipapaalam nila sa akin […] kung paano i-access ang mga ito [… Ang impormasyon] ay hindi masyadong kumplikado […] tulad ng ilang mga payo.”

– Tagapag-alaga |

Narinig din namin mula sa mga kontribyutor na naglalarawan ng mga kahirapan sa pag-access o pagsubaybay sa impormasyon tungkol sa pagsubok. Kasama rito ang mga taong hindi gumagamit ng internet at mga taong hindi Ingles ang unang wika. Ang limitadong pag-access sa impormasyon ay nangangahulugang hindi alam ng ilang nag-ambag na maaari nilang ma-access ang mga pagsubok nang libre, halimbawa, hanggang sa ilang paraan sa pandemya. Ang ilan ay hindi rin sigurado kung saan makakahanap ng mga pagsubok, o kung ano ang gagawin kapag may kakulangan.

Pagkalito

Sinabi sa amin ng ilang kontribyutor kung paano sila nalilito kung kailan at bakit sila susubok. Kadalasan ito ay dahil mahirap makilala ang Covid-19 at iba pang mga sakit dahil sa pagkakaiba-iba at kalubhaan ng mga sintomas na nauugnay sa Covid-19 at iba pang mga virus tulad ng sipon at trangkaso. Ang pinaghihinalaang kahirapan ay naging dahilan upang ang ilang mga kontribyutor ay mas malamang na sumubok kapag nakakaranas ng mga posibleng sintomas.

| “ | Well, I suppose, ako personally, I think naintindihan ko [kung kailan magpa-test]. Bagaman sa palagay ko ay may ilang pagkalito sa mga sipon, trangkaso, lahat ng mga bagay na maaaring magkaroon ng mga katulad na sintomas."

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

Ang mga pagbabago sa opisyal na patnubay ng gobyerno ay nagdulot ng pagkalito sa mga tao tungkol sa kung kailan sila magsusuri at kung gaano katagal nila kailangang mag-self-isolate pagkatapos ng isang positibong pagsusuri. Ang pagkalito na ito ay pinalala ng iba't ibang mga diskarte sa iba't ibang mga bansa ng UK.

| “ | Sa una ay talagang malinaw at lahat ay nasa itaas nito sa aking […] ospital, at pagkatapos […] Sa tingin ko nagsimulang magbago ang mga patakaran at naging napakalabo […] Kailangan kong palaging […] mag-check online o magtanong sa trabaho, 'Ano ang sitwasyon ngayon? Magsusubok ba ako o hindi?' […] Sa palagay ko [ito] ay nagiging mas nakakalito habang tumatagal.”

– Taong nagtatrabaho sa pangangalagang pangkalusugan at panlipunan |

Nagkaroon din ng ilang pagkalito tungkol sa kung paano naiiba ang mga contact tracing app sa iba pang mga app na inilunsad noong panahong iyon upang suportahan ang mga paghihigpit sa Covid-19, halimbawa, isang app sa Scotland upang tumulong sa mga kahilingan sa parmasya, at kung paano gumagana ang iba't ibang system sa mga hangganan. Iminungkahi ng ilang kontribyutor na maaaring mayroong isang sistema para sa buong UK.

| “ | Masasabi ko lang na tila maraming apps, sabay-sabay. At maliban kung alam mo kung ano ang iyong ginagawa ay madaling mawala ng kaunti at gumamit ng mali gaya ng ilang beses kong ginawa.”

– Taong nakakuha ng suporta sa kalusugan ng isip |

| “ | Kinailangan kong maglakbay sa Scotland ng ilang araw para sa trabaho (ang aming punong tanggapan ay nasa Edinburgh) at nalaman kong ang mga QR code ng NHS app/government Covid app ay iba sa itaas. I find it wild na walang standardized system para sa UK."

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

Ang ilang mga nag-ambag – lalo na ang mga matatandang nag-aambag at/o ang mga hindi kasama sa digital na paraan – ay nag-ulat na nalilito kung paano mag-access at gumamit ng mga app, na naging dahilan ng kanilang pagkabalisa. Halimbawa, nag-download ng app sa pagsubaybay sa contact ang isang contributor na may dati nang kundisyong pangkalusugan (na hindi rin kasama sa digital), ngunit hindi sigurado kung paano ito gumagana. Ang pagtanggap ng mga abiso ay nagparamdam sa kanila ng pagkabalisa at sa ilang mga kaso ay lubhang nababalisa.

| “ | Mayroon akong app sa telepono...ping, ping, at iniisip ko, 'Bakit ako pini-ping?' At pagkatapos ay lalabas ito...may nakahuli sa [Covid-19] sa iyong lugar...at iniisip ko, 'Oh, kumukurap na impiyerno.'...tinanggihan ko ito. Pero iniisip ko, 'Oh my God, oh my God, papalapit na, papalapit na.'”

– Taong digital na hindi kasama |

Mas partikular, narinig namin na madalas na hindi alam ng mga tao kung ano ang gagawin kapag nakatanggap sila ng notification ng isang contact. Lalo itong nakakalito kapag mahirap matukoy kung kailan ginawa ang contact, o kapag may nakakatanggap ng maraming notification.

| “ | Sa palagay ko sinabi nito, 'Maaaring nakipag-ugnayan ka.' Masyadong malabo…kung may kakilala ako sa opisina na [parang] siguradong may Covid, mas gusto kong [mag-isip], 'Well, siguro kailangan kong mag-test.'...[pero] parang hindi masyadong nasusukat ng siyentipiko."

– Taong nagtatrabaho sa pangangalagang pangkalusugan at panlipunan |

Habang nagpapatuloy ang pandemya, nalilito ang ilang tao kung gaano katagal nila kailangang ihiwalay ang sarili pagkatapos nilang magkaroon ng abiso sa pakikipag-ugnayan., ano ang patnubay kung mayroon na silang Covid-19 o nabakunahan na, at ano ang magiging parusa kung hindi nila sinunod ang patnubay.

| “ | Sa palagay ko kung mayroong milyun-milyong tao ang gumagamit nito [ang contact tracing app], marahil ay wala lang itong kapasidad na, uri-uriin, i-update ito at maging mas may kaugnayan o indibidwal sa tao kung ipinakita nila-, tulad ng ganap na nabakunahan ako...kaya sinasabi nito na kailangan ko pa ring mag-self-isolate, at noong pumunta ako sa website sinabi nito, 'Hindi, hindi mo kailangan mag-self-bakuna'

– Zero-hours contract worker |

Narinig din namin na ang pagbabago ng mga alituntunin tungkol sa mga panahon ng pag-iisa sa sarili ay nagdulot ng hindi katiyakan ng mga tao habang nagpapatuloy ang pandemya tungkol sa mga panuntunang ipinatupad sa anumang oras.4 Halimbawa, ibinahagi ng ilan kung paano hindi nila naunawaan kung bakit patuloy na nagbabago ang bilang ng mga araw para sa pag-iisa sa sarili, sa kabila ng pagiging parehong virus. Bilang resulta, maraming nag-ambag ang nagsabing nagpasya silang gawin ang sa tingin nila ay ang "tama" na bagay sa bandang huli ng pandemya, ito man ay naaayon sa mga panuntunan sa pag-iisa sa sarili o hindi. Ang iba ay nagpasya na tapusin ang mga panahon ng pag-iisa sa sarili pagkatapos ng negatibong pagsubok bagama't sila ay nasa loob pa rin ng inirekumendang timeframe para sa pag-iisa sa sarili.

| “ | Buweno, ang bagay na tumatak sa aking isipan ay, bumalik sa pagkalito muli, kung bakit 14 na araw sa simula, at pagkatapos ay malinaw na bumaba ito sa 5 araw, at naaalala kong naisip ko noong panahong iyon, 'Alinman sa napakalaking overdone natin ang pag-iisa sa sarili sa simula, at hindi na natin kailangan na gawin ito sa loob ng 14 na araw, o kung saan ang mga tao ay lumalabas na ngayon pagkatapos ng 5 araw, mayroon pa rin silang potensyal na pag-iwas sa sarili. sa mga tao.' Kaya lang, hindi ko naramdaman na mayroong [isang] malinaw na paliwanag kung bakit ang bilang ng mga araw ay nabawasan nang husto.”

– Taong nagtatrabaho sa mga bata |

| “ | Ang patnubay ay minsan ay hindi maliwanag at hindi malinaw o mahigpit - ang mga may sakit ay dapat na sinabihan noong Enero/Pebrero 2020 na ihiwalay ang sarili - at ginawa ng kaso na kung hindi nila gagawin, ang bansa ay magsasara."

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

Ang pagtatapos ng mass testing ay nagpapataas din ng kalituhan para sa ilan.5 Nadama ng ilang kontribyutor na ang pagpapahinga ng mga kinakailangan sa pagsubok sa iba't ibang yugto ng pandemya ay tila hindi naaayon sa mga naunang kinakailangan sa pagsubok.

| “ | Noong napakataas pa ng mga impeksyon, mayroong […] malinaw na mga panuntunan, higit o hindi gaanong malinaw na ipinapahayag. Ito ay naging napakalinaw, nang ang pandemya ay medyo huminto […] ang rekomendasyon na ang pagsusuri ay hindi na kailangan pa [kahit] kung mayroon kang mga sintomas ay labis na nakakalito, pagkatapos naming [na] sinabihan sa loob ng dalawang taon na dapat kang magpasuri at manatili sa bahay.

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

- Ang mga pangunahing uri ng contact tracing na ginagamit ng mga contributor ay ang contact tracing app. Tatlong Covid-19 contact tracing mobile app ang binuo para sa iba't ibang rehiyon ng UK: 'NHS COVID-19' para sa England at Wales, 'StopCOVID NI' para sa Northern Ireland at 'Protektahan ang Scotland' para sa Scotland.

- Ang mga panahon ng paghihiwalay ay madalas na nagbabago sa buong pandemya sa England, na nag-iiba mula 14 na araw (Marso 2020) hanggang 10 araw (Disyembre 2020), pagkatapos ay 7 araw (Disyembre 2021 – nakadepende sa dalawang negatibong LFT) at kalaunan ay nabawasan sa 5 araw (Enero 2022). Iba't ibang panuntunan ang inilapat kung nakipag-ugnayan ka sa isang taong nagpositibo sa Covid-19 (kadalasan ay kinakailangang ihiwalay ang sarili para sa isang partikular na panahon mula sa petsa ng kanilang positibong pagsubok). Ang mga pagbubukod ay ginawa sa ibang pagkakataon kung ikaw ay nabakunahan, o ang isang confirmatory PCR test ay negatibo. Ang mga pagbabago sa mga panuntunan ay nangyari sa magkakaibang panahon sa apat na bansa.

- Ang lahat sa England ay inalok ng access sa dalawang beses lingguhang mabilis na pagsusuri para sa Covid-19 mula 9 Abril 2021 sa pagpapalawak ng mass asymptomatic testing program ng gobyerno. Kilala ito bilang universal testing offer (UTO). Ang panahon ng UTO ay tumagal hanggang sa katapusan ng Marso 2022. Kasama ng ilang iba pang mga patakaran sa Covid-19, huminto ito habang ipinakilala ng gobyerno ng UK ang 'Pamumuhay sa COVID-19' diskarte.

3. Mga Enabler: Ano ang nakatulong o naghikayat sa mga tao na lumahok sa pagsubok, pagsubaybay sa pakikipag-ugnayan at pag-iisa sa sarili? |

|

Ang kabanatang ito ay nagdedetalye ng mga salik na nakatulong o nagbigay-daan sa mga tao na lumahok sa pagsubok, pagsubaybay sa pakikipag-ugnayan at pag-iisa sa sarili. Inilalarawan nito ang mga enabler na ito at nagbibigay ng mga halimbawa kung saan at paano nila naiimpluwensyahan ang mga pag-uugali sa panahon ng pandemya. Ang kabanata ay nagtatapos sa mga pagmumuni-muni ng mga nag-aambag tungkol sa Nakapirming Mga Paunawa sa Parusa na nasa lugar.

Protektahan ang mga taong pinapahalagahan nila

Tinukoy ng mga kontribyutor na narinig namin mula sa isang pangkalahatang tungkulin na sundin ang patnubay ng pamahalaan upang protektahan ang kanilang mga sarili at ang mas malawak na populasyon, partikular na ang mga taong mahina.

Ang pakiramdam ng moral na obligasyon o 'konsensya' ay isang matibay na dahilan para sa mga tao na subukan, makisali sa pagsubaybay sa pakikipag-ugnayan at/o paghiwalay sa sarili kapag naramdaman nilang kailangan nila, upang 'gawin ang tamang bagay' at upang matiyak na ginagampanan nila ang kanilang bahagi sa paglimita sa paghahatid.

| “ | Hindi ako [...] isang rule-breaker, [...] Sinusunod ko ang lahat ng mga patakaran, kaya lahat ako ay para sa pagsubok, upang [...] mabawasan ang panganib ng pagkalat nito."

– Tagapag-alaga |

| “ | Kung mayroon akong Covid, ayaw kong ipasa ito sa ibang tao, kaya kung ang pagsasabi ko ng 'I've been somewhere' ay sapat na upang maiwasan ang ibang tao na mahuli ito, kung gayon iyon ay sapat na para sa akin."

– Taong may pangmatagalang pisikal na kondisyon sa kalusugan |

Para sa ilang mga tao na aming narinig mula sa, ang moral na obligasyon na protektahan ang iba ay sumalungat sa kanilang sariling pagnanais para sa kalayaan sa paggalaw (higit pang detalye tungkol dito sa seksyong 'Mga Kalayaan' sa ibaba), na lumilikha ng dilemma

| “ | The conscience kicking in. Ngunit sa lahat ng ito, ako, parang, ayoko mag-test, dahil kung mag-positive ako, hindi ko magagawa ang ilang bagay, alam mo, ito ay isang beses na wala tayo sa isang lockdown, at kailangan mong [self-] ihiwalay at iba pa. At ako ay nasa isang matinding salungatan sa moral kung uunahin ko ba ang aking sarili at hindi subukan, o talagang inuuna ko ba ang lahat at subukan para sa kanilang kapakinabangan.

– Zero-hours contract worker |

Ang mga nag-aambag na may mga responsibilidad sa pag-aalaga ay nakadama ng pagkabalisa sa panahon ng pag-iisa sa sarili. Namuhay sila na may malalim na pag-aalala at pakiramdam ng responsibilidad tungkol sa hindi pagpasa o kung hindi man ay hayaan ang kanilang mga mahal sa buhay na magkaroon ng Covid-19. Madalas nilang inilarawan kung gaano palagian at mahigpit ang pagsunod nila sa mga panuntunan sa pag-iisa sa sarili upang mabawasan ang panganib na ito, ngunit kung paanong ang pakiramdam ng pagkabalisa at pagkakasala tungkol sa kung ano ang ibig sabihin nito para sa kanilang mahal sa buhay ay napakahirap na makayanan. Partikular na naapektuhan sa ganitong paraan ang mga nag-aambag na naninirahan sa mga multi-generational na sambahayan at may mga kamag-anak na mahina sa klinikal.

| “ | Pangunahin, ito [pagsunod sa mga alituntunin sa pag-iisa sa sarili] ay dahil ayaw kong patayin sila [mga magulang ng nag-aambag]...kailangan mo lang maging makatotohanan, at kailangan mong protektahan ang mga tao. Ginagawa namin ang sinabi sa amin at iyon lang, alam mo ba?"

– Taong naninirahan sa isang multi-generational na sambahayan |

Sa ilang komunidad ng mga manlalakbay, sinabi ng mga kontribyutor na sumunod sila sa mahigpit na mga panuntunan sa pag-iisa sa sarili sa site anuman ang isang tao sa kanilang komunidad ay nagpositibo sa virus o nagkaroon ng mga sintomas. Nangangahulugan ito na kapag ang isang tao ay nagkasakit ng Covid-19, mayroon nang mga patakaran at gawi na pinadali ang isang mataas na antas ng pag-iisa at proteksyon sa sarili.

| “ | … [W]e ay walang darating sa site. Kaya naman, sa loob ng bawat sambahayan, ang bawat isa ay nanatili sa kanilang sariling sambahayan. Pwede tayong tumayo sa labas, may kalye na magkaharap lang, pwede kang mag-chat. Alam mo, huwag lumabas, makipag-chat sa isa't isa, ipaalam sa mga tao kung ano ang iyong nararamdaman doon. Pero wag ka sumama, wag kang lalabas, wag kang dumalaw. Kaya, noong mga oras na kailangan mong gawin iyon [mag-isa sa sarili], iyon ay pinanatili sa loob ng mga batas nang maayos sa loob ng komunidad.

– Taong mula sa pinagmulang etniko ng Roma |

Pangungulila

Para sa mga nawalan ng mga mahal sa buhay sa panahon ng pandemya at hindi nagawang magdalamhati o magdalamhati sa iba, ang emosyonal na pinsala ay napakalaki. Ang pagdanas ng pangungulila ay nagkaroon ng malaking epekto sa lawak kung saan naramdaman ng ilang tao na sumunod sa mga alituntunin sa pag-iisa sa sarili. Ibinahagi ng ilan kung paano ang ibig sabihin ng kanilang pagkawala ay nakita nilang mahalaga ang pagsunod sa mga alituntunin at madalas na mahigpit na nakikipag-ugnayan sa kanila.

| “ | Sineseryoso ito ng aking pamilya [mga alituntunin sa pag-iisa sa sarili], dahil nawalan kami ng isang taong malapit sa amin nang maaga sa pandemya, literal noong linggo ding iyon na inanunsyo ng lahat na manatili sa bahay. Kaya, oo, siniseryoso namin ito mula sa simula.

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

Sinabi rin sa amin ng mga tao kung paano sila napag-isipan ng mga alituntunin sa pag-iisa sa sarili at isaalang-alang ang kanilang paggawa ng desisyon noong binisita nila ang isang mahal sa buhay sa ospital na namamatay. Nangangamba sila kung ang isang mahal sa buhay ay namatay pagkatapos ng pagbisita at sinabihan silang ihiwalay ang sarili, na hindi sila pisikal na naroroon upang aliwin ang kanilang pamilya sa panahon ng kanilang kalungkutan. Naniniwala sila na ito ay magkakaroon ng pangmatagalang at traumatikong epekto sa kanila at sa proseso ng pagdadalamhati ng kanilang pamilya. Ang ilan sa mga narinig namin mula sa na nawalan ng mga mahal sa buhay ay natagpuan din ang kanilang sarili na nahaharap sa napakahirap na suliranin ng pagpapasya kung ang panganib ng hindi pagsunod sa mga alituntunin sa paghihiwalay sa sarili ay higit pa sa mga potensyal na epekto ng pagsunod sa kanila.

| “ | Pinayuhan kami na isang miyembro lang ng pamilya ang maaaring bumisita sa ward [para makita ang kanyang 94-anyos na lola na may dementia, COPD at Leukemia na naghihingalo] na nakasuot ng full personal protective equipment (PPE), at kailangan nilang ihiwalay ang sarili pagkatapos. Ang nanay at tiyuhin ko ay clinically vulnerable, at ang aking kapatid na babae ay nag-iisa na sa sarili, kaya nag-iwan sa akin ng dilemma kung bibisita, alam na kung siya ay namatay, hindi ko magagawang yakapin ang aking 7-taong-gulang na anak na babae sa loob ng dalawang linggo, habang naranasan niya ang kanyang unang pangungulila.

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

kwento ni RyanIbinahagi sa amin ni Ryan ang kanyang karanasan sa pag-iisa sa sarili noong ang kanyang ama ay tumatanggap ng end of life care sa ospital. Si Ryan ay may mga sintomas ng Covid-19 noong panahong iyon at hindi siya pinayagang bisitahin siya, sa halip ay kailangang makipag-ugnayan sa pamamagitan ng telepono. Habang siya ay nagbubukod sa sarili, ang ama ni Ryan ay malungkot na namatay at siya ay naiwang mag-isa na nagdadalamhati, na masama pa rin ang pakiramdam. Kinailangan din niyang gumawa ng funeral arrangement dahil mahirap ang kanyang ina at hindi na kaya. |

|

| “ | Namatay ang aking ama. Ako ay nag-iisa, may sakit at walang makitang sinuman.” |

| Nagpasya siyang ayusin ang isa pang pagsusuri sa Covid-19 sa pamamagitan ng telepono pagkatapos ng dalawang linggong pag-iisa sa sarili. Gayunpaman, ang kanyang resulta ay isang 'false' positive. Nakaramdam siya ng galit na hindi siya nalaman na ito ay isang posibilidad pagkatapos kumuha ng pagsusulit sa loob ng 90 araw pagkatapos mahawa ng virus. Nangangahulugan ito na kinakailangan siyang mag-self-isolate para sa karagdagang 10 araw, bagama't walang sintomas. Ilang beses siyang tumawag sa 119 upang tanungin ang kanyang resulta ngunit sinabihan siyang kailangan pa niyang mag-self-isolate.6 | |

| “ | Tumawag ako sa 119. Karaniwang sinasabi sa akin na walang kabuluhan ang pagtatalo at kailangan kong [mag-isa] na ihiwalay.” |

| Emosyonal at praktikal na naapektuhan si Ryan ng naramdaman niyang isang malaking kawalan ng pag-unawa sa kanyang sitwasyon mula sa mga taong nakausap niya sa 119, lalo na sa panahon ng pagdadalamhati. | |

| “ | tawag ko ulit. Sinabi sa akin na walang pagpipilian kundi ang [self-] ihiwalay. Mayroon na akong mga papeles na ginagawa para sa libing at pagpaparehistro ng pagkamatay ni tatay, na halos lahat ay hindi ko makumpleto dahil hindi ako makapunta sa bahay ng aking mga magulang upang hanapin ang impormasyon. Gusto kong puntahan si tatay sa funeral parlor. hindi ko kaya. Kailangan kong maglipat ng pera para bayaran ang libing. hindi ko kaya. Gusto kong suriin ang kalagayan ng aking ina dahil natagpuan ang isang lugar sa isang angkop na tahanan ng pangangalaga. Hindi ko kaya.” |

Mga kinakailangan

Inilarawan ng mga nag-aambag na nagtatrabaho sa isang hanay ng mga sektor kung paano naging bahagi ang regular na pagsusuri sa kanilang mga panuntunan at kinakailangan sa lugar ng trabaho sa panahon ng pandemya, may mga sintomas man o wala ang mga tao. Kasama dito ang pagkakaroon ng pagsubok sa isang lingguhan/dalawang beses-lingguhang batayan o bago ang bawat shift. Inilarawan ng ilang kontribyutor kung ano ang naramdaman nila na ang pagsubok sa trabaho ay nakatulong upang gawin itong mas ligtas na kapaligiran.

| “ | May patakaran talaga ang lugar ng trabaho ko, kaya kailangan naming mag-test every week.”

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

| “ | Ang trabaho ay isang […] pangunahing salik para sa akin […] nagtatrabaho sa A&E, kailangan naming subukan […] linggu-linggo […] gamit ang mga lateral flow […] madali lang. Malinaw na iyon ay para sa kaligtasan ng mga pasyente at sa aking [sariling], at […] mahalaga na patuloy kaming sumubok para maprotektahan din ang aming mga pamilya.”

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

Ang isang karagdagang dahilan para sa pagsubok para sa ilang mga manggagawa sa mga tungkulin sa pamamahala ay isang pagnanais na magtakda ng isang halimbawa para sa iba pang mga kasamahan.

| “ | It [the discomfort] did put me off but at the same time, alam kong kailangan kong gawin ito. Kinailangan kong maging isang halimbawa rin, bilang tagapamahala, […] sa aking mga tauhan, kaya walang paraan na ako [magiging] mangaral, 'Gawin mo ito, gawin mo ito,' at hindi gawin ito [rin]."

– Taong may kahirapan sa pagbasa |

Nakatulong din ang pagsubok na maibsan ang mga takot tungkol sa paglalagay ng panganib sa iba sa pamamagitan ng pagpasa ng virus sa mga kasamahan o miyembro ng pamilya.

| “ | Mas malamang na mag-test ako dahil […] talagang natatakot akong makuha ito. […] Nasa placement ako nang malaman kong may Covid ako […]. Nagkaroon ako ng mataas na temperatura sa buong araw, pagpapawis, pananakit ng ulo […] isang oras bago natapos ang aking shift […] Nagawa ko na ang pagsusulit at ito ay positibo, kaya malinaw na nagdudulot din iyon ng pagkataranta sa mga tao na nagtatrabaho ka […] na parang, 'Buong araw na kasama kita.' […] nakakaramdam ka rin ng pagkakasala […], 'Inilagay ko sa panganib ang ibang tao'.”

– Taong nagtatrabaho sa pangangalagang pangkalusugan at panlipunan |

Para sa maraming nag-aambag na nakikipag-ugnayan nang harapan, sa propesyonal man o personal na kapasidad, sa mga taong mas mahina sa mga epekto ng virus, ang regular na pagsusuri ay inilarawan bilang isang mahalagang bahagi ng kanilang personal na tungkulin ng pangangalaga. Ito ay partikular na ang kaso para sa mga taong may mga responsibilidad sa pag-aalaga, o kung sino ang bumibisita sa mas matanda o mahinang kamag-anak. Inilarawan ng mga propesyonal sa pangangalagang pangkalusugan at panlipunan ang regular na pagsusuri bilang bahagi ng kanilang legal na tungkulin sa pangangalaga.

| “ | Pakiramdam ko ay tungkulin ko ng pangangalaga, sa mga pasyente at parmasya. […] nandoon kami na nag-aalok ng serbisyo na palagi naming inaalok, at pakiramdam ko ay tungkulin ko lang ito […] sa moral, […] kung mayroon akong Covid at hindi pa nagsusuri, at ipinasa iyon sa, sabihin nating, isang 90-taong-gulang na pasyente na pumasok para sa kanyang gamot, talagang malungkot ako […] hindi man lang sumagi sa isip ko […] na hindi magpasuri.' Dahil [naramdaman ko] na dapat akong sumubok."

– Taong nagtatrabaho sa pangangalagang pangkalusugan at panlipunan |

| “ | Dahil naging tagapag-alaga ako sa buong buhay ko, nakasanayan ko na […] na parang nauuna siya [ang aking ina], […] parang kung may mangyari sa aking ina dahil lagi siyang nasa bahay at nagbubukod. Hindi ko alam, kung hindi ako naging sapat na mapagbantay upang makilala na ang sintomas na ito ay maaaring nauugnay sa Covid at hindi kumuha ng pagsusulit, at pagkatapos, bilang isang resulta nito, hindi [pag-iisa] sa sarili at pagkatapos ay nasa paligid niya, at kailangan niyang makuha ito, oo, makaramdam ako ng pagkakasala na ako ang naging sanhi nito.

– Tagapag-alaga |

Kwento ni MichaelSi Michael ay isang estudyante at nagtrabaho sa isang supermarket noong panahon ng pandemya. Siya ay isang kabataan at sa kanyang unang taon sa unibersidad nang magsimula ang pandemya. Inilarawan niya kung gaano kalaki ang pandemya para sa kanya, dahil sa mga epekto sa kanyang pag-aaral, trabaho, at pamilya. Ang supermarket kung saan siya nagtrabaho ay may sariling internal testing system, na sinundan ni Michael. Nagtatrabaho sa isang tindahan kung saan siya nakipag-ugnayan sa mga miyembro ng publiko, naniniwala si Michael na mahalaga ang pagsubok upang maprotektahan ang iba. |

|

| “ | Malaking bahagi niyan ang trabaho, in terms of going to work, I didn't want to put anyone else at risk, especially the job that I was doing is, well, called a key worker, I never like to say it because in compared to the NHS, I was just working in a shop. |

| Nag-aalala rin si Michael para sa kanyang mga kapamilya. Siya ay may mga kamag-anak na naospital dahil sa Covid-19 at inilagay sa mga bentilador, na nakakaranas ng matinding paghinga. Ang kanyang ina ay mayroon ding pangmatagalang kondisyon sa kalusugan at nagkasakit nang malubha nang siya ay magkasakit ng Covid-19. Nag-aalala si Michael na kung pupunta siya sa ospital, ang kanyang kalusugan ay malalagay sa panganib dahil sa mas mataas na pagkakataon na magkaroon ng impeksyon. Nadama ni Michael na mahalagang magpasuri hindi lamang sa mga tuntunin ng kanyang sariling peligro para sa Covid-19, ngunit bilang isang paraan ng pagpapagaan ng panganib para sa ibang mga tao. Mahalaga sa kanya na maging maingat at magsuri nang madalas, sa halip na ipagsapalaran na mahawahan ang kanyang mas mahinang mga miyembro ng pamilya. | |

| “ | Wala akong pinagbabatayan na mga kondisyon sa kalusugan sa puntong iyon, ngunit ang aking ina ay nagkaroon at ang aking [mga kamag-anak] ay nagdurusa. Tulad ng, walang katuturan para sa akin na ipagsapalaran ito […] mas madaling sundin kung ano ang ipinayo kaysa subukan at maging napakatalino at pagkatapos ay potensyal na patakbuhin ang panganib kung makatuwiran iyon.” |

Katulad nito, ipinaliwanag ng ilang kontribyutor kung paano sinusuportahan ng kanilang mga lugar ng trabaho ang mahigpit na pagsunod sa mga itinakdang panahon ng pag-iisa sa sarili. Inilarawan ng mga taong nakausap namin na nakakaranas sila ng mas mababang antas ng stress kapag nasunod nila ang mga protocol nang walang panggigipit mula sa kanilang mga tagapag-empleyo, dahil alam nilang binigyan sila ng kapangyarihang maghiwalay sa sarili nang walang anumang negatibong kahihinatnan na nauugnay sa trabaho.

| “ | Yes I did, because work was quite strict, obviously if you have Covid, don't come in. Kasi, we need everyone we can. Oo, nanatili ako sa bahay, hindi ko na matandaan kung ilang araw ang iminungkahi nila, ngunit ginawa ko ang buong panahon. Kahit na bumuti na ang pakiramdam ko, naghintay ako hanggang sa mag-negative ako."

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

Access sa suporta

Ang pag-access sa suporta ay susi para sa ilang mga tao na ma-access ang pagsusuri sa PCR. Kasama sa suporta ang tulong sa pag-unawa sa proseso, pag-book ng mga appointment o paghahatid sa bahay, pagdalo sa mga appointment o pagbabalik ng mga pagsusulit at pagtanggap ng mga resulta. Iba-iba ang antas ng suportang kailangan ng mga tao: ang ilan ay nangangailangan ng tulong sa isang elemento ng proseso ng pagsubok, halimbawa, paghahanap at paggamit ng mga online booking form, samantalang ang iba ay ganap na umaasa sa tulong sa pag-book ng mga appointment, paglalakbay sa mga test center at pag-access ng mga resulta ng pagsubok.

| “ | [Ang aking mga kamag-anak] ay matatanda na at walang sinuman sa kanila ang marunong bumasa o sumulat, wala silang mga telepono […] Kaya, ginawa ko iyon: tumawag ako, nakipag-appointment […] dinala sila [para sa pagsusulit...] at tiniyak na nasa kanila [ng staff] ang aking email at numero [para sa mga resulta].”

– Taong mula sa pinagmulang etniko ng Roma |

Mga organisasyong pangkomunidad na nakikipagtulungan sa mga komunidad ng Gypsy at Traveler, mga taong may mababang antas ng literacy at mga taong ang unang wika ay hindi Ingles na nag-aalok ng 1:1 na suporta upang ma-access ang mga pagsubok. Gumawa at nagbahagi ng mga video ang ilang miyembro ng komunidad upang ipaliwanag ang pangkalahatang pagsubok, pagsubaybay at paghiwalayin ang mga kinakailangan.

| “ | Ang lahat ay sakop sa paligid ng Covid at ibinahagi. Lahat ng nanggaling sa gobyerno ay ibinahagi, kaya tuwing may mga guide rules na inilalagay, gagawa ako ng live na video at i-share ito. Kaya, alam mo, at kilala ko ang mga taong hindi marunong bumasa o sumulat, at alam kong hindi magiging interesado ang mga nakababatang bata sa kung ano ang isusulat ko doon. Kaya, kung gumawa ako ng live na video at ibinahagi ito sa aking WhatsApp at ibinahagi ito sa aking Facebook, maaaring isang minuto lang ito.”

– Tao mula sa komunidad ng Manlalakbay |

Katulad nito, ang pag-access sa suporta mula sa mga kaibigan at miyembro ng pamilya sa mga panahon ng pag-iisa sa sarili ay mahalaga sa pagpayag sa mga tao na mag-isa. Nakatulong ang mga impormal na network ng suporta sa pamamagitan ng paghahatid ng mga mahahalaga at pagbibigay ng emosyonal na suporta sa mga nagbubukod sa sarili. Ang ganitong uri ng suporta ay kadalasang katumbas ng mga nag-aambag kung saan magiging napakahirap na ihiwalay ang sarili kung hindi man.

| “ | I-text ko ang aking kapatid na babae at kukunin niya ang kailangan ko at iniwan ito sa harap ng pintuan, at pagkatapos ay ililipat ko ang pera sa kanyang bangko para sa dinala niya sa akin, kaya mabuti iyon. At ganoon din ang ginawa ko para sa kanya. Para sa nanay ko, kapag nagtatrabaho ako, kukuha ako ng mga mensahe at ihahatid ito sa kanyang pintuan para sa kanya. So, we helped each other out as a family, especially if you're isolating.”

– Clinically vulnerable na tao |

Kadalasan ang lakas ng impormal na suporta sa pamamagitan ng mga kaibigan at pamilya ay nangangahulugan na ang pormal na suporta ay hindi kailangan upang ihiwalay ang sarili. Nangangahulugan ito na ang ilang mga kontribyutor ay hindi naghanap ng mga pormal na serbisyo ng suporta kaya hindi nila alam ang mga ito.

| “ | Hindi ko kailangang gamitin ito, ngunit alam ko na […] nagpatakbo ng iba't ibang mga scheme sa panahon ng lockdown. Pagsusuplay-, pagdadala ng mga panustos sa mga pamilyang nagbubukod at kailangan, ngunit tulad ng sinasabi ko, hindi ko kailangang gamitin ang mga ito sa aking sarili.”

– Manggagawa sa paggawa |

Ang patuloy na suporta ng espesyalista sa bahay sa panahon ng pandemya ay nakatulong sa ilang taong may mga kondisyon sa kalusugan na ihiwalay ang sarili. Ang mga nag-aambag na ito ay nagsalita tungkol sa kung paano ang pagpapatuloy ng suportang ito, madalas sa malayo, ay nagpapahintulot sa kanila na sumunod sa mga alituntunin sa pag-iisa sa sarili nang hindi bumababa ang kanilang kalusugan.

| “ | Sa tingin ko karamihan sa mga nauugnay na impormasyon ay dumarating sa pamamagitan ng [isang] consultant sa [ospital]. Iyon at siya [ang kanyang asawang may kanser] ay may isang nakatalagang nars doon. Tumatawag siya ng dalawa o tatlong beses sa isang linggo, para lang masigurado na maayos ang [kanyang asawa], at maayos ang mga bagay-bagay...mayroon kaming backup na maaari naming kausapin, at anumang mga tanong namin, nasasagot nila […] gaya ng sinabi ko kanina, na tiniyak namin na alam namin ang mga patakaran na dapat naming mahigpit na sundin sa panahong iyon.”

– Miyembro ng pamilya o tagasuporta ng isang tao na kinakailangang ihiwalay ang sarili |

Narinig namin mula sa iba ang tungkol sa pagiging kasangkot sa komunidad na nagbibigay ng suporta sa mga panahon ng pag-iisa sa sarili. Nag-iiba-iba ito sa iba't ibang lugar depende sa mga kasalukuyang network o suportang naka-set up sa panahon ng pandemya, na kung minsan ay nasasangkot ang lokal na pamahalaan. Naalala ng ilan ang paggamit ng mga app at social media upang malaman kung sino ang nangangailangan ng mga mahahalagang bagay sa panahon ng pag-iisa sa sarili upang makatulong ang mga tao sa komunidad na maibigay ang mga ito. Ito ay madalas na impormal at lumitaw nang maaga sa pandemya para sa mga kinakailangang ihiwalay ang sarili.

| “ | Kaya, mayroon kaming isang pangkat ng Covid sa WhatsApp na ginawa ng aming lokal na konseho, na kinuha ang bawat kalye at itinakda ang lahat ng ito upang ang lahat na online ay malinaw na may kontak na iyon. At, sinubukan nilang ipaalam sa mga tao kung aling mga tahanan ang walang access para matulungan sila ng mga lokal na tao kung wala silang access [sa mga mahahalaga].”

– Clinically vulnerable na tao |

Ang mga lokal na organisasyon ng komunidad ay may mahalagang papel sa pagbibigay ng direktang suporta sa ilan na nagbukod sa sarili, na partikular na mahalaga para sa mga sambahayang madaling maapektuhan ng klinikal at sa mga nakatira sa liblib o kanayunan. Gayunpaman, nakadepende ito sa perang magagamit, nililimitahan ang bilang ng mga tao na nasuportahan sa ganitong paraan.

| “ | Ang simbahan ko, [pangalan ng simbahan], talagang sinusuportahan nila ang marami sa aming mga kongregasyon na baka may sakit ang kanilang mga anak, at hindi sila pinapayagang magtrabaho o nasa isang tiyak na lugar. Nagde-deliver talaga sila ng mga pagkain na kailangan nila linggu-linggo. Kaya, ito ay isang napakagandang tulong para sa ilan sa aking mga miyembro ng simbahan. Bagaman, kung wala silang sapat na badyet upang suportahan ang maraming indibidwal na nangangailangan ng tulong na iyon, magagawa lang nila ang maliit na magagawa nila.

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

| “ | Noong Marso 2020, nagpulong ang mga pinuno ng relihiyon, mga konsehal ng parokya, mga lokal na GP at mga may-ari ng negosyo upang talakayin kung paano masusuportahan ng ating nakahiwalay na komunidad sa kanayunan ang mga residente sa nayon at mga nasa labas na bukid at tahanan. Mahigit 100 boluntaryo ang dumating at bawat isa ay binigyan ng 20 tahanan sa loob ng isang partikular na postcode upang suportahan. Naghatid sila ng mga postkard na may mga pangalan at mga detalye sa pakikipag-ugnayan sa bawat isa sa 20 tahanan na iyon at naghatid ng mga gamot at pamimili, naglalakad-lakad sa mga aso, nakipag-chat mula sa isang ligtas na distansya at sa ilang mga kaso ay nakipagkaibigan sa mga nakatirang mag-isa na kung hindi man ay hindi nakipag-ugnayan sa sinuman sa loob ng maraming buwan.

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

Kalayaan

Habang nagpapatuloy ang pandemya, ang pagnanais na makisali sa edukasyon at paglalakbay ay naging dahilan upang subukan ang ilan. Nagsalita ang mga tao tungkol sa kinakailangang magpasuri para makapag-aral sa kolehiyo at masuri ang kanilang mga anak para makapag-aral sila, gayundin ang mga legal na kinakailangan para makapagbigay ng negatibong PCR test para makapaglakbay sa ibang bansa.

| “ | Magbakasyon […] kailangan mong magsagawa ng mga pagsusuri sa PCR noong pumunta ka at pagkatapos ay pagbalik mo, kaagad […] noong nagsimula akong magbakasyon […] muli, [naaalala ko] na nagsimulang gumawa ng higit pang mga pagsusulit dahil lamang ito ay kinakailangan ng batas.”

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

Gayundin, narinig namin mula sa mga taong nagsabi sa amin na ang pagsubok ay may papel sa pakiramdam ng mga tao na mas may kakayahan at handang makihalubilo, at narinig namin mula sa mga taong sumubok sa buong pandemya para sa kadahilanang ito. Ito ay dahil ang pagsusuri ay nakita bilang isang paraan ng pagbabawas ng panganib ng pagkalat ng virus. Ang isang negatibong LFT ay nagbigay ng 'patunay' na ang isang tao ay ligtas na makihalubilo sa iba.

| “ | Mahusay iyon dahil mapapatunayan kong malusog ako […] para makapunta ako [sa…] mga lugar [tulad ng] mga nightclub, […] aking kolehiyo o kahit saan.”

– Taong ang unang wika ay hindi Ingles |

Ang pagsali sa contact tracing ay nadama din na isang mahalaga at kinakailangang hakbang para makihalubilo sa iba sa labas ng tahanan, lalo na sa paglabas ng lipunan sa lockdown at muling nagbukas ang mga cafe, bar at restaurant.

| “ | Ito ay isang paraan para makalabas ang mga tao. Pinayagan nito ang mga tao na lumabas, alam mo, 'mag-sign in at maaari kang magkaroon ng pagkain sa restaurant na ito'. Nangangahulugan ito na kung makipag-ugnay ka, maaari kang [mag-isa] na ihiwalay, at halos nagbigay ito sa iyo ng pag-uudyok na pumunta, 'Sa totoo lang, dapat akong gumawa ng isang pagsubok'."

– Taong nakakaranas ng kahirapan sa pananalapi |

Pagpapagaan ng takot

Sinabi sa amin ng mga nag-aambag na lumahok sila sa pagsubok sa panahon ng pandemya upang maibsan ang kanilang takot at pag-aalala tungkol sa pagkakaroon ng virus. Ito ay lalo na ang kaso sa simula ng pandemya dahil nakatulong ito sa pagkumpirma kung ang kanilang mga sintomas ay dahil sa Covid-19 at nabawasan ang mga takot tungkol sa kanilang sariling kaligtasan at ang panganib ng impeksyon.

| “ | Anumang oras na bumahing o uubo ka, […] parang, 'Kailangan ko ba ng pagsusulit? [...] Nagkaroon na ba ako ng Covid?' at pagsubok.”

– Taong nabubuhay na may Long Covid |

| “ | Sa tingin ko panic, alam mo, kung nakakatanggap ka ng text message na nagsasabi sa iyo na nakasama mo ang isang taong nasubok na positibo, awtomatiko mong iisipin, 'Oh Diyos ko, makukuha ko ito.' Kaya oo, lalabas ka at magpasuri para dito. Para sa akin personal, ito ay gulat.

– Taong nagtatrabaho sa pangangalagang pangkalusugan at panlipunan |

Ang mga pag-aalala ay mas matinding naramdaman ng mga nag-aambag na may mga kasalukuyang kondisyon sa kalusugan.

| “ | Ako ay nasa [isang] high-risk na grupo, kaya alam ko na kailangan kong sundin ang mga alituntunin at magpasuri. Ito ay isang no-brainer para sa akin.

– Miyembro ng komunidad na sumuporta sa mga tao na ihiwalay ang sarili |

Ang takot at pag-aalala tungkol sa pagkontrata ng Covid-19 ay iniugnay ng ilang kontribyutor sa coverage ng media at pag-uulat sa bilang ng mga namamatay. Para sa ilan, ang pag-uulat tungkol sa mga pagkamatay ay nakaimpluwensya sa mga tao na subukan. Higit pa rito, ang personal na pagkilala sa mga taong may malubhang sakit o namatay mula sa virus ay nangangahulugan na ang ilang mga nag-ambag ay nakaramdam ng higit na takot sa Covid-19 na isa pang dahilan upang subukan ito.

| “ | Sinubukan ko ang lahat, dahil […] ang aking tiyuhin ay pumasok sa ospital na may menor de edad na kondisyon sa puso [at…] nahuli si Covid at […] siya ay talagang namatay. […] Nawalan ako ng miyembro ng pamilya dahil dito, [kaya alam ko] hindi lang media hype […] ito ay totoo. Kaya, nagpatuloy ako sa pagsubok hanggang sa sinabihan kami na huwag […] Mayroon akong app sa aking telepono, at regular na nasubok, at ibinigay ang aking mga resulta.”

– Zero-hours contract worker |

Access at kaginhawaan

Mga pagsusuri sa PCR

Sa unang bahagi ng pandemya, ang mga pagsusuri sa PCR ay magagamit upang mag-book online o sa pamamagitan ng telepono at ang mga appointment ay nasa mga testing center. Ang mga pagsusuri sa PCR ay maaari ding matanggap sa pamamagitan ng koreo at gawin sa bahay.

Maraming kontribyutor na narinig namin mula sa naglalarawan ng isang diretso at mabilis na proseso sa pag-book ng mga appointment sa PCR test online o sa pamamagitan ng telepono, na nagbibigay-daan sa kanila na sumubok kapag naisip nilang kailangan nila. Lumilitaw na ang pinaghihinalaang kaginhawahan ay isang pangunahing enabler para sa mga taong nagpapasyang sumubok. Pagkatapos ibigay ang kanilang postcode, inalok sila ng pagpipilian ng mga test center na nakalista ayon sa kalapitan at nakapili sila ng maginhawang timeslot.

| “ | Napakadaling sundan […] literal mong ilagay ang iyong postcode, at […] ito ay magsasabing, [...] 'ito ay 1.1 milya ang layo, ito ay 3.5 milya ang layo...' […] pipili ka lang […] pagkatapos ay [piliin] ang oras na maaari mong ilabas […] ilagay sa iyong mga detalye, at iyon na."

– Nag-iisang magulang |

| “ | Nag-book ako ng Covid test na talagang mabilis at madali. Ang test center ay halos 20 minutong biyahe mula sa akin. […] Ang buong proseso ay talagang malinaw at mahusay na binalak.”

– Kontribyutor ng Every Story Matters |

Ang ilan sa mga nag-isip sa kanilang sarili na hindi gaanong marunong sa teknolohiya ay nagsabi na ang proseso ng online booking ay naging mas madali sa paglipas ng panahon, habang sila ay naging pamilyar at habang ang system ay nag-save at naalala ang mga personal na detalye.

| “ | Lahat ng ito ay online, na […] isang bagay na hindi namin pamilyar [...] nahirapan namin ito sa simula, ngunit pagkatapos ay nakuha namin ito."

– Taong naninirahan sa isang multi-generational na sambahayan |

| “ | Ang mas maraming pagsubok na ino-order mo[ed] mas madali ito dahil ito [ang sistema ng booking] ay mayroong lahat ng iyong impormasyon [naimbak].”

– Taong may kahirapan sa pagbasa |

Ang opsyong mag-book sa pamamagitan ng telepono ay nakatulong sa ilang tao na mapagaan ang mga hadlang sa literacy.

| “ | Kinailangan naming tumawag at humingi ng pagsusulit […Na-book ko ito sa pamamagitan ng telepono] dahil hindi ako masyadong magaling sa pagbabasa.”

– Taong may kahirapan sa pagbasa |

Maraming kontribyutor na bumisita sa mga PCR test center ang nagsabing maganda ang pagkakaroon ng appointment. Ang mga pareho o susunod na araw na appointment ay karaniwang ibinibigay para sa mga nagbu-book nang maaga, at ang maikling oras ng paghihintay ay nagpadali sa pag-access para sa mga pumapasok sa mga drop-in center. Ang mga oras ng pagbubukas ng mga test center ay nagbigay-daan din sa mga tao na dumalo sa mga appointment sa maginhawang oras.

| “ | Ang mga istasyon ng [pagsubok] ay bukas sa loob ng mahabang panahon sa araw. Kaya, sabihin […] ang mga sintomas [nagsimula] sa gabi, hindi mo na kailangang maghintay ng matagal upang pumunta at magpasuri, maaari kang makapasok sa […] 7:00 ng umaga kung gusto mo.”

– Nag-iisang magulang |

Bagama't naramdaman ng ilang nag-aambag na ang mas malalaking test center ay mas madaling ma-access dahil sa kanilang kapasidad, ang iba ay sadyang humingi ng appointment sa mas maliliit na test center at/o sa mas tahimik na mga oras upang mabawasan ang inaasahang paghihintay. Ang pagkakaroon ng isang pagpipilian at hanay ng mga sentro ay nagpadali sa mga tao sa paggawa ng mga desisyon na nababagay sa kanila. Ang ibang mga tao na aming narinig mula sa ay hindi nakaranas ng madaling pag-access sa mga test center at ang mga kuwentong ito ay makikita sa 'Barriers' chapter.