Mae rhai o'r straeon a'r themâu sydd wedi'u cynnwys yn y cofnod hwn yn cynnwys disgrifiadau o farwolaeth, profiadau bron â bod yn farw, esgeulustod, gweithredoedd o hepgor a niwed corfforol a seicolegol sylweddol. Gall y rhain fod yn ofidus. Os felly, anogir darllenwyr i geisio cymorth gan gydweithwyr, ffrindiau, teulu, grwpiau cymorth neu weithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol lle bo angen. Darperir rhestr o wasanaethau cymorth ar wefan Ymchwiliad Covid-19 y DU.

Rhagair

Dyma bedwerydd cofnod Every Story Matters ar gyfer Ymchwiliad Covid-19 y DU. Mae'n dwyn ynghyd y miloedd lawer o brofiadau a rannwyd gyda'r Ymchwiliad yn ymwneud â'i ymchwiliad i'r sector gofal.

Cyffyrddodd y pandemig â bywydau cynifer o bobl mewn gofal – y rhai sy'n derbyn gofal a chymorth, eu teuluoedd, gweithlu cartrefi gofal, gofalwyr cartref a gofalwyr di-dâl a oedd yn gofalu amdanynt. Ar draws y DU roedd profiadau'n amrywio. Mae'r cofnod hwn yn dwyn ynghyd y profiadau hynny, gan roi llais i'r rhai a fu fyw a gweithio drwyddo.

Clywsom am yr heriau dwfn a wynebodd pobl – teuluoedd wedi’u cadw ar wahân, staff gofal wedi’u hymestyn i’w terfynau ac anwyliaid yn marw mewn amgylchiadau torcalonnus. Siaradodd llawer o bobl am boen peidio â gallu dal llaw, rhannu cwtsh, neu ffarwelio’n iawn. I’r rhai a adawyd ar ôl, roedd y galar yn aml yn cael ei wneud yn anoddach gan y cyfyngiadau a oedd ar waith. Clywsom hefyd am garedigrwydd, ymroddiad ac eiliadau bach o gysur – y gweithlu gofal cymdeithasol, â thâl a heb dâl, yn gwneud popeth o fewn eu gallu i ddod â chysur pan oedd ei angen fwyaf.

Mae'r cofnod hwn yn sicrhau nad yw'r profiadau hyn yn cael eu hanghofio, gan anrhydeddu brwydrau a gwydnwch anhygoel y rhai mewn gofal, eu hanwyliaid a'r rhai a ofalodd amdanynt.

Rydym yn diolch yn fawr iawn i bawb sydd wedi cyfrannu eu profiadau, boed drwy'r ffurflen we, mewn digwyddiadau neu fel rhan o ymchwil wedi'i thargedu. Mae eich myfyrdodau wedi bod yn amhrisiadwy wrth lunio'r cofnod hwn ac rydym yn wirioneddol ddiolchgar am eich cefnogaeth.

Diolchiadau

Hoffai tîm Pob Stori’n Bwysig hefyd fynegi ei werthfawrogiad diffuant i’r holl sefydliadau a restrir isod am ein helpu i gasglu a deall llais a phrofiadau gofal aelodau eu cymunedau. Roedd eich cymorth yn amhrisiadwy i ni gyrraedd cymaint o gymunedau â phosibl. Diolch i chi am drefnu cyfleoedd i dîm Pob Stori’n Bwysig glywed profiadau’r rhai rydych chi’n gweithio gyda nhw naill ai’n bersonol yn eich cymunedau, yn eich cynadleddau, neu ar-lein.

Carers UK

Gofalwyr yr Alban

Gofalwyr Cymru

Gofalwyr Gogledd Iwerddon

Cynghrair Cymdeithas Gofal

Preswylwyr a staff yng nghartrefi nyrsio a gofal Priory

Cymorth i Ofalwyr Caerliwelydd ac Eden

Ymddiriedolaeth Dementia

Ail-ymgysylltu

Cynghrair Darparwyr Gofal

Cymdeithas Gofal Genedlaethol

Ymddiriedolaeth Gofalwyr

Angor

Gofal Cysegr

Hosbis y DU

Rhwydwaith Menywod Mwslimaidd y DU

Cartrefi Methodistaidd (MHA)

Trosolwg

Sut y dadansoddwyd straeon

Mae pob stori a rennir gyda'r Ymchwiliad yn cael ei dadansoddi a bydd yn cyfrannu at un neu fwy o ddogfennau thema fel hon. Cyflwynir y cofnodion hyn o Mae Pob Stori'n Bwysig i'r Ymchwiliad fel tystiolaeth. Mae hyn yn golygu y bydd canfyddiadau ac argymhellion yr Ymchwiliad yn cael eu llywio gan brofiadau'r rhai yr effeithiwyd arnynt gan y pandemig.

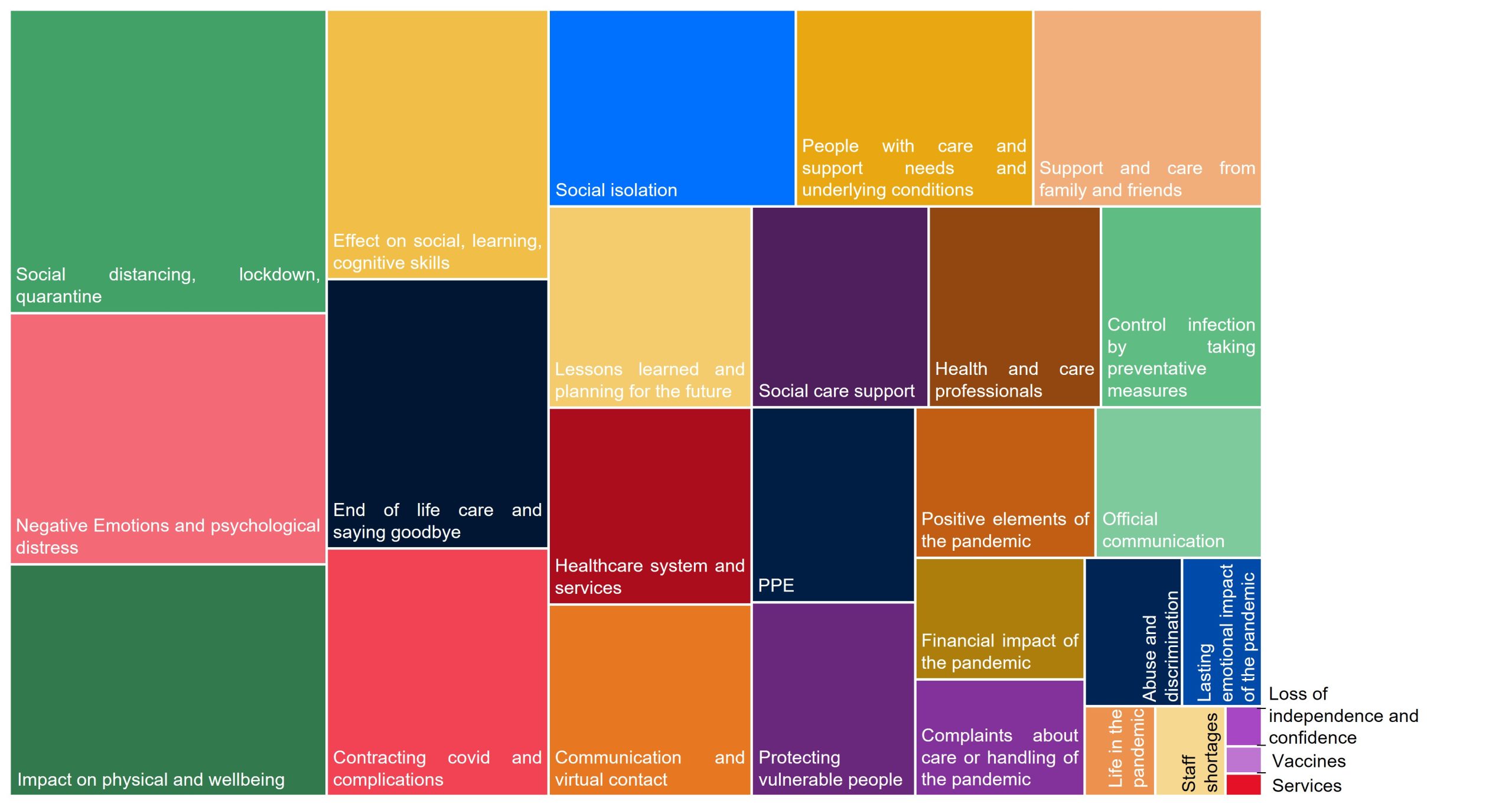

Mae'r straeon a ddisgrifiodd brofiadau gofal cymdeithasol i oedolion yn ystod y pandemig wedi'u dwyn ynghyd a'u dadansoddi i amlygu themâu allweddol. Mae'r dulliau a ddefnyddiwyd i archwilio straeon sy'n berthnasol i'r modiwl hwn yn cynnwys:

- Dadansoddi 46,485 o straeon a gyflwynwyd ar-lein i'r Ymchwiliad, gan ddefnyddio cymysgedd o brosesu iaith naturiol (NLP) ac ymchwilwyr yn adolygu a chatalogio'r hyn y mae pobl wedi'i rannu. (Gweler tudalennau 26 a 27 am esboniad pellach o NLP)

- Ymchwilwyr yn tynnu ynghyd themâu o 336 o gyfweliadau ymchwil gyda'r rhai a oedd yn ymwneud â gofal cymdeithasol i oedolion yn ystod y pandemig. Roedd y rhai a gyfwelwyd yn cynnwys: pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth, eu hanwyliaid, gofalwyr di-dâl a gweithwyr gofal cymdeithasol proffesiynol.

- Ymchwilwyr yn tynnu ynghyd themâu a godwyd gan y cyhoedd a grwpiau cymunedol a gymerodd ran mewn digwyddiadau gwrando Mae Pob Stori yn Bwysig ledled Lloegr, yr Alban, Cymru a Gogledd Iwerddon. Mae rhagor o wybodaeth am y sefydliadau y bu’r Ymchwiliad yn gweithio gyda nhw i drefnu’r digwyddiadau gwrando hyn wedi’i chynnwys yn adran gydnabyddiaeth y cofnod hwn.

Mae rhagor o fanylion am sut y daethpwyd â straeon pobl ynghyd a'u dadansoddi yn y cofnod hwn wedi'u cynnwys yn y Cyflwyniad ac yn yr Atodiad. Mae'r ddogfen yn adlewyrchu gwahanol brofiadau heb geisio eu cymodi, gan ein bod yn cydnabod bod profiad pawb yn unigryw.

Drwy gydol y cofnod, rydym wedi cyfeirio at bobl sy'n rhannu eu straeon gyda Every Story Matters yn y ffyrdd a ddisgrifiwyd uchod fel 'cyfranwyr'. Mae cyfranwyr wedi chwarae rhan bwysig wrth ychwanegu at dystiolaeth yr Ymchwiliad ac at gofnod swyddogol y pandemig. Lle bo'n briodol, rydym hefyd wedi disgrifio mwy amdanynt (er enghraifft, gwahanol fathau o staff sy'n gweithio ym maes gofal cymdeithasol) neu'r rheswm pam y gwnaethon nhw rannu eu stori (er enghraifft, fel person ag anghenion gofal a chymorth neu fel gofalwr di-dâl). Mae'r tabl isod yn amlinellu'r gwahanol ymadroddion ac iaith a ddefnyddiwn drwy gydol y cofnod i ddisgrifio grwpiau allweddol.

| Ymadrodd | Diffiniad |

|---|---|

| Gweithiwr gofal cymdeithasol proffesiynol | Mae hwn yn derm cyffredinol ar gyfer y rhai sy'n gweithio ym maes gofal cymdeithasol, gan gynnwys gweithwyr gofal, rheolwyr cofrestredig (cartrefi gofal a darparwyr gofal cartref) a gweithwyr gofal cymdeithasol proffesiynol eraill, fel gweithwyr cymdeithasol. |

| Gweithwyr gofal | Mae hyn yn cynnwys y rhai sy'n gweithio mewn cartref gofal preswyl a gweithwyr gofal cartref sy'n darparu gofal a chymorth â thâl yng nghartref person ei hun. |

| Gofalwr di-dâl | Defnyddir y term hwn i ddisgrifio aelodau o'r teulu a ffrindiau sy'n darparu gofal a chymorth mewn rhinwedd bersonol yn hytrach na phroffesiynol, heb dderbyn iawndal ariannol. |

| Person ag anghenion gofal a chymorth | Rhywun sydd angen cymorth gyda bywyd bob dydd, a allai gynnwys cymorth gan ofalwyr di-dâl neu weithwyr gofal cartref gartref neu gan staff mewn cartref gofal. |

Y straeon a rannwyd gan bobl am ofal cymdeithasol yn ystod y pandemig

Cafodd y pandemig effaith ddinistriol ar y rhai ag anghenion gofal, eu teuluoedd a gofalwyr di-dâl a gweithwyr gofal cymdeithasol proffesiynol.

Disgrifiodd y rhai a oedd ag anwylyd ag anghenion gofal a chymorth a fu farw yn ystod y pandemig y trawma gwaethygol o beidio â gallu bod gyda'u hanwyliaid cyn a phan fyddant yn marw a pheidio â gallu galaru'n iawn drostynt. Disgrifiodd gweithwyr gofal cymdeithasol yr ofid o gefnogi pobl ar ddiwedd eu hoes a sefyll i mewn yn effeithiol dros deuluoedd y rhai sy'n marw.

Roedd unigrwydd, pryder, gofid a hwyliau isel yn gyffredin. Arweiniodd cyfyngiadau symud a chyfyngiadau ymweld at fwy o unigedd a gofid i bobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth. Rhoddodd hyn bwysau enfawr ar anwyliaid, gofalwyr di-dâl a gweithwyr gofal cymdeithasol proffesiynol a chymerodd ei doll ar eu hiechyd meddwl a'u lles.

Cynyddodd y pwysau hwnnw ymhellach pan gafodd pobl eu rhyddhau o ysbytai i gartrefi gofal â staff cynyddol brin heb brofion Covid-19 neu gyda chanlyniadau profion anghywir neu hen ffasiwn.

Fodd bynnag, clywsom hefyd straeon cadarnhaol am sut y daeth cymunedau, ffrindiau a theulu at ei gilydd i gefnogi'r rhai mewn angen, gyda pherthnasoedd yn aml yn cryfhau o ganlyniad. Teimlai rhai cyfranwyr eu bod wedi'u hamddiffyn rhag y pandemig a chydnabu'r gofal rhagorol a gawsant mewn sefyllfaoedd heriol.

Effaith y pandemig ar ofal cymdeithasol

Cloeon a chyfyngiadau ar leoliadau gofal

Roedd llawer o bobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth, eu hanwyliaid a gweithwyr gofal cymdeithasol proffesiynol yn teimlo bod y cyfyngiadau symud a'r mesurau cadw pellter cymdeithasol yn straen ac yn llethol. I bobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth oedd yn byw gartref, roedd y cyfyngiadau symud yn arwain at deimladau o unigrwydd ac arwahanrwydd. Yn aml, roedd cyfyngiadau symud a chyfyngiadau yn golygu nad oeddent yn gallu cael mynediad at y gofal a'r cymorth oedd eu hangen arnynt, boed hyn gan anwyliaid neu weithwyr gofal cymdeithasol proffesiynol.

| “ | Doeddwn i a fy ngofalwr di-dâl ddim yn gallu gweld pobl eraill … Dw i'n meddwl bod fy mhoen a phethau fel hyn wedi gwaethygu, fel poen yn fy nghymalau, oherwydd fy mod i'n symud o gwmpas llai… Doeddwn i ddim yn gallu mynd i'm apwyntiadau ffisiotherapi chwaith ac nid oedd mynediad at apwyntiadau ar-lein. Felly, roedd hynny wedi dod i ben yn llwyr…roedd hynny'n ddrwg iawn.”

- Person ag anghenion gofal a chymorth, Lloegr |

Roedd teulu a ffrindiau’n teimlo pwysau ychwanegol i ddarparu gofal di-dâl oherwydd cyfyngiadau’r cyfnod clo. Roedden nhw’n ei chael hi’n anodd gwybod sut i ddarparu’r gofal cywir neu sut i gael mynediad at wasanaethau gofal a chymorth. Roedd eu cyfrifoldebau gofalu’n aml yn cynyddu, ac roedd hyn yn arwain at straen a phryder gyda llawer yn ansicr sut i ymdopi.

| “ | Roedd gan fy mam-gu ddementia, felly cyn i ni i gyd fod yn gofalu amdani…ond wedyn doedd neb yn cael ymweld â'i gilydd…dechreuodd hi fynd yn rhyfedd a dim ond fi a hi oedd yna…Roeddwn i'n arfer ei helpu i fwyta, ei brecwast, ei chinio, ceisio rhoi bath iddi, cael hi i sefyll i fyny a hyd yn oed fel yn yr ardd, ceisio gwneud iddi gerdded ychydig…weithiau, roedd yn mynd yn ormod, roedd yn mynd yn ormod [i fy iechyd meddwl].”

– Gofalwr di-dâl, Lloegr |

| “ | Penderfynon ni na allem adael i [fy nhad] fynd i'r ysbyty. Felly, fe wnaethon ni, fy chwaer a minnau, wneud gofal personol…y glanhawr oedd gan fy rhieni, roedd hi hefyd wedi bod yn ofalwr, a dysgodd hi i ni sut i wneud hynny.”

– Gofalwr di-dâl, Lloegr |

| “ | Yn sydyn, yn ystod Covid, doedd dim amser i ddianc i amgylchedd lle gallech chi fod yn chi'ch hun neu gyda phobl eraill sydd â phrofiadau tebyg, neu efallai dim ond cymryd amser i ffwrdd. Felly, roeddech chi'n gofalu am bobl yn gyson 24 awr a llai amdanoch chi'ch hun. Felly, roedd yn bryder ac yn anobaith eithafol.

– Gofalwr di-dâl, Lloegr |

Roedd cyfyngiadau ymweld hefyd yn anodd i deuluoedd a ffrindiau. Roeddent am sicrhau bod pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth yn ddiogel ac yn cael gofal priodol. Dywedodd cyfranwyr wrthym sut roeddent yn gwerthfawrogi ymweliadau ffenestr, galwadau ffôn a fideo ac, yn ddiweddarach yn y pandemig, ymweliadau â phellter cymdeithasol. Fodd bynnag, nid oedd hyn yn gwneud iawn am y diffyg cyswllt personol agos, yn enwedig gallu cyffwrdd yn gorfforol, cysuro a chofleidio'r rhai yr oeddent yn gofalu amdanynt.

| “ | Felly, ar un pen [o'r bwrdd] roedd fy mam, yn ei chôt yn ei chadair olwyn, ac roeddwn i ar y pen arall, rhyw fath, 6 neu 8 troedfedd i ffwrdd ac roedd yn ymweliadau 'carchar'…Rwy'n bloeddio arni o ben arall bwrdd hir…o flaen gofalwyr sydd fel gwarchodwyr ac roeddech chi eisiau dweud, 'Rwyf eisiau rhywfaint o breifatrwydd.' Doedd hi ddim yn gallu deall pam ar y ddaear nad oeddwn i'n eistedd gyda hi. Roedd yn eithaf gofidus mewn gwirionedd, ein bod ni'n cael ein trin fel 'na, roedd yn arfer fy ngwneud yn ddig iawn.”

– Anwylyd preswylydd cartref gofal, Lloegr |

Dywedodd rhai gweithwyr gofal cymdeithasol proffesiynol fod y gallu i barhau i weithio yn ystod y cyfnod clo wedi rhoi ymdeimlad o normalrwydd iddynt. Roedd llawer o rai eraill yn teimlo'n ynysig ac wedi'u llethu. Roedd rhaid i staff weithio dan bwysau difrifol i reoli gofynion cystadleuol darparu gofal, gyda llwyth gwaith uwch a llai o gefnogaeth dros fisoedd lawer. Symudodd rhai staff cartrefi gofal i'w gweithleoedd i amddiffyn preswylwyr a'u teuluoedd eu hunain. Treuliasant gyfnodau hir i ffwrdd oddi wrth anwyliaid. Arweiniodd hyn at deimladau o unigrwydd, blinder a gofid. Roedd y cyfyngiadau ar ymweliadau â chartrefi gofal hefyd yn rhoi pwysau a chyfrifoldeb ychwanegol ar staff, a oedd weithiau'n gorfod cymryd lle'r teulu wrth ofalu am breswylwyr.

| “ | Daethom yn fwy na dim ond gofalwyr y preswylwyr; tyfodd ein perthynas â nhw yn ystod y cyfnod hwnnw, daethom yn deulu iddyn nhw pan nad oedd eu plant eu hunain yn cael ymweld mwyach. Roedden ni'n eu caru nhw, fel ein rhai ni. Ni oedd yr unig bobl roedden nhw'n eu gweld bob dydd a daeth yn norm iddyn nhw.”

– Gweithiwr cartref gofal, Gogledd Iwerddon |

Cafodd pobl sy'n derbyn gofal cartref ymweliadau byrrach a llai aml wrth i wasanaethau gofal gael eu tarfu gan gyfnodau clo a phellhau cymdeithasol. Dywedodd gweithwyr gofal fod hyn yn lleihau cysondeb ac ansawdd y gofal y gallent ei ddarparu. Roedd staff hefyd yn ei chael hi'n anodd cefnogi pobl ag anghenion gofal cynyddol. Yn aml, gweithwyr gofal oedd yr unig bobl yr oeddent mewn cysylltiad â nhw yn ystod y cyfnodau clo.

| “ | Dim oedi, dim sgwrsio, dim gormod ar ôl i'r gofal hanfodol gael ei ddarparu; dim ond symud ymlaen i'r un nesaf oedd hi. Ie, roedd yn eithaf cyfyngedig…lle byddwn i fel arfer yn treulio awr a chwarter gydag un fenyw, efallai fy mod i wedi bod yno am 45 munud yn unig, felly ie, roedd yn anodd… roedd yn eithaf creulon ar y bobl agored i niwed roeddwn i'n darparu gofal iddyn nhw.”

– Gweithiwr gofal cartref, Cymru |

Roedd llawer o bobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth yn cael trafferth ymdopi ag effaith llai o gyswllt cymdeithasol ac unigedd cynyddol. Roedd rhai yn datgysylltu'n emosiynol oddi wrth deulu a ffrindiau, tra bod eraill yn rhoi'r gorau i fwyta digon gan eu bod yn teimlo'n bryderus ac yn isel eu hysbryd.

| “ | Doedd hi ddim yn gallu deall pam mai dim ond drwy’r ffenestr y gallai fy ngweld…roedd hi’n rhoi’r gorau i fwyta oherwydd ei bod hi’n teimlo’n isel ei hysbryd gan fywyd heb ymwelwyr, ac ymweliadau gofal byr iawn gan y staff.”

– Aelod o deulu galarus preswylydd cartref gofal, yr Alban |

Clywsom hefyd sut y dechreuodd pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth ymddwyn mewn ffyrdd yr oedd gweithwyr proffesiynol teulu a gofal cymdeithasol yn eu cael yn heriol. Effeithiodd hyn yn arbennig ar bobl â dementia neu anabledd dysgu a phobl awtistig.

| “ | Roeddwn i'n gweithio mewn [cartref gofal]. Gwelais oedolion ag anableddau dysgu heb ddeall yn llawn pam roedd eu bywydau beunyddiol wedi newid, a oedd yn golygu bod staff wedi gweld ac wedi profi mwy a mwy o achosion o ymddygiad heriol ... cynyddodd ymosodiadau staff.”

– Gweithiwr cartref gofal, yr Alban |

| “ | Rwy'n gweithio mewn cartref gofal sy'n cefnogi oedolion ag anableddau dysgu. Cymerodd yr effaith ar y preswylwyr o gael eu hamddifadu o ymweliadau priodol gan eu teulu sawl ffurf: ymddygiad heriol, mynd yn encilgar… daeth preswylwyr a oedd fel arfer yn gymwynasgar iawn yn ddiog ac yn hwyliau mawr, daeth eu cyswllt â theuluoedd [ar y ffôn neu drwy alwad fideo] yn sbardunau [ar gyfer ymddygiad heriol].”

– Gweithiwr cartref gofal, yr Alban |

Roedd pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth hefyd yn ei chael hi'n anodd dychwelyd i'w gweithgareddau blaenorol a'u lefel o annibyniaeth ar ôl i'r cyfyngiadau gael eu llacio. Rhannodd llawer sut y gwnaethon nhw golli hyder ac maen nhw wedi parhau i fod yn encilgar.

| “ | Mae [y pandemig] wedi fy ngadael heb hyder… Doeddwn i ddim yn gallu, rhyw fath, cymysgu ac allwn i ddim mynd allan yn chwerthin a mwynhau fy hun. Roedd yn ddrwg iawn. Wyddoch chi, roeddwn i'n teimlo [fel] carcharor. Roeddwn i'n ei gasáu. Dioddefodd fy iechyd corfforol yn fawr oherwydd nad oeddwn i'n gwneud dim… a dydw i ddim wedi gallu ei gael yn ôl. Rwy'n ofalus ac yn bryderus iawn nawr.”

– Person ag anghenion gofal a chymorth, Cymru |

Rhyddhau o ysbytai i gartrefi gofal

Clywsom sut roedd cartrefi gofal yn aml yn derbyn preswylwyr newydd neu breswylwyr presennol yn cael eu rhyddhau o ysbytai heb rybudd digonol, gyda gwybodaeth gyfyngedig am eu cyflwr neu heb unrhyw brofion Covid-19 cywir neu ddiweddar. Creodd hyn heriau sylweddol i gartrefi gofal. Rhoddodd straen ar staff oherwydd y llwyth gwaith ychwanegol a'r ansicrwydd a theimlwyd ei fod yn cynyddu'r risg o Covid-19 yn lledaenu.

| “ | Dechreuon ni gael preswylwyr pan fydden nhw'n mynd i'r ysbyty, roedden nhw'n cael eu hanfon yn ôl i'r cartref gofal yn gyflym heb gynllun rhyddhau cadarn mewn gwirionedd. Ac yna digwyddodd bod pobl oedd yn cael eu hanfon yn ôl o'r ysbyty yn dod yn ôl gyda Covid ac yna, yn amlwg, byddai'n dechrau lledaenu. Ar y pryd, doedd dim canllaw o gwbl gan y llywodraeth, ddim yn swyddogol i ni a ddim hyd yn oed ar y teledu lle clywsom y rhan fwyaf o'r canllawiau. Doedd dim byd yna.”

– Nyrs yn gweithio mewn cartref gofal, Lloegr |

Rhannodd rhai cyfranwyr sut roeddent yn teimlo dan bwysau gan dimau rhyddhau ysbytai i dderbyn preswylwyr newydd o ysbytai er nad oedd ganddynt y wybodaeth na'r arbenigedd i ofalu amdanynt. Cododd hyn bryderon ynghylch diogelwch cleifion ac addasrwydd y gofal y gallent ei ddarparu.

| “ | Gofynnwyd i gartrefi gofal gymryd cleifion Covid o'r ysbyty i leihau'r pwysau ar wasanaethau acíwt. Yn lle hynny, gwrthodom, yn ystod y don gyntaf, gymryd preswylwyr newydd, er ein bod wedi ein rhoi dan bwysau i wneud hynny, gan gael gwybod mai 'ein dyletswydd foesol' oedd hi.”

– Rheolwr cofrestredig cartref gofal, Lloegr |

| “ | Ar y dechrau [rhyddhawyd pobl i gartrefi gofal] heb unrhyw brofion ar waith ac ar adegau hefyd heb unrhyw asesiad go iawn i benderfynu ar farn a dymuniadau'r bobl hŷn dan sylw. Roeddwn i'n teimlo bod hyn yn gyfaddawd enfawr ar fy ngwerthoedd moesegol. Roedd yn amlwg bod ysbytai'n cael eu llethu.”

– Gweithiwr cymdeithasol, yr Alban |

Fe greodd dyfodiad preswylwyr a brofodd yn bositif am Covid-19 yn fuan ar ôl eu rhyddhau ymdeimlad o gyfrifoldeb dros atal achosion ac amddiffyn preswylwyr a staff eraill. Rhannodd anwyliaid a gofalwyr di-dâl hefyd sut yr oeddent yn teimlo ymdeimlad o ofn a phanig pan glywsant am bobl a gafodd eu rhyddhau o'r ysbyty i'r cartref gofal yn profi'n bositif am Covid-19.

| “ | Dau berson a gafodd eu rhyddhau [o'r ysbyty yn ôl i'r cartref gofal, ar ôl profi] yn negatif. Ddeuddydd yn ddiweddarach, daeth i'r amlwg eu bod nhw'n dioddef o Covid. [Wrth glywed ei fod yn y cartref] roedd fel pe bai fy ofnau gwaethaf wedi dod i'r amlwg. Daliais i aros am yr alwad i ddweud bod ganddi Covid. Doeddwn i ddim yn gallu cysgu, doeddwn i ddim yn gallu bwyta - roedd yn artaith.”

– Anwylyd preswylydd cartref gofal, yr Alban |

Gofal diwedd oes a phrofedigaeth

Gwnaeth cyfyngiadau ymweld a mesurau rheoli heintiau Covid-19 eraill hi'n anodd iawn i anwyliaid ffarwelio â theulu neu ffrindiau ar ddiwedd eu hoes. Clywsom sut y bu farw pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth heb weld eu hanwyliaid oherwydd cyfyngiadau ymweld a oedd ar waith yn ystod y cyfnod clo cyntaf. Achosodd hyn alar a gofid aruthrol i aelodau'r teulu.

| “ | Wyddoch chi [pan oedd fy mam yn marw] byddwn i'n cael galwadau i ddweud bod hyn wedi digwydd neu hynny. Mae'n peri gofid. Mae'n dod â'r teimlad hwnnw o straen, am wn i, ond hefyd galar. Ac, am wn i, teimlad o unigedd, mewn gwirionedd, ynglŷn â... methu bod yno'n gorfforol na gwneud rhywbeth amdano. Diymadferthedd, dyna fyddai'r gair mewn gwirionedd. Diymadferthedd.”

– Aelod o’r teulu sydd wedi colli rhywun, Lloegr |

| “ | Doedden ni ddim yn gallu ei weld – wnaethon nhw byth ei weld eto. A phan fu farw, wrth gwrs, doedden ni ddim yn gallu mynd i angladd, doedden ni ddim yn gallu gwneud dim byd o gwbl. A dydw i ddim yn meddwl fy mod i erioed wedi teimlo mor annigonol.”

– Aelod o’r teulu sydd wedi colli rhywun, digwyddiad gwrando ar-lein |

Roedd pobl ar ddiwedd eu hoes a oedd yn cael gofal gartref gan ofalwyr di-dâl neu staff gofal cartref yn ei chael hi'n anodd cael gofal diwedd oes. Clywsom sut roedd yn rhaid i aelodau'r teulu ofalu amdanynt heb unrhyw gefnogaeth neu gymorth o bell yn unig gan weithwyr gofal iechyd a chymdeithasol proffesiynol. Roedd hyn yn rhoi cyfrifoldeb mawr ar anwyliaid.

| “ | Roedd [fy ngŵr] eisiau mynd i [gartref nyrsio] ac ni allent ei gymryd. [Felly fe wnaethon ni ofalu amdano gartref], nyrs neu feddyg gofal diwedd oes, dydw i ddim yn siŵr, yn ei ffonio bob pump neu chwe wythnos…y cyfan a wnaethon nhw, gyda phob problem fach oedd ganddo, bydden nhw'n archebu llwyth o gyffuriau. Doedden ni ddim yn hapus am hynny. Roeddwn i'n teimlo y gallai rhywun fod wedi dod i ymweld ag ef o ofal diwedd oes [a'n helpu ni].”

– Aelod o’r teulu sydd wedi colli rhywun, Lloegr |

Yn aml, roedd gweithwyr gofal yn cefnogi ac yn cysuro pobl wrth iddynt farw, gan nad oedd eu teulu a'u ffrindiau'n gallu ymweld. Rhannasant sut roeddent yn teimlo'n llethol ac yn cael y profiad yn heriol iawn. Dywedodd llawer wrthym sut roedd amlder marwolaethau, presenoldeb Offer Diogelu Personol (PPE) a'r cyfyngiadau ar ymweliadau teuluol yn gwneud i ofal diwedd oes deimlo'n amhersonol. Darparodd gweithwyr gofal ofal tosturiol pan oeddent eisoes dan bwysau difrifol a rhoddodd hyn doll emosiynol enfawr arnynt.

| “ | Roedd staff yn eistedd ar alwadau fideo gyda theuluoedd, yn ffarwelio â'u hanwyliaid am y tro olaf. Roedd hynny'n erchyll. Wyddoch chi, roedd staff yn crio gyda'r preswylwyr, oherwydd roedd mor emosiynol iddyn nhw. Roedden nhw'n dal eu dwylo nes iddyn nhw farw.”

– Gweithiwr cartref gofal, Gogledd Iwerddon |

| “ | Fe wnaethon ni wir geisio darparu'r gofal mwyaf tosturiol posibl… fe wnaethon ni barhau i ddarparu'r gofal proffesiynol oedd ei angen ac roedd yn fath cariadus o ofal…er gwaethaf yr holl heriau.”

– Gweithiwr cartref gofal, Lloegr |

Clywsom sut roedd rhai cartrefi gofal yn caniatáu i deulu a ffrindiau ymweld â'u hanwyliaid oedd yn marw hyd yn oed pan oedd cyfyngiadau ar waith. Roedd hyn yn cael ei werthfawrogi'n fawr gan anwyliaid ac roedd llawer yn cydnabod bod gweithwyr gofal yn gwneud eu gorau mewn sefyllfa anodd.

| “ | Byddaf yn ddiolchgar am byth i'r cartref gofal am ganiatáu inni gael yr amser byr hwnnw gyda [fy mam] ar ddiwedd ei hoes.”

– Aelod o’r teulu sydd wedi colli rhywun, Cymru |

Fodd bynnag, gadawyd llawer o anwyliaid ag atgofion poenus o frwydr a dioddefaint. Roeddent wedi’u difrodi’n llwyr na allent wneud mwy i helpu a chefnogi’r person yr oeddent yn gofalu amdano ar ddiwedd eu hoes.

| “ | Roedd fy mam mewn trallod mawr, mewn cyflwr ofnadwy, ac ni allent gael y mwgwd CPAP arni, felly es i mewn gyda PPE llawn ymlaen, gallwn ei chlywed yn sgrechian yn gofyn i'w mam ddod i'w chymryd i ffwrdd. Roedd hi'n gwthio ac yn ymladd, nid oedd hi'n wan. Ni allai glywed fy llais na gweld fy wyneb, roeddwn i eisiau eistedd a'i dal, ond ni chaniatawyd i mi. Ni allwn ei helpu, felly dywedwyd wrthyf fod yn rhaid i mi adael.”

– Aelod o’r teulu sydd wedi colli rhywun, digwyddiad gwrando, Gogledd Iwerddon |

Ar ôl y farwolaeth, effeithiodd cyfyngiadau ar baratoadau ar gyfer yr angladd a phwy allai fynychu. I bobl o grwpiau crefyddol a'r rhai o gefndiroedd lleiafrifoedd ethnig, effeithiodd hyn ar arferion ynghylch marwolaeth, megis paratoi'r corff a galaru am eu colled fel cymuned.

Cododd rhai anwyliaid a gweithwyr gofal cymdeithasol bryderon ynghylch y driniaeth a'r gofal a ddarperir i bobl ar ddiwedd oes. Rhannasant brofiadau o benderfyniadau triniaeth yn cael eu gwneud heb drafodaethau nac ymgynghori.

| “ | Am y pedair i bum wythnos [yn yr hosbis]…dywedwyd wrtha’i y byddai’n marw bob dydd. Tynnwyd y tiwb a’r IV allan a dydw i ddim yn gwybod pam eto. Yn y gwres ofnadwy, byddent yn cynnig dŵr oer iddo ac ni fyddent yn dod yn ôl. Ni allai fwyta na yfed, dim ond ei adael yn ei ystafell. Roedd yn ofnadwy.”

– Aelod o’r teulu sydd wedi colli rhywun, digwyddiad gwrando, Cymru |

| “ | Dywedais i roi hylifau iddo [pan wnaethon nhw ffonio i ddweud nad oedd e’n yfed llawer, sy’n gyffredin gyda dementia], ond roedden nhw wedi cael gwybod i beidio â rhoi hylifau iddo. Fe wnaethon nhw ei dynnu oddi ar ei feddyginiaeth teneuo gwaed – un o’r pethau allweddol a fe wnaethon nhw ei dynnu oddi ar y gwrthgeulydd, oddi ar ei glwt morffin a rhoi rhywbeth iddo ar gyfer cynhyrfu, dwi’n gwybod bod fy nhad yn gynhyrfus oherwydd ei fod yn ofnus, wedi’i adael gen i, roedd e wedi arfer â fi yno drwy’r amser.”

– Aelod o’r teulu sydd wedi colli rhywun, digwyddiad gwrando, Gogledd Iwerddon |

Roedd pryderon penodol ynghylch hysbysiadau Peidiwch â Cheisio Adfywio Cardiopwlmonaidd (DNACPR). Dywedodd rhai cyfranwyr wrthym am yr hyn yr oeddent yn credu oedd hysbysiadau DNACPR cyffredinol a osodwyd ar bobl oherwydd bod y person yn byw mewn cartref gofal neu ag anabledd dysgu. Achosodd y diffyg tryloywder a chyfranogiad yn y penderfyniadau hyn ofid ac ansicrwydd i deuluoedd.

| “ | Rhoddodd ein meddyg lleol waharddiad DNACPR cyffredinol ar ei holl gleifion i’w hatal rhag cymryd gwelyau yn yr ysbyty, rhywbeth a heriodd teuluoedd.”

– Gweithiwr cartref gofal, Cymru |

| “ | Gofynnodd y meddyg teulu am gael prawf DNACPR, roedd fy nhad yn gwybod am hyn a'r canlyniadau posibl, roedd eisiau byw, doedd e ddim eisiau un. Yna, darganfyddais fod y meddyg teulu wedi ymweld eto heb rybudd gyda chais DNACPR ac ni wnaethon nhw erioed sôn amdano wrtha i.”

– Aelod o’r teulu sydd wedi colli rhywun, digwyddiad gwrando, yr Alban |

| “ | Mae gen i anabledd…Rwy'n dal i gael fy ysgwyd i graidd fy modolaeth, eu bod nhw wedi gorfodi hysbysiadau 'Peidiwch ag Adfywio' ar y rhai ohonom sydd ag anabledd sylweddol neu dros oedran penodol.”

– Person ag anghenion gofal a chymorth, Cymru |

Dywedodd pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth a'r rhai oedd yn agored i niwed yn glinigol wrthym hefyd pa mor frawychus oedd sgyrsiau ynghylch diwedd oes a DNACPR.

| “ | Yn fuan ar ôl derbyn fy llythyr amddiffyn, cefais alwad ffôn gan fy meddygfa, a rhoddodd y galwad ffôn hon yr ofn mwyaf ynof hyd yma. Yn ystod y sgwrs gofynnwyd i mi a oeddwn wedi trafod fy nymuniadau diwedd oes gyda fy anwyliaid. Fel a oeddwn eisiau mynd i'r ysbyty neu aros gartref, a oeddwn wedi cael DNACPR. Gwnaeth hyn fy nychryn.”

– Person ag anghenion gofal a chymorth, yr Alban |

PPE a mesurau rheoli heintiau Covid-19

Roedd gweithwyr gofal cymdeithasol proffesiynol yn ddryslyd, dan straen ac yn ansicr ynghylch canllawiau sy'n newid yn aml ar Offer Diogelu Personol (PPE). Roedd yn rhaid i ddarparwyr gofal ailddefnyddio eitemau sengl, dogni cyflenwadau neu gaffael PPE o ysbytai, elusennau a sefydliadau neu fusnesau cymunedol eraill gan fod prinder PPE yn ystod camau cynnar y pandemig. Roedd darparwyr gofal yn bryderus ynghylch ansawdd ac addasrwydd PPE hyd yn oed wrth i'r pandemig fynd rhagddo a'r cyflenwad o PPE wella.

| “ | Y masgiau, ar un adeg pryd bynnag y byddech chi'n ceisio eu rhoi ymlaen, bydden nhw'n torri. Roedd y rheolwyr yn newid rhai gwahanol nes i ni gael yr un cywir.”

– Gweithiwr cartref gofal, Lloegr |

Roedd gweithwyr gofal cymdeithasol proffesiynol yn wynebu llwythi gwaith ac anghysur cynyddol wrth iddynt wisgo a thynnu PPE i ffwrdd yn gyson. Roedd protocolau glanhau a diheintio mwy trylwyr yn dwysáu'r pwysau ar y gweithlu ymhellach.

| “ | Byddem yn darganfod bod yn rhaid i ni wneud llawer mwy o waith oherwydd bod pobl yn ynysu…ni oedd yr unig bobl oedd yn mynd i mewn i weld pobl. Roeddem yn gweithio 16 awr y dydd… roedd [y PPE] yn cymryd llawer o amser ac yn sicr yn cymryd amser i ffwrdd o ochr gofal personol pethau.”

– Gweithiwr gofal cartref, Lloegr |

Roedd llawer o staff gofal cartref hefyd yn gweithio ar eu pennau eu hunain, gan ychwanegu at eu hynysu. Nid oeddent yn gallu cael cymorth gan gydweithwyr a rheolwyr eraill ynghylch PPE a heriau wrth ddarparu gofal.

Yn aml, byddai pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth, anwyliaid a gofalwyr di-dâl yn cael eu tawelu gan PPE. Fodd bynnag, roedd hefyd yn creu rhwystrau cyfathrebu. Roedd rhai pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth a gweithwyr gofal cymdeithasol proffesiynol yn ei chael hi'n anodd meithrin perthnasoedd. Roedd masgiau'n cuddio mynegiadau wyneb ac emosiynau, gan ei gwneud hi'n arbennig o anodd deall ciwiau di-eiriau.

| “ | Dim ond llygaid rhywun oeddech chi'n gallu eu gweld ac roeddwn i'n teimlo bod pobl yn llai agored pan nad oedden nhw'n gallu gweld eich wyneb. Roedd yn rhaid i chi geisio ymgysylltu â nhw'n fwy. Roedd hi'n anoddach ymgysylltu â phobl pan mae eich wyneb wedi'i orchuddio. Mae pobl yn fwy agored i chi pan allan nhw weld eich wyneb a dydych chi ddim yn hollol yn yr iwnifform honno.”

– Gweithiwr gofal iechyd, Lloegr |

I bobl oedd yn gofalu am unigolion oedd yn fyddar neu'n drwm eu clyw, roedd yr anallu i ddarllen gwefusau yn her sylweddol ac weithiau roedd yn rhaid i staff dynnu eu masgiau, gan gynyddu'r risg o drosglwyddo o bosibl. Clywsom hefyd sut roedd rhai pobl â dementia, unigolion ag anabledd dysgu a phobl awtistig hefyd yn cael PPE yn frawychus ac yn fygythiol. Mewn rhai achosion, arweiniodd hyn at ymddygiad heriol ac yn ei gwneud hi'n anoddach i ofalwyr di-dâl a gweithwyr gofal cymdeithasol proffesiynol ddarparu gofal.

Roedd cyfranwyr yn pryderu am y risgiau o ddal Covid-19 eu hunain neu ei drosglwyddo i aelodau o'r teulu, er gwaethaf y defnydd o PPE. Roedd aelodau o'r teulu a gweithwyr gofal cymdeithasol proffesiynol a oedd yn agored i niwed yn glinigol a phobl o gefndiroedd ethnig lleiafrifol yn arbennig o bryderus ynghylch dal Covid-19.

Prinder staff a sut y darparwyd gofal

Dywedodd cyfranwyr wrthym hefyd sut yr effeithiwyd ar y sector gofal cymdeithasol gan brinder staff difrifol drwy gydol y pandemig. I ddechrau, y rhesymau pam y gadawodd staff y gweithlu oedd yn bennaf oherwydd ofnau o haint, cyflyrau iechyd a oedd yn bodoli eisoes neu broblemau gofal plant yn gysylltiedig â chau ysgolion. Gostyngwyd argaeledd y gweithlu drwy gydol y pandemig ymhellach gan ofynion ynysu ar gyfer achosion positif o Covid-19.

| “ | Staff, gadawodd llawer o bobl oherwydd nad oedden nhw eisiau cael eu rhoi mewn perygl, a oedd wedyn yn golygu bod gennych chi fwy o rotas i'w gorchuddio, mwy o gwsmeriaid i'w gweld a llai o staff i'w defnyddio. Doedd y bobl ddim yn gallu gwisgo PPE, felly bydden nhw'n gadael, felly, unwaith eto, byddai gennych chi fwy o bethau i'w gorchuddio.”

– Gweithiwr gofal cartref, Lloegr |

O fis Tachwedd 2021 tan fis Mawrth 2022 roedd yn ofynnol i staff gofal yn Lloegr gael brechlyn Covid-19 er mwyn parhau i weithio, tra bod cyfranwyr yn yr Alban, Cymru a Gogledd Iwerddon wedi rhannu sut roedd disgwyliad cynyddol y byddent yn cael y brechlyn. Gadawodd rhai staff y gweithlu oherwydd bod cael y brechlyn yn erbyn eu credoau personol, tra bod gan eraill bryderon am sgîl-effeithiau posibl. Roedd y pryderon hyn yn effeithio'n arbennig ar bobl o gefndiroedd lleiafrifoedd ethnig. Clywsom hefyd sut roedd rhai pobl a oedd yn gweithio ar fisa iechyd a gofal, yr oedd eu preswylfa yn y DU yn dibynnu ar eu cyflogaeth, yn teimlo dan bwysau ychwanegol i gael y brechlyn gan eu bod yn poeni am effeithiau colli eu swydd.

| “ | Roedd gennym ni broblem; doedd cwpl o staff ddim eisiau cael brechlyn. Felly, dywedwyd wrthyn nhw fwy neu lai, 'Wel os nad ydych chi wedi cael eich brechlyn yna allwch chi ddim gweithio,' felly achosodd hynny gynhyrfusrwydd a dadleuon eraill.”

– Rheolwr cofrestredig cartref gofal, Lloegr |

Weithiau, roedd prinder staff yn arwain at berthnasoedd straen rhwng cydweithwyr wrth iddynt weithio o dan bwysau cynyddol ar sifftiau hirach gyda llwyth gwaith hyd yn oed yn fwy. Roedd prinder staff hefyd yn gadael darparwyr gofal yn ei chael hi'n anodd dod o hyd i adnoddau ar gyfer gwasanaethau ac i ofalu am bobl. Yn aml, roedd darparwyr gofal yn dibynnu ar staff asiantaeth i lenwi'r bylchau hyn. Yn aml, gweithwyr gofal dros dro oedd staff asiantaeth a oedd yn newid yn aml ac nad oeddent bob amser yn adnabod y bobl yr oeddent yn gofalu amdanynt, a oedd yn effeithio ar ansawdd y gofal a ddarparwyd.

| “ | Byddech chi'n cael staff asiantaeth. Maen nhw'n dda, ond dydyn nhw ddim yn rheolaidd. Dydyn nhw ddim yn adnabod y preswylwyr hyn cymaint. Ac maen nhw'n dod i mewn gyda'r ofn hwnnw, 'O, mae Covid yn y cartref hwn,' a dim ond y gofal sylfaenol [lefel y gofal] y byddan nhw'n ei wneud. Roedd y sefyllfa gyfan yn drychineb. Yn y rhan fwyaf o achosion, ni chafodd preswylwyr y gofal y dylen nhw ei gael.”

– Nyrs yn gweithio mewn cartref gofal, Lloegr |

Mynediad at wasanaethau gofal iechyd a phrofiad ohonynt

Clywsom sut y cafodd mynediad at wasanaethau gofal iechyd fel meddygon teulu, gwasanaethau cymunedol ac ysbytai ei leihau neu ei ohirio'n sylweddol yn ystod y pandemig. Dywedodd pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth wrthym sut y symudodd apwyntiadau i ymgynghoriadau ar-lein neu dros y ffôn, nad oeddent bob amser yn addas, yn enwedig i'r rhai ag anghenion cyfathrebu ychwanegol, pobl ag anabledd dysgu a'r rhai â dementia. Roedd mynediad at ofal iechyd brys hefyd yn heriol oherwydd pwysau cynyddol ar ysbytai ac ofnau o ddal Covid-19.

Disgrifiodd rhai gweithwyr gofal cymdeithasol proffesiynol enghreifftiau o rai gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol yn petrusgar neu'n methu ymweld â phobl yn bersonol oherwydd prinder staff. Arweiniodd hyn at lwyth gwaith cynyddol i staff gofal, a oedd yn gorfod hwyluso apwyntiadau rhithwir, dilyn triniaeth a chyngor a hyd yn oed ardystio marwolaethau.

| “ | Gofynnwyd i un o’n haelodau staff ardystio marwolaeth menyw drwy alwad ffôn. Ac roedd hi fel, ‘Dydw i ddim wedi cael hyfforddiant i wneud hynny.’ Mae hi ar y ffôn yn ffonio’r meddyg teulu wrth geisio cysuro’r teulu ac mae hi’n dweud, ‘Wel, gwaith y meddyg ydy o, nid fy un i’.”

– Rheolwr cofrestredig, Lloegr |

| “ | Roedd y baich yn drwm ar bob un ohonom oherwydd roedd hyd yn oed ceisio cael meddyg allan yn anodd iawn oherwydd eu bod nhw'n brin, felly'r effaith gynyddol o'r ysbyty, y meddygon, y meddygon teulu - pawb - daeth i lawr, wyddoch chi? Fel dominos.”

– Gweithiwr cartref gofal, Lloegr |

- Mae hysbysiadau DNACPR yn benderfyniadau a wneir naill ai gan y clinigwr (lle byddai adfywio cardiopwlmonaidd (CPR) yn aflwyddiannus a/neu heb fod er budd y claf) a/neu lle mae'r claf (gyda'r gallu) yn nodi y byddai'n well ganddo beidio â chael CPR. Felly, ni fydd CPR yn cael ei geisio pan fydd DNACPR ar waith os bydd claf yn cael ataliad ar y galon.

Cofnod llawn

1. Rhagymadrodd

Mae'r ddogfen hon yn cyflwyno'r straeon sy'n ymwneud â gofal cymdeithasol i oedolion yn ystod y pandemig sydd wedi'u rhannu gyda Every Story Matters.

Cefndir a nodau

Mae Every Story Matters yn gyfle i bobl ledled y DU rannu eu profiad o'r pandemig gydag Ymchwiliad Covid-19 y DU. Mae pob stori a rennir yn cael ei dadansoddi a'i throi'n gofnodion thema ar gyfer modiwlau perthnasol. Cyflwynir y cofnodion hyn i'r Ymchwiliad fel tystiolaeth. Wrth wneud hynny, bydd canfyddiadau ac argymhellion yr Ymchwiliad yn cael eu llywio gan brofiadau'r rhai yr effeithiwyd arnynt gan y pandemig.

Mae'r cofnod hwn yn adlewyrchu profiadau pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth (gan gynnwys y rhai sydd wedi marw), teulu a ffrindiau a ofalodd amdanynt a phobl sy'n gweithio ym maes gofal cymdeithasol.

Mae Ymchwiliad Covid-19 y DU yn ystyried gwahanol agweddau ar y pandemig a sut y gwnaeth effeithio ar bobl. Mae hyn yn golygu y bydd rhai pynciau'n cael eu trafod mewn cofnodion eraill o Every Story Matters. Er enghraifft, mae profiadau o ofal iechyd, y system brofi ac olrhain a'r effeithiau ar blant a phobl ifanc yn cael eu harchwilio mewn modiwlau eraill a byddant yn cael eu cynnwys mewn cofnodion eraill o Every Story Matters.

Sut mae pobl yn rhannu eu profiadau

Mae sawl ffordd wahanol rydyn ni wedi casglu straeon pobl ar gyfer Modiwl 6. Mae hyn yn cynnwys:

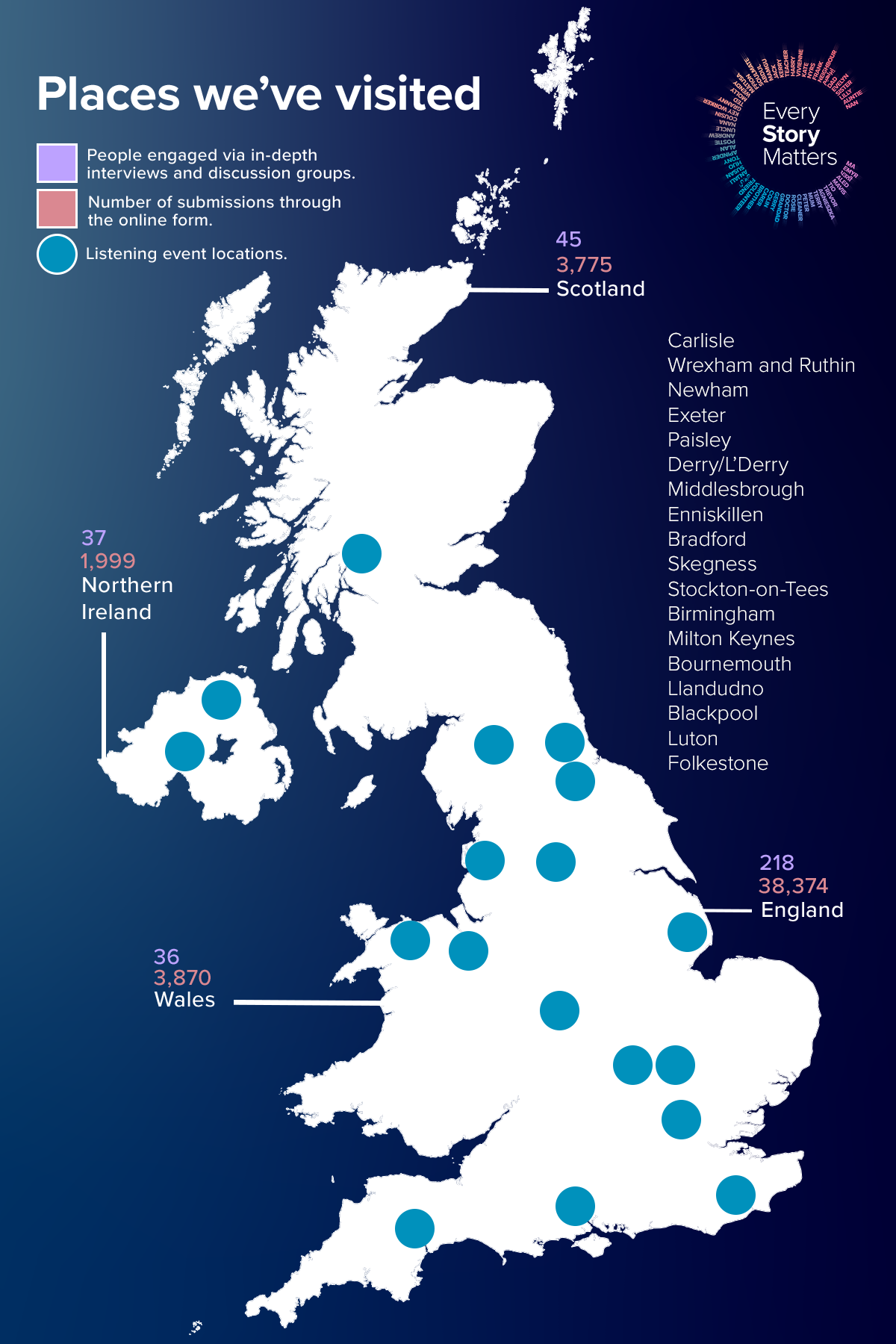

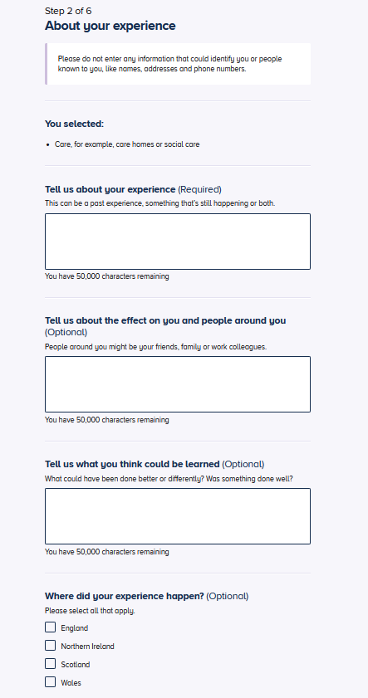

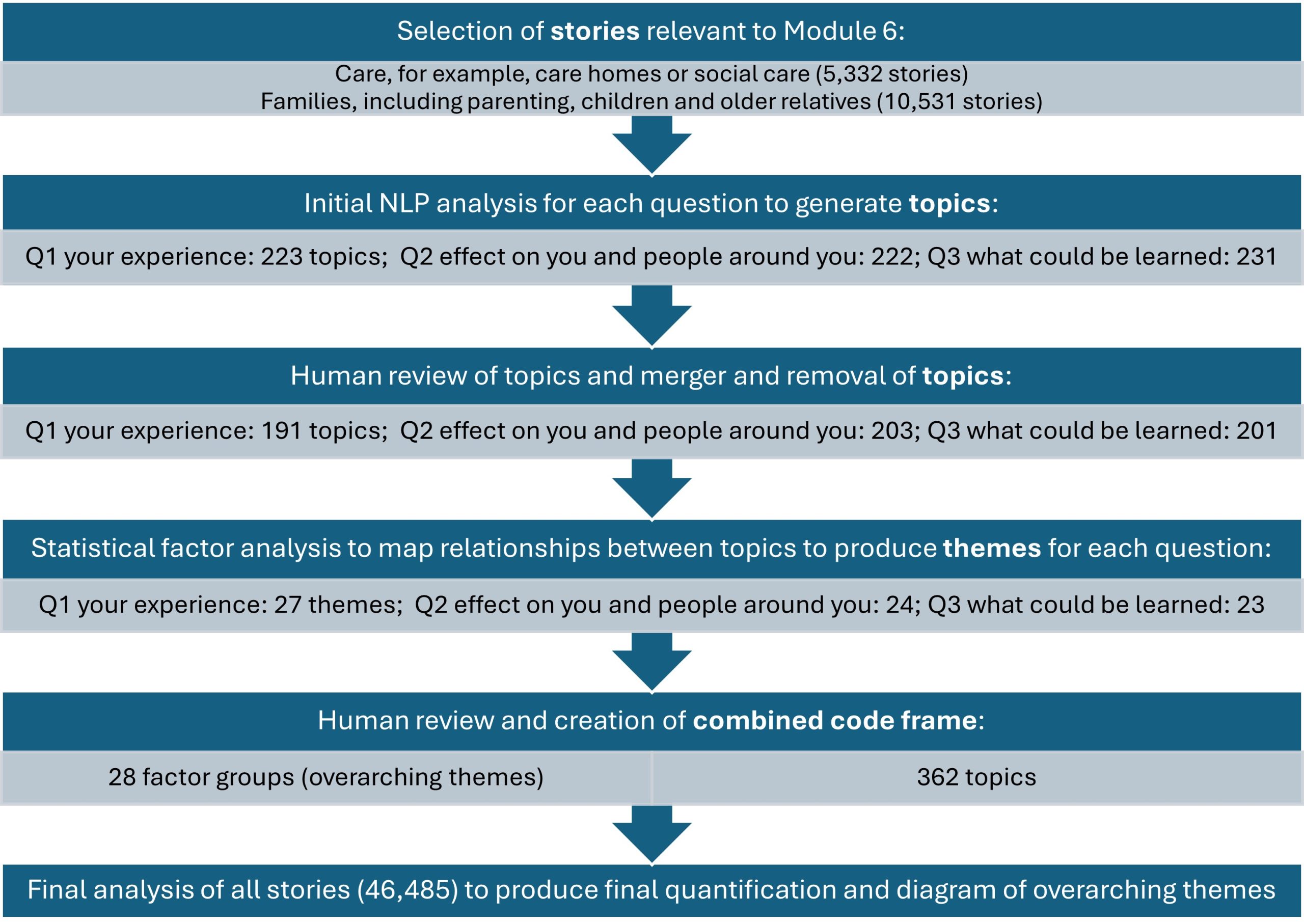

- Gwahoddwyd aelodau'r cyhoedd i gwblhau a ffurflen ar-lein drwy wefan yr Ymchwiliad (cynigiwyd ffurflenni papur i gyfranwyr hefyd a'u cynnwys yn y dadansoddiad). Gofynnodd hyn iddynt ateb tri chwestiwn eang, agored am eu profiad o’r pandemig. Gofynnodd y ffurflen gwestiynau eraill i gasglu gwybodaeth gefndirol amdanynt (megis eu hoedran, rhyw ac ethnigrwydd). Roedd hyn yn caniatáu inni glywed gan nifer fawr iawn o bobl am eu profiadau o’r pandemig. Cyflwynwyd yr ymatebion i’r ffurflen ar-lein yn ddienw. Ar gyfer Modiwl 6, dadansoddwyd 46,485 o straeon a oedd wedi dod i law erbyn i’r cofnod hwn gael ei baratoi. Roedd hyn yn cynnwys 38,374 o straeon o Loegr, 3,775 o’r Alban, 3,870 o Gymru ac 1,999 o Ogledd Iwerddon². Dadansoddwyd yr ymatebion drwy 'brosesu iaith naturiol' (NLP), sy'n helpu i drefnu'r data mewn ffordd ystyrlon. Drwy ddadansoddi algorithmig, trefnir y wybodaeth a gasglwyd yn 'bynciau' yn seiliedig ar dermau neu ymadroddion. Yna adolygwyd y pynciau hyn gan ymchwilwyr i archwilio'r straeon ymhellach (gweler yr Atodiad am fwy o fanylion). Defnyddiwyd y pynciau a'r straeon hyn wrth baratoi'r cofnod hwn.

- Aeth tîm Every Story Matters i 31 o drefi a dinasoedd ledled Lloegr, yr Alban, Cymru a Gogledd Iwerddon i roi cyfle i bobl rannu eu profiad o’r pandemig yn bersonol yn eu cymunedau lleol. Cynhaliwyd sesiynau gwrando rhithwir ar-lein hefyd, os oedd y dull hwnnw’n cael ei ffafrio. Buom yn gweithio gyda llawer o elusennau a grwpiau cymunedol ar lawr gwlad i siarad â’r rhai yr effeithiwyd arnynt gan y pandemig mewn ffyrdd penodol. Ysgrifennwyd adroddiadau crynodeb byr ar gyfer pob digwyddiad, rhannwyd hwy gyda chyfranogwyr y digwyddiad a’u defnyddio i lywio’r ddogfen hon. Ar gyfer y cofnod hwn am ofal cymdeithasol, cynhwyswyd cyfraniadau o 18 o’r digwyddiadau wyneb yn wyneb hyn, yn ogystal â digwyddiadau ar-lein ychwanegol.

- Comisiynwyd consortiwm o arbenigwyr ymchwil gymdeithasol a chymunedol gan Every Story Matters i gynnal cyfweliadau manwl i ddeall profiadau grwpiau penodol, yn seiliedig ar yr hyn yr oedd tîm cyfreithiol y modiwl eisiau ei ddeall. Cynhaliwyd cyfweliadau â phobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth, y rhai sy'n darparu gofal a chymorth di-dâl (gan gynnwys anwyliaid, ffrindiau a theuluoedd sydd wedi colli rhywun) a'r rhai sy'n gweithio ym maes gofal cymdeithasol, boed yn darparu gofal cartref (gofal a ddarperir yng nghartref rhywun ei hun) neu'n gweithio mewn cartref gofal (gan gynnwys gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol a weithiodd yn agos gyda darparwyr gofal cymdeithasol). Canolbwyntiodd y cyfweliadau hyn ar y Prif Linellau Ymholi (KLOEs) ar gyfer Modiwl 6, y gellir eu canfod ymaAt ei gilydd, cyfrannodd 336 o bobl ledled Cymru, Lloegr, yr Alban a Gogledd Iwerddon yn y ffordd hon rhwng Mehefin a Hydref 2024. Cafodd yr holl gyfweliadau manwl eu recordio, eu trawsgrifio, eu codio a'u dadansoddi i nodi themâu allweddol sy'n berthnasol i Gyfweliadau Byw'n Deg Modiwl 6. Rhannodd y rhai a gymerodd ran eu profiadau eu hunain a myfyrio hefyd ar brofiadau eraill. Mae hyn yn golygu, trwy deulu ac anwyliaid a'r gweithlu gofal cymdeithasol, ein bod wedi clywed straeon y rhai ag anghenion gofal a chymorth nad oeddent yn gallu cymryd rhan eu hunain neu a fu farw yn ystod neu ar ôl y pandemig.

² Roedd cyfranwyr yn gallu dewis mwy nag un genedl yn y DU yn y ffurflen ar-lein, felly mae'r cyfanswm a grynhowyd ar draws y gwledydd yn uwch na chyfanswm gwirioneddol yr ymatebion a dderbyniwyd.

Dangosir isod nifer y bobl a rannodd eu straeon ym mhob gwlad yn y DU drwy'r ffurflen ar-lein, digwyddiadau gwrando a chyfweliadau ymchwil:

Ffigur 1: Ymgysylltiad Mae Pob Stori o Bwys ledled y DU

I gael rhagor o wybodaeth am sut y gwnaethom wrando ar bobl a’r dulliau a ddefnyddiwyd i ddadansoddi straeon, gweler yr atodiad.

Cyflwyno a dehongli straeon

Mae'n bwysig nodi nad yw'r straeon a gasglwyd drwy Every Story Matters yn gynrychioliadol o bob profiad o ofal cymdeithasol yn ystod y pandemig ac rydym yn debygol o glywed gan bobl sydd â phrofiad penodol i'w rannu gyda'r Ymchwiliad, yn enwedig ar y ffurflen we ac mewn digwyddiadau gwrando. Effeithiodd y pandemig ar bawb yn y DU mewn gwahanol ffyrdd ac, er bod themâu a safbwyntiau cyffredinol yn dod i'r amlwg o'r straeon, rydym yn cydnabod pwysigrwydd profiad unigryw pawb o'r hyn a ddigwyddodd. Nod y cofnod hwn yw adlewyrchu'r gwahanol brofiadau a rannwyd gyda ni, heb geisio cymodi'r gwahanol straeon.

Rydym wedi ceisio adlewyrchu'r amrywiaeth o straeon a glywsom, a allai olygu bod rhai straeon a gyflwynir yma yn wahanol i'r hyn a brofodd pobl eraill, neu hyd yn oed llawer o bobl eraill, yn y DU. Lle bo'n bosibl rydym wedi defnyddio dyfyniadau i helpu i seilio'r cofnod ar yr hyn a rannodd pobl yn eu geiriau eu hunain.

Archwilir rhai straeon yn fanylach trwy ddarluniau achos o fewn y prif benodau. Mae'r rhain wedi'u dewis i amlygu'r gwahanol fathau o brofiadau y clywsom amdanynt a'r effaith a gafodd y rhain ar bobl. Mae cyfraniadau wedi'u hanonymeiddio trwy ddefnyddio ffugenwau (yn hytrach nag enw go iawn y person).

Rydym hefyd wedi datblygu astudiaethau achos (Pennod 8), gan ddod â straeon gwahanol grwpiau o fewn lleoliad penodol ynghyd yn seiliedig ar ymweliadau personol â darparwyr gofal. Mae'r astudiaethau achos hyn yn rhoi cipolwg dyfnach ar y gwahanol fathau o brofiadau o fewn darparwyr gofal o wahanol safbwyntiau.

Drwy gydol y cofnod, rydym yn cyfeirio at bobl a rannodd eu straeon gyda Every Story Matters fel 'cyfranwyr'. Lle bo'n briodol, rydym hefyd wedi disgrifio mwy amdanynt (er enghraifft, eu rôl neu leoliad gofal) i helpu i egluro cyd-destun a pherthnasedd eu profiad. Rydym hefyd wedi cynnwys y genedl yn y DU y mae'r cyfrannwr yn dod ohoni (lle mae'n hysbys). Nid yw hyn wedi'i fwriadu i roi darlun cynrychioliadol o'r hyn a ddigwyddodd ym mhob gwlad, ond i ddangos y profiadau amrywiol ledled y DU o bandemig Covid-19. Casglwyd a dadansoddwyd straeon drwy gydol 2024, sy'n golygu bod profiadau'n cael eu cofio rywbryd ar ôl iddynt ddigwydd.

Mewn rhai mannau yn y cofnod, rydym yn adlewyrchu'r hyn a ddywedodd pobl wrthym am y berthynas waith rhwng gwasanaethau iechyd a gofal cymdeithasol yn ystod y pandemig. Mae profiadau'r system gofal iechyd yn ystod y pandemig wedi'u manylu yng nghofnod Modiwl 3. Mae'r cofnod hwn yn canolbwyntio ar brofiadau'r sector gofal cymdeithasol ac nid yw'n ceisio cymodi gwahanol safbwyntiau.

Strwythur y cofnod

Mae'r ddogfen hon wedi'i strwythuro i ganiatáu i ddarllenwyr ddeall sut brofiad oedd gan bobl o ofal cymdeithasol. Mae'r cofnod wedi'i drefnu'n thematig gyda phrofiad pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth, anwyliaid, gofalwyr di-dâl a'r gweithlu gofal cymdeithasol a geir ar draws pob pennod:

- Pennod 2: Cyfnodau clo a chyfyngiadau ar leoliadau gofal

- Pennod 3: Rhyddhau o ysbytai i gartrefi gofal

- Pennod 4: Gofal diwedd oes a phrofedigaeth

- Pennod 5: PPE a mesurau rheoli heintiau

- Pennod 6: Prinder staff a sut y darparwyd gofal

- Pennod 7: Mynediad at wasanaethau gofal iechyd a phrofiad ohonynt

- Pennod 8: Astudiaethau achos.

Terminoleg a ddefnyddir yn y cofnod

Defnyddir y termau a'r ymadroddion canlynol drwy gydol y cofnod i gyfeirio at grwpiau allweddol neu bolisïau ac arferion penodol a oedd yn berthnasol i'r sector gofal cymdeithasol yn ystod pandemig Covid-19. Rydym yn disgrifio gweithgareddau a lleoliadau gofal, mathau o anghenion gofal, y rhai sy'n darparu gofal a chymorth, ac yna rhai termau penodol a ddefnyddir yn y sector gofal cymdeithasol.

Gofal cymdeithasol i oedolion yn disgrifio cymorth gyda thasgau dyddiol fel y gall pobl fyw mor annibynnol â phosibl. Mae ar gyfer oedolion a allai fod angen cymorth ychwanegol oherwydd oedran, anabledd, salwch neu gyflyrau iechyd meddwl a chorfforol eraill. Gall gofal cymdeithasol oedolion helpu gyda thasgau dyddiol fel paratoi prydau bwyd, golchi a gwisgo, mynd i'r toiled a gofal personol arall i bobl hŷn ac oedolion o oedran gweithio. Gall hefyd gynnwys cymorth gyda chludiant fel y gall pobl deithio o gwmpas eu cymuned leol a chefnogaeth ar gyfer ynysu cymdeithasol ac unigrwydd. Gellir darparu gofal cymdeithasol oedolion mewn sawl lleoliad gwahanol. Ar gyfer Pob Stori yn Bwysig, canolbwyntiodd Modiwl 6 yn bennaf ar gartrefi gofal a gofal cartref.

Gofal cartref a elwir hefyd yn ofal cartref. Mae'n cynnwys gweithiwr gofal yn ymweld â chartref person i gefnogi gyda thasgau dyddiol fel rhoi meddyginiaethau, golchi a gwisgo, paratoi bwyd a glanhau'r cartref. Nod gofal cartref yw helpu pobl i fyw'n annibynnol yn eu cartref eu hunain ac i gynnal ansawdd eu bywyd.

Cartrefi gofal yn lleoedd lle mae pobl yn byw i dderbyn cymorth ychwanegol gyda gofal personol fel bwyta, golchi, gwisgo a chymryd meddyginiaeth. Mae gwahanol fathau o gartrefi gofal. Mae rhai yn cynnig gofal nyrsio neu ofal dementia arbenigol tra nad yw eraill yn gwneud hynny ac efallai y byddant yn cael eu hadnabod fel cartrefi gofal preswyl.

Pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth yn bobl 18 oed a throsodd sydd angen cymorth gyda gweithgareddau dyddiol gan gynnwys gofal personol a thasgau domestig oherwydd cyflyrau iechyd corfforol neu feddyliol, oedran neu anabledd. Gall hyn gynnwys pobl sydd:

- Oes gennych chi anabledd dysgu

- Yn awtistig

- Yn cael eu heffeithio gan gyflwr iechyd meddwl

- Yn cael eu heffeithio gan Ddementia

- Yn fregus oherwydd afiechyd neu anabledd corfforol.

Gofalwyr di-dâl yn aelodau o'r teulu neu'n ffrindiau sy'n gofalu am rywun sydd ag anghenion gofal a chymorth. Gall gofalu am rywun olygu ychydig oriau bob wythnos neu efallai eu bod yn gofalu amdano 24 awr y dydd, saith diwrnod yr wythnos. Mae rhai gofalwyr di-dâl yn byw gyda'r person maen nhw'n gofalu amdano neu'n agos ato tra gall eraill ddarparu mwy o gymorth o bell. Gall rhai gofalwyr di-dâl ofalu am fwy nag un person. Yn y cofnod rydym hefyd yn defnyddio'r term 'rhywun annwyl' ar gyfer pobl y mae aelod o'u teulu mewn cartref gofal ac efallai nad yw'n darparu gofal o ddydd i ddydd. Lle cafodd y person brofedigaeth yn ystod y pandemig, defnyddir y term hwn hefyd i ddisgrifio'r gofalwyr di-dâl neu'r anwyliaid.

Gweithwyr gofal cymdeithasol proffesiynol cefnogi pobl sydd ag anghenion gofal a chymorth. Mae hyn yn cynnwys sawl rôl broffesiynol gan gynnwys gweithwyr gofal, rheolwyr cofrestredig a gweithwyr cymdeithasol a ddisgrifir isod.

Gweithwyr gofal yn weithwyr proffesiynol sy'n cefnogi pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth i fyw'n annibynnol a chyflawni gweithgareddau dyddiol. Gall hyn gynnwys helpu gyda bwyta ac yfed, cynorthwyo gyda gofal personol, archebu neu fynd gyda phobl i apwyntiadau a helpu gyda meddyginiaethau.

Rheolwr cofrestredig yn rôl reoli sy'n ofynnol gan y Comisiwn Ansawdd Gofal ar gyfer pob lleoliad gofal cofrestredig gan gynnwys cartrefi gofal a darparwyr gofal cartref.

Gweithwyr cymdeithasol yn weithwyr proffesiynol sy'n cefnogi pobl agored i niwed i'w hamddiffyn rhag niwed neu gam-drin ac maen nhw'n helpu pobl i fyw'n annibynnol. Maen nhw'n gweithio gyda phobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth, eu hanwyliaid a gweithwyr proffesiynol eraill i helpu i lywio heriau. Gall hyn gynnwys asesu anghenion pobl, trefnu cymorth a gwneud atgyfeiriadau at wasanaethau eraill.

Offer Diogelu Personol yw PPE sy'n cynnwys masgiau, menig, ffedogau a fisorau.

Gwisgo a thynnu i ffwrdd yw'r term a ddefnyddir am wisgo a thynnu PPE i ffwrdd, yn y drefn honno.

2. Roedd cyfranwyr yn gallu dewis mwy nag un genedl yn y DU yn y ffurflen ar-lein, felly mae'r cyfanswm a grynhowyd ar draws y gwledydd yn uwch na chyfanswm gwirioneddol yr ymatebion a dderbyniwyd.

2. Cloeon a chyfyngiadau ar leoliadau gofal |

|

Mae'r bennod hon yn archwilio effeithiau cyfyngiadau'r cyfnod clo ar ofal cymdeithasol i oedolion. Mae'n disgrifio effeithiau peidio â gallu ymweld â phobl sy'n byw gartref neu eu cefnogi a'r pwysau ar ofalwyr di-dâl. Mae hefyd yn edrych ar gyfyngiadau ar ymweliadau â chartrefi gofal a symud o fewn cartrefi gofal a sut yr effeithiodd y newid i gyfathrebu rhithwir ar y sector gofal cymdeithasol i oedolion.

Sut effeithiodd cyfyngiadau symud ar ofal a chymorth gartref

Sut effeithiodd trefniadau byw ar brofiadau cyfnod clo

Roedd pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth nad oedd ganddynt unrhyw gymorth ffurfiol yn ystod y pandemig yn wynebu heriau difrifol a oedd yn eu gadael dan straen, yn flinedig ac yn ynysig.

| “ | Rwy'n anabl ac mae gen i glefyd hunanimiwn terfynol, felly roeddwn i'n amddiffyn fy hun…Yn ystod y pandemig, roeddwn i'n teimlo ar goll, ynysig, unig, wedi'm hanghofio ac yn ofnus…Er bod fy chwaer a'i theulu'n byw drws nesaf, wnaethon ni ddim cwrdd ond cawsom alwad ffôn ddyddiol am 10 munud wrth iddi ofalu am ei merch anabl, felly roeddwn i'n brysur iawn.”

- Person ag anghenion gofal a chymorth, Lloegr |

Roedd pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth a oedd yn byw ar eu pen eu hunain yn ei chael hi'n anodd ymdopi â thasgau sylfaenol fel coginio a golchi, a oedd yn eu gwneud nhw'n teimlo'n ddiymadferth ac wedi'u gadael ar adegau.Roedd rhaid i'r cyfranwyr hyn naill ai ddod o hyd i ffyrdd o ymdopi ar eu pen eu hunain neu roeddent yn ddibynnol ar gefnogaeth gyfyngedig iawn. Gadawyd pobl a oedd wedi byw'n annibynnol o'r blaen gyda chefnogaeth ac ymweliadau mynych gan deulu a ffrindiau heb neb i gadw llygad ar sut roeddent yn ymdopi.

| “ | Roeddwn i'n gaeth i'r gwely felly allwn i ddim hyd yn oed goginio, felly am ychydig ddyddiau doeddwn i ddim wedi coginio na bwyta dim byd, felly fe wnaeth un o fy ffrindiau goginio pryd o fwyd a'i adael wrth y drws ffrynt, canu'r gloch ac yna gadael.”

- Person ag anghenion gofal a chymorth, Lloegr |

| “ | Roedd yn lletchwith weithiau os yw hynny'n gwneud synnwyr, roeddwn i'n dal yn gallu rhoi fy mwyd fy hun ymlaen ac ati. Mae'n rhaid i mi gael fy ngwylio am adael y nwy ymlaen. Rydw i wedi gwneud hynny sawl gwaith.”

- Person ag anghenion gofal a chymorth, Lloegr |

Myfyriodd pobl sy'n defnyddio gwasanaethau gofal cartref ac sy'n byw ar eu pen eu hunain hefyd ar sut unig ac ynysig roedden nhw'n teimlo. Yn aml, yr unig berson yr oeddent yn rhyngweithio ag ef oedd eu gweithiwr gofal cartref.

| “ | Roedd ochr unigedd pethau'n real iawn oherwydd fy mod i'n byw ar fy mhen fy hun, felly, cyn iddyn nhw gyflwyno'r syniad o swigod, roeddwn i'n teimlo'n ynysig iawn. Felly, yr unig bobl roeddwn i'n cael cymysgu â nhw oedd fy ngofalwyr [cartref]. Y peth pwysicaf oedd unigedd difrifol.”

- Person ag anghenion gofal a chymorth, Lloegr |

Cafodd teuluoedd, ffrindiau a gofalwyr di-dâl eu hatal rhag ymweld â phobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth nad oeddent yn byw gyda nhw oherwydd cyfyngiadau'r cyfnod clo. Nhw yn poeni'n fawr am y bobl yr oeddent yn gofalu amdanynt ac yn ofni am eu lles a'u diogelwch.

| “ | [Wnes i ddim gweld fy nhad am] 112 diwrnod ar gyfer y cyfnod clo cyntaf. Yn y pen draw, newidiodd y syniad y gallech chi fynd i dŷ rhywun os oeddech chi'n gofalu amdanyn nhw ond i ddechrau nid oedd hynny'n bosibl o gwbl.”

- Gofalwr di-dâl yn byw ar wahân i'r person y maent yn gofalu amdano, yr Alban |

Ar gyfer gofalwyr di-dâl a oedd yn byw ar wahân i'w hanwyliaid, roedd y cyswllt wedi'i gyfyngu i sgyrsiau ffôn neu ar-lein neu adael hanfodion fel siopa bwyd ar garreg y drwsRoedd gofalwyr di-dâl yn ei chael hi'n heriol ac yn llawn straen i drefnu gofal i bobl nad oeddent yn byw gyda nhw.

| “ | Mae fy mam a fy nhad yn eu 70au, ac nid Saesneg yw eu hiaith gyntaf… byddwn i’n mynd i’w tŷ, a byddwn i’n sefyll y tu allan… bydden nhw ar garreg y drws a byddem ni’n siarad am, beth ydych chi wedi’i wneud, ydych chi wedi ffonio’r gofalwyr? Beth maen nhw’n ei gynnig? Ydyn nhw’n dod o hyd? Ydych chi eisiau i mi eu ffonio nhw?”

- Gofalwr di-dâl yn byw ar wahân i'r person y maent yn gofalu amdano, Lloegr |

Disgrifiodd llawer o bobl deimlo'n rhwygo rhwng yr awydd i dreulio amser gyda'u hanwyliaid a'r awydd i'w hamddiffyn rhag haint Covid-19 posibl.Achosodd rheoli'r tensiwn rhwng risgiau haint Covid-19 a risgiau gadael aelodau'r teulu heb gefnogaeth ofid mawr ar y pryd. Wrth fyfyrio ar hyn ar ôl y pandemig, roedd rhai'n difaru dilyn cyfyngiadau a pheidio â threulio mwy o amser gyda'r person yr oeddent yn gofalu amdano, yn enwedig y rhai sydd wedi cael profedigaeth. Mae aelodau'r teulu a gofalwyr di-dâl yn parhau i deimlo'n edifeirwch ac yn ofidus am yr amser a gollwyd ganddynt.

| “ | Fyddwn i ddim yn treulio cymaint ag y byddwn i wedi hoffi, byddai hi'n dweud, “O, rhowch y tegell ymlaen, cael paned o de gyda fi” ac [doeddwn i ddim yn gallu…] Yr holl bethau hyn rydych chi'n difaru wedyn roedd yn anodd; roedd hi'n unig.”

- Gofalwr di-dâl yn byw ar wahân i'r person y maent yn gofalu amdano, Cymru |

| “ | Roeddwn i wedi dilyn y rheolau o ddechrau'r cyfnod clo ac ni wnes i ymweld â fy rhieni, rhywbeth rwy'n ei ddifaru nawr, gan nad oedd yr un ohonom wedi dal Covid a byddai wedi bod yn ddiogel eu cael yn ein swigen ni. Rwy'n teimlo fy mod i wedi colli allan ar rai wythnosau pwysig iawn ar ddiwedd bywyd iach mam.”

- Gofalwr di-dâl yn byw ar wahân i'r person y maent yn gofalu amdano, Lloegr |

Mewn rhai achosion, gwnaeth anwyliaid a gofalwyr di-dâl y penderfyniad i dorri cyfyngiadau er mwyn iddynt allu cynnal cysylltiad neu ddarparu gofal hanfodol i'r person yr oeddent yn gofalu amdano. Weithiau byddai rheolau’n cael eu torri os oeddent yn byw mewn ardal wahanol ac roedd cyfyngiadau ar deithio rhwng ardaloedd mewn gwahanol haenau o’r cyfnod clo. Fodd bynnag, roedd torri cyfyngiadau’r cyfnod clo i wneud hyn hefyd yn ffynhonnell o poeni.

| “ | Dylwn i fod wedi cael mynd i mewn i dŷ fy mam-gu a'i eistedd gyda hi a rhyngweithio llawer mwy na gadael y siopa wrth ei drws ffrynt ac yna ei gario allan i'r ardd. Ar ôl ychydig, torrais y rheolau oherwydd gwelais pa mor gyflym yr oedd hi'n dirywio a meddyliais, 'Does dim ffordd ar y blaned hon na fyddaf yn mynd i mewn i weld fy mam-gu. Dydw i ddim yn mynd i'w wneud.'”

- Gofalwr di-dâl yn byw ar wahân i'r person y maent yn gofalu amdano, Lloegr |

| “ | Roedd gan fy nhad glefyd niwronau modur ac yn ystod Covid roedden ni'n teimlo fel pe bai wedi'i adael i ofalu amdano'i hun. Roedd yng nghyfnodau diweddarach y clefyd ac yn cael trafferth mawr gyda symudedd. Gadawyd gofal dyddiol fy nhad i fy mam sydd hefyd â chyflwr iechyd cronig. Pan fu bron â chael chwalfa oherwydd straen gofalu am fy nhad, torrais reolau'r cyfnod clo i helpu i ofalu amdano.”

- Gofalwr di-dâl, Lloegr |

Stori AndyMae Andy yn byw yn yr Alban ac yn darparu gofal i'w neiniau a theidiau yn ystod y pandemig. Nid oedd yn byw yn agos atynt. Myfyriodd ar ba mor anodd oedd penderfynu a ddylid dilyn cyfyngiadau'r cyfnod clo neu flaenoriaethu gofal ei neiniau a theidiau. Roedd ei benderfyniad i ymweld â nhw yn golygu ei fod yn aml yn teimlo'n bryderus ac yn llawn straen. |

|

| “ | Roeddwn i'n torri'r rheolau bob dydd, ond roeddwn i fel, 'Gallan nhw fy nirwyo, gallant fy rhoi yng nghefn car heddlu yn llythrennol.' Felly, cafodd effaith andwyol ar fy iechyd, ond beth yw rhan fach o'r effaith andwyol honno o'i gymharu â'r magwraeth a roddodd [fy nhaid a theidiau] i mi, y cariad, y gofal, y gefnogaeth.” |

| Roedd Andy hefyd yn poeni'n fawr am drosglwyddo Covid-19 i'w neiniau a theidiau pan ymwelodd â nhw, i'r graddau y byddai'n effeithio ar ei gwsg. | |

| “ | Roeddwn i'n deffro am 2 o'r gloch, 3 o'r gloch, 4 o'r gloch y bore gyda chrychguriadau'r galon, chwysu, dan straen, 'Ydw i'n mynd i roi Covid iddyn nhw?' Roeddwn i'n gwneud 2 neu 3 prawf y dydd a phethau fel 'na cyn i mi fynd drwodd i'w gweld nhw.” |

| Pan oedd nain Andy yn marw, anwybyddodd ei deulu'r rheolau i sicrhau y gallent fod gyda hi. | |

| “ | Fe wnaethon ni dorri pob rheol dan yr haul a theithiodd fy modryb i fyny. Ei chwaer hi yw hi, fel y gwyddoch chi. Mae ei chwaer yn marw ac roedden ni i gyd yn teimlo fel pe baen ni wedi eu siomi gymaint yn ystod [y pandemig] a bod y system wedi eu siomi. Doedden ni ddim am eu siomi.” |

Penderfynodd gofalwyr di-dâl eraill symud, i fyw gyda'r person yr oeddent yn gofalu amdano, er mwyn sicrhau y gallent ddarparu'r gefnogaeth oedd ei hangen.Profodd rhai ymdeimlad mwy o undod ac agosrwydd gyda'u teulu oherwydd eu bod wedi treulio cymaint o amser gyda'i gilydd. Yn gysylltiedig â hyn, roeddent yn ddiolchgar iawn am y cyfle a gawsant i dreulio amser gyda'u hanwyliaid a gofalu amdanynt.

| “ | Cafodd fy nhad ei ryddhau cyn y cyfnod clo oherwydd bod yr ysbyty yn gwybod y byddai'n fwy diogel gartref. Doedd e ddim yn teimlo'n ddiogel cael gofalwyr felly symudais i mewn gyda fy rhieni… Am chwe mis, gwnes i'r rhan fwyaf o bethau i fy nhad. Tynnais ei bad anymataliaeth bob bore, ei olchi a'i eillio bob dydd. …Roedd yn fraint gofalu amdano.”

- Gofalwr di-dâl a symudodd i mewn gyda'r person yr oeddent yn gofalu amdano, Lloegr |

| “ | Roedd gofalu am fy nain yn anodd iawn, ond ar yr un pryd, rwy'n ddiolchgar fy mod i wedi cael ei wneud… Rwy'n gwybod ei fod wedi fy ngwthio i lawr a phopeth, ond… Rwy'n teimlo'n ddiolchgar iawn bod yr un person a'm helpodd pan oeddwn i'n fabi, wedi fy magu, wedi gwneud cymaint i mi ac yna fi yn tyfu i fyny a gallu gofalu amdanyn nhw… Rwy'n ei chael yn fendith.”

- Gofalwr di-dâl a symudodd i mewn gyda'r person yr oeddent yn gofalu amdano, Lloegr |

Dywedodd pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth wrthym fod byw gyda theulu neu ofalwyr wedi gwneud addasu i'r cyfyngiadau symud yn haws. Roedd cael rhywun i siarad ag ef a'u cefnogi gyda'u hanghenion gofal yn gwneud pethau'n haws i'w rheoli. Rhannodd cyfranwyr enghreifftiau o'u teuluoedd ac eraill yn gwneud iawn am fynediad llai at wasanaethau iechyd a gofal cymdeithasol yn ystod y pandemig. Siaradodd rhai yn gynnes am ba mor dda y gofalwyd amdanynt a'u cefnogi a gwerthfawrogasant yr amser y gallent ei dreulio gyda'i gilydd. O ganlyniad, roedd rhai pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth yn edrych yn ôl ar yr amser hwn gyda rhywfaint o hoffter.

| “ | O ran y gofal rwy'n ei dderbyn, oherwydd ein bod wedi llwyddo i gael fy merch adref cyn y cyfnod clo ac yn amlwg ni allai fy ngwraig wneud unrhyw waith o gwbl nes i'r cyfnod clo lacio, roedd gen i ddau oedolyn yn y tŷ mewn gwirionedd ar gyfer y gofal dyddiol ychwanegol ... ond ie, o ran fy ngofal dyddiol gwirioneddol, roedd yn well ... ac yn amser hapus.”

- Person ag anghenion gofal a chymorth, Lloegr |

Stori HalemaMae Halema yn 74 oed ac yn byw yng Nghanolbarth Lloegr. Mae ganddi glefyd rhwystrol cronig yr ysgyfaint (COPD) sy'n cyfyngu ar ei hanadlu. Mae ganddi reolydd calon hefyd a chyflyrau iechyd eraill sy'n gysylltiedig â'i hoedran. Mae hi'n byw ar ei phen ei hun mewn fflat yn agos at ganol y dref. Roedd cyflwyno’r cyfyngiadau symud yn heriol iawn iddi. Roedd hi wedi bod yn aelod o wahanol grwpiau cymunedol o’r blaen, a roddodd hynny drefn iddi a chaniatáu iddi ryngweithio â phobl. Roedd y cyfyngiadau symud yn sioc fawr yr oedd yn anodd addasu iddi. |

|

| “ | Roedd yn newid enfawr peidio â gweld ffrindiau na theulu, roedd yn heriol iawn.” |

| Fodd bynnag, cafodd gefnogaeth gan ei nith a dorrodd gyfyngiadau’r cyfnod clo i ymweld â hi bob dydd i baratoi ei meddyginiaeth a gwneud rhywfaint o fwyd. | |

| “ | Dyw fy iechyd ddim wedi bod yn dda ers amser maith, ond mae wedi gwaethygu o'r holl amser a dreuliais ar fy mhen fy hun y tu mewn. Gwelais lawer mwy ohoni, oherwydd ei bod hi'n dod i lawr yn fwy i wneud yn siŵr fy mod i'n iawn, yn gwneud yr holl bethau y mae hi bob amser wedi'u gwneud, rhywbeth fel, fy nghael i fyny lawer o'r amser, allan o'r gwely, glanhau cyffredinol o amgylch y tŷ. Paratoi bwyd i mi, roedd hi'n arfer gwneud y siopa ar-lein, wel yn bennaf ar-lein, gofalu am y tabledi.” |

| Cryfhaodd y gofal a ddarparodd nith Halema a'r amser a dreuliasant gyda'i gilydd eu perthynas. Mae Halema yn ddiolchgar iawn am yr holl gefnogaeth a gafodd yn ystod y pandemig. | |

| “ | Mae hi wastad wedi gofalu amdanaf, cyn y pandemig, ond mae'r amser hwnnw, wrth edrych yn ôl arno, yn gwneud i mi feddwl pa mor lwcus oeddwn i i'w chael hi a fy ffrindiau eraill a helpodd fi ac a wiriodd sut roeddwn i'n teimlo." |

Teimladau unigrwydd ac arwahanrwydd gofalwyr di-dâl

Roedd rhai gofalwyr di-dâl yn teimlo'n ynysig ac yn gaeth yn eu cartref er gwaethaf y ffaith eu bod yn falch eu bod yn gallu byw gyda'r person yr oeddent yn gofalu amdano. Roedden nhw'n teimlo bod y cyfyngiadau symud yn glaustroffobig, yn llawn straen ac yn teimlo'n llethol gan y gofynion sylweddol a roddwyd arnyn nhw.

| “ | Mae'n rhaid i mi boeni'n gyson am [fy mhartner]. Weithiau roeddwn i'n teimlo braidd yn fygythiad ac yn gaeth, ac nid oedd unrhyw ffordd o ddianc o hynny. Dyna sut roeddwn i'n teimlo ar adegau yn ystod y pandemig oherwydd roeddwn i'n teimlo fel petawn i'n garcharor wedi'i ddal yn fy nghartref fy hun heb ddihangfa.”

- Gofalwr di-dâl yn byw gyda'r person y maent yn gofalu amdano, yr Alban |

| “ | Roedd yn llawn straen i mi, cael plentyn [a fy ngŵr, a oedd â chanser] yn y tŷ. Rydych chi i gyd wedi'ch cyfyngu mewn un lle. Roedd yn rhaid i mi wneud popeth o gwmpas y tŷ. Roeddwn i'n gofalu am y plentyn, rwy'n gofalu am [fy ngŵr], rwy'n gofalu am y tŷ, rwy'n gwneud y pethau ariannol, rwy'n siopa, wyddoch chi? Ac yna doedd gen i ddim amser i mi fy hun.”

- Gofalwr di-dâl yn byw gyda'r person y maent yn gofalu amdano, Lloegr |

Teimlai aelodau'r teulu a gofalwyr di-dâl absenoldeb eu rhwydweithiau cymorth arferolNid oeddent yn gallu gweld ffrindiau nac aelodau eraill o'r teulu ac nid oedd ganddynt gyfleoedd i gael seibiant pan oedd gofalu fwyaf anodd. Roedd hyn yn arbennig o wir am y rhai a symudodd i mewn i ddarparu gofal yn ystod y cyfnod clo ac a oedd i ffwrdd o'u trefn arferol a'u hamgylchedd.

| “ | Pan aeth yn sâl iawn, roedd yn wirioneddol flinedig ac yn frawychus ac yn unig iawn, iawn. Wrth gwrs, byddai pobl yn ffonio ac yn dweud, 'Os oes unrhyw beth y gallem ei wneud' ond nid oedd dim oherwydd, yn y cyfnod [cyflymder clo] cyntaf, nid oeddent yn cael mynd i mewn i'r tŷ. Roeddech chi'n gwbl ynysig.”

- Gofalwr di-dâl yn byw gyda'r person y maent yn gofalu amdano, Cymru |

| “ | Doedd gan yr un ohonom blant…felly symudais i mewn i ofalu amdano…Doeddwn i erioed wedi gwneud unrhyw beth tebyg ac roedd yn wirioneddol ddwys gofalu am rywun oedd yn sâl…heb neb arall…wnaem ni ddim gweld unrhyw deulu na ffrindiau am dros flwyddyn.”

- Gofalwr di-dâl a symudodd i mewn gyda'r person yr oeddent yn gofalu amdano, Lloegr |

| “ | Roedd cael fy nghyfyngu i un amgylchedd…roedd yn eithaf anodd…roedd yn golygu hyd yn oed fi fy hun, wel, roedd cyfyngiadau i fynd allan a sawl gwaith y gallech chi fynd allan, roedd yn cael effaith arnaf i, oherwydd roedd yn golygu, wyddoch chi, eich bod chi'n canolbwyntio ar un person ac mae'n teimlo fel eich bod chi'n esgeuluso popeth arall. Rwy'n credu bod ganddo ryw fath o effaith seicolegol [arnaf i].”

- Gofalwr di-dâl a symudodd i mewn gyda'r person yr oeddent yn gofalu amdano, Lloegr |

Hyd yn oed pan oedd gofalwyr di-dâl ac aelodau o'r teulu yn gallu cymryd seibiannau byr o'r cartref (er enghraifft trwy gerdded y ci neu siopa am fwyd) fel ffordd o ymdopi â phwysau darparu gofal, roedden nhw'n aml yn bryderus iawn am y risg o ddal Covid-19Roeddent yn gyson ar eu gwyliadwriaeth i leihau'r risg iddynt eu hunain a'r bobl yr oeddent yn eu cefnogi.

| “ | Fe wnes i fynd â'r cŵn allan, dyna oedd fy synnwyr cyffredin, rhywfaint o amser i mi fy hun, mwynhau'r golygfeydd heb neb o gwmpas, ond ar yr un pryd [roeddwn i bob amser] yn dal i boeni beth petawn i'n taro i mewn i rywun. Os byddwn i'n ei ddal, yna mae'n bendant yn mynd yn ôl ato ac mae'n fy mai i.”

- Gofalwr di-dâl yn byw gyda'r person y maent yn gofalu amdano, yr Alban |

Roedd pobl oedd yn darparu gofal di-dâl wedi’u llethu gan effeithiau’r cyfyngiadau symud a darparu gofal ar hyd yr oriau. Clywsom am effeithiau negyddol eang a sylweddol ar eu hiechyd corfforol a meddyliolRoedd hyn yn cynnwys straen, blinder a phryder llethol.

| “ | Ar un adeg, dim ond tua phedair awr o gwsg y dydd oeddwn i'n ei gael am fisoedd, ac fe ddaeth yn norm. Roeddwn i'n meddwl fy mod i'n iawn, ond roeddwn i wedi blino'n llwyr.”

- Gofalwr di-dâl yn byw gyda'r person y maent yn gofalu amdano, Gogledd Iwerddon |

| “ | Roedd y gofal parhaus a gwaethygu iechyd [anwylyd] wedi cael effaith arnaf. Roeddwn i'n teimlo dan straen mawr i'r pwynt nes i mi sylweddoli weithiau na allwn i wneud pethau normal, gallaf gofio [i mi geisio] gwagio'r peiriant golchi llestri ac roeddwn i'n ei chael hi'n rhy anodd… Doeddwn i ddim yn gallu ei wneud.”

- Gofalwr di-dâl yn byw gyda'r person y maent yn gofalu amdano, Cymru |

Straeon gan ofalwyr di-dâlClywsom hefyd mewn digwyddiad ar-lein gyda Carers UK sut yr effeithiodd pwysau darparu gofal yn ystod y pandemig ar iechyd meddwl a lles pobl. |

|

| “ | Y baich o weithio efallai 14 neu 15 awr y dydd, saith diwrnod yr wythnos a gofalu am fy rhieni oedd ill dau yn gwarchod fy hun, cefais fy llosgi allan. Un diwrnod, dechreuais grio.”

– Gofalwr di-dâl, digwyddiad gwrando, Gogledd Iwerddon |

Clywsom am effaith cymryd cyfrifoldebau gofalu ychwanegol a arweiniodd at anwyliaid a gofalwyr di-dâl yn mabwysiadu arferion afiach i ymdopi. Roedd hyn yn cynnwys mwy o yfed alcohol a newidiadau mewn diet.

Stori SallyYn ystod y pandemig, bu Sally yn byw yn yr Alban, gan ddarparu gofal a chefnogaeth i'w mab sy'n oedolyn a'i dau riant. Gadawodd gofynion gofalu am aelodau ei theulu hi'n teimlo'n flinedig ac effeithiodd ar ei hiechyd corfforol a meddyliol. |

|

| “ | Saethodd fy mhwysedd gwaed drwy’r to a hyd yn oed nawr mae’n rhaid i mi gymryd lefel uchel iawn o feddyginiaeth pwysedd gwaed uchel.” |

| Mae mab Sally yn gwadriplegig. Cyn y pandemig, roedd ganddo ofal 24 awr ac roedd angen tri gofalwr arno i'w symud i mewn ac allan o'r gwely. Yn ystod y pandemig, cymerodd Sally ei holl ofal a'i godi, er gwaethaf cael dau lawdriniaeth ar ei asgwrn cefn ei hun. Mae hi bellach yn dibynnu ar forffin i reoli poen sy'n parhau i effeithio ar ei lles cyffredinol. | |

| “ | Aeth fy nghefn yn llwyr felly mae'n rhaid i mi gymryd morffin ddwywaith y dydd i allu codi o'r gwely. Dydy fy nghefn ddim wedi gwella o'r holl godi a'r rhedeg i fyny ac i lawr a chario'r siopa a helpu mam a dad. Mae'n debyg fy mod i ar forffin am oes ac mae hynny'n cael effaith enfawr arna i, ar fy lles.” |

| Dywedodd Sally wrthym sut yr effeithiodd y straen a deimlai yn ystod y pandemig ar ei harferion bwyta, gan arwain at amrywiadau yn ei phwysau. | |

| “ | Aeth fy mwyta’n wallgof, rhoddais bwysau ymlaen, yna collais bwysau, yna rhoddais bwysau yn ôl ymlaen, yna collais ef a dyna un o’r ffyrdd rwy’n ymdopi â straen ac anhapusrwydd. Rwy’n bwyta’n gysurus ac yna rwy’n rhoi’r gorau i fwyta. Dydw i ddim wedi gwella.” |

Dywedodd rhai gofalwyr di-dâl eu bod wedi colli eu ymdeimlad o hunan wrth iddynt flaenoriaethu anghenion pobl eraill o flaen eu hanghenion eu hunain ac nad oedd ganddynt fawr ddim mynediad at seibiant na chefnogaeth.

| “ | Dydy llawer o bobl ddim yn deall, pan mae'n rhaid i chi ddarparu gofal, fod hynny fel swydd amser llawn ynddo'i hun. Mae'n heriol ac mae'n draenio'n gorfforol ac yn feddyliol. Llawer o'r amser, rwy'n teimlo nad ydw i'n berson fy hun oherwydd nad ydw i'n cael y cyfle hwnnw i feddwl amdanaf fy hun a beth yw fy anghenion. Mae'n rhaid i mi ganolbwyntio ar bawb arall.”

- Gofalwr di-dâl yn byw gyda'r person y maent yn gofalu amdano, yr Alban |

Effeithiwyd hefyd ar berthnasoedd gofalwyr di-dâl ag aelodau eraill o'u teulu yn ystod y cyfnod clo. Roedd rhai perthnasoedd dan straen o dan bwysau gofalu.

| “ | Roedd e [fy mhartner] yn arfer mynd yn flin gyda fi a byddwn i'n mynd yn flin gydag e. Roedd e'n dda iawn, iawn gyda fy mam ond byddai'n bigog gyda fi, oherwydd roedden ni'n dau wedi blino'n lân, roedd e'n cael effaith arnom ni fel cwpl, yn bendant. Roedd yn llawer o straen ar y pryd.”

- Gofalwr di-dâl, Lloegr |

| “ | Cyrhaeddodd y pwynt gyda fy mhartner lle symudodd i mewn gyda'i rieni yn ystod y cyfnod clo. Y pwysau o ofalu am fy mam a phopeth arall. Roedden ni wedi cael digon.”

- Gofalwr di-dâl, Lloegr |

Disgrifiodd rhai gofalwyr di-dâl hefyd yr effaith bersonol o ofalu am sawl person, er enghraifft plant sy'n oedolion anabl neu briod a'u rhieni eu hunain, wrth wneud gwaith â thâl a chyfrifoldebau teuluol eraill.

| “ | Mae gan fy mab wyth gofalwr sy'n cylchdroi ac yn gwneud sifftiau. Daeth hynny i gyd i ben yn ystod y pandemig. Roeddwn i'n gofalu amdano, symudodd fy mam i mewn ac roeddwn i'n gofalu amdani hi, roedd hi'n hen iawn, ac mae gen i fy merch. Roeddwn i'n teimlo fel pe bai fy hun a fy mywyd cyfan yn cael ei rannu mewn tair ffordd.”

- Gofalwr di-dâl, Lloegr |

Straeon gan ofalwyr di-dâlMewn Digwyddiad Gwrando ar-lein gyda gofalwyr di-dâl gyda Carers UK, dywedodd y rhan fwyaf o'r cyfranwyr wrthym sut roeddent yn teimlo nad oeddent yn cael eu gwerthfawrogi gan weddill cymdeithas am y gefnogaeth yr oeddent yn ei darparu, y pwysau yr oeddent oddi tano a'r doll yr oedd gofalu ar wahân yn ystod y cyfnod clo yn ei gymryd arnynt. Atgyfnerthwyd hyn ymhellach gan arddangosiadau cyhoeddus o werthfawrogiad a chefnogaeth i'r gweithlu iechyd a gofal cymdeithasol nad oedd yn cynnwys gofalwyr di-dâl. |

|

| “ | Dw i'n meddwl bod yr unigedd yn wirioneddol, wirioneddol llym, doedd neb yn gofalu amdanom ni, doedd ein [archfarchnad leol] ddim yn agor yn gynnar i ofalwyr. Roedden ni wir ar ein pennau ein hunain.”

– Gofalwr di-dâl, digwyddiad gwrando |

| “ | Doedd neb yn poeni amdano ni. Neb. Rydyn ni'n cymeradwyo dros ofalwyr, ond wnaethon ni ddim cymeradwyo droson ni oedd yn ymladd y tu ôl i ddrysau caeedig.”

– Gofalwr di-dâl, digwyddiad gwrando |

| “ | Rydych chi'n teimlo'n ynysig iawn. Does neb yn ffonio i ddweud, dim hyd yn oed galwad ffôn i ddweud, sut wyt ti, gartref yn llawn amser yn gofalu am ddau berson sy'n wirioneddol sâl? Rydw i wedi blino'n llwyr, mae gen i PTSD [anhwylder straen wedi trawma], blinder tosturi, hynny i gyd o fy rôl ofalu. Does neb yn poeni, oherwydd maen nhw'n meddwl eich bod chi'n nyrs. Ac wyddoch chi, os oes rhywbeth o'i le, rydych chi'n rhy flinedig i ofyn am help. Fel mae llawer o'r bobl eraill hyn yn ei ddweud, os oes angen help arnoch chi, wyddoch chi, mae'n rhaid i chi ymladd amdano, ymladd ac ymladd ac ymladd.”

– Gofalwr di-dâl, digwyddiad gwrando |

| “ | Arferai gofalwyr allu cael gofal seibiant. Yn sydyn, yn ystod Covid, doedd dim amser i ddianc i amgylchedd lle gallech chi fod yn chi'ch hun neu gyda phobl eraill sydd â phrofiadau tebyg, neu efallai dim ond cymryd amser i ffwrdd. Felly, roeddech chi'n gofalu am bobl yn gyson 24 awr a llai amdanoch chi'ch hun. Roedd yn bryder ac yn anobaith eithafol."

– Gofalwr di-dâl, digwyddiad gwrando |

Pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth a theimladau o unigrwydd ac arwahanrwydd

Dywedodd gweithwyr gofal cartref wrthym fod y rhai yr oeddent yn gofalu amdanynt wedi dod yn bryderus ac yn bryderus yn ystod y pandemig. Daeth rhai yn emosiynol yn ôl ac fe wnaethant roi'r gorau i ymgysylltu ag eraill. Clywsom hefyd gan weithwyr gofal cartref am sut yr achosodd unigrwydd ac arwahanrwydd pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth golli archwaeth neu ddiddordeb mewn bwyd neu ddiffyg cymhelliant i goginio a bwyta ar eu pen eu hunain.

| “ | Aeth llawer ohonyn nhw'n isel eu hysbryd, wyddoch chi, yn ddagreuol iawn ac yn bryderus. Roedd un o fy merched yn ddall, mae hi wedi marw nawr yn drist. Felly, gallwch chi ddychmygu, roedd hi'n ddall ac felly roedd hi'n ddigon anodd fel yr oedd hi gyda hi. Ac yna, hynny ar ben hynny pan nad oedd ganddi gwmni fel y cyfryw ar wahân i mi fy hun, a oedd yn dibynnu ar ba ddiwrnod ac fel arfer, weithiau dim ond dwy awr, weithiau tair awr, weithiau pedair awr yn dibynnu. Ie, felly roedd hi'n ei chael hi'n anodd iawn.”

- Gweithiwr gofal cartref, Cymru |

| “ | Doedden nhw ddim eisiau bwyta, fel, fe aethon nhw oddi ar eu bwyd ac oherwydd iechyd meddwl yn amlwg fe benderfynon nhw nad oedden nhw'n mynd i fwyta.”

- Gweithiwr gofal cartref, Lloegr |

Mewn rhai achosion, ymatebodd pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth i deimladau o unigrwydd ac arwahanrwydd drwy ymosod ar eraill, gan anafu eu hunain yn anfwriadol mewn rhai achosion. Newidiodd y pandemig safbwyntiau gweithwyr gofal hefyd ar yr hyn yr oedd yn rhaid ei flaenoriaethu ac fe daeth anoddach monitro ymddygiadau a oedd angen sylw manwl a phryderon diogelu gan na allent ymweld â phobl yn bersonol. Roedd hon yn broblem benodol i rai pobl awtistig o oedran gweithio, oedolion ag anabledd dysgu a phobl hŷn â dementia.

| “ | Roedd gennym ni drigolion yn byw gyda dementia. Roedd ymddygiad mwy heriol yn dod yn amlwg. Oherwydd eu bod nhw'n rhwystredig ac ar eu pen eu hunain.”

- Gweithiwr cartref gofal, Cymru |

Myfyriodd cyfranwyr ar pa mor anodd oedd hi i rai pobl adennill annibyniaeth ar ôl i'r cyfyngiadau symud gael eu llacio a dechreuodd cymdeithas agor eto.

| “ | Roeddwn i'n arfer bod yn gerddwr da, byddwn i'n cerdded i bobman. Ac nawr mae gen i drafferth hyd yn oed mynd allan o'r drws. Felly weithiau dw i'n teimlo'n well os ydw i'n ynysu fy hun ac yn y pen draw, dydw i ddim yn mynd i unman.”

- Person ag anghenion gofal a chymorth, Lloegr |

| “ | Sylwais fod rhai ohonyn nhw'n llai tebygol o wneud pethau drostyn nhw eu hunain oherwydd eu bod nhw mor gyfarwydd â phobl yn eu gwneud drostyn nhw. Yn ystod Covid fe wnaethon nhw stopio, felly dw i'n meddwl nad oedd rhai pobl wedi mynd yn ôl eto yn amlwg oherwydd, wyddoch chi, po hynaf ydych chi, y anoddaf ydyw. Felly, doedd rhai ohonyn nhw byth yn gallu mynd yn ôl allan ar ôl meddylfryd Covid a dyna lle byddai eu bywyd wedi newid, mewn gwirionedd yn ystod Covid.”

- Gweithiwr gofal cartref, Lloegr |

Mynediad at gefnogaeth gymunedol a chysylltiadau cymdeithasol

Roedd llawer o bobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth sy'n byw ar eu pen eu hunain neu sy'n cael gofal gan deulu yn teimlo'n ddiymadferth ac yn methu â rheoli eu bywydau beunyddiol gan fod llawer o'r gwasanaethau cymorth yr oeddent yn dibynnu arnynt wedi cau yn ystod y cyfnod clo ac wedi cymryd amser hir i ailagor.

| “ | Daeth canolfannau oedolion i ben, daeth popeth i ben, doedd dim tripiau iddyn nhw mwyach, wnaethon nhw ddim dechrau mynd i'r ganolfan oedolion eto tan ymhell ar ôl i bopeth arall agor eisoes.”

– Gweithiwr gofal cartref, Gogledd Iwerddon |

Roedd rhai pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth yn mewn gofid mawr oherwydd y newid sydyn yn eu trefn arferol a'r aflonyddwch a'r golled lwyr o'u gweithgareddau arferol a chefnogaeth y gymunedDywedodd rhai gofalwyr di-dâl sy'n gofalu am oedolion ag anabledd dysgu neu bobl awtistig fod eu perthnasoedd dan straen oherwydd y newidiadau hyn, yn enwedig lle nad oedd y bobl yr oeddent yn gofalu amdanynt yn gallu deall beth oedd yn digwydd a pham. Mewn rhai achosion, roedd pobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth yn tybio mai penderfyniad eu gofalwyr oedd hwn, gan gredu eu bod yn cael eu cadw oddi wrth bobl eraill, a arweiniodd at wrthdaro a rhwystredigaeth i bawb dan sylw.

| “ | [Pan aeth hi o chwe awr y dydd gyda gofalwyr i ddim] roedd hi'n meddwl mai dim ond rhywbeth roeddwn i'n ei wneud oedd e: roeddwn i'n ei chadw hi i mewn, doeddwn i ddim yn caniatáu iddi fynd i gwrdd â'i ffrindiau. Felly, fe wnaethon ni ddadlau cryn dipyn.”

– Gofalwr di-dâl sy'n byw gyda'r person y maent yn gofalu amdano, Cymru |

Cafodd y golled hon o drefn effaith niweidiol iawn. Disgrifiodd gofalwyr di-dâl bobl ag anghenion gofal a chymorth, yn enwedig pobl awtistig ac unigolion ag anabledd dysgu, gan arddangos ymddygiadau yr oeddent yn eu cael yn heriol ac yn ofidus i ddelio â nhw..

| “ | Collodd fy mhlentyn awtistig ei threfn arferol a fyddai’n arwain at gyfnodau anodd a theimlo’n llethol nad oedd hi’n cael seibiant o’r amgylchedd cartref gwenwynig. Effeithiodd ar ei chwsg a’i hymddygiadau; byddai hi’n cysgu am bedair awr y nos yn unig ac roedd hi’n ymosodol iawn tuag ataf gan mai dyna oedd ei hunig ffordd o gyfleu’r effaith.”

– Gofalwr di-dâl yn byw gyda'r person y maent yn gofalu amdano, Lloegr |

Stori Anne a TimAnne, sy'n byw yng Ngogledd Iwerddon, oedd gofalwr di-dâl ei mab Tim, 23 oed, sydd ag awtistiaeth ddi-eiriau. Cyn y pandemig roedd Tim yn byw gartref ac yn mynychu canolfan ddydd i oedolion, lle'r oedd wrth ei fodd ac yn gwneud yn dda iawn. Newidiodd hyn i gyd yn ystod y cyfnod clo. Pan na allai Tim fynd i'r ganolfan ddydd i oedolion a oedd ar gau yn ystod y cyfnod clo, tarfwyd ar ei drefn arferol ac effeithiodd hyn ar ei ymddygiad a'i lesiant. |

|

| “ | Roedd e’n tynnu arnoch chi’n gyson i wisgo ei ddillad, i wisgo ei gôt, i gael ei fag i fynd i’r ganolfan oedolion. Roedd e jyst yn canolbwyntio’n fawr ar fynd yn ôl i’r ganolfan oedolion. Dyna oedd e eisiau ei wneud.” |

| “ | Roedd e’n aros yn gyson i’r bws ddod. Roedd ganddo fag gyda ffolder ynddo fel ffolder dyddiol lle roedden nhw’n ysgrifennu pa fath o ddiwrnod oedd ganddo. Roedd hwnnw yn ei ddwylo drwy’r amser. Roeddwn i wedi sylwi bryd hynny nad oedd e’n cysgu o gwbl bryd hynny. Doedd e ddim yn cysgu. Roedd e efallai’n cael 40 munud y nos. Gweddill yr amser roedd e’n gynhyrfus iawn, yn rhedeg i fyny ac i lawr y grisiau, yn rhoi cynnig ar bob drws yn gyson.” |

| Er bod Anne wedi mynd â Tim am dro i fynd allan o'r tŷ, roedd yn dal yn gynhyrfus ac yn ymosod yn gorfforol mewn ffordd nad oedd wedi'i gwneud ers pan oedd yn blentyn ifanc. | |

| “ | Rydyn ni'n cael ein brathu. Mae'n brifo ei hun. Mae hefyd yn brathu ei hun ac yna byddai'n difrodi'r tŷ. Byddai'n cicio drysau.” |

| Effeithiodd hyn ar y teulu cyfan gan gynnwys ei frodyr a'i chwiorydd iau a oedd hefyd yn byw yn y cartref. | |

| “ | Roedd fy merch yn ceisio astudio ar gyfer ei TGAU gyda fy mab [awtistig] nad oedd yn cysgu o gwbl ac yn swnllyd iawn. Felly, roedd yn rhaid i [fy mhlant iau] gael cloeon ar gyfer drysau eu hystafelloedd gwely, felly roedd yn rhaid iddyn nhw gloi eu hunain yn eu hystafelloedd gwely yn y nos oherwydd ei fod yn gyson yn agor yr holl ddrysau, yn troi'r holl oleuadau ymlaen. Byddai'n rhedeg o amgylch y tŷ o ystafell i ystafell.” |

| Ymyrrodd y gwasanaethau cymdeithasol oherwydd pryderon ynghylch yr effaith ar y brodyr a'r chwiorydd a'r risg tân o blant yn cael eu cloi yn eu hystafelloedd gwely yn y nos. Effeithiodd straen gofalu am Tim heb gefnogaeth y teulu ehangach ar iechyd Anne a'i gallu i ymdopi hefyd. | |

| “ | Dim ond blinedig fel asgwrn. Roedd gen i bryder. Roedd gen i iselder. Roedd gen i bethau nad oeddwn i erioed wedi'u cael o'r blaen.” |

| O ganlyniad i effeithiau'r cyfyngiadau symud a chau'r ganolfan oedolion ar ymddygiad ac iechyd meddwl Tim ei hun, y straen ar Anne a'r effeithiau ar ei phlant eraill, symudwyd Tim i leoliad byw â chymorth yn ystod 2021 ac nid yw wedi bod yn gartref i dŷ ei fam ers hynny. | |