A report by The Rt Hon the Baroness Hallett DBE

Chair of the UK Covid-19 Inquiry

Volume I: Introduction and key events from January 2020 to May 2022

Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 26 of the Inquiries Act 2005

Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 20 November 2025

HC 1436-I

CORRECTION SLIP

Title:

UK Covid-19 Inquiry

Modules 2, 2A, 2B, 2C: Core decision-making and political governance

Volume I: Introduction and key events from January 2020 to May 2022

A report by The Rt Hon the Baroness Hallett DBE

Chair of the UK Covid-19 Inquiry

Session: 2025

HC 1436-I

ISBN: 978-1-5286-5449-4

Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 20 November 2025

Corrections:

Text currently reads (Chapter 2, para 41):

In Scotland, on 24 January 2020, Ms Sturgeon received a briefing from Health Protection Scotland incorrectly stating: “We now know that people carrying the virus are only infectious to other people when experiencing symptoms.”104 Ms Sturgeon challenged the view that asymptomatic transmission was not possible.105 The following day she received further advice from Health Protection Scotland, which explained that “it is likely that person to person transmission, when it does occur, mostly involves transmission of virus from people with symptoms” and that:

Text should read:

In Scotland, on 24 January 2020, Ms Sturgeon received a briefing from the Scottish Government’s Health Protection Policy Team incorrectly stating: “We now know that people carrying the virus are only infectious to other people when experiencing symptoms.”104 Ms Sturgeon challenged the view that asymptomatic transmission was not possible.105 The following day she received advice from Health Protection Scotland, which explained that “it is likely that person to person transmission, when it does occur, mostly involves transmission of virus from people with symptoms” and that:

Date of correction: 16 January 2026

Text currently reads (Chapter 3, para 16):

Richard Pengelly, Permanent Secretary to the Department of Health (Northern Ireland) from July 2014 to April 2022, had written to the Chief Executives of health and social care trusts on 1 March 2020, warning them that:

Text should read:

Richard Pengelly, Permanent Secretary to the Department of Health (Northern Ireland) from July 2014 to April 2022, had written to the Chief Executives of health and social care trusts on 26 March 2020, warning them that:

Date of correction: 16 January 2026

| Figure | Description |

|---|---|

| Figure 1 | Message from Mr Hancock to Mr Cummings, 25 January 2020 |

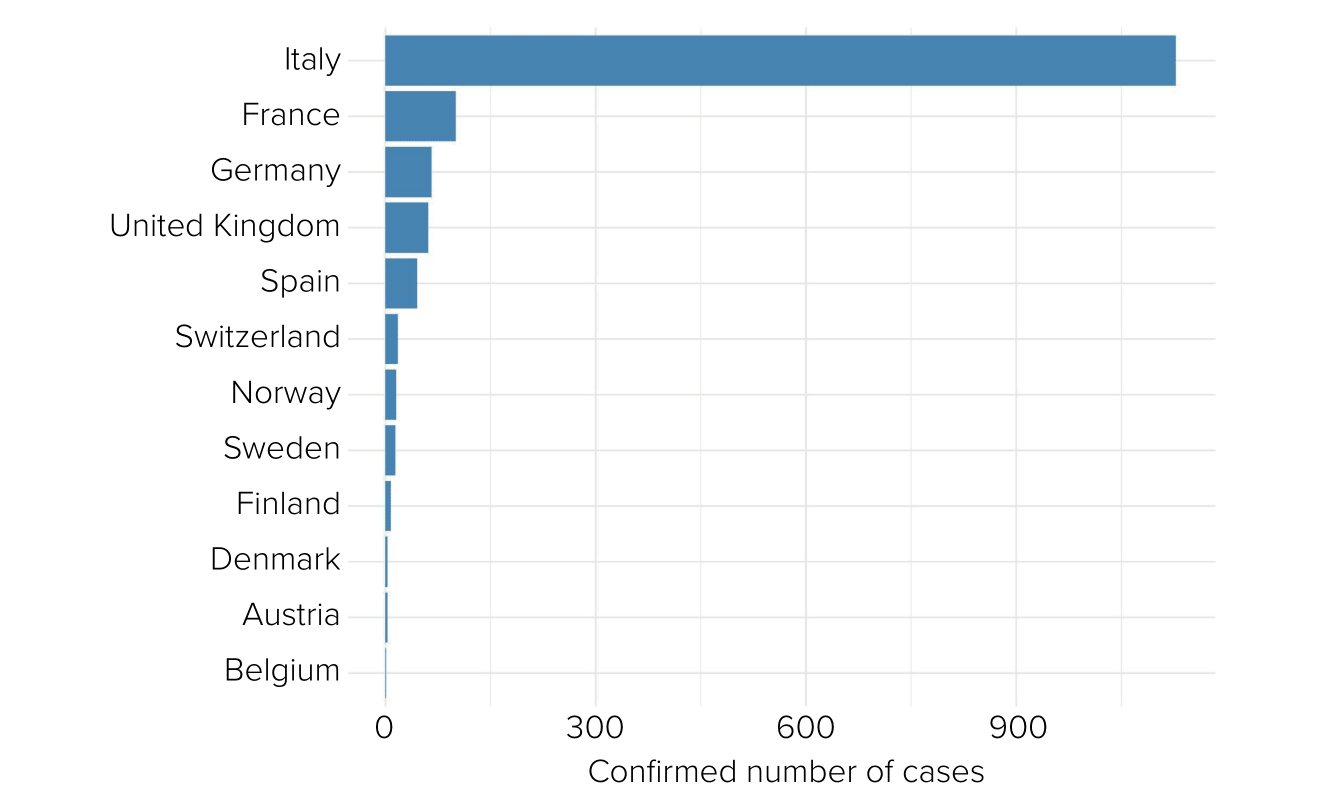

| Figure 2 | Reported cases in selected European countries in February 2020 |

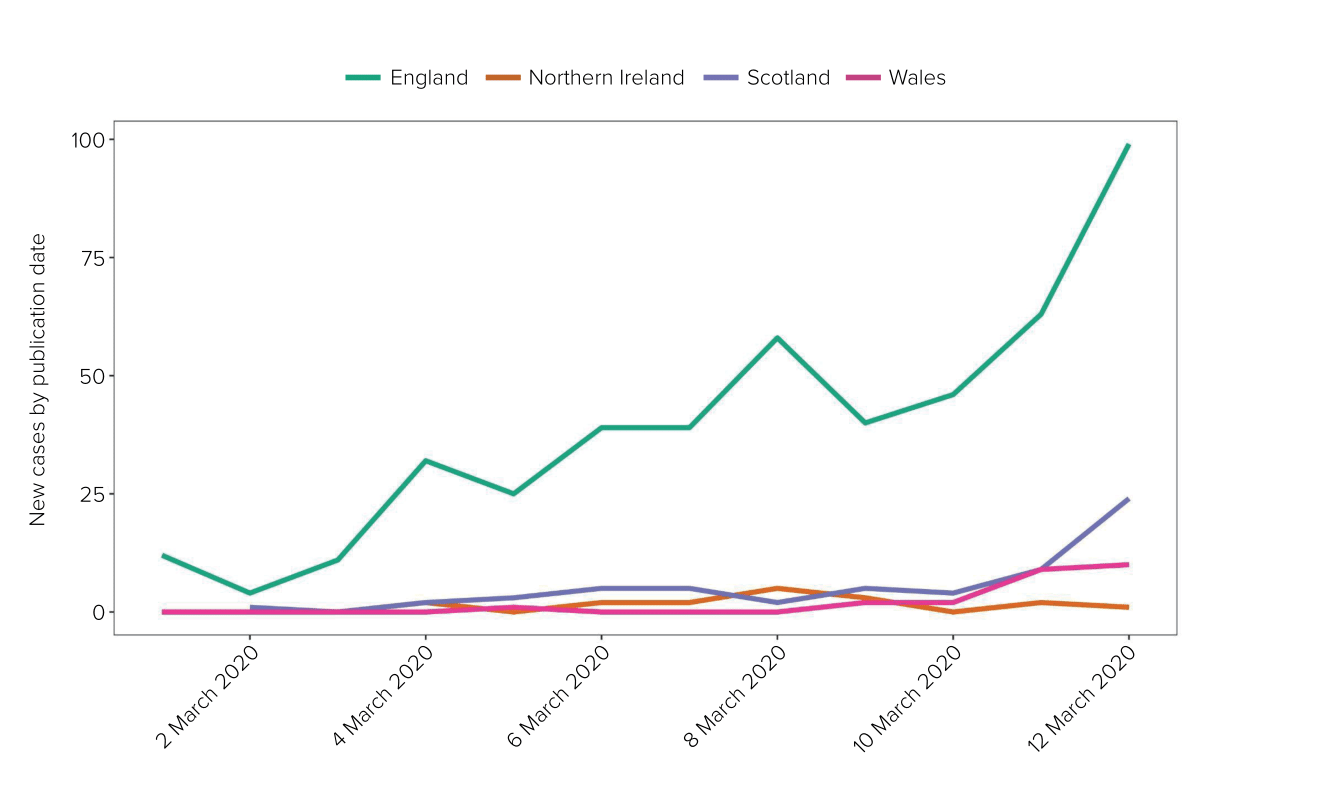

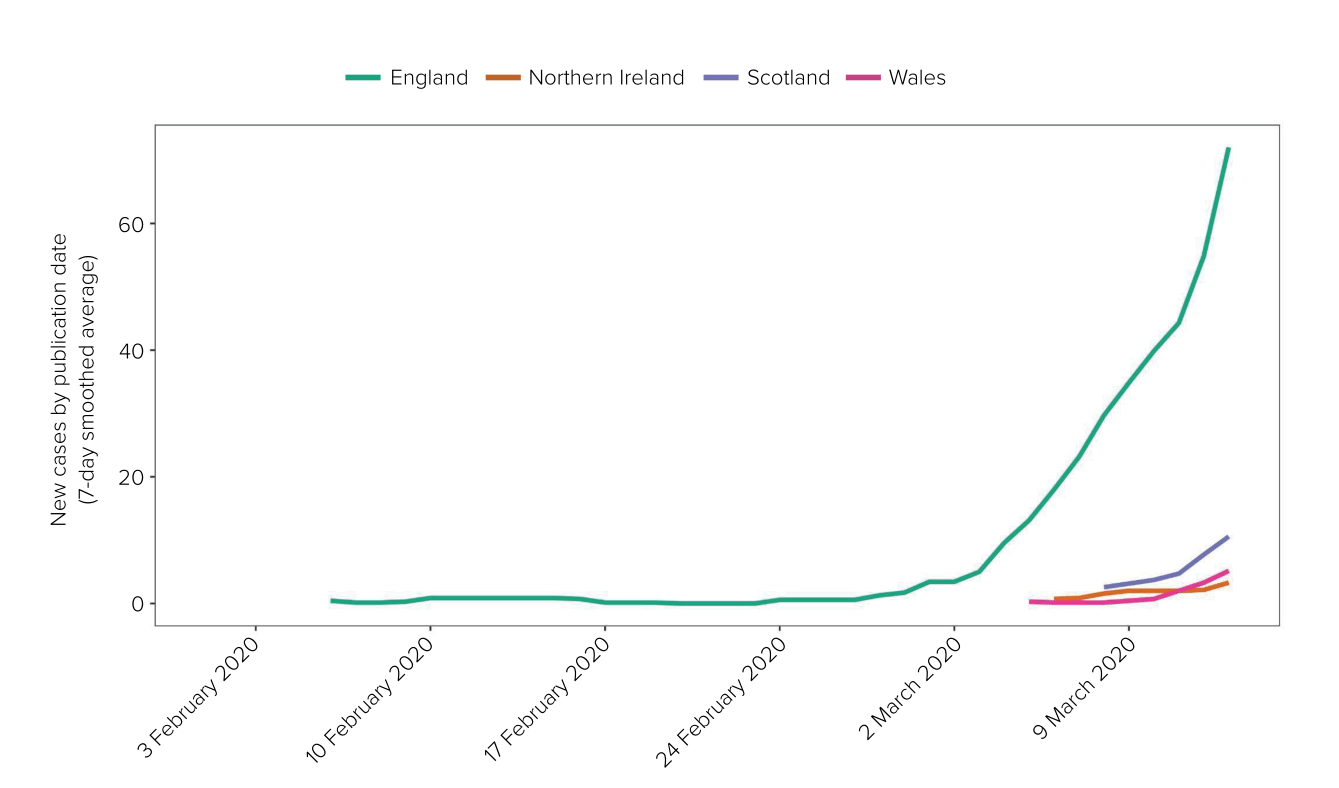

| Figure 3 | Daily confirmed cases from 1 to 12 March 2020 across the UK |

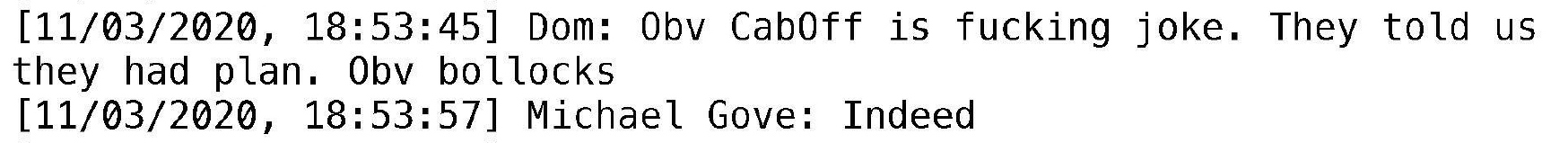

| Figure 4 | Exchange of messages between Mr Cummings and Mr Gove on 4 March 2020 |

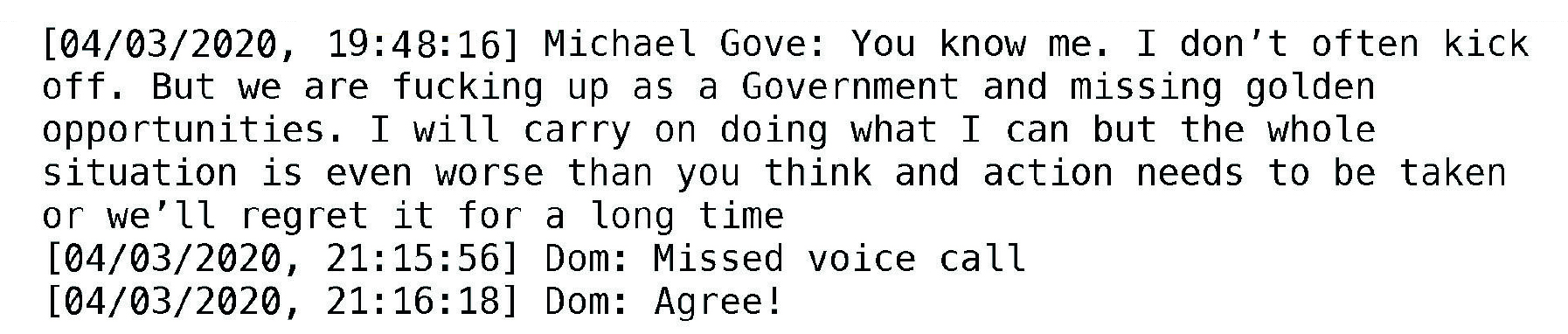

| Figure 5 | Exchange of messages between Mr Cummings and Mr Gove on 11 March 2020 |

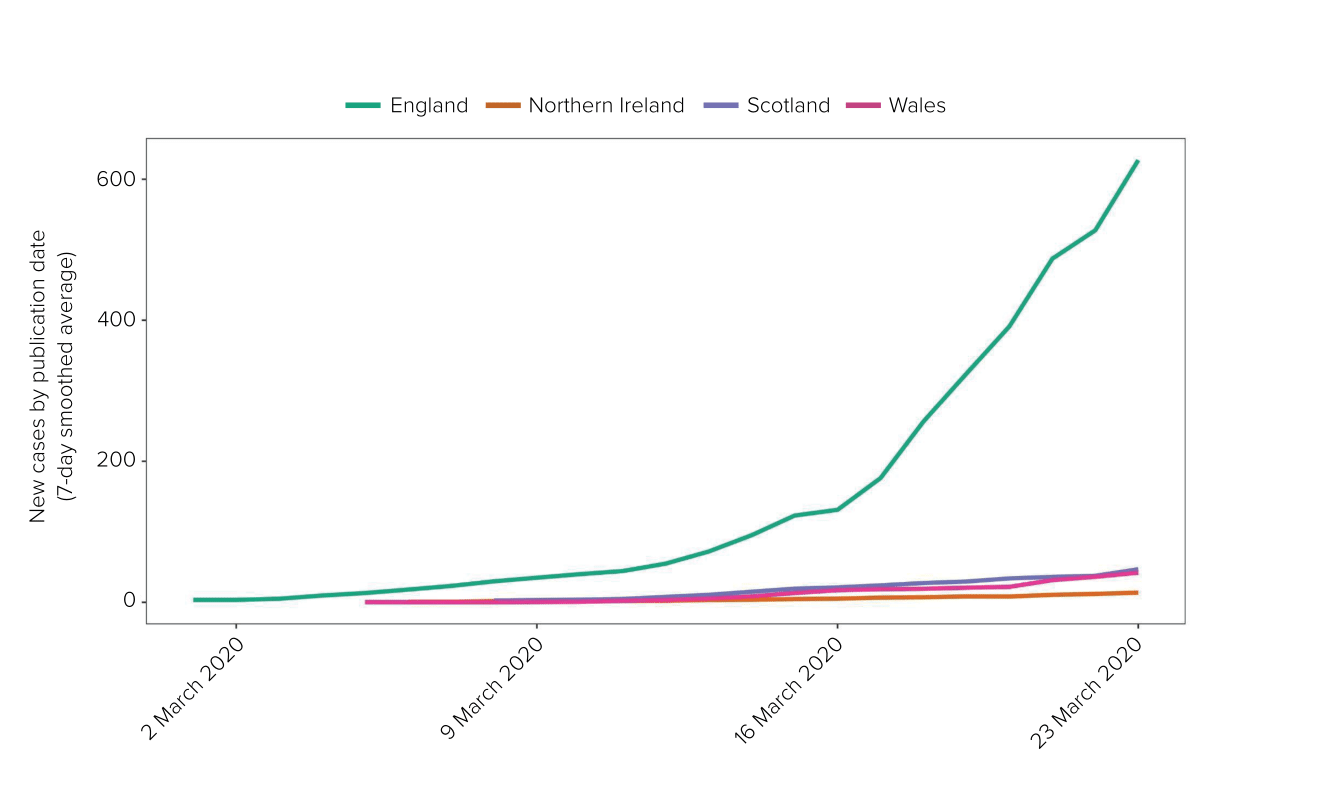

| Figure 6 | Daily confirmed cases from 2 March to 23 March 2020 across the UK |

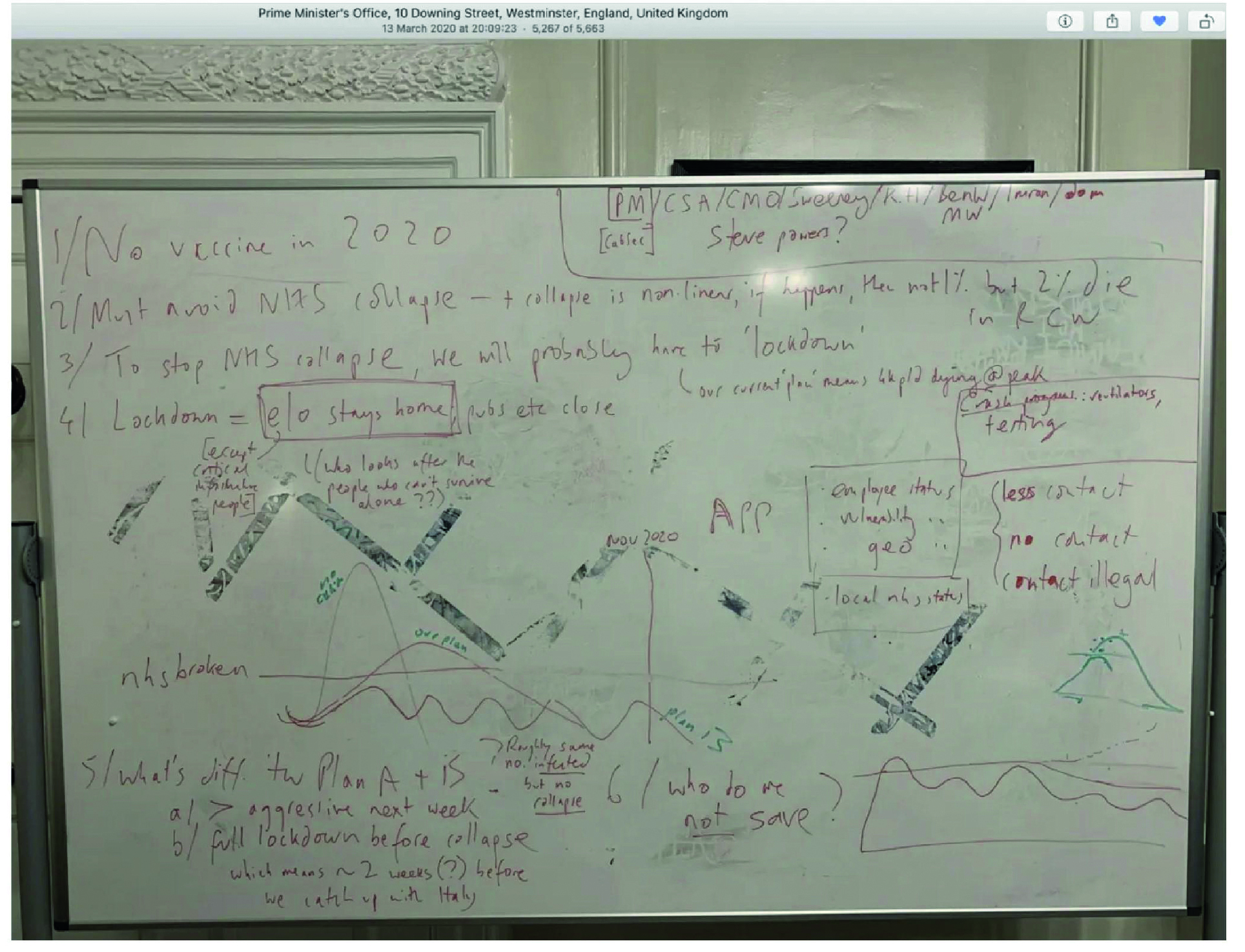

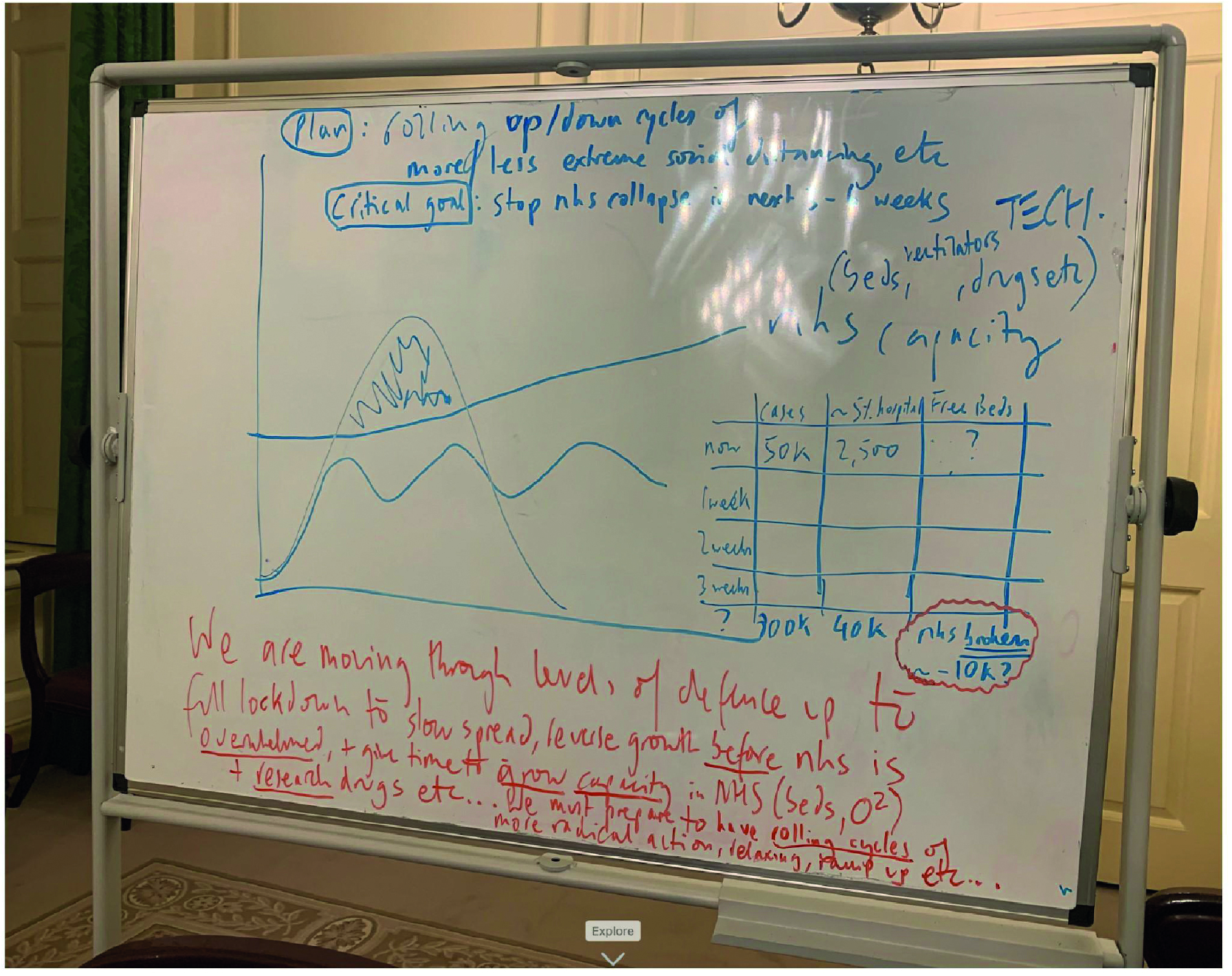

| Figure 7 | Notes on a whiteboard during the meeting at 10 Downing Street on 13 March 2020 |

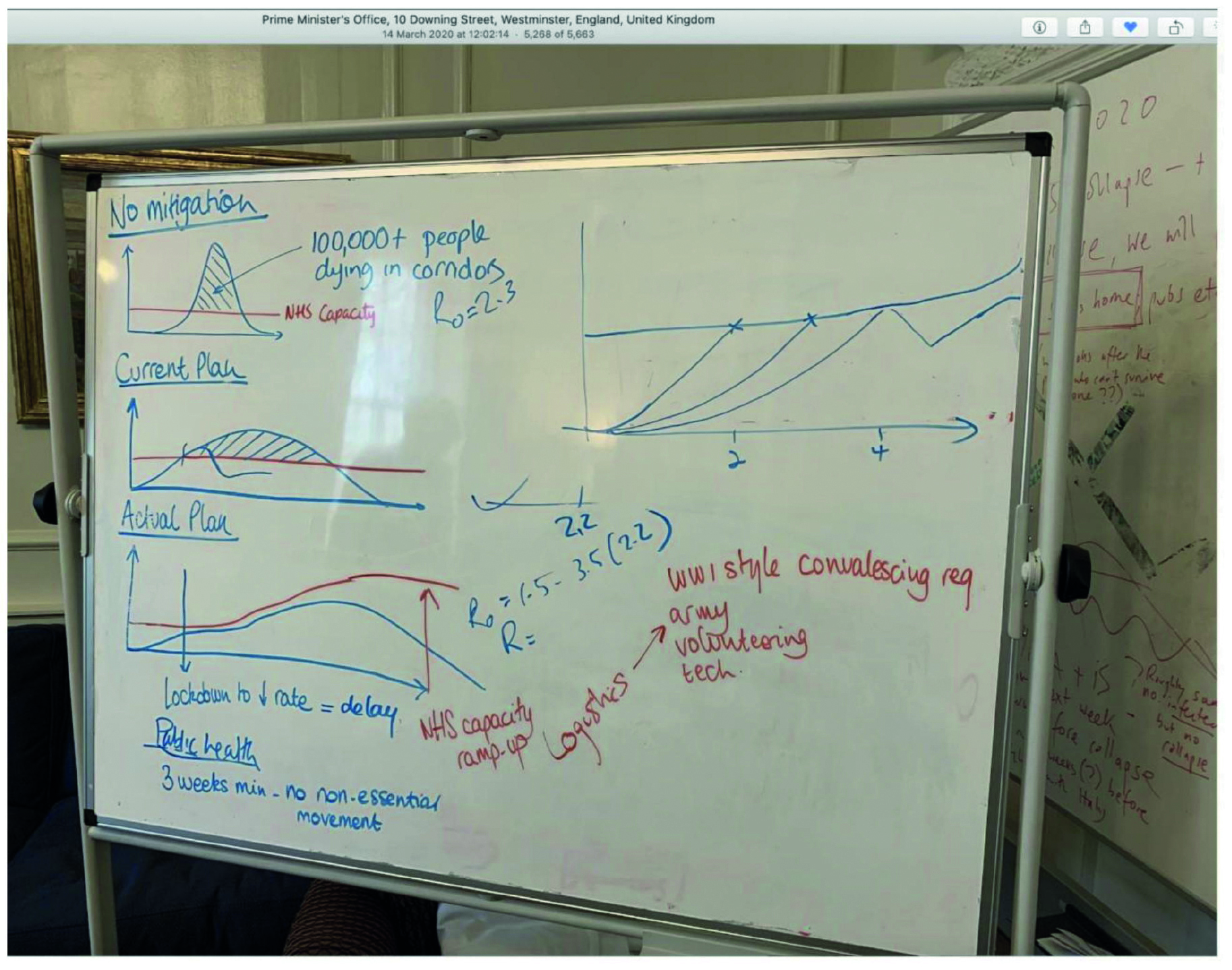

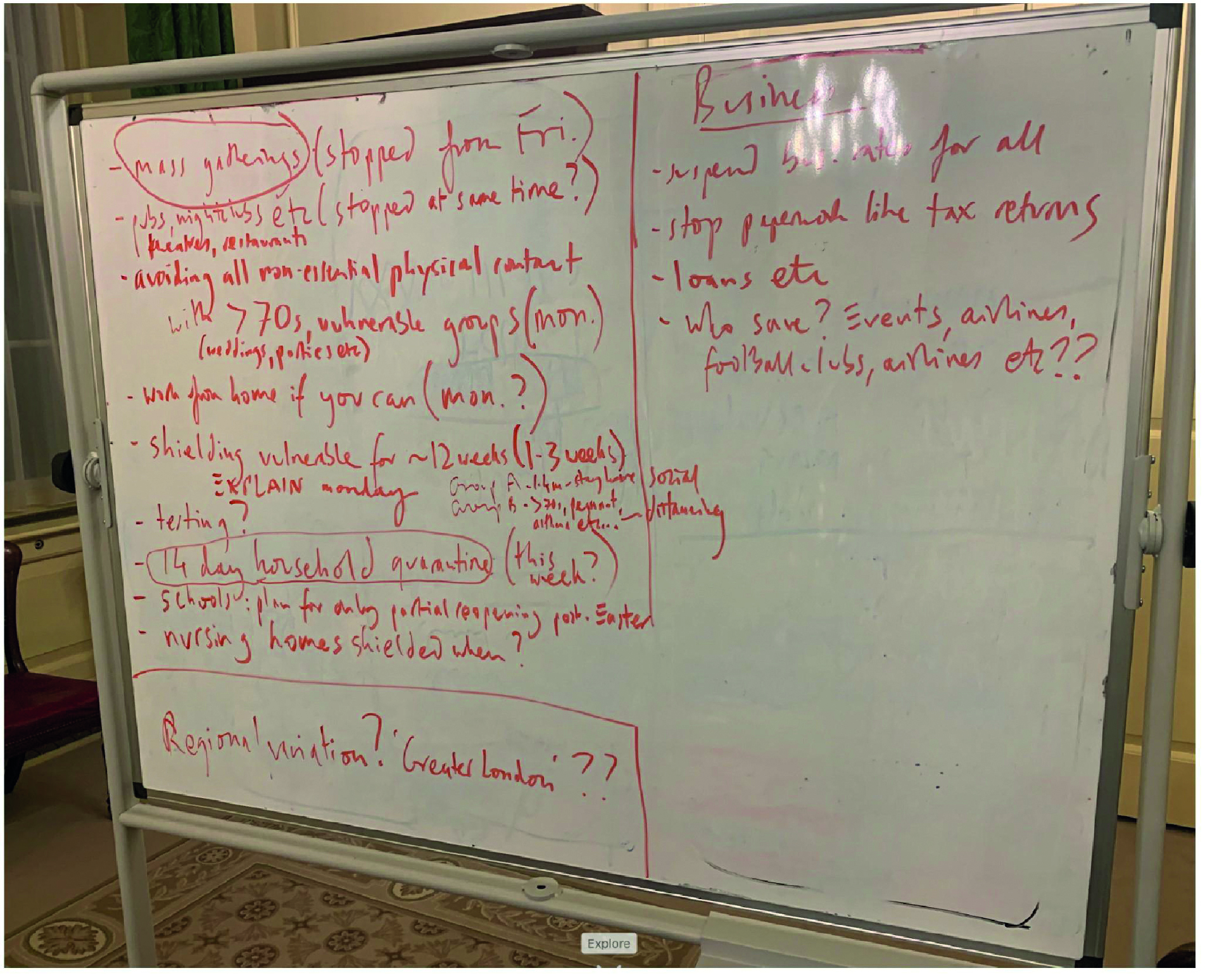

| Figure 8 | Notes on a whiteboard during the meeting at 10 Downing Street on 14 March 2020 |

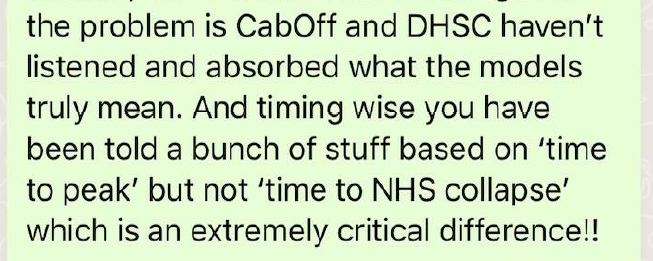

| Figure 9 | Message from Mr Cummings to Mr Johnson on 14 March 2020 |

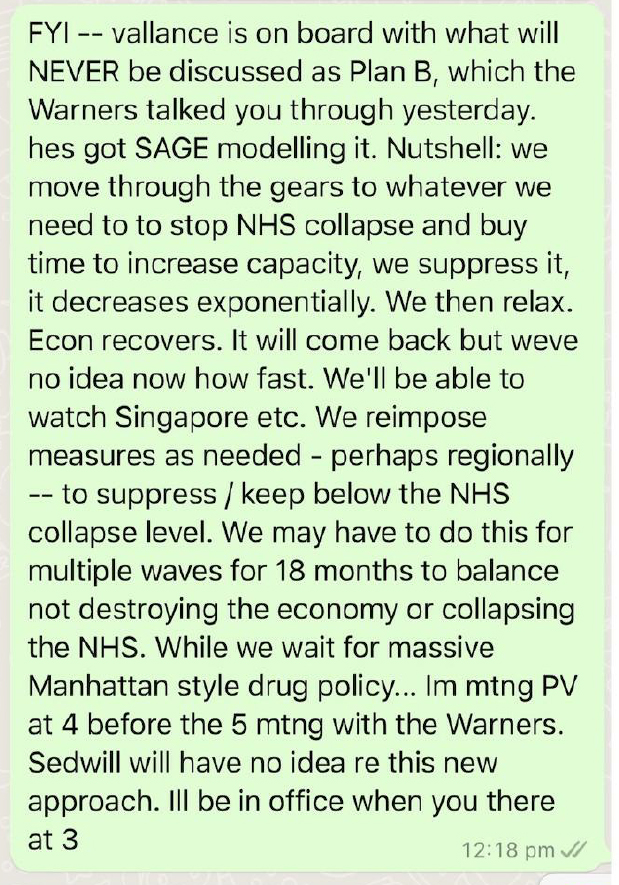

| Figure 10 | Message from Mr Cummings to Mr Johnson on 15 March 2020 |

| Figure 11 | Notes on a whiteboard during a ministerial meeting on 15 March 2020 |

| Figure 12 | Daily confirmed cases from 2 to 23 March 2020 across the UK |

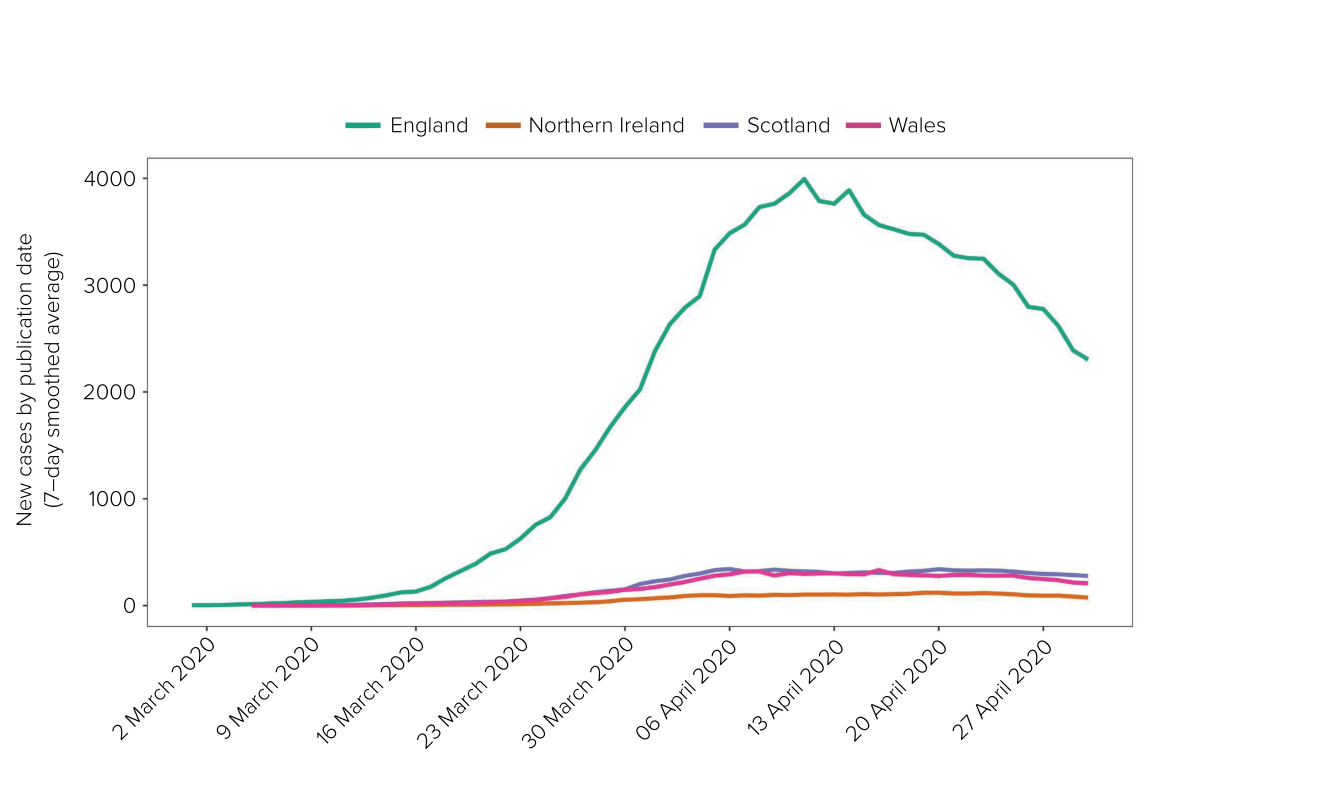

| Figure 13 | Daily confirmed cases from 1 March to 30 April 2020 across the UK |

| Figure 14 | Daily deaths per 100,000 population by date of death from 23 March to 13 July 2020 across the UK |

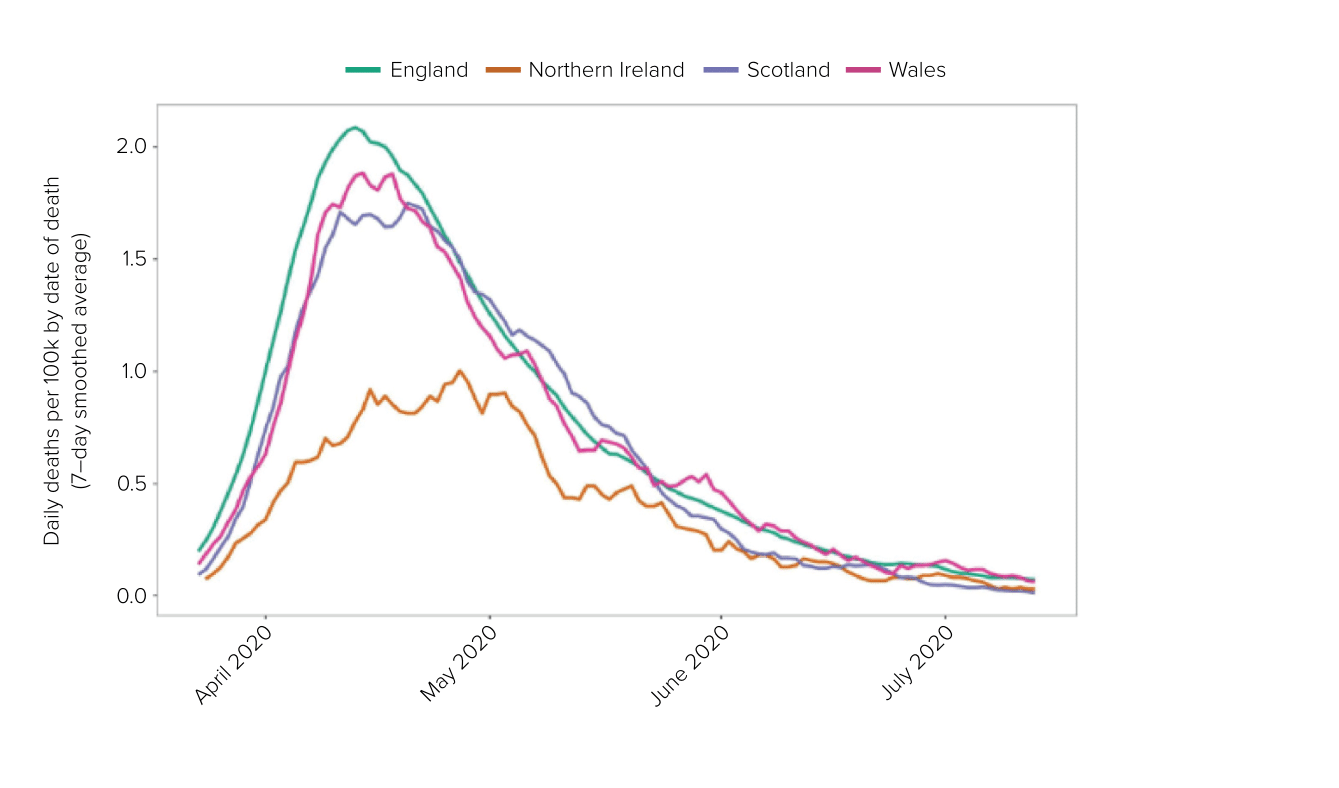

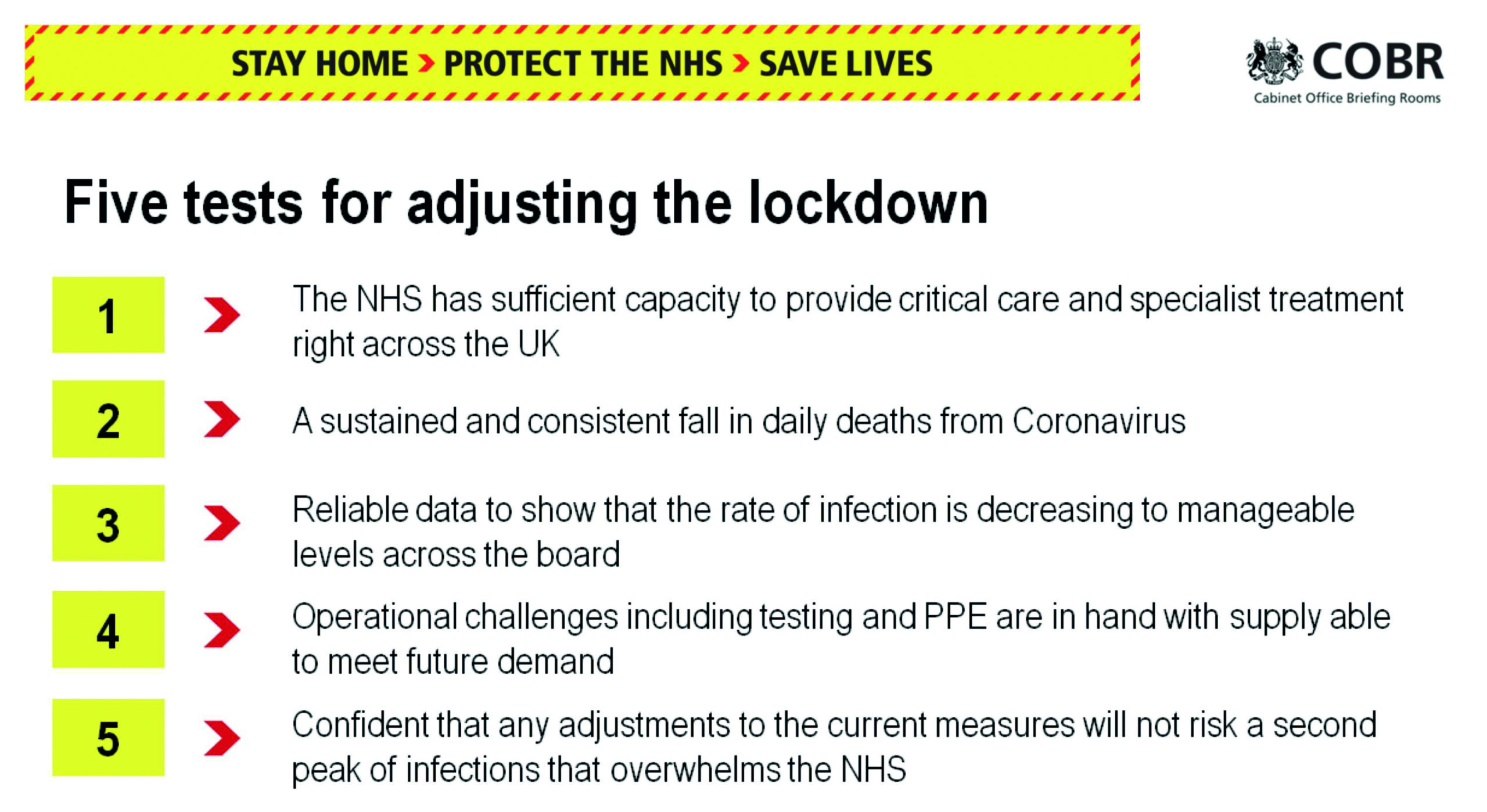

| Figure 15 | Five tests for adjusting the lockdown, 16 April 2020 |

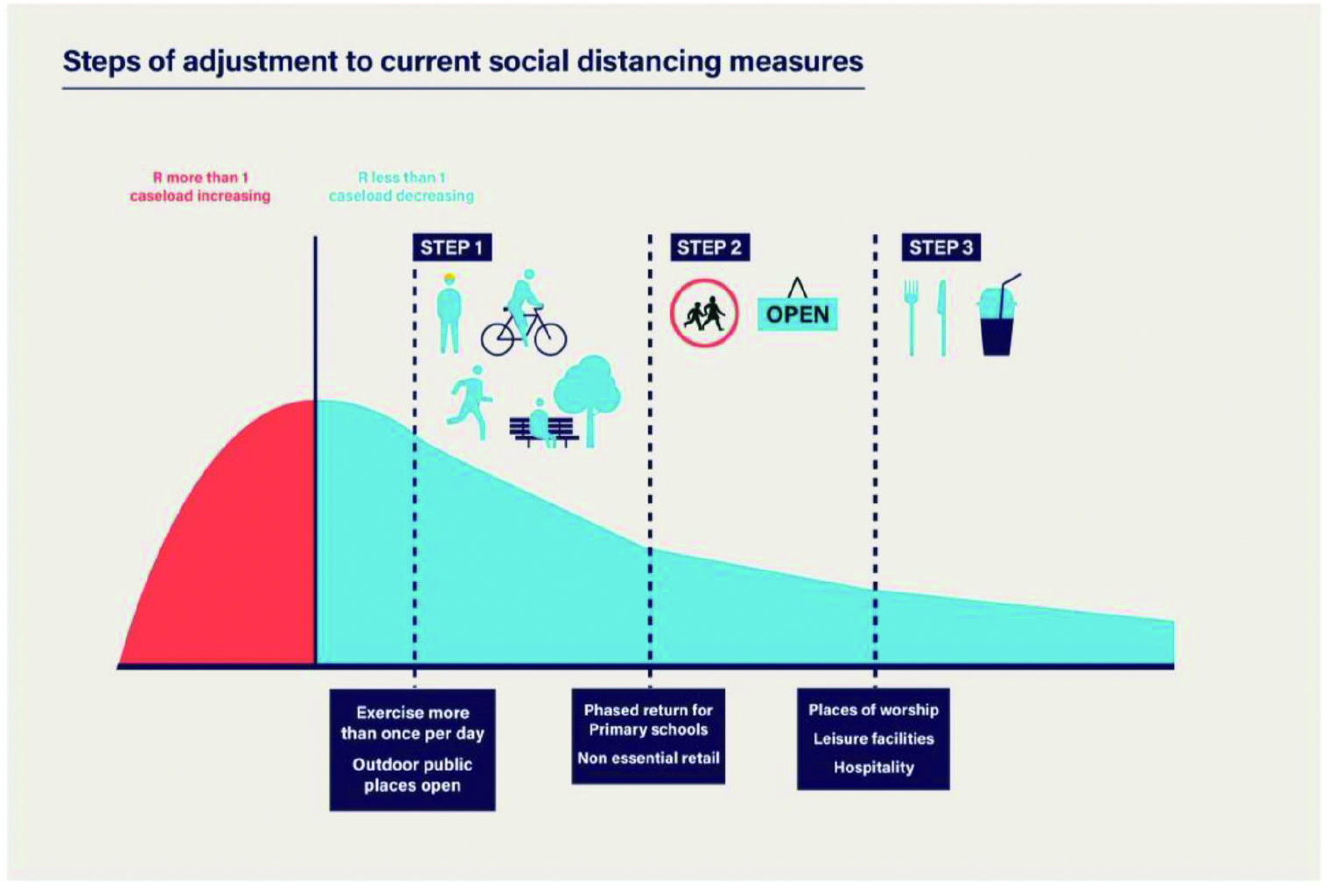

| Figure 16 | UK government steps of adjustment to current social distancing measures |

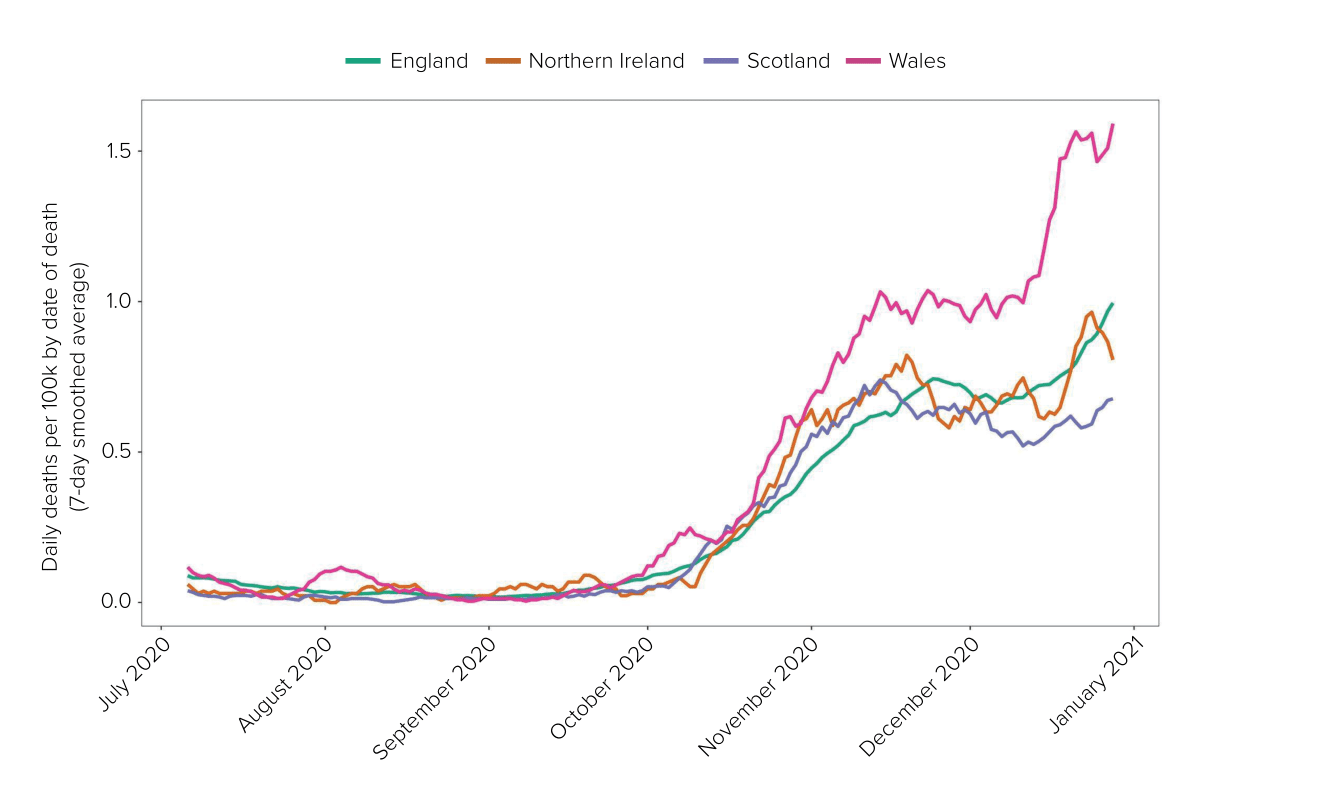

| Figure 17 | Daily deaths per 100,000 population by date of death from 6 July to 28 December 2020 across the UK |

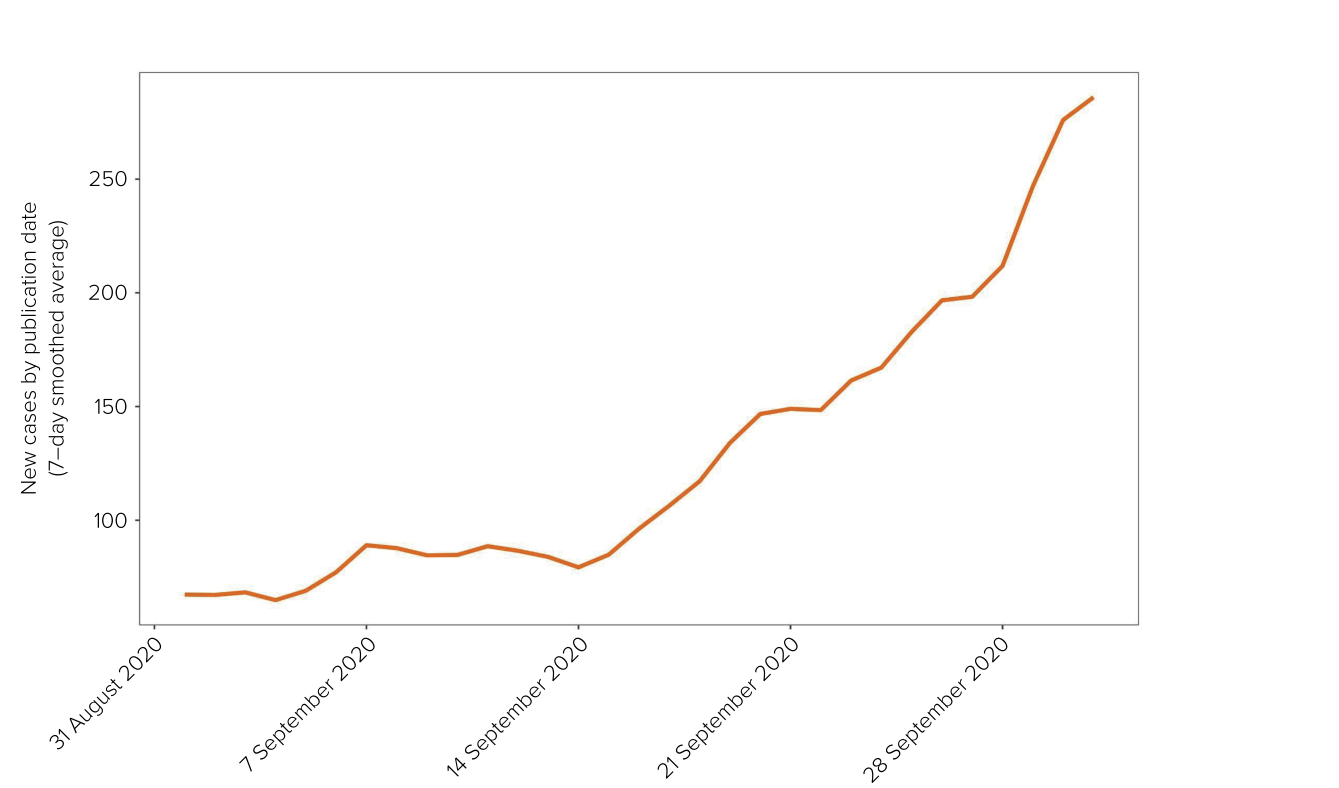

| Figure 18 | Increase in infections in Northern Ireland from 1 September to 1 October 2020 |

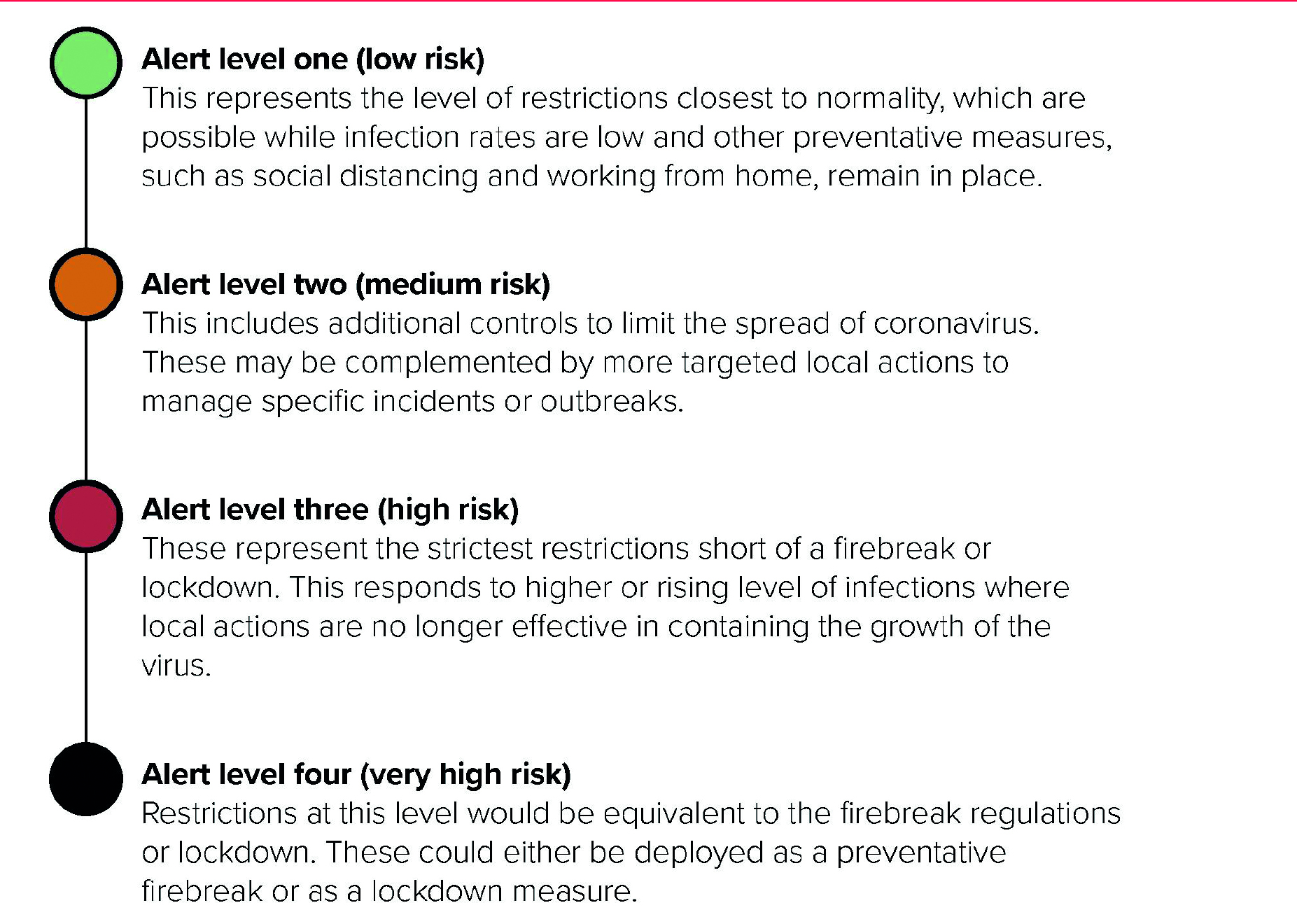

| Figure 19 | Alert levels in Wales, December 2020 |

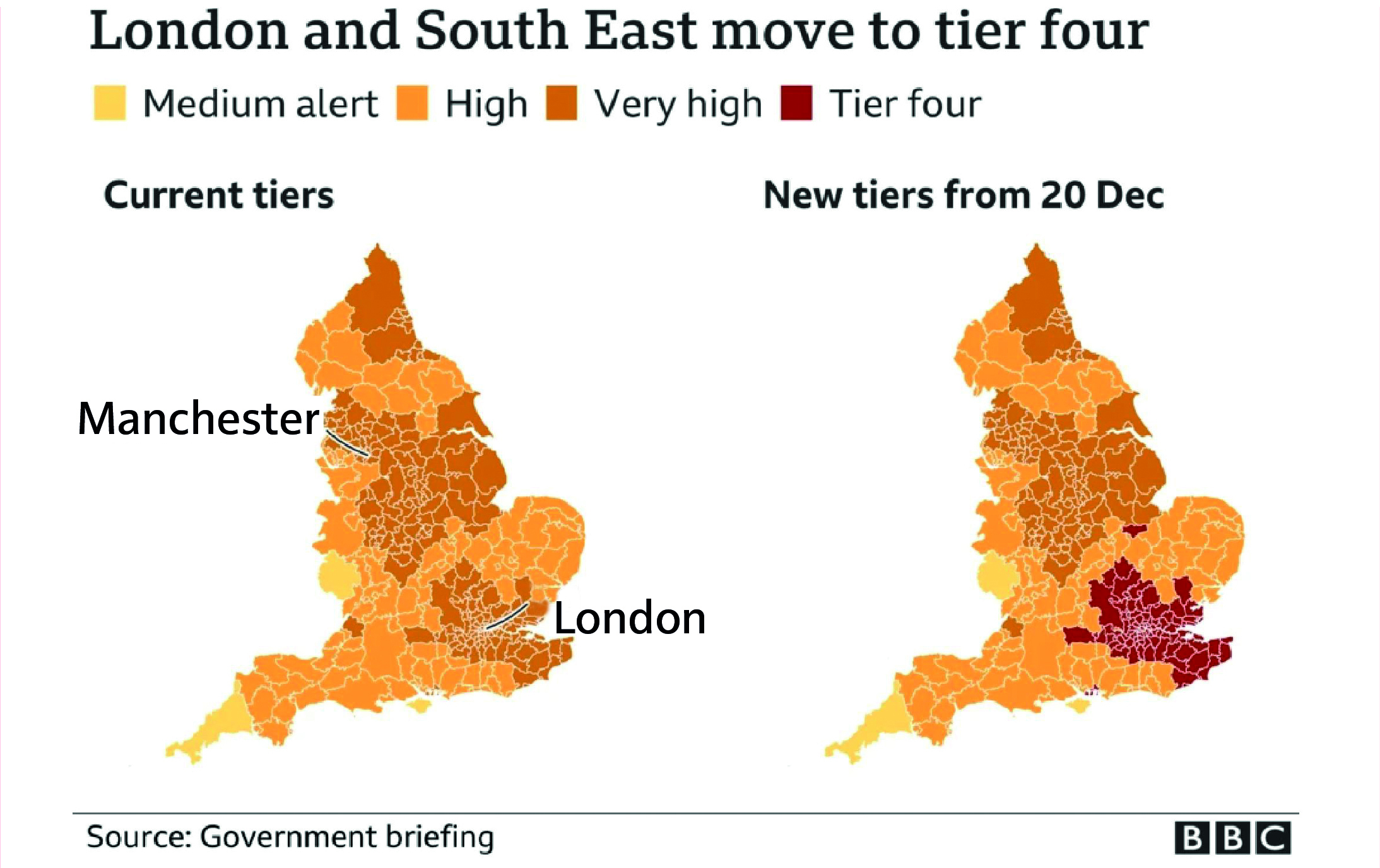

| Figure 20a | Tiers in England from 20 December 2020 |

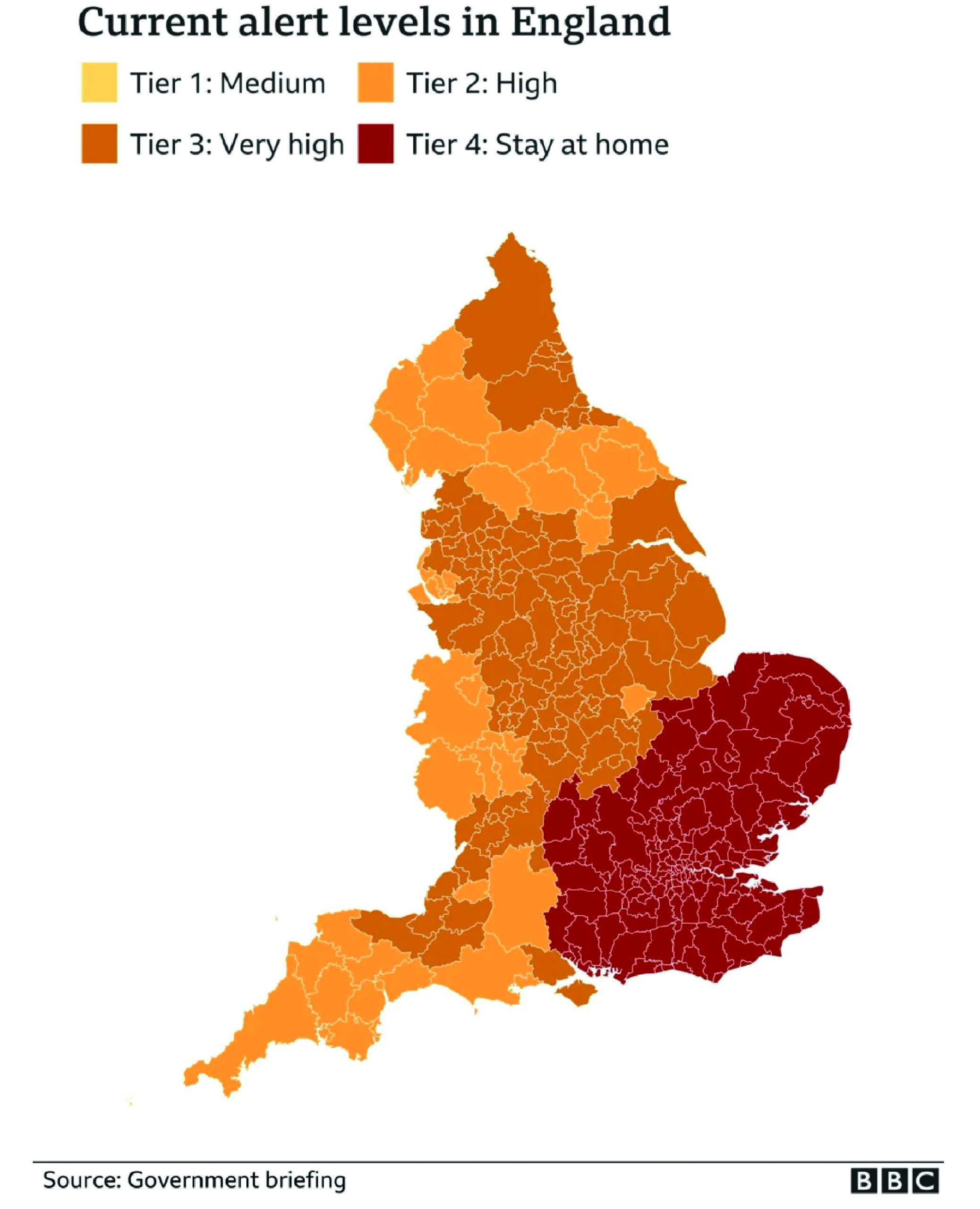

| Figure 20b | Tiers in England from 26 December 2020 |

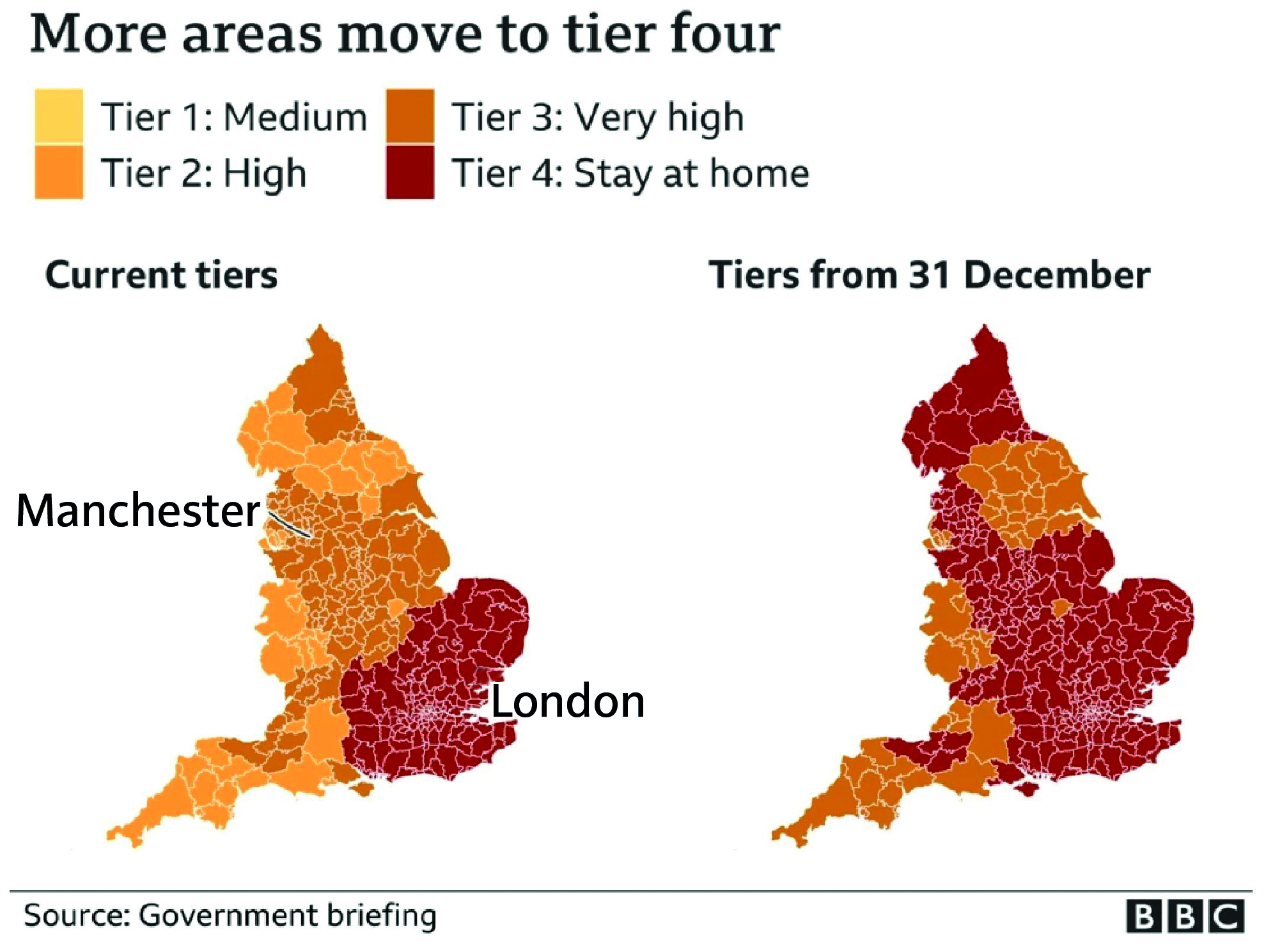

| Figure 20c | Tiers in England from 31 December 2020 |

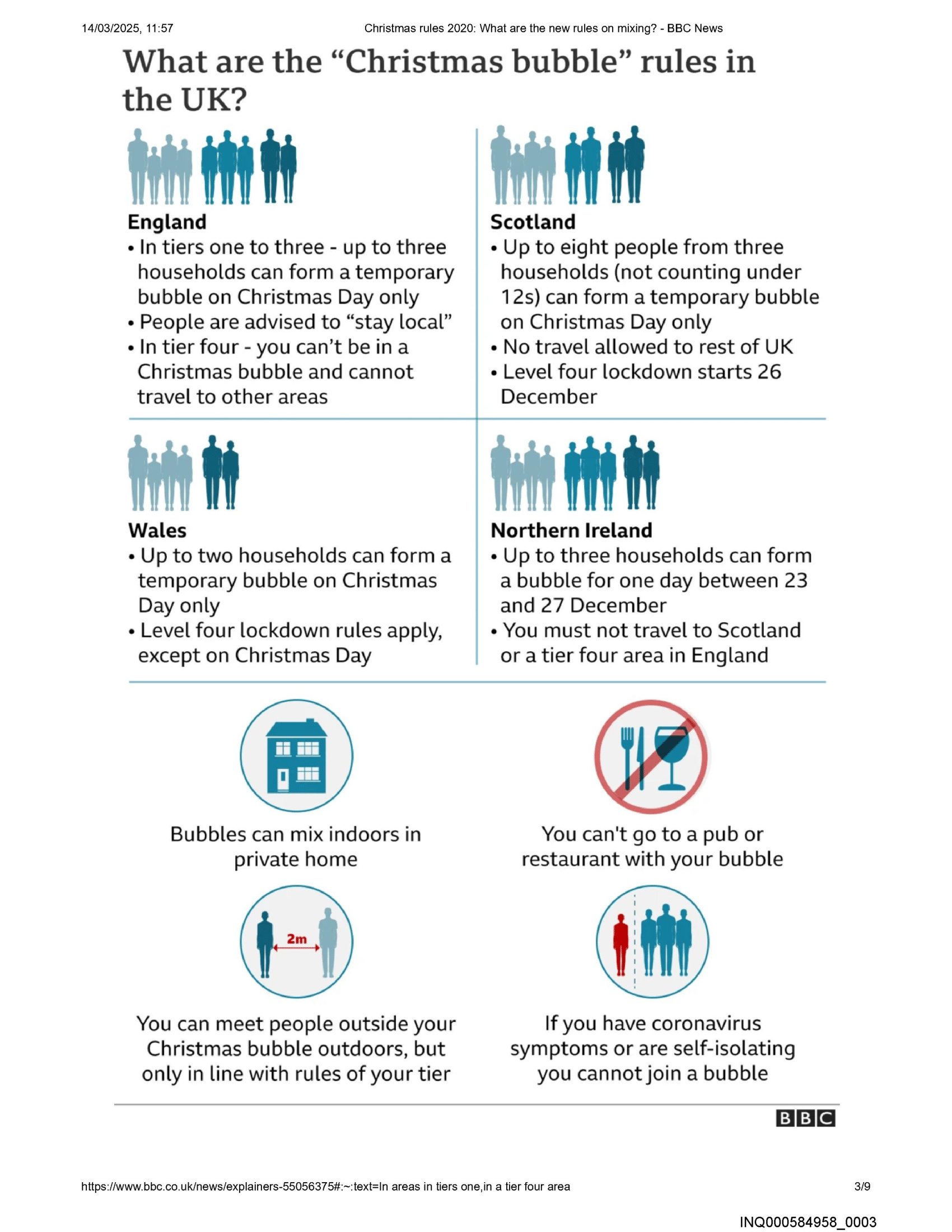

| Figure 21 | Revised rules for Christmas 2020 |

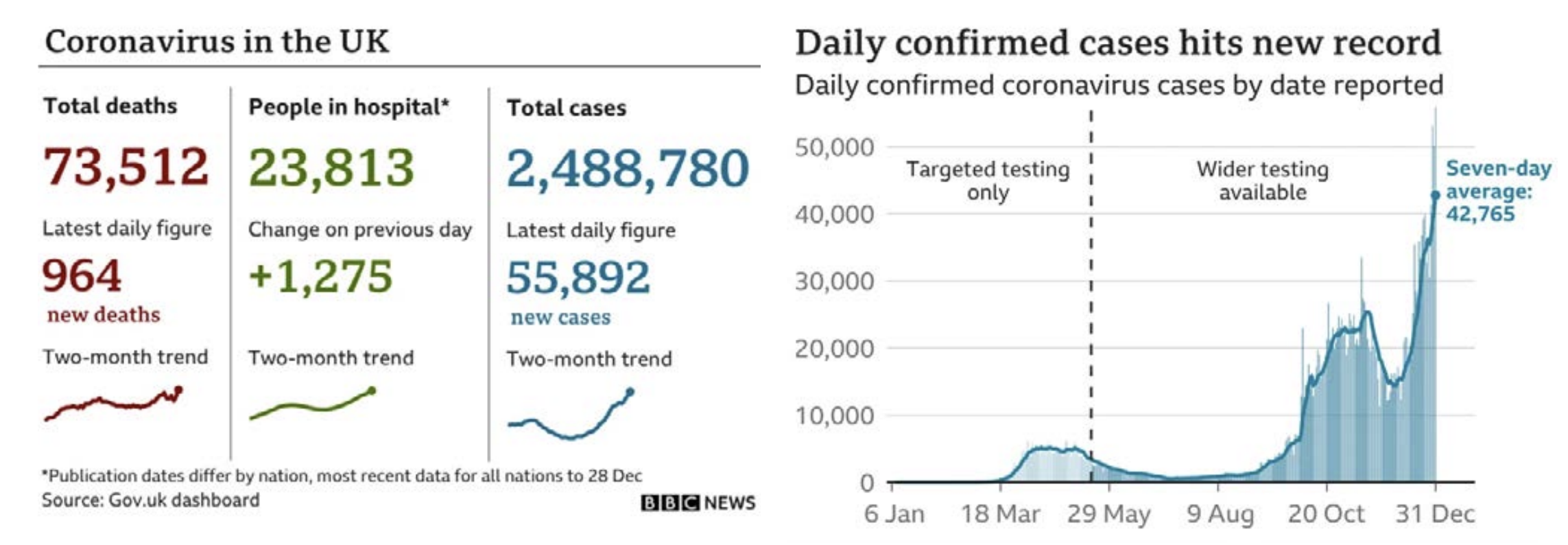

| Figure 22 | UK Covid-19 statistics at 31 December 2020 |

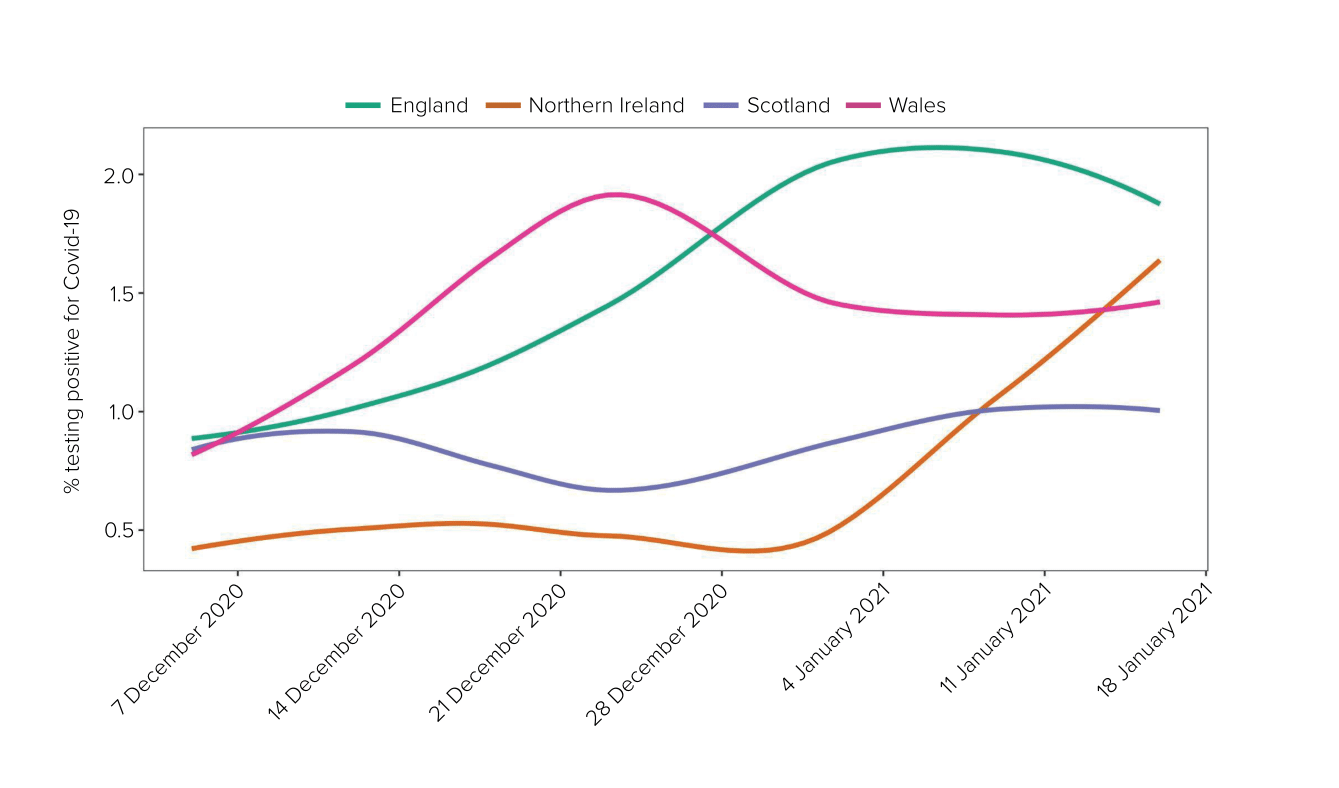

| Figure 23 | Estimated percentage of the population testing positive |

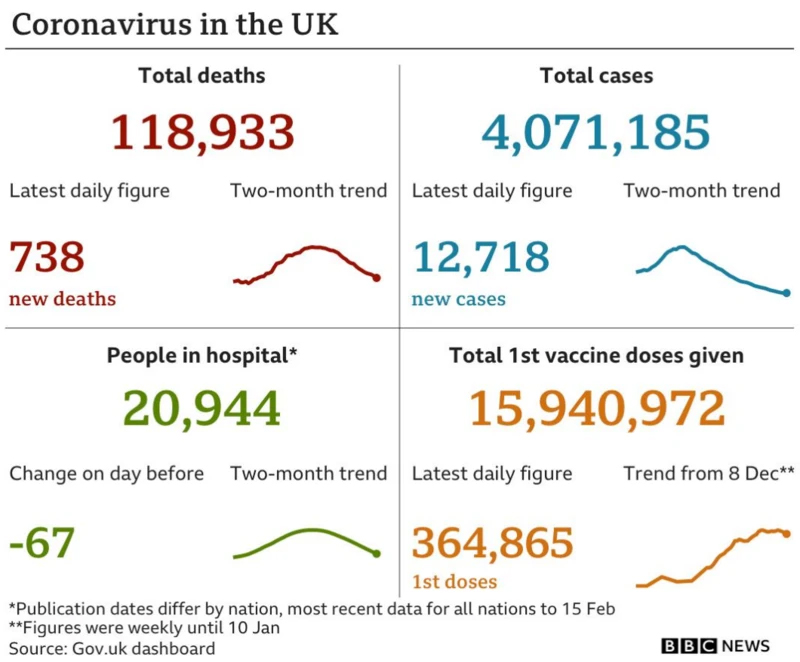

| Figure 24 | UK Covid-19 statistics at 15 February 2021 |

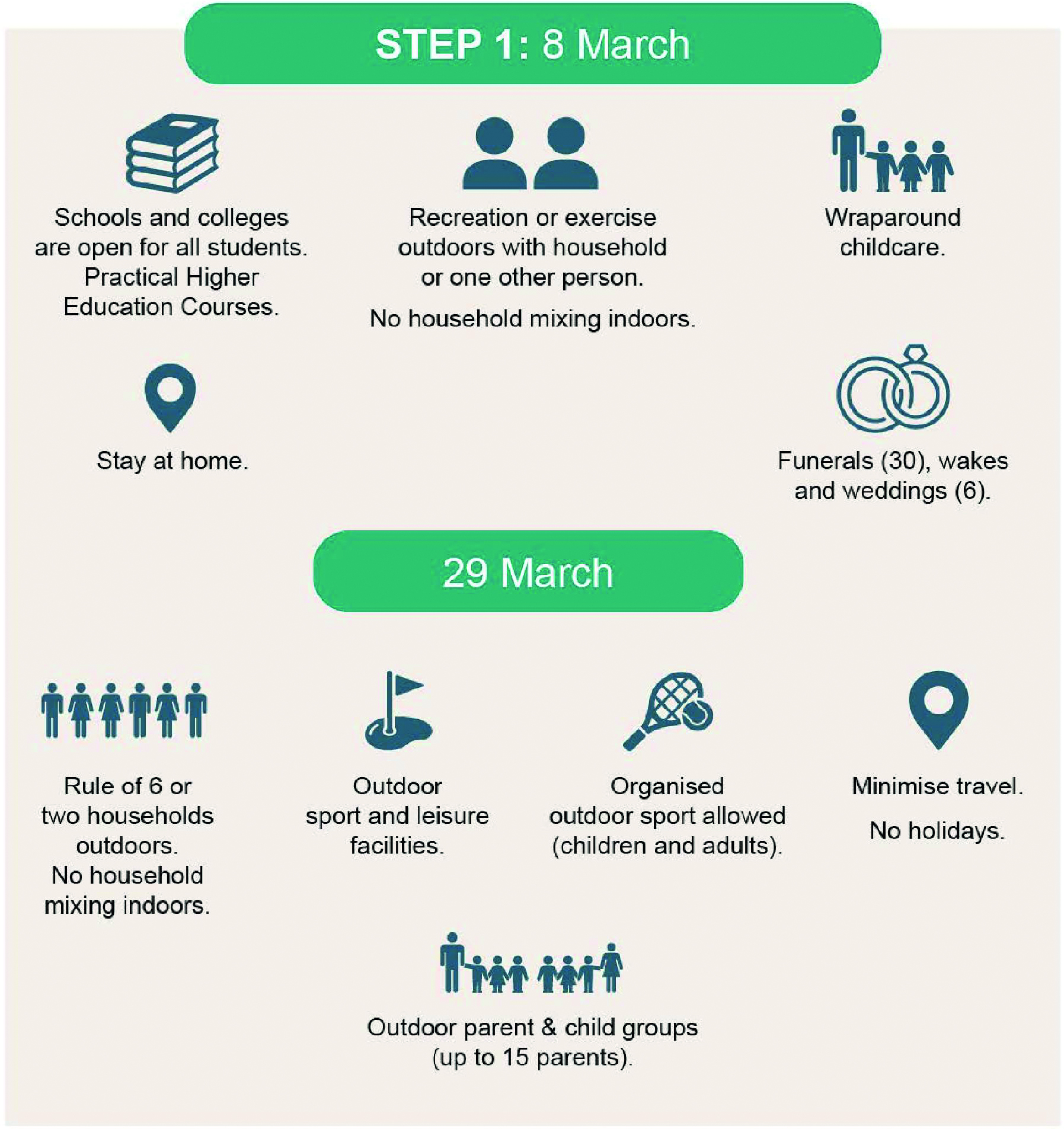

| Figure 25 | Steps in the COVID-19 Response – Spring 2021 roadmap, February 2021 |

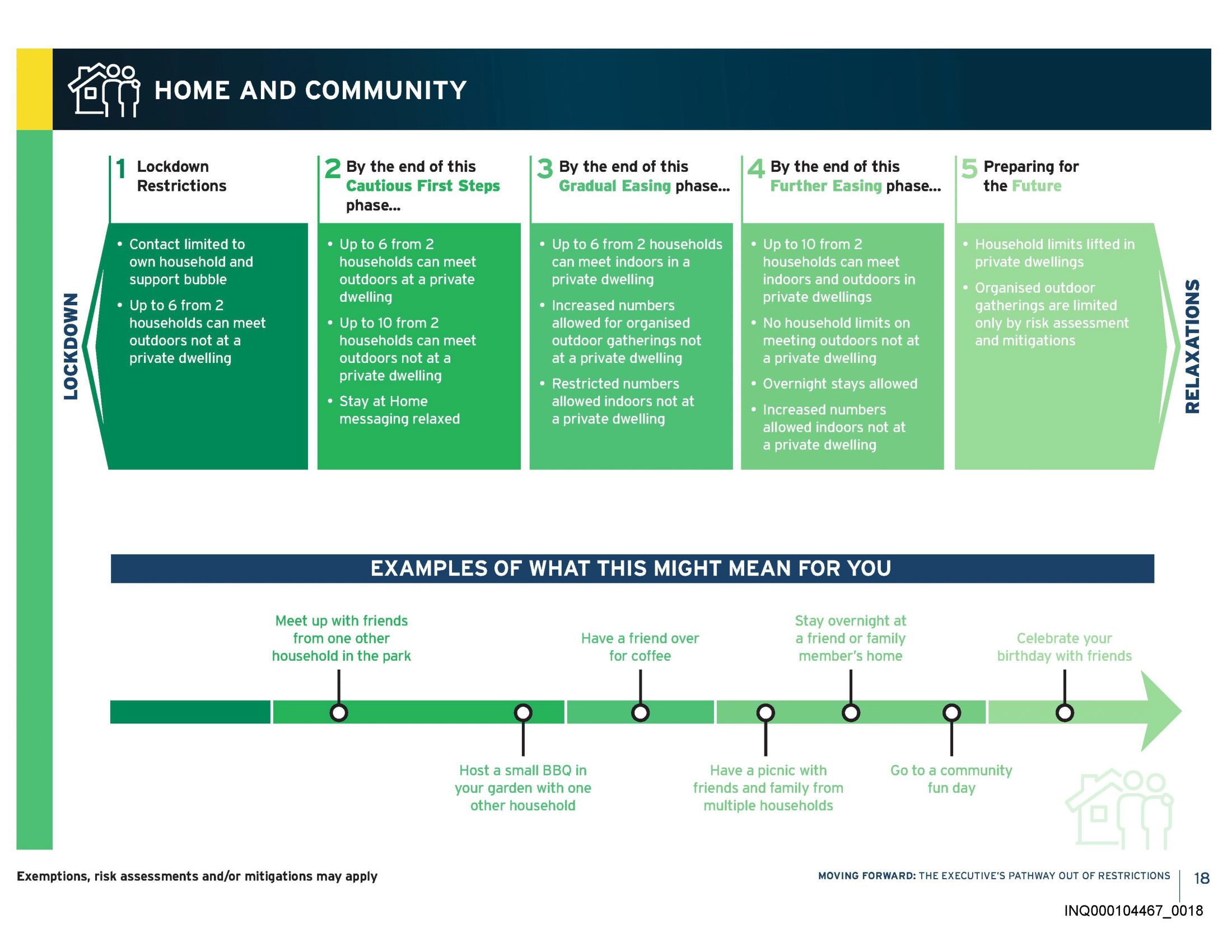

| Figure 26 | Extract from Moving Forward: The Executive’s Pathway out of Restrictions |

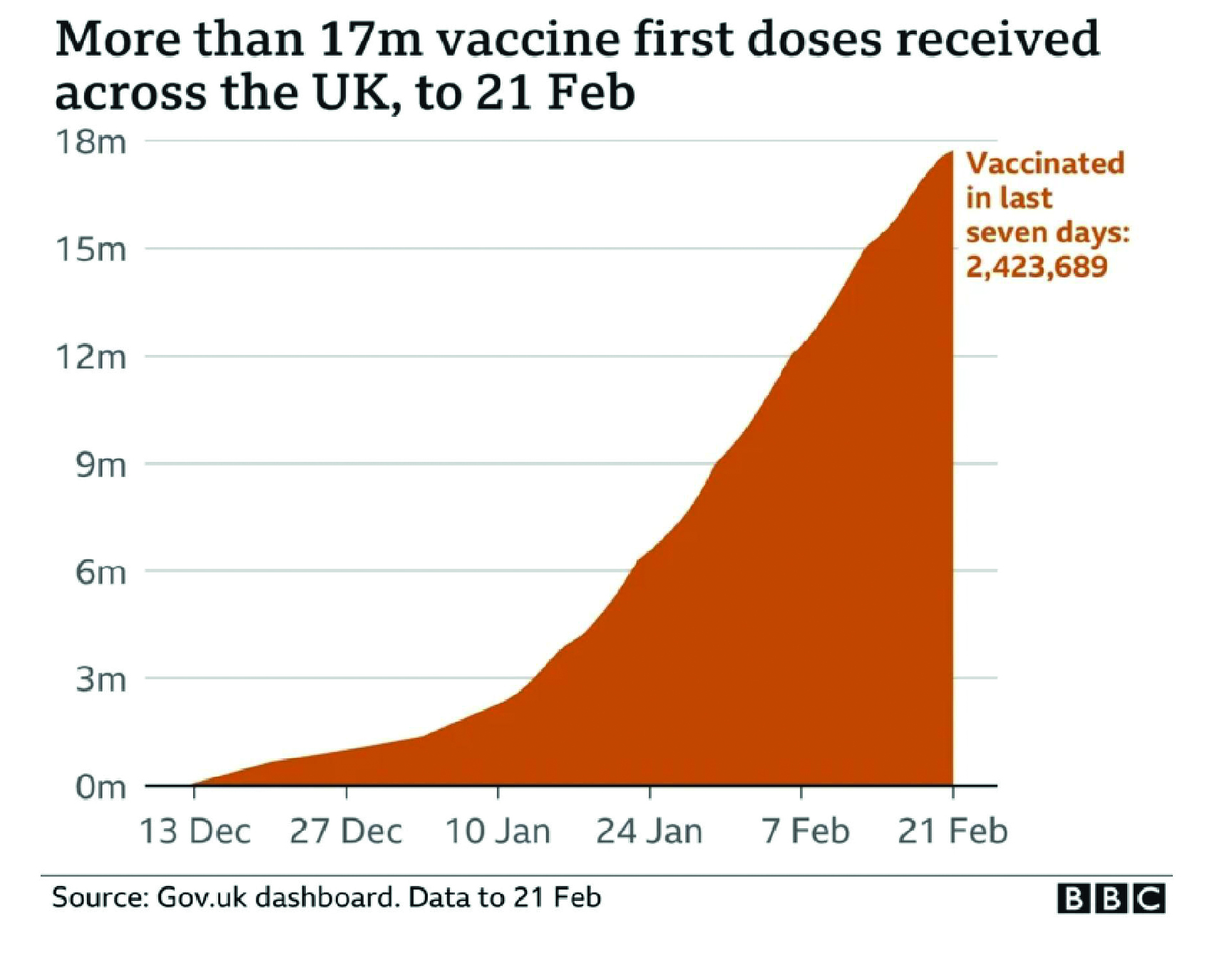

| Figure 27 | Vaccine doses across the UK, as at 21 February 2021 |

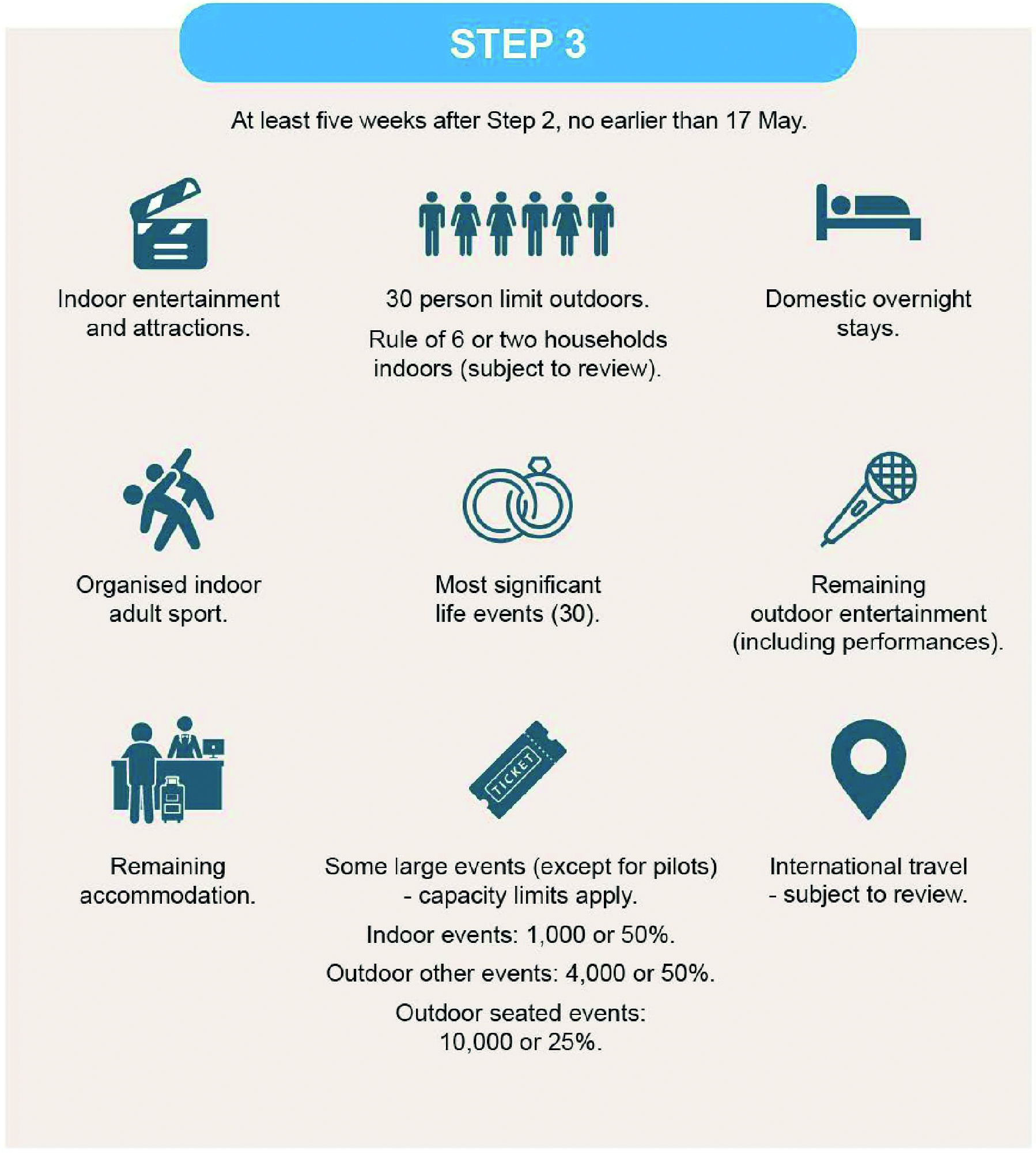

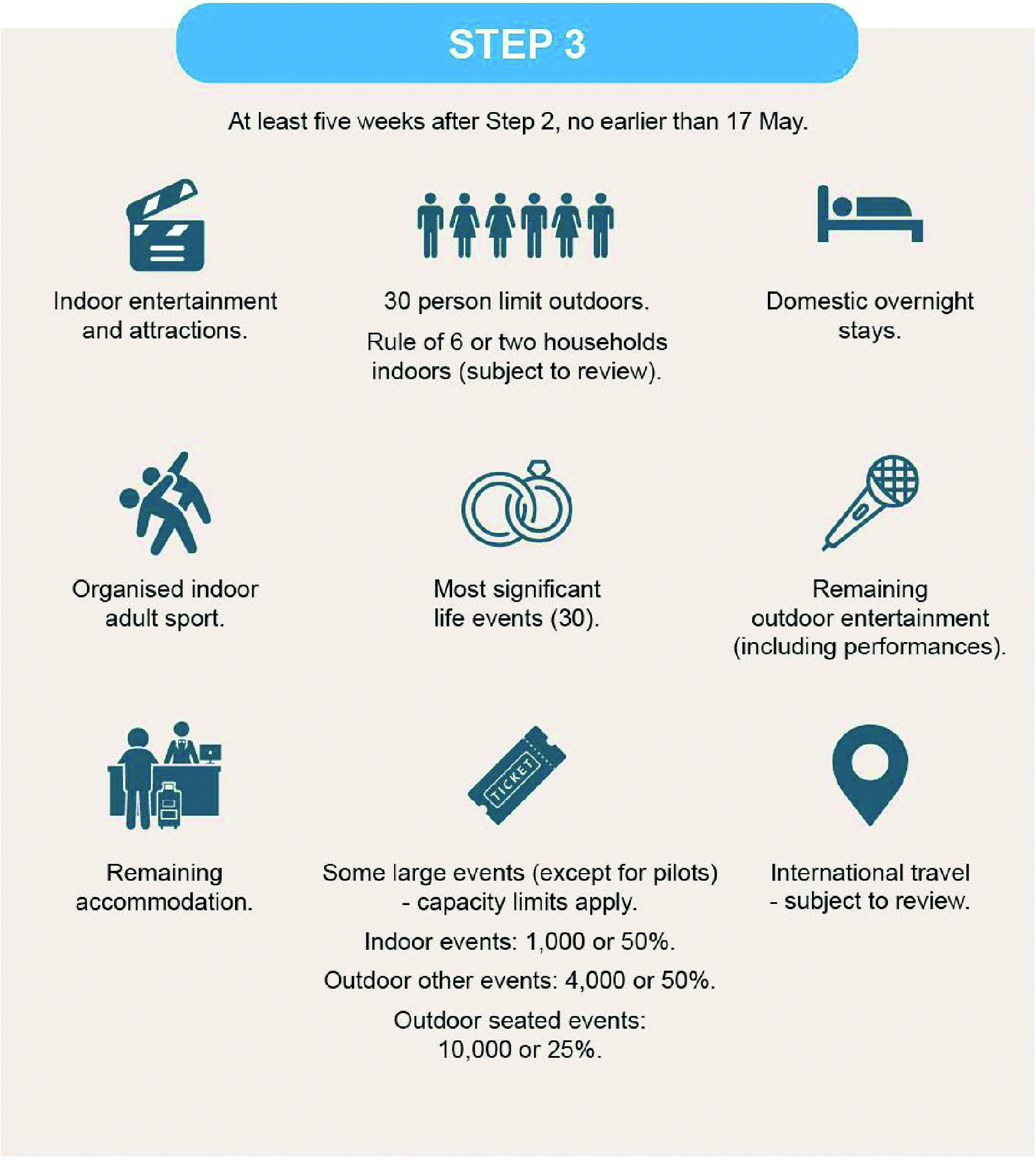

| Figure 28 | Step 3, COVID-19 Response – Spring 2021 roadmap |

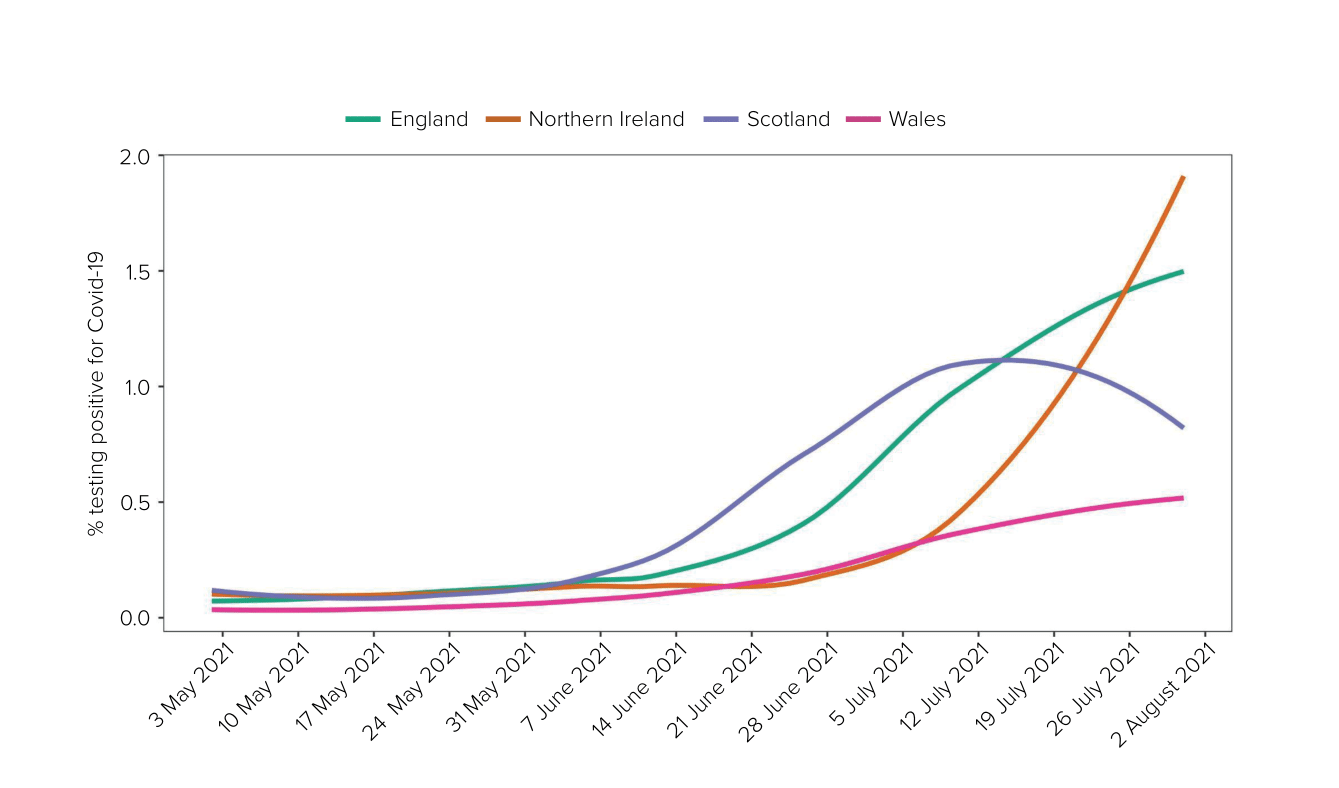

| Figure 29 | Estimated percentage of the population testing positive for Covid-19 from 1 May to 31 July 2021 across the UK |

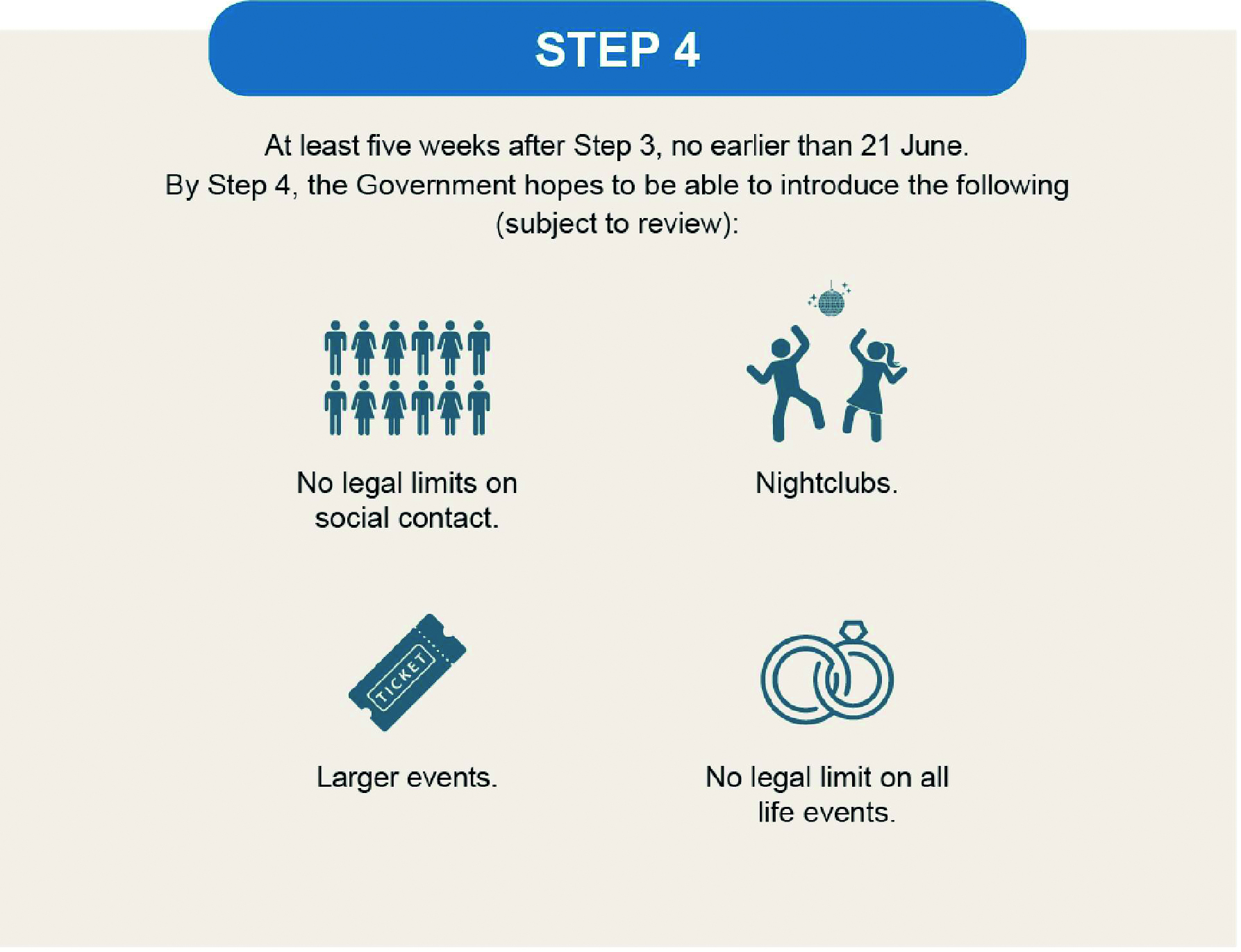

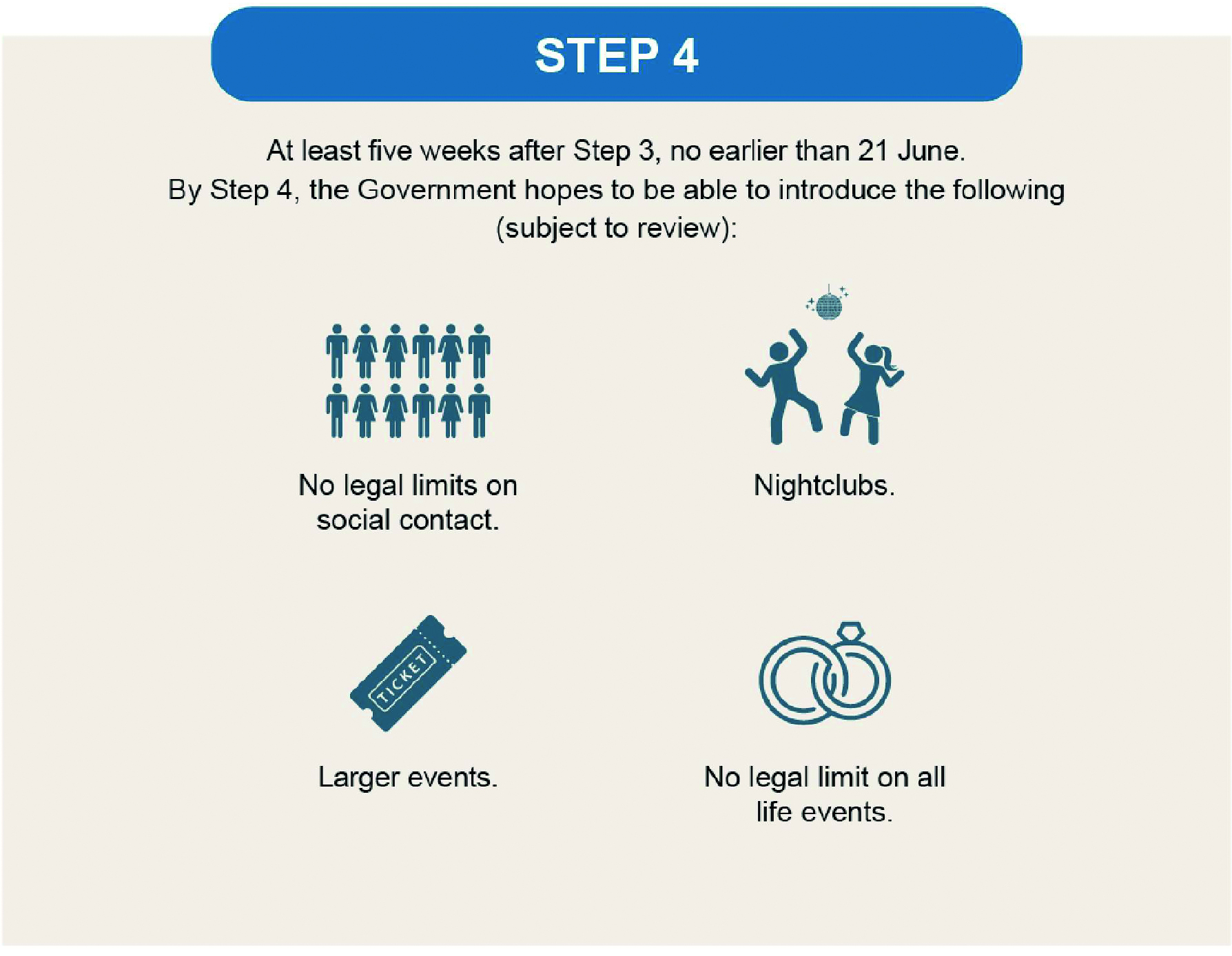

| Figure 30 | Step 4, COVID-19 Response – Spring 2021 roadmap |

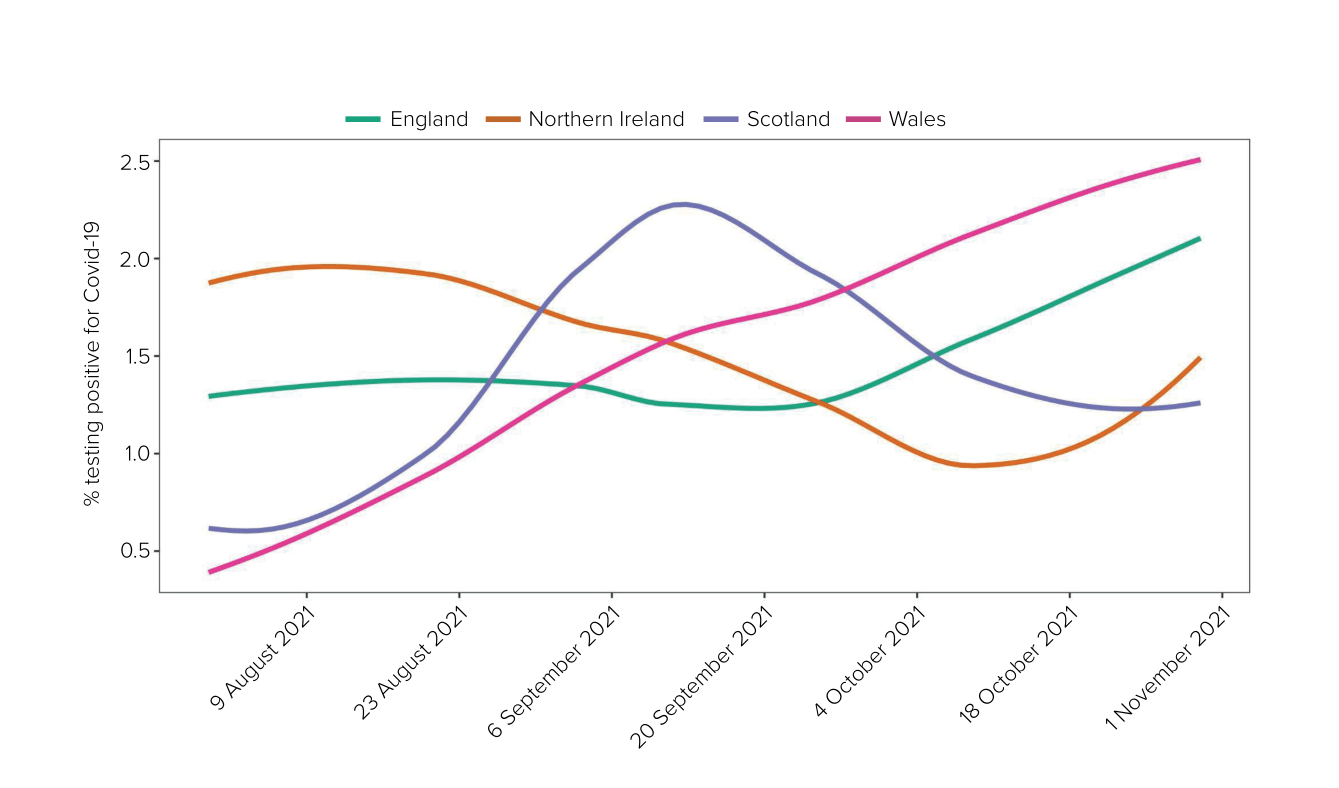

| Figure 31 | Alert levels in Wales in the summer of 2021 |

| Figure 32 | Estimated percentage of the population testing positive for Covid-19 from 1 August to 31 October 2021 across the UK |

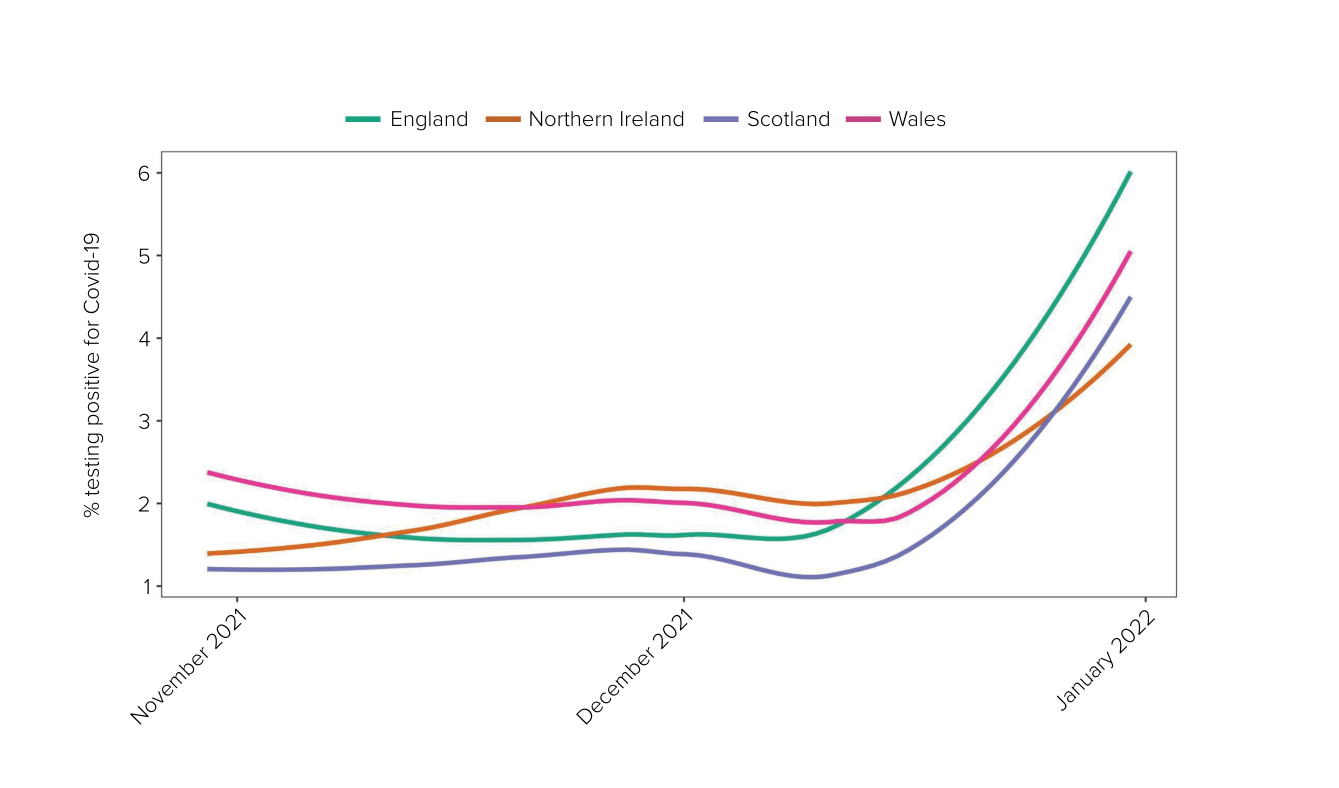

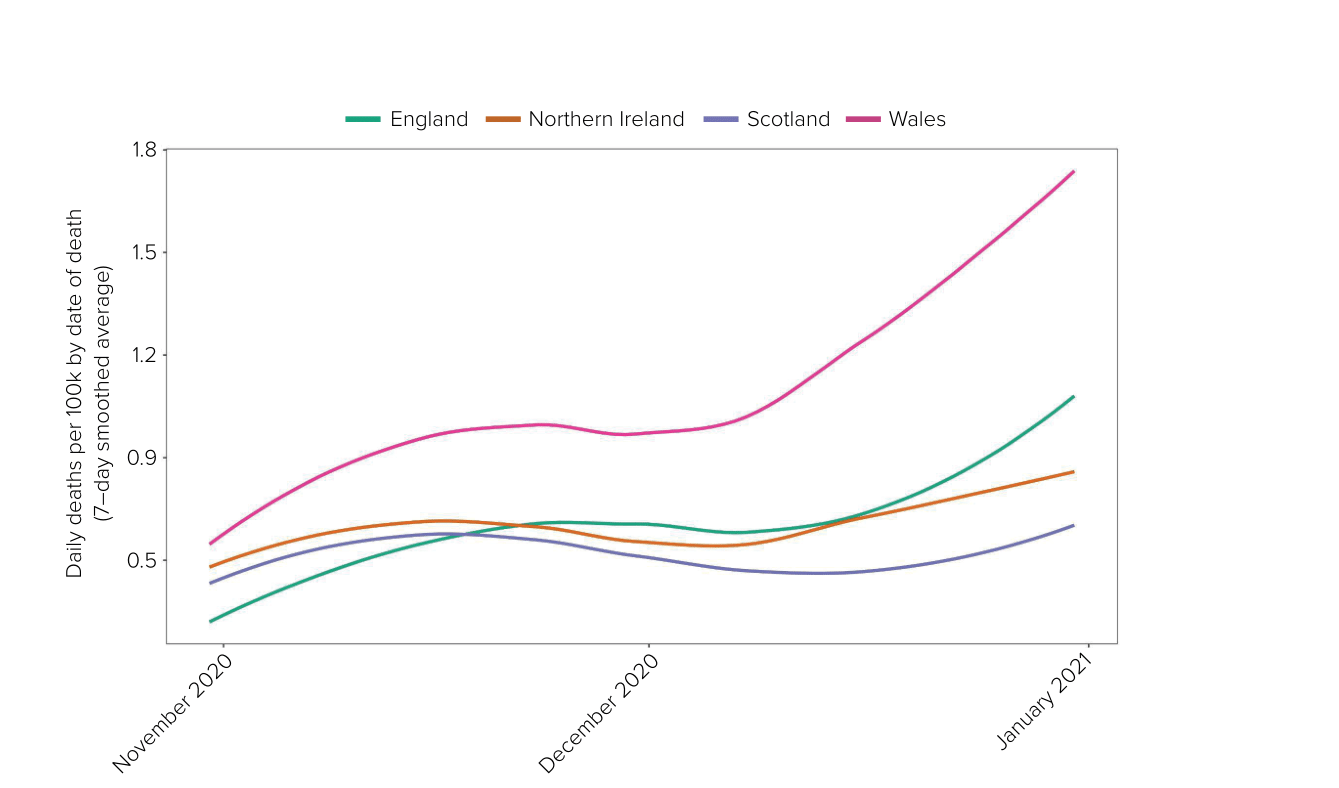

| Figure 33 | Estimated percentage of the population testing positive for Covid-19 from 31 October to 31 December 2021 across the UK |

| Figure 34 | Daily deaths per 100,000 population by date of death from 31 October to 31 December 2021 across the UK |

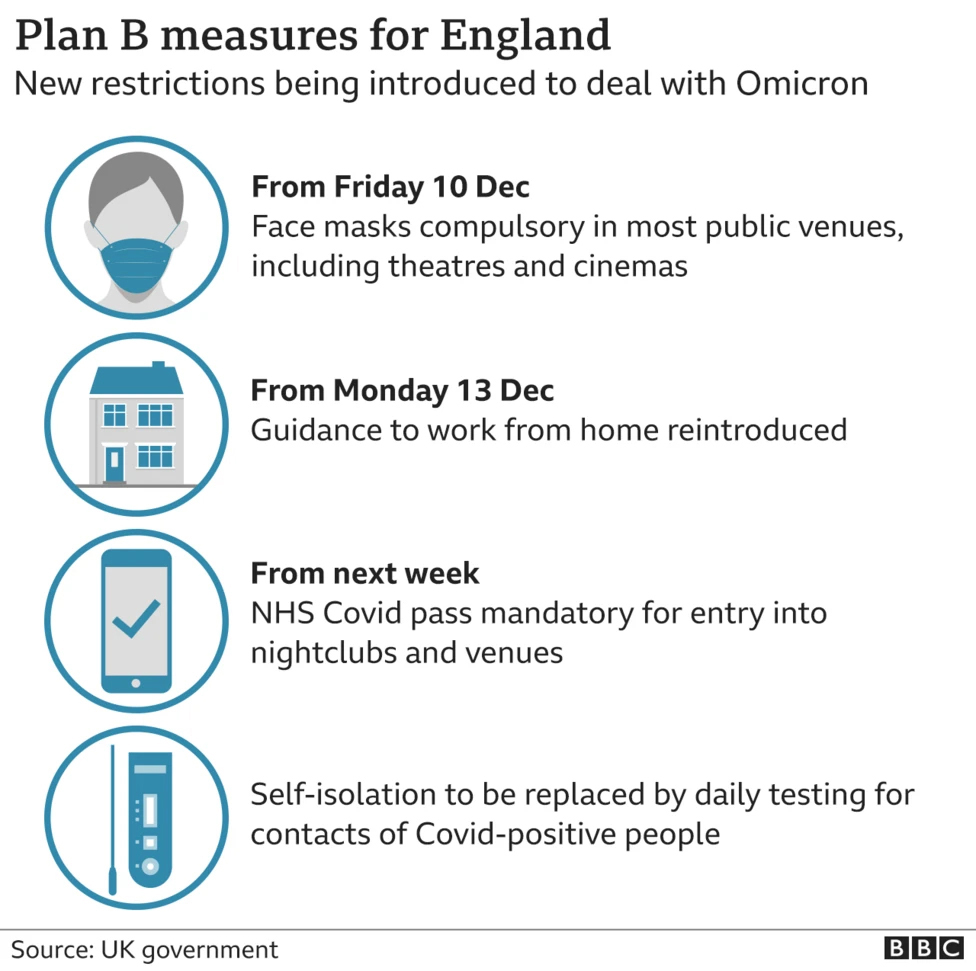

| Figure 35 | Plan B measures announced on 8 December 2021 |

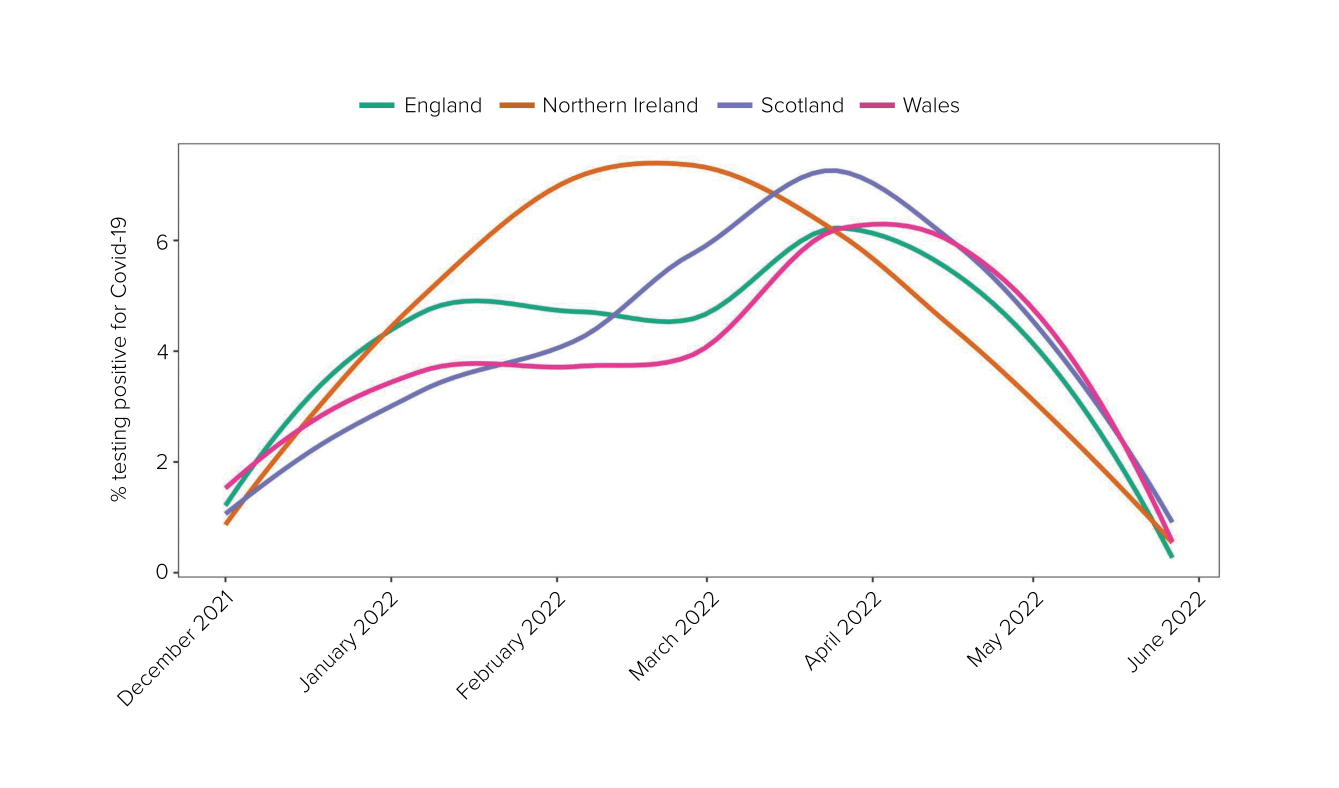

| Figure 36 | Estimated percentage of the population testing positive for Covid-19 from 1 December 2021 to 1 June 2022 across the UK |

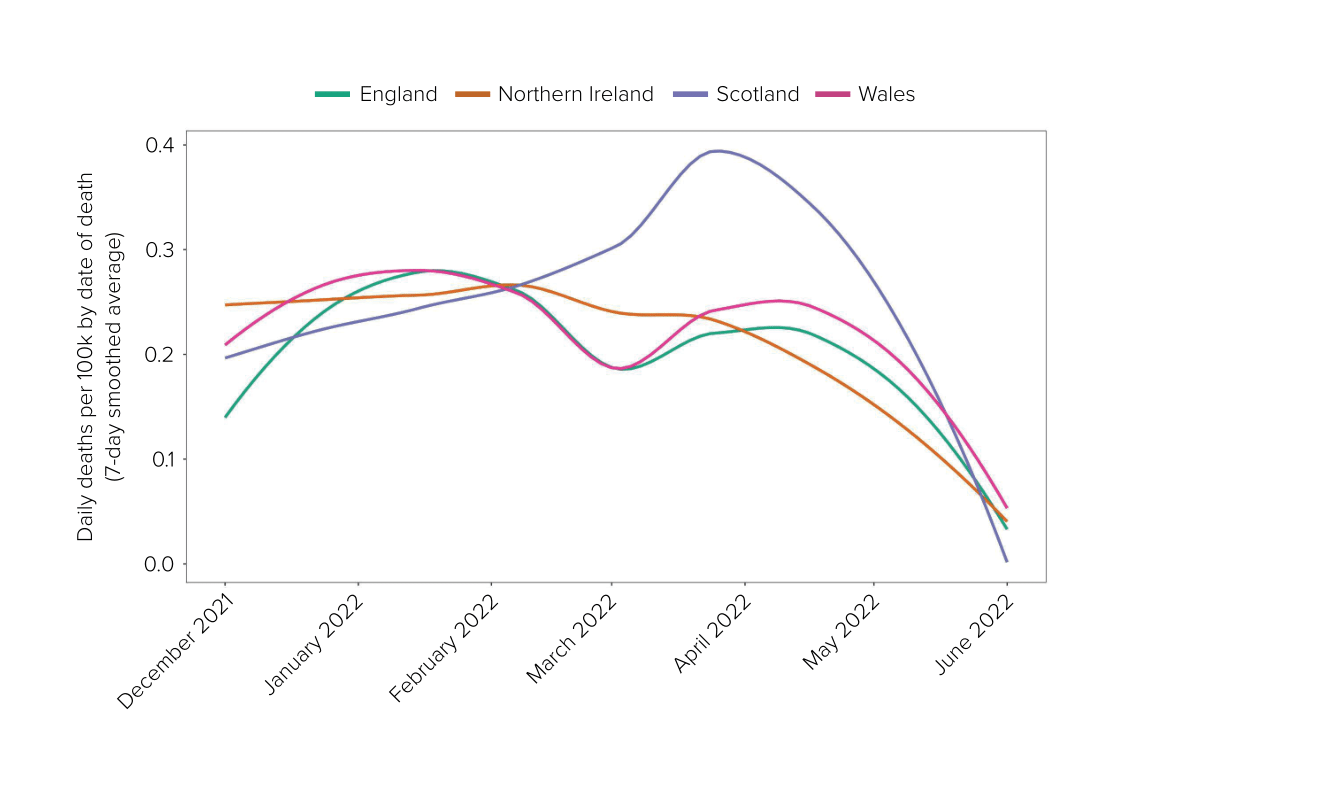

| Figure 37 | Daily deaths per 100,000 population by date of death from 1 December 2021 to 1 June 2022 across the UK |

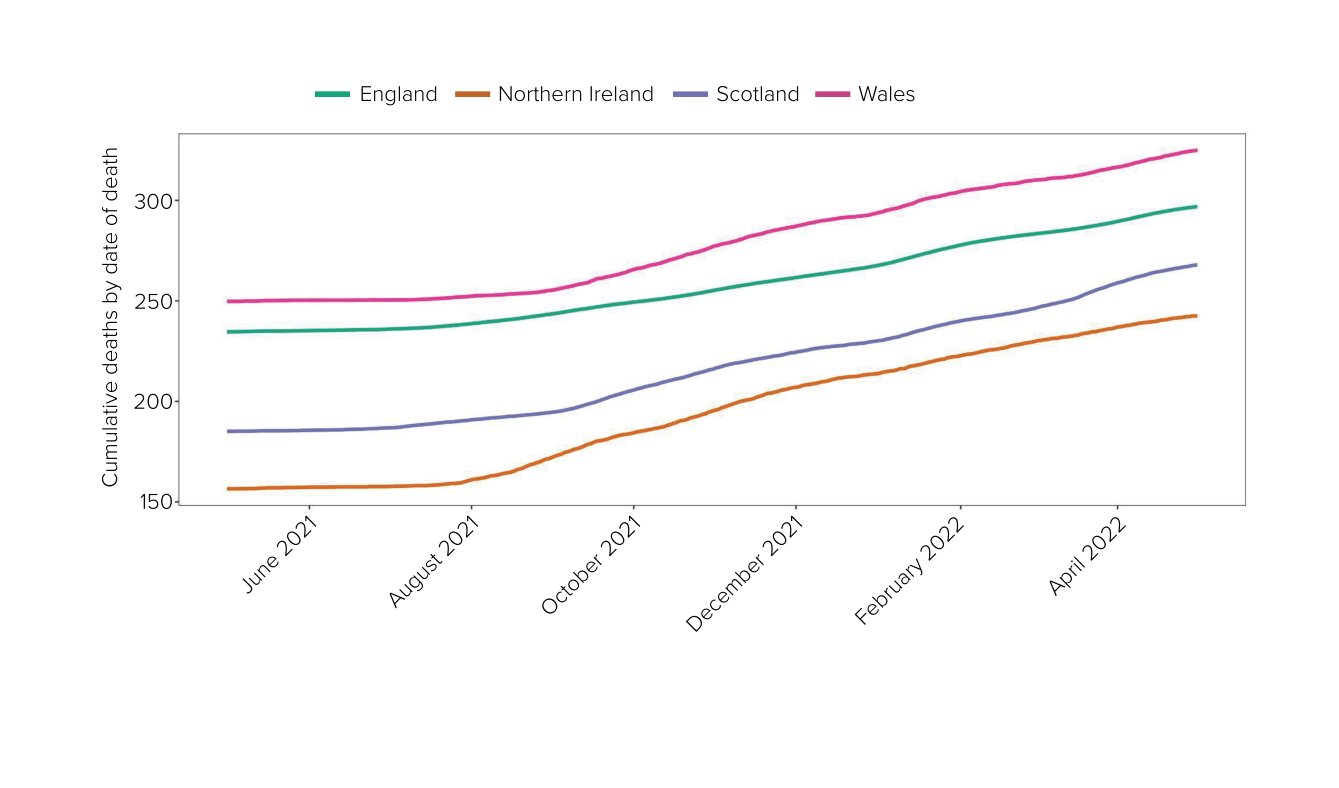

| Figure 38 | Cumulative daily deaths per 100,000 by date of death from May 2021 to May 2022 across the UK |

| Table | Description |

|---|---|

| Table 1 | Summary of potential response strategies |

| Table 2 | Interventions considered by SAGE (presented by the Cabinet Secretariat to COBR on 12 March 2020) |

| Table 3 | The rule of six by nation, September 2020 |

| Table 4 | Combined estimate of R and the growth rate in the UK, four nations and English NHS regions, 23 September 2020 |

Introduction by The Rt Hon the Baroness Hallett DBE

The Covid-19 virus spread around the world rapidly and caused untold misery and suffering. The number of deaths across the UK for which the virus was responsible – calculated by whether Covid-19 is mentioned on the death certificate – is now over 230,000. This appalling loss of life resulted from the virus spreading across the UK in three successive waves. The devastating socio-economic consequences resulted both from the virus and from the decisions taken to respond to it.

This, the second report of the UK Covid-19 Inquiry, focuses on those decisions.

As democratically elected leaders, politicians were entitled to draw their own conclusions as to how to balance the ethical, public health, social and economic challenges posed by Covid-19. In this Report, I have considered whether their decisions were reasonable and justifiable in light of the information that was then known, or which ought to have been known, to determine if things could have been done better and to learn lessons for the future.

In doing so, I bear very much in mind that, in trying to stem the spread of the virus, politicians in the UK government and devolved administrations were faced with unenviable choices. There were few, if any, easy decisions for them to make. The decisions to impose stringent social restrictions, including most obviously the lockdown decisions, gave rise to agonising dilemmas and were highly controversial. They were also taken under conditions of extreme pressure and often without access to data or a full understanding of the epidemiological position. Such an understanding is vital to any response to a pandemic.

Most importantly, politicians across the UK found themselves having to take decisions in the context of the UK lacking resilience and being ill prepared.

In its first report, relating to Module 1 on the resilience and preparedness of the UK, the Inquiry examined the state of the UK’s central structures and procedures for pandemic emergency preparedness, resilience and response. It concluded that the UK was ill prepared for dealing with a catastrophic emergency, let alone the coronavirus pandemic that actually struck. In particular, it found that there were fatal strategic flaws underpinning the assessment of the risks faced by the UK. The UK government’s sole pandemic strategy, from 2011, was outdated and lacked adaptability.

As a result, there was a damaging absence of focus on the measures, interventions and infrastructure required in the event of a pandemic – in particular, a system that could be scaled up to test, trace and isolate. The Inquiry recommended fundamental reform of the way in which the UK government and devolved administrations prepare for whole-system civil emergencies.

Such reform is vital. Had the UK been better prepared, fewer lives would have been lost, the socio-economic costs would have been substantially reduced and some of the decisions politicians had to take would have been far more straightforward.

The decisions that politicians were forced to take were further complicated by the UK devolution settlements. This was primarily a health emergency and health is a devolved matter, but three of the nations of the UK form a single epidemiological unit (Great Britain). The other, Northern Ireland, forms an epidemiological unit with the Republic of Ireland. Whatever steps each government took, they were bound to be affected by the decisions taken elsewhere in the UK and by constant cross-border travel. In addition, the devolved administrations were generally reliant on the UK government for funding to support their emergency response.

Initially, the UK government and devolved administrations followed the same path in responding to the pandemic but, in the summer of 2020, they began to diverge. This might not have been surprising, given the devolution settlement and the different characteristics of the four nations, but it did lead to difficulties for the people of the UK as they sought to comply with restrictions that varied around the UK – and it caused political controversy. This Report will examine those differences in approach and, where appropriate, compare them.

Some past public inquiries have provided definitive accounts of every aspect of the particular disaster, tragedy, other momentous event or government policy into which they were charged to inquire. However, as I observed in the Introduction to the Inquiry’s first report, the Covid-19 pandemic – and the response to it from the UK government and devolved administrations – was the most complex and multi-layered emergency to have struck the UK in peacetime. No inquiry, however large or however long, could possibly or sensibly inquire into every part of it. This Report does not seek to address every relevant decision or provide a historical record of everything that happened. It is focused on the key issues and decisions taken during the almost two and a half years of the pandemic, in order to identify the critical lessons to be learned for future pandemics or other civil emergencies.

Other modules of this Inquiry and their reports will consider specific aspects of the governments’ response in more detail. At the time of publication of this Report, there have been public hearings in Module 3 (Impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on healthcare systems in the four nations of the UK), Module 4 (Vaccines and therapeutics), Module 5 (Procurement), Module 6 (Care sector), Module 7 (Test, trace and isolate) and Module 8 (Children and young people). Hearings will take place shortly in relation to Module 9 (Economic response) and Module 10 (Impact on society, which has a particular focus on key workers, the most vulnerable, the bereaved, mental health and wellbeing).

The speed and thoroughness with which the momentous events and decisions have been examined, from the emergence of Covid-19 in January 2020 until the final restrictions were lifted in May 2022, reflect a mammoth undertaking for the Module 2 (UK government), 2A (Scottish Government), 2B (Welsh Government) and 2C (Northern Ireland Executive) teams.

During the investigation phase, there was an extensive and complex process of obtaining more than 2 million potentially relevant documents from a wide range of sources. This material was then examined by the Inquiry team and in excess of 180,000 documents were deemed to be relevant. These were disclosed to the 53 Core Participants to assist them in their preparation for the public hearings, which took place over 69 days and during which 166 witnesses were examined.

This reflects the enormously hard work of a large number of people, and I wish to express my gratitude to all those who have given so much of their time and resources to assisting the Inquiry. In particular, I am very grateful to the Core Participants and their legal teams, especially the groups representing bereaved people, for their helpful contributions to the Inquiry process. I would also like to thank the teams (both secretariat and legal) in Modules 2, 2A, 2B and 2C, without whose hard work, diligence and dedication the hearings and this Report would not have been possible.

Finally, I should like to thank those who have given evidence and those who have contributed to the Inquiry’s listening exercise, Every Story Matters, and to the moving films played at each hearing about the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on them and their loved ones. They have shown great courage. Their accounts not only help me and inform the Inquiry’s work, but also serve as a constant reminder of why the work of this Inquiry is so important.

The Rt Hon the Baroness Hallett DBE

20 November 2025

Voices

Five days after Daddy went into hospital we had to get the police to break into my mum’s house because she was unconscious in bed. She was rushed to the same hospital and she would test positive when she got there. My dad died on the 10th of May. The day we buried Daddy, we were waiting for a phone call because that was the day they thought Mummy was going to die. But she died the next day. So we buried them three days apart.”¹

I feel that my mother was getting more and more nervous going into the second lockdown. I feel the Government were on TV every day talking about all these different things and there was no equality for her as an elderly lady. The elderly were not considered. It was a case of ‘keep away from the elderly and vulnerable to protect them’ meanwhile other people were in and out of each other’s bubbles and houses. There was no consideration for the elderly. I feel they were just numbers. My mum caught covid and died in the hospital.”²

[My mother] said ‘No I’m too afraid to go to the hospital, you know, if i haven’t got it and it’s just a really, really bad flu, then I’m going to end up with it, I don’t want to be on my own’ she said. So she was too afraid to go to the hospital.”³

I think I immediately found it very difficult to grieve. Not in the traditional sense, in terms of the funeral, obviously that was not available to us but I found it very hard emotionally to feel the – to go through the natural emotional process of grieving, because I think what was blocking me was that I felt very strongly that his death was not an inevitability.”⁴

Executive summary

This Report concerns the core political and administrative decision-making across the UK in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, drawing on the work of four of the Inquiry’s modules: Module 2 (UK), Module 2A (Scotland), Module 2B (Wales) and Module 2C (Northern Ireland). This has provided the Inquiry with the opportunity to compare and contrast the different choices made by the four governments in responding to the same emergency and to identify the most important lessons for responding to future UK-wide emergencies.

The Inquiry finds that the response of the four governments repeatedly amounted to a case of ‘too little, too late’. The failure to appreciate the scale of the threat, or the urgency of response it demanded, meant that – by the time the possibility of a mandatory lockdown was first considered – it was already too late and a lockdown had become unavoidable. That these same mistakes were repeated later in 2020 is inexcusable. While the nationwide lockdowns of 2020 and 2021 undoubtedly saved lives, they also left lasting scars on society and the economy, brought ordinary childhood to a halt, delayed the diagnosis and treatment of other health issues and exacerbated societal inequalities. The Covid-19 lockdowns only became inevitable because of the acts and omissions of the four governments. They must now learn the lessons of the Covid-19 pandemic if they are to avoid lockdowns in future pandemics.

Key events from January 2020 to May 2022

The emergence of Covid-19 (Chapter 2)

The initial response to the pandemic was marked by a lack of information and a lack of urgency. When the first cases of Covid-19 had been confirmed outside China, the significant degree of scientific uncertainty – in particular, whether there was sustained person-to-person transmission and whether the virus could be transmitted by individuals without symptoms (asymptomatic transmission) – meant that the level of risk that the virus posed was not fully appreciated.

Once the scientific community and the scientific advisers for each nation became aware that the virus had spread from China, and that it was causing substantially more cases of moderate or severe respiratory illness in China than were being officially reported, the tempo of the response should have been increased and threat levels raised.

By the end of January 2020, when thousands of cases had been identified outside China and the first few cases of Covid-19 had been confirmed in the UK, it should have been clear that the virus posed a serious and immediate threat. However, the limited testing capacity in the UK and a lack of adequate surveillance mechanisms, combined with a failure to assume that there was asymptomatic transmission, meant that decision-makers did not appreciate the extent to which the virus was spreading undetected.

The political system across the four nations lacked urgency and treated the emerging threat as predominantly a health issue. The obviously escalating nature of the crisis made it surprising that COBR, the UK government’s crisis coordination committee, was not chaired by the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson MP, until 2 March 2020 and that neither COBR nor the UK Cabinet met during the half-term holidays in mid-February 2020. Mr Johnson should have appreciated sooner that this was an emergency that required prime ministerial leadership to inject urgency into the response. Mr Johnson’s own failure to appreciate the urgency of the situation was due to his optimism that it would amount to nothing, his scepticism arising from earlier UK experiences of infectious diseases, and, inevitably, his attention being on other government priorities. This was compounded by the misleading assurances he received from the Cabinet Office and the Department of Health and Social Care that pandemic planning was robust, as well as the widely held view that the UK was well prepared for a pandemic. As the pandemic unfolded, the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, Matt Hancock MP, gained a reputation among senior officials and advisers at 10 Downing Street for overpromising and underdelivering.

The devolved administrations similarly failed to engage with the threat posed to their nations and were overly reliant on the UK government to lead the response. Covid-19 received no attention in Welsh Cabinet meetings before 25 February 2020. After the first case was identified in Wales on 28 February, the First Minister of Wales, Mark Drakeford MS, chose to attend St David’s Day celebrations in Brussels rather than the Welsh Cabinet meeting on 4 March 2020. In Northern Ireland and in Scotland, Covid-19 was only discussed under ‘any other business’ in meetings as late as 24 and 25 February respectively. It should have been equally apparent to the First Ministers and deputy First Ministers of the devolved administrations that, by this point, Covid-19 was the most pressing issue facing their governments.

Ministers and officials in the UK government had been given clear advice that, in the reasonable worst-case scenario, up to 80% of the population would be infected – with a very significant loss of life – but did not appreciate the increasing likelihood of this scenario materialising. At the same time, it was clear that the test and trace system was inadequate for a pandemic. The lack of urgency on the part of all four governments, and the failure to take more immediate emergency steps, are inexcusable.

The spread of the virus globally and, in particular, the escalating crisis in Italy were clear warning signs, which should have prompted urgent planning across the four nations. Instead, the governments did not take the pandemic seriously enough until it was too late. February 2020 was a lost month.

The first UK-wide lockdown (Chapters 3 and 4)

The Coronavirus: Action Plan, published on 3 March 2020, outlined the initial plan to respond to Covid-19, first by ‘containing’ its spread through testing, contact tracing and isolation of infected individuals, and then by ‘delaying’ its spread through introducing restrictions such as social distancing. Based on the strategy for pandemic influenza, the plan made a similar assumption that it would only be possible to slow, rather than prevent, the spread of the virus.

This approach was expected to lead to a degree of population immunity (otherwise known as ‘herd immunity’), where the spread of the virus through the population reduced its vulnerability to further infections. Despite a lack of clarity in media appearances, the UK government’s strategy was not to encourage the spread of the virus with the aim of achieving population immunity sooner – rather, population immunity was seen as the eventual outcome of an inevitable and widespread wave of infections.

At this stage, the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) was advising the UK government that restrictions should not be introduced until the spread of the virus was nearer its peak. This was driven partly by concerns about the negative social and economic consequences of introducing restrictions and wanting to minimise the amount of time such restrictions were in place, but also by concerns expressed by Professor (later Sir) Christopher Whitty (Chief Medical Officer for England) and Professor Sir Patrick Vallance (later Lord Vallance of Balham), Government Chief Scientific Adviser, that the public would not maintain compliance with restrictions over a long period. This concept of ‘behavioural fatigue’ had no grounding in behavioural science and proved damaging, given the imperative to act more decisively and sooner.

It is clear that the Coronavirus: Action Plan was already out of date by the time it was published. Containment had failed, as belatedly recognised by the UK government. Although there were only 39 official cases of Covid-19 in the UK by this point, the known lack of capacity for testing meant that this was clearly a significant underestimate. As the country moved to the ‘delay’ stage, from 13 March 2020, anyone with coronavirus symptoms was advised to self-isolate at home for at least seven days. However, this first restriction was too little, too late.

The lack of testing capacity had, by this point, resulted in the stopping of community testing. This meant that the UK government and devolved administrations had no real understanding of the spread of the virus in the community. Some scientists – and some civil servants and advisers within the UK government – were increasingly alarmed by the lack of urgency and the failure to act more robustly. It became clear that any opportunity to get on top of Covid-19 had been lost.

Friday 13 March 2020 was a watershed moment in the UK’s response. SAGE had concluded that the number of cases was several times higher than its previous estimates and that there were potentially thousands of cases occurring each day. The pandemic was moving faster than previously anticipated, and modelling indicated that the capacity of the NHS would be overwhelmed by the scale of infection, even if self-isolation and social distancing measures were introduced. If NHS capacity were to become overwhelmed, then far higher numbers of people would die from being unable to access medical treatment, both for Covid-19 and for other medical conditions. The plan to wait to implement restrictions until nearer the peak of the virus was no longer sustainable.

Over the next few days, decision-makers concluded that stringent measures were needed to reverse the growth of the virus. The focus remained on a package of advisory measures including self-isolation, household quarantine and social distancing. The advisory measures came into effect from 16 March 2020 and became increasingly stringent in the subsequent days, with the closure of schools and hospitality businesses from 20 March.

By 23 March 2020, SAGE estimated that the number of cases was doubling every three to four days and intensive care units in London were on track to reach capacity within ten days. Almost 300 people had died, with more than 100 of those deaths occurring in the previous two days. The situation was rapidly escalating and it was not clear that the advisory measures in place would be sufficient to prevent the NHS from being overwhelmed. A mandatory lockdown had become unavoidable.

The measures announced on Monday 16 March 2020, and strengthened through the week with the closure of schools and hospitality, should have been implemented much sooner. Had more stringent restrictions, short of a ‘stay at home’ lockdown, been introduced earlier than 16 March – when the number of Covid-19 cases was lower – the mandatory lockdown that was imposed might have been shorter or conceivably might not have been necessary at all. At the very least, there would have been time to establish what effect the restrictions had on levels of incidence and whether there was a sustained reduction in social contact. However, with measures not introduced sooner, a mandatory lockdown was the only viable option left.

The Inquiry recognises that the lockdown decision was as difficult a decision as any UK government or devolved administration has ever had to make. However, the Inquiry accepts the consensus of the evidence before it that the mandatory lockdown should have been imposed one week earlier. Had a mandatory lockdown been imposed on or immediately after 16 March 2020, modelling has established that the number of deaths in England in the first wave up until 1 July 2020 would have been reduced by 48% – equating to approximately 23,000 fewer deaths.

However, the Inquiry rejects the criticism that the four governments were wrong, in principle, to impose a lockdown. In any event, the UK government and devolved administrations had received clear and compelling advice by this time that the exponential growth in transmission would, in the absence of a mandatory lockdown, likely lead to loss of life on a scale that was unconscionable and unacceptable. No government, acting in accordance with its overarching duty to preserve life, could ignore such advice or tolerate the number of deaths envisaged. The governments acted rationally in taking the ultimate step, a mandatory lockdown, in the genuine and reasonable belief that it was required. Nevertheless, it was only through their own acts and omissions that the four governments had made such a lockdown inevitable.

Exiting the first lockdown (Chapter 5)

Upon entering the first lockdown, neither the UK government nor the devolved administrations had a strategy for when or how they would exit the lockdown. These considerations should have been at the forefront of decision-makers’ minds from the moment imposing a lockdown was contemplated. Up until this stage, the four governments had acted in unison, with the same measures applying across the whole of the UK, but they each devised their own approaches to ending the lockdown.

The easing of the majority of restrictions in England took place on 4 July 2020, despite Mr Johnson being informed by scientific advisers that this was an inherently high-risk approach as it would create an environment where infections could grow more quickly and overwhelm the ability of test and trace systems to control further outbreaks. A more cautious approach should have been taken by the UK government. Mr Johnson acknowledged that a second lockdown would be a disaster, but the approach to releasing restrictions increased the risk of this being necessary.

In contrast, the governments of Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland adopted a more gradual approach to the relaxation of restrictions throughout the summer of 2020. This more cautious approach was taken in the context of different epidemiological circumstances, but created a greater prospect of further lockdowns not being necessary or, if they were, of them not being necessary for so long. However, as there was nothing to prevent people resident in England from travelling across the internal borders of the UK, the approach adopted by the UK government risked undermining the effectiveness of the more cautious responses of the devolved administrations.

Nonetheless, in each of the four governments, insufficient attention was given to the prospect of a second wave of the virus, with only limited contingency planning in place for reintroducing restrictions if a second wave emerged.

The second wave (Chapters 6 and 7)

In the autumn of 2020, infection rates varied significantly across the UK, leading to more significant divergence in approach as all four governments tried to manage the increasing case rates at a local level. The UK government, Welsh Government and Northern Ireland Executive had all failed to learn from the experiences of the first lockdown. Local restrictions were introduced too late, were not in place for long enough or were too weak to control the spread of the virus.

Ministers are required to weigh up all competing factors in their decision-making and do not always need to follow scientific advice. However, the reasons for rejecting scientific advice – and the implications of doing so – must be clearly understood.

Throughout September and October 2020, Mr Johnson repeatedly changed his mind on whether to introduce tougher restrictions and failed to make timely decisions. For those restrictions that were introduced, such as the ‘rule of six’, SAGE had warned that they were unlikely to be effective, but Mr Johnson continued to reject SAGE’s advice to implement a ‘circuit breaker’ lockdown. The weakness of the restrictions used and Mr Johnson’s oscillation enabled the virus to continue spreading at pace, and ultimately resulted in a four-week lockdown from 5 November 2020.

Mr Johnson should have ordered the imposition of a circuit breaker lockdown in late September or early October 2020. Had a circuit breaker been utilised at that time, the second lockdown in England could have been reduced in length and severity – and might conceivably have been avoided altogether. In the event – with the opportunity to regain control having been lost – the second lockdown should have been imposed more quickly. Unlike the circuit breaker or ‘firebreak’ restrictions in Wales and the circuit breaker restrictions in Northern Ireland, the second England-wide lockdown was not timed to coincide with the school half-term holidays. Schools did, however, remain open.

The Welsh Government’s approach of targeted local restrictions was ultimately unsuccessful and led to the imposition of the firebreak. Despite receiving clear advice on 5 October 2020 that the reproduction number (the average number of people that one person with a disease infects) was above 1 and that further restrictions were needed to avoid hospital capacity being exceeded, modelling of the proposed firebreak was not sought until 11 October and the firebreak was not implemented until 23 October. From August to December 2020, Wales had the highest age-standardised mortality rate of the four nations. It is likely that this was the result of a combination of failed local restrictions, imposing the firebreak too late and the decision to relax measures more quickly than scientists advised.

Notwithstanding the imposition of circuit breaker restrictions, the decision-making in Northern Ireland was chaotic. Despite having been advised that a six-week intervention was required, the Northern Ireland Executive Committee opted for a four-week circuit breaker, which commenced on 16 October 2020. This ultimately proved inadequate. In the weeks that followed, Executive Committee meetings were deeply divided along political lines and beset by leaks, leading to an incoherent approach in which the circuit breaker restrictions were extended for one week, then lapsed for one week, before being reintroduced for two further weeks – with the one-week lapse in restrictions correlating with a 25% increase in cases.

The number of cases in Scotland in the autumn of 2020 did not reach the peaks experienced in the rest of the UK. By swiftly using stringent, locally targeted measures to deal with outbreaks, case numbers grew much more gradually and the need for a nationwide lockdown in the autumn was avoided.

Although it was not formally identified until December 2020, the more transmissible Alpha variant emerged in Kent during the autumn and drove a rapid rise in cases. The emergence of a more transmissible variant was entirely foreseeable, but all four governments failed to take decisive action in response. Rather than recognising the threat early on and introducing measures to control the virus, the governments continued to press on with plans for relaxing measures over Christmas while cases grew rapidly, only to change course on 19 December when levels of infection became critical. The mistakes of February and March 2020 were repeated – the failure to take sufficiently decisive and robust action in response had created a situation in which a return to lockdown restrictions had once again become unavoidable.

The vaccination rollout and Delta and Omicron variants (Chapters 7 and 8)

In December 2020, the UK was the first country in the world to approve a vaccine and commence a vaccination programme for Covid-19. On 2 December, temporary authorisation was granted by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency for the Pfizer/ BioNTech vaccine and the vaccine rollout commenced on 8 December. Authorisation for the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine swiftly followed on 30 December and the Moderna vaccine on 8 January 2021. This was a remarkable achievement and a decisive turning point in the pandemic.

This development enabled the four governments to take a different approach in their plans to exit their respective lockdowns, balancing the scale of infection against the additional protection from serious illness now being offered by vaccines. Plans were led by data rather than fixed dates and when the Delta variant emerged in March 2021, all four governments sensibly heeded the scientific advice to delay the planned relaxation of restrictions to allow time for the vaccine rollout to progress further. In this respect, the four governments had learned from the experience of earlier lockdowns.

Although the Omicron variant that emerged in the winter of 2021 was a less severe variant, it was much more transmissible and an estimated 5 million people in the UK were infected at the peak of the Omicron wave. Despite the enhanced protection offered by the vaccine rollout, the sheer volume of cases still led to more than 30,000 people dying with Covid-19 in the UK between November 2021 and June 2022. By the time the Omicron variant was identified, all adults had been offered two doses of the vaccine and the programme of booster doses was sensibly accelerated to offer further protection against serious illness and hospitalisation.

The approach of all four governments in the second half of 2021 carried with it an element of risk. The potential for a variant that escaped the immunity conferred by prior infection or by vaccination had been repeatedly identified as the biggest strategic risk. The sheer number of infections demonstrates that, if the vaccines had been less effective or the Omicron variant as severe as previous variants in terms of morbidity and mortality, the consequences would have been disastrous.

Key themes

Scientific and technical advice (Chapter 9)

SAGE provided high-quality scientific advice at extreme pace throughout the pandemic, but some aspects of its operation were strained by the breadth and duration of the response. There was no systematic process in place to ensure that it provided sufficient breadth of scientific expertise: participants were recruited through existing networks and professional connections, relying on people who were able to free up time from their normal jobs. Initially, there was also no clear process for the devolved administrations to gain access to SAGE discussions and advice. As the pandemic progressed, the devolved administrations used their own existing advisory scientific committees or set them up. These fed information into SAGE while applying their advice to their own local circumstances.

The effectiveness of SAGE’s advice was also constrained by the limited information provided by the UK government on its overall objectives when advice was commissioned, which made it harder for SAGE to place its advice in the right context. This lack of clearly stated objectives contributed to the conservatism of SAGE’s advice in early 2020, with participants not believing that lockdowns would be a palatable policy response and, therefore, not modelling its implications until mid-March 2020.

More significant concerns were raised about the quality of economic modelling during the pandemic. Although structures for providing economic advice were set up in Wales and Scotland, there was little evidence in each of the four nations of substantive economic modelling and analysis being provided to decision-makers. This inevitably hampered the ability of decision-makers to assess and balance relative harms.

The process for providing advice on the economic and social implications of decisions was also much more opaque than that for scientific advice. The lack of transparency of this economic and social advice, together with the repeated use of ‘following the science’ and similar phrases in communications to the public, gave a misleading impression that decisions were being taken solely on the basis of advice from SAGE. This impression may have contributed to the wholly unacceptable hostility, threats and abuse to which some experts were subject. The Inquiry strongly condemns such behaviour.

Vulnerabilities and inequalities (Chapter 10)

Although the pandemic affected everyone in the UK, the impact was not shared equally. Older people, disabled people and some ethnic minority groups faced a higher risk of dying from Covid-19. For example, when taking into account age, people from a Black African and Black Caribbean background had the highest rates of mortality during the first wave of the pandemic. From the second wave onwards, the highest mortality rates were among people of an Asian or Asian British background. The increased risk of harm was also strongly influenced by socio-economic factors, with people living in overcrowded housing or working in low-paid employment at higher risk. This often overlapped with other factors such as ethnicity.

Vulnerable groups were also affected by the restrictions introduced to control the virus. The vast majority of children were not at risk of serious direct harm from Covid-19, but suffered greatly from the closure of schools and requirement to stay at home, and the consequent loss of interaction with friends and family and limited access to play. Children were not always prioritised. No government in the UK was adequately prepared for the sudden and enormous task of educating most children in their homes and failed sufficiently to consider the consequences of school closures for children’s education and physical and mental health. Module 8 is examining these issues in more detail.

Despite this harm being foreseeable, the impact on vulnerable groups had not been adequately considered in pandemic planning, and the existing mechanisms for assessing the impact of decisions were largely applied retrospectively. Decision-makers consequently had little understanding of the impact of restrictions on vulnerable groups.

Government decision-making (Chapter 11)

COBR is designed to deal with acute emergencies and proved inadequate for responding to a prolonged pandemic. While the COBR mechanism is appropriate for assessing the initial UK-wide response to an emergency, a clearer plan for how each government will make key decisions in a prolonged emergency is needed.

The UK Cabinet was largely sidelined in decision-making, albeit that as the pandemic progressed the coordination of advice and decision-making improved and became more formalised through the Covid-19 Strategy Committee (Covid-S) and Covid-19 Operations Committee (Covid-O) and the supporting Covid-19 Taskforce. Mr Johnson’s hospitalisation in April 2020 also exposed the lack of formal arrangements for covering the absence of a Prime Minister.

Decision-making authority in the Scottish Government rested with a small group of ministers throughout the pandemic. Although the First Minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon MSP, was a serious and diligent leader who took responsibility for decisions, that also meant that ministers and advisers were often excluded from decision-making. The use of the informal Gold Command meeting structure diminished the role of the Scottish Cabinet, which frequently became a decision-ratifying body and not the ultimate decision-making body.

By contrast, the Welsh Cabinet was fully engaged throughout the pandemic, with decisions mostly being made through consensus. Mr Drakeford was recognised by his ministers as a careful and considered leader. He maintained positive relationships throughout the response.

The power-sharing arrangements in Northern Ireland are designed to ensure that each department has a significant degree of operational independence and individual ministers are afforded significant autonomy. This weakened the ability of the Northern Ireland Executive to coordinate the pandemic response and there was no one sufficiently empowered to hold departments to account. The Department of Health (Northern Ireland), which was the lead government department with responsibility for the response at the outset of the pandemic, largely operated in a silo – especially in the early stages of the response. The Northern Ireland Executive had only recently re-formed in January 2020, following a three-year period during which power-sharing was suspended, and it is unclear how decisions usually subject to ministerial approval would have been made in Northern Ireland had power-sharing still been suspended when lockdown decisions were taken.

The distinct power-sharing arrangements in Northern Ireland offered the opportunity to demonstrate that decisions were being made by all parties collectively for the greater good. Instead, however, on multiple occasions decision-making was marred by political disputes between Democratic Unionist Party and Sinn Féin ministers. The attendance of the deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland, Michelle O’Neill MLA, at the funeral of Bobby Storey in June 2020, and her initial refusal to apologise for this, contributed to tensions in the Northern Ireland Executive Committee. The four-day Executive Committee meeting from 9 to 12 November 2020 represented a low point in Northern Ireland politics during the pandemic. The confidentiality of discussions was undermined by leaks and there was inappropriate instigation of cross-community votes to make political points by the First Minister of Northern Ireland, Arlene Foster MLA (later Baroness Foster of Aghadrumsee).

The pandemic response also exposed wider cultural issues. The very least the public should be entitled to expect is that those making the rules will abide by them. Instances where ministers and advisers appeared to break Covid-19 rules caused huge distress to the public. This was especially the case for people who had endured huge personal costs to stick to the rules, with many bereaved people unable to be with their loved ones when they died. Instances where rule-breaking was not swiftly addressed also undermined public confidence and increased the risk of people not complying with the rules designed to protect them.

Decision-making was particularly affected by cultural problems in the UK government and Northern Ireland Executive. There was a toxic and chaotic culture at the centre of the UK government during the pandemic, with the Inquiry hearing evidence about the destabilising behaviour of a number of individuals – including Dominic Cummings, an adviser to the Prime Minister. By failing to tackle this chaotic culture – and, at times, actively encouraging it – Mr Johnson reinforced a culture in which the loudest voices prevailed and the views of other colleagues, particularly women, often went ignored, to the detriment of good decision-making.

Public health communications (Chapter 12)

Communication with the public is a critical aspect of a pandemic response, since controlling the virus is dependent on members of the public understanding the risk they face and acting accordingly. The ‘Stay Home’ communications campaign was effective at maximising compliance with the first lockdown, at a time when this was the understandable priority. However, the simplicity of the message meant that the intended nuances in the regulations were poorly understood, with the focus on ‘protecting the NHS’ potentially discouraging people from seeking medical treatment for non-Covid-19 conditions or from seeking help when they needed it. The balance between simplicity and detail became increasingly difficult to strike as the regulations and guidance became more complex. The introduction of localised restrictions made it difficult for members of the public to understand what rules applied to them in different places and situations, and their confusion was compounded by variations in rules across the four nations.

In focusing on how to get messages across to the whole population, the needs of vulnerable groups were sometimes lost. In particular, the UK government and Northern Ireland Executive initially failed to provide British Sign Language interpretation for press conferences or to provide key guidance in alternative formats. These are not secondary considerations. Everyone should be able to understand the action their government is asking them to take, and improvements made later in the pandemic serve to highlight the difference that proper and timely consideration of accessibility issues can make.

Legislation and enforcement (Chapter 13)

The legal response to the pandemic laid bare the limits of the UK’s legislative framework and the practical consequences of devolution. Faced with a public health crisis, the UK government relied on older public health legislation and bespoke emergency laws, rather than the Civil Contingencies Act 2004. While this enabled rapid action, it came at the cost of fragmented decision-making, reduced parliamentary scrutiny and caused public confusion.

Ministers relied on secondary legislation to implement many of the most far-reaching restrictions in modern UK history, with little or no parliamentary oversight. Across all four nations, ministers routinely used a procedure allowing laws to come into effect before they had been approved by the legislatures. While this approach was understandable in the earliest days of the pandemic, the approach continued throughout the pandemic, even when there was ample time for parliamentary scrutiny. This weakened democratic safeguards – the use of emergency regulations must be subject to greater scrutiny in future emergencies.

Frequent, complex changes to the law fuelled confusion, misunderstanding and – at times – incorrect enforcement. Police were asked to enforce unclear, shifting regulations, often issued at the last minute with little guidance. Fixed penalty notices were issued inconsistently across the UK. In England and Wales, some individuals faced £10,000 fines; in Scotland, most fines were just £60. Disproportionate impacts on certain groups were evident, especially in England, Scotland and Wales. In some cases, enforcement was practically impossible or legally uncertain – as seen in Northern Ireland during the controversy over the size of crowds at the funeral of Bobby Storey.

Time and again, public messaging failed to reflect the actual laws in place. Ministers made statements suggesting legal obligations where none existed, or vice versa. The public – and even the police – struggled to distinguish between government advice and binding legal restrictions, and there was no single, easily accessible source that clearly laid out the rules applying in each area. The resulting confusion undermined trust and compliance, particularly as legal rules diverged across the UK.

Intergovernmental working (Chapter 14)

A lack of trust between the Prime Minister and First Ministers of the devolved nations coloured the approach to involving the devolved administrations in UK government decision-making throughout the pandemic. Although the devolved administrations were invited to COBR meetings, they perceived that the decisions had already been effectively made beforehand by the UK government. COBR meetings were largely discontinued after May 2020 and intergovernmental discussions were thereafter led by the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the Cabinet Office – Michael Gove MP (later Lord Gove). The devolved administrations had a positive view of Mr Gove and felt that he was genuine in his efforts to understand their perspectives, but ultimately these meetings were limited in what they could practically achieve without Mr Johnson in attendance. Clearer structures for intergovernmental relations during an emergency, led collectively by the Prime Minister, First Ministers and deputy First Ministers, are necessary to facilitate better informed decision-making across the four nations.

Devolution has been a feature of the UK’s constitutional arrangements for over 25 years and the public is used to the devolved administrations taking different decisions from the UK government. An effective, four-nations response to a pandemic should be capable of accommodating differences in response between the nations, and it is incumbent on politicians to work collectively in the public interest in any future emergency.

Key lessons for future emergencies

In Chapter 15, in Volume II, the Inquiry presents the key lessons that should inform the response in a future pandemic. Ten lessons have been identified across five themes and these should be considered in the development of future pandemic preparedness strategies (see the Inquiry’s Module 1 Report, Recommendation 4).

Multiple scenario planning

Firstly, planning both before and during an emergency must anticipate multiple scenarios and consider the short term and long term in parallel. While no plan will ever be 100% comprehensive, the more potential scenarios that are considered in advance, the better placed decision-makers will be to react quickly and decisively.

Better strategy

Secondly, there must be an unambiguous strategy with clear objectives and a framework to guide how decisions are considered and support faster decision-making. The potential impact of those decisions should be understood in advance of them being implemented.

Acting quickly and decisively

Thirdly, when faced with a virus with the potential for exponential growth, interventions must be imposed earlier and ‘harder’ than might be considered ideal. Even where the available evidence is sub-optimal, decisions still need to be made – putting off decisions until later is in itself a decision not to intervene.

Constructive working

Fourthly, leaders must work constructively within their own governments and across the four nations. Political differences should not be a consideration at a time of national emergency. Leaders should accept responsibility for their decisions and explain clearly to the public if and when they change their mind.

The importance of data

Finally, as part of pandemic preparedness, governments must understand what data they are likely to need during a pandemic and identify how these will be collected. The limitations of data should be understood and clearly explained to decision-makers, and consideration should be given to how front-line experiences can sit alongside quantitative data.

Specific recommendations

Across this Report, the Inquiry also makes a series of recommendations aimed at improving the end-to-end decision-making process during emergencies across the four nations of the UK. Although each recommendation is important in its own right, all the recommendations must be implemented in concert – both with each other and with the recommendations from the Inquiry’s Module 1 Report – to produce the changes that the Inquiry judges to be necessary. In summary, the Inquiry recommends:

- Broadening participation in SAGE: Open recruitment of potential experts and representation of the devolved administrations would ensure that advice to decision-makers draws on a wide range of expertise. The Inquiry also recommends extending the principles of transparency of scientific advice to other forms of technical advice provided to governments, so that the public can understand the range of factors beyond scientific advice that influence decision-making during an emergency.

- Improving the routine consideration of the impact that decisions might have on those most at risk in an emergency: This includes extending to England and Northern Ireland the implementation of the socio-economic duty within the Equality Act 2010 and the use of child rights impact assessments. These changes should aim to identify, during the planning phase, any risks to which vulnerable groups are likely to be exposed during a future pandemic and to ensure that those assumptions are revisited at the outset of an emergency, that the assumptions remain valid and that adequate mitigations are in place.

- Reforming and clarifying the structures for decision-making during emergencies within each nation: Clear arrangements for synthesising advice from across governments and presenting it to decision-makers should be in place from the outset of any future pandemic. Specific recommendations are made in relation to the arrangements in Northern Ireland to avoid a potential vacuum of decision-making powers, should an emergency occur during a period where power-sharing arrangements are suspended.

- Ensuring that decisions and their implications are clearly communicated to the public: The laws and guidance in place should be easily understood, including by having clear plans for making key messages available in accessible formats such as British Sign Language.

- Enabling greater parliamentary scrutiny of the use of emergency powers through safeguards such as ‘sunset clauses’ and regular reporting on the use of powers: The role of the Civil Contingencies Act 2004 should also be re-examined to identify if, when and how it could be used in future emergencies – particularly during the initial phase. Communication of the regulations to the public should also be improved through the creation of a central repository of regulations and guidance.

- Establishing structures to improve the communication between the four nations during an emergency: These structures should aim to minimise the risk of confusion caused by similar, but different, rules being implemented in each nation, seeking alignment of approaches where desirable and providing a clear rationale for differences in approach where they are necessary.

A full list of the Inquiry’s recommendations for Modules 2, 2A, 2B and 2C is included in Appendix 3, in Volume II, to this Report.

Chapter 1: The context for pandemic decision-making – key structures and concepts

Introduction

| 1.1. | This chapter provides the context for the decisions that were taken during the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic – namely, the complex devolutional structures and the key scientific concepts. |

Key structures

Devolution in the UK

| 1.2. | The UK has a complex structure of government. The Prime Minister is the leader of the UK government and is ultimately responsible for all policy it implements and decisions it takes. The Prime Minister is supported by the UK Cabinet, which is made up of the senior members of government. Government departments and their agencies are responsible for putting government policy into practice. While some departments (such as the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and the Ministry of Defence) cover the whole of the UK, others do not. This is because some aspects of government are devolved to the Scottish Government, the Welsh Government and the Northern Ireland Executive (also referred to in this Report as the Executive Committee). The UK Parliament typically does not legislate on devolved matters without the consent of the relevant devolved legislatures: the Scottish Parliament, the Welsh Parliament and the Northern Ireland Assembly.1 |

| 1.3. | The devolved administrations are responsible for many domestic policy issues and their legislatures have law-making powers for those areas. For example, the Scottish Government, the Welsh Government and the Northern Ireland Executive are responsible for education, culture, the environment and transport in their respective nations. Critically for this Inquiry, they are also responsible for policy and laws in relation to health.2 |

| 1.4. | In the UK, powers that are not specifically reserved to the UK Parliament and UK government are devolved as follows:

Professor Ailsa Henderson, expert witness on devolution and the UK’s response to Covid-19, told the Inquiry that the differing degrees of autonomy among the devolved legislatures stemmed from their distinct origins, varying public appetite for devolution and the ad hoc, reactive changes to the devolution settlements over time.3 |

| 1.5. | The arrangements for the governance of Northern Ireland are distinct because they bring together politicians of different parties who are in opposition to each other (in terms of their designation as nationalist or unionist), along with politicians who are not aligned in this way. Together, they form an Executive Committee. This is a form of coalition government – but it is a multi-party, ‘coerced’ coalition.4 Because of the way power is shared among the political parties, there is no unified government of the day. Each Executive Department operates with significant autonomy, and individual ministers have authority to determine policy and operations within their departments without needing to maintain a collective Cabinet position. These power-sharing arrangements are not merely a framework for devolved governance but are fundamental to sustaining peace in Northern Ireland. They hold the highest constitutional significance, stemming from the Belfast Agreement of 1998 (also known as the Good Friday Agreement) and endorsed through referendums. This Inquiry does not seek to question or critique these arrangements, their structure or their rationale. |

Local services

| 1.6. | Local services are the responsibility of local councils and local authorities, as well as a number of directly elected regional mayors in England who chair combined authorities (ie groups of local councils) with specified functions and budgets. As set out in the Inquiry’s Module 1 Report, this includes regional and local activities related to civil emergencies such as pandemics.5 |

Understanding the implications for a public health emergency

| 1.7. | In a public health emergency, relevant powers span both reserved and devolved areas. For example, emergency powers, air transport and immigration are reserved to the UK government, while policing and justice are reserved in Wales but devolved in Northern Ireland and Scotland.6Key public services in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland affected by the pandemic – in particular, public health services and education – are the responsibility of the devolved administrations. |

| 1.8. | However, some devolved policy areas relevant to public health emergencies (such as health) may overlap with reserved policy areas (such as UK border control). Professor Daniel Wincott (expert witness on Welsh Government core political and administrative decision-making) referred to this overlap as the “jagged edges of devolution”,7 while Professor Paul Cairney (expert witness on Scottish Government core decision-making and political governance) noted that the boundaries between reserved and devolved responsibilities are “blurry” and “overlaps are inevitable when problems transcend individual policy sectors”.8 |

| 1.9. | In addition to this overlap, the legal powers to deal with the spread of infection are set out in different pieces of legislation for the four nations of the UK. The decision to use pre-existing public health legislation and the bespoke Coronavirus Act 2020, which was passed with the consent of the devolved legislatures – rather than the UK-wide Civil Contingencies Act 2004 – meant the response to Covid-19 followed devolved responsibilities rather than being managed more centrally.9As considered in more detail in Chapter 13: Legislation and enforcement, in Volume II, this had advantages and disadvantages. However, the pandemic necessitated shared responsibility between the UK government and the devolved administrations. |

| 1.10. | The UK government relied on a range of decision-making structures and bodies to address the crisis, including:

|

| 1.11. | In parallel, each devolved administration established its own mechanisms to manage health and emergency responses, reflecting the devolved nature of public health responsibilities. This was done as follows:

|

| 1.12. | Each of the devolved administrations has a Chief Medical Officer. The Scottish and Welsh governments also each have a Chief Scientific Adviser. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the Northern Ireland Executive did not have a cross-government adviser but had two departmental Chief Scientific Advisers. They worked with Professor (later Sir) Christopher Whitty (Chief Medical Officer for England from October 2019) and Professor Sir Patrick Vallance (later Lord Vallance of Balham), Government Chief Scientific Adviser from April 2018 to March 2023, to provide coordinated advice to government departments in all four nations. |

| 1.13. | There are a number of expert scientific advisory groups at UK level to advise the Chief Medical Officers for the four nations, health authorities and the devolved administrations directly. During the Covid-19 pandemic, these included the following:

|

| 1.14. | Although effective coordination between the UK government and devolved administrations was essential, established mechanisms for intergovernmental relations, such as the Joint Ministerial Committee – a set of committees that comprises ministers from the UK government and devolved administrations – were not used. Instead, at the outset of the Covid-19 pandemic, intergovernmental coordination was intended to function through COBR meetings and regular ministerial discussions. Ad hoc mechanisms were also introduced, including regular meetings chaired by Michael Gove MP (later Lord Gove), Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster from July 2019 to September 2021 and Minister for the Cabinet Office from February 2020 to September 2021, with the First Ministers of Scotland and Wales, as well as both the First Minister and deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland. |

| 1.15. | The pandemic therefore revealed both the strengths and challenges of the UK’s devolved system. While devolution enabled tailored responses to local circumstances, it also exposed the limitations of ad hoc coordination and the lack of institutionalised mechanisms for intergovernmental cooperation during a national crisis. Divergent approaches, overlapping responsibilities and inconsistencies in communication highlighted the need for clearer frameworks to balance flexibility with unity. Future public health emergencies will require strengthened intergovernmental structures to ensure both effective collaboration and the ability to address regional needs. |

Key scientific concepts

| 1.16. | Initial information about new viruses is always limited. Covid-19 was initially identified as pneumonia, but within a few days the World Health Organization announced that the cause of an outbreak in Wuhan in the Hubei province of China had been identified as a novel or new coronavirus.10 As summarised in the Inquiry’s Module 1 Report, coronaviruses are a large family of respiratory viruses.11 They cause a diverse range of illnesses, from the common cold to life-threatening conditions such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and the highly deadly Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). Some coronaviruses transmit easily from person to person, while others do not.12 |

| 1.17. | In order to assess the threat posed by any new and rapidly growing epidemic, it is vital to understand as quickly as possible some key aspects of how the virus is transmitted between people and how severe the illness it causes can be.13 |

Understanding transmissibility

| 1.18. | In order to assess the risk posed by an emerging virus, it is essential to know how contagious it is (ie whether and how easily it is transmitted between people). |

| 1.19. | Evidence of person-to-person transmission is “the critical tell-tale sign of a potential pandemic.14 Some viruses are only capable of transmitting between a small number of people who are in close contact with each other – such as in a family, care or work setting – before dying out. This is referred to as ‘limited’ person-to-person transmission. Other viruses may be able to continue spreading with ease from one person to the next within the wider community. This is known as ‘established’ or ‘self-sustaining’ person-to-person transmission. At SAGE’s first meeting to discuss the outbreak on 22 January 2020, it was not known whether sustained transmission was occurring.15 |

The speed of transmission

| 1.20. | Transmissibility is affected by:

|

| 1.21. | The transmissibility of a virus is measured by the reproduction number (ie the average number of people that one person with a particular disease infects). The reproduction number is also known variously as the ‘R number’, the ‘R value’, ‘R0’ (R zero), ‘Rt’ or just ‘R’. |

| 1.22. | References to the reproduction number in the evidence considered by the Inquiry – and references to it in this Report – are generally references to Rt. This is the average number of people that a single infected person passes the virus on to at a particular time point, taking into account current levels of immunity and the extent of social mixing.18 Whenever Rt is above 1, an epidemic is still growing. Whenever it is below 1, the epidemic is shrinking.19 It is Rt that interventions such as social distancing were intended to reduce. |

| 1.23. | Less commonly, there are references to ‘R0’, which represents the average number of people that one infected person would pass the virus to in a population with normal mixing behaviour and no prior immunity.20 R0 can be used to estimate the proportion of a population that will eventually become infected. On 28 January 2020, R0 for Covid-19 was estimated by SAGE to be between 2 and 3 during the first outbreak in Wuhan.21 If replicated in the UK, this would have translated to about 80% of the population becoming infected.22 |

| 1.24. | Rt and R0 can be used together to inform estimates of the ‘doubling time’ (ie how long it will take for the total number of cases to double). A doubling time of one week means that the number of cases will be twice the current size after one week, four times that size after two weeks and eight times that size after three weeks. Estimates of the doubling time of Covid-19 in the UK remained highly uncertain, given the lack of testing and concerns about the extent to which cases were not being identified. |

| 1.25. | The transmissibility of a virus is also informed by identifying when people become infectious and the period for which they remain infectious:

Taken together, the incubation period and duration of infectivity are important for informing the design of the response – particularly the length of self-isolation for infected individuals and their contacts.27 The upper estimates of an incubation period for Covid-19 of about 11 days, and a duration of infectivity of 14 days, informed the initial recommendation of a 14-day isolation period for contacts of people testing positive.28 |

| 1.26. | Increased testing of suspected cases is vital to understanding the true extent of transmissibility, and this was echoed in a message from the World Health Organization on 16 March 2020 imploring all countries to “test, test, test”.29 The data used to estimate growth also need to cover a sufficiently long period – ideally at least two weeks – to account for factors such as the typical delay in obtaining test results at weekends.30 |

Routes of transmission

| 1.27. | Alongside understanding how quickly a disease is spreading, it is important to understand how the disease spreads from person to person. The five main routes of transmission capable of sustaining a pandemic or major epidemic are: respiratory (eg influenza); sexual and blood-borne (eg human immunodeficiency virus); oral – from water or food (eg cholera); vector transmission from insects or arachnids (eg malaria); and touch (eg Ebola virus disease).31 Respiratory viruses can also transmit via objects or surfaces (known as fomites) that are contaminated by droplets or aerosols exhaled by someone infected, then transferred to people whose hands touch the contaminated surface and then their eyes, nose or mouth.32 |

| 1.28. | Covid-19 was understood from an early stage to transmit predominantly via respiratory routes.33 However, there was considerable uncertainty about the extent of transmission at closer range (typically one to two metres) via larger respiratory droplets and through very small airborne aerosols that can remain in the air for long periods of time and infect at greater distances. In the early stages of the pandemic, scientists thought most transmission was likely to be via droplets, with some fomite transmission and less aerosol spread.34 Initial advice from the World Health Organization in December 2019 suggested that the virus spread “mainly” through droplets or shorter-range aerosols, but by July 2020 there was a growing body of evidence supporting the importance of airborne transmission.35 Over the course of the pandemic, there was only a small amount of epidemiological evidence showing that a significant amount of Covid-19 was transmitted by fomites, and advice given by scientists shifted from a strong focus on cleaning surfaces and washing hands to a greater emphasis on ventilation.36 |

| 1.29. | It is also important to understand the extent to which an individual who does not display symptoms (someone with an ‘asymptomatic infection’) can infect others. This is known as ‘asymptomatic transmission’.37 In the absence of mass diagnostic testing, it is not possible to calculate the spread of a virus if symptoms are not detectable. If infected people do not show symptoms, it means that they will not know to self-isolate before they infect others. As explained by Professor Sir Michael McBride (Chief Medical Officer for Northern Ireland from September 2006):

“[T]here is a very different response required for planning for and responding to a pandemic which has asymptomatic transmission.”38 |

| 1.30. | With a reliable test, it is possible to measure the proportion of asymptomatic infections by testing a sample of the population. In February 2020, modellers from Imperial College London used data from repatriation flights from China to estimate that one-third of infections of Covid-19 were asymptomatic.39 |

| 1.31. | However, measuring the proportion of onward asymptomatic transmission is more complex, as people without symptoms will not generally be tested and the chain of transmission is unlikely to be identified unless they are tested by chance.40 At its meeting on 28 January 2020, SAGE noted that there was “limited evidence of asymptomatic transmission” but that early indications implied “some is occurring”.41 A Public Health England study carried out in six care homes across London during April 2020 identified that almost 40% of residents had tested positive for Covid-19, of whom nearly 45% were asymptomatic.42 It concluded that “symptom-based screening alone is not sufficient for outbreak control”.43 Mr Hancock told the Inquiry that this study formed the basis for adopting an assumption that asymptomatic transmission was occurring.44 |

| 1.32. | Understanding the extent of asymptomatic transmission is critical to the design of the response to a virus.45 The significant proportion of asymptomatic transmission during the Covid-19 pandemic, for example, increased the importance of contact tracing to monitor the spread of the virus and meant that personal protective equipment (PPE) needed to be used in a much wider range of settings. |

Understanding severity

| 1.33. | It is also critical to understand the severity of a new disease in the early stages of any pandemic to understand how many people might die as a result of infection.46 Estimates of fatality ratios are “fundamental to determining policy strategy”.47 Severity can be measured by the case fatality ratio and the infection fatality ratio. |

| 1.34. | The case fatality ratio is the proportion of those with a recognised case of infection who die from it. At its simplest, the case fatality ratio can be calculated as the total number of recognised deaths divided by the total number of recognised cases. However, this does not take into account unrecognised cases – particularly those where individuals have mild or no symptoms. If the recognition of cases improves (eg through more testing) then the case fatality ratio will often be corrected downwards, which would also reduce the overall expected death toll of the pandemic. At a meeting on 11 February 2020, SAGE reported an uncertain case fatality ratio of 2% to 3%.48 |

| 1.35. | The infection fatality ratio is the true proportion of all infected individuals, including those without symptoms, who die because of the infection. Estimates of the infection fatality ratio attempt to correct for biases in testing and errors in attribution of the cause of death. The true underlying number can decrease significantly over time due to natural immunity, vaccines and therapeutics, but can increase significantly if pressure on healthcare systems means infected people are not receiving timely or effective treatment. In a February 2020 report, Imperial College London estimated an infection fatality ratio for Covid-19 of approximately 1%.49 As Professor Neil Ferguson (Mathematical Epidemiologist at Imperial College London) explained:

“80% of the population being infected translates into approximately 500 thousand deaths in the UK.”50 However, the infection fatality ratio for Covid-19 varied significantly by age. On 4 March 2020, SAGE endorsed assumptions of a rate for people aged 19 and under of 0.01%, and for those aged 80 and over of 8.76%.51 |

Understanding potential responses to a pandemic

| 1.36. | In the early stages of the pandemic, one of the main priorities was to establish the likely impact of Covid-19 if it arrived in the UK in order to design a response. |

| 1.37. | In advance of sufficient data, a reasonable worst-case scenario was used as a tool for planning purposes to illustrate the worst manifestations of the risk that could reasonably be expected.52 It was not a prediction of what would happen, but the worst that could reasonably happen if no countermeasures were put in place. |

| 1.38. | It was agreed in January 2020 that the reasonable worst-case scenario for pandemic influenza should be used for government planning for Covid-19 until sufficient data emerged.53 As a result, plans proceeded on the basis of:

“the reasonable worst-case scenario … similar to a medium flu pandemic (with the added challenge of no vaccine)”54 Although it was not a prediction of what would happen, it was calculated that as many as 820,000 people in the UK might die.55This would, of course, shape the response. |

Strategies

| 1.39. | There are three key strategies that can be adopted in response to a pandemic (see Table 1), although the distinctions between these approaches continued to evolve during the course of the Covid-19 pandemic. |