Rhagair

Dyma’r record gyntaf a gynhyrchwyd gan dîm Every Story Matters yn Ymchwiliad Covid-19 y DU. Mae’n dwyn ynghyd y profiadau a rannwyd gyda’r Ymchwiliad mewn perthynas â’i ymchwiliad i systemau gofal iechyd ac mae wedi’i gyflwyno gan y tîm i Gadeirydd yr Ymchwiliad, y Farwnes Hallett.

Fe wnaeth y Farwnes Hallett hi’n glir o’r cychwyn cyntaf ei bod hi eisiau

i glywed gan gynifer o bobl â phosibl, yn enwedig y rhai a oedd wedi dioddef caledi a cholled, fel y nodir yng Nghylch Gorchwyl yr Ymchwiliad. Felly fe wnaethon ni greu Mae Pob Stori’n Bwysig i’n helpu ni i glywed gan bobl mewn ffordd oedd yn addas iddyn nhw – yn ysgrifenedig, ar-lein neu ar bapur, mewn digwyddiad Mae Pob Stori’n Bwysig ledled y wlad, drwy gynhadledd fideo, gan ddefnyddio iaith arwyddion neu dros y ffôn. Mae straeon yn bwerus ac yn bersonol ac maen nhw'n dod ag effaith ddynol y pandemig yn fyw.

Drwy lansio Mae Pob Stori’n Bwysig, rhoddodd yr Ymchwiliad gyfle i bobl rannu eu profiad gyda ni, i gael rhywun i wrando arnynt, i gael eu profiad wedi’i recordio ac i gyfrannu at yr Ymchwiliad. Bydd ein cyfranwyr yn rhoi’r math o wybodaeth sydd ei hangen arni i’r Farwnes Hallett cyn dod i’w chasgliadau a gwneud argymhellion. Yn y ffordd honno, gallant helpu i sicrhau bod y DU wedi’i pharatoi’n well ar gyfer y pandemig nesaf a bod yr ymateb iddo yn fwy effeithiol.

Pan ddechreuon ni wrando ar bobl y DU am eu profiadau o'r pandemig, roeddem yn gwybod y byddai'r profiadau'n amrywiol. I lawer o bobl roedd effeithiau'r blynyddoedd hynny, a'r blynyddoedd ers hynny, yn bellgyrhaeddol. Mewn rhai achosion roedden nhw ac maen nhw'n hynod boenus, ac i rai bron yn rhy boenus i siarad amdanyn nhw. I lawer o bobl roedd y pandemig yn ddinistriol ac mae llawer yn dal i ddelio â'r canlyniadau boed yn brofedigaeth, cyflyrau meddygol hirdymor, neu fathau eraill o golled a chaledi. Clywsom hefyd fod rhai pobl eisiau symud ymlaen a pheidio â siarad am y pandemig mwyach. Weithiau clywsom bethau mwy cadarnhaol, lle roedd pobl wedi ffurfio cysylltiadau newydd, wedi dysgu rhywbeth neu wedi newid eu bywydau mewn rhyw ffordd er gwell.

Mae Every Story Matters wedi'i chynllunio i ddiogelu hunaniaeth pobl, osgoi aildrawmateiddio cymaint â phosibl a rhoi dewis iddynt sut i gyfrannu. Mae casglu a dadansoddi straeon fel hyn yn unigryw ar gyfer prosiect ymchwil; Nid yw Pob Stori o Bwys yn arolwg nac yn ymarferiad cymharol. Ni all fod yn gynrychioliadol o holl brofiad y DU ac ni chafodd ei gynllunio i fod, ond mae wedi ein galluogi i nodi themâu ymhlith profiadau pobl ac achosion nad ydynt yn ffitio i unrhyw grŵp penodol.

Yn y cofnod hwn rydym yn ymdrin â miloedd o brofiadau sy'n dangos effaith y pandemig ar gleifion, eu hanwyliaid, systemau a lleoliadau gofal iechyd, a gweithwyr allweddol ynddynt. Mae miloedd yn fwy o brofiadau nad ydynt yn ymddangos yn y cofnod hwn. Bydd yr holl brofiadau a rennir gyda ni yn llifo i gofnodion Mae Pob Stori o Bwys yn y dyfodol. Gan fod y cofnodion hyn wedi'u teilwra i'r gwahanol fodiwlau, rydym yn defnyddio straeon pobl lle gallant ychwanegu'r mewnwelediad mwyaf i'r meysydd dan ymchwiliad. Rydym yn parhau i annog pobl i rannu eu profiadau gyda ni, oherwydd eu straeon hwy sy'n gallu cefnogi a chryfhau argymhellion yr Ymchwiliad a helpu i leihau niwed pandemig yn y dyfodol. Gwiriwch wefan yr Ymholiad am y wybodaeth a'r amseroedd diweddaraf.

Rydym wedi cael cefnogaeth aruthrol gan unigolion, grwpiau a sefydliadau sydd wedi rhoi adborth a syniadau i ni ac wedi ein helpu i glywed gan ystod eang o bobl. Rydym yn ddiolchgar iawn iddynt ac rydym yn cydnabod llawer ohonynt ar y dudalen nesaf.

Mae Cyflawni Mae Pob Stori o Bwys wedi cyffwrdd â phawb a gymerodd ran. Dyma straeon a fydd yn aros gyda phawb sy'n eu clywed neu'n eu darllen am weddill eu hoes.

Tîm Mae Pob Stori o Bwys

Diolchiadau

Hoffai tîm Mae Pob Stori’n Bwysig fynegi ei werthfawrogiad diffuant i’r holl sefydliadau a restrir isod am ein helpu i ddal a deall llais a phrofiadau gofal iechyd aelodau o’u cymunedau. Roedd eich cymorth yn amhrisiadwy i ni gan helpu i sicrhau ein bod yn cyrraedd cymaint o gymunedau â phosibl. Diolch am drefnu cyfleoedd i dîm Mae Pob Stori’n Bwysig glywed profiadau’r rhai rydych yn gweithio gyda nhw naill ai’n bersonol yn eich cymunedau, yn eich cynadleddau, neu ar-lein.

- Cymdeithas yr Anesthetyddion

- Cymdeithas Geriatreg Prydain

- Carers UK

- Clinically Vulnerable Families

- Covid-19 mewn Profedigaeth Teuluoedd er Cyfiawnder Cymru

- Covid19 Families UK a Marie Curie

- Disability Action Northern Ireland, a’r Prosiect ONSIDE (a gefnogir gan Disability Action Northern Ireland)

- Gofalwyr Eden Carlisle

- Grŵp Cymorth Covid Enniskillen Long

- Cymdeithas y Byddar Foyle

- Healthwatch Cumbria

- Plant hir Covid

- Long Covid yr Alban

- Cefnogaeth Covid Hir

- SOS Covid hir

- Mencap

- Cyngor Menywod Moslemaidd

- Eiriolaeth Annibynnol Pobl yn Gyntaf

- PIMS-Hwb

- Cynghrair Hil Cymru

- Coleg Brenhinol y Bydwragedd

- Coleg Brenhinol y Nyrsys

- Sefydliad Cenedlaethol Brenhinol Pobl Ddall (RNIB)

- Scottish Covid Bereaved

- Sewing2gether Yr Holl Genhedloedd (mudiad cymunedol Ffoaduriaid)

- Self-Directed Support Scotland

- Cyngres yr Undebau Llafur

- UNSAIN

I’r fforymau Galarwyr, Plant a Phobl Ifanc, Cydraddoldeb, Cymru, yr Alban a Gogledd Iwerddon, a grwpiau Cynghori Long Covid, rydym yn wirioneddol werthfawrogi eich mewnwelediadau, eich cefnogaeth a’ch her ar ein gwaith. Roedd eich mewnbwn yn allweddol i'n helpu i lunio'r cofnod hwn.

Yn olaf ond nid yn lleiaf, hoffem gyfleu ein diolch o galon i’r holl deuluoedd, ffrindiau ac anwyliaid mewn profedigaeth am rannu eu profiadau gyda ni.

Trosolwg

Sut roedd straeon yn cael eu casglu a'u dadansoddi

Mae pob stori a rennir gyda'r Ymchwiliad yn cael ei dadansoddi a bydd yn cyfrannu at un neu fwy o ddogfennau thema fel hon. Cyflwynir y cofnodion hyn o Mae Pob Stori'n Bwysig i'r Ymchwiliad fel tystiolaeth. Mae hyn yn golygu y bydd canfyddiadau ac argymhellion yr Ymchwiliad yn cael eu llywio gan brofiadau'r rhai yr effeithiwyd arnynt gan y pandemig.

Rhannodd pobl eu profiadau gyda'r Ymchwiliad mewn gwahanol ffyrdd. Mae'r straeon a ddisgrifiodd brofiadau o ofal iechyd yn ystod y pandemig wedi'u dwyn ynghyd a'u dadansoddi i dynnu sylw at themâu allweddol. Mae’r dulliau a ddefnyddir i archwilio straeon sy’n berthnasol i’r modiwl hwn yn cynnwys:

- Dadansoddi 32,681 o straeon a gyflwynwyd ar-lein i'r Ymchwiliad, gan ddefnyddio cymysgedd o brosesu iaith naturiol ac ymchwilwyr yn adolygu a chatalogio'r hyn y mae pobl wedi'i rannu.

- Mae ymchwilwyr yn tynnu ynghyd themâu o 604 o gyfweliadau ymchwil gyda'r rhai a fu'n ymwneud â gofal iechyd yn ystod y pandemig mewn gwahanol ffyrdd gan gynnwys cleifion, anwyliaid a gweithwyr gofal iechyd.

- Ymchwilwyr yn tynnu ynghyd themâu o ddigwyddiadau gwrando Mae Pob Stori’n Bwysig gyda’r cyhoedd a grwpiau cymunedol mewn trefi a dinasoedd ar draws Lloegr, yr Alban, Cymru a Gogledd Iwerddon, gan gynnwys ymhlith y rhai a brofodd effeithiau pandemig penodol. Mae rhagor o wybodaeth am y sefydliadau y bu’r Ymchwiliad yn gweithio gyda nhw i drefnu’r digwyddiadau gwrando hyn wedi’i chynnwys yn yr adran gydnabyddiaeth.

Mae mwy o fanylion am sut y cafodd straeon pobl eu dwyn ynghyd a'u dadansoddi yn yr adroddiad hwn wedi'u cynnwys yn yr atodiad. Mae’r ddogfen hon yn adlewyrchu profiadau gwahanol heb geisio eu cysoni, gan ein bod yn cydnabod bod profiad pawb yn unigryw.

Drwy gydol yr adroddiad, rydym wedi cyfeirio at bobl a rannodd eu straeon ag Every Story Matters fel 'cyfranwyr'. Mae hyn oherwydd eu bod wedi chwarae rhan bwysig wrth ychwanegu at dystiolaeth yr Ymchwiliad ac at gofnod swyddogol y pandemig. Lle bo'n briodol, rydym hefyd wedi disgrifio mwy amdanynt (er enghraifft, gwahanol fathau o staff sy'n gweithio ym maes gofal iechyd) neu'r rheswm pam y bu iddynt rannu eu stori (er enghraifft fel cleifion neu anwyliaid) i helpu i egluro'r cyd-destun.

Archwilir rhai straeon yn fanylach trwy ddyfyniadau ac astudiaethau achos. Mae'r rhain wedi'u dewis i amlygu profiadau penodol a'r effaith a gawsant ar bobl. Mae'r dyfyniadau a'r astudiaethau achos yn helpu i seilio'r adroddiad ar yr hyn a rannodd pobl â'r Ymchwiliad yn eu geiriau eu hunain. Mae'r cyfraniadau wedi'u gwneud yn ddienw. Rydym wedi defnyddio ffugenwau ar gyfer astudiaethau achos sydd wedi'u tynnu o'r cyfweliadau ymchwil. Nid oes ffugenwau ar brofiadau a rennir gan ddulliau eraill.

Wrth roi llais i brofiadau’r cyhoedd, mae rhai o’r straeon a’r themâu a gynhwysir yn yr adroddiad hwn yn cynnwys disgrifiadau o farwolaeth, profiadau bron â marw, a niwed corfforol a seicolegol sylweddol. Mae gan y rhain y potensial i fod yn ofidus ac anogir darllenwyr i gymryd camau i gefnogi eu lles wrth iddynt wneud hynny. Gallai hyn olygu cymryd seibiannau, ystyried pa benodau sy’n teimlo’n fwy neu’n llai goddefadwy i’w darllen, a mynd at gydweithwyr, ffrindiau, teulu neu eraill cefnogol am help. Anogir darllenwyr sy'n profi trallod parhaus sy'n gysylltiedig â darllen yr adroddiad hwn i ymgynghori â'u darparwr gofal iechyd i drafod opsiynau ar gyfer cymorth. Rhestr o wasanaethau cefnogol yn cael eu darparu hefyd ar wefan UK Covid-19 Inquiry.

Y straeon a rannodd pobl am ofal iechyd yn ystod y pandemig

Dywedodd pobl wrthym am yr effeithiau newidiol niferus a gafodd y pandemig arnynt fel cleifion, anwyliaid a gweithwyr gofal iechyd, ac mae rhai yn dal i fyw gyda'r effeithiau hyn heddiw.

Roedd llawer o bobl yn wynebu problemau wrth gael mynediad at ofal iechyd yn ystod y pandemig, boed mewn sefyllfaoedd brys, ar gyfer cyflyrau iechyd acíwt, neu ar gyfer apwyntiadau mwy arferol.

Clywsom am y golled enbyd a brofwyd gan y rhai a oedd mewn profedigaeth yn ystod y pandemig. Clywsom am fywydau sydd wedi cael eu haflonyddu a’u difrodi gan ddal Covid-19, datblygu a byw gyda Long Covid ac oedi cyn derbyn triniaeth ar gyfer afiechydon difrifol eraill. Dywedodd pobl sy’n agored i niwed yn glinigol ac sy’n hynod agored i niwed yn glinigol wrthym am doll corfforol ac emosiynol gwarchod ac effaith barhaus Covid-19 ar eu bywydau.

Clywsom hefyd am bethau cadarnhaol a ddigwyddodd yn ystod y pandemig. Roedd gwasanaethau gofal iechyd yn parhau i gefnogi llawer o gleifion ac roedd enghreifftiau o ofal da i gleifion. Myfyriodd gweithwyr gofal iechyd ar bopeth a wnaethant i addasu sut yr oeddent yn trin ac yn gofalu am bobl a'r ffyrdd yr oeddent yn cefnogi anwyliaid cleifion mewn amgylchiadau heriol unigryw.

Newidiadau i ofal iechyd yn ystod y pandemig

Roedd yr ofn o ddal Covid-19 yn golygu bod llawer o bobl yn amharod i gael mynediad at wasanaethau gofal iechyd, yn enwedig yn gynnar yn y pandemig. Roedd yr ofnau cryfaf ynghylch mynd i'r ysbyty ond roeddent hefyd yn berthnasol i leoliadau gofal iechyd personol eraill. Roedd llawer o gleifion a'u hanwyliaid yn ofni y byddent yn cael eu gwahanu oherwydd polisïau ymweld.

| “ | A dweud y gwir, doedd neb eisiau mynd i'r ysbyty bryd hynny. Yn anffodus, doedd gen i ddim opsiwn. Roeddwn yn ambiwlansys i mewn. Roeddwn i wir yn ymladd i beidio â mynd i’r ysbyty bob tro, ond roedd yn beryglus, ac roedd angen i mi fod yno, ac roeddwn yn deall hynny.”

- Person yn yr ysbyty gyda Covid-19 |

| “ | Doeddwn i ddim eisiau i Dad fynd i'r ysbyty, doedd fy nhad ddim eisiau mynd i'r ysbyty chwaith. Roedd y ddau ohonom o'r un farn. Nid oedd eisiau mynd i'r ysbyty, roedd wrth ei fodd bod gartref, os yw'n mynd i farw, roedd am farw gartref. Roedden ni’n gwybod pe bai’n mynd i’r ysbyty, byddwn i’n ffarwelio wrth y drws a’r tebygrwydd yw na fyddwn i byth yn ei weld eto ac y byddai’n marw ar ei ben ei hun yn yr ysbyty.”

- Aelod o'r teulu mewn profedigaeth |

Roedd yr ofn o ddal Covid-19 ac ymwybyddiaeth y cyhoedd o'r pwysau ar systemau gofal iechyd yn golygu bod derbyniad eang i'r angen i ad-drefnu sut roedd gofal iechyd yn cael ei ddarparu yn ystod y pandemig. Rhannodd cyfranwyr lawer o enghreifftiau o ba mor heriol oedd y newidiadau hyn i gleifion, eu hanwyliaid a gweithwyr gofal iechyd.

Un newid pwysig oedd bod llawer mwy o wasanaethau’n cael eu darparu o bell, naill ai ar-lein neu dros y ffôn. Roedd cleifion, anwyliaid a chlinigwyr yn aml heb eu hargyhoeddi y gallai symptomau gael eu hasesu'n iawn heb ymgynghoriad wyneb yn wyneb.

| “ | Mae'n rhaid i mi anfon lluniau i grŵp WhatsApp fy meddyg. Mae gan fy meddygfa rif ffôn WhatsApp lle rydych chi'n anfon eich enw, dyddiad geni a'r ffotograffau ... nid yw'r un peth."

- Person sy'n byw gyda Long Covid |

Roedd rhywfaint o ddryswch ynghylch y canllawiau sydd ar waith yn ystod y pandemig - yn enwedig ar gyfer ymweld ag anwyliaid neu fynychu apwyntiadau gyda nhw. Clywsom hefyd nad oedd canllawiau’n cael eu cymhwyso’n gyson a’r problemau a’r rhwystredigaeth a achoswyd gan hyn.

Ar y pryd roedd canllawiau’r llywodraeth yn llawer mwy rhyddfrydol na’r rheolau y dewisodd yr ysbyty eu cymhwyso mewn gwirionedd, a oedd yn hynod rwystredig ac a gafodd effaith andwyol ar fy iechyd meddwl. Roedd ysbytai eraill yn llawer mwy parod, gyda defnydd o dosturi a synnwyr cyffredin.

I gleifion a oedd yn poeni am haint Covid-19, roedd Offer Amddiffynnol Personol (“PPE”) yn aml yn cael ei ystyried yn galonogol oherwydd y byddai’n lleihau’r risgiau yr oeddent yn eu hwynebu. I eraill, creodd PPE rwystr a oedd yn teimlo'n annaturiol neu'n frawychus, gan ychwanegu at eu pryder ynghylch bod yn sâl yn ystod y pandemig. Roedd rhai gweithwyr gofal iechyd yn cytuno bod PPE yn gosod rhwystr rhyngddynt a chleifion ac yn gwneud darparu gofal yn fwy heriol nag oedd cyn y pandemig.

Roedd ymweliadau ysbyty nad oeddent yn cael eu caniatáu neu'n cael eu cyfyngu yn rhwystredig ac yn aml yn frawychus i gleifion. Canfu anwyliaid nad oeddent yn gwybod beth oedd yn digwydd yn hynod o ofidus, yn enwedig pan oedd cleifion yn sâl iawn neu'n agosáu at ddiwedd eu hoes. Yn yr un modd, roedd llawer o weithwyr gofal iechyd yn rhannu pa mor ofidus nad oeddent yn gallu cyfathrebu yn y ffordd arferol ag anwyliaid a oedd mewn trallod.

| “ | 48 awr yn ddiweddarach, rydych chi'n eu ffonio i ddweud wrthyn nhw fod eu perthynas yn marw ac nad ydyn nhw'n eich credu chi a pham y dylen nhw? Ac mae ganddyn nhw gwestiynau na allwch chi eu hateb, ac mae gennych chi atebion nad ydyn nhw eu heisiau.”

-Meddyg ysbyty |

Problemau cyrchu gofal iechyd

Roedd pobl yn ei chael hi’n anodd cael mynediad at ofal iechyd yn ystod y pandemig, gydag effeithiau difrifol a pharhaol mewn rhai achosion. Roedd cleifion, anwyliaid a gweithwyr gofal iechyd wedi sylwi ar nifer o broblemau cyffredin:

- Rhannodd llawer o gleifion pa mor anodd oedd hi i drefnu apwyntiadau meddyg teulu, gan eu gadael heb unrhyw ffordd o gael cymorth meddygol arferol.

| “ | Nid oedd angen cau'r practisau meddygon teulu a lleihau hynny. Rwy'n meddwl y gallai llawer o bobl fod wedi cael eu gweld o hyd, pobl sydd â lympiau a thwmpathau neu sydd angen tynnu pethau. Rwy’n meddwl y gallent fod wedi delio â hynny. Rwy’n meddwl efallai y gallai hynny fod wedi achub ychydig o fywydau hefyd.”

– claf meddyg teulu |

- Cafodd gofal ysbyty nad yw'n gysylltiedig â Covid-19 ei gwtogi, gan arwain at oedi hir ar gyfer triniaeth, mewn rhai achosion ar gyfer salwch difrifol neu gyflyrau iechyd parhaus.

| “ | Mae gennyf sawl achos yn fy meddwl o bobl a oedd yn dioddef o gyflyrau anfalaen ond cyfyngol, a oedd yn hawdd iawn eu trwsio pe baent wedi cael mynediad at ofal iechyd acíwt yn gynt. Ond, wyddoch chi, roedd hi’n anodd iawn iddyn nhw gael mynediad at ofal iechyd, i weld y person roedd angen iddyn nhw ei wneud.”

-Meddyg ysbyty |

- Roedd y rhai a geisiodd gael mynediad at ofal brys weithiau’n methu â chael cymorth neu’n wynebu oedi sylweddol, hyd yn oed pan oedden nhw neu eu hanwyliaid yn sâl iawn.

| “ | Fel arfer efallai y bydd 30 galwad yn aros ar unrhyw un adeg. Ar adegau brig yn y pandemig roedd 900 o alwadau yn aros.”

– triniwr galwadau GIG 111 |

Myfyriodd cyfranwyr ar sut y cynyddodd dicter a rhwystredigaeth ynghylch cael mynediad at ofal wrth i'r pandemig fynd rhagddo. Roedd llawer ohonynt yn beio’r problemau hyn am bobl yn gorfod byw gyda phoen a symptomau eraill, gan leihau ansawdd eu bywyd ac arwain at waethygu iechyd. Roedd rhai achosion o oedi, canslo neu gamgymeriadau ar draws gofal iechyd yn ystod y pandemig yn cysylltu’n uniongyrchol â phroblemau iechyd difrifol neu farwolaeth anwylyd.

Roedd cleifion, anwyliaid a chlinigwyr yn aml yn rhwystredig bod trin Covid-19 a lleihau lledaeniad y clefyd yn cael ei flaenoriaethu dros anghenion gofal iechyd difrifol eraill. Dadleuodd llawer o gyfranwyr y gellid bod wedi gwneud mwy i osgoi’r effeithiau negyddol ar gleifion nad ydynt yn ymwneud â Covid.

Yn y cyfnod cloi, roedd pobl yn dal yn wael. Cafodd rhywun ddiagnosis o ganser ac ni allai gael apwyntiad. Peidiwch ag esgeuluso pobl ag anghenion triniaeth eraill. Cafodd y driniaeth chemo ei chanslo, datblygodd y canser, a buont farw.

Clywsom hefyd am y rhwystrau penodol niferus i gael mynediad at ofal – a derbyn gofal da – a wynebir gan bobl ag anabledd, y rhai nad ydynt yn siarad Saesneg a’r rhai heb dechnoleg ddigidol na rhyngrwyd dibynadwy.

| “ | Nid oedd deall gwybodaeth, bod yn fyddar, methu â chyfathrebu, llawer o bethau ar-lein, a gorfod defnyddio Saesneg ac ysgrifennu, wyddoch chi, e-byst a phethau felly a negeseuon testun yn hygyrch iawn i mi.”

- Person byddar |

Tynnodd rhai cyfranwyr sylw hefyd at sut y gwaethygodd y pandemig yr anghydraddoldebau presennol.

Gwelais yn uniongyrchol effaith Covid-19 ar gymuned a oedd eisoes dan anfantais oherwydd llawer o anfanteision cymdeithasol gan gynnwys tlodi. Unwaith eto, gwelais nad oes ots gan fywydau du. Rhwygwyd Covid-19 [lle roeddwn i’n byw] gan fod Covid-19 wedi cael effaith andwyol ar weithwyr rheng flaen, pobl o liw, pobl ar gontractau dim oriau na fyddent ar ffyrlo ac na allent fforddio rhoi’r gorau i weithio.

| “ | Byddwn i'n dweud fy mod i'n un o'r bobl fwyaf hyderus i ofyn cwestiynau, ond hyd yn oed fi rydw i weithiau'n teimlo ychydig o gywilydd, 'Ydw i'n gofyn gormod? Neu a all pobl ddeall yr hyn rwy'n ceisio'i egluro?' Ti'n gwybod? Roeddwn i'n adnabod rhai pobl, nid iaith yn unig oedd yn rhwystr, a dweud y gwir, y darn llythrennedd hefyd. Mae fel, dydyn nhw ddim yn gallu darllen, dydyn nhw ddim yn gallu ysgrifennu, dydyn nhw ddim yn deall yr iaith. Hyd yn oed pan wnaethoch chi ei esbonio mewn Tsieinëeg, roedd y term meddygol yn rhy gymhleth iddyn nhw. ”

- Person sy'n siarad Saesneg fel ail iaith |

Profiadau o Covid-19

Roedd rhai gweithwyr gofal iechyd yn teimlo eu bod wedi'u cymell i weithio'n uniongyrchol gyda chleifion Covid-19. Roeddent eisiau gwneud yr hyn a allent i helpu, er gwaethaf yr ofn o ddod i gysylltiad uniongyrchol â'r firws. Roedd llawer o weithwyr gofal iechyd yn poeni am ddal Covid-19 eu hunain a'i drosglwyddo i'w teuluoedd.

Bob dydd byddwn yn mynd i mewn i weld marwolaeth a bob dydd byddwn yn meddwl tybed ai dyma'r diwrnod yr wyf yn mynd ag ef adref at fy mhlant bach.

Rhannodd rhai sut y gwnaethant golli cydweithwyr i'r afiechyd.

| “ | Aeth y tri ohonom a aeth am hyfforddiant yn sâl… gyda symptomau Covid-19. Gwellodd ffrind arall a minnau (pob nyrs a pharafeddygon) ond o fewn pythefnos roedd ein ffrind arall wedi marw, a ganfuwyd gan barafeddygon gartref yn unig ar ôl galw am help oherwydd ar y pryd roedd pobl yn cael eu cynghori i beidio â theithio i'r ysbyty. Roedd hi’n 29 oed a bu farw ar ei phen ei hun.”

- Gweithiwr gofal iechyd proffesiynol |

Dywedodd gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol sy’n trin cleifion Covid-19 wrthym eu bod wedi gwneud eu gorau er gwaethaf yr heriau enfawr yr oeddent yn eu hwynebu, weithiau heb yr offer a’r adnoddau staff yr oedd eu hangen arnynt. Roedd hyn yn eu rhoi dan straen aruthrol a disgrifiodd llawer eu bod yn teimlo dan straen ac wedi blino'n lân. Dywedasant wrthym fod eu profiadau wedi cael effaith negyddol ar eu hiechyd meddwl. Er gwaethaf yr heriau, rhannodd y rhai a driniodd cleifion Covid-19 hefyd sut y gwnaeth y gofal a gynigiwyd ganddynt wella wrth i'r pandemig fynd rhagddo a dysgwyd mwy am y clefyd.

| “ | Rwy’n gwybod fy mod yn gweld llawer o drawma yn aml, ond roedd hyn… ar lefel wahanol. Roedd yn rhywbeth nad oedd yr un ohonom wedi ei brofi. Ac roedd pawb yn gwibio eu ffordd drwy’r sefyllfa hon, nad oedd neb yn gwybod sut i’w thrin, ond roedden ni’n gwneud ein gorau.”

- Parafeddyg |

Disgrifiodd llawer o gleifion Covid-19 pa mor ofnus oedd arnynt ynghylch cael eu derbyn i’r ysbyty yn annisgwyl gyda Covid-19 a pha mor ddryslyd ydoedd. Roedd rhai yn cael trafferth cofio llawer am eu hamser yn yr ysbyty oherwydd eu bod mor sâl.

Un diwrnod fe ddeffrais yn yr ICU methu symud, siarad, bwyta, yfed ac ati. Roeddwn i'n dibynnu'n llwyr ar staff i fynd i'm golchi, bwydo fi, ac ati. o dracheostomi yn fy ngwddf. Mae'n debyg, roeddwn i wedi bod mewn coma anwythol ers dau fis.

Dywedodd rhai cleifion a oedd yn yr ysbyty â Covid-19 difrifol wrthym eu bod yn dal i gael eu trawmateiddio gan eu profiadau. Clywsom pa mor annifyr oedd gweld marwolaethau cleifion Covid-19 eraill, a sut yr ychwanegodd hyn at ofnau am y clefyd.

| “ | Ychydig wythnosau wedyn, dirywiodd iechyd meddwl fy mab, roedd yn cael gweledigaethau o fod yn ôl yn ei ward ysbyty ac roedd y dyn o'r gwely drws nesaf iddo yn yr ysbyty yn sefyll yn ei ystafell ac yn grac nad oedd yn ei helpu ... fe yn crio yn Tesco oherwydd bod canu’r tiliau yn mynd ag ef yn ôl i’r monitors yn canu yn yr ysbyty.”

– Gofalwr ar gyfer claf yn yr ysbyty gyda Covid-19 |

Effaith y pandemig

Gofal diwedd oes a phrofedigaeth

Rhannodd llawer o deuluoedd, ffrindiau a chydweithwyr profedigaeth eu colled, dinistr a dicter. Yn aml, nid oeddent yn cael ymweld ac nid oedd ganddynt fawr o gysylltiad, os o gwbl, â'u hanwyliaid a oedd yn marw. Roedd yn rhaid i rai ffarwelio dros y ffôn neu ddefnyddio tabled. Roedd yn rhaid i eraill wneud hynny wrth gadw eu pellter a gwisgo PPE llawn.

Roedd gan deuluoedd a ffrindiau mewn profedigaeth lawer llai o ymwneud â phenderfyniadau am eu hanwyliaid nag y byddent fel arfer. Clywsom am anwyliaid yn cael trafferth cysylltu â gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol i ddarganfod beth oedd yn digwydd. Roedd hyn yn aml yn golygu bod y sefyllfa'n teimlo allan o'u rheolaeth, gan eu gadael yn ofnus ac yn ddiymadferth. Roedd eirioli dros eu hanwyliaid a’u gofal o bell yn llawer anoddach nag o dan amgylchiadau arferol, ac weithiau’n amhosibl.

| “ | Cafodd fy ngŵr ei gludo i’r ysbyty a’i ddileu yn y bôn oherwydd oedran a chyflyrau eraill… roedd yn negyddol i Covid a chafodd ei roi ar ward lle roedd yn rhemp. Doedden ni ddim yn cael ymweld, doedd gennym ni ddim syniad beth oedd yn digwydd. Bu farw a chefais alwad ffôn am 3:15am yn dweud wrthyf ei fod wedi mynd.”

- Aelod o'r teulu mewn profedigaeth |

| “ | Doeddech chi ddim yn gallu mynd drwodd i unrhyw un, doeddech chi ddim yn gallu siarad â neb, roedden ni i gyd yn ffonio am ddiweddariad ... roedd fy nhad yn ffonio'n ddyddiol i'w [nain] gael ei rhyddhau i ni ... Mae gennym bopeth wedi'i osod yma [yn y cartref ]. Roedd ganddi wely trydan hyd yn oed, roedd gennym ni gadeiriau olwyn a phopeth iddi. Gallem fod wedi ei helpu.”

– Gofalwr am aelod oedrannus o'r teulu |

Roedd yn rhaid i deuluoedd, ffrindiau a chydweithwyr mewn profedigaeth a oedd yn gallu ymweld wneud hynny'n aml mewn amgylchiadau eithriadol a chyfyng iawn, fel arfer pan oedd y claf ar ddiwedd ei oes. Roedd yn rhaid i rai ddewis pwy fyddai'n ymweld oherwydd bod y niferoedd yn gyfyngedig. Nid oedd llawer yn cael cyffwrdd â'u hanwyliaid ac roedd yn rhaid iddynt wisgo PPE. Roedd y cyfyngiadau yn golygu bod rhai yn ymweld ar eu pen eu hunain, heb gefnogaeth teulu a ffrindiau. Roedd y profiad yn aml yn ddryslyd ac yn frawychus.

Clywsom lawer am hysbysiadau peidiwch â cheisio dadebru cardio-pwlmonaidd (DNACPR) a gofal diwedd oes a sut nad oedd penderfyniadau bob amser yn cael eu hesbonio i anwyliaid. Dywedodd rhai teuluoedd a ffrindiau mewn profedigaeth wrthym nad oeddent yn gwybod pa benderfyniadau a wnaed tan ar ôl i'w hanwyliaid farw, neu nad oeddent yn gwybod o hyd.

| “ | Gofynnodd y meddyg teulu i DNACPR fod yn ei le, roedd fy nhad yn gwybod am hyn a'r canlyniadau posibl, roedd eisiau byw, nid oedd eisiau un. Yna darganfyddais fod y meddyg teulu wedi ymweld eto’n ddirybudd gyda chais DNACPR, ac ni wnaethant erioed sôn wrthyf amdano.”

- Aelod o'r teulu mewn profedigaeth |

Yn ogystal â'r heriau niferus a wynebwyd gan anwyliaid mewn profedigaeth, roedd y straeon yn cynnwys enghreifftiau o weithwyr gofal iechyd yn cynnig gofal diwedd oes rhagorol yn ystod y pandemig. Disgrifiodd rhai pa mor gefnogol oedd y staff a faint roedd hyn wedi gwella gofal diwedd oes. Un enghraifft gyffredin oedd gweithwyr iechyd proffesiynol yn torri canllawiau Covid-19 i roi cysur corfforol i'w hanwyliaid a oedd yn marw.

Rwy'n cofio, roedd un nyrs fel, 'O, roedd eich tad eisiau i mi roi cwtsh i chi, a dweud, “Dyma gwtsh.”' Yn amlwg, nid oedd angen iddi wneud hynny...dydych chi ddim hyd yn oed i fod i i fod yn dod yn agos, ond dim ond y math yna o deimlad trugarog, ac yr oeddwn yn union fel, o fy Nuw, sydd mor adfywiol i weld mewn person meddygol.

I lawer, roedd colli anwyliaid a methu â dweud hwyl fawr yn gwneud eu colled yn anoddach i'w derbyn a dod i delerau â hi. Mae rhai yn cael eu gadael gyda'r euogrwydd llethol y dylent fod wedi gwneud mwy i'w hamddiffyn rhag Covid-19 neu rhag gorfod marw mewn lleoliadau gofal iechyd yn unig.

Covid hir

Mae Long Covid yn set o gyflyrau iechyd a symptomau hirdymor y mae rhai pobl yn eu datblygu ar ôl cael eu heintio â firws Covid-19. Cafodd Long Covid – ac mae’n parhau i gael – effaith ddramatig ac yn aml yn ddinistriol ar bobl. Dywedodd llawer o bobl sy’n byw gyda Long Covid wrthym sut yr oeddent am gael gwell cydnabyddiaeth a mwy o ddealltwriaeth ymhlith y cyhoedd o’r symptomau y maent yn parhau i’w profi a’r effaith enfawr y mae’n ei chael ar eu gallu i fyw eu bywydau. Pwysleisiodd rhai hefyd bwysigrwydd mwy o ymchwil a datblygu sy'n canolbwyntio ar driniaethau ar gyfer Long Covid.

| “ | Rydyn ni'n cael ein gadael ar ein pennau ein hunain nawr; nid ydym yn gwybod beth y gallwn ei wneud. Mae angen iddyn nhw gydnabod bod Covid yn gyflwr hirdymor neu gydol oes i rai pobl.”

- Person â Covid Hir |

Rhannodd y rhai sy'n byw gyda Long Covid y problemau iechyd parhaus niferus y maent wedi'u profi, gyda gwahanol fathau a difrifoldeb y symptomau. Mae'r rhain yn amrywio o ddoluriau a phoenau parhaus a niwl yr ymennydd, i flinder meddyliol gwanychol. Dywedodd llawer wrthym sut y mae eu bywydau wedi cael eu difrodi, a sut nad ydynt bellach yn gallu gweithio, cymdeithasu a chyflawni tasgau o ddydd i ddydd.

| “ | “Doeddwn i ddim yn gallu dychwelyd i’r gwaith na fy mywyd arferol fel gadawodd fi yn wanychlyd iawn gan flinder cronig, a dysautonomia1, cur pen cronig, niwl yr ymennydd a chanolbwyntio gwael.” - Person sy'n byw gyda Long Covid |

Mae cael mynediad i ofal yn aml wedi bod yn hynod heriol i bobl sy’n byw gyda Long Covid. Rhannodd rhai sut yr oeddent yn teimlo nad oedd gan eu meddyg teulu ddiddordeb yn eu symptomau neu nad oeddent yn eu credu. Mewn sgyrsiau â meddygon teulu neu weithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol eraill, roeddent yn aml yn teimlo eu bod yn cael eu diswyddo. Weithiau, clywsom y byddai gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol yn awgrymu a/neu’n ceisio eithrio achos arall i’w symptomau megis problemau gyda’u hiechyd meddwl neu gyflyrau iechyd sy’n bodoli eisoes.

Roedd gennym ni feddygon teulu yn gwrthod credu mewn Covid Hir yma, gyda llawer o rai eraill ddim yn cael profion am symptomau.

Mae'r profiadau a rannwyd hefyd yn tynnu sylw at anghysondebau yn y modd y mae pobl â Long Covid wedi cael eu trin. Mae wedi bod yn boenus i'r rhai â symptomau parhaus sydd wedi cael eu trosglwyddo rhwng gwahanol rannau o'r system gofal iechyd heb dderbyn y gofal sydd ei angen, os o gwbl - yn aml tra'n sâl iawn. Disgrifiasant deimlo'n segur a diymadferth, ac yn ansicr ble i droi.

| “ | Does neb eisiau gwybod, dwi'n teimlo'n anweledig. Rwy'n cael fy nhrin fel difrod cyfochrog. Mae'r rhwystredigaeth a'r dicter rwy'n ei deimlo yn anhygoel; golau nwy meddygol, diffyg cefnogaeth a'r ffordd y mae pobl eraill yn fy nhrin, mae'r meddyg teulu yn dweud wrthyf fy mod yn rhy gymhleth, oherwydd mae gennyf gymaint o adweithiau meddyginiaeth."

- Person sy'n byw gyda Long Covid |

Cyfeiriwyd rhai yn ôl at eu meddyg teulu gan arbenigwyr ar gyfer profion pellach neu i drin symptomau eraill, tra bod eraill yn cael eu hatgyfeirio at glinigau Long Covid neu eu cyfeirio at gyrsiau ar-lein unwaith yr oedd y rhain wedi'u sefydlu mewn rhai ardaloedd o'r DU ddiwedd 2020. Rhai pobl yn byw gyda Long Covid yn gweld clinigau a chyrsiau ar-lein yn ddefnyddiol ond roedd llawer yn derbyn gofal gwael heb unrhyw gymorth na thriniaeth wedi'u teilwra.

| “ | Felly, rydym yn dal i deimlo ein bod yn cael ein hanfon at y meddyg teulu ac nid yw'r meddygon teulu yn gwybod beth i'w wneud â ni, mae meddygon teulu yn brysur gyda llawer o bethau eraill. Ac nid oes gan hyd yn oed y meddygon teulu sy'n cydymdeimlo â'r ewyllys gorau yn y byd unrhyw syniad beth i'w wneud â ni. Mae angen rhywbeth mwy arbenigol yn y bôn.”

- Person sy'n byw gyda Long Covid |

Clywsom hefyd am weithwyr gofal iechyd sydd wedi cael eu heffeithio, ac yn parhau i gael eu heffeithio gan Long Covid. Awgrymodd rhai cyfranwyr fod y ffaith bod gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol wedi datblygu Long Covid wedi lleihau gallu gwasanaethau gofal iechyd i ddarparu gofal heddiw.

Gwarchod

Dywedodd pobl a oedd yn agored i niwed yn glinigol ac yn glinigol hynod agored i niwed wrthym eu bod yn ofni Covid-19 yn fawr ac yn deall pam y gofynnwyd iddynt warchod. Fodd bynnag, roedd llawer yn rhannu pa mor anodd oedd dilyn y cyngor gwarchod a’r effeithiau negyddol a gafodd hyn arnyn nhw a’u teuluoedd.

Fe wnes i ymdopi trwy wneud pethau eraill ond pe bawn i wedi mynd ychydig yn hirach, ychydig mwy o wythnosau, rwy’n meddwl y byddwn wedi mynd dros y dibyn i fod yn onest â chi. Roeddwn i'n cyrraedd y cam lle nad oeddwn yn gallu ymdopi...a dim ond cael [fy mam] i siarad â hi mewn gwirionedd, roedd hynny'n beth mawr oherwydd roedd fy mywyd cyfan yn eithaf cymdeithasol. Roeddwn yn unig, a cheisiais beidio â gadael i hynny effeithio gormod arnaf. Gwnaeth fy ngyrru’n hollol wallgof.

Roedd pobl a oedd yn gwarchod yn rhannu sut roedd gwneud hynny’n aml yn arwain at arwahanrwydd, unigrwydd ac ofn. Roedd eu hiechyd corfforol a meddyliol yn aml yn gwaethygu. Mae rhai yn dal i deimlo ofn gadael y tŷ - iddyn nhw, nid yw'r pandemig drosodd.

| “ | Cwymp trefn arferol, dioddefodd iechyd meddwl, dioddefodd iechyd corfforol. Wnaeth hi [ei mam] ddim bwyta llawer a dweud y gwir, collodd lawer o bwysau oherwydd doedd hi ddim yn iach…ond do, felly roedd hi’n dioddef llawer o iechyd meddwl ac o ran iechyd corfforol oherwydd diffyg pobl eraill yn fwy na dim. unrhyw beth, diffyg unrhyw fath o ryngweithio.”

– Gofalwr am rywun a oedd yn hynod agored i niwed yn glinigol |

Gadawyd llawer yn sownd gartref yn teimlo'n gyfyng, yn bryderus neu wedi diflasu, ac mewn rhai achosion maent yn dal i fod. Fe wnaethant rannu pa mor rhwystredig oedd methu â gwneud ymarfer corff a gofalu am eu hiechyd yn iawn.

| “ | Roedd cael gwybod fy mod mewn cymaint o risg o Covid-19 yn gwneud i mi deimlo allan o reolaeth ar fy iechyd ac o dan straen aruthrol. Roeddwn i'n ofni y byddwn i'n marw pe bawn i'n dal Covid-19. Trwy warchod, y risg wirioneddol i mi oedd methu â rheoli fy nghyflwr iechyd, a dwi’n ei wneud yn bennaf trwy ymarfer corff.”

– Person a oedd yn hynod agored i niwed yn glinigol |

Roedd rhai cyfranwyr yn fwy cadarnhaol am warchod. Roedd hyn yn aml oherwydd eu bod yn gyfforddus gartref neu'n gallu cadw'n brysur ac yn gadarnhaol. Roedd gallu datblygu trefn gyda phethau ystyrlon i'w gwneud yn eu helpu i ymdopi.

| “ | Gyda chymorth gardd…cefais fy sbwylio am bethau i'w gwneud. Felly mae'n debyg bod hynny wedi fy arbed yn llwyr, o ran iechyd meddwl ... nid oedd yn effeithio cymaint arna i mae'n debyg, â rhywun mewn stad o dai neu, fflatiau uchel neu rywbeth, nad oedd â'r gofod hwnnw y tu allan i fynd iddo.”

– Person a oedd yn hynod agored i niwed yn glinigol |

Disgrifiodd rhai pobl sy’n hynod agored i niwed yn glinigol sut y maent yn dal i warchod oherwydd nad yw’r risgiau sy’n gysylltiedig â Covid-19 wedi diflannu er eu mwyn. Maent yn parhau i ofni cymysgu ag eraill ac yn aml wedi colli cysylltiad â'u cymunedau. Maen nhw eisiau mwy o gydnabyddiaeth bod effaith y pandemig yn parhau i'r rhai sy'n hynod agored i niwed yn glinigol.

Mae [un] o fy ffrindiau yn hŷn, mae hi yn ei 70au, nid yw wedi dod yn ôl i'r eglwys... does ganddi hi ddim bywyd cymdeithasol o gwbl bellach... ei her fwyaf yw'r ffaith ei bod yn teimlo ei bod yn cael y wybodaeth hon , sy'n dweud wrthi ei bod yn agored i niwed, bod angen iddi amddiffyn ei hun, bod angen iddi gadw draw oddi wrth bobl, ei bod mewn perygl, ac nad yw ei risg wedi newid, a bod Covid-19 yn dal i fod o gwmpas. Ac felly, mae hi'n ei chael hi'n anodd cysoni'r ffaith ei fod yn teimlo fel bod y cyngor wedi newid, ac eto, mae'r risg yn dal i fod yr un peth... Ac felly, rwy'n meddwl bod llawer o ofn, o hyd, wedi'i lapio o amgylch hynny i gyd am pobl.

Sut yr addasodd y system gofal iechyd

Yn ogystal â'r effaith ar gleifion a'u hanwyliaid, dywedodd gweithwyr gofal iechyd wrthym hefyd am eu profiadau yn ystod y pandemig. Disgrifiwyd y gwaith a wnaethant i barhau i gynnig gofal cystal ag y gallent, gyda llawer yn cyfeirio at y newidiadau enfawr a wnaed mewn lleoliadau gofal iechyd.

Dywedodd llawer o gyfranwyr sy'n gweithio ym maes gofal iechyd fod cyflymder y newid yn llawer cyflymach yn ystod y pandemig nag yr oeddent wedi'i brofi o'r blaen. Mae'r straeon a rannwyd gyda ni yn amlygu rhai tensiynau ac anghytundebau ymhlith gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol a achosir gan heriau gweithredu rheolau. Roedd y rhain yn aml rhwng y rhai sy'n gweithio'n uniongyrchol gyda chleifion a'r rhai mewn rolau rheoli neu uwch arweinyddiaeth. Er enghraifft, roedd rhai cyfranwyr o'r farn bod uwch arweinwyr yn aml yn aros am arweiniad gan y llywodraeth neu Ymddiriedolaethau'r GIG ar beth i'w wneud yn hytrach na chymryd camau rhagweithiol.

Clywsom hefyd fod rhai gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol yn cwestiynu’n gynyddol y sail ar gyfer canllawiau Covid-19 wrth i’r pandemig fynd rhagddo. Roedd y pryderon hyn yn aml yn canolbwyntio ar a oedd y canllawiau’n seiliedig ar dystiolaeth o’r hyn a weithiodd i atal haint.

Dywedodd gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol wrthym sut y daethant i wybod am ganllawiau drwy’r cyfryngau a’u cyflogwyr ac am y gwahaniaethau yn y ffordd y gweithredwyd canllawiau Covid-19 ar draws gwahanol rannau o’r gwasanaeth iechyd.

Offer amddiffynnol personol (PPE)

Dywedodd gweithwyr gofal iechyd ar draws gwahanol leoliadau wrthym nad oedd ganddynt y PPE yr oedd ei angen arnynt, yn enwedig ar ddechrau’r pandemig. Roedd dyluniad a ffit rhai PPE hefyd yn achosi problemau sylweddol, gan ei gwneud yn anoddach i rai wneud eu gwaith ac achosi anghysur.

| “ | Roedd gen i ffrindiau yn gweithio yn ICU yn gwisgo bagiau bin.”

– Nyrs gymunedol |

Roeddwn i'n arfer ei rolio hyd at fy ngwasg, cael ffedog a defnyddio'r ffedog fel gwregys, ac yna hongian beiro oddi ar hwnnw hefyd. Felly, nid oedd y maint yn wych ac yna rydych chi'n fwy nag yr ydych chi'n meddwl ydych chi ac rydych chi'n taro llawer o eitemau oherwydd bod gennych chi fwy o led arnoch chi.

Clywsom enghreifftiau o sut yr effeithiodd PPE a oedd yn ffitio’n iawn yn gorfforol ar rai staff pan oeddent yn ei wisgo am oriau lawer. Roedd hyn yn cynnwys enghreifftiau o frechau, sensitifrwydd croen a marciau argraff o wisgo masgiau am gyfnodau hir.

Roedd PPE hefyd yn gwneud cyfathrebu llafar rhwng gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol a chleifion yn fwy anodd. Roedd hon yn her arbennig i gleifion ag anghenion cyfathrebu ychwanegol, gan gynnwys pobl â nam ar eu clyw a phobl awtistig sy'n dibynnu ar fynegiant wyneb i gyfathrebu.

| “ | Rydych chi'n dweud, 'Rwy'n fyddar,' ac maen nhw'n siarad â chi trwy fwgwd, a byddaf yn dweud, 'Rwy'n fyddar.' Maen nhw, fel, 'O, na, na, ni allaf dynnu fy mwgwd. Efallai y byddwch chi'n rhoi Covid-19 i mi.' Rwy'n debyg, 'Wel, wyddoch chi, byddaf yn sefyll draw fan hyn, rydych chi'n sefyll draw acw. Tynnwch eich mwgwd i lawr, byddaf fwy na 2 fetr i ffwrdd,' ac fe wrthodon nhw o hyd. Roedd hynny’n anodd iawn ac yna’n llythrennol allwch chi ddim gweld eu ceg na’u hwyneb, felly does gennych chi ddim gobaith o’u deall.”

- Person byddar |

Roedd gan weithwyr gofal iechyd mewn gwahanol leoliadau argraffiadau cymysg o eglurder canllawiau a gofynion o ran profi. Roeddent yn cofio bod canllawiau hunan-ynysu yn arbennig o llym ar ddechrau'r pandemig, a oedd yn golygu nad oeddent yn gallu gweithio ar adegau pan oeddent yn iach.

Gofal sylfaenol

Roedd y rhai a oedd yn gweithio ym maes gofal sylfaenol yn aml yn rhannu sut roedd addasu i’r pandemig wedi bod yn heriol ac yn ei gwneud hi’n anoddach cynnig gofal da i gleifion. Serch hynny, bu iddynt fyfyrio ar faint y llwyddasant i newid a sut yr oedd hyn yn caniatáu iddynt ofalu am lawer o'u cleifion.

| “ | Fe wnaethon ni addasu, a dwi'n meddwl ein bod ni wedi newid. Rwy'n meddwl ein bod wedi gwneud yr hyn yr oedd yn rhaid i ni ei wneud. Roedd yn ddeinamig drwy'r amser a dweud y gwir, onid oedd? Roedd yn newid drwy’r amser, ac fe wnaethom ein gorau, rwy’n meddwl, i fynd i wneud yr hyn oedd yn rhaid i ni ei wneud.”

– nyrs meddyg teulu |

Teimlai rhai nad oedd meddygon teulu a fferyllwyr cymunedol yn cael eu hystyried yn briodol ac nad ymgynghorwyd â hwy, a bod yr ymateb pandemig mewn ysbytai yn cael ei flaenoriaethu. Roeddent yn rhwystredig ynghylch canllawiau a oedd yn newid yn gyflym, heb fawr o rybudd ac yn aml diffyg eglurder ynghylch sut yr oedd meddygfeydd teulu neu fferyllfeydd i fod i ymateb.

Clywsom am rai gwasanaethau meddygon teulu lleol yn cydweithio i rannu syniadau a chyfuno staff ac adnoddau, ac am 'ganolfannau Covid-19' i drin cleifion a lleihau derbyniadau i'r ysbyty. Roedd y dulliau hyn yn cael eu hystyried yn gadarnhaol ar y cyfan, gan roi mwy o hyder i’r rhai sy’n gweithio ym maes gofal sylfaenol wrth asesu a thrin Covid-19.

Myfyriodd meddygon teulu ar sut achosodd y pandemig rai problemau iechyd newydd. Er enghraifft, roedd rhai o’r farn bod pellhau cymdeithasol wedi arwain at fwy o arwahanrwydd, gan gyfrannu yn ei dro at fwy o faterion iechyd meddwl ymhlith eu cleifion.

Ysbytai

Clywsom gan weithwyr gofal iechyd am sut y gwnaeth ysbytai newidiadau i reoli’r mewnlifiad disgwyliedig o gleifion Covid-19. Dywedasant wrthym am y cynnwrf ar draws gwahanol rolau mewn ysbytai, nid ymhlith staff clinigol yn unig. Er bod rhai gweithwyr gofal iechyd yn gadarnhaol ynghylch y ffordd yr oedd yr ymateb yn cael ei reoli, dywedodd eraill nad oedd digon o ystyriaeth wedi'i rhoi iddo.

Gwnaed newidiadau enfawr. Ailddyrannu ardaloedd, ailddyrannu staff, pawb yn symud o le i le, newid yr hyn yr oeddent yn ei wneud.

| “ | Cafodd llawer o staff eu hadleoli i wahanol feysydd clinigol i ffwrdd o'r lle y maent fel arfer yn gweithio i gynorthwyo gyda'r ymateb i Covid - cafodd yr aelodau hyn o staff eu “taflu i mewn i'r pen dwfn” heb fawr o hyfforddiant ychwanegol a dim dewis ynghylch ble y cawsant eu hanfon. Cafodd hyn hefyd effaith ar lwybrau hyfforddi llawer o feddygon iau.”

-Meddyg ysbyty |

Roedd cynllunio a darparu gofal yn parhau i fod yn heriol yn ddiweddarach yn y pandemig. Rhannodd llawer o gyfranwyr sut y daeth gwneud newidiadau i ofal ysbyty yn fwy anodd oherwydd blinder staff a morâl isel. Disgrifiodd rhai ddiffyg cynllunio o ran sut i flaenoriaethu gofal nad yw'n ofal brys a thrin mwy o gleifion wrth i gyfyngiadau pandemig ddechrau lleddfu.

| “ | Nid oedd unrhyw gyngor ar sut i gamu'n ôl o unrhyw beth ac nid oedd unrhyw gymorth o gwbl i ddad-ddwysáu. Ac nid oedd yn teimlo, i ni, unrhyw synnwyr o ddysgu, 'Iawn, yr hyn a wnaethom yn y don gyntaf'.”

-Meddyg ysbyty |

Gofal brys a brys

Roedd pwysau aruthrol ar lawer o adrannau brys (EDs) yn ystod y pandemig, gyda heriau’n gysylltiedig ag addasrwydd adeiladau, prinder staff a chyfnodau o alw cynyddol am ofal brys. Roedd y pwysau oedd arnynt yn amrywio rhwng gwahanol adrannau achosion brys ac wedi newid ar wahanol gamau o'r pandemig.

Dywedodd llawer o'r rhai sy'n gweithio ym maes gofal brys nad oeddent ar adegau yn gallu cynnal rheolaethau heintiau oherwydd bod nifer fawr o gleifion a dim digon o le. Dywedodd rhai staff Adrannau Achosion Brys wrthym am orfod gwneud penderfyniadau ynghylch blaenoriaethu gofal a throsglwyddo cleifion i ofal dwys (ICU neu ITU), ac am ba mor anodd oedd y rhain oherwydd pa mor ddifrifol y gallent fod i gleifion.

| “ | Roedden ni’n cael ein gorfodi i chwarae Duw wrth benderfynu pwy oedd yn mynd i ITU – pwy gafodd newid i fyw a phwy oedd ddim.”

- Nyrs ysbyty |

Dywedodd cyfranwyr eraill a oedd yn gweithio mewn Adrannau Achosion Brys eu bod yn gweld llai o gleifion nag arfer ar adegau oherwydd bod pobl yn rhy ofnus i geisio triniaeth. Roedd llai o alw yn caniatáu i staff mewn rhai adrannau achosion brys dreulio mwy o amser yn gofalu am gleifion unigol nag yr oeddent yn gallu cyn y pandemig.

Dywedodd parafeddygon wrthym faint o bwysau oedd arnynt a faint y newidiodd eu rolau. Disgrifiasant aros y tu allan i ysbytai mewn ambiwlansys gyda chleifion sâl, yn aml am gyfnodau hir iawn. Roedd hyn yn golygu bod yn rhaid i barafeddygon ofalu am gleifion mewn ambiwlansys a rhybuddio staff ysbytai am newidiadau yn eu cyflwr.

Clywsom gan rai o’r rhai sy’n delio â galwadau 111 a 999 y GIG am y pwysau o orfod delio â nifer fawr o alwadau gan bobl bryderus a sâl iawn. Rhoesant enghreifftiau o'r problemau a achosir gan brinder ambiwlansys. Roedd hyn yn peri gofid arbennig i'r rhai sy'n delio â galwadau.

| “ | Byddent [galwyr] yn ein ffonio, a byddem fel, 'Ie, ond mae angen ambiwlans arnoch,' felly byddem yn mynd drwodd i ambiwlans, a byddent fel, 'Ond nid oes gennym ni ddim byd. i anfon.' Roedd hynny’n peri gofid.”

– triniwr galwadau GIG 111 |

Yr effaith ar y gweithlu gofal iechyd

Ysgogodd ymdeimlad o bwrpas a rennir lawer o weithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol yn ystod y pandemig. Ond dywedodd rhai fod yr ymdeimlad hwn o bwrpas wedi diflannu wrth i'r pandemig fynd yn ei flaen, gan gynyddu gorfoledd ymhlith staff wrth i donnau'r pandemig barhau.

| “ | Roeddech chi'n helpu pobl eraill. Roeddech mewn gwirionedd yn darparu gwasanaeth gwerthfawr. Fe wnaeth i chi deimlo'n falch o'r hyn wnaethoch chi."

- Fferyllydd ysbyty |

Rwy'n meddwl ar lefel bersonol, daeth yn anoddach ac yn anoddach. Fe wnaethoch chi flino mwy a mwy. Mae'n debyg ei fod wedi arwain at rywfaint o bryder. Anodd delio â phethau. Rwy’n meddwl mai dyna oedd yr heriau.

Yn aml roedd yn rhaid i staff sy'n gweithio ar draws gwahanol rolau ac mewn gwahanol rannau o systemau gofal iechyd ysgwyddo llwythi gwaith enfawr. Ychwanegodd hyn at eu swyddi oedd eisoes dan straen. Dywedodd gweithwyr gofal iechyd wrthym yn gyson fod cydweithwyr i ffwrdd yn sâl neu angen hunanynysu wedi ychwanegu at bwysau llwyth gwaith.

Clywsom fod staff yn cael eu hadleoli weithiau i leddfu’r pwysau ar dimau, ond dywedodd cyfranwyr ei bod yn heriol addysgu’r sgiliau arbenigol a’r arbenigedd sydd eu hangen i weithio mewn meysydd newydd yn gyflym. Er enghraifft, roedd nyrsys a drosglwyddwyd i weithio mewn ICUs Covid-19 yn rhannu rhai o'r profiadau rheng flaen mwyaf heriol.

| “ | Roeddwn i’n teimlo’n ddi-rym o gael fy ngorfodi i rolau anghyfarwydd heb hyfforddiant priodol.”

– Nyrs gymunedol i blant |

| “ | Roedd nyrs yr ICU yn goruchwylio … mewn gwirionedd yn gofalu am y claf, gan mai dim ond yn ei chynorthwyo yr oeddech chi, yn gwirio cyffuriau ac ati. y cwpl o ddyddiau cyntaf, ac yna y tu hwnt i hynny, chi oedd yn ei wneud mewn gwirionedd.”

- Nyrs ysbyty |

Rhannodd llawer o weithwyr gofal iechyd y cyfyng-gyngor moesegol yr oeddent yn ei wynebu ynghylch canllawiau Covid-19. Roedd y rhain yn aml yn benodol i’w rôl a’u profiad pandemig, ond roedd rhai themâu cyffredin. Er enghraifft, dywedodd rhai gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol nad oeddent yn dilyn canllawiau fel y gallent ddangos mwy o dosturi tuag at gleifion, teuluoedd a chydweithwyr.

Un o'r profiadau mwyaf gofidus a dirdynnol i lawer o weithwyr gofal iechyd oedd delio â marwolaeth ar raddfa nad oeddent erioed wedi dod ar ei thraws o'r blaen. Disgrifiodd rhai y niwed i'w hiechyd meddwl o ganlyniad. Roeddent yn dweud yn aml mai methu â gweld eu hanwyliaid oedd yn marw oedd un o'r pethau anoddaf yr oedd yn rhaid iddynt ymdopi ag ef.

Roedd fel parth rhyfel, dros nos daeth 18 o bobl yn bositif am Covid-19 heb unman i'w ynysu. Roeddent yn gollwng fel pryfed, roedd yn ofnadwy. Ni allwch ddiystyru'r hyn a wnaeth hyn i staff nyrsio, roedd methu â chynnig cysur i gleifion yn ddinistriol i'r enaid.

| “ | Daethom yn imiwn iddo. Fe wnaeth ein dad-ddyneiddio ni ychydig, rwy'n meddwl, ar y pryd. Teimlais hynny, a theimlais ei fod yn anodd delio ag ef.

– rheolwr practis meddyg teulu |

Pan oedd gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol yn profi sefyllfaoedd trallodus a phwysau llwyth gwaith, roedd rhai'n cael cynnig cymorth emosiynol, ac yn gwneud defnydd ohono. Roedd cymorth gan gymheiriaid o fewn timau hefyd yn bwysig i helpu staff i ymdopi â'r heriau yr oeddent yn eu hwynebu. Fodd bynnag, roedd hyn yn anghyson, ac nid oedd rhai gweithwyr gofal iechyd yn cael cynnig unrhyw gymorth gyda'u hiechyd meddwl.

| “ | “Rwy’n teimlo ein bod yn cael gwybod o hyd am yr hyn yr oedd yr ysbyty yn ei wneud ar gyfer staff a phethau, ond nid wyf yn meddwl eu bod erioed wedi gofyn i’r staff beth fyddai’n gwneud gwahaniaeth i fod yn y gwaith. Dwi’n meddwl mai dyna oedd y pethau bach hefyd, fel bydden nhw wedi dweud gallu parcio…gallu mynd am ginio mewn lle ymlacio.”

-Meddyg ysbyty |

Roedd rhai aelodau o staff yn dawelach, neu’n cael cyfnodau tawelach, yn ystod y pandemig oherwydd bod cleifion yn cadw draw neu oherwydd sut roedd gofal yn cael ei ad-drefnu. Er bod hyn fel arfer yn lleihau'r pwysau a'r straen uniongyrchol yr oeddent yn ei deimlo, roedd rhai'n teimlo'n euog bod gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol eraill dan fwy o straen. Roedd y rhai a oedd yn llai prysur hefyd yn poeni am y cleifion y byddent fel arfer yn eu gweld ac a oeddent yn cael y gofal a'r driniaeth yr oedd eu hangen arnynt.

Disgrifiodd rhai cyfranwyr effaith barhaol gweithio ym maes gofal iechyd yn ystod y pandemig. Fe wnaethant rannu sut roedd eu hiechyd meddwl bellach yn waeth nag y bu. Clywsom hefyd enghreifftiau o weithwyr proffesiynol a oedd wedi wynebu problemau personol fel tor-perthynas a oedd yn eu barn nhw o leiaf yn rhannol oherwydd eu profiadau yn y pandemig. Yn anffodus, dywedodd rhai gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol wrthym am orfod newid rolau neu roi’r gorau i weithio oherwydd cymaint y dirywiodd eu hiechyd meddwl yn ystod y pandemig.

| “ | Nid wyf yn meddwl fy mod wedi dod yn ôl i 100% o sut yr oeddwn fel arfer. Mae'n cymryd ei doll. Ond mae bron fel cael y darn hwn o bapur, sy'n neis, a fflat, ac yn syth, ac yna rydych chi wedi'i grychu ac yna rydych chi'n ceisio sythu'r darn hwnnw o bapur eto. Mae wedi cynyddu o hyd, ni waeth faint rydych chi'n ceisio ei sythu."

- Parafeddyg |

Ailadeiladu ymddiriedaeth mewn penderfyniadau am ofal iechyd

Rhannodd rhai cyfranwyr sut roedd eu hymddiriedaeth mewn systemau gofal iechyd wedi cael ei hysgwyd gan yr hyn a ddigwyddodd gan ddadlau bod hyn yn bryder i lawer ar draws cymdeithas. Roedd hyn yn aml yn ymwneud llai â'r gofal a gawsant gan weithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol unigol ac yn fwy am y penderfyniadau a wnaethpwyd ynghylch trefnu a darparu gofal.

Mae ymddiriedaeth mewn gwasanaethau gan y cyhoedd wedi mynd oherwydd y ffordd y cawsant eu trin yn y cloeon.

Mae llawer o'u rhesymau dros beidio ag ymddiried yn y penderfyniadau a wneir am ofal iechyd eisoes wedi'u hamlygu. Roeddent yn poeni am fynediad at ofal iechyd ac a fydd systemau gofal iechyd yn gallu gwella o'r pandemig. I lawer o gyfranwyr, roedd gwneud mwy i gadw ac ailadeiladu ymddiriedaeth y cyhoedd mewn gofal iechyd yn cael ei ystyried yn flaenoriaeth bwysig - nawr ac wrth ddelio â phandemigau ac argyfyngau yn y dyfodol.

Rhannodd miloedd o bobl eu profiadau am systemau gofal iechyd yn ystod y pandemig gyda ni. Yn yr adroddiad hwn rydym yn adeiladu ar y crynodeb hwn, gan amlygu’n fanylach y themâu allweddol o’r straeon a glywsom.

- Term ymbarél yw Dysautonomia sy'n disgrifio anhwylder ar y system nerfol awtonomig, sy'n rheoli swyddogaethau'r corff gan gynnwys rheoleiddio cyfradd curiad ein calon, pwysedd gwaed, tymheredd, treuliad ac anadlu. Pan fydd dadreoleiddio yn digwydd, gall y swyddogaethau hyn gael eu newid, gan arwain at ystod o symptomau corfforol a gwybyddol.

Adroddiad Llawn

1. Rhagymadrodd

Mae'r ddogfen hon yn cyflwyno'r straeon a rennir ag Every Story Matters yn ymwneud â systemau gofal iechyd y DU yn ystod y pandemig.

Cefndir a nodau

Mae Every Story Matters yn gyfle i bobl ledled y DU rannu eu profiad o’r pandemig ag Ymchwiliad Covid-19 y DU. Mae pob stori a rennir wedi'i dadansoddi a'i throi'n adroddiad â thema. Cyflwynir yr adroddiadau hyn i'r Ymchwiliad fel tystiolaeth. Wrth wneud hynny, bydd canfyddiadau ac argymhellion yr Ymchwiliad yn cael eu llywio gan brofiadau'r rhai yr effeithiwyd arnynt gan y pandemig.

Mae’r ddogfen hon yn dwyn ynghyd yr hyn a ddywedodd pobl wrthym am eu profiadau o systemau gofal iechyd y DU1 yn ystod y pandemig.

Mae Ymchwiliad Covid-19 y DU yn ystyried gwahanol agweddau ar y pandemig a sut yr effeithiodd ar bobl. Mae hyn yn golygu y bydd rhai pynciau yn cael sylw mewn adroddiadau modiwl eraill. Felly, nid yw'r holl brofiadau a rennir gyda Mae Pob Stori'n Bwysig wedi'u cynnwys yn y ddogfen hon. Er enghraifft, bydd profiadau o ofal cymdeithasol oedolion a’r effaith ar blant a phobl ifanc yn cael eu harchwilio mewn modiwlau diweddarach a’u cynnwys yn nogfennau Mae Pob Stori’n Bwysig yn y dyfodol.

Sut mae pobl yn rhannu eu profiadau

Rydym wedi casglu straeon pobl ar gyfer Modiwl 3 mewn sawl ffordd wahanol. Mae hyn yn cynnwys:

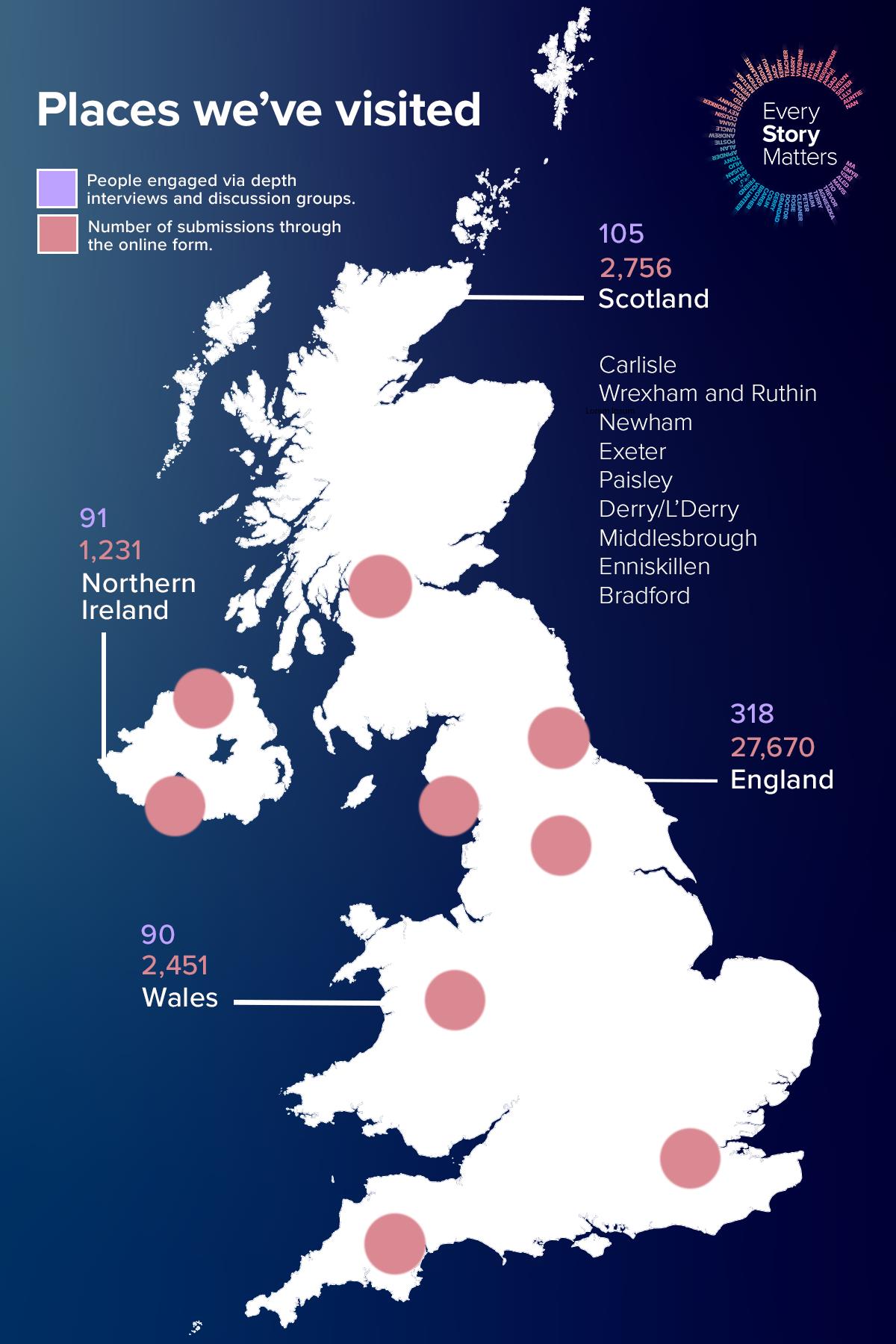

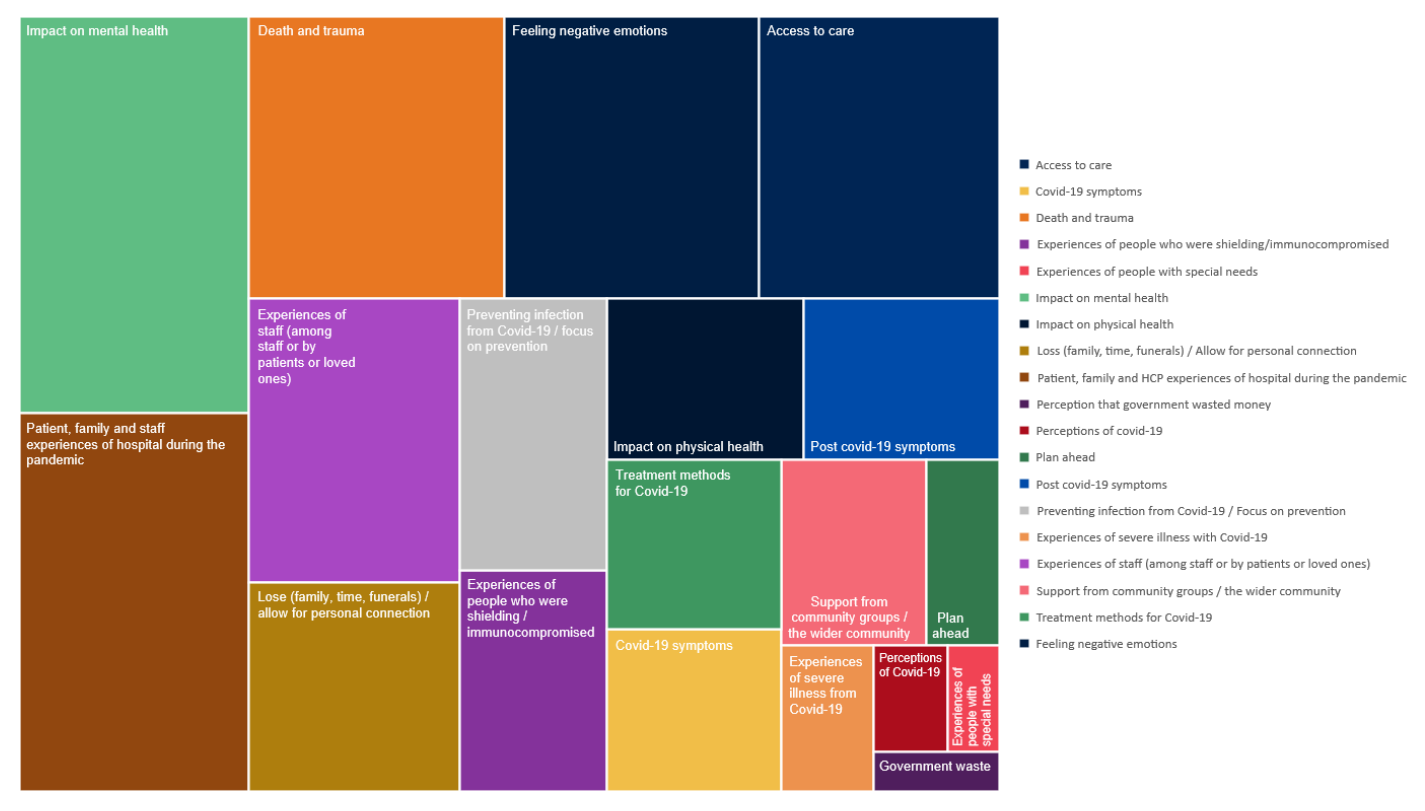

- Gwahoddwyd aelodau'r cyhoedd i lenwi ffurflen ar-lein trwy wefan yr Ymchwiliad (cynigiwyd ffurflenni papur hefyd i gyfranwyr a'u rhoi ar y ffurflen ar-lein i'w dadansoddi). Mae hyn yn caniatáu iddynt ateb tri chwestiwn eang, penagored am eu profiad pandemig. Mae'r ffurflen yn gofyn cwestiynau eraill i gasglu gwybodaeth gefndir amdanynt (fel eu hoedran, rhyw ac ethnigrwydd). Mae hyn yn caniatáu inni glywed gan nifer fawr iawn o bobl am eu profiadau pandemig. Mae'r ymatebion i'r ffurflen ar-lein yn cael eu cyflwyno'n ddienw. Ar gyfer Modiwl 3, dadansoddwyd 32,681 o straeon yn ymwneud â systemau gofal iechyd y DU. Mae hyn yn cynnwys 27,670 o straeon o Loegr, 2,756 o’r Alban, 2,451 o Gymru a 1,231 o Ogledd Iwerddon (roedd cyfranwyr yn gallu dewis mwy nag un wlad yn y DU ar-lein, felly bydd y cyfanswm yn uwch na nifer yr ymatebion a dderbyniwyd). Mae'r ymatebion wedi'u dadansoddi trwy brosesu iaith naturiol (NLP), sy'n defnyddio dysgu peirianyddol i helpu i drefnu'r data mewn ffordd ystyrlon. Yna defnyddir cyfuniad o ddadansoddiad algorithmig ac adolygiad dynol i archwilio'r straeon ymhellach.

- Tîm Mae Pob Stori yn Bwysig teithio i 17 o drefi a dinasoedd ledled Cymru, Lloegr, yr Alban a Gogledd Iwerddon, i roi cyfle i bobl rannu eu profiad pandemig yn bersonol yn eu cymunedau lleol. Cynhaliwyd sesiynau gwrando rhithwir hefyd lle'r oedd y dull hwnnw'n cael ei ffafrio. Buom yn gweithio gyda llawer o elusennau a grwpiau cymunedol llawr gwlad (a restrir yn y cydnabyddiaethau isod) i siarad â'r rhai yr effeithiwyd arnynt gan y pandemig mewn ffyrdd penodol. Mae hyn yn cynnwys teuluoedd mewn profedigaeth, pobl sy'n byw gyda Long Covid a PIMS-Ts, teuluoedd sy'n agored i niwed yn glinigol, pobl anabl, ffoaduriaid, pobl o gefndiroedd lleiafrifoedd ethnig a gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol. Ysgrifennwyd adroddiadau cryno ar gyfer pob digwyddiad, eu rhannu â chyfranogwyr y digwyddiad, a'u defnyddio i lywio'r ddogfen hon.

- Comisiynwyd consortiwm o bartneriaid ymchwil cymdeithasol ac ymgysylltu â’r gymuned gan Every Story Matters i’w gynnal cyfweliadau manwl a grwpiau trafod gyda'r rhai yr effeithir arnynt fwyaf gan y pandemig a'r rhai sy'n llai tebygol o ymateb mewn ffyrdd eraill. Roedd y cyfweliadau a’r grwpiau trafod hyn yn canolbwyntio ar y Prif Linellau Ymholi (KLOEs) ar gyfer Modiwl 3. Yn gyfan gwbl, cyfrannodd 604 o bobl ledled Cymru, Lloegr, yr Alban a Gogledd Iwerddon fel hyn rhwng Chwefror 2023 a Chwefror 2024. Mae hyn yn cynnwys 450 o gyfweliadau manwl â :

-

- Pobl yr effeithir yn uniongyrchol arnynt gan Covid-19.

- Pobl yr effeithir arnynt yn anuniongyrchol gan Covid-19.

- Gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol a staff cymorth.

- Grwpiau proffesiynol eraill sy'n gweithio yn y system gofal iechyd.

Ymgysylltwyd â 154 o bobl eraill o gymunedau y gwyddys eu bod yn profi anghydraddoldebau iechyd drwy allgymorth cymunedol. Helpodd y grwpiau trafod cymunedol a chyfweliadau hyn i sicrhau bod yr Ymchwiliad yn clywed gan bobl na fyddai'n bosibl eu cyrraedd mewn ffyrdd eraill. Roedd y bobl y siaradom â nhw yn cynnwys:

-

- Pobl o gefndir ethnig lleiafrifol.

- Pobl ag anabledd gan gynnwys nam ar y golwg, nam ar y clyw a'r rheini

ag anabledd dysgu. - Pobl o ardaloedd mwy difreintiedig yn y DU.

Cafodd yr holl gyfweliadau manwl a grwpiau trafod eu recordio, eu trawsgrifio, eu codio a'u dadansoddi trwy adolygiad dynol i nodi themâu allweddol sy'n berthnasol i Modiwl 3 KLOEs.

Mae nifer y bobl a rannodd eu straeon ym mhob gwlad yn y DU drwy’r ffurflen ar-lein, digwyddiadau gwrando a chyfweliadau ymchwil a grwpiau trafod i’w gweld isod:

Ffigur 1: Ymgysylltiad Mae Pob Stori o Bwys ledled y DU

I gael rhagor o wybodaeth am sut y gwnaethom wrando ar bobl a’r dulliau a ddefnyddiwyd i ddadansoddi straeon, gweler yr atodiadau.

Nodiadau am gyflwyniad a dehongliad straeon

Mae’n bwysig nodi nad yw’r straeon a gasglwyd drwy Every Story Matters yn cynrychioli’r holl brofiadau o ofal iechyd y DU yn ystod y pandemig nac o farn gyhoeddus y DU. Effeithiodd y pandemig ar bawb yn y DU mewn gwahanol ffyrdd, ac er bod digwyddiadau a ffeithiau allweddol, rydym yn cydnabod pwysigrwydd profiad unigryw pawb o'r hyn a ddigwyddodd. Nod yr adroddiad hwn yw adlewyrchu'r gwahanol brofiadau a rannwyd gyda ni heb gysoni'r amrywiad neu'r cyfrifon gwahanol.

Rydym wedi ceisio adlewyrchu’r amrywiaeth o straeon a glywsom, a all olygu bod rhai straeon a gyflwynir yma yn wahanol i’r hyn a brofodd pobl eraill yn y DU, ac weithiau’n cyferbynnu â chonsensws neu dystiolaeth wyddonol. O ystyried hyn, mae'r adroddiad hwn yn ceisio darparu cydbwysedd, naws, a chyd-destun o amgylch y straeon a rennir gyda ni.

Archwilir rhai straeon yn fanylach trwy ddyfyniadau ac astudiaethau achos. Mae'r rhain wedi'u dewis i dynnu sylw at y gwahanol fathau o brofiadau y clywsom amdanynt a'r effaith a gafodd y rhain ar bobl. Mae'r dyfyniadau a'r astudiaethau achos yn helpu i seilio'r adroddiad ar yr hyn a rannodd pobl yn eu geiriau eu hunain. Mae'r cyfraniadau wedi'u gwneud yn ddienw. Rydym wedi defnyddio ffugenwau ar gyfer astudiaethau achos sydd wedi'u tynnu o'r cyfweliad manwl a'r grwpiau trafod. Mae astudiaethau achos yn seiliedig ar brofiadau a rennir mewn ffyrdd eraill wedi'u gwneud yn ddienw.

Drwy gydol yr adroddiad, rydym yn cyfeirio at bobl a rannodd eu straeon gyda Every Story Matters fel 'cyfranwyr'. Lle bo'n briodol, rydym hefyd wedi disgrifio mwy amdanynt (er enghraifft, gwahanol fathau o staff sy'n gweithio ym maes gofal iechyd) neu'r rheswm pam y bu iddynt rannu eu stori (er enghraifft fel cleifion neu anwyliaid) i helpu i egluro cyd-destun a pherthnasedd eu profiad.

Yn ogystal â rhannu eu profiadau, gofynnwyd i gyfranwyr fyfyrio ar yr hyn y gall yr Ymchwiliad ei ddysgu o'u profiad. Canolbwyntiodd rhai ar sut y dylid bod wedi ymdrin yn well â phroblemau penodol a wynebwyd ganddynt. Rhannodd eraill yr hyn a oedd wedi mynd yn dda yn eu barn nhw. Clywsom rai themâu eang ar draws eu myfyrdodau, a chaiff y rhain eu hamlygu drwy gydol yr adroddiad.

Mae’n amlwg o’r straeon bod rhai a ymatebodd yn llawn cymhelliant i wneud hynny. Am y rheswm hwn, ni ddylid ystyried bod dadansoddiad o ymatebion i’r ffurflen ar-lein yn gynrychioliadol o brofiadau’r cyhoedd o’r pandemig yn ehangach. Yn lle hynny, maen nhw’n adlewyrchu profiadau’r rhai a ddewisodd rannu eu stori gyda Every Story Matters.

Strwythur yr adroddiad

Mae'r ddogfen hon wedi'i strwythuro i alluogi darllenwyr i ddeall sut yr effeithiodd y pandemig ar wahanol rannau o'r system gofal iechyd a grwpiau penodol o bobl.

Mae’n dechrau drwy archwilio profiadau mewn Gofal Sylfaenol (Pennod 2), Ysbytai (Pennod 3 a 4), a Gofal Argyfwng a Brys (Pennod 5). Yna mae’r adroddiad yn edrych ar effeithiau sy’n gysylltiedig â phrofion PPE a Covid-19 (Pennod 6), profiadau o ganllawiau’r llywodraeth a’r sector gofal iechyd (Pennod 7) ac effaith y pandemig ar weithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol (Pennod 8).

Yna mae’r ddogfen yn troi at brofiadau penodol o ofal iechyd yn ystod y pandemig, gan gynnwys gofal diwedd oes a phrofedigaeth (Pennod 9), Long Covid (Pennod 10), Gwarchod (Pennod 11) a’r defnydd o wasanaethau mamolaeth (Pennod 12).

- Rydym wedi cyfeirio at systemau gofal iechyd y DU yn hytrach na’r GIG lle bo modd drwy gydol yr adroddiad hwn er mwyn adlewyrchu’r gwahaniaethau yn y systemau gofal iechyd ar draws pedair gwlad y DU.

2. Gofal sylfaenol: profiadau gweithwyr gofal iechyd proffesiynol a chleifion |

|

Gofal sylfaenol fel arfer yw'r pwynt cyswllt cyntaf pan fydd angen cyngor neu driniaeth iechyd ar bobl, ac mae'n gweithredu fel 'drws ffrynt' i systemau gofal iechyd. Mae gofal sylfaenol yn cynnwys practis cyffredinol, fferylliaeth gymunedol, deintyddol. Yn y bennod hon rydym yn rhannu’r straeon a glywsom gan feddygon teulu, nyrsys meddygon teulu, rheolwyr practis, a fferyllwyr cymunedol ochr yn ochr â phrofiadau cleifion o gael mynediad at wasanaethau gofal sylfaenol a’u defnyddio.

Ymateb i'r pandemig

Roedd camau cynnar y pandemig yn ddryslyd ac yn peri straen i feddygon teulu, fferyllwyr cymunedol ac eraill mewn gofal sylfaenol. Roedd cyfranwyr a oedd yn gweithio ym maes gofal sylfaenol yn ei chael yn heriol oherwydd eu bod am barhau i ofalu am eu cleifion, ond nid oedd llawer o eglurder ynghylch sut y dylent ymateb.

Gan fyfyrio ar eu profiad, dywedodd llawer o gyfranwyr nad oedd cynllunio strategol ar gyfer gofal sylfaenol wedi bod yn ddigon da. Roedd rhai o'r farn bod y llywodraeth a sefydliadau gofal iechyd lleol yn araf i ymateb, heb fawr o gyngor. Roedd y cyfranwyr hyn yn rhwystredig oherwydd nad oedd ganddynt y cymorth yr oedd ei angen arnynt pan ddechreuodd y pandemig.

| “ | Rwy'n meddwl lle'r oedd gan ysbytai gynlluniau torfol a chynlluniau brys, o fewn gofal sylfaenol roedd yn dameidiog ac yn ddatgymalog iawn ac, 'O, chi sydd i benderfynu.' Ac rwy'n cael hynny, ond roedd yn anodd ei wneud.”

– rheolwr practis meddyg teulu |

Teimlai cyfranwyr fod cynllunio brys yn canolbwyntio mwy ar ysbytai yn hytrach na gofal sylfaenol, oherwydd gallai newidiadau gael eu rheoli'n ganolog mewn ysbytai.

| “ | Rwy'n meddwl lle'r oedd gan ysbytai gynlluniau torfol a chynlluniau brys, o fewn gofal sylfaenol roedd yn dameidiog ac yn ddatgymalog iawn ac, 'O, chi sydd i benderfynu.' Ac rwy'n cael hynny, ond roedd yn anodd ei wneud.”

– rheolwr practis meddyg teulu |

Fodd bynnag, dywedodd llawer o feddygon teulu wrthym fod annibyniaeth practisau meddygon teulu yn caniatáu iddynt newid eu gwasanaethau’n gyflym a herio awgrymiadau byrddau iechyd nad oeddent yn credu eu bod o gymorth. Dywedodd y cyfranwyr hyn eu bod wedi gallu datblygu dulliau o ddarparu gwasanaethau a oedd yn gweddu i'r cyd-destun lleol.

| “ | Mae meddygon teulu yn griw eithaf dyfeisgar, arloesol o bobl. Rwy'n meddwl bod hynny'n cael ei helpu yn ôl pob tebyg gan eu bod yn cael eu busnesau eu hunain, maent yn cydnabod 'mae yna sefyllfa ac mae angen inni ddod o hyd i ateb'.”

- Meddyg Teulu |

Wrth i amser fynd yn ei flaen, rhannwyd mwy o arweiniad, ond dywedodd llawer fod hyn wedi dod yn llethol. Dywedodd staff gofal sylfaenol wrthym ei bod yn amhosibl cadw i fyny â phopeth a ddywedwyd wrthynt a gweithredu arno.

| “ | Roedd pethau swyddogol gan y bwrdd iechyd yn araf iawn… weithiau roedd gan yr e-bost hwnnw 20 atodiad iddo, a fyddai’n cael ei anfon allan am, fel, 7 o’r gloch ar nos Fawrth neu rywbeth chwerthinllyd, pan nad oedd yr un ohonom yn y gwaith. A byddech chi'n mynd i mewn ar fore Mercher ... a byddai disgwyl i chi fynd drwodd, cymathu, trefnu a gweithredu o fewn, yn eithaf aml, 24 awr neu lai. Roedd yn amhosibl.”

- Meddyg Teulu |

| “ | Mae'n debyg bod gen i tua 20 o ganllawiau gwahanol ar gyfartaledd i'w darllen yn ddyddiol yn y gwaith. Ar ddiwedd y dydd, roeddem yn canolbwyntio mwy ar ddarllen y canllawiau hyn nag yr oeddem ar weithredu dros ein cleifion mewn gwirionedd. Cymerodd lawer o amser clinigol gwerthfawr a phrofiad y claf.”

– nyrs meddyg teulu |

Dywedodd rhai cyfranwyr sy'n gweithio ym maes gofal sylfaenol eu bod yn gwneud defnydd o sefydliadau neu unigolion a ddaeth â gwybodaeth berthnasol ynghyd mewn un lle ar gyfer meddygon teulu. Roedd hyn yn eu helpu i ymdopi â’r newid cyson a’r ansicrwydd, ac yn golygu eu bod yn teimlo’n fwy hyderus ynghylch cadw’r cyhoedd yn ddiogel.

| “ | Dechreuodd [Yr Ymddiriedolaeth GIG leol] wneud cylchlythyr a oedd yn crynhoi’r holl e-byst gwahanol i lawr…felly roedd yn golygu y gallem fynd i’r cylchlythyr a chael gwybodaeth gryno… Pe bai hynny wedi dechrau [yn gynharach], efallai na fyddwn wedi fy llethu neu’n poeni cymaint fy mod wedi colli rhywbeth.”

– rheolwr practis meddyg teulu |

| “ | Yn amlwg, cawsom e-byst gan yr awdurdod iechyd ynghylch pa PPE yr oedd yn rhaid i ni ei wisgo a phethau felly ar gyfer rhai gweithdrefnau... hefyd mae gennym uwch ymarferydd nyrsio a oedd yn arfer cydlynu pethau'n eithaf da. Rwy'n credu iddo gael ei gyfleu'n eithaf da. Rwy'n credu nad oedd y cyfathrebu'n ddrwg.”

– nyrs meddyg teulu |

Newidiadau i wasanaethau gofal sylfaenol

Rhannodd cyfranwyr sut yng nghamau cynnar y pandemig Symudodd gwasanaethau meddygon teulu i gyflenwi o bell i leihau'r risgiau o ledaenu Covid-19. Roedd hyn yn golygu bod cleifion - o leiaf ar y dechrau - fel arfer yn cael eu cyfyngu i ymgynghoriadau ar-lein a thros y ffôn.

Wrth i'r pandemig fynd rhagddo, Parhaodd meddygon teulu i addasu a darparu mwy o wasanaethau wyneb yn wyneb lle bo modd. Dywedodd rhai wrthym fod y mesurau sydd eu hangen ar gyfer rheoli heintiau yn golygu ei bod yn amhosibl hyd yn oed yn ddiweddarach yn y pandemig i gynnig yr un mynediad i wasanaethau i gleifion â chyn-bandemig.

| “ | Roedd yn rhaid archebu lle, roedd yn rhaid iddynt hefyd gael eu tymheredd wedi'i wirio a'r math hwnnw o beth, nid oedd mynediad at wasanaethau cystal, yn sicr. Oedd, roedd hyfforddiant cynllunio at argyfwng a pharhad busnes, ond nid wyf yn gwybod bod unrhyw un yn gwybod beth yr oeddent yn delio ag ef.”

– rheolwr practis meddyg teulu |

Roedd practisau meddygon teulu a oedd wedi sefydlu ffyrdd o weithio o bell a brysbennu cleifion dros y ffôn cyn y pandemig mewn sefyllfa well i ymateb. Nid oedd gan bractisau meddygon teulu eraill y systemau hyn ar waith ac roedd yn rhaid iddynt ddod o hyd i ffyrdd dros dro o symud i weithio o bell ar ddechrau'r pandemig.

| “ | Roedd y rhan fwyaf o bractisau’n gweithio systemau apwyntiadau syml…roedd yn rhaid i feddygon teulu eraill sefydlu’r system yr oeddem wedi bod yn ei rhedeg ers tair blynedd dros nos.”

- Meddyg Teulu |

| “ | Roedd rhai achosion pan nad oedd pobl erioed wedi meddwl y byddai angen iddynt weithio gartref ... roedd yn rhaid iddynt ddod i'r maes parcio lle gallent gael derbyniad gan Wi-Fi y GIG ac roeddent yn gallu mewngofnodi ar y gliniaduron oherwydd eich bod chi methu mynd â'ch gliniadur gartref a mewngofnodi.”

- Meddyg Teulu |

Adlewyrchiad cyffredin ymhlith y rhai sy’n gweithio ym maes gofal sylfaenol oedd pwysigrwydd rhwydweithiau anffurfiol i gefnogi’r ymateb pandemig. Datblygwyd y rhwydweithiau hyn i fynd i'r afael â heriau niferus darparu gofal i gymunedau lleol. Roedd cyfranwyr sy’n gweithio ym maes gofal sylfaenol yn aml yn ymuno â grwpiau WhatsApp a Facebook lle gallent rannu gwybodaeth a chyngor ag eraill a oedd yn gwneud newidiadau tebyg i ddarparu gofal. Roedd y grwpiau hyn yn gweithredu fel ffynonellau cymorth pan oeddent yn gweld eu gwaith yn heriol neu'n ansicr ynghylch y ffordd orau o addasu gwasanaethau.

| “ | Rydyn ni i gyd yn ceisio dehongli'r un wybodaeth, a phan fydd manylebau'n agored i'w dehongli, mae hynny'n broblem ... roedden ni'n gallu gwneud trwy grwpiau WhatsApp a sefydlwyd gennym ni fel y gallem ofyn cwestiynau i'n gilydd a rhannu'r wybodaeth honno.”

– rheolwr practis meddyg teulu |

Stori AlaraMae Alara yn feddyg teulu sy'n gweithio mewn practis trefol prysur lle roedd cleifion yn aml yn galw heibio pan oedd angen apwyntiad arnynt neu i godi presgripsiynau. Newidiodd hyn i gyd ar ddechrau'r pandemig. “Yn sydyn, roedd y ganolfan med, a oedd yn gyfleus iawn ac yn hawdd iawn i alw heibio iddi, ar gau. Roedd y cyfan yn hysbysiadau mawr ar y drws a phopeth dros y ffôn. Ac roedd yn rhaid i ni addasu’n gyflym i ffordd newydd o weithio.” Gan weithio gyda phractisau lleol eraill, datblygodd practis Alara borth ymgynghori ar-lein, lle gallai cleifion gyflwyno a lanlwytho ffotograffau yn ogystal ag ateb y cwestiynau gosod. Yna gwelwyd cleifion trwy ymgynghoriadau ffôn. “Roedd y trothwy ar gyfer gweld rhywun wyneb yn wyneb yn llawer, llawer uwch, a chafodd unrhyw un a oedd yn dod ei sgrinio wrth iddynt gyrraedd a chymerwyd eu tymheredd. A phob cyswllt â chlaf, byddem yn rhoi PPE lefel 2 ymlaen, heblaw am yr amser pan oeddem yn gweithio yn y canolfannau Covid-19, lle’r oedd gennym gleifion â symptomau Covid-19 posibl, PPE lefel 3, ac roedd yn teimlo ei fod yn llawer. amgylchedd mwy diogel.” |

Ymunodd rhai cyfranwyr hefyd â gweminarau a chyfarfodydd rhithwir gyda chydweithwyr o wasanaethau gofal iechyd eraill. Roedd hyn yn caniatáu iddynt drafod newidiadau i wasanaethau a gweithio allan sut olwg fyddai ar wahanol ddulliau. Roedd y sesiynau hyn yn caniatáu i syniadau gael eu rhannu'n gyflym ac yn helpu practisau meddygon teulu i addasu.

Dywedodd rhai practisau meddygon teulu wrthym eu bod yn cynnig ymgynghoriadau wyneb yn wyneb cymaint â phosibl. Roedd hyn yn aml yn golygu symud i apwyntiadau a drefnwyd ymlaen llaw i reoli nifer y cleifion a lleihau risgiau heintiau. Disgrifiodd rhai sut y maent yn sefydlu 'ystafelloedd ymateb brys' gyda PPE gradd uwch yn hygyrch i staff, gan ganiatáu i gleifion â symptomau Covid-19 gael eu trin ar unwaith. Newidiodd meddygon teulu eraill y mathau o ofal yr oeddent yn ei gynnig i gleifion mewn ymateb i ofnau cleifion o fynd i'r ysbyty.

| “ | Roeddwn i a meddyg teulu arall yn cymryd y rhan fwyaf o'r risg drwy weld 10% o cleifion wyneb yn wyneb a'r gweddill dros y ffôn. Roedd hi hefyd ymweld â chleifion yn llawer amlach, yn enwedig yr henoed i ddarparu gwrthfiotig IVs nad oedd eisiau mynd i'r ysbyty.”

- Meddyg Teulu |

Roedd y fferyllwyr cymunedol y clywsom ganddynt yn adlewyrchu sut yr oedd pobl yn troi atynt am gymorth pan nad oeddent yn gallu cysylltu â’u meddyg teulu neu wasanaethau gofal iechyd eraill. Roedd hyn yn golygu bod rhai fferyllfeydd cymunedol wedi’u gorlethu â chleifion yr oedd angen cymorth arnynt, gyda chiwiau hir a llawer mwy o alwadau ffôn nag yr oeddent yn arfer â chyn y pandemig.

| “ | Gan fod meddygon yn cau i lawr, o, fy Nuw, daeth yn hysteria. Cawsom ddyddiau [lle] roedd 80 neu 90 o bobl yn ciwio [tu allan i’r fferyllfa].”

– Fferyllydd cymunedol |

| “ | Mae'r galwadau ffôn, lle'r oeddem yn arfer cael, dyweder, 50 o alwadau ffôn mewn diwrnod, cynyddodd y galwadau ffôn i 150. Ni ddaeth y ffôn i ben. Mae un [o’n] fferyllfeydd wedi’i lleoli mewn canolfan feddygol, ond roeddem yn dal i weithredu felly daeth llawer o bobl atom yn lle hynny.”

– Fferyllydd cymunedol |

Dywedodd rhai fferyllwyr wrthym eu bod hwythau hefyd wedi’i llethu gan y galw am ddosbarthu meddyginiaethau i gartrefi pobl yn ystod y pandemig, gan greu pwysau ychwanegol sylweddol. Roedd rhai’n cael eu cefnogi gan eu hawdurdod lleol neu wirfoddolwyr i gadw i fyny â’r galw. Rhannodd llawer sut mae ganddyn nhw fwy o ddanfoniadau o hyd nawr nag oedd cyn y pandemig.

| “ | Cyn i ni gael 10 danfoniad y dydd. Cynyddodd y danfoniadau o hynny i 50-60 danfoniad y dydd. Fe wnaeth y cyngor helpu, ac roedd yna dri neu bedwar o bobl ddosbarthu oedd yn arfer dod, a gwirfoddolwyr oedd eisiau helpu… [Mae danfoniadau] dal i fyny, ac rydyn ni nawr yn cadw gyrrwr.”

– Fferyllydd cymunedol |

Barn cleifion ar y newidiadau i wasanaethau gofal sylfaenol

Roedd cleifion yn gefnogol ar y cyfan ac yn deall y newidiadau i ofal sylfaenol yn ystod y pandemig ac roeddent yn ymwybodol o'r pwysau oedd ar feddygon teulu. Yr oedd cyfranwyr hefyd yn werthfawrogol iawn o wasanaethau fferylliaeth gymunedol, a’r ymdrechion a wneir i gyflenwi meddyginiaethau.

Fodd bynnag, roedd llawer o gleifion yn rhwystredig, yn enwedig ynghylch pa mor hir y bu'n rhaid iddynt aros am apwyntiadau meddyg teulu. Roedd y cyfranwyr hyn yn dadlau nad oedd cau meddygfeydd meddygon teulu yn gwneud synnwyr pan oedd angen enfawr am eu gwasanaethau. Clywsom lawer o enghreifftiau o fethu â chael mynediad at y gofal yr oedd ei angen arnynt, a oedd yn aml yn eu gwneud yn bryderus ac yn siomedig.

| “ | Roedd bron yn teimlo fel cadw pobl i ffwrdd o’r arferion, dull ‘cael ymlaen â’r peth’ yn hytrach na dull cynorthwyol, nad wyf yn eu beio amdano oherwydd mae’n rhaid ei fod wedi bod yn ofnadwy.”

– claf meddyg teulu |

| “ | Roedd yn anodd siarad â meddyg teulu, hyd yn oed ar y ffôn yn delio â materion anadlol, i ddechrau a thros y 2 flynedd gyntaf.”

– claf meddyg teulu |

| “ | Nid oedd angen cau'r practisau meddygon teulu a lleihau hynny. Rwy'n meddwl y gallai llawer o bobl fod wedi cael eu gweld o hyd, pobl sydd â lympiau a thwmpathau neu sydd angen tynnu pethau. Rwy’n meddwl y gallent fod wedi delio â hynny. Rwy’n meddwl efallai y gallai hynny fod wedi achub ychydig o fywydau hefyd.”

– claf meddyg teulu |

Dywedodd llawer o gleifion hefyd eu bod yn falch iawn pan gynigiwyd ymgynghoriadau wyneb yn wyneb eto, yn enwedig ar gyfer cleifion hŷn. Fodd bynnag, teimlai rhai fod y mesurau diogelwch Covid-19 a ddefnyddiwyd wedi achosi problemau eraill, gan ddisgrifio cleifion yn aros y tu allan neu’n cael asesiadau yn yr awyr agored.

| “ | Yn wreiddiol, gwrthodwyd i mi gael fy ngweld gan fy meddyg teulu a’r unig ffordd yr aseswyd fy nghyflwr oedd fy anfon i faes parcio’r feddygfa lle mae nyrs yn cynnal yr archwiliad o weld y cyhoedd yn cerdded heibio.”

– claf meddyg teulu |

Maes arall a oedd yn peri rhwystredigaeth i lawer o gyfranwyr oedd faint o’r newidiadau i ofal sylfaenol a wnaed yn ystod y pandemig ymddangos yn barhaol.

| “ | Mae apwyntiadau meddygon teulu wedi’u newid am byth – nawr rydyn ni’n cael galwad ffôn neu ymgynghoriad fideo yn hytrach na chael ein harchwilio’n bersonol.”

– claf meddyg teulu |

Heriau ymgynghoriadau o bell

Myfyriodd cleifion a chlinigwyr ar yr heriau a’r pryderon sylweddol roedd ganddynt gyda phractisau meddygon teulu yn cau ac yn symud i apwyntiadau o bell. Rhannodd rhai cleifion pa mor ddefnyddiol oedd apwyntiadau o bell yn ystod y pandemig, gan mai nhw yn aml oedd yr unig fath o gyngor a chymorth y gallent gael mynediad ato. Fodd bynnag, roedd llawer o rai eraill yn anhapus fel nad oeddent wedi'u hargyhoeddi y gallai eu symptomau gael eu hasesu'n iawn oni bai eu bod yn gweld rhywun yn bersonol.

Dywedodd rhai wrthym hefyd eu bod yn ei chael yn anodd disgrifio eu symptomau dros y ffôn neu ar-lein. Ar draws y straeon a rannwyd gyda ni, roedd llawer o enghreifftiau o problemau difrifol yn cael eu methu yn ystod ymgynghoriadau o bell, yn aml gyda chanlyniadau difrifol i iechyd pobl.

| “ | Roedd oedi wrth symud canser y croen gan fy modryb ac roedd yn ofnus iawn. Gwnaeth y meddyg teulu apwyntiad ffôn a gwnaeth ddyfarniad nad oedd yn ddim byd difrifol trwy edrych ar lun. Roedd yn anghywir.”

– claf meddyg teulu |

Roedd llawer o gyfranwyr yn bryderus iawn am berthnasau hŷn yn cael eu cyfeirio at wasanaethau ar-lein neu dros y ffôn. Disgrifiwyd yr heriau difrifol a wynebwyd gan eu perthnasau.

| “ | Yn ystod y cloi cyntaf yn 2020 roedd y fam (75 oed) yn cael anawsterau anadlu. Daeth yn rhwystredig gyda'i meddyg teulu oherwydd y diffyg apwyntiadau wyneb yn wyneb. Dros nifer o fisoedd cafodd apwyntiadau ffôn a rhagnodwyd amryw o wahanol anadlyddion a steroidau ar gyfer asthma nad oedd yn gweithio. Teimlai pe bai'r meddyg yn ei gweld yn bersonol ac yn gwrando ar ei brest y byddai'n helpu i ganfod y ... yn lle gwaith dyfalu aneffeithiol. Gwaethygodd ei hanadlu yn gynyddol tan un diwrnod, yn gynnar yn 2021, nid oedd gan fy nhad unrhyw opsiwn ond ffonio 999 a chafodd ei chludo i’r ysbyty.”

- Aelod o deulu'r claf |

Stori AnnaYn ystod y cyfnod cloi, dechreuodd mam-gu Anna ddangos arwyddion cynnar o ddementia. Roedd ei phractis meddyg teulu lleol wedi symud i wasanaethau o bell ac, ar ôl sawl ymgais i sicrhau apwyntiad, cynigiwyd asesiad ffôn. Er bod Anna'n teimlo nad oedd hyn yn ddelfrydol, roedd hi'n ddiolchgar y byddai'r apwyntiad yr wythnos ganlynol. Yn anffodus, ychydig cyn yr apwyntiad, profodd Anna’n bositif am Covid-19 a bu’n rhaid iddi ynysu gartref. Roedd hyn yn golygu na allai fynychu apwyntiad ei nain gyda hi. Wedi hynny, galwodd Anna ei nain i ofyn sut aeth pethau a beth ddywedodd y meddyg teulu. Nid oedd ei nain yn gallu cofio'r hyn a ofynnwyd iddi na'r hyn a ddywedwyd wrthi - ac nid oedd Anna'n gallu darganfod. “Daeth hwn yn gyfnod llawn straen a phryder. Gan nad oedd hi'n gallu cofio, fe wnes i ffonio'r feddygfa fy hun i weld a allent roi unrhyw syniad i mi a oedd yn ddementia a beth i'w wneud nesaf. Gwrthodwyd fi ar sail cyfrinachedd cleifion ac ni allwn gael unrhyw wybodaeth.” Roedd nain Anna hefyd yn cael cymorth gan glinig lles i gleifion hŷn, ond daeth y gwasanaeth hwn i ben yn ystod y pandemig. Roedd hyn yn golygu na chafodd ei chyflwr ei fonitro am y rhan fwyaf o'r pandemig. Pan ailddechreuodd y clinig, cafodd ei hasesu gan nyrs a oedd yn adnabod symptomau dementia a'i hatgyfeirio i'r ysbyty i gael sgan ar yr ymennydd, asesiad dementia ac ymgynghoriad. Ar y pwynt hwn cafodd ddiagnosis o'r diwedd fod ganddi Alzheimer's difrifol. “Ni fydd fy mam-gu yn adennill dim o’r cof a’r gallu meddyliol hwnnw a gollodd. Gallai hyn fod wedi'i ohirio pe bai camau'n cael eu cymryd yn yr apwyntiad cychwynnol gyda'r meddyg teulu. Er fy mod yn deall y risgiau a’r rhagofalon yr oedd eu hangen yn ystod y cyfyngiadau symud, rwy’n teimlo bod hwn yn ddiffyg mawr ac wedi costio llawer o niwed i iechyd a pherthynas i fy nain a’n teulu.” |

Roedd symud i ymgynghoriadau o bell yn anodd iawn i bobl f/Byddar a nam ar eu clyw, y rhai nad oeddent yn siarad Saesneg na Saesneg fel ail iaith, y rhai ag anabledd dysgu, a'r rhai ag awtistiaeth. Roeddent yn wynebu problemau yn deall gwybodaeth a chyfathrebu'n effeithiol, a oedd yn rhwystr i gael mynediad at ofal iechyd.

| “ | Nid oedd deall gwybodaeth, bod yn fyddar, methu â chyfathrebu, llawer o bethau ar-lein, a gorfod defnyddio Saesneg ac ysgrifennu, wyddoch chi, e-byst a phethau felly a negeseuon testun yn hygyrch iawn i mi.”

– d/person Byddar |

Roedd ymgynghoriadau ffôn yn anhygyrch ar y cyfan, gyda cyfieithwyr ddim ar gael yn aml. O ganlyniad, dywedodd rhai wrthym fod yn rhaid iddynt ddibynnu ar aelodau o'r teulu neu wirfoddolwyr a oedd yn gwybod iaith arwyddion i helpu gyda'r galwadau hyn.

| “ | Fe ddywedon nhw [y meddygon] y bydden nhw'n galw fy nhŷ, ond roeddwn i wedi dweud yn barod, 'Rwy'n fyddar, wyddoch chi, nid wyf yn mynd i allu cymryd galwad ffôn'. Rhaid bod ffordd arall, anfon e-bost ataf, anfon neges destun ataf,' ac fe wnaethant ei anwybyddu. Fe wnaethon nhw ffonio fy nhŷ a dweud, 'O, mae hwn yn argyfwng, mae angen ichi fynd i'r adran damweiniau ac achosion brys'. Yn ystod yr alwad ffôn gyntaf roeddwn wedi eu ffonio trwy wasanaeth cyfieithu, ond nid oeddent wedi fy ffonio yn ôl trwy'r gwasanaeth cyfieithu ar y pryd.”

– d/person Byddar |

Roedd ymgynghoriadau ffôn hefyd yn heriol i gyfranwyr nad oedd yn siarad Saesneg fel eu hiaith gyntaf. Roedd yn well gan lawer gael cyfarfodydd wyneb yn wyneb oherwydd gallent ddefnyddio cyfieithwyr yn haws.

| “ | Mae wyneb yn wyneb yn dda, dim ffôn, na, dydw i ddim yn hoffi'r ffôn. Gan fod wyneb yn wyneb yn dda ar gyfer hyder, mae gen i fwy o hyder, mwy o siarad. Beth yw'r broblem? Mae’n dda wyneb yn wyneb a dod â chyfieithydd ar y pryd.”

- Ffoadur |

Clywsom fod rhai pobl awtistig yn teimlo bod y newid sydyn i ymgynghoriadau ffôn yn anghyfforddus ac yn ofidus. Cawsant eu defnyddio ag ymgynghoriadau wyneb yn wyneb, ac roedd natur amhersonol apwyntiadau ffôn yn aflonyddgar iawn.

| “ | Roedd yn rhaid iddo fod mor gyfarwydd â'r aelod hwnnw o staff. Nid oedd yn hoffi newid. Ac roedd fy mab arall yr un peth, ac maen nhw'n dal i fod. Ond roedden nhw'n arfer rhoi rhifau allan i chi eu ffonio, fel y byddai gennych chi rywun i siarad â nhw. Ac roeddwn fel, 'Ni allwch wneud hynny pan fyddant yn awtistig.' Mae'n rhaid i chi gadw at y bobl maen nhw'n eu hadnabod oherwydd maen nhw'n teimlo'n gyfforddus."

– Rhiant person Awtistig |