Mae rhai o'r straeon a'r themâu a gynhwysir yn y cofnod hwn yn cynnwys disgrifiadau o farwolaeth, profiadau bron â marw a niwed corfforol a seicolegol sylweddol. Gall y rhain beri gofid. Os felly, anogir darllenwyr i geisio cymorth gan gydweithwyr, ffrindiau, teulu, grwpiau cymorth neu weithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol lle bo angen. Darperir rhestr o wasanaethau cefnogol ar wefan UK Covid-19 Inquiry.

Rhagair

Dyma ail record Every Story Matters ar gyfer Ymchwiliad Covid-19 y DU.

I rai, mae pwnc brechlynnau Covid-19 yn fater llawn emosiwn. Roedd yna rai yr oeddent yn dymuno codi brechiad coronafeirws yn brif bwnc iddynt gyda'r Ymchwiliad.

Roedd y cyfraniadau’n amrywio ac, yn gryno, roeddent yn cynnwys:

- y rhai a oedd yn teimlo rhyddhad aruthrol bod brechlyn, a gynhyrchwyd ac a ddosbarthwyd yn ystod y pandemig, yn golygu y gallai bywyd ddychwelyd i 'normal' o bosibl.

- y rhai sy'n parhau i bryderu ynghylch pa mor gyflym y cafodd ei ddatblygu ac sy'n dal i fod yn ofalus, neu hyd yn oed yn amheus, ynghylch ei fanteision yn erbyn ei risgiau.

- y rhai a deimlai nad oeddent wedi cael llawer o ddewis yn ystod y pandemig ynghylch a ddylid cymryd y brechlyn ai peidio a phwysau cymdeithasol neu waith canfyddedig i geisio brechiad.

- y rhai sy'n dal i deimlo'n falch eu bod wedi dewis peidio â chymryd brechlyn tra bod eraill yn dathlu eu bod wedi dewis.

- y rhai a fynegodd y farn na fu, ac nad oedd, digon o wybodaeth am y brechlyn ac unrhyw sgil-effeithiau posibl, a gadawodd y gwagle hwn o wybodaeth le ar gyfer sïon, damcaniaethau cynllwynio a phryderon parhaus.

- y rhai sy'n credu bod cymryd y brechlyn wedi achosi anaf neu sgîl-effeithiau sylweddol iddynt, ac mae rhai ohonynt yn parhau.

- y rhai a deimlai nad oedd eu pryderon wedi cael sylw priodol gan arbenigwyr neu’r proffesiwn meddygol.

Roedd gan bobl y safbwyntiau gwahanol hyn o fewn teuluoedd a grwpiau o ffrindiau ac roedd eu profiadau o'r brechlynnau hefyd yn wahanol. Roedd hyn weithiau wedi achosi problemau perthynas gyda'r bobl agosaf atynt.

Roedd y bobl a ddewisodd rannu eu profiadau gyda ni fel arfer yn cael eu hysgogi gan deimladau cryf, rhai negyddol yn aml, ar destun brechlynnau a therapiwteg. Clywsom lai o straeon a phrofiadau gan bobl a ddywedodd eu bod wedi cymryd y brechlyn a’u bod yn hapus â’u penderfyniad, yn ôl pob tebyg oherwydd eu bod yn llai cymhellol i rannu eu straeon brechlyn.

Nid yw Mae Pob Stori o Bwys yn arolwg nac yn ymarferiad cymharol. Ni all fod yn gynrychioliadol o holl brofiad y DU, ac ni chafodd ei gynllunio i fod yn hynny chwaith. Ei werth yw clywed amrediad o brofiadau, dal y themâu a rannwyd â ni, dyfynnu storïau pobl yn eu geiriau eu hunain ac, yn hollbwysig, sicrhau bod profiadau pobl yn rhan o gofnod cyhoeddus yr Ymchwiliad.

Dylem bwysleisio, felly, nad yw'r cofnod hwn yn cynrychioli barn yr Ymchwiliad ei hun; yn hytrach mae’n adlewyrchiad o’r straeon a’r profiadau a rannwyd gyda ni ar bwnc sy’n esgor ar farn gref a rhanedig yn aml.

Tîm Mae Pob Stori o Bwys

Diolchiadau

Hoffem yn gyntaf ddiolch yn fawr i'r holl deuluoedd mewn profedigaeth, ffrindiau, anwyliaid a'r rhai y mae'r pandemig yn parhau i effeithio ar eu bywydau. Diolch am rannu eich profiadau, neu straeon eich anwyliaid, gyda'r Ymchwiliad.

Hoffai tîm Mae Pob Stori’n Bwysig hefyd fynegi ei werthfawrogiad diffuant i’r holl sefydliadau a restrir isod am ein helpu i ddal a deall profiadau llais a brechlyn aelodau o’u cymunedau. Roedd eich cymorth yn amhrisiadwy i ni gyrraedd cymaint o gymunedau â phosibl. Diolch am drefnu cyfleoedd i dîm Mae Pob Stori’n Bwysig glywed profiadau’r rhai rydych yn gweithio gyda nhw naill ai’n bersonol yn eich cymunedau, yn eich cynadleddau, neu ar-lein.

- Age UK

- Bereaved Families for Justice Cymru

- Clinically Vulnerable Families

- Covid19FamiliesUK

- Disability Action Northern Ireland

- Khidmat Centres Bradford / Young in Covid

- Mencap

- Cyngor Menywod Moslemaidd

- Cynghrair Hil Cymru

- Coleg Brenhinol y Bydwragedd

- Coleg Brenhinol y Nyrsys

- Sefydliad Cenedlaethol Brenhinol Pobl Ddall (RNIB)

- Scottish Covid Bereaved

- Grŵp Anafiadau Brechlyn yr Alban

- Self-Directed Support Scotland

- Sewing2gether All Nations (grŵp cymorth i ffoaduriaid)

- SignHealth

- UKCVFamily

I’r fforymau Galarwyr, Plant a Phobl Ifanc, Cydraddoldeb, Cymru, yr Alban a Gogledd Iwerddon, a grŵp Cynghori Long Covid, rydym yn wirioneddol werthfawrogi eich mewnwelediadau, eich cefnogaeth a’ch her ar ein gwaith. Roedd eich mewnbwn yn allweddol i'n helpu i lunio'r cofnod hwn.

Cofnod llawn

1. Rhagymadrodd

Mae'r ddogfen hon yn cyflwyno'r straeon a rennir gyda Every Story Matters yn ymwneud â brechlynnau a therapiwteg Covid-19.

Cefndir a nodau

Mae Every Story Matters yn gyfle i bobl ledled y DU rannu eu profiad o’r pandemig ag Ymchwiliad Covid-19 y DU. Mae pob stori a rennir wedi'i dadansoddi ac mae'r mewnwelediadau a gafwyd wedi'u troi'n ddogfennau thema ar gyfer modiwlau perthnasol. Cyflwynir y cofnodion hyn i'r Ymchwiliad fel tystiolaeth. Wrth wneud hynny, bydd canfyddiadau ac argymhellion yr Ymchwiliad yn cael eu llywio gan brofiadau'r rhai yr effeithiwyd arnynt gan y pandemig.

Mae’r ddogfen hon yn dwyn ynghyd yr hyn a ddywedodd cyfranwyr wrthym am eu profiadau o frechlynnau a therapiwteg Covid-19 ar gyfer Covid-19 yn ystod y pandemig.

Mae Ymchwiliad Covid-19 y DU yn ystyried gwahanol agweddau ar y pandemig a sut yr effeithiodd ar bobl. Mae hyn yn golygu y bydd rhai pynciau'n cael sylw mewn cofnodion modiwl eraill. Felly, nid yw'r holl brofiadau a rennir gyda Mae Pob Stori'n Bwysig wedi'u cynnwys yn y ddogfen hon. Er enghraifft, mae profiadau o systemau gofal iechyd y DU a’r effaith ar blant a phobl ifanc yn cael eu harchwilio mewn modiwlau eraill a byddant yn cael eu cynnwys mewn cofnodion eraill Mae Pob Stori’n Bwysig.

Sut mae pobl yn rhannu eu profiadau

Mae sawl ffordd wahanol i ni gasglu straeon pobl ar gyfer Modiwl 4. Mae hyn yn cynnwys:

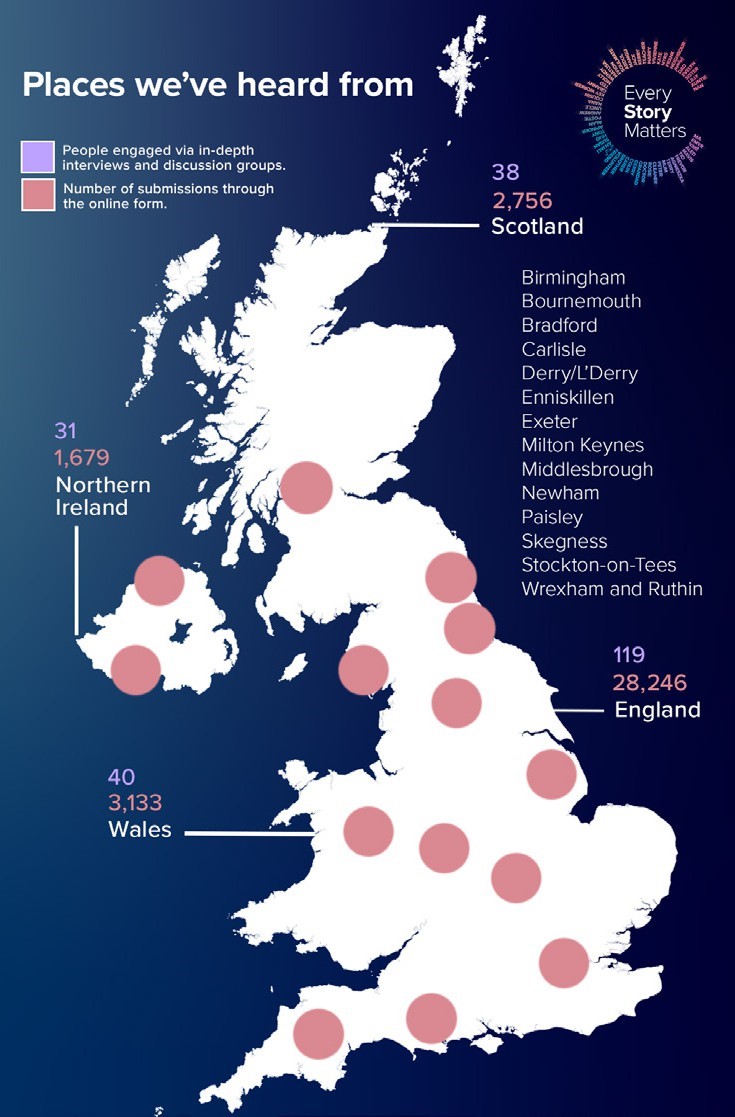

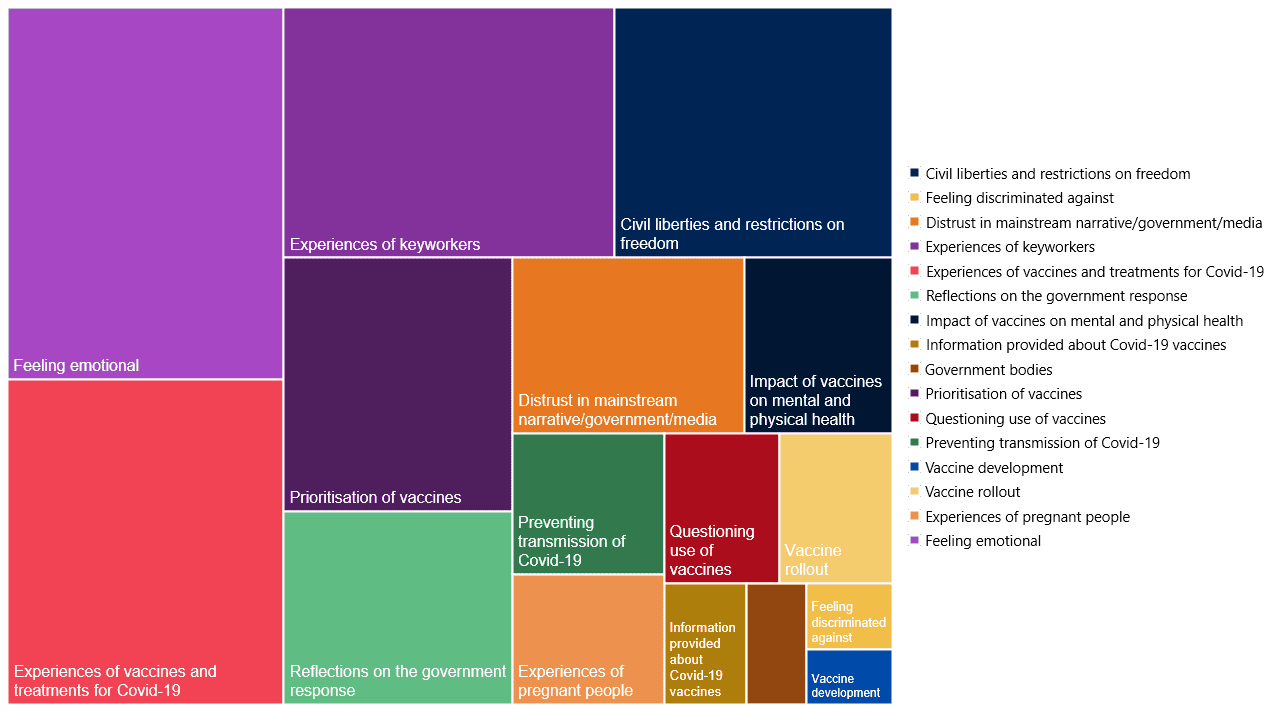

- Gwahoddwyd aelodau'r cyhoedd i gwblhau a ffurflen ar-lein drwy wefan yr Ymchwiliad (cynigiwyd ffurflenni papur hefyd i gyfranwyr a'u cynnwys yn y dadansoddiad). Gofynnodd hyn iddynt ateb tri chwestiwn eang, penagored am eu profiad pandemig. Roedd y ffurflen yn gofyn cwestiynau eraill i gasglu gwybodaeth gefndir amdanynt (fel eu hoedran, rhyw ac ethnigrwydd). Roedd hyn yn caniatáu inni glywed gan nifer fawr iawn o bobl am eu profiadau pandemig. Cyflwynwyd yr ymatebion i’r ffurflen ar-lein yn ddienw. Ar gyfer Modiwl 4, dadansoddwyd 34,441 o straeon gennym. Roedd hyn yn cynnwys 28,246 o straeon o Loegr, 2,756 o’r Alban, 3,133 o Gymru a 1,679 o Ogledd Iwerddon (roedd cyfranwyr yn gallu dewis mwy nag un wlad o’r DU ar-lein, felly bydd y cyfanswm yn uwch na nifer yr ymatebion a dderbyniwyd). Dadansoddwyd yr ymatebion trwy 'brosesu iaith naturiol' (NLP), sy'n helpu i drefnu'r data mewn ffordd ystyrlon. Trwy ddadansoddiad algorithmig, mae'r wybodaeth a gesglir yn cael ei threfnu'n 'bynciau' yn seiliedig ar dermau neu ymadroddion. Yna adolygwyd y pynciau hyn gan ymchwilwyr er mwyn archwilio'r straeon ymhellach.

- Aeth tîm Mae Pob Stori yn Bwysig i 25 o drefi a dinasoedd ar draws Cymru, Lloegr, yr Alban a Gogledd Iwerddon i roi cyfle i bobl rannu eu profiad pandemig yn bersonol yn eu cymunedau lleol. Cynhaliwyd sesiynau gwrando rhithwir hefyd, os oedd yn well gan y dull hwnnw. Buom yn gweithio gyda llawer o elusennau a grwpiau cymunedol ar lawr gwlad i siarad â’r rhai yr effeithiwyd arnynt gan y pandemig mewn ffyrdd penodol. Roedd hyn yn cynnwys teuluoedd ac unigolion mewn profedigaeth, pobl sy'n byw gyda Long Covid, teuluoedd sy'n agored i niwed yn glinigol, pobl anabl, pobl sy'n cael eu hanafu gan frechlyn, grwpiau ieuenctid, gofalwyr, ffoaduriaid, pobl o gefndiroedd lleiafrifoedd ethnig a gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol. Cafodd adroddiadau cryno byr ar gyfer digwyddiadau gyda'r grwpiau hyn eu hysgrifennu, eu rhannu â chyfranogwyr y digwyddiad a'u defnyddio i lywio'r ddogfen hon.

- Comisiynwyd consortiwm o weithwyr proffesiynol ymchwil cymdeithasol a chymunedol gan Every Story Matters i’w gynnal cyfweliadau manwl a grwpiau trafod deall profiadau grwpiau penodol, yn seiliedig ar yr hyn yr oedd tîm cyfreithiol y modiwl am ei ddeall. Roedd hyn yn cynnwys y rhai â phryderon iechyd penodol a allai fod wedi effeithio ar eu penderfyniadau brechlyn (fel y rhai a oedd yn agored i niwed yn glinigol neu’n hynod agored i niwed yn glinigol1 a'r rhai a oedd yn feichiog neu'n bwydo ar y fron pan gynigiwyd brechlyn iddynt) a grwpiau lle'r oedd nifer cymharol fach yn manteisio ar y brechlynnau Covid-19. Roedd hyn hefyd yn cynnwys aelodau o'r cyhoedd a oedd wedi cael o leiaf un brechlyn i ddeall profiadau o gyflwyno'r brechlyn. Roedd y cyfweliadau a'r grwpiau trafod hyn yn canolbwyntio ar y Prif Linellau Ymholi (KLOEs) ar gyfer Modiwl 4, y mae gwybodaeth amdanynt i'w gweld yn atodiad y ddogfen hon. Cyfrannodd cyfanswm o 228 o bobl ledled Cymru, Lloegr, yr Alban a Gogledd Iwerddon yn y modd hwn rhwng mis Hydref 2023 a mis Rhagfyr 2023. Cafodd yr holl gyfweliadau a grwpiau trafod manwl eu recordio, eu trawsgrifio, eu codio a’u dadansoddi i nodi themâu allweddol sy’n berthnasol i’r Modiwl. 4 KLOE.

Mae nifer y bobl a rannodd eu straeon ym mhob gwlad yn y DU drwy’r ffurflen ar-lein, digwyddiadau gwrando a chyfweliadau ymchwil a grwpiau trafod i’w gweld isod:

Ffigur 1: Ymgysylltiad Mae Pob Stori o Bwys ledled y DU

I gael rhagor o wybodaeth am sut y gwnaethom wrando ar bobl a’r dulliau a ddefnyddiwyd i ddadansoddi straeon, gweler yr atodiad.

Nodiadau am gyflwyniad a dehongliad straeon

Mae'n bwysig nodi nad yw'r straeon a gasglwyd trwy Every Story Matters yn gynrychioliadol o'r holl brofiadau o frechlynnau Covid-19 yn ystod y pandemig nac o farn gyhoeddus y DU. Effeithiodd y pandemig ar bawb yn y DU mewn gwahanol ffyrdd, ac er bod themâu a safbwyntiau cyffredinol yn dod i'r amlwg o'r straeon, rydym yn cydnabod pwysigrwydd profiad unigryw pawb o'r hyn a ddigwyddodd. Nod y cofnod hwn yw adlewyrchu'r gwahanol brofiadau a rannwyd gyda ni, heb geisio cysoni'r gwahanol gyfrifon.

Rydym wedi ceisio adlewyrchu’r amrywiaeth o straeon a glywsom, a all olygu bod rhai straeon a gyflwynir yma yn wahanol i’r hyn a brofodd pobl eraill, neu hyd yn oed llawer o bobl eraill yn y DU.

Archwilir rhai straeon yn fanylach trwy ddyfyniadau. Mae'r rhain wedi'u dewis i dynnu sylw at y gwahanol fathau o brofiadau y clywsom amdanynt a'r effaith a gafodd y rhain ar bobl. Mae'r dyfyniadau'n helpu i seilio'r cofnod ar yr hyn a rannodd pobl yn eu geiriau eu hunain. Mae'r cyfraniadau wedi'u gwneud yn ddienw.

Drwy gydol y cofnod, rydym yn cyfeirio at bobl a rannodd eu straeon gydag Every Story Matters fel 'cyfranwyr'. Lle bo'n briodol, rydym hefyd wedi disgrifio mwy amdanynt (er enghraifft, eu hethnigrwydd neu statws iechyd) i helpu i egluro cyd-destun a pherthnasedd eu profiad.

Casglwyd a dadansoddwyd straeon trwy gydol 2023 a 2024, sy'n golygu bod profiadau'n cael eu cofio beth amser ar ôl iddynt ddigwydd.

Strwythur y cofnod

Mae'r ddogfen hon wedi'i strwythuro i alluogi darllenwyr i ddeall sut y profodd pobl frechlynnau Covid-19.

Mae’n dechrau drwy archwilio sut y cafodd pobl brofiad o wybodaeth a dderbyniwyd am frechlynnau Covid-19 (Pennod 2) cyn symud ymlaen i drafod y ffactorau a lywiodd benderfyniadau pobl i dderbyn neu beidio â chael brechlyn (Pennod 3). Yna mae’n disgrifio profiadau o gyflwyno’r brechlyn ymhlith y rhai a ddewisodd dderbyn brechlyn (Pennod 4), cyn edrych ar effeithiau’n ymwneud ag argaeledd triniaethau (therapiwteg) ar gyfer Covid-19 ymhlith y rhai sydd mewn perygl o salwch difrifol (Pennod 5).

- Ymhlith y cyfranwyr i Mae Pob Stori’n Bwysig nid yw bob amser yn bosibl adnabod y rhai sy’n agored i niwed yn glinigol a’r rhai sy’n hynod agored i niwed yn glinigol. Mae hyn oherwydd na ddarparodd pob cyfrannwr y wybodaeth hon wrth rannu eu straeon. Lle bo’n bosibl, rydym wedi cynnwys gwybodaeth ynghylch a yw cyfranwyr yn agored i niwed yn glinigol neu’n hynod agored i niwed yn glinigol. Pan nad yw hyn yn wir, rydym yn siarad am bawb y gofynnwyd iddynt warchod yn ystod y pandemig fel cyfranwyr 'agored i niwed yn glinigol'.

2. Profiadau o negeseuon cyhoeddus am frechlynnau Covid-19 |

|

Mae’r bennod hon yn disgrifio’r hyn a ddywedodd cyfranwyr wrthym am y wybodaeth a gawsant am frechlynnau Covid-19 yn ystod y pandemig. Casglwyd barn pobl am y canllawiau swyddogol gan y llywodraeth a'r GIG. Clywsom hefyd am ffynonellau eraill o wybodaeth a ddefnyddiwyd, gan gynnwys cyfryngau traddodiadol a chymdeithasol, ffrindiau, teulu, lleoliadau ffydd a grwpiau cymunedol.

Sut y clywodd cyfranwyr gyntaf am y brechlynnau Covid-19 a'r hyn yr oeddent yn ei deimlo

Ychydig iawn o gyfranwyr a allai gofio yn union pryd y clywsant gyntaf fod brechlyn ar gyfer Covid-19 wedi'i ddatblygu. Roeddent yn aml yn adlewyrchu bod brechlynnau wedi bod yn destun sgwrs ers y cloi cyntaf yn y DU. Roedd hyn yn golygu bod brechlynnau yn rhywbeth yr oeddent wedi’i drafod yn rheolaidd gyda ffrindiau neu deulu, ac yr oeddent wedi’i weld, ei glywed, neu ei ddarllen yn y newyddion neu ar gyfryngau cymdeithasol.

| “ | Roedd yn gymaint rhan ohono - doedd dim byd arall i siarad amdano, doedd dim byd arall ar y newyddion. Nid oedd neb yn siarad am unrhyw beth ar wahân i frechiadau Covid”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Y wybodaeth gynnar fwyaf cysylltiedig am frechlynnau Covid-19 â chlywed amdanynt ar newyddion teledu. Dywedodd rhai cyfranwyr sy'n gweithio mewn lleoliadau gofal iechyd hefyd eu bod yn cael eu trafod yn eu gweithle.

| “ | Byddwn yn dweud pan welais i am y tro cyntaf, roedd ar y newyddion ... roeddwn i'n eithaf hapus am hynny, iddyn nhw fod yn cynhyrchu hwn yn gyflym i ni fel y gallem geisio mynd yn ôl i fywyd normal."

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

| “ | Clywais amdano gyntaf drwy waith, a chan ein bod yn weithiwr allweddol, cawsom ein rhoi ar lwybr carlam i allu ei gael, a dyna pryd y clywais amdano gyntaf. Dydw i ddim yn cofio’r union ddyddiadau.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Roedd clywed bod brechlyn wedi'i gymeradwyo i'w ddefnyddio yn destun amrywiaeth enfawr o emosiynau. I rai, teimladau cadarnhaol o ryddhad a gobaith oedd yn bennaf. Roedd hyn yn cynnwys llawer o’r rheini a oedd yn glinigol agored i niwed neu’n hynod agored i niwed yn glinigol, a oedd yn gofalu am ffrind neu aelod o’r teulu agored i niwed, neu a oedd yn hŷn eu hunain. Gwelwyd bod brechlyn yn cynnig y cyfle realistig cyntaf i'w bywydau ddychwelyd i normal: roedd llawer wedi bod yn gwarchod neu wedi bod yn ofalus fel arall ynghylch cymysgu â phobl ers i'r pandemig ddechrau.

| “ | Pan gadarnhawyd bod y brechlyn ar gael, y peth cyntaf a deimlais oedd, yn bersonol, daeth â gobaith i mi, oherwydd roeddwn mewn sefyllfa anobeithiol bryd hynny, a dyna pam yr oeddwn am fod yn gyntaf ar y rhestr. Roedd yn teimlo fel bod yna olau ar ddiwedd y twnnel, roedd hynny’n galonogol iawn.”

– Cyfrannwr sy’n agored i niwed yn glinigol |

| “ | Mae gen i asthma a hefyd mae gan fy nhad-yng-nghyfraith ganser, felly roedd yn ochenaid enfawr o ryddhad i bawb yn ein teulu pan glywsom am y brechlynnau.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Fodd bynnag, dywedodd eraill fod ganddynt deimladau mwy cymysg neu negyddol am y brechlynnau. Soniodd y cyfranwyr hyn am deimlo’n ofalus neu’n amheus o’r brechlynnau. Yn aml, roedd hyn yn ymwneud â phryderon ynghylch pa mor gyflym yr oedd y brechlynnau wedi'u datblygu, a oedd yn codi cwestiynau am eu diogelwch a'u heffeithiolrwydd.

| “ | Felly, i mi, nid oedd gennyf broblem gyda chael y brechlyn. Fy mhroblem i oedd, 'a oedd y brechlyn yn ddigon diogel i mi ei gael?' Pe bai wedi mynd trwy'r holl wiriadau iddo fod yn ddiogel i mi ei gael, oherwydd rwy'n gwybod bod brechlynnau'n gweithio ac maen nhw'n helpu. Felly, dyna oedd fy mhenbleth ond ar y pryd roedd y brechlyn yn cael ei gyflwyno. Roeddwn yn amheus ei fod wedi mynd drwy’r holl wiriadau moesegol a’r holl wiriadau oedd eu hangen er mwyn iddo fod yn ddiogel i mi ei gael. Felly, dyna oedd fy mhroblem i ar y dechrau.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

| “ | Rwy'n meddwl ei bod yn deg dweud bod y cyflymder y daeth allan wedi gadael ychydig o dawelwch ymhlith rhai pobl. Fe’i cyflwynwyd yn gyflym iawn, lle mae brechlynnau eraill wedi cymryd blynyddoedd i gyrraedd y farchnad. Felly yn naturiol roedd yna ychydig o ofn cyffredinol dwi’n meddwl.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Canllawiau swyddogol ar frechlynnau Covid-19

Roedd cyfranwyr yn meddwl mai’r canllawiau swyddogol ar frechlynnau Covid-19 oedd y wybodaeth a welsant ar y newyddion, mewn sesiynau briffio’r llywodraeth neu a dderbyniwyd yn uniongyrchol gan y GIG (mewn apwyntiadau gyda gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol, ar-lein, trwy ap y GIG, ac ati). Roedd llythyrau a negeseuon yn gwahodd pobl i gymryd y brechlyn hefyd yn cael eu hystyried yn wybodaeth swyddogol.

Cymysg oedd y farn am eglurder y canllawiau swyddogol ar frechlynnau Covid-19. Yn gyffredinol, teimlai cyfranwyr fod y canllawiau ar flaenoriaethu grwpiau penodol a’r broses ar gyfer cael brechlyn yn glir. Fodd bynnag, teimlai rhai fod y canllawiau ynghylch diogelwch ac effeithiolrwydd brechlynnau yn ddryslyd. Tybiodd cyfranwyr y byddai unrhyw un a dderbyniodd frechlyn yn annhebygol iawn o ddal Covid-19 (yn seiliedig ar eu profiadau o rai brechlynnau ar gyfer salwch eraill). Pan wnaethant hwy neu rywun yr oeddent yn ei adnabod a oedd wedi derbyn brechlyn gontractio Covid-19 yn ddiweddarach, cododd gwestiynau iddynt a oedd y brechlynnau'n gweithio. Ni theimlwyd bod y canllawiau swyddogol sydd ar gael ar frechlynnau Covid-19 wedi mynd i’r afael â’r dryswch hwn.

| “ | O'r hyn rwy'n ei gofio, rwy'n meddwl ei fod yn eithaf clir. Cawsoch eich llythyr, roedd y newyddion i gyd yn dweud wrthych am ei wneud. Roedd y cyngor yno yn bendant.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

| “ | Cefais y pigiad a chefais COVID o hyd. Roeddwn i'n teimlo, ar ôl i mi gael fy mhigiad, na fyddwn i'n gallu dal COVID, dyna oeddwn i'n ei feddwl, ond pam fy mod wedi cymryd y pigiad a bod gen i COVID o hyd? Felly dwi’n teimlo nad oedd y pigiad yn gweithio.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Roedd cyfranwyr hefyd yn bryderus ynghylch sut y cafodd sgîl-effeithiau andwyol posibl y brechlynnau eu cyfleu yn y canllawiau swyddogol. Roedd hyn yn arbennig o bwysig i'r rhai â chyflyrau iechyd a oedd yn bodoli eisoes a oedd am wybod sut y gallai'r brechlyn ryngweithio â'u cyflwr ac a oedd hyn yn eu rhoi mewn mwy o berygl o effeithiau andwyol.

| “ | Dylai’r holl ffeithiau fod wedi bod ar gael, gan gynnwys sgîl-effeithiau posibl y pigiadau, er mwyn gwneud penderfyniad gwybodus a rhoi caniatâd gwybodus.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

| “ | Nid oedd llawer o ymchwil i'r effaith y gallai ei chael yn feddygol ynghylch a oedd gennych gyflwr iechyd parhaus. Roeddwn ychydig yn wyliadwrus am effeithiau hirdymor y brechiad a beth allai ddigwydd.”

- Person â chyflwr iechyd hirdymor |

Nododd cyfranwyr hefyd fod yr iaith a ddefnyddiwyd a’r cysyniadau a gynhwyswyd yn y canllawiau swyddogol yn aml yn llawn jargon ac yn cynnwys iaith feddygol. Roedd hyn yn ei gwneud yn anodd i rai ddeall y canllawiau, a siaradon nhw am deimlo na allant wneud penderfyniad gwybodus o ganlyniad. Un maes penodol o ddryswch oedd y gwahanol fathau o frechlynnau sydd ar gael i'r cyhoedd.

| “ | Fyddwn i ddim yn dweud bod digon o wybodaeth roeddwn i’n ei ddeall – ond rwy’n meddwl bod digon o wybodaeth ar gael, pe bai rhywun a oedd yn ei ddeall yn gallu ei hesbonio’n well i mi, mae’n debyg y byddwn wedi ei deall bryd hynny.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

| “ | Doeddwn i ddim yn deall y gwahaniaeth rhwng y ddau frechlyn, y Pfizer un a'r llall. Yr wyf yn cofio bod un o'n cyfeillion wedi cael un, a'r llall wedi cael y llall, ac yr oeddwn fel, 'Sut y gwyddoch pa un i'w gael ?' Felly dyna beth arall roeddwn i'n teimlo nad oedden nhw'n ei esbonio mewn gwirionedd."

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Disgrifiodd rhai cyfranwyr ei bod yn ei chael yn anodd cael gwybodaeth mewn fformat sy'n hygyrch iddynt. Roedd hyn yn cynnwys y rhai â nam ar eu golwg neu'r rhai nad oedd Saesneg yn iaith gyntaf iddynt.

| “ | Rwy'n meddwl os ydych chi'n deall Saesneg, yna roedd yn iawn, ond os ydw i'n meddwl am fy nghymuned ehangach, nid yw rhai ohonyn nhw o reidrwydd yn deall Saesneg cystal â hynny, ac roedd yn anodd iddyn nhw, ac ni wnes i ddod ar draws y wybodaeth mewn fformat gwahanol…byddai’n braf pe baent wedi meddwl dod o hyd i’r cyfle i sicrhau bod y wybodaeth honno ar gael i bobl nad ydynt yn siarad Saesneg, i ddod o hyd i arweinydd cyswllt cymunedol, Imam, neu rywbeth felly.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

| “ | Helpodd fy merch ni i gael llawer o wybodaeth oddi ar y rhyngrwyd, ond roeddem yn rhwystredig nad oedd gennym wybodaeth mewn fformatau hygyrch. Roedd yna lawer o ddelweddau gweledol na all technoleg gynorthwyol eu darllen.”

- Person â cholled golwg |

| “ | Yn y dyfodol mae angen negeseuon llawer cliriach arnom, yn enwedig ar gyfer cymunedau difreintiedig. Mae pobl yn blino ar broffesiynau meddygol ymddiriedus ac mae gan gymunedau gwahanol rwystrau iaith gwahanol. Roedd yr ymdeimlad hwn o gymunedau'n cael eu difa, roedd aelodau'r teulu'n dweud 'maen nhw allan yma i'n cael ni, peidiwch â chael y brechlyn.' Ychydig iawn a wnaed i dawelu meddwl pobl yn eu hiaith eu hunain, roedd llawer o bobl ifanc yn ysgwyddo’r baich o gyfieithu hwn.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Teimlai hefyd nad oedd y canllawiau swyddogol yn mynd i'r afael â phryderon yn ymwneud â'u credoau crefyddol. Er enghraifft, siaradodd rhai cyfranwyr Mwslimaidd am ei chael yn anodd dod o hyd i wybodaeth ynghylch a oedd y brechlynnau yn halal ai peidio.

| “ | Yn llythrennol roedd yn rhaid i mi alw fy nghydweithiwr yn y GIG, oherwydd roeddwn yn gweithio i'r GIG ar y pryd. Gelwais fy nghyd-Aelod a dywedais, 'Edrychwch, rwyf eisiau gwybod beth yw cynhwysion pob un o'r brechiadau, oherwydd yn dibynnu ar beth sydd yn y cynhwysion, os oes brasterau anifeiliaid neu bethau felly, yna ni allwn ei gymryd. . Mae'n rhaid iddo fod yn addas ar gyfer llysieuwyr neu fegan.' Ac yna aethant yn ôl a dweud, 'mae hwn yn iawn. Pawb o'r ffydd honno, byddech chi'n gallu cymryd y brechiad hwnnw.' Felly, roeddwn yn unigolyn a wnaeth yr ymholiad hwnnw. Nid oedd y wybodaeth honno ar gael yn rhwydd.”

- Person o ffydd Fwslimaidd |

Fodd bynnag, roedd llawer yn cydnabod yr heriau a wynebwyd gan y llywodraeth yn ystod y pandemig. Fe wnaethant ddisgrifio'r llywodraeth fel un a oedd yn gwneud yr hyn a allai ar y pryd, yn seiliedig ar yr hyn a oedd yn hysbys am y brechlynnau.

| “ | Roedd y brechlynnau’n ymyriad a allai achub bywydau, ac, mae’n debyg, yn ystod ein hoes ni, dyma fydd un o’r uchafbwyntiau yr ydym wedi’i weld. Fe wnaethon nhw achub cannoedd o bobl, gan gynnwys fi fy hun. Rwy'n falch fy mod wedi llwyddo i gymryd y brechlyn hwn. Roedd y broses yn dda iawn. Fe wnaeth y llywodraeth gymaint ag y gallen nhw ei wneud, mae’n debyg, oherwydd does dim byd perffaith.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

| “ | Rwy'n meddwl, a dweud y gwir, clod iddynt oherwydd y ffordd y gwnaethant ei drin. Ar ddiwedd y dydd, roedd yn bandemig, roedd yna bobl yn ei chael hi'n anodd iawn, roedden ni dan glo, ac roedden nhw'n gwneud popeth o fewn eu gallu i wneud yr hyn allen nhw. Dim ond dynol ydyn nhw.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Perthnasedd canllawiau swyddogol ar gyfer pobl a oedd yn feichiog neu'n bwydo ar y fron

Ar ddechrau mis Rhagfyr 2020, y cyngor gan y Cyd-bwyllgor ar Imiwneiddio a Brechu (JCVI) oedd, oherwydd nad oedd data ar ddiogelwch brechlynnau Covid-19 yn ystod beichiogrwydd, na ddylai menywod beichiog gael cynnig brechlyn Covid-19. Ar 30 Rhagfyr 2020, y cyngor wedi’i ddiweddaru gan y JCVI oedd y gellid cynnig brechiadau i fenywod beichiog lle’r oeddent mewn perygl arbennig o uchel o ddod i gysylltiad neu gymhlethdodau difrifol oherwydd Covid-19. Ym mis Ebrill 2021, diweddarodd y JCVI ei gyngor eto, i gynghori y dylid cynnig brechlyn Covid-19 i fenywod beichiog gan nad oedd unrhyw bryderon diogelwch penodol wedi’u nodi gydag unrhyw un o’r brechlynnau Covid-19 mewn perthynas â beichiogrwydd.

Roedd natur newidiol y canllawiau swyddogol ar frechu yn ystod beichiogrwydd yn ddryslyd i lawer o’r menywod y siaradom â nhw. Roedd rhai a oedd yn feichiog yn ystod y pandemig yn cwestiynu pam fod y cyngor wedi newid gan nad oeddent yn gweld unrhyw newid yn y dystiolaeth na’r wybodaeth oedd ar gael i’w egluro. I'r rhai a oedd yn teimlo fel hyn roedd y newid yn y canllawiau wedi achosi straen a phryder ychwanegol iddynt yn ystod yr hyn a oedd eisoes yn gyfnod pryderus.

| “ | Yr wyf yn eu cofio yn dweud yn benodol, 'Ni ddylai unrhyw un sy'n feichiog neu'n ceisio beichiogi gael y brechlyn.' Roedd yna ddioddefaint cyfan drosto a chofiaf ei bod yn bwysig iawn na ddylech gael y brechlyn. Roedden ni'n ceisio cenhedlu ac yna pan es i'n feichiog yn amlwg doeddwn i ddim wedi cael y brechlyn, cadarnhawyd gan y bydwragedd na ddylwn, ni chafodd ei argymell ar y pryd. Ac yna’n sydyn hanner ffordd trwy fy meichiogrwydd, bu newid mewn amgylchiadau a chafodd pobl feichiog y brechlyn a oedd, yn fy marn i, yn rhyfedd iawn, iawn ac yn bryderus iawn.”

– Menyw a oedd yn feichiog pan gynigiwyd brechlyn iddi |

Y prif bryder ymhlith y merched y buom yn siarad â nhw oedd y gallai'r brechlyn achosi iddynt erthyliad naturiol neu niweidio eu plentyn heb ei eni. Dywedasant wrthym nad oedd y canllawiau swyddogol yn gwneud digon i fynd i’r afael â’r pryderon hyn, a waethygwyd gan yr ymdeimlad bod gweithwyr iechyd proffesiynol hyd yn oed yn ansicr pa gyngor i’w roi. I rai, arweiniodd yr ansicrwydd hwn iddynt benderfynu peidio â chymryd y brechlyn nes eu bod wedi rhoi genedigaeth.

| “ | Roeddwn i'n feichiog ar y pryd felly oherwydd eu bod wedi dweud i beidio â'i gael tra'ch bod chi'n feichiog ac yna gwnaed y penderfyniad yn gyflym iawn i ddweud y gallent, roedd hynny'n fy nychryn. Oherwydd dim ond newid yn y penderfyniad ydoedd, fel, dros nos. Felly, yn fy mhen roeddwn yn meddwl yn gyson am, 'Wel pam wnaethon nhw ddweud na yn y lle cyntaf?' Ac yna penderfynais, oherwydd roeddwn i wedi cael camesgoriad a doeddwn i ddim eisiau dim byd yn fy nghorff a allai achosi unrhyw beth i niweidio'r beichiogrwydd hwn. Felly penderfynais beidio â chael y brechlyn tra roeddwn yn feichiog. Fe wnes i ei gael ar ôl."

– Menyw a oedd yn feichiog pan gynigiwyd brechlyn iddi |

| “ | Ni allem fynd allan i'n fferyllfeydd, meddygon teulu, a bod fel, 'iawn, iawn, beth yn union yw hyn?' oherwydd nid oedd gennym yr opsiwn hwnnw mewn gwirionedd. A dydw i ddim yn meddwl bod hyd yn oed llawer o’r gweithwyr iechyd proffesiynol yn gwybod chwaith.”

– Menyw a oedd yn feichiog pan gynigiwyd brechlyn iddi |

Codwyd pryderon tebyg gan rai o’r merched y siaradom â nhw a oedd yn bwydo ar y fron pan gynigiwyd brechlyn iddynt. Soniodd y cyfranwyr hyn am boeni sut y gallai’r brechlyn effeithio ar y plentyn yr oedd yn ei fwydo ar y fron: a fyddai’n gwneud eu babi’n sâl, neu a allai roi amddiffyniad iddynt rhag Covid-19? Unwaith eto, teimlwyd nad oedd y cyngor swyddogol yn rhoi eglurder i'r rhai yn y sefyllfa hon.

| “ | Fy nghwestiwn mwyaf oedd, roeddwn i'n bwydo ar y fron, felly a yw'n mynd i effeithio ar fy mhlentyn ... a yw'n mynd i fynd i mewn i'm llaeth y fron, a yw'n mynd i effeithio ar fy mhlentyn newydd-anedig, a yw'n mynd i wneud unrhyw beth, a yw'n mynd i wneud i mi sâl?"

– Menyw a oedd yn bwydo ar y fron pan gynigiwyd brechlyn iddi |

Gwybodaeth am frechlynnau Covid-19 yn y cyfryngau

Disgrifiodd cyfranwyr weld gwahanol fathau o wybodaeth am frechlynnau Covid-19 yn y cyfryngau yn ystod y pandemig. Roedd hyn yn cynnwys gwybodaeth am ddatblygu a phrofi’r brechlynnau a diweddariadau rheolaidd ar hynt y broses gyflwyno unwaith y bydd hyn wedi dechrau.

Roedd barn gymysg ar y wybodaeth yn y cyfryngau am y brechlynnau Covid-19. Roedd rhai cyfranwyr o’r farn mai bwriad y wybodaeth oedd ar gael oedd annog pobl i’w derbyn, yn hytrach na darparu dadl gytbwys am y risgiau a’r manteision sy’n gysylltiedig â chymryd brechlyn. Arweiniodd hyn at dueddu i ddrwgdybio'r wybodaeth oedd ar gael trwy gyfryngau traddodiadol a cheisio gwybodaeth o fannau eraill.

| “ | Yr hyn a welais, efallai gan y llywodraeth, ond yn y newyddion ac ar-lein yn unig oedd, 'Ewch, mae angen ichi gael hwn, mae'n rhaid ichi gael y brechlyn hwn.' Dyna'r cyfan oedd e mewn gwirionedd, roedd fel ei fod yn cael ei orfodi arnoch chi!"

– Person a ddewisodd beidio â chael brechlyn |

| “ | Roedd y cyfryngau prif ffrwd mewn sefyllfa gref iawn, wyddoch chi, 'Wel, mae'n wych. Dyma hi', a beth ddim. Fodd bynnag, roedd straeon gwahanol bryd hynny ar YouTube. Ni wnaethoch chi erioed gael negyddol ar y cyfryngau prif ffrwd, roedd popeth yn gadarnhaol ac yn dal yn gadarnhaol. Fodd bynnag, pe baech yn ymchwilio ychydig yn ddyfnach a'ch bod am gredu'r hyn a welsoch ar y sianeli eraill hyn, nid oedd mor gadarnhaol."

– Person a ddewisodd beidio â chael brechlyn |

Fodd bynnag, roedd eraill yn gweld y diweddariadau rheolaidd a ddarperir trwy ffynonellau cyfryngau traddodiadol yn ffordd ddefnyddiol o gadw ar ben datblygiad y brechlynnau. Soniodd eraill eu bod wedi cael eu llethu gan faint o wybodaeth a thrafodaeth am frechlynnau a’r pandemig yn ehangach, a arweiniodd at ‘ddiffodd’ a cheisio ‘dianc’.

| “ | Ymhobman yr aethoch chi roedd arwyddion, pob sianel, pob allfa y gallwch chi ei ddychmygu, roedd yn ymwneud â'r brechlyn Covid-19 hwn yn unig. Doedd dim anadlu, dyna sut yr wyf yn cofio ei deimlo. Mae wedi bod yn dipyn o amser ond rwy’n cofio teimlo fy mod wedi fy mhledu â gwybodaeth Covid, a dweud y gwir roedd mor ddrwg fel fy mod yn cofio diffodd y newyddion, nid oeddwn yn gwrando mwyach oherwydd fy mod wedi cael digon.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Gwybodaeth am frechlynnau Covid-19 ar gyfryngau cymdeithasol

Roedd cyfranwyr yn cofio gweld gwybodaeth am frechlynnau Covid-19 ar draws ystod o lwyfannau cyfryngau cymdeithasol, gan gynnwys Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Twitter, Snapchat, YouTube, a WhatsApp. Yn aml, roeddent yn teimlo bod naws y wybodaeth a rennir ar gyfryngau cymdeithasol yn negyddol yn bennaf, yn enwedig wrth i'r broses gyflwyno ddechrau. Roedd cyfranwyr yn cofio nifer cynyddol o straeon am bobl a oedd wedi profi adweithiau niweidiol difrifol neu'r rhai a fu farw yn dilyn brechlyn. Dywedodd llawer fod y straeon hyn wedi arwain at awyrgylch o ofn ac amheuaeth ynghylch y brechlynnau. Yn ei dro, roeddent yn teimlo bod hyn yn caniatáu i sibrydion am y brechlynnau gyflymu.

| “ | Ar gyfryngau cymdeithasol, clywsoch straeon arswyd, ac rwy'n teimlo eich bod bob amser yn mynd i glywed y math hwnnw o beth bob amser. Rwy'n cofio bod rhywbeth am un ohonyn nhw'n cael ei gysylltu â cheuladau gwaed ar un adeg neu rywbeth. Rwy'n teimlo fel gwybod beth rydw i'n ei wneud nawr, rwy'n teimlo bod hynny'n gwbl anghymesur.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Arweiniodd y profiadau negyddol hyn at rai yn teimlo bod llawer o gamwybodaeth neu ddiffyg gwybodaeth am y brechlynnau ar-lein. Clywsom gan lawer a ddywedodd nad oeddent yn ymddiried yn yr hyn a welsant ar gyfryngau cymdeithasol. Fodd bynnag, roedd hyd yn oed rhai o'r rhai nad oeddent yn ymddiried yn y cyfryngau cymdeithasol yn meddwl y gallai'r negeseuon a welsant fod wedi dylanwadu ar eu canfyddiadau o'r brechlynnau, ac o bosibl wedi siapio eu penderfyniadau ynghylch derbyn un ai peidio.

| “ | Dwi'n gwybod nad oedd y stwff ar y cyfryngau cymdeithasol yn ddibynadwy iawn ond dwi'n meddwl oherwydd fy mod i wedi ei weld fe chwaraeodd ran enfawr yn fy mhen pan oeddwn i'n meddwl a oeddwn i eisiau cael ai peidio. [brechlyn].”

– Person a ddewisodd beidio â chael brechlyn |

Er gwaethaf y myfyrdodau hyn, roedd rhai a oedd yn teimlo bod cyfryngau cymdeithasol yn caniatáu iddynt glywed yn uniongyrchol am brofiadau negyddol o frechlynnau Covid-19 mewn ffordd nad oedd yn bosibl trwy ffynonellau eraill. Roedd y cyfranwyr hyn o'r farn bod profiadau negyddol o'r brechlynnau wedi'u tan-adrodd gan allfeydd cyfryngau traddodiadol a'r llywodraeth, ac felly'n dibynnu ar gyfryngau cymdeithasol i glywed y straeon hyn.

| “ | Rwy’n cofio mai dyna’r unig le y gwelais straeon gwir drwg, ar gyfryngau cymdeithasol, nid oedd y newyddion yn adrodd unrhyw beth drwg am y brechlynnau o’r hyn y gallaf ei gofio.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Ffynonellau eraill o wybodaeth am frechlynnau Covid-19

Roedd cyfranwyr yn aml yn ceisio gwybodaeth am frechlynnau Covid-19 o ffynonellau y tu hwnt i'r canllawiau swyddogol a'r wybodaeth sydd ar gael trwy gyfryngau traddodiadol a chymdeithasol. Roedd hyn yn cynnwys gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol, ffrindiau ac aelodau o'r teulu.

Gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol

Roedd gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol yn ffynhonnell bwysig o wybodaeth am y brechlynnau Covid-19, yn enwedig ar gyfer y rhai a oedd yn agored i niwed yn glinigol, yn hynod agored i niwed yn glinigol, yn feichiog neu'n bwydo ar y fron. Roedd y cyfranwyr hyn yn ymddiried bod cyngor meddygon, nyrsys a bydwragedd yn seiliedig ar wybodaeth feddygol o’r brechlynnau a’u risgiau a’u buddion cysylltiedig. Roeddent hefyd yn teimlo bod y cyngor a ddarparwyd wedi'i deilwra ar eu cyfer gan fod y bobl hyn yn deall eu hanes meddygol personol.

| “ | Anfonodd fy ymgynghorydd wybodaeth ataf ar gyfer fy [cyflwr iechyd]. Roedd rhai pethau wedi’u cyhoeddi’n eang i’r cyhoedd…a chefais fwy o fath o wybodaeth benodol. Fe'i torrodd i lawr ychydig ar gyfer pobl sydd wedi [cyflwr] a'r posibiliadau ohono. Cymerodd yr holl jargon i ffwrdd ychydig a gwnaeth ychydig o ganllaw idiot i'r hyn yr oedd yn ei olygu i ni.”

– Cyfrannwr sy’n agored i niwed yn glinigol |

Fodd bynnag, ni chafodd pob cyfrannwr gyngor wedi'i deilwra gan eu gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol. Disgrifiodd rhai dderbyn gwybodaeth gyfyngedig iawn am yr hyn y gallai brechlynnau Covid-19 ei olygu ar gyfer eu cyflwr(au) iechyd penodol neu feichiogrwydd.

| “ | Rwy'n cofio'n glir iawn nad oedd llawer o wybodaeth ar gael, roedd yn rhaid i mi ffonio a mynd ar ôl a cheisio cael mwy o wybodaeth. Felly dwi'n gwybod o'm rhan i, fi oedd yr un oedd yn gwneud y gwaith. Ni allech gael gweld y meddyg teulu o gwbl.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Yn fwy cyffredinol, dywedodd cyfranwyr nad oeddent yn agored i niwed yn glinigol nac yn wynebu risg uwch o Covid-19 wrthym fod y cymorth sydd ar gael gan eu darparwr gofal iechyd yn gyfyngedig. Dywedodd llawer y byddent wedi gwerthfawrogi cael gwybodaeth gan eu meddyg teulu am y brechlyn i helpu i lywio eu penderfyniad. Disgrifiodd rhai dderbyn gwybodaeth yn y canolfannau brechu, a gafodd ei groesawu ond credir ei fod wedi dod yn rhy hwyr.

| “ | Allech chi ddim cael siarad yn uniongyrchol â’r meddyg teulu amdano…efallai y byddai wedi bod yn ddefnyddiol, ond roedd mynediad cyfyngedig, nid oedd mor hygyrch.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

| “ | Rwy'n cofio mynd am fy brechlyn Covid cyntaf, cael taflen wedi'i rhoi i mi, a meddwl, 'dyma'r tro cyntaf i mi weld rhywfaint o'r wybodaeth hon, ac mewn gwirionedd nid wyf yn teimlo fy mod wedi cael amser i dreulio mewn gwirionedd. yn llawn beth mae hyn yn ei olygu, ac mae'n rhaid i mi fynd i gael fy mhigiad mewn eiliad.' Roedd y wybodaeth gywir, roedd yn teimlo fel bod honno wedi dod yn rhy hwyr. ”

– Menyw a oedd yn bwydo ar y fron pan gynigiwyd brechlyn iddi |

Cyfeillion a theulu

Soniodd llawer o’r rhai y siaradom â nhw am drafod y brechlynnau Covid-19 gyda ffrindiau a theulu. Disgrifiodd cyfranwyr sut y gwnaethant siarad ag eraill i rannu gwybodaeth, cael gwell dealltwriaeth o'r brechlyn, a siarad trwy eu proses benderfynu.

| “ | Roedd yn gymysgedd o ffrindiau, teulu, a chydweithwyr, oherwydd roedd gan bawb farn wahanol, ac roedd gan bawb straeon gwahanol. Fe glywsoch chi straeon am bobl yn marw mewn gwirionedd gyda Covid-19, felly gwnaeth hynny ichi feddwl, iawn, efallai ei bod yn dda cael y brechlyn, ac yna roedd gennych chi bobl a ddywedodd fod y brechlyn wedi lladd rhywun roedden nhw'n ei adnabod.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Roedd y rhai â theulu a ffrindiau a oedd yn weithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol yn aml yn troi atynt am gyngor. Roedd yr unigolion hyn yn teimlo'n dawel eu meddwl gan y rhai yn eu rhwydweithiau a oedd yn deall mwy am wyddoniaeth a sut mae brechlynnau'n cael eu datblygu.

| “ | Roedd yna lawer o gynllwynion, ac mae yna o hyd. Felly, yn ystod yr amser hwnnw, yn enwedig pan fyddwch chi'n ynysig, rydych chi'n cael negeseuon WhatsApp ac rydych chi'n cael dolenni i wahanol fideos o bob rhan o'r byd, ymchwilwyr fel y'u gelwir, ac ati. Weithiau doeddech chi ddim yn gwybod beth i'w gredu . Felly, os oes gennych chi rywun sy'n gweithio yn y maes hwnnw mewn gwirionedd, sy'n gweld pethau â'u llygaid eu hunain ac yn gallu dweud eu profiad wrthych chi, yna roedd hynny'n rhywbeth yr oeddech chi'n dibynnu arno hefyd.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Clywsom hefyd enghreifftiau o bobl yn trafod y brechlyn gyda’r rhai mewn amgylchiadau tebyg, gan gynnwys bod yn feichiog neu’n bwydo ar y fron neu’n agored i niwed yn glinigol.

| “ | Tra roeddwn i'n feichiog ac yn bwydo ar y fron, roedd gen i nifer o ffrindiau agos a oedd yn yr un sefyllfa, felly fe wnaethon ni siarad yn eithaf helaeth amdano. Roedd hynny'n gefnogaeth braf mewn gwirionedd. Yn absenoldeb llawer o wybodaeth ac yn absenoldeb gallu eistedd wyneb yn wyneb â rhywun yr ydych yn ei adnabod, roedd yn braf gallu cael y sgyrsiau hynny. Dim ond i gael trafodaeth gyda rhywun oedd yn teimlo felly oherwydd eu bod yn yr un cwch.”

– Menyw a oedd yn bwydo ar y fron pan gynigiwyd brechlyn iddi |

| “ | Rydw i ar grŵp Facebook gyda phobl gyda [cyflwr iechyd] felly roedd cryn dipyn o drafod yno oherwydd bod llawer ohonom ar y rhestr fregus.”

– Cyfrannwr sy’n agored i niwed yn glinigol |

Teimlai rhai nad oedd eu trafodaethau gyda ffrindiau neu deulu yn gwneud fawr ddim i'w helpu i benderfynu a ddylid derbyn brechlyn. Soniodd y cyfranwyr hyn am densiynau rhwng unigolion a chenedlaethau gwahanol, a phwysau gan aelodau’r teulu o blaid ac yn erbyn y brechlynnau.

| “ | Ie yn fy nheulu, y genhedlaeth hŷn, fe wnes i ddarganfod eu bod yn edrych arnoch chi fel rhywun hunanol os nad oeddech chi ei eisiau.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

| “ | Cefais bwysau gan fy nhad, mae'n ddyn addysgedig iawn. Ef yw'r person rydw i bob amser wedi mynd ato i gael cyngor ac arweiniad ar bopeth, o gyllid i iechyd i bob math. Ac roedd hynny'n bwysau gwirioneddol oherwydd dywedodd, 'Ni ddylech gael hyn, oherwydd mae sôn ei fod yn effeithio ar ffrwythlondeb ac rydych am gael mwy o blant.' Felly, fe wnaethom ei drafod, ond nid oedd o reidrwydd yn helpu. Yn fwy na hynny, ychwanegodd at yr ofn. ”

– Menyw a oedd yn bwydo ar y fron pan gynigiwyd brechlyn iddi |

Roedd y rhai â chredoau crefyddol weithiau'n disgrifio clywed am y brechlynnau trwy eu cymuned ffydd. Roedd rhai yn ymddiried yn y wybodaeth hon dros yr hyn a rennir gan ffynonellau eraill.

| “ | Rwy'n Dystion Jehofa, ac mae ein cymdeithas fyd-eang yn gwybod llawer am y broses o gyflwyno brechlynnau. Fe wnaethant lawer o ymchwil a rhoi gwybod i ni, fel sefydliad, y wybodaeth am y brechlyn. ”

– Tystion Jehofa |

| “ | Yn sicr roedd rhai pryderon o safbwynt Mwslemaidd. Ni allaf gofio yn onest beth oeddent. Ond rwy’n cofio bod y Cyngor Mwslimaidd, rwy’n meddwl eu bod wedi cyhoeddi rhywbeth i ddweud ‘mewn gwirionedd mae angen i chi gymryd pa gamau bynnag sy’n angenrheidiol i ymestyn bywyd, ac mae yn eich dwylo chi ac felly mae’n rhaid i chi fod yn rhagweithiol yn hyn o beth’.”

- Person o ffydd Fwslimaidd |

| “ | Roedd llawer o wybodaeth yn dod o wahanol leoedd. Doeddwn i ddim wir yn ymddiried yn unrhyw beth a oedd yn y cyfryngau, ond fy nghymuned ffydd, roedd diweddariadau gan fy nghymuned ffydd ynghylch y brechlyn. Roeddent wedi gwneud llawer o ymchwil iddo. Ac roeddwn i'n ymddiried yn hynny. ”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Ymchwil personol

Dywedodd rhai o’r rhai y siaradom â nhw eu bod wedi gwneud eu hymchwil eu hunain am y brechlynnau er mwyn llywio eu penderfyniad i dderbyn un ai peidio. Clywsom enghreifftiau o gyfranwyr yn ymgynghori ag amrywiaeth o ffynonellau, gan gynnwys cyfnodolion gwyddonol fel The Lancet a’r British Medical Journal, astudiaethau meddygol a data o’r treialon clinigol ar gyfer brechlynnau Covid-19, blogiau a thudalennau cyfryngau cymdeithasol, erthyglau newyddion, ac eraill. chwiliadau rhyngrwyd.

| “ | Roeddwn i’n gwneud cryn dipyn o fy ymchwil fy hun, felly roeddwn i’n chwilio am wybodaeth, roeddwn i’n mynd i gwmnïau, pa rai oedd yn gweithio arno, ac roeddwn i’n darllen popeth amdano.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

3. Penderfynu a ddylid cymryd brechlyn Covid-19 ai peidio |

|

Mae'r bennod hon yn archwilio'r ffactorau a lywiodd benderfyniadau cyfranwyr ynghylch a ddylid derbyn brechlyn Covid-19 ai peidio. Mae’n rhannu’r hyn a ddywedasant wrthym am sut y daethant i’w penderfyniadau, gan gynnwys profiadau’r rhai a ddewisodd gael brechlyn, a’r rhai na wnaeth.

Penderfynu a ddylid derbyn brechlyn Covid-19 ai peidio

Dywedodd llawer o gyfranwyr wrthym fod eu penderfyniad i gael brechlyn Covid-19 ai peidio yn gymharol syml. Dywedodd y cyfranwyr hyn eu bod wedi gwneud eu penderfyniad yn eithaf cyflym.

| “ | Doeddwn i ddim wir erioed wedi ystyried peidio â'i gael. Felly ie. Roedd gen i’r meddylfryd bob amser, pan gafodd ei gynnig i mi, pan oeddwn i’n gallu ei gymryd, y byddwn i’n mynd i’w gael.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

| “ | Nid wyf erioed wedi cael brechlyn pan oedd brechiad yn cael ei gynnig. Neu yn cael ei ystyried yn rhywbeth a fyddai'n fuddiol i mi ac i'm lles. Ond, wyddoch chi, dwi'n meddwl o'r cychwyn cyntaf, yn llythrennol pan ddechreuais i feddwl am, 'Oedd hwn yn rhywbeth roeddwn i eisiau?' Roeddwn i'n bendant ac yn bendant, naddo, wnes i ddim... dwi'n meddwl mai dim ond un o'r rheini oedd e, rydych chi'n clywed rhywbeth, a'ch ymateb cynhenid ar unwaith yw, 'Ydw, rydw i eisiau gwneud hynny', 'Na wnaf' t’ a fy ymateb cynhenid oedd ‘Dydw i ddim eisiau hynny.”

– Person a ddewisodd beidio â chael brechlyn |

Fodd bynnag, clywsom hefyd gan gyfranwyr a oedd yn gweld eu penderfyniad yn anodd. Disgrifiodd y cyfranwyr hyn sut yr oeddent yn aml yn symud yn ôl ac ymlaen rhwng gwahanol safleoedd, gan bwyso a mesur ffactorau cystadleuol lluosog cyn dod i'w penderfyniad terfynol. Roedd hyn yn wir ar gyfer y rhai a ddewisodd dderbyn brechlyn Covid-19 a'r rhai na ddewisodd.

| “ | Roedd cymaint o bobl yn marw o [COVID-19] ac yna dyma'r datblygiad arloesol hwn o, 'Oes, mae gennym ni frechlyn,' a oedd yn wych yn fy marn i. Ond yna dim ond pethau bach wedyn y meddyliais, 'Iawn, sut maen nhw wedi'i gael mor gyflym, ac a oedd treialon ar ei gyfer?' A dyna pryd y dechreuais gwestiynu pethau, dechrau meddwl yn fy mhen, 'Sut gwnaed hyn mor gyflym.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Y ffactorau a ddisgrifir isod yw'r rhai yr adroddwyd eu bod yn bwysig wrth lywio penderfyniadau am y dos cyntaf o frechlyn Covid-19. Roedd y ffactorau hyn yn aml hefyd yn bwysig wrth lywio penderfyniadau am ddosau brechlyn dilynol, er bod nifer fach wedi ystyried ffactorau eraill wrth benderfynu a ddylid derbyn dosau diweddarach o frechlyn Covid-19 ai peidio.

Pam y dewisodd cyfranwyr dderbyn brechlyn Covid-19

Dim rheswm cryf dros beidio â gwneud hynny

Clywsom gan sawl cyfrannwr a ddywedodd mai’r prif reswm dros ddewis cael brechlyn Covid-19 oedd oherwydd nad oeddent yn gweld unrhyw reswm cryf dros beidio â gwneud hynny. Disgrifiodd y cyfranwyr hyn yn aml ymddiried yng nghyngor y llywodraeth a’r GIG, gan gymryd na fyddai’r naill na’r llall yn argymell rhywbeth a oedd yn anniogel. I'r cyfranwyr hyn roedd eu penderfyniad yn gymharol syml: pan gynigiwyd brechlyn iddynt, fe'i cymerwyd.

| “ | Nid oedd byth yn croesi fy meddwl i beidio â chael y brechiad. Roeddwn bob amser wedi fy synnu’n fawr pan glywais unrhyw un yn dweud unrhyw beth negyddol amdano, ac wedi fy synnu a’m drysu.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

I amddiffyn eu hunain ac eraill rhag salwch difrifol neu farwolaeth

Dywedodd llawer o gyfranwyr wrthym mai rheswm pwysig pam y dewison nhw dderbyn brechlyn Covid-19 oedd oherwydd eu bod yn credu y byddai’n helpu i’w hamddiffyn nhw a’u hanwyliaid. Roedd y cyfranwyr hyn yn poeni beth fyddai'n digwydd pe byddent hwy neu anwyliaid yn mynd yn ddifrifol wael gyda Covid-19 ac yn gweld y brechlynnau fel y ffordd orau o amddiffyn eu hunain ac eraill rhag salwch difrifol neu farwolaeth. Roedd hyn yn aml yn bwysig i’r rheini â ffrindiau neu aelodau o’r teulu mewn grwpiau a oedd mewn perygl (fel perthnasau hŷn, babanod newydd-anedig, neu bobl ddiamddiffyn eraill) neu’r rhai a oedd yn wynebu risg uwch o salwch Covid-19 difrifol eu hunain.

| “ | “Roedd yn rhaid i mi gymryd [y brechlyn] ar gyfer perthnasau oedrannus, roeddwn i eisiau eu cadw'n ddiogel. Felly, 100% penderfynais ei gymryd.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

| “ | Roeddwn wedi ei brofi eisoes heb frechiad, ac wedi colli rhywun a oedd annwyl iawn i mi, a doedd dim ffordd y byddwn i eisiau rhoi fy mab fy hun trwy hynny. Fe wnes i beth oedd yn rhaid i mi ei wneud.”

– Person sy’n agored i niwed yn glinigol |

Gofynion y gweithle

Dywedodd cyfranwyr sy’n gweithio ym maes iechyd a gofal cymdeithasol yn ystod y pandemig yn aml fod eu penderfyniad i dderbyn brechlyn Covid-19 wedi’i lywio gan ofynion brechlyn yn y gweithle. Roedd y farn am hyn yn rhanedig: roedd rhai’n meddwl bod cymryd brechlyn yn bwysig gan eu bod yn credu y byddai’n helpu i’w hamddiffyn nhw a’r bobl yr oeddent yn gofalu amdanynt.

| “ | Roeddwn i'n gweithio mewn cartref gofal, ac roedd yn ddiogel i mi, ac roeddwn i'n ddiogel iddyn nhw hefyd. Felly dyna oedd fy mhryder, y gallaf o leiaf weithio yn fy ngweithle’n ddiogel, a byddaf yn mynd yn ôl adref, byddaf yn teimlo’n gyfforddus, ac rwy’n ddiogel.”

– Gweithiwr cartref gofal |

| “ | Do penderfynais ei gymryd. Roeddwn i’n gweithio gyda chleifion a oedd yn sâl iawn oherwydd roeddwn i wedi cael fy symud i uned lle’r oedd fy nghleifion ar wyntyllu, felly roedd yn rhaid i mi ei gael – allwn i ddim fforddio eu rhoi mewn perygl.”

- Gweithiwr rheng flaen yn ystod y pandemig |

Fodd bynnag, dadleuodd eraill na ddylai'r rhai sy'n gweithio ym maes iechyd a gofal cymdeithasol fod wedi cael eu rhoi dan bwysau i gael brechlyn oherwydd eu swydd. Roedd y cyfranwyr hyn yn aml yn tynnu sylw at ddiffyg data hirdymor ar y brechlynnau o ganlyniad iddynt gael eu datblygu o’r newydd, ac roeddent yn meddwl y dylai pobl fod yn rhydd i wneud eu penderfyniadau eu hunain ynghylch derbyn un. Clywsom hyn gan rai staff iechyd a gofal cymdeithasol ond hefyd gan gyfranwyr eraill yn myfyrio ar ofynion brechu yn y gweithle.

| “ | Roeddwn i'n teimlo dan bwysau i fod yn onest. Ni chefais lythyr na neges destun. Cefais alwad ffôn gan un o fy rheolwyr, dwi'n meddwl. Dim ond pwysau ydoedd. Nid yw'n deimlad braf i'w gael – a dydw i ddim yn meddwl y byddech chi'n gweld hynny mewn llawer o achosion pan mae'n ymwneud â'ch iechyd yn gyffredinol, oherwydd eich bod chi'n gwneud y penderfyniadau hynny ar eich pen eich hun onid ydych chi? Fel arfer nid oes gennych unrhyw un arall yn gynwysedig.”

- Gweithiwr rheng flaen yn ystod y pandemig |

| “ | Roedd bron i 1,000 o aelodau staff nad oeddent am gael eu brechu, fodd bynnag ymdriniodd y gwasanaeth â hyn drwy ddefnyddio ymddygiad gorfodol, rhoi pwysau ar staff, eu ffonio ar ddiwrnodau gorffwys, anfon e-byst ac mewn rhai achosion yn cael eu bwlio oherwydd eu bod wedi dewis peidio â gwneud hynny. rhoi rhywbeth yn eu cyrff a oedd yn dal i gael eu treialu heb unrhyw ddata diogelwch hirdymor. Roedd hwn yn ymddygiad hollol warthus a gafodd effaith andwyol ar lawer o staff. Roeddwn wedi rhoi dros 18 mlynedd o ymrwymiad, wedi gwneud fy swydd hyd eithaf fy ngallu, heb gael un gŵyn erioed, ond roeddwn yn barod i gael fy niswyddo os na fyddwn yn rhoi’r arbrawf hwn yn fy nghorff.”

- Gweithiwr rheng flaen yn ystod y pandemig |

Dod â'r cloeon i ben

Clywsom gan rai cyfranwyr a ddywedodd eu bod yn meddwl y byddai’r brechlynnau yn dod â’r cyfyngiadau cloi i ben ac yn rhoi’r cyfle i’w bywydau ddychwelyd i’r ffordd yr oeddent o’r blaen. Clywsom hyn yn aml gan y rhai a oedd yn ifanc, yn heini ac yn iach, ac nad oeddent yn gweld Covid-19 yn gymaint o risg i’w hiechyd ag y gallai fod i eraill, megis pobl sy’n agored i niwed yn glinigol.

| “ | Roeddwn i’n meddwl po gyntaf y byddai pawb yn cael eu brechu, y cynharaf y gallem ddechrau ailsefydlu gwaith a chwarae a theithio a, wyddoch chi, gweddill y cyfan.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

I lawer, roedd yr awydd i beidio â chael eich cyfyngu gan y cyfyngiadau ar deithio a chymdeithasu yn ffactor allweddol yn eu penderfyniad i dderbyn brechlyn Covid-19. Ar gyfer y grŵp hwn, daeth brechu yn fodd i ddod i ben, a gwnaethant ei dderbyn fel rhywbeth yr oedd angen iddynt ei wneud er mwyn teithio neu gymdeithasu.

| “ | Doedd dim llawer o ddewis. Dywedon nhw na allwch chi fynd i'r brifysgol, na allwch chi fynd i glybiau nos, bariau, ar wyliau. Fe wnaethon nhw dynnu popeth i chi os nad oedd gennych chi frechlyn. Roedd yn rhaid i chi ei gymryd os oeddech chi eisiau cael eich bywyd yn ôl.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Ymddiried yn y farn am ffigurau awdurdod

Fel y trafodwyd yn flaenorol, i rai cyfranwyr roedd cyngor gwyddonwyr a gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol yn chwarae rhan bwysig wrth lywio eu penderfyniad i dderbyn brechlyn Covid-19. Roedd y cyfranwyr hyn yn ymddiried yn y canllawiau a ddarparwyd gan y grwpiau hyn, y credwyd eu bod yn gwneud dyfarniadau am y brechlynnau ar sail tystiolaeth wyddonol yn hytrach na barn.

| “ | Nid wyf byth yn cofio ei henw, ond gwelais raglen ddogfen gyda’r academydd o Rydychen, yr academydd benywaidd a oedd yn allweddol ynghyd ag eraill wrth dynnu’r brechlyn hwnnw at ei gilydd, ac erbyn diwedd y rhaglen ddogfen roeddwn yn gwybod y byddwn yn ei chymryd pe bawn yn cael cynnig. mae'n. Atebodd hi bob cwestiwn.”

- Person a ddewisodd dderbyn brechlyn |

| “ | Rydych chi'n meithrin perthynas â [eich gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol] ac mae'n berthynas sy'n seiliedig ar ymddiriedaeth, ac roedd fy un i yn wirioneddol wych. Roeddent mor hyfryd ac felly roeddwn yn ymddiried yn llwyr ynddynt. Felly, do, fe wnes i wrando ... a gwnaeth wahaniaeth i mi. Cafodd effaith ar fy mhenderfyniad.”

– Person sy’n agored i niwed yn glinigol |

Roedd y rhai a oedd â gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol fel ffrindiau neu deulu yn aml yn troi atynt am gyngor ar y brechlynnau Covid-19, gyda'u hymddiriedaeth mewn gwyddoniaeth wedi'i hatgyfnerthu gan eu hymddiriedaeth yn eu hanwyliaid.

| “ | Mae fy chwaer yn ddeintydd, felly hi [wedi cael brechlyn Covid-19] a dywedodd hi 'ddigwyddodd dim byd i mi' wyddoch chi. Roedd hi'n un diwrnod, poen braich. Roedd fy mab yn fyfyriwr meddygol, […] felly roedd yn rhaid iddo wneud hynny hefyd. Felly, y bobl hyn, aelodau agos fy nheulu, oherwydd eu bod yn ei wneud a dim byd yn digwydd, roeddent yn iawn, ac roeddent yn galonogol, oherwydd eu bod yn y gwasanaeth iechyd.”

– Perthynas gweithwyr rheng flaen |

Pwysau cymdeithasol

Disgrifiodd eraill deimlad a pwysau mwy cyffredinol gan gymdeithas i gael eu brechu. I rai, roedd hyn yn eu gwthio i dderbyn brechlyn. Mynegodd y rhai a deimlai fel hyn dicter at y ffordd yr oedd gwybodaeth am frechlynnau Covid-19 wedi'i chyfleu i'r cyhoedd.

| “ | Cefais fy un cyntaf a'r un atgyfnerthu oherwydd hynny, math o bwysau allanol. Wyddoch chi, mae'n rhaid i chi wneud hyn. Mae'n rhaid i chi amddiffyn pawb. Amddiffyn y GIG. Amddiffyn eich teulu. Amddiffyn eich cydweithwyr […] felly dwi'n meddwl mod i'n teimlo dan bwysau. Roeddwn i'n teimlo dan orfodaeth i gael y brechiad. Roeddwn i’n teimlo’n ofnus o’i gael oherwydd doeddwn i ddim yn gwybod y goblygiadau go iawn a beth fyddai hynny’n ei gael i mi, ar fy merch, ac roeddwn i’n teimlo’n flin iawn am yr holl sefyllfa.”

– Menyw a oedd yn bwydo ar y fron pan gynigiwyd brechlyn iddi |

Pam roedd cyfranwyr yn betrusgar i dderbyn brechlyn, neu wedi dewis peidio â gwneud hynny

Diffyg hyder yn niogelwch brechlynnau Covid-19

Roedd pryderon diogelwch yn ffactor pwysig i lawer o’r cyfranwyr a oedd yn betrusgar i dderbyn brechlyn Covid-19 neu a ddewisodd beidio â gwneud hynny. Siaradodd y rhai a soniodd am hyn yn aml am ba mor gyflym yr oedd y brechlynnau wedi’u datblygu: cododd hyn gwestiynau ynghylch a oedd y broses ddatblygu wedi’i gwneud yn iawn.

| “ | Roedd rhyw elfen o feddwl tybed a oedd yn ddiogel, oherwydd y cyflymder y cafodd ei ddatblygu, felly dyna beth roeddwn i'n ei feddwl. Fy ymateb cychwynnol oedd, waw, mae hynny'n gyflym. Ail ymateb uniongyrchol, os yw mor gyflym â hynny, a yw'n ddiogel?"

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Roedd pryderon diogelwch yn arbennig o bwysig i’r rhai y clywsom ganddynt â chyflyrau iechyd hirdymor neu bobl o gefndiroedd lleiafrifoedd ethnig. Roedd y cyfranwyr hyn yn poeni nad oedd profion priodol wedi digwydd ar bobl fel nhw wrth geisio datblygu'r brechlynnau'n gyflym. Roeddent yn poeni y byddai hyn yn golygu eu bod mewn mwy o berygl o gael adwaith andwyol i'r brechlynnau.

| “ | Dewisais beidio â chael y brechlyn Covid […] Mae gen i glefyd awto imiwn ac nid oedd unrhyw bobl â chlefyd auto imiwn yn y treialon ar gyfer y brechlyn.”

– Person sy’n agored i niwed yn glinigol |

| “ | Roeddwn i eisiau gwybod a oedd y brechlyn wedi'i brofi ar draws demograffeg oherwydd bod brechlynnau'n beth mawr, p'un a ydyn nhw ar gyfer Covid ai peidio. Rydyn ni'n sôn am chwistrellu'r peth i mewn i chi. Mae'n faes iechyd dadleuol. Roeddwn yn poeni am y brechlyn wedi cael ei brofi ar leiafrifoedd anethnig mwyafrifol neu ychydig iawn, os o gwbl, ar leiafrifoedd ethnig wedi cael eu profi a beth oedd y canlyniadau hynny. O dan amgylchiadau arferol gallech ddod o hyd i'r wybodaeth honno'n hawdd…ond nid oedd y wybodaeth honno ar gael. Yn gywir felly, roedd yn gyffur newydd felly nid oedd llawer o brofiad ag ef, ond yn dal i fod, pa brofiad bynnag neu effeithiolrwydd y maent yn ei alw, a ddefnyddiwyd ganddynt bryd hynny, a oedd yn cynnwys nifer sylweddol o grwpiau Du a lleiafrifoedd ethnig? Neu grwpiau Du Affro-Caribïaidd neu Asiaidd, i warantu inni gael ychydig mwy o gysur ynddo?”

– Person o gefndir ethnig Du |

Yn fwy cyffredinol, roedd diffyg data hirdymor ar ddiogelwch ac effeithiolrwydd canfyddedig y brechlynnau yn bwysig i lawer o gyfranwyr a ddewisodd beidio â chael brechlyn. Fe wnaethant ddisgrifio sut roedd brechlynnau Covid-19 yn wahanol i frechlynnau eraill yr oeddent wedi'u derbyn yn flaenorol: roedd y brechlynnau hynny wedi bod o gwmpas ers blynyddoedd ac roedd tystiolaeth hirdymor ar eu diogelwch a'u heffeithiolrwydd. Nid oedd hyn yn wir am y brechlynnau Covid-19. Disgrifiodd y cyfranwyr hyn deimlo'n ddig nad aethpwyd i'r afael â'r pryderon hyn yn benodol yng nghanllawiau'r llywodraeth ar y brechlynnau.

| “ | Nid oedd gennyf unrhyw bryderon penodol, megis, 'gallai achosi hyn, gallai achosi clefyd X, Y neu Z, neu nam, neu beth bynnag, neu, wyddoch chi, anffrwythlondeb.' Wnes i ddim meddwl am unrhyw beth penodol. Roeddwn i newydd feddwl y gallai fod rhywfaint o sgil-effaith negyddol ohono, wyddoch chi, yn y tymor hir. Nid ydym yn gwybod yn iawn oherwydd ei fod mor newydd sbon.”

– Person a ddewisodd beidio â chael brechlyn |

Diffyg hyder yn effeithiolrwydd brechlynnau Covid-19

I lawer o gyfranwyr, roedd clywed y gallai'r rhai a dderbyniodd frechlyn Covid-19 ddal i gontractio Covid-19 godi cwestiynau ynghylch a oedd y brechlynnau'n gweithio ai peidio. Tybiodd y cyfranwyr hyn fod y brechlynnau Covid-19 wedi'u cynllunio i atal pobl rhag contractio Covid-19 (yn seiliedig ar eu profiadau o frechlynnau ar gyfer salwch eraill). Pan oedden nhw'n meddwl nad oedd hyn yn wir (er enghraifft pan wnaeth ffrindiau neu aelodau o'r teulu a oedd wedi derbyn brechlyn gontractio Covid-19 yn ddiweddarach) arweiniodd hyn at ymdeimlad o ddiffyg ymddiriedaeth yn y brechlynnau Covid-19 a ddylanwadodd ar eu penderfyniad i beidio â derbyn un.

| “ | Dyna oedd, math o, beth y daeth i lawr iddo. Meddyliais, 'Beth yw'r pwynt mewn mynd a chael fy mrechu pan allwn i ddal i gael Covid wedyn?'”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Nid yw'n cael ei ystyried yn angenrheidiol

Teimlai rhai cyfranwyr fod eu risg o salwch difrifol o Covid-19 yn isel ac felly yn ystyried nad oedd y brechlynnau yn berthnasol iddynt. Roedd y farn hon yn fwy cyffredin ymhlith y rhai a oedd wedi cael Covid-19 cyn iddynt gael cynnig brechlyn ac nad oeddent yn mynd yn sâl neu ddim ond wedi dioddef symptomau ysgafn. Teimlent nad oedd angen eu hamddiffyn rhag rhywbeth yr oeddent eisoes wedi'i brofi, gan fod ganddynt bellach imiwnedd naturiol, ac nid oeddent yn dioddef yn ddifrifol.

| “ | Roeddwn yn llwyr yn ei erbyn […] iechyd yn bennaf. Beth yw'r sgîl-effeithiau? Beth yw'r sgîl-effeithiau hirdymor? Ac eto, oherwydd fy mod wedi cael Covid ac nid oeddwn wedi cael unrhyw symptomau a doeddwn i ddim yn risg uchel. Roeddwn i eisoes wedi mynd drwyddo. Profais yn bositif, fodd bynnag, ni ddigwyddodd dim […] ac fe gafodd pawb yn fy nheulu. Roedd tua 18 ohonom ac roedd gennym ni i gyd Covid ar yr un pryd. Ac eto roeddem yn teimlo ei fod yn ddiangen. Dim ond annwyd gwael iawn oedd hi.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Dywedodd rhai o’r rhai y clywsom ganddynt eu bod wedi dewis peidio â chael brechlyn oherwydd eu bod yn ystyried y dylai eu system imiwnedd allu delio â’r firws yn naturiol, yn enwedig os oeddent yn cadw eu hunain yn ffit ac yn iach. Roedd yr unigolion hyn yn aml yn dilyn rheolau Covid-19 eraill (fel gwisgo masgiau wyneb) ac yn ymddiried yn y wybodaeth am y brechlyn. Fodd bynnag, nid oeddent yn meddwl bod angen iddynt gael eu brechu.

| “ | Rwy’n ifanc, rwy’n ffit ac yn iach, ac yn amlwg os byddaf yn ei gael mae’n debyg y byddaf yn gallu brwydro yn erbyn pethau.”

– Person a ddewisodd beidio â chael brechlyn |

Profiadau cyfredol a hanesyddol o wahaniaethu a hiliaeth

Rhannodd rhai cyfranwyr sut roedd profiadau diweddar o wahaniaethu a hiliaeth yn bwysig wrth lywio eu penderfyniad i beidio â derbyn brechlyn Covid-19. Roedd y profiadau hyn yn cael eu trafod yn amlach gan gyfranwyr o gefndiroedd lleiafrifoedd ethnig. Disgrifiodd cyfranwyr sut roedd profiadau blaenorol o wahaniaethu a hiliaeth wedi eu harwain i ddrwgdybio’r llywodraeth a’r system iechyd yn ehangach, a arweiniodd yn ei dro i deimlo’n ofnus ac yn anesmwyth ynghylch brechlynnau Covid-19. Roedd diffyg gwybodaeth am risgiau a sgil-effeithiau'r brechlynnau ar gyfer grwpiau lleiafrifoedd ethnig penodol yn gwaethygu eu pryderon.

| “ | Rwy'n Ddu... mae hynny'n golygu nad yw fy nghymuned yn cael ei hystyried mewn unrhyw agwedd ar fy mywyd, o fywyd fy nghymuned. Maent ar waelod y gasgen, os hyd yn oed yn y gasgen. Ac felly, ni fyddwn wedi ymddiried yn neb i fod wedi rhoi unrhyw wybodaeth benodol wirioneddol i mi am sut y byddai'n effeithio arnaf. Does dim ymddiriedaeth yno o hyd.”

– Person o gefndir ethnig Du |

| “ | Rwy'n ysgrifennu fel rhywun sy'n Ddu ac y mae Covid-19 wedi effeithio'n uniongyrchol ar ei fywyd […] gwrthododd niferoedd uchel o bobl Dduon gael y pigiad oherwydd diffyg ymddiriedaeth gynhenid yn y sefydliad meddygol.”

– Person o gefndir ethnig Du |

Roedd hiliaeth ganfyddedig mewn gwyddor feddygol hefyd yn bwysig wrth hysbysu sut roedd cyfranwyr o gefndiroedd lleiafrifoedd ethnig yn ystyried brechlynnau. Teimlai rhai cyfranwyr fod yna etifeddiaeth hanesyddol o gymunedau Du yn cael eu harbrofi, gan arwain at deimladau presennol o ddiffyg ymddiriedaeth.

| “ | Fe wnaethom ofyn cwestiynau ynghylch, fel, pa mor ddibynadwy ydyw, ar bwy y'i profwyd. Oherwydd bod y camsyniad hwn ynghylch, wyddoch chi, mae lleiafrifoedd ethnig bob amser yn cael eu defnyddio ar gyfer brechiadau ac os byddwn yn goroesi, yna mae'r gymuned Gwyn yn ddiogel a bydd y brechlyn yn cael ei roi iddynt. Ac mae hyn wedi digwydd i gymunedau Du, ac felly y fasnach gaethwasiaeth a hynny i gyd, defnyddiwyd yr holl frechiadau hynny […] Felly, roeddwn i eisiau i'r ofn hwnnw gael ei ddatrys a'i dawelu, felly cymerais ran yn yr ymgyrch honno dim ond i ddeall. Dywedais, wyddoch chi, 'Rwyf eisiau gwybod a ydym yn cael ein defnyddio fel moch cwta neu a ydym yn wirioneddol fodlon bod y brechlyn hwn yn gyfreithlon a'i fod yn gweithio a beth sydd gennych chi.'”

– Person o gefndir ethnig Asiaidd |

Diffyg ymddiriedaeth mewn awdurdod

Dywedodd rhai o’r bobl y buom yn siarad â nhw fod y naratif ynghylch y brechlyn Covid-19 fel rhywbeth yr oedd yn rhaid i bobl ei wneud yn llai tebygol o fod eisiau gwneud hynny. Disgrifiodd y grŵp hwn ddiffyg ymddiriedaeth tuag at lywodraeth yn gyffredinol, ac nid oeddent yn meddwl y dylent deimlo eu bod yn cael eu gorfodi i wneud rhywbeth nad oeddent am ei wneud.

| “ | Rwy'n 70 oed a gwrthodais unrhyw frechlynnau. Nid oes gan unrhyw lywodraeth yr hawl i geisio gorfodi neu orfodi ei dinasyddion i gael gweithdrefn arbrofol.”

– Person a ddewisodd beidio â chael brechlyn |

| “ | Meddyliais, 'Nid wyf yn cael gwybod beth y gallaf ac na allaf ei wneud ar sail a wyf wedi cael brechiad.' Oherwydd, mewn gwirionedd, yn y pen draw, fy nghorff i yw hwn, a dylwn gael yr hawl i ddewis yn rhydd a wyf yn cymryd hynny, rhywbeth yr oeddwn yn amlwg yn gallu ei wneud. Ond ni ddylwn i gael cyfyngiadau ar fy mywyd oherwydd penderfyniad rydw i wedi'i wneud am fy iechyd fy hun. Ac rwy'n meddwl pan gyrhaeddodd y pwynt hwnnw, roeddwn yn union fel, 'Yn hollol, nid wyf yn ymgysylltu â hyn.' Ac fe wnes i wir, er mawr syndod i'r rhai o'm cwmpas.”

– Person a ddewisodd beidio â chael brechlyn |

Agweddau personol tuag at feddygaeth

Siaradodd rhai cyfranwyr am fod yn ofalus ynghylch ymyriadau meddygol yn fwy cyffredinol, gan gynnwys brechiadau, a arweiniodd at ddewis peidio â derbyn brechlyn Covid-19. Penderfynodd llawer o'r unigolion hyn yn gynnar na fyddent yn cael brechlyn oherwydd nad oeddent yn hoffi 'rhoi dim byd yn eu corff'.

| “ | Nid wyf yn cymryd unrhyw feddyginiaeth heb fod ei angen mewn gwirionedd a chan wybod popeth amdano, yn sicr nid oeddwn yn mynd i beryglu fy mywyd yn cael brechlyn heb ei brofi fel rhiant sengl, ni fyddai hynny er lles fy mhlant.”

– Person a ddewisodd beidio â chael brechlyn |

Ffactorau a lywiodd benderfyniadau am ddosau dilynol o frechlynnau Covid-19

Roedd penderfyniadau pobl ynghylch dos cychwynnol brechlyn Covid-19 fel arfer yn berthnasol i'w penderfyniadau am ddosau dilynol. Fodd bynnag, siaradodd rhai am ystyried gwahanol ffactorau wrth wneud penderfyniadau ynghylch derbyn dosau pellach.

Ymhlith y grŵp hwn daeth rhai yn llai pryderus am risgiau salwch difrifol neu farwolaeth oherwydd Covid-19 wrth i amser fynd rhagddo. Efallai eu bod wedi dewis cymryd eu dos cyntaf neu ail ddos o frechlyn Covid-19 ond yna ar gyfer dosau dilynol wedi penderfynu peidio â'i dderbyn. Yn aml roedd hyn oherwydd eu bod yn teimlo nad oedd manteision brechu bellach yn drech na'r risgiau.

| “ | Rwy'n meddwl yn unig, [yn 2021] roedd yn beth eithaf brawychus. Roedd fy mabi yn dal yn fach iawn ac roeddem yn poeni pe na bai gennym ni y gallai rhywbeth drwg ddigwydd. Efallai y byddaf yn mynd yn sâl, efallai y byddaf yn mynd yn wael iawn, neu'n marw. Tra yn 2022, roeddwn i'n gwybod mwy amdano ac roeddwn i wedi cael Covid ac roeddwn i'n iawn, a meddyliais, 'a dweud y gwir, dydw i ddim yn mynd i ddilyn llwybr y brechlyn', oherwydd roeddwn i'n feichiog ar hynny. pwynt.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Disgrifiodd rhai sut y gwnaeth profiadau negyddol gyda dos cyntaf brechlyn Covid-19 lywio eu penderfyniad i beidio â derbyn dos(au) dilynol. Roedd y cyfranwyr hyn yn aml wedi profi adweithiau niweidiol mwy difrifol i'w dos cychwynnol a oedd yn eu gwneud yn betrusgar ac weithiau'n ofnus i gymryd dos arall.

| “ | Cefais ymateb difrifol i'r brechiad cyntaf a oedd yn sioc gan nad oeddwn yn gwybod fy mod yn risg sylweddol. Roedd y symptomau'n waeth na'r rhai roeddwn i wedi'u profi gyda Covid-19. Twymyn difrifol ac oerfel gyda chur pen erchyll (yn waeth na meigryn), allwn i ddim sefyll i fyny ... cefais yr ail ddos a hwb ond rwy'n gyndyn o gael mwy.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

4. Profiadau o gyflwyno'r brechlyn |

|

Mae'r bennod hon yn dod â phrofiadau o gyflwyno'r brechlyn ynghyd. Mae’n dechrau drwy ddisgrifio’r hyn a ddeallodd cyfranwyr o’r argymhellion ar gyfer cymhwysedd a blaenoriaethu brechlyn a wnaed gan y Cydbwyllgor ar Imiwneiddio a Brechu. Yna mae'n symud ymlaen i drafod profiadau o gyflwyno'r brechlyn yn benodol, gan gynnwys trefnu apwyntiadau, cael brechlyn, ac unrhyw brofiadau yn syth ar ôl gwneud hynny.

Dealltwriaeth o'r argymhellion ar gymhwysedd brechlynnau a blaenoriaethu a wnaed gan y Cydbwyllgor ar Imiwneiddio a Brechu.

Teimlai llawer fod y dull a ddefnyddiwyd i flaenoriaethu brechlynnau Covid-19 yn deg ac yn rhesymol. Roedd cyfranwyr yn aml yn adlewyrchu mai nifer gyfyngedig o frechlynnau oedd ar gael ac yn cytuno y dylai’r rhai sydd fwyaf mewn perygl o Covid-19 gael eu blaenoriaethu dros eraill.

| “ | Yn bersonol, credaf fod y ffordd y gwnaethant ei gyflwyno yn dda iawn, iawn. Rhoddwyd blaenoriaeth i’r bobl oedd ei gwir angen […] Ac ar ôl hynny, roedd y cyflwyniad yn eithaf da, fe’i gwnaed yn ôl oedran. Felly dechreuon nhw o 85 ymlaen, ac yna 80, yna 70, ac yna dilynodd y gweddill. Ond roedd hynny yn olynol yn gyflym.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

| “ | Rwy'n meddwl eu bod wedi cael hynny'n iawn, y flaenoriaeth. Roeddwn i’n meddwl ei fod yn agwedd synhwyrol, y rhan honno.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Roedd rhai cyfranwyr sy’n agored i niwed yn glinigol ac yn hynod agored i niwed yn glinigol yn cwestiynu pam nad oedd aelodau eraill o’u haelwyd yn gymwys i gael brechlyn ar yr un pryd ag yr oeddent. Dadleuodd y cyfranwyr hyn y byddai brechu cysylltiadau cartref pobl sy’n agored i niwed yn glinigol yn ffurfio ‘swigen amddiffynnol’ o’u cwmpas ac yn lleihau ymhellach eu siawns o ddal Covid-19. Roedd cyfranwyr sy’n hynod agored i niwed yn glinigol yn gwerthfawrogi’r newid yn y canllawiau ynghylch blaenoriaethu cysylltiadau cartref pobl â gwrthimiwnedd difrifol a ddaeth yn ddiweddarach yn y broses gyflwyno.

| “ | Rwy’n teimlo y byddai’r broses gyflwyno wedi gwneud mwy o synnwyr, pe bai gennych berson agored i niwed yn eich cartref, y byddai pawb yn y cartref hwnnw’n cael jabbing. Oherwydd fel arall fe allech chi ddal i fod mewn perygl o bobl yn mynd yn sâl.”

- Cyfrannwr sy'n agored i niwed yn glinigol |

Roedd rhai cyfranwyr yn poeni y gallai blaenoriaethu pobl sy'n agored i niwed yn glinigol ac yn hynod agored i niwed yn glinigol eu gwneud yn agored i risg ychwanegol. Tynnodd y cyfranwyr hyn sylw at sgîl-effeithiau posibl brechlynnau ac effeithiau hirdymor.

| “ | Rwy'n ei gael, ond hefyd, mae'n debyg y gallech ei weld o safbwynt arall, 'O iawn. Rydych chi'n brechu'r person mwyaf agored i niwed yn gyntaf ac os yw rhywbeth yn mynd i fynd o'i le, wyddoch chi, mae'n mynd i fod yn anoddach iddyn nhw ddod drosto a gwella ohono."

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Soniodd rhai cyfranwyr sy’n agored i niwed yn glinigol ac yn hynod agored i niwed yn glinigol na allant gymryd brechlyn pan gafodd ei gynnig iddynt. Roedd rhai wedi dewis talu i dderbyn Evwsheld2 fel dewis arall.

| “ | Dysgais nad yw pobl sy'n gwrthimiwnedd yn aml yn ymateb yn dda neu o gwbl i frechlynnau. Ar ôl un brechlyn doedd gen i ddim gwrthgyrff a symiau isel iawn ar ôl 2 frechlyn. Erbyn i drydydd dos cynradd gael ei ganiatáu, roedd fy ymateb gwrthgorff wedi prinhau ers amser maith ac roeddwn yn cael trydydd dos cynradd, gyda man cychwyn o sero...yn y diwedd roeddwn i'n talu am Evusheld ar y marc preifat hynod chwyddedig (a TAW yn cynnwys). pris uwch, a brynodd ychydig fisoedd o ryddid i mi ar ddiwedd ei effeithiolrwydd.”

- Cyfrannwr sy'n agored i niwed yn glinigol |

Teimlai rhai cyfranwyr y dylai eraill fod wedi cael eu cynnwys mewn grwpiau blaenoriaeth uchel i gael brechlyn. Roedd hyn yn cynnwys rhai oedd yn rhieni neu'n gweithio mewn ysgolion ac yn teimlo y byddai brechu plant wedi lleihau trosglwyddiad mewn lleoliadau addysg. Disgrifiodd eraill a oedd yn weithwyr allweddol (er enghraifft y rhai a oedd yn gweithio mewn carchardai neu archfarchnadoedd) neu a oedd yn ofalwyr di-dâl sut yr oeddent yn teimlo y dylai pobl yn eu sefyllfa fod wedi cael eu blaenoriaethu.

| “ | Roedd yn siomedig nad oedd athrawon yn cael eu hystyried yn weithwyr allweddol a bod llawer o’m staff yn jyglo gofalu am eu plant eu hunain yn ogystal â chyflwyno rhaglen lawn o ddysgu ar-lein...yn ogystal, roedd fy staff yn teimlo eu bod yn cael eu tanbrisio’n fawr pan nad oeddent yn gymwys i ddechrau am y brechlyn.”

- Athro ysgol yn ystod y pandemig |

| “ | Fel gofalwyr, pam na chawsom ein brechu ar yr un pryd â’r bobl yr ydym yn gofalu amdanynt? Roedd yn wallgof, roedd mam yn cael ei brechu, daethant i'r tŷ, roedd yn chwerthinllyd. Oni allent fod wedi gwneud i mi ar yr un pryd ac yna byddem yn gwybod ei bod yn derbyn gofal, nid oedd unrhyw feddwl cydgysylltiedig.”

- Gofalwr |

| “ | Rwy'n gweithio mewn carchar a chawsom ein gadael heb unrhyw gefnogaeth a dim mynediad i frechlynnau cynnar! Mae'n fy mlino bod rhan gyfan o'r gymdeithas newydd gael ei hanwybyddu ac roedd gen i 88 o ddynion yn adain fy ngharchar, 2-3 aelod o staff yn dibynnu ar faint o bobl oedd yn sâl ac yn gorfod rheoli carcharorion a staff rhwystredig ac ofnus. Ni wnaethom gymhwyso fel 'lleoliad gofal' er gwaethaf y ffaith bod gennym lawer o garcharorion hŷn mewn lle bach iawn ac felly roedd yn rhaid i mi ofalu am garcharorion Covid-positif heb fawr o PPE a heb gael fy brechlyn Covid fy hun. Fy oedran oedd 36 ar y pryd felly roedd yn rhaid i mi aros am amser hir i fod yn gymwys.”

- Gweithiwr carchar yn ystod y pandemig |

Profiadau o gyflwyno'r brechlyn

Cael gwahoddiad am frechlyn a threfnu apwyntiad

Disgrifiodd cyfranwyr amrywiol ffyrdd y cawsant eu gwahodd i dderbyn eu dos cyntaf o frechlyn Covid-19. Roedd llawer yn cofio bod hyn trwy lythyr neu neges destun gan y GIG. Dywedodd rhai bod eu meddyg teulu wedi cysylltu â nhw'n uniongyrchol, tra bod eraill wedi gweld gwybodaeth yn y cyfryngau neu ar-lein a oedd yn dweud bod pobl o'u hoedran nhw bellach yn gymwys i archebu lle.

Yn y rhan fwyaf o achosion, roedd y cyfathrebiad hwn yn hysbysu'r rhai oedd yn ei dderbyn y gallent nawr drefnu apwyntiad a rhoddodd fanylion iddynt sut i wneud hynny. Dywedodd rhai bod apwyntiad eisoes wedi'i drefnu ar eu cyfer.

| “ | Cefais y llythyr, rwy’n meddwl, a neges hefyd, rwy’n meddwl. Roedd yn glir iawn, roedd yn agos at ble roeddwn i'n byw a dim ond wythnos ynghynt. Ni allaf gofio yn union, ond roedd yn eithaf cyfleus, nid oedd yn broblem o gwbl.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

| “ | Rwy'n meddwl ei fod wedi gweithio'n dda. Cefais fy un i dros y ffôn, ffoniais y rhif a rhoesant opsiynau i mi ar gyfer yr amser, y dyddiad a’r lleoliad ac fe’i archebais.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Yn gyffredinol, roedd cyfranwyr yn teimlo bod y broses archebu brechlyn yn syml. Dywedodd llawer eu bod wedi archebu ar-lein trwy wefan y llywodraeth neu ap GIG. Archebodd rhai eu meddygfa yn uniongyrchol.

Fel arfer disgrifiwyd argaeledd apwyntiad fel da, gyda dim ond nifer fach o gyfranwyr yn sôn am broblemau dod o hyd i apwyntiad ar ddyddiad, amser, a lleoliad a oedd yn gweithio iddynt. Byddai'n well gan rai sy'n byw mewn ardaloedd mwy gwledig gael opsiwn i gael brechlyn yn nes at adref.

| “ | O, roedd yn farw syml ie. Fe aethoch chi ar y wefan, fe wnaethoch chi ddewis eich lleoliad, a rhoddodd dri lle i chi lle gallech chi ei gael, i mi beth bynnag.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

| “ | Doedd gennym ni ddim llawer o ddewis…dwi'n meddwl oherwydd ein bod ni mewn maestref, mae yna sawl cymuned fach gerllaw, felly roedd rhaid i bawb fynd i'r un ganolfan yma. Dim ond un ganolfan oedd yn ein hardal ni.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Disgrifiodd nifer fach o bobl y byddai'r broses archebu yn anoddach. Roedd y rhain yn cynnwys pobl â pherthnasau hŷn neu aelodau o'r teulu a oedd yn siarad Saesneg cyfyngedig, neu'r rhai â nam ar eu golwg.

| “ | I mi fy hun, roedd yn hawdd oherwydd fy mod yn gwybod sut i weithio cyfrifiadur. Ond dwi’n cofio nad oedd hi’n hawdd i fy nana a fy nhaid.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

| “ | Pobl sy'n dod o Bangladesh, sydd wedi bod yn byw yma ers tro ond sy'n dal heb lwyddo i ddysgu Saesneg cystal â hynny, maen nhw'n cael trafferth cael mynediad at dechnoleg. Mae’n rhaid iddyn nhw ddibynnu ar rywun.”

– Person o gefndir Bangladeshaidd |

| “ | Roedd y broses apwyntiad brechlyn yn gwbl anhygyrch i ddarllenwyr sgrin gan ei bod yn defnyddio map ar gyfer un broses a chalendr ar gyfer un arall.”

– Person â nam ar y golwg |

Roedd rhai eisiau gwybod pa fath o frechlyn y byddent yn ei dderbyn wrth drefnu apwyntiad. Roedd hyn fel arfer yn gysylltiedig â phryderon am y sgîl-effeithiau canfyddedig sy'n gysylltiedig â rhai brechlynnau o gymharu ag eraill. Roedd y cyfranwyr hyn yn adlewyrchu bod y wybodaeth hon wedyn ar gael ar y system archebu ar-lein ar ôl y newid yn y canllawiau ynghylch y brechlyn AstraZeneca.

| “ | Ar y diwrnod yr es i am fy mrechiad, doeddwn i ddim yn gwybod pa un roeddwn i'n mynd i'w gael, ac nid oedd unrhyw ffordd i mi ddarganfod. Gyda chymhlethdodau rhai o'r rhai eraill, a chan wybod nad oedd unrhyw wybodaeth am fwydo ar y fron a'r brechlyn, es i mewn i gael fy mrechiad gan feddwl, 'Nid wyf yn cael hwn oni bai fy mod yn gallu cael un Pfizer. Rwy'n hapus i adael y clinig hwn heb ei gael, a dyna fydd fy safiad.'

– Menyw a oedd yn bwydo ar y fron pan gynigiwyd brechlyn iddi |

Roedd rhai cyfranwyr yn defnyddio clinig galw i mewn yn hytrach na threfnu apwyntiad. I'r cyfranwyr hyn roedd hyn yn aml yn cynnig y cyfle i gael brechlyn yn gynt nag y byddent wedi'i wneud fel arall, neu cyn iddynt fod yn swyddogol gymwys. Er enghraifft, clywsom gan rai pobl iau a oedd yn awyddus i gael brechlyn yn gyflym er mwyn iddynt allu dychwelyd i deithio a chymdeithasu. Dywedodd eraill eu bod wedi defnyddio clinig galw i mewn yn rhwydd.

| “ | Rwy’n cofio pan gafodd y brechlynnau eu rhyddhau gyntaf a byddai slotiau amser ar gael a byddai pawb yn rhuthro i drefnu apwyntiad a phe bai un o’ch ffrindiau’n darganfod bod canolfan oedd â sbâr, byddent yn anfon negeseuon gan ddweud, 'Guys, archebwch. i mewn yma. Yn gyflym pen i lawr yno. Mae yna le, mae brechlyn sbâr.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

| “ | Es i i ganolfan cerdded i mewn amdani, mae'n haws yn tydi? Roeddwn yn llythrennol yn gallu ei wneud yn fy awr ginio yn y gwaith oherwydd ei fod yn yr un dref felly es i a gwneud hynny. Roeddwn i mewn ac allan mewn tua deng munud.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Yn derbyn y dos cyntaf o frechlyn Covid-19

Roedd cyfranwyr yn gyffredinol gadarnhaol am eu profiad yn derbyn dos cyntaf o frechlyn Covid-19. Disgrifiwyd canolfannau brechu fel rhai sydd wedi'u trefnu'n dda ac wedi'u cynllunio'n dda, a gwelwyd bod y staff yn gyfeillgar ac yn groesawgar. Roedd cyfranwyr yn gweld y broses yn hawdd ei deall ac i lawer roedd yn gymharol gyflym.

| “ | Roedd y system yn anhygoel. Roedd cannoedd ohonom mewn ciw ac roedd y cyfan yn drefnus ac mor effeithlon, roedd yn anghredadwy sut y gallent drefnu rhywbeth mor dda. Dyna fel y teimlai. Cawsom y brechiad a dywedwyd wrthym am eistedd am tua 15 munud cyn y gallem adael rhag ofn y byddai unrhyw sgîl-effeithiau. Ac ar ôl i ni gyrraedd adref, roedd gennym ni rif i'w ffonio pe bai rhywbeth yn mynd o'i le, ond aeth dim o'i le yn fy achos i. Roeddwn i'n berffaith iawn."

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

| “ | Pan gyrhaeddais y ganolfan roedd y cyfan wedi'i drefnu'n dda iawn ac roedd y gwirfoddolwyr a'r staff, y nyrsys, y meddygon, i gyd mor gymwynasgar a siriol a oedd yn dda iawn. Doedd dim synnwyr o doom mewn gwirionedd. Roedd hi fel, rydych chi i gyd yma ar gyfer y brechiad hwn a byddwn yn bwrw ymlaen ag ef. Ac rwy'n meddwl bod hynny'n eithaf, wel roedd yn rhyddhad i un peth gael y brechlyn. Ond roedd hefyd yn eithaf optimistaidd, dwi’n meddwl.”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

| “ | Roedd yn anhygoel sut y sefydlwyd yr holl ganolfannau brechu hynny a pha mor drefnus oeddent. Roedd yn teimlo fel pe baem ni i gyd yn gweithio gyda'n gilydd i ddod ar ben hynny.

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Roedd y defnydd o fesurau pellhau cymdeithasol yn golygu bod llawer yn dweud eu bod yn teimlo'n ddiogel pan gawsant eu brechlyn cyntaf.

| “ | Roedd popeth yn cael ei redeg yn dda iawn, roedd ganddyn nhw lwyth o wirfoddolwyr a oedd yn helpu, roedd pawb yn dda iawn o ran gofod ar wahân ac rwy'n meddwl eu bod wedi annog pawb i wisgo mwgwd, rwy'n eithaf siŵr bod pawb yn gwisgo mwgwd ar y pryd, dydw i ddim cofiwch weld unrhyw un na wnaeth. Oedd, roedd yn teimlo’n ddiogel.”

– Menyw a oedd yn feichiog pan gynigiwyd brechlyn iddi |

| “ | Sylwodd pawb ar y rheol dau fetr, roeddent yn gwisgo masgiau wyneb, roedd drysau ar agor. Roedd popeth wedi'i awyru'n dda. ”

– Cyfrannwr Mae Every Story Matters |

Disgrifiodd pobl ag anabledd weithiau eu bod yn wynebu rhwystrau i gael mynediad i ganolfannau brechu. Roedd enghreifftiau’n cynnwys canolfannau lleol nad oedd ganddynt le parcio i’r anabl na mynediad i gadeiriau olwyn, neu lle nad oedd dehonglwyr ar gael i bobl f/Byddar a diffyg ymwybyddiaeth o fyddardod gan staff. Yn yr achosion hyn, awgrymodd y rhai yr effeithiwyd arnynt y byddai wedi bod yn ddefnyddiol derbyn gwybodaeth am hygyrchedd cyfleusterau yn eu llythyr apwyntiad.

| “ | Ni allwn gael mynediad i wasanaeth brechu’r fferyllfa oherwydd fy mod yn anabl o ran symudedd ac nid yw maes parcio wedi’i warantu…roedd pob canolfan frechu sy’n hygyrch i’r anabl wedi’u harchebu’n llawn ers misoedd!”

– Cyfrannwr anabl |

| “ | Pan gyrhaeddais y ganolfan frechu roeddwn i mor baranoiaidd ynghylch bod pawb i mewn mwgwd, roedd yn rhaid i mi fynd â fy merch gyda mi, ac roedd yn rhaid iddi ddehongli oherwydd ni allem gael cyfieithwyr o gwbl. Ddylwn i ddim bod wedi bod yn defnyddio fy mhlant i ddehongli i mi mewn gwirionedd. Nid yw hynny’n briodol o gwbl.”

– Cyfrannwr byddar |