A report by The Rt Hon the Baroness Hallett DBE

Chair of the UK Covid-19 Inquiry

Volume II: Key themes, lessons and recommendations

Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 26 of the Inquiries Act 2005

Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 20 November 2025

HC 1436-II

| Figure | Description |

|---|---|

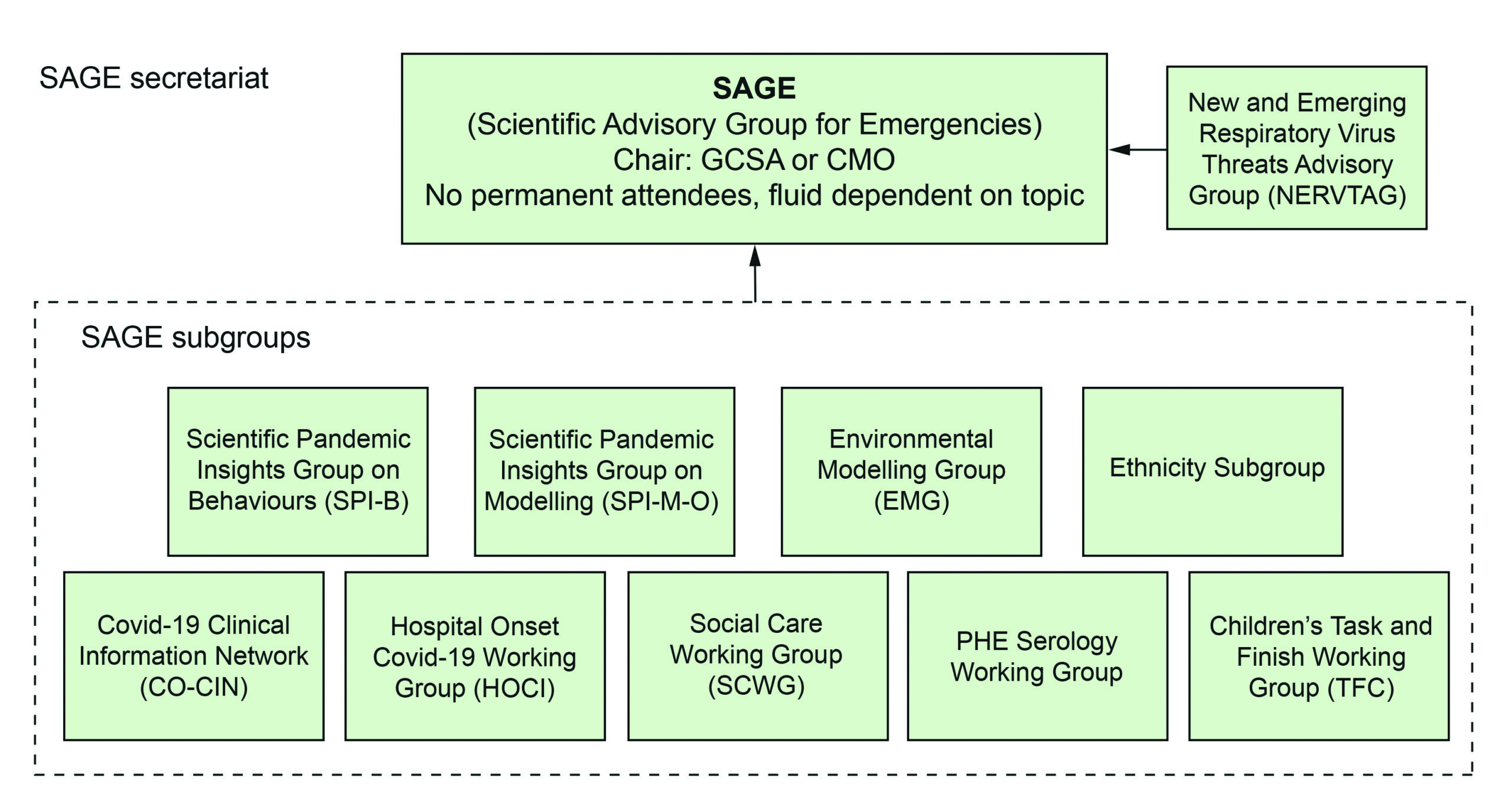

| Figure 39 | Organogram showing SAGE and its sub-groups |

| Figure 40 | ‘Stay Home, Protect the NHS, Save Lives’, 30 April 2020 |

| Figure 41 | ‘Stay Alert, Control the Virus, Save Lives’, 17 July 2020 |

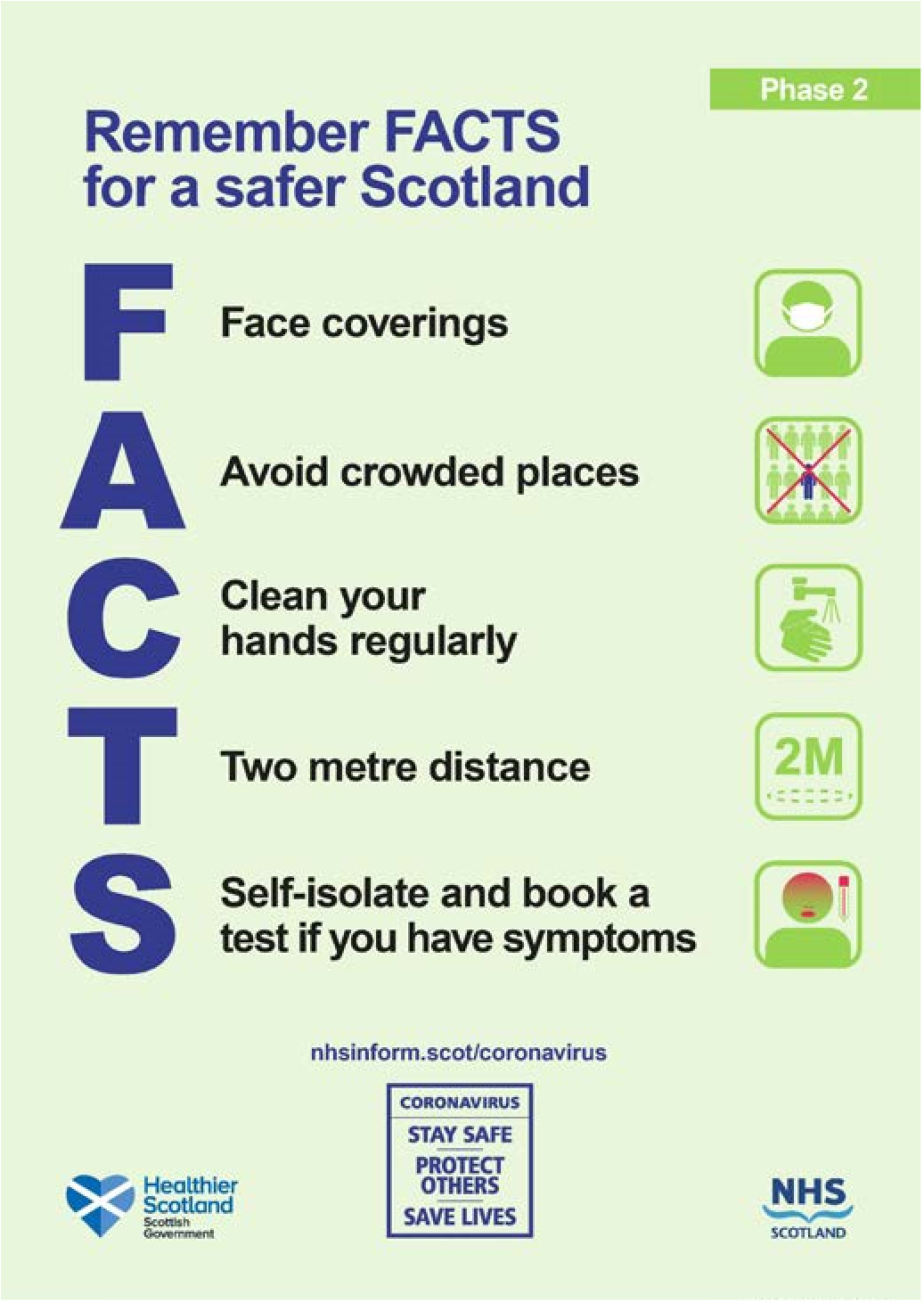

| Figure 42 | FACTS infographic, June 2020 |

| Figure 43 | ‘Hands, Face, Space’, September 2020 |

| Figure 44 | ‘Hands, Face, Space, Fresh Air’, March 2021 |

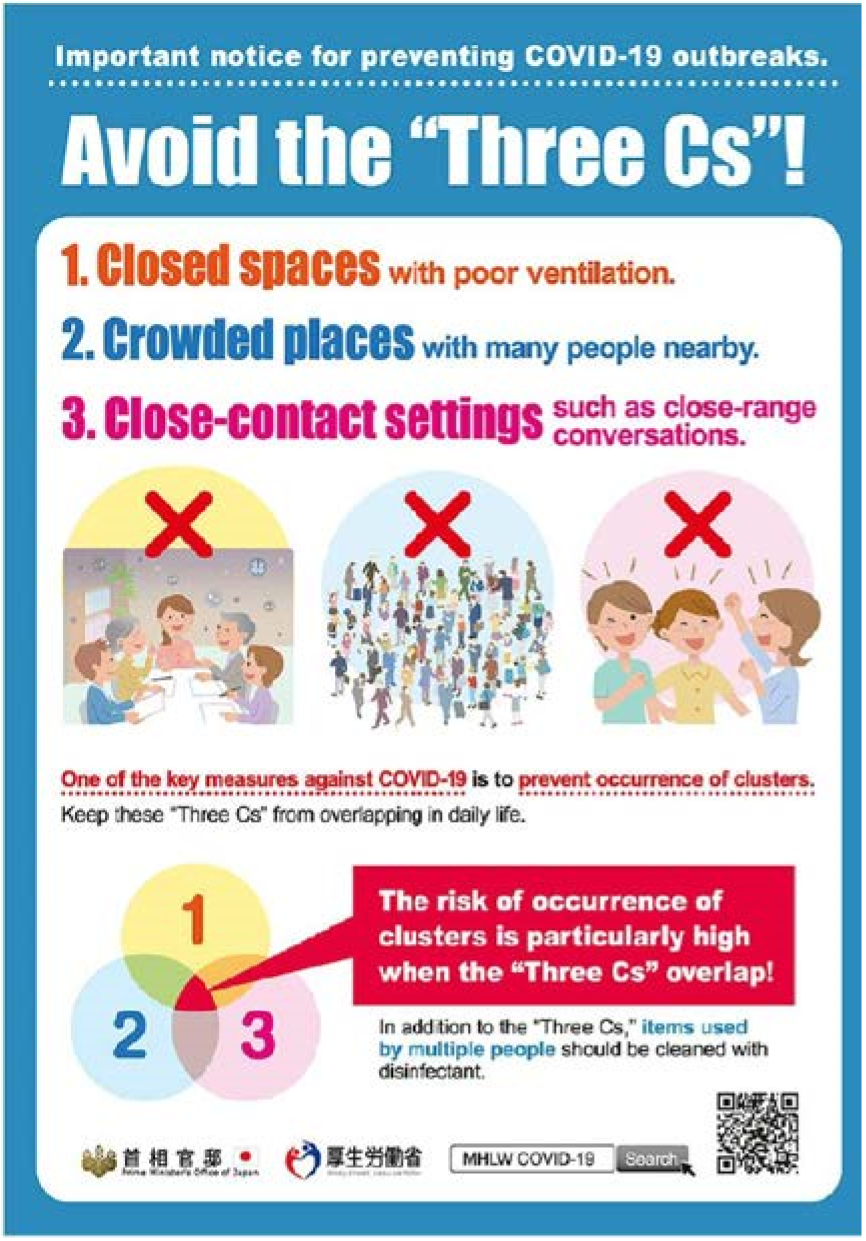

| Figure 45 | ‘Avoid the Three Cs’ |

| Table | Description |

|---|---|

| Table 5 | Summary of penalties across the four jurisdictions at the start of lockdowns in March 2020 and January 2021 |

| Table 6 | Module 2 Core Participants |

| Table 7 | Module 2A Core Participants |

| Table 8 | Module 2B Core Participants |

| Table 9 | Module 2C Core Participants |

| Table 10 | Summary of evidence requested and obtained in Modules 2, 2A, 2B and 2C |

| Table 11 | Expert witnesses |

| Table 12 | Modules 2A, 2B and 2C additional expert witnesses |

| Table 13 | Module 2 witnesses from whom the Inquiry heard evidence |

| Table 14 | Module 2A witnesses from whom the Inquiry heard evidence |

| Table 15 | Module 2B witnesses from whom the Inquiry heard evidence |

| Table 16 | Module 2C witnesses from whom the Inquiry heard evidence |

| Table 17 | Modules 2, 2A, 2B and 2C Counsel teams |

Voices

Five days after Daddy went into hospital we had to get the police to break into my mum’s house because she was unconscious in bed. She was rushed to the same hospital and she would test positive when she got there. My dad died on the 10th of May. The day we buried Daddy, we were waiting for a phone call because that was the day they thought Mummy was going to die. But she died the next day. So we buried them three days apart.”¹

I feel that my mother was getting more and more nervous going into the second lockdown. I feel the Government were on TV every day talking about all these different things and there was no equality for her as an elderly lady. The elderly were not considered. It was a case of ‘keep away from the elderly and vulnerable to protect them’ meanwhile other people were in and out of each other’s bubbles and houses. There was no consideration for the elderly. I feel they were just numbers. My mum caught covid and died in the hospital.”²

[My mother] said ‘No I’m too afraid to go to the hospital, you know, if i haven’t got it and it’s just a really, really bad flu, then I’m going to end up with it, I don’t want to be on my own’ she said. So she was too afraid to go to the hospital.”³

I think I immediately found it very difficult to grieve. Not in the traditional sense, in terms of the funeral, obviously that was not available to us but I found it very hard emotionally to feel the – to go through the natural emotional process of grieving, because I think what was blocking me was that I felt very strongly that his death was not an inevitability.”⁴

Chapter 9: Scientific and technical advice

Introduction

| 9.1. | Throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, decision-makers were fortunate to have at their disposal the expertise and advice of scientists and other experts, many of whom were world leaders in their fields. These scientists and advisers worked extremely long hours and under extraordinary pressure – more often than not unpaid – to provide advice to ministers on how to respond to the virus. They have been criticised by some who disagree with the advice they tendered. That is understandable and perfectly acceptable. Opinions will obviously differ. However, it is not acceptable to launch personal attacks, abuse and threats. The scientists and experts who offered their services to the UK government and devolved administrations during the pandemic deserve the unreserved thanks of the whole of the UK for doing their very best to protect the public in a crisis. |

| 9.2. | This chapter examines the effectiveness of the advice mechanisms in place across the UK during the pandemic. It considers how advice was generated and communicated to ministers, whether it was subject to adequate scrutiny and challenge, and the extent to which it was properly understood and utilised during the response. |

Scientific advice

| 9.3. | There were a number of key scientific advisory personnel and groups that played a central part in the response to the pandemic. |

Key individuals

Chief Scientific Advisers

| 9.4. | The Government Chief Scientific Adviser is a permanent secretary-level post that reports directly to the UK government’s Cabinet Secretary and is a UK-wide role.1 The office holder is responsible for:

“providing scientific advice to the Prime Minister and members of the Cabinet, advising the government on aspects of science for policy and improving the quality and use of scientific evidence and advice in government”.2 |

| 9.5. | The Government Chief Scientific Adviser is supported by the Government Office for Science (also known as GO-Science), an office of the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology.3 From April 2018 to March 2023, the Government Chief Scientific Adviser was Professor Sir Patrick Vallance (later Lord Vallance of Balham), a clinical academic with a background in medicine and pharmacology.4 Professor Vallance explained that his role was “primarily about providing science advice to policy makers, rather than advising on science policy itself“.5 |

| 9.6. | The majority of UK government departments also employ a departmental Chief Scientific Adviser who provides scientific advice within the department and across government.6 The departmental Chief Scientific Advisers were involved in various aspects of the Covid-19 response, including holding roles on the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) and its sub-groups and providing support to both the Government Chief Scientific Adviser and the Chief Medical Officer for England (discussed below). The Chief Scientific Adviser at the Department of Health and Social Care is also the head of the National Institute for Health and Care Research. |

| 9.7. | The devolved administrations adopted different structures for their scientific advisers.7 |

| 9.8. | The Chief Scientific Adviser for Scotland is responsible for sourcing and providing advice in response to requests from the Scottish Government.8 It is a part-time role, with the holder typically seconded from academia. The post was held by Professor Sheila Rowan from June 2016 to June 2021, followed by Professor Julie Fitzpatrick.9 |

| 9.9. | In addition, the Chief Scientist (Health) for the Scottish Government reported to the Chief Medical Officer for Scotland, who was Dr Catherine Calderwood from April 2015 to April 2020. Professor David Crossman held the position of Chief Scientist (Health) for the Scottish Government from November 2017 to April 2022. However, he played no role in the pandemic response until March 2020, when he was invited to develop a testing strategy in Scotland and was appointed Vice Chair of the Scottish Government Covid-19 Advisory Group.10 Professor Crossman observed:

“During the pandemic it was not entirely clear how the Scottish Government wanted to use its Chief Scientific Adviser and CSH [Chief Scientist (Health)]. Certainly, there were times where I was uncertain where I fitted into the structures which provided advice to Scottish Government.”11 Professor Crossman’s limited early involvement in the pandemic response and his evidence that he did not know if he “would have had much traction” had he attempted to be more vocal in raising his concerns demonstrated a lack of engagement by Dr Calderwood with a senior scientific adviser to the Scottish Government at the beginning of the pandemic.12 |

| 9.10. | Professor Peter Halligan was the Chief Scientific Adviser for Wales from March 2018 to February 2022.13 However, it was Dr Rob Orford, Chief Scientific Adviser (Health) from January 2017, who led the Welsh Government’s scientific efforts during the pandemic.14 Dr Andrew Goodall (Director General of Health and Social Services in the Welsh Government and Chief Executive of NHS Wales from June 2014 to November 2021, Permanent Secretary to the Welsh Government from September 2021) emphasised the need to formally recognise the Chief Scientific Adviser (Health) for Wales in the UK’s preparedness and response systems.15 This lack of clarity in the roles and responsibilities of the Chief Scientific Adviser for Wales and the Chief Scientific Adviser (Health) for Wales likely contributed to the UK government’s assumption that Professor Halligan should represent Wales at SAGE.16 |

| 9.11. | In Northern Ireland, there was no cross-government chief scientific adviser. Instead, there were two departmental Chief Scientific Advisers. One of these was Professor Ian Young, Chief Scientific Adviser to the Department of Health (Northern Ireland) from November 2015.17 Prior to the pandemic, this was a part-time role. During the Covid-19 response it became equivalent to a full-time role, albeit that Professor Young continued to do clinical work and also “some academic work at times”.18 He confirmed that his “remit in relation to the pandemic was not recorded or specified in writing at the outset but evolved during the pandemic”.19 |

| 9.12. | This lack of clarity in roles did not exist in the UK government. The devolved administrations should consider providing greater clarity as to the specific roles and responsibilities of their Chief Scientific Advisers and Chief Scientific Advisers for Health within pandemic planning to avoid similar confusion at the outset of any future emergency. |

Chief Medical Officers

| 9.13. | The Chief Medical Officer for England is the UK government’s principal medical adviser. They provide public health and clinical advice to ministers in the Department of Health and Social Care, the Prime Minister, other ministers and senior officials across government in England.20 Since October 2019, the post has been held by Professor Sir Christopher Whitty, an epidemiologist and physician specialising in infectious diseases.21 |

| 9.14. | During the pandemic, Professor Whitty was supported by three Deputy Chief Medical Officers for England.22 Professor Whitty told the Inquiry that he and the Deputy Chief Medical Officers had “considerable mutual trust in one another’s judgement”.23 He also “spoke several times each day” with Professor Vallance, whom he described as “exceptionally level headed and collegiate”.24 Professor Vallance stated that he felt “extremely fortunate” to work with Professor Whitty, with whom he felt “able to discuss everything”.25 Both said that they were aligned in their advice on the vast majority of occasions and that they were able to explain the reasons for any disagreements to decision-makers.26 Boris Johnson MP, Prime Minister from July 2019 to September 2022, remarked that Professors Vallance and Whitty:

“did an excellent job of presenting the science in a way that was most useful to political decision-makers”.27 |

| 9.15. | Under the devolution settlements, health is a devolved responsibility.28 Each devolved administration therefore has its own Chief Medical Officer. |

| 9.16. | During a public health emergency in Scotland, the Chief Medical Officer for Scotland’s role is akin to those of both the Chief Medical Officer for England and the Government Chief Scientific Adviser. They are the most senior adviser to the Scottish Government on health matters and the main translator of scientific information and debate for decision-makers.29 Dr Calderwood resigned in April 2020 and was succeeded on an interim basis by Professor (later Sir) Gregor Smith, who had been Deputy Chief Medical Officer for Scotland from April 2015.30 Professor Smith was confirmed in the post permanently in December 2020. |

| 9.17. | Dr (later Sir) Frank Atherton was Chief Medical Officer for Wales from August 2016.31 Although he was a Welsh Government staff member, he told the Inquiry that he operated with a high degree of independence and was able to offer guidance without being constrained by government policy or direction.32 He told the Inquiry that his advice to the Welsh Cabinet was based on a range of sources, including SAGE outputs and information from the Joint Biosecurity Centre, the Welsh Government’s Knowledge and Analytical Services, the Chief Economic Adviser in Wales and the Technical Advisory Group/Technical Advisory Cell.33 From March 2020, he regularly attended Welsh Cabinet meetings to give oral updates and advice, in addition to providing written advisory notes, which began to be published from May 2020 and were incorporated into Cabinet papers.34 He emphasised the trust and collaboration he had with his colleagues, especially Dr Orford.35 |

| 9.18. | Professor Sir Michael McBride has been the Chief Medical Officer for Northern Ireland since September 2006. During the pandemic, he was an official within the Department of Health (Northern Ireland) and, as a member of the department’s senior management team and departmental board, was part of its management structure.36 Prior to the pandemic, he had concurrently held the offices of Permanent Secretary to the Department of Health (Northern Ireland) and Chief Medical Officer for Northern Ireland.37 |

| 9.19. | Professor McBride told the Inquiry that he had responsibility for the provision of medical advice and also policy responsibility:

“for all aspects of public health, so that would have included health protection, health improvement. I also had policy responsibility for quality and safety and policy, so as that pertained to, for instance, serious adverse incidences, investigation processes and policy, complaints policy. I also had policy responsibility for research within health and social care … I also had a number of other roles within that, including sponsorship responsibilities on behalf of the department which I exercised in relation to the Public Health Agency.”38 During the pandemic, Professor McBride’s role also extended to the operational aspects of the response.39 He accepted that he was not functionally independent of the Department of Health (Northern Ireland). He told the Inquiry that he was “conscious it almost seems like I’m trying to wear two hats, you know, both at the same time”.40 While he accepted that he was “not independent in terms of policy responsibility”, he emphasised that he was independent in his “professional advisory role”.41 |

| 9.20. | In the context of the pandemic, it is difficult to see how Professor McBride’s roles in a smaller devolved administration could be decoupled from each other in practice or how he could provide advice to the Northern Ireland Executive Committee on the response to the pandemic without that advice being informed by the position and interests of the Department of Health (Northern Ireland). |

| 9.21. | It is also noteworthy that, in the specific context of power-sharing in Northern Ireland, the Department of Health (Northern Ireland), like all Executive departments, operates with a high degree of operational independence. As described throughout this Report, the response to the pandemic was driven by the Department of Health (Northern Ireland) rather than representing a true cross-government effort. The Department of Health (Northern Ireland), including Professor McBride, was at times protective of its centrality to the response and regarded the Northern Ireland Executive Committee as an obstacle to that response.42 It was also perceived as being “in a very powerful position” throughout the pandemic.43 |

| 9.22. | It would have been preferable for the Northern Ireland Executive Committee to have had access to its own source of medical advice which was independent of any government department. This might have helped to produce an earlier cross-government understanding of how the pandemic was likely to develop, adequate planning across government and a more effective cross-government response. |

| 9.23. | Reforming the office of Chief Medical Officer for Northern Ireland so that it is independent of the Department of Health (Northern Ireland) (and of any other Executive department) would enable the Chief Medical Officer for Northern Ireland to provide advice without the risk of being perceived as representing the interests of a single department or minister. It would also ensure that scientific advice is immediately and directly available to the wider Executive Committee. |

Recommendation 1: Chief Medical Officer for Northern Ireland

The Department of Health (Northern Ireland) should reconstitute the role of the Chief Medical Officer for Northern Ireland as an independent advisory role. The Chief Medical Officer for Northern Ireland should not have managerial responsibilities within the Department of Health (Northern Ireland).

| 9.24. | In June 2024, the Northern Ireland Executive established the post of Chief Scientific and Technology Adviser and a Northern Ireland Science and Technology Advisory Network. The Executive Office told the Inquiry that the latter will be chaired by the Chief Scientific and Technology Adviser and will provide a vehicle for delivering collective advice to the Northern Ireland Executive.44 This is a welcome recognition of the need for formal and structured scientific advice across government. |

| 9.25. | Close working relationships between scientific advisers are essential for an effective emergency response. They must be able to debate relevant issues freely, challenge one another and resolve any differences in opinion. The evidence heard by the Inquiry shows that the Chief Scientific Advisers, Chief Medical Officers and their deputies in all four nations of the UK worked exceptionally well together throughout the Covid-19 response. Such strong working relationships must be a feature of any future emergency. |

Scientific advisory groups

The Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies

| 9.26. | SAGE brings together independent research and analysis from a range of experts across government, academia and industry.45 It does not formulate policy or undertake a delivery role, but provides a single source of scientific and technical advice to support decision-makers across the UK in the event of a civil emergency.46 As a UK-wide technical resource, SAGE provides scientific advice that is relevant to all four nations of the UK. It engages on issues of national or regional difference only where there is “a strong technical (e.g. epidemiological) rather than political or operational reason to do so”.47 The exact role it plays is determined by the emergency in question, but its advice is “limited to scientific matters and is a cross-disciplinary consensus view based on available evidence at the time”.48 |

| 9.27. | During the Covid-19 response, SAGE was the primary mechanism through which scientific advice was channelled into government. However, it was not designed for the breadth or duration of the role that it performed during the response.49 Prior to the pandemic, crisis management structures (including SAGE) were typically utilised as “short-term response vehicles” for discrete and short-lived emergencies.50 Between January 2020 and February 2022 – the longest period for which SAGE had been convened since its inception – it met on 105 occasions.51 During that time, more than 350 scientists participated in or contributed to its work.52 |

| 9.28. | SAGE’s first precautionary meeting was convened by Professor Vallance and held on 22 January 2020.53 This and all subsequent meetings were chaired by Professor Vallance. As Covid-19 was a health-related emergency, Professor Whitty acted as Co-Chair for the duration of the response.54 The chairs rapidly assembled a group of experts from key disciplines, including medicine, epidemiology, virology and behavioural science.55 They were also assisted by specialists from across government, including Public Health England and the Office for National Statistics, and by departmental Chief Scientific Advisers.56 SAGE also expanded its structure through the establishment of sub-groups, each of which had its own disciplinary expertise, such as the environment, ethnicity or social care.57 |

| 9.29. | The established system by which SAGE reported to COBR did not, however, continue beyond the first few months of the pandemic. In mid-March 2020, Ministerial Implementation Groups were set up by the UK government. Professor Vallance noted that, for a period between March and May 2020, while scientific advice was “presented directly into regular meetings in No. 10 [10 Downing Street]”, it was “less clear how science advice was feeding into” the Ministerial Implementation Groups.58 The replacement of the Ministerial Implementation Groups with the Covid-19 Strategy Committee (Covid-S), the Covid-19 Operations Committee (Covid-O) and the Covid-19 Taskforce in May 2020 “helped to simplify the structure“.59 Professor Vallance told the Inquiry:

“[I]t narrowed down to a more sensible system, and that then improved quite a lot over time in terms of them being able to ask better questions as well and frame them more appropriately.”60 |

| 9.30. | In future emergencies, a consistent and clear structure and reporting line for SAGE should be established from the outset. As Professor Vallance noted:

“[T]here needs to be a system that swings into action immediately … a structure which will stay constant … properly populated with people who can both look at the operational needs that come out of that, so they can co-ordinate that across Whitehall, and have enough scientific understanding and data analysis understanding to be able to absorb the evidence and understand the implications.”61 |

| 9.31. | Those who attended SAGE meetings did so in the capacity of either ‘participant’ or ‘observer’. Participants were expert government advisers or external scientific advisers. They actively engaged in the debates that took place. Observers were representatives of government departments or agencies and did not contribute to meetings other than to clarify a point or ask a question. However, they were expected to disseminate information to their home organisation.62 This distinction was necessary in order to prevent the number of participants in SAGE from becoming unwieldy, while balancing the need for others to be fully aware of the latest scientific advice. |

Figure 39: Organogram showing SAGE and its sub-groups

Source: INQ000303289

| 9.32. | One of these sub-groups, the Scientific Pandemic Insights Group on Behaviours (SPI-B), had its origins in the Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Behaviour and Communications (SPI-B&C), which was established in response to the 2009 to 2010 H1N1 influenza pandemic (‘swine flu’). SPI-B provided independent, expert, social and behavioural science advice to SAGE. |

| 9.33. | When SPI-B was established in February 2020, the ‘C’ was removed on the basis that communications were considered to be operational matters for government.63 In this respect, there appeared to have been some misunderstanding as to the difference between the behavioural science underpinning communication strategies (which should have remained a matter for SPI-B and SAGE) and the communication itself (which was properly a matter for government). There were also departmental behavioural and communications teams within both the Cabinet Office and 10 Downing Street, including the Cabinet Office Behavioural Insights Team. This, on occasion, resulted in a fragmented approach, a lack of accountability with regard to advice (eg on ‘behavioural fatigue’; see Chapter 4: Realisation and lockdown, in Volume I), under-utilisation of SPI-B and tensions between the various teams. These tensions sometimes spilled into the public domain.64 In future, there should be clarity on the roles to be played by the different bodies. |

| 9.34. | The Inquiry notes that Dame Deirdre Hine’s July 2010 review of the UK response to the swine flu pandemic raised issues concerning SPI-B&C not being used as effectively as it might have been.65 This problem appears to have arisen again. The recommendation from Dame Deirdre Hine bears repetition: relationships ought to be built between the relevant teams to ensure the effective use of SPI-B’s expertise in addition to internal government resources. Similarly, the expertise of SPI-B and government behavioural science teams ought to be drawn upon in pandemic planning. |

| 9.35. | In addition, SAGE drew upon the expertise of two pre-existing expert committees of government departments: the Scientific Pandemic Infections Group on Modelling (SPI-M), which was redeployed as a formal sub-group of SAGE for the duration of the pandemic, and the New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group (NERVTAG), which remained separate from SAGE (see below). Both bodies performed a vital role in the pandemic response and they worked together well. In non-pandemic periods, SPI-M provides expert advice on infectious disease analysis, modelling and epidemiology. In an emergency, SPI-M’s Operational sub-group (SPI-M-O) can be stood up, as happened with the Covid-19 response.66 |

| 9.36. | NERVTAG is an expert committee of the Department of Health and Social Care. It provides independent scientific risk advice to the Chief Medical Officer for England – and, through them, to ministers, the Department of Health and Social Care and other government departments – on the threat posed by new and emerging respiratory viruses and options for their management. Although the Department of Health and Social Care’s protocol indicated that NERVTAG would stand down in an emergency, a decision was taken that it would remain operative to harness its expertise.67 With Professor Sir Peter Horby (Professor of Emerging Infectious Diseases and Global Health at the University of Oxford) as its Chair from May 2018, NERVTAG subsequently took commissions from SAGE, the Department of Health and Social Care and Public Health England. SAGE, however, remained responsible for the coordination of scientific advice, including from NERVTAG.68 |

| 9.37. | Effective communication and collaboration between the advisory groups (whether permanent or ad hoc) are crucial elements in developing interdisciplinary evidence. There were some good examples of collaboration – for instance, in the relationship between NERVTAG and SPI-M-O.69 However, many groups were convened only during emergencies or created during the pandemic. Consequently, relationships had to be built without pre-existing foundations of interdisciplinary knowledge. For example, Professor Graham Medley (Professor of Infectious Disease Modelling at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and Co-Chair of SPI-M-O from January 2020 to February 2022) described links between SPI-B and SPI-M-O as “non-existent initially“.70 Collaboration relied upon individuals within SAGE, NERVTAG and the various sub-groups and committees. |

| 9.38. | The Inquiry was concerned to learn that this issue resurfaced in the 2022 mpox (previously known as monkeypox) outbreak, during which “the modellers, the clinicians and the behavioural experts were somewhat siloed“.71 This is indicative of a systemic issue. To address this, the chairs of these groups should jointly consider and keep under review mechanisms to promote effective collaboration, including creating cross-membership between sub-groups and the sharing of relevant materials. |

| 9.39. | The SAGE mechanism, however, did work well. Under intense and sustained pressure, it provided high-quality scientific advice throughout the Covid-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, while fundamental change is not required, the unprecedented duration and complexity of the Covid-19 pandemic exposed several weaknesses within SAGE’s structure. As discussed further below, these related to the recruitment and selection of its participants, attendance at meetings, the process for commissioning advice, the preparation and communication of advice, and resourcing and pastoral support. |

The devolved administrations’ attendance at SAGE meetings

| 9.40. | The devolved administrations were often represented at SAGE by their Chief Scientific Advisers, Chief Medical Officers or a senior official – some of whom attended as participants and others as observers, depending on their role.72 |

| 9.41. | Dr Jim McMenamin, Head of Infections Service and Strategic Incident Director for Covid-19 at Public Health Scotland, attended SAGE from its first meeting on 22 January 2020.73 Although Professor Halligan was invited on behalf of Wales, he did not attend, as health was not part of his remit.74 Dr Orford contacted the Government Office for Science Secretariat and asked to be provided with the “read-out from the SAGE meeting” and for clarity on the attendance of the devolved administrations.75 On 5 February 2020, he queried why the invitation to SAGE was extended to Professor Halligan only. He considered this to be inadequate from a health standpoint and it was something he had previously queried with Professor Halligan in August 2019.76 It is unfortunate that this had not been clearly resolved by the onset of the pandemic. Professor Halligan’s office should have been more proactive in respect of the first meetings of SAGE. Either a representative from his office should have attended those meetings, or he should have sought permission to send Dr Orford (or a representative) from the outset. On 11 February 2020, Dr Orford attended SAGE as an observer. This was the first time a representative of the Welsh Government attended a SAGE meeting on Covid-19. From 5 March 2020, Dr Orford was formally recognised as a participant.77 |

| 9.42. | The Northern Ireland Executive was not invited to be represented at the first meeting of SAGE. Professor McBride said he attended a number of SAGE meetings as an observer from 7 February 2020 onwards and the Department of Health (Northern Ireland) confirmed that a “trainee medical adviser” observed some of them.78 However, neither the content of the SAGE meetings nor any underlying papers were synthesised for ministers in Northern Ireland. It was not until 27 April 2020, when Professor Young established the Strategic Intelligence Group (see below), that the capacity to produce regular Northern Ireland-specific analyses existed.79 Professor Young was on leave due to illness from 12 February to 23 March 2020.80 Upon his return, he joined SAGE as a full participant and attended meetings from 29 March.81 According to Professor Young, he was keen to emphasise at SAGE that Northern Ireland, “by virtue of geographical separation from [Great Britain,] was a separate epidemiological unit (as part of the island of Ireland)“.82 |

| 9.43. | Professor Vallance confirmed that the devolved administrations were invited to every SAGE meeting from 11 February 2020.83 The meetings were also not the only mechanism by which the devolved administrations engaged with SAGE’s advice. For example, from 24 January 2020 onwards, Professor Whitty met with his counterparts “on a frequent and regular basis”.84 In addition, the devolved administrations were routinely represented at COBR, which was a key channel for sharing scientific advice. |

| 9.44. | It is surprising that representatives from each of the devolved administrations were not invited to attend SAGE from the outset of the pandemic. The processes by which the devolved administrations subsequently secured appropriate representation and gained access to SAGE lacked clarity, which resulted in disparities in access to information that might have informed their decision-making. As Professor Vallance commented, there is:

“a good case to be made for representatives of Devolved Administrations being invited to SAGE discussions that concern their countries from the first meeting”.85 |

| 9.45. | SAGE is not intended to be a geographically representative body.86 It brings together the scientific experts who are best qualified for a specific emergency, regardless of their location. Ensuring that the devolved administrations have access to SAGE must not overwhelm its membership. The Inquiry recommends, therefore, that a small number of representatives from each of the devolved administrations should be invited to attend meetings of SAGE and its sub-groups from the outset of any future emergency. The devolved administrations should be consulted about who is best placed to attend, but SAGE should determine their status as participant or observer. |

Recommendation 2: Attendance of the devolved administrations at SAGE meetings

The Government Office for Science (GO-Science) should invite the governments of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to nominate a small number of representatives to attend meetings of the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) from the outset of any future emergency. The status of those representatives as either ‘participant’ or ‘observer’ should depend upon their expertise and should be a matter for SAGE to determine.

Scientific advisory groups for the devolved nations

| 9.46. | The Inquiry heard that the devolved administrations depended heavily on the scale and breadth of SAGE’s expertise throughout the pandemic, but most particularly in the early months. As the pandemic progressed, the devolved administrations utilised or set up their own advisory scientific committees. These fed information into SAGE while applying its advice to their own local circumstances. |

The Scottish Government Covid-19 Advisory Group

| 9.47. | Although SAGE was a useful source of evidence and scientific consensus from which Dr Calderwood could develop advice for the Scottish Government, Nicola Sturgeon MSP (First Minister of Scotland from November 2014 to March 2023) had two concerns about the operation of SAGE in the initial weeks of the pandemic. The first was that SAGE’s advice was insufficiently tailored to Scottish circumstances. The second was that there was no opportunity for Ms Sturgeon or other Scottish Government ministers to ask questions of SAGE participants directly to better understand the advice.87 For these reasons, she considered it appropriate to establish a Scottish advisory body to interpret and supplement the advice available to the Scottish Government from SAGE. She asked Dr Calderwood to establish such a group, which became the Scottish Government Covid-19 Advisory Group.88 |

| 9.48. | Professor Andrew Morris, Professor of Medicine at the University of Edinburgh, chaired the Scottish Government Covid-19 Advisory Group. Its members were invited to serve by Dr Calderwood, and later by Professor Smith, and they were chosen on the basis of scientific or technical expertise. The group’s membership included public health experts, clinicians, and academics spanning the disciplines of epidemiology, virology, public health, behavioural science, global health, medicine and statistical modelling.89 |

| 9.49. | The Scottish Government Covid-19 Advisory Group met regularly for the first few months and senior decision-makers within the Scottish Government expressed satisfaction with its work. Ms Sturgeon commented:

“[It] was a reliable and effective source of advice, and it worked well – both in terms of the advice it provided directly and through its sub-groups, either on its own initiative or commissioned, and in its reciprocity with SAGE, which enabled advice from the latter to be interpreted for the Scottish context.”90 A principle of reciprocity was agreed between SAGE and the Scottish Government Covid-19 Advisory Group to ensure that the two groups were given access to each other’s papers.91 |

| 9.50. | Although the Scottish Government Covid-19 Advisory Group’s role was akin to that of SAGE, it had fewer resources and a less established presence in government.92 Competing priorities meant that Professor Smith attended just 8 of the 40 meetings in 2020 and others would regularly deputise on his behalf.93 His lack of attendance in person became an issue of concern for members, with the minutes of the meeting on 20 April 2020 recording that Professor Morris “will send Gregor [Professor Smith] an email about the group”.94 Professor Morris accepted that “you could conclude” that:

“in order to engage with that expertise properly or appropriately, it would have been necessary for the CMO [Chief Medical Officer] to have attended the meetings and listened to the views and expert opinions of that wide variety of experts”.95 |

| 9.51. | The Scottish Government also received advice from other organisations, such as Public Health Scotland, the four Chief Medical Officers, Scottish territorial health boards, Scottish local authorities, primary care services, the Scottish business community and the independent care sector.96 This meant that the group often struggled to secure direct access to senior decision-makers. Professor Morris reflected:

“Ideally, the rapid assembly of the C19AG [Scottish Government Covid-19 Advisory Group] would have been part of mature and pre-existing advisory structures, with deep integration across the four nations.”97 |

The Technical Advisory Cell and the Technical Advisory Group (Wales)

| 9.52. | The Technical Advisory Cell and the Technical Advisory Group were central to the Welsh Government’s response to the pandemic, providing crucial scientific advice and expertise to inform key public health decisions. The Technical Advisory Cell, established on 27 February 2020, provided a secretariat, coordination and leadership function for the Technical Advisory Group.98 By the end of March 2020, the Technical Advisory Group was operational as a distinct body, separate from the Technical Advisory Cell and comprised experts from various fields.99 The group’s role was to:

“collate, create and mobilise knowledge related to the pandemic, including Welsh specific information, to support decision making within the Welsh Government by Welsh Ministers”.100 |

| 9.53. | Technical Advisory Group meetings were scheduled to review SAGE’s outputs and interpret them in a Welsh context.101 Dr Orford was appointed Chair to both the cell and the group, due to the health-related nature of the Covid-19 emergency.102 |

| 9.54. | By October 2020, the Technical Advisory Group had established nine sub-groups. All sub-group chairs were members of the main group and, where relevant, a member from each sub-group also participated in the equivalent SAGE sub-group.103 Subject matter experts from Public Health Wales were also members of the Technical Advisory Group and its sub-groups.104 |

| 9.55. | Mark Drakeford MS, First Minister of Wales from December 2018 to March 2024, believed that the work of the Technical Advisory Cell and the Technical Advisory Group was extremely valuable.105 In Chapter 2: The emergence of Covid-19, in Volume I, the Inquiry concludes that the Welsh Government was slow to respond to Covid-19 in January and February 2020. Dr Orford suggested that having a Technical Advisory Cell (or similar structure) in place earlier could have led to a different reaction from January 2020 onwards.106 |

The Strategic Intelligence Group (Northern Ireland)

| 9.56. | On 27 April 2020, Professor Young established the Strategic Intelligence Group in Northern Ireland.107 Prior to that point, there had been no advisory group to consider SAGE papers and output in the Northern Ireland context and specifically for a ministerial audience. Professor Young explained that advice from the Strategic Intelligence Group aligned closely with advice emanating from SAGE, but took account of the circumstances in Northern Ireland, including its cultural and geographical features, the spread of the virus and the response to it throughout the island of Ireland.108 The delay in establishing such a body is symptomatic of a problem described throughout this report: the lack of a coherent, cross-government response in Northern Ireland to the emerging pandemic. Rather, the response was driven by the Department of Health (Northern Ireland) and individuals within it. As a result, Professors Young and McBride had a great deal of control over the flow of information and advice to ministers across government in Northern Ireland. One particularly unfortunate consequence was that the establishment of Northern Ireland-specific scientific advice had to await the return of Professor Young from a period of absence. |

| 9.57. | Professor McBride observed that, “in all small jurisdictions, one of the problems is that you have too many single critical points of failure potentially”. He identified this as a possible point of learning for the future.109 The problem of having so few people in critical positions extends further than potential points of failure – there were very few, if any, individuals capable of providing informed challenge. In this context, Professor Young highlighted the importance of the work of the Strategic Intelligence Group. He considered that it would be desirable to stand up a similar body at an earlier stage during any future pandemic or health emergency to serve a similar function.110 The Inquiry agrees on the need for nation-specific scientific advisory bodies in each of the devolved administrations to advise their respective governments. These structures should be ready to be activated at the outset of any future pandemic. |

The role of public health bodies in providing advice

England

| 9.58. | Public Health England was established in April 2013 as an executive agency of the Department of Health (known from January 2018 as the Department of Health and Social Care). Public Health England provided the infrastructure for health protection in England, including the investigation and management of local and nationwide outbreaks of infectious disease.111 It was effectively abolished by the UK government following the commencement of the pandemic and replaced by the UK Health Security Agency in October 2021.112 The UK Health Security Agency was established to provide the UK’s “permanent standing capacity to prepare for, prevent and respond to infectious diseases and other threats to health”.113 |

| 9.59. | During the Covid-19 response, Public Health England delivered clinical and public health advice to the Chief Medical Officer for England and to government departments.114 It also provided operational support to the Department of Health and Social Care and to the NHS and translated SAGE’s advice into evidence-based guidance for clinical audiences and the public. In addition, Public Health England undertook a range of specific scientific, research and evaluation tasks, including early testing and contact tracing. |

| 9.60. | Significant resource constraints affected Public Health England’s ability to fulfil both its advisory and its operational functions.115 As was common across the four nations, there was, for example, no standing capacity for a scaled-up test and trace system.116 The resource constraints on Public Health England are illustrated by its £287 million budget for 2019/20, compared with the £37 billion allocated to NHS Test and Trace.117 |

| 9.61. | Professor Vallance observed:

“The decisions taken over a number of years to reduce the science budget of PHE [Public Health England] must have had an effect on its ability to perform at scale during the pandemic. The outsourcing of research to universities left PHE with restricted internal science and operational capability … it is important to view public health science funding as a resource that is required for the future, much in the same way as the army is required to be ready for action even when there is no war.”118 |

Scotland

| 9.62. | Health Protection Scotland was part of NHS National Services Scotland. It was responsible for implementing operational decisions made by the Scottish Government, developing guidance arising out of government policies throughout the pandemic and producing detailed statistics and analysis of data in respect of the health service. On 1 April 2020, functions of Health Protection Scotland were transferred to a new body, Public Health Scotland.119 |

| 9.63. | The main avenue for clinical and scientific advice to flow from Public Health Scotland to the Scottish Government was via the Chief Medical Officer for Scotland, either in direct correspondence or communication between advisers and the Chief Medical Officer, or through the National Incident Management Team.120 |

| 9.64. | The National Incident Management Team met for the first time on 13 January 2020 in response to emerging knowledge about the virus. It was a cross-system approach that incorporated health boards, local authorities and the Scottish Government. It met regularly to consider the developing data and evidence in order to allow information and advice to be fed to the Scottish Government. |

| 9.65. | Representatives of Public Health Scotland attended Scottish Government Resilience Room meetings and the Four Harms Group. Prior to such meetings, Public Health Scotland provided statistical information and analysis by way of the regularly updated Situation Reports (SitReps). These reports formed a key aspect of the analysis and assessment of the progress of the pandemic.121 |

| 9.66. | Unlike in England, there was often a lack of direct contact between ministers in Scotland and Wales on the one hand and Public Health Scotland and Public Health Wales on the other. As Professor Nick Phin (Director of Public Health Science at Public Health Scotland from January 2021) said, in Scotland this created at least a risk that advice being provided to the Chief Medical Officer for Scotland at the National Incident Management Team meetings was subject to a filter, with:

“people … interpreting what they heard and … trying to then re-interpret that in the context of what they were being asked”.122 |

| 9.67. | Public Health Scotland was a key component in implementing policy, but had limited involvement during the policy formulation stage. This gave rise to a risk that Scottish Government policy could not be properly implemented. There were also delays built into the system, which led to inefficiency. Once a policy had been devised, it fell to Public Health Scotland to provide the relevant guidance, but that guidance then had to be approved by ministers. In some instances, this might have led to the guidance being out of date even before it had commenced.123 |

Wales

| 9.68. | Public Health Wales is an NHS trust dedicated to improving health, reducing health inequalities and protecting public wellbeing in Wales. It provided a wide range of advice to the Welsh Government. As Dr Tracey Cooper (Chief Executive of Public Health Wales from June 2014) put it: “[T]he advice was about everything.”124 This included lockdowns and other interventions. Public Health Wales also played a key role in developing several Welsh Government plans and strategies.125 Dr Cooper noted that its role was initially unclear and often extended beyond its mandate.126 |

| 9.69. | Public Health Wales eventually played a crucial advisory role during the pandemic, but it was not adequately consulted by the Welsh Government in January and February 2020. Mr Drakeford told the Inquiry:

“I cannot rule out the possibility that, had the Public Health Wales view been more directly communicated to ministers, that that would have made a difference to the actions that we took, but the system that we had … is that the Public Health Wales does not speak directly to ministers by routine, they speak to Welsh ministers via the Chief Medical Officer.”127 |

| 9.70. | Requests for advice to Public Health Wales from the Welsh Government began to increase significantly from mid-February 2020 and surged from early March 2020. Clarity about its role improved only after the Public Health Protection Response Plan was produced on 4 May 2020.128 The role of Public Health Wales in the pandemic should have been more clearly defined from the outset, rather than months after the pandemic started. |

| 9.71. | Public Health Wales does not hold a comprehensive record of all of the advice provided during this crucial time. From 12 October 2020, the Welsh Government adopted a more systematic approach to requesting advice from Public Health Wales and formal advice notes were produced.129 This underscores the importance of adopting formal commissioning processes that ensure all advice is recorded. |

Northern Ireland

| 9.72. | The Public Health Agency was established under the Health and Social Care (Reform) Act (Northern Ireland) 2009.130 Its functions can be summarised under three broad headings: improving health and social wellbeing and reducing health inequalities; health protection; and service development in Northern Ireland. |

| 9.73. | At the time of the pandemic, Professor McBride – on behalf of the Department of Health (Northern Ireland) – was the senior departmental sponsor for the Public Health Agency.131 Dr Joanne McClean (Director of Public Health at the Public Health Agency from September 2022) explained that sponsorship entailed the provision of direction and ensuring that the Public Health Agency performed in accordance with its statutory duties and the wishes of the Minister of Health.132 |

| 9.74. | The Public Health Agency did not have the same sort of advisory function as its counterparts in Wales and Scotland. It provided information – for example, relating to contact tracing, testing capacity, surveillance and care homes – to the Department of Health (Northern Ireland), which then determined what ought to be communicated to the Northern Ireland Executive Committee through the Minister of Health.133 The Public Health Agency did not produce its own guidance, as it did not have the capacity or expertise to do so, nor did it have access to sufficiently up-to-date information. It relied upon advice and guidance produced by Public Health England and, where necessary, adapted it for use in Northern Ireland.134 |

| 9.75. | Prior to the pandemic, questions had been raised as to whether the Public Health Agency could discharge its statutory functions. In 2017, the Department of Health (Northern Ireland) aired concerns about the depletion of the Public Health Agency’s staffing and experience. In 2018, this concern was raised again. At a mid-year accountability meeting on 12 December 2018, Professor McBride noted that it was vital to ensure that resources were in place to effectively deal with any potential threat or event.135 After 2018, the situation deteriorated still further as a result of the Public Health Agency losing critical staff and experience.136 |

| 9.76. | The Public Health Agency is an example of an important public body in Northern Ireland whose capacity had been steadily eroded in the years leading up to the pandemic. Professor McBride’s concern that it had insufficient resources available to meet a significant event was well founded. At the outset of the pandemic, it had a number of staff vacancies and had made interim appointments in key roles.137 In an email to Professor McBride on 3 February 2020, a senior medical officer within the Department of Health (Northern Ireland) noted that the Health and Social Care Board (which at that point commissioned health services in Northern Ireland) and the Public Health Agency had less capacity and less resilience than in 2009 (during the swine flu pandemic).138 |

| 9.77. | It is also clear that, in the early stages of the pandemic, the Department of Health (Northern Ireland) changed its working relationship with the Public Health Agency.139 Amid concerns about the ability of the Public Health Agency to provide reliable information about the numbers of daily deaths, the Department of Health (Northern Ireland) transferred a number of functions of the Public Health Agency to itself in April 2020.140 Richard Pengelly, Permanent Secretary to the Department of Health (Northern Ireland) from July 2014 to April 2022, described this as the department stepping into a:

“much more command and control-type approach as opposed to the normal relationship between sponsor department and arm’s length body where there’s quite a remove between the two organisations”.141 |

| 9.78. | A rapid review of the Public Health Agency’s functions in relation to the pandemic was commissioned by it in June 2020 and reported in July 2020.142 The main finding was that there was not “a sufficient resource in the agency to do all of the things which need to be done at this time”.143 The review noted that this had negatively impacted upon the general ability of the Chief Executive and Director of Public Health to keep both the Public Health Agency’s board and the Department of Health (Northern Ireland) informed about the Public Health Agency’s work. It suggested that this might offer a partial explanation for the “tension” that at times existed between the Public Health Agency and the Department of Health (Northern Ireland).144 |

| 9.79. | It is concerning that, at the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Public Health Agency had less capacity and resilience than it had had a decade previously. It is regrettable that this, in turn, directly impacted upon its ability to perform its functions and on its relationship with the Department of Health (Northern Ireland). |

| 9.80. | The scientific resource provided by the public health bodies in all four nations is an essential element of the response to a pandemic. Accordingly, the capacity of each of these bodies should be strengthened so that they are able properly to fulfil their role in the event of a future emergency. |

Recruitment and selection of participants

| 9.81. | All members of and participants in the UK’s scientific advisory groups are to be highly commended for their exemplary service in the course of the pandemic. The Inquiry nevertheless identified two areas in which the recruitment of participants for scientific advisory groups could be improved for the future: open and transparent recruitment processes and also greater diversity of participants. |

| 9.82. | SAGE is not a permanent body and has no standing participants.145 The participants of SAGE and its sub-groups are recruited on an ad hoc basis according to the requirements of the specific emergency. Each meeting brings together “scientists relevant to the questions that are thought most important at that point in time“.146 The flexibility afforded by this approach is an advantage of the SAGE system. During the Covid-19 pandemic, it meant that the composition of SAGE could be adapted when necessary and tailored to evolving policy needs. As Dr Stuart Wainwright, Director of the Government Office for Science from December 2019 to June 2023, suggested: “You need the expertise in the room for the situation at hand.”147 |

| 9.83. | The rapid identification of scientific experts is crucial during a public health emergency. It is equally important that those experts are drawn from a diverse range of disciplines, backgrounds and experience. The incorporation of multiple voices, including those with dissenting views, helps to build sufficient challenge into the advisory process and to guard against ‘groupthink’.148 |

| 9.84. | However, when SAGE was activated in January 2020, there was no “systematic process” in place to ensure that the participant experts were adequately diverse. Professor Vallance told the Inquiry:

“The first three SAGE meetings were attended by a number of experts chosen because of their expertise in the fields most directly relevant to the questions SAGE had to address, as well as some officials from DHSC [the Department of Health and Social Care], PHE and some CSAs [Chief Scientific Advisers].”149 In a medical crisis, the Chief Medical Officer will also usually “suggest medical and public health experts”.150 The initial list of invitees was determined by Professors Vallance and Whitty, in consultation with the SAGE Secretariat, and included: “people who had experience of epidemic modelling and other sciences in the context of previous emergencies such as Ebola”.151 |

| 9.85. | Professor Vallance acknowledged that there was a tendency to appoint scientific experts who were “known” and that this posed a “risk to diversity“.152 A number of witnesses expressed concerns about this issue.153 For example, Dr Leon Danon (Associate Professor in Infectious Disease Modelling and Data Analytics at the University of Bristol and participant in SPI-M-O from February 2020) noted that SPI-M-O was dominated by a group of epidemiological modellers from Imperial College London and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. He considered that this:

“led to advice being less robust than it could have been if a broader group of experts was empowered to provide analysis and advice from the outset”.154 |

| 9.86. | Professor Lucy Yardley, Professor of Health Psychology at the University of Bristol and the University of Southampton and Co-Chair of SPI-B from April 2020, noted that the lack of diversity was exacerbated by a shortage of resources. She told the Inquiry:

“There was no time or resource available in the early stages of the pandemic to undertake a systematic search for a wide, representative group or to engage in formal processes for selecting and inviting members … only people with the capacity to free up substantial time for SPI-B from their day jobs and home commitments could make a significant input.”155 |

| 9.87. | Similarly, membership of the Scottish Government Covid-19 Advisory Group was drawn via existing networks and relationships. The group included epidemiologists, behavioural scientists, virologists and public health experts. However, there was no direct representation of at-risk or vulnerable groups or any direct expertise in respect of health economics or ethics.156 Experts in these areas would likely have added extra evidence and context to the matters under discussion. |

| 9.88. | Some members of the Technical Advisory Group in Wales felt that it also lacked diversity.157 Dr Orford agreed that improving group composition was crucial and should be addressed before a future pandemic.158 Some sub-group members also commented that a lack of diverse representation contributed to insufficient challenge in discussions at times.159 |

| 9.89. | Members of the Strategic Intelligence Group in Northern Ireland were selected and approached by Professor Young after discussion with Professor McBride.160 Professor Young explained that the membership was selected to provide a range of scientific expertise and representation from key sectors in Northern Ireland.161 Members were also invited to suggest additional members, but, beyond this, there was no selection process to consider wider participation. |

| 9.90. | Professor Whitty cautioned against the inclusion of “every possible representative group”, on the basis that this would have “inevitably led to less opportunity for those present to challenge and debate the science”. The Inquiry recognises the danger. The importance of access to a range of perspectives must be weighed against the need to provide advice within a short timeframe and to avoid the membership of advisory groups becoming, as Professor Whitty put it, “impossibly large”.162 However, this does not negate the need for a balance to be struck among those present in terms of their scientific disciplines, backgrounds and experiences. The inclusion of experts from a more diverse range of backgrounds might have helped to challenge orthodox scientific thinking and brought wider experience of public health conditions on the ground. The Inquiry notes the positive steps being taken to improve diversity and in response to the Module 1 Report in this respect.163 |

| 9.91. | To prepare for a future crisis, a process of open and transparent recruitment should take place to identify a list of experts willing to participate in advisory groups when their expertise is required and to act as chairs of potential sub-groups. This would help to break down barriers and improve diversity in terms of the range of participants’ disciplines and the institutions from which they are drawn. It would also help to build a broader pool of expertise that can be used to regularly refresh or rotate participation during a prolonged emergency. Mechanisms – for example, annual meetings – could also be put in place to build professional networks in order to enable efficient collaboration and understanding of disciplines in future crises. |

Recommendation 3: Register of experts

The Government Office for Science (GO-Science) should develop and maintain a register of experts across the four nations of the UK who would be willing to participate in scientific advisory groups, covering a broad range of potential civil emergencies. The register should be regularly refreshed through open calls for applications.

Attendance of officials

| 9.92. | As the response to the pandemic escalated, officials from across the UK government (including the Cabinet Office, Department of Health and Social Care, the Treasury and 10 Downing Street) began to attend SAGE meetings as observers.164 This enabled them to listen to the discussions, feed in required policy perspectives, ask questions and report the information gathered to their home organisation.165 |

| 9.93. | Likewise, Welsh Government policy leads joined the sub-groups of the Technical Advisory Group aligned with their areas.166 Dr Orford and Robin Howe, Chair of the Testing sub-group, noted the value of officials attending to hear debates and grasp the strength of the evidence.167 |

| 9.94. | The Scottish Government had representatives from within its health and social care directorates in attendance at Scottish Government Covid-19 Advisory Group meetings. Representatives included the co-directors and Deputy Director of Covid Health Response, the Chief Statistician and the Deputy Director of the Testing and Contact Tracing Policy Division. Some of its standing members also held advisory positions within the Scottish Government, including the Chief Social Policy Adviser.168 |

| 9.95. | In Northern Ireland, some officials from within the Department of Health (Northern Ireland) attended meetings of the Strategic Intelligence Group. These included the Chair of the Contact Tracing Service Steering Group and the Senior Statistician in the Department of Health (Northern Ireland).169 |

| 9.96. | The attendance, as observers, of relevant officials at meetings of scientific advisory groups enables the salient features of the debate to be relayed to absent decision-makers. However, this should not be used as a substitute for the formal output contained in the official minutes, papers and briefings. Decision-makers should always refer to such formal output documents for an authoritative statement of scientific advice. |

Commissioning process

| 9.97. | The processes of commissioning advice from the scientific advisory groups across the UK differed by nation and evolved as the pandemic progressed. In the initial months of the pandemic, SAGE and its sub-groups received commissions for advice primarily from the Civil Contingencies Secretariat (which provided the secretariat for COBR). From May 2020 onwards, the responsibility for commissioning advice moved to the Covid-19 Taskforce in the Cabinet Office.170 |

| 9.98. | Sub-groups could also self-generate their work.171 For instance, much of the research undertaken by SPI-M-O was not commissioned. Its participants often conducted their own analyses, which they brought to the committee for discussion.172 |

| 9.99. | The commissioning of scientific advice during the Covid-19 response was not always focused and achievable. Some commissions were too narrow, while others were too broad. For example, Professor Vallance said that the UK government often asked questions that were “too granular for the evidence that was available”. SPI-M-O therefore became “overwhelmed by requests to model different and very specific scenarios and policy options“.173 Professor Horby said that direct commissions for NERVTAG from Public Health England were, at times, “too broadly specified”.174 Professor James Rubin (Professor of Psychology and Emerging Health Risks at King’s College London and Chair of SPI-B from February 2020 to June 2021) told the Inquiry that early commissions to SPI-B were occasionally “unclear or vague“.175 Professor Yardley noted that some questions from decision-makers were poorly formulated.176 It was often necessary to clarify or modify those questions, which meant that the provision of advice was delayed. |

| 9.100. | This confusion was compounded by the tendency of government departments to directly approach SAGE sub-groups for advice rather than routing their requests in the appropriate manner.177 The use of direct commissions subjected participants to intense and unmanageable workloads. Professor Catherine Noakes, Professor of Environmental Engineering at the University of Leeds and Chair of the Environmental Modelling Group, a sub-group of SAGE, recalled that these commissions often came from the Cabinet Office with “almost impossible timescales”.178 The Inquiry agrees with Professor Whitty’s reflection:

“[A]n early central clearinghouse for policy requests to SAGE and its subgroups with senior scientists and policymakers triaging the requests would have improved prioritisation.”179 |

| 9.101. | The Scottish Government typically requested the Scottish Government Covid-19 Advisory Group to provide scientific advice through a commission process that was developed over time.180 Professor Morris estimated that around 80% of the group’s advice was commissioned by the Scottish Government.181 However, the group could also provide advice to the Scottish Government on its own initiative:

“where a particular topic was seen as a priority at that stage in the pandemic and the [Scottish Government Covid-19 Advisory Group] judged it important to provide further information on this”.182 The Scottish Government Covid-19 Advisory Group provided advice without commission on eight occasions, on topics ranging from testing to risk communication.183 Professor Morris noted: “This was a strength of an independent group as it had the flexibility to do more than just answer the questions that were posed.”184 |

| 9.102. | In Wales, advice was initially provided by the Technical Advisory Group as needed on an ad hoc basis, without a formal commissioning structure.185 Members of its sub-groups found the initial lack of a formal process for commissions challenging due to the pressures of demand and the very short deadlines set.186 |

| 9.103. | In Northern Ireland, there was no cross-government chief scientific adviser or cross-government advisory body. Scientific advice was provided to the Northern Ireland Executive Committee exclusively by the Department of Health (Northern Ireland) through the Minister of Health or by the attendance of the Chief Medical Officer for Northern Ireland and the Chief Scientific Adviser to the Department of Health (Northern Ireland) at Executive Committee meetings. Accordingly, the Executive Committee could not – and did not seek to – directly commission scientific advice from the Strategic Intelligence Group. The recently established post of Chief Scientific and Technology Adviser will provide a vehicle for delivering collective advice to the Northern Ireland Executive in future. |

| 9.104. | The commissioning of scientific advice improved, however, as the pandemic progressed and governance structures evolved. In the summer of 2020, the Government Office for Science and the Covid-19 Taskforce worked together to establish a revised commissioning process. This aimed to ensure that requests for scientific advice were “triaged and tracked properly”.187 From December 2020 onwards, SAGE and SPI-M-O meetings were attended by the leader of the Covid-19 Taskforce, which facilitated a “better understanding of what could be conceivable policy”.188 |

| 9.105. | In Wales, as a result of continuing pressure on the limited resources of the Technical Advisory Group, a formal process for commissioning advice was introduced in March 2021 and, from April 2021, a steering group provided senior oversight.189 Each sub-group of the Technical Advisory Group continued to proactively review new evidence relevant to its area of focus.190 |

| 9.106. | Scientific advisory groups are likely to work most effectively where the context of the tasks set for them is understood and the advice that is sought forms part of a clearly defined, strategic plan. However, the Inquiry heard that participants in UK advisory groups did not always understand the UK government’s aims.191 There was a lack of clearly stated policy objectives and ‘red lines’. This hampered the groups’ ability to provide useful and targeted advice and led to conservatism with regard to the interventions that were modelled. For example, Professor John Edmunds, Professor of Infectious Disease Modelling at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and a participant in SPI-M, stated that SPI-M-O was:

“slow to model the implication of lockdown policies in detail … It was not clear to me that such radical measures were politically acceptable and so we did not spend as much time on them in early March as we should have.”192 |

| 9.107. | A similar issue arose in Wales in respect of the Welsh Government’s aims. Dr Robert Hoyle, Head of Science at the Welsh Government Office for Science from May 2019 and a member of the Technical Advisory Cell and Technical Advisory Group, told the Inquiry:

“[I] asked the question on my first meeting about what the strategy was, and essentially it was to reduce harm or harms, and I was never convinced that it was any clearer than that.”193 |

| 9.108. | The work of the advisory groups will be considerably assisted if, from the outset of any future pandemic:

|

Consensus approach

| 9.109. | The emergency nature of a SAGE activation means that its advice must be produced and communicated to decision-makers at speed. The official written output of SAGE during the Covid-19 response was its minutes. These were prepared by the SAGE Secretariat in the Government Office for Science, signed off by the co-chairs and disseminated across government after each meeting. The minutes took the form of a consensus statement reflecting the discussion in SAGE meetings.194 The consensus approach was devised in response to a recommendation made by Dame Deirdre Hine in July 2010 that the UK government and devolved administrations should be “presented with a unified, rounded statement of scientific advice”.195 |

| 9.110. | Professor Dame Angela McLean, Chief Scientific Adviser to the Ministry of Defence from 2019 to 2023 and Government Chief Scientific Adviser from April 2023, explained that a consensus position is “not the same as reaching a compromise view“.196 As Professor Whitty put it, SAGE provides a “single integrated view of the science provided by multiple disciplines”. This does not mean “it can or should provide a consensus, except when consensus reflects the reality of scientific opinion”. It attempts to provide:

“a central view of scientific understanding at that point in time, and where necessary indicates the spread of opinion or uncertainty around that central view”.197 |

| 9.111. | A consensus view inevitably carries more weight than an individual opinion, but it also takes more time to generate, which necessarily delays the provision of advice to decision-makers. In an emergency situation, a balance must be struck between the robustness of advice and the need to produce it rapidly. Professor Medley estimated that the delay created by the consensus process was “at most two calendar days”.198 This delay was not excessive and was worthwhile because it led to a unified view formulated by multiple specialist disciplines. |

| 9.112. | Some SAGE minutes recorded uncertainty by setting out a “level of certainty rating” using grading expressed in terms of confidence.199 This provided decision-makers with clarity as to the level of certainty expressed in the scientific advice. However, this approach was adopted only occasionally rather than routinely. Professor Whitty reflected:

“We should have from the beginning had the discipline more thoroughly of saying high confidence and low confidence. I think that was a sensible way to do it.”200 |

| 9.113. | The consensus approach, while providing decision-makers with a concise synopsis of the evidence on which SAGE’s advice was based, meant that the minutes failed to capture the full extent of the discussion that had taken place. Minority or dissenting opinions, which could have been significant, were excluded from the minutes. Professor Mark Woolhouse, Professor of Infectious Disease Epidemiology at the University of Edinburgh and a participant in SPI-M-O, expressed the following concern:

“SAGE and its subgroups put too much emphasis on consensus and too little on minority views. The most likely outcome – intended or otherwise – of only expressing a single view is that it presents policy makers with an overly limited set of options and so will channel policy decisions along a particular route.”201 |

| 9.114. | Those who relied on the written minutes could be led to believe that the advice represented the common view of all expert participants. Indeed, in Professor Woolhouse’s experience:

“[R]eporting what was effectively the majority view might have given an impression of groupthink … minority views were not always communicated to officials and ministers.”202 |

| 9.115. | While Professor Whitty acknowledged that this was a “potential weakness” of the consensus process, he noted that the minutes were not the sole medium by which SAGE’s advice was communicated. There were two additional mechanisms by which decision-makers “could get the spread of opinion”.203 Firstly, Professors Whitty and Vallance regularly delivered verbal briefings to the Prime Minister and others, during which they “tried to communicate the range of opinion around the central SAGE conclusion”.204 However, this assisted only those who were present at such briefings or who had access to any read-out (to the extent that they had an understanding of what was being summarised). Secondly, officials from government departments were routinely invited to attend SAGE meetings as observers, and they did attend. They were therefore privy to the full debate that took place and in a position to challenge the accuracy of the consensus statement set out in the minutes if they wished to do so.205 It is not clear, however, whether such officials generally felt able to do so. |

| 9.116. | The Chief Medical Officer for Scotland also formulated advice on the “centre ground” where there was most confidence and agreement. It was considered unhelpful to present a wide range of different – often conflicting – medical or scientific views to ministers.206 The advice of the Scottish Government Covid-19 Advisory Group was provided in writing to the Scottish Government, along with a number of ‘deep dives’. Written advice was ordinarily provided on a consensus basis. Where there was no consensus, this was stated.207 In Wales, the Technical Advisory Cell and the Technical Advisory Group sought to create an environment where different opinions could be voiced, but they also sought to provide consensus of opinion to “ensure there was an agreed position on papers”.208 If consensus could not be reached, this would be included in their advice. Similarly, when briefing ministers in Northern Ireland, Professor McBride sought to include a range of consensus estimates for the potential course of the pandemic, including potential case numbers and the range of potential impact on hospital admissions.209 Although, according to Professor Young, “core decision makers (including Ministers, at times) looked for certainty in terms of scientific advice”, the limitations of knowledge and evidence were also made clear.210 |

| 9.117. | On balance, the consensus mechanism was effective during the Covid-19 response. It considerably strengthened and broadened the scientific advice that was produced, while avoiding a situation in which ministers were faced with the competing and complex opinions of various experts. As Professor Sir Jonathan Van-Tam, Deputy Chief Medical Officer for England from October 2017 to March 2022, pointed out:

“If the CMO and the GCSA [Government Chief Scientific Adviser] were to give non-scientists (such as the Prime Minister) a range of different opinions, I think it is inevitable that they would simply ask them which one they ought to listen to; the result being that the Prime Minister would be making decisions on the basis of one person’s view rather than a broad range that have been discussed and tested before being assimilated into an agreed central opinion.”211 |

| 9.118. | The delays caused by the consensus process would have been significantly longer if every variant of opinion had been recorded. This would not have been realistic in a fast-moving crisis. However, in future emergencies, minutes setting out consensus views should indicate the level of confidence within the group. They should also highlight more clearly any uncertainties and explain the drivers of those uncertainties. In addition, it would be useful for the advisory body to provide a menu of options available for use by decision-makers in any response. The provision of these potential options and advice on the options should not be confused with policy-making, which remains a matter for decision-makers. |

Other sources of challenge

| 9.119. | Decision-makers were not solely reliant on the scientific advisory bodies or individual advisers. They were also able to access and call upon other sources of external expertise to help challenge advice received or to ensure a greater diversity of opinion. Much comment and expertise existed in the public domain, with Independent SAGE (see below) being one of the most visible commentators. |