اس ریکارڈ میں شامل کچھ کہانیوں اور موضوعات میں موت کے حوالے، موت کے قریب کے تجربات، بدسلوکی، جنسی استحصال اور حملہ، جبر، نظرانداز اور اہم جسمانی اور نفسیاتی نقصان شامل ہیں۔ یہ پڑھ کر تکلیف ہو سکتی ہے۔ اگر ایسا ہے تو، قارئین کی حوصلہ افزائی کی جاتی ہے کہ وہ ساتھیوں، دوستوں، خاندان، معاون گروپوں یا صحت کی دیکھ بھال کرنے والے پیشہ ور افراد سے جہاں ضروری ہو مدد لیں۔ UK Covid-19 انکوائری ویب سائٹ پر معاون خدمات کی فہرست فراہم کی گئی ہے۔

پیش لفظ

UK CoVID-19 انکوائری کے لیے یہ پانچواں ایوری سٹوری میٹرز ریکارڈ ہے۔ یہ بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے تجربات کی تحقیقات سے متعلق انکوائری کے ساتھ شیئر کی گئی ہزاروں کہانیوں کو اکٹھا کرتا ہے۔

وبائی مرض نے بہت سے بچوں اور نوجوانوں کی زندگیوں کو چھوا ہے۔ برطانیہ بھر میں، تجربہ ہر بچے اور نوجوان کے لیے مختلف تھا، جو ان کے تعلیمی تجربے، ان کے خاندانی تعلقات اور دوستی کو متاثر کرتا تھا۔ بہت سے لوگوں کے لیے ان کی دنیا راتوں رات الٹ گئی۔

جو کچھ ہم نے سنا ہے اس سے یہ واضح ہے کہ وبائی مرض میں بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے تجربات ان کے انفرادی حالات کی بنیاد پر کافی حد تک مختلف تھے – کچھ کے لیے وبائی مرض مثبت لایا اور دوسروں کے لیے اس نے موجودہ عدم مساوات کو مزید تیز کر دیا۔ جب کہ کچھ خاندان لاک ڈاؤن کے دوران کنکشن کے لیے وقت ڈھونڈنے اور بہتر بنانے کے قابل تھے، بہت سے لوگوں کو اہم چیلنجوں کا سامنا کرنا پڑا جیسے کہ دور دراز سے سیکھنے میں مشکلات، بروقت ذہنی صحت کی مدد تک رسائی، خصوصی تعلیمی ضروریات اور معذوری والے بچوں کے لیے معاونت اور تشخیص، بچوں کا آن لائن زیادہ وقت گزارنا اور آن لائن نقصان کا بڑھتا ہوا خطرہ۔

والدین نے مایوسی کی پرتوں کو بیان کیا کیونکہ وہ صحت کی دیکھ بھال، دماغی صحت کی معاونت اور خدمات یا خصوصی تعلیمی ضروریات اور معذوری والے بچوں کی تشخیص (SEND) تک رسائی کے لیے جدوجہد کر رہے تھے۔

اساتذہ، صحت کے پیشہ ور افراد اور کمیونٹی اور رضاکارانہ پیشہ ور افراد، جو بچوں کی زندگیوں کے بارے میں ایک منفرد اور معروضی نقطہ نظر رکھتے ہیں، سبھی نے بچوں اور نوجوانوں پر اس وبائی بیماری کے جذباتی نقصانات کے بارے میں سنجیدہ بیانات دیے ہیں، جیسے کہ پریشانی اور تعلیم اور معمول کے ساتھ دوبارہ مشغول ہونے میں مشکلات پر جارحیت۔ ہم نے آن لائن نقصان کا سامنا کرنے والے بچوں کے پریشان کن اکاؤنٹس اور کچھ معاملات میں گھروں میں بدسلوکی کے انکشافات بھی سنے ہیں۔

نوجوانوں نے اپنے دباؤ کے بارے میں بھی بات کی، خواہ وہ تنہائی میں پڑھ رہے ہوں، مالی عدم تحفظ کا سامنا کر رہے ہوں، یا نسل پرستی کا شکار ہوں۔ تاہم، ان کی کہانیاں لچک کے لمحات کو بھی ظاہر کرتی ہیں: مثال کے طور پر، کچھ نے اس وقت کو ورزش کرنے یا اپنی پڑھائی پر توجہ مرکوز کرنے کے لیے استعمال کیا۔

نوجوانوں اور والدین نے متحرک شہادتیں شیئر کیں کہ کس طرح پوسٹ وائرل حالات جیسے کاواساکی بیماری، پیڈیاٹرک انفلامیٹری ملٹی سسٹم سنڈروم (PIMS) اور لانگ کووڈ نے بہت سے بچوں اور نوجوانوں کی جسمانی اور جذباتی صحت کو نمایاں طور پر متاثر کیا ہے۔

یہ اکاؤنٹس، جو بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے قریب ترین لوگوں کے ذریعے شیئر کیے گئے ہیں، وبائی امراض کے دیرپا اثرات اور اس نے نوجوانوں کی زندگیوں کو تشکیل دینے کے بہت سے مختلف طریقوں پر روشنی ڈالی ہے۔ ان بالغوں اور نوجوانوں کی آوازوں اور کہانیوں کے ذریعے، وبائی مرض کے اثرات کو زیادہ مکمل طور پر سمجھا جائے گا اور انکوائری کے پاس شواہد کا ایک زیادہ گول مجموعہ ہوگا جس پر اس کی سفارشات کی بنیاد رکھی جائے گی۔

ہم ہر اس شخص کا تہہ دل سے شکریہ ادا کرتے ہیں جنہوں نے اپنے تجربات میں حصہ ڈالا، چاہے ویب فارم کے ذریعے، تقریبات میں یا ہدفی تحقیق کے حصے کے طور پر۔ اس ریکارڈ کی تشکیل میں آپ کے تاثرات انمول رہے ہیں اور ہم آپ کے تعاون کے لیے واقعی شکر گزار ہیں۔

اعترافات

ایوری سٹوری میٹرز کی ٹیم نیچے دی گئی تمام تنظیموں کے لیے اپنی مخلصانہ تعریف کا اظہار کرنا چاہے گی جنہوں نے اپنی کمیونٹیز کے اراکین کی آواز اور دیکھ بھال کے تجربات کو پکڑنے اور سمجھنے میں ہماری مدد کی۔ آپ کی مدد ہمارے لیے زیادہ سے زیادہ کمیونٹیز تک پہنچنے کے لیے انمول تھی۔ ایوری سٹوری میٹرز ٹیم کے لیے مواقع کا بندوبست کرنے کے لیے آپ کا شکریہ ان لوگوں کے تجربات سننے کے لیے جنہیں آپ اپنی کمیونٹیز میں ذاتی طور پر، اپنی کانفرنسوں میں، یا آن لائن کام کرتے ہیں۔

سوگوار، بچوں اور نوجوان لوگوں کی مساوات، ویلز، سکاٹ لینڈ اور شمالی آئرلینڈ کے فورمز، اور لانگ کوویڈ ایڈوائزری گروپس کے لیے، ہم اپنے کام پر آپ کی بصیرت، تعاون اور چیلنج کی واقعی قدر کرتے ہیں۔ آپ کے ان پٹ نے اس ریکارڈ کو تشکیل دینے میں ہماری مدد کی۔

|

|

جائزہ

یہ حصہ وبائی امراض کے دوران بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے تجربات کے بارے میں انکوائری کے ساتھ شیئر کی گئی کہانیوں کا ایک جائزہ پیش کرتا ہے۔ کہانیاں ان بالغوں کی طرف سے سنائی جاتی تھیں جو اس وقت بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے ساتھ رہ رہے تھے یا کام کر رہے تھے۔ وہ بچوں اور نوجوانوں پر وبائی امراض کے اثرات کے بارے میں ایک اہم نقطہ نظر لاتے ہیں۔ 18-25 سال کی عمر کے بچوں نے وبائی امراض کے دوران اپنے تجربات کے بارے میں کہانیاں بھی پیش کیں۔ ان نوجوانوں میں سے کچھ اس وقت 18 سال سے کم تھے۔ اس جائزہ میں کہانیوں کو جمع کرنے کے طریقوں کا خلاصہ اور کہانیوں کا خاکہ بھی شامل ہے۔

اس ریکارڈ کی آوازیں۔

انکوائری کے ساتھ شیئر کی گئی ہر کہانی کا تجزیہ کیا جاتا ہے اور وہ اس طرح کی ایک یا زیادہ تھیمڈ دستاویزات میں حصہ ڈالے گی۔ ان ریکارڈز کو انکوائری ثبوت کے طور پر استعمال کرتی ہے۔ اس کا مطلب ہے کہ انکوائری کے نتائج اور سفارشات کو وبائی امراض سے متاثر ہونے والوں کے تجربات سے آگاہ کیا جائے گا۔

ایسی کہانیاں جنہوں نے بچوں اور نوجوانوں پر وبائی امراض کے اثرات کو بیان کیا ہے وہ بنیادی طور پر یہاں بڑوں کی ان کی زندگیوں کے عینک کے ذریعے سنائی گئی ہیں۔ ان میں 18 سے 25 سال کی عمر کے نوجوانوں کی کہانیاں بھی شامل ہیں جو وبائی امراض کے دوران اپنے تجربات کے بارے میں ہیں، جب وہ 18 سال سے کم تھے اور یا تو تعلیم میں تھے، یا دیکھ بھال میں تھے۔ 18 سال سے کم عمر بچوں اور نوجوانوں نے اس ریکارڈ میں حصہ نہیں لیا۔ ان کہانیوں کو ایک ساتھ لایا گیا ہے اور اہم موضوعات کو اجاگر کرنے کے لیے تجزیہ کیا گیا ہے۔ اس ماڈیول سے متعلقہ کہانیوں کو دریافت کرنے کے لیے متعدد طریقے اختیار کیے گئے، بشمول:

- انکوائری میں آن لائن جمع کرائی گئی 54,055 کہانیوں کا تجزیہ کرتے ہوئے، قدرتی زبان کی پروسیسنگ کے مرکب کا استعمال کرتے ہوئے اور محققین نے جو کچھ شیئر کیا ہے اس کا جائزہ لینے اور کیٹلاگ کرنے والے۔

- محققین بالغوں کے ساتھ 429 تحقیقی انٹرویوز سے تھیمز تیار کرتے ہیں، جنہوں نے وبائی امراض کے دوران بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے ساتھ ساتھ وبائی امراض کے وقت 18 سے 25 سال کی عمر کے نوجوانوں کی دیکھ بھال کی یا ان کے ساتھ کام کیا۔ اس میں شامل ہیں:

- والدین، دیکھ بھال کرنے والے اور سرپرست

- اسکولوں میں اساتذہ اور پیشہ ور افراد

- صحت کی دیکھ بھال کے پیشہ ور افراد بشمول بات کرنے والے تھراپسٹ، صحت سے متعلق وزیٹر اور کمیونٹی پیڈیاٹرک سروسز

- دوسرے پیشہ ور افراد جو بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے ساتھ کام کرتے ہیں، جیسے سماجی کارکن، بچوں کے گھر کا عملہ، کمیونٹی سیکٹر کے کارکنان اور رضاکارانہ اور کمیونٹی گروپس میں پیشہ ور افراد

- وہ نوجوان جن کی عمریں 18-25 سال کی عمر کے وبائی دور میں تھیں اور وہ تعلیم میں تھے۔

- محققین انگلینڈ، سکاٹ لینڈ، ویلز اور شمالی آئرلینڈ کے قصبوں اور شہروں میں عوام اور کمیونٹی گروپس کے ساتھ ایوری سٹوری میٹرز سننے والے واقعات کے تھیمز تیار کر رہے ہیں۔ ان تنظیموں کے بارے میں مزید معلومات جن کے ساتھ انکوائری نے سننے کے ان واقعات کو منظم کرنے کے لیے کام کیا ہے اس ریکارڈ کے اعترافی حصے میں شامل ہے۔

انکوائری کی طرف سے کمیشن کردہ تحقیق کا ایک الگ حصہ، 'بچوں اور نوجوانوں کی آوازیں'، بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے تجربات اور خیالات کو براہ راست حاصل کرتا ہے۔ بالغوں کی طرف سے سنائی گئی کہانیاں مختلف نقطہ نظر اور بصیرت کا اضافہ کرتی ہیں۔

براہ کرم نوٹ کریں کہ یہ ایوری سٹوری میٹرز کا ریکارڈ طبی تحقیق نہیں ہے – جب کہ ہم شرکاء کی طرف سے استعمال ہونے والی زبان کی عکس بندی کر رہے ہیں، جس میں 'اضطراب'، 'ڈپریشن'، 'کھانے کی خرابی' جیسے الفاظ شامل ہیں، یہ ضروری نہیں کہ طبی تشخیص کا عکاس ہو۔

بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے بارے میں شراکت داروں کے فراہم کردہ اکاؤنٹس کو کس طرح اکٹھا کیا گیا اور تجزیہ کیا گیا اس کے بارے میں مزید تفصیل اس تعارف میں اور اس میں بیان کی گئی ہے۔ اپینڈکس. ضمیمہ میں کلیدی گروپوں، بچوں اور نوجوانوں سے متعلق مخصوص پالیسیوں اور طریقوں کا حوالہ دینے کے لیے پورے ریکارڈ میں استعمال ہونے والی اصطلاحات اور فقروں کی فہرست شامل ہے۔

یہ دستاویز مختلف تجربات کی عکاسی کرتی ہے بغیر ان کو ملانے کی کوشش کی، کیونکہ ہم تسلیم کرتے ہیں کہ ہر ایک کا تجربہ منفرد ہوتا ہے۔

ہم نے اس ریکارڈ کے لیے مختلف قسم کے مشکل تجربات سنے۔ پورے ریکارڈ میں، ہم نے یہ واضح کرنے کی کوشش کی ہے کہ آیا تجربات وبائی امراض کا نتیجہ تھے یا پہلے سے موجود چیلنجز جو اس عرصے کے دوران بڑھ گئے تھے۔ یہ ایک پیچیدہ کام تھا۔

جہاں ہم نے اقتباسات کا اشتراک کیا ہے، ہم نے اس گروپ کا خاکہ پیش کیا ہے جس نے نقطہ نظر کا اشتراک کیا ہے (مثلاً والدین یا سماجی کارکن)۔ والدین اور اسکول کے عملے کے لیے، ہم نے خاکہ بھی بنایا ہے۔ ان کے بچوں یا ان بچوں کی عمر کی حدود جن کے ساتھ وہ وبائی امراض کے آغاز میں کام کر رہے تھے۔. ہم نے برطانیہ میں اس قوم کو بھی شامل کیا ہے جس کا تعاون کرنے والا ہے (جہاں سے معلوم ہے)۔ اس کا مقصد ہر ملک میں کیا ہوا اس کا نمائندہ نقطہ نظر فراہم کرنا نہیں ہے، بلکہ CoVID-19 وبائی مرض کے برطانیہ بھر میں متنوع تجربات کو ظاہر کرنا ہے۔

کہانیوں کا خاکہ - بچوں اور نوجوانوں پر وبائی امراض کے اثرات

خاندانی تعلقات پر اثرات

ہم نے سنا ہے کہ بہت سے بچے وبائی امراض کے دوران خاندان کے ساتھ معیاری وقت اور ان کی مدد سے محروم رہے۔ دور سے کام کرنے والے کچھ والدین نے یاد کیا کہ وہ اکثر کام کے دباؤ کی وجہ سے اپنے بچوں کے ساتھ اتنا مشغول نہیں ہو پاتے تھے جتنا وہ چاہتے تھے۔ اس نے کچھ بچوں کو تنہا محسوس کیا اور کمپنی کے لیے اسکرینوں پر انحصار کیا۔ جن بچوں کے والدین الگ ہو گئے تھے انہیں والدین اور بعض اوقات بہن بھائیوں کے علاوہ طویل ادوار کا سامنا کرنا پڑتا ہے۔

والدین نے ہمیں بتایا کہ کس طرح دادا دادی کے ساتھ رابطہ بھی شدید طور پر محدود تھا، جس سے بچوں کے اپنے بڑھے ہوئے خاندان سے تعلق کے احساس پر اثر پڑتا ہے۔

| " | میرے خاندان کو ساتھ نہ رہنے کی وجہ سے بہت زیادہ نقصان پہنچا۔ خاص طور پر میرے بچے، اپنے دادا دادی کو اتنی دیر تک گلے لگانے کے قابل نہ ہونے سے

- والدین، انگلینڈ |

| " | میں جانتا ہوں کہ کووِڈ کے بہت سے متحرک حصے ہیں لیکن یہ واضح نہ کرنے سے کہ والدین اپنے بچوں کے ساتھ کس طرح بات چیت کرتے ہیں اس کا مجھ پر اور میرے خاندان پر خوفناک اثر پڑا ہے اور یہ بلا شبہ برسوں اور سالوں تک جاری رہے گا… یہ ایک آسان حل ہوتا - مینڈیٹ کہ جب بچوں تک مشترکہ رسائی کا انتظام ہو تو اسے جاری رکھا جائے گا … کوئی گرے ایریاز نہیں، کوئی ایسا علاقہ نہیں جس کو چیلنج کیا جا سکے - یہ آسان حل اسے حل کر دیتا۔ اب میں اپنے سب سے بڑے دماغی صحت کے مسائل کے ساتھ رہ گیا ہوں جس کا اپنے خاندان کے 50% کے ساتھ کوئی تعامل نہیں ہے۔

- پیarent، انگلینڈ |

لاک ڈاؤن اور گھر میں زیادہ وقت گزارنے کا مطلب یہ تھا کہ کچھ بچوں اور نوجوانوں نے اپنے والدین کی مدد کے لیے کھانا پکانے اور چھوٹے بہن بھائیوں کی دیکھ بھال جیسی نئی ذمہ داریاں سنبھال لیں۔ والدین کی ملازمت میں تبدیلی، بڑھتے ہوئے مالی دباؤ، اور ذاتی صحت کے مسائل نے کچھ بچوں کو اپنے خاندانوں میں دیکھ بھال کی ذمہ داریاں سنبھالنے پر مجبور کیا۔ والدین اور پیشہ ور افراد نے ہمیں بتایا کہ اس سے ان کی صحت اور خاندانی تعلقات متاثر ہوئے۔ پیشہ ور افراد نے بیان کیا کہ کس طرح نوجوان دیکھ بھال کرنے والوں کو ضروری امدادی خدمات کے نقصان اور ان کی نگہداشت کے فرائض سے اہم مہلت کا سامنا کرنا پڑا جو عام طور پر اسکول میں شرکت کرتے ہیں۔ نگہداشت کی اضافی ذمہ داریوں سے نمٹنے کی کوشش کرتے ہوئے اس نے انہیں الگ تھلگ محسوس کیا۔

| " | چونکہ میں باہر کام کر رہا تھا، مجھے لگتا ہے کہ چیزوں کی دیکھ بھال کے لیے سب کچھ بڑے لڑکے پر چھوڑ دیا گیا تھا۔ مجھے لگتا ہے کہ اس نے محسوس کیا کہ اسے ایسے کام کرنے پر مجبور کیا جا رہا ہے جو اسے نہیں کرنا چاہئے، جیسے کہ اصول طے کرنا اور اپنے بہن بھائیوں کو باہر نہ جانے کو بتانا۔ اس نے محسوس کیا کہ ذمہ داری اس پر عائد ہوتی ہے کہ وہ انہیں روکے رکھے۔

- 11، 13 اور 18 سال کی عمر کے بچوں کے والدین، سکاٹ لینڈ |

| " | نوجوان دیکھ بھال کرنے والے اپنا سارا وقت گھر پر گزار رہے تھے اور ان کی دیکھ بھال کرنے والوں سے کوئی مہلت نہیں مل رہی تھی۔ ہم نے کچھ واقعی افسوسناک کہانیاں سنی ہیں جہاں نوجوان صرف اس لیے مغلوب ہو گئے تھے کیونکہ ان کے پاس اپنے لیے وہ وقت نہیں تھا، اس لیے میرے خیال میں ان پر گہرا اثر پڑا تھا۔ اور پھر ظاہر ہے کہ اگر وہ والدین کی دیکھ بھال کرنے کی وجہ والدین کی ذہنی صحت کے ساتھ ہے، تو یہ کافی خوفناک بھی ہو سکتا ہے۔

- کمیونٹی سیکٹر ورکر، انگلینڈ |

والدین اور پیشہ ور افراد نے ہمیں بتایا کہ گھر میں قید رہنے سے خاندانی تنازعات اور تناؤ بڑھتا ہے۔

| " | گھر کے اندر خاندانی تعلقات کشیدہ ہو گئے کیونکہ ہم سب ایک ساتھ بہت زیادہ وقت گزار رہے تھے اور کام یا اسکول جانے کے قابل نہیں تھے۔

- والدین، انگلینڈ |

اس عرصے میں کچھ گھرانوں میں گھریلو زیادتی کے واقعات میں بھی اضافہ دیکھنے میں آیا۔ ایسے خاندانوں کے لیے جو پہلے ہی بدسلوکی کا سامنا کر رہے ہیں، لاک ڈاؤن نے ان کے تجربے کو مزید خراب کر دیا اور بچوں کے لیے فرار یا مہلت کے کسی بھی امکان کو ختم کر دیا، جو کہ بہت پریشان کن تھا۔ پیشہ ور افراد نے پریشان کن اکاؤنٹس فراہم کیے جہاں کچھ بچوں کو جنسی زیادتی کا سامنا کرنا پڑا جب وہ اپنے بدسلوکی کرنے والوں کے ساتھ گھر میں پھنس گئے۔

| " | لاک ڈاؤن کے اثرات کا مطلب یہ تھا کہ بچے اور گھریلو زیادتی کے شکار افراد کو ان کے ساتھ زیادتی کرنے والوں کے ساتھ الگ تھلگ کر دیا گیا تھا۔

- سماجی کارکن، انگلینڈ |

دیکھ بھال کرنے والے بچوں کا پیدائشی خاندانوں کے ساتھ آمنے سامنے کا رابطہ اچانک ویڈیو کالز نے لے لیا اور چھوٹے بچوں کو خاص طور پر اسکرینوں کے ذریعے جذباتی طور پر جڑنے کے لیے جدوجہد کرنا پڑی۔ بچوں کو جگہ کے تعین میں مزید خرابی کا سامنا کرنا پڑا، یعنی ان کی زندگیوں میں مزید خلل۔

| " | اس سے پہلے وہ اپنے خاندان کے ساتھ آمنے سامنے جا سکتے تھے۔ بہت سارے بچے روزانہ گزرنے پر انحصار کرتے ہیں کیونکہ وہ جانتے ہیں کہ جمعہ کو وہ اپنی ماں یا اپنے والد یا بہن بھائیوں یا دوستوں سے ملنے جا رہے تھے۔ میں کہوں گا کہ یہ جذباتی طور پر کافی مشکل تھا کیونکہ یہ ان کے لیے ایک ڈرائیور تھا۔ لہذا، ہم اس وقت FaceTime استعمال کر رہے تھے لہذا انہیں ابھی بھی کچھ رابطہ کرنا پڑا، لیکن یہ آپ کی ماں کی طرف سے کوئی گلہ نہیں ہے۔

- بچوں کے گھر کا عملہ، سکاٹ لینڈ |

تاہم، دوسرے پیشہ وروں نے ہمیں بتایا کہ ایک اقلیت نے رابطے میں توقف سے فائدہ اٹھایا کیونکہ اس سے استحکام آیا اور بچوں اور نوجوانوں کو اپنے جذبات کو بہتر طریقے سے منظم کرنے کی اجازت ملی۔

| " | ایسا لگا جیسے یہاں کے رہنے والے بچے واقعی لاک ڈاؤن میں پروان چڑھے۔ ان کی دنیایں چھوٹی ہو گئیں، ان کے معمولات زیادہ سخت تھے، یہ کافی محفوظ محسوس ہوا۔

- رہائشی نگہداشت کے اسکول کا عملہ، گلاسگو سننے کی تقریب |

ان مشکل تجربات کے دوران، کچھ خاندانوں نے پایا کہ وبائی مرض کے دوران ایک ساتھ وقت گزارنے سے ان کے تعلقات مضبوط ہوتے ہیں۔ والدین نے یاد کیا کہ وہ کس طرح اپنے بچوں کے قریب ہوئے، ایک ساتھ زیادہ معیاری وقت کا لطف اٹھایا جیسے کہ واک کرنا اور گیم کھیلنا۔

| " | میں اور میرے بچے اب ایک ساتھ اتنا وقت گزارنے کے موقع کے نتیجے میں بہت قریب ہیں، اسکرینوں سے دور، باہر خوبصورت موسم سے لطف اندوز ہوتے ہیں۔ دھوپ کی چھٹی کے ان 6 مہینوں میں بنایا گیا بانڈ کبھی ختم نہیں ہوگا۔

- والدین، انگلینڈ |

| " | میرے خیال میں خاندانوں کے اندر تعلق کا مجموعی احساس مثبت تھا کیونکہ وہاں کوئی بیرونی محرک نہیں تھا۔ کبھی کبھی کم زیادہ ہوتا ہے۔ اس نے لوگوں کو ان تعلقات کو فروغ دینے کی اجازت دی اور درحقیقت، آپ کے پاس صرف ایک دوسرے کے ساتھ رہنے کے سوا کوئی چارہ نہیں تھا اور اس نے واقعی تعلقات کو مضبوط کیا۔

- سماجی کارکن، ویلز |

سماجی تعاملات پر اثرات

معاونین نے روشنی ڈالی کہ وبائی مرض نے بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے دوستوں اور ساتھیوں کے ساتھ سماجی روابط کو کافی حد تک متاثر کیا۔ لاک ڈاؤن اور پابندیوں نے انہیں اسکول میں دوستوں یا سماجی سرگرمیوں کے ذریعے دیکھنے سے روک کر ان کی ذاتی بات چیت کو کافی حد تک کم کیا، عام طور پر انہیں مجبور کیا کہ وہ اپنی سماجی کاری کو مکمل طور پر آن لائن منتقل کریں۔ والدین اور نوجوانوں نے یاد کیا کہ کس طرح وبائی مرض نے بہت سے لوگوں کو تنہا اور الگ تھلگ محسوس کیا۔

| " | پورا خاندان ڈپریشن کا شکار ہے … میرے بچے کیونکہ وہ اپنے ساتھیوں اور وسیع تر خاندان سے الگ تھلگ تھے۔

- والدین، انگلینڈ |

| " | اس کے ساتھ آنے والی سماجی تنہائی ہر چیز کو بڑھا دیتی ہے، ہے نا؟ آپ اپنے دوستوں سے اتنی آسانی سے بات نہیں کر سکتے کہ کیا ہو رہا ہے اور ان کا اس پر کیا اثر ہے … کبھی کبھی یہ جان کر خوشی ہوتی ہے کہ آپ سب ایک ہی ڈوبتے ہوئے جہاز پر ہیں!

- نوجوان شخص، سکاٹ لینڈ |

اب بھی ذاتی طور پر اسکول جانے والے بچوں کے والدین، جیسے اہم کارکنان یا کمزور بچے، نے ذاتی طور پر کچھ سماجی رابطے کو نوٹ کیا لیکن کم بچوں کے ساتھ اور مخلوط عمر کے گروپوں میں۔ یہاں تک کہ جب اسکول مکمل طور پر دوبارہ کھل گئے، سماجی دوری اور بلبلوں جیسی پابندیاں1 بچوں کو پہلے کی طرح اکٹھے کھیلنے سے روکا، ان میں الجھن پیدا کر دی اور تنہائی میں اضافہ کیا۔

| " | وہ پرجوش تھی اور اسکول واپس جانے اور اپنے دوستوں سے ملنے کی منتظر تھی۔ لیکن چونکہ یہ تمام اقدامات اسکول واپس جانے پر لاگو کیے گئے تھے، اس لیے آپ کو اپنے دوستوں سے دو میٹر کے فاصلے پر کلاس روم میں اپنی میز پر بیٹھنا پڑتا تھا، اور آپ کو کھیل کے میدان اور اس طرح کی چیزوں پر میٹر کے فاصلے پر قطار میں لگنا پڑتا تھا۔ یہ اس کے ساتھ جذباتی طور پر الجھ گیا۔

- رضاعی والدین، انگلینڈ |

والدین اور پیشہ ور افراد نے وضاحت کی کہ بچوں کی تنہائی کی حد ان کے گھریلو حالات پر منحصر ہے۔ شراکت داروں نے مشاہدہ کیا کہ کس طرح بہن بھائیوں، بڑھے ہوئے کنبے یا ہمسایوں کے ساتھ ایک جیسی عمر کے لوگ جن کے ساتھ بات چیت کرنا ہے ان کے مقابلے میں صرف بالغوں کے ساتھ رہنے والوں کے مقابلے میں مل جلنے کے زیادہ مواقع تھے۔ وہ بچے جو حفاظت کر رہے تھے یا جن کے خاندان کے افراد طبی لحاظ سے کمزور ہیں، انہوں نے تنہائی کے گہرے احساس کا تجربہ کیا۔

| " | باقی تمام بچے جن کے بھائی اور بہنیں ہیں۔ وہ اب بھی کسی اور کے ساتھ بات چیت کر رہے ہیں، اپنے گھر میں مزے کر رہے ہیں، اور کھیل کھیلتے ہیں اور مذاق کرتے ہیں اور ڈمی لڑائی کرتے ہیں۔ وہ کام جو بہن بھائی کرتے ہیں۔ وہ گھر میں دو والدین کے ساتھ تھی جو ہر چیز سے پریشان تھے۔

- 14 سالہ بچے کے والدین، سکاٹ لینڈ |

| " | میرے چند خاندان ایسے تھے جن کے والدین دائمی بیماری یا کینسر میں مبتلا تھے یا کینسر کے علاج سے گزر رہے تھے۔ ان بچوں میں سے کچھ ایسے تھے جو مکمل طور پر الگ تھلگ تھے کیونکہ ان کے والدین کو ڈھال بنانا تھا۔ یہاں تک کہ جب پابندیوں کو ڈھال لیا گیا تو وہ سب سے الگ تھلگ تھے کیونکہ وہ موافقت کے ساتھ بھی ترقی نہیں کر سکتے تھے۔

- ہیلتھ وزیٹر، سکاٹ لینڈ |

والدین اور پیشہ ور افراد نے مسلسل اطلاع دی کہ زیادہ تر بچے اور نوجوان لاک ڈاؤن کے دوران دوستی برقرار رکھنے کے لیے آن لائن پلیٹ فارمز پر زیادہ انحصار کرتے ہیں۔ اس سے بہت سے لوگوں کو کم الگ تھلگ محسوس کرنے میں مدد ملی، لیکن تجربات عمر کے لحاظ سے مختلف ہوتے ہیں۔ تعاون کنندگان نے ہمیں بتایا کہ چھوٹے بچے آن لائن مواصلت کے لیے آلات استعمال کرنے سے واقف نہیں تھے اور ہو سکتا ہے کہ ان کے پاس ورچوئل تعاملات کے لیے ضروری مہارتیں نہ ہوں، یعنی یہ ان کے لیے نوعمروں کے مقابلے میں زیادہ مشکل تھا۔ کچھ کے لیے، آن لائن پلیٹ فارمز نے بچوں اور نوجوانوں کو ان کی فوری برادریوں سے ہٹ کر اور عالمی سطح پر نئے کنکشن بنانے کے قابل بنایا۔

| " | صبح سے لے کر رات تک، یا صبح کے اوائل تک، لوگ عملی طور پر ایک دوسرے سے جڑے رہتے تھے اور یہ نوجوانوں کے لیے ایک بہت بڑا مثبت تھا کیونکہ اس کا مطلب یہ تھا کہ ان میں سے بہت سے لوگ خود کو الگ تھلگ محسوس نہیں کرتے، اپنے دوستوں کے ساتھ گیمنگ میں اپنا وقت گزار سکتے ہیں، یا اپنے دوستوں سے بات چیت کر رہے ہیں۔

- معالج، انگلینڈ |

| " | ایک معذور شخص کے طور پر دنیا میری سیپ بن گئی، ہر کوئی آن لائن تھا، میں نے مائن کرافٹ اسکائی: چلڈرن آف دی لائٹ، پورٹل، روبلوکس اور سٹارڈیو وادی اپنے شوق گروپ کے ساتھ کھیلا، ہم دوپہر کو ایک ڈسکارڈ کال شروع کرتے اور اس وقت تک کال پر رہتے جب تک کہ ہم بہت تھک نہ جائیں۔

- نوجوان شخص، شمالی آئرلینڈ |

تاہم، زیادہ وقت آن لائن گزارنے سے دھونس اور نقصان کے خطرات میں اضافہ ہوتا ہے، خاص طور پر کمزور بچوں کے لیے۔ کچھ بچوں اور نوجوانوں نے لاک ڈاؤن کے دوران ذاتی طور پر غنڈہ گردی سے مہلت کا تجربہ کیا، لیکن دوسروں کو شدید سائبر دھونس کا سامنا کرنا پڑا۔ پیشہ ور افراد نے بار بار اس خیال کا اظہار کیا کہ آن لائن زیادہ غیر نگرانی شدہ وقت بچوں کے استحصال، گرومنگ، واضح مواد کی نمائش اور خطرناک غلط معلومات کے خطرے کو بڑھاتا ہے۔

| " | بچے اور نوجوان [آن لائن] بہت زیادہ وقت گزار رہے تھے۔ آن لائن ایک بہترین جگہ ہے، لیکن بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے لیے آن لائن بہت سی کمزوریاں ہیں۔ ہم نے سائبر دھونس اور بچوں کو آن لائن تیار ہوتے دیکھا ہے … بچے ایسی چیزوں تک رسائی حاصل کرنے کے قابل ہوتے ہیں جو ضروری طور پر ان کی عمر یا صرف ترقی کے مرحلے کے لیے مناسب نہیں ہیں۔

- سماجی کارکن، انگلینڈ |

والدین اور پیشہ ور افراد نے بتایا کہ پابندیوں میں نرمی کے بعد کس طرح کچھ بچے اسکول اور سماجی سرگرمیوں میں واپس آنے پر خوش تھے۔ اس کے برعکس، بہت سے بچوں اور نوجوانوں نے اپنی سماجی مہارتوں میں اعتماد کھونے کے بعد، ذاتی طور پر بات چیت کو اپنانے کے لیے جدوجہد کی۔ پیشہ ور افراد نے خاص طور پر مشورہ دیا کہ چھوٹے بچوں (5 سال سے کم عمر) کی سماجی نشوونما میں رکاوٹ ان کے اشتراک کرنے، مل کر کام کرنے اور دوستی قائم کرنے کی صلاحیت پر زیادہ دیرپا اثرات مرتب کرتی ہے۔ والدین اور اساتذہ نے مزید اس بات پر زور دیا کہ وبائی امراض کے دوران نئے اسکولوں یا یونیورسٹیوں میں منتقل ہونے والے نوعمروں کو بھی بعد میں نئے ساتھیوں کے ساتھ مربوط ہونا اور ان سے جڑنا مشکل محسوس ہوا۔

| " | نرسری کے بچوں میں سماجی مہارت کی کمی ہے کیونکہ یہ لاک ڈاؤن کے دوران پیدا ہوئے تھے۔ استقبال کرنے والے عمر رسیدہ بچوں میں بھی سماجی مہارتوں کی کمی ہے اور بہت سے بڑے گروپ میں پریشانی کا شکار ہیں۔ سال 1 کے بچے لاک ڈاؤن کی وجہ سے نرسری میں نہیں گئے تھے اس لیے بہت سے ہنر جو انھوں نے سیکھے ہوں گے ضرورت کے وقت انھیں دستیاب نہیں تھے۔ سال 2 کے بچے اپنی سماجی مہارتوں میں ناپختہ ہیں اور انہیں مستقبل کی تعلیم کے لیے درکار ہنر حاصل کرنے میں مدد کرنے کے لیے بہت سی مداخلتیں کی جا رہی ہیں۔

- ٹیچر، انگلینڈ |

| " | میرے بچے الگ تھلگ اور تنہا تھے۔ میرے بیٹے نے پہلے سے ہی جدوجہد کرنا شروع کر دی اور 9 سال کی عمر میں ایک نئے اسکول میں گیا – اس کے پاس بمشکل وقت تھا کہ وہ اپنے نئے دوستوں کو جان سکے جب کووڈ نے حملہ کیا۔ اس کے اسکول نے آن لائن کام یا رابطہ بالکل بھی نہیں کیا … سماجی بنانا ناممکن تھا۔ وہ اہم سال جو وہ سماجی مہارتیں سیکھ سکتا تھا، وہ گزر گئے۔

- والدین، انگلینڈ |

تعلیم اور سیکھنے پر اثرات

والدین نے ہمیں بتایا کہ وبائی امراض کے آغاز میں اسکولوں کو دور دراز کی تعلیم میں منتقل ہونے میں کیسے وقت لگا۔ کچھ اسکولوں نے ان بچوں کے لیے کاغذی وسائل فراہم کیے جو آن لائن ٹولز کے ساتھ مشغول ہونے کے لیے بہت چھوٹے تھے اور ساتھ ہی ان لوگوں کے لیے جو ضروری ٹیکنالوجی تک رسائی نہیں رکھتے تھے۔ بہت سے لوگوں کو گھر میں ٹیکنالوجی یا انٹرنیٹ تک رسائی کی کمی کی وجہ سے آن لائن سیکھنے میں مشغول ہونے کے لیے جدوجہد کرنا پڑی۔ تعاون کنندگان نے اطلاع دی کہ کچھ اسکولوں نے آلات قرض دے کر یا انٹرنیٹ تک رسائی فراہم کرکے مدد کرنے کی کوشش کی، لیکن کچھ خاندانوں کو پھر بھی یہ مشکل لگا، خاص طور پر بڑے گھرانوں میں جہاں آلات کا اشتراک کرنا پڑتا ہے۔

| " | شروع میں، میں یہ صرف اپنے فون پر کر سکتا تھا، اس لیے مجھے ایک فون پر دو اسکولی بچوں کے اسکول کے کام کی [نگرانی] کرنے کی کوشش کرنی پڑی۔

- 9 اور 12 سال کی عمر کے بچوں کے والدین، ویلز |

| " | ہر ایک کے پاس براڈ بینڈ نہیں ہے، اور میرے خیال میں یہ ظاہر ہو گیا، کہ یہ ہمیشہ اتنا قابل رسائی نہیں تھا۔ یہ صرف یہ سمجھا گیا تھا کہ بچے صرف آن لائن کود سکتے ہیں اور کچھ کر سکتے ہیں۔ لیکن یہاں کے کچھ علاقوں میں غربت بہت زیادہ ہے۔ لہذا ہر ایک کو ہر ایک کی طرح رسائی حاصل نہیں ہوسکتی ہے۔

- 2، 5 اور 14 سال کی عمر کے بچوں کے والدین، سکاٹ لینڈ |

ریموٹ سیکھنے کے ساتھ مشغولیت کافی مختلف تھی۔ مسابقتی ذمہ داریوں کی وجہ سے والدین کی مدد ہمیشہ ممکن نہیں تھی۔ والدین نے بتایا کہ بچے سیکھ رہے ہیں مادی مواد میں ان کے اعتماد کی کمی بھی اس بات کا ایک عنصر ہے کہ وہ دور دراز کی تعلیم کو کس حد تک مدد دے سکتے ہیں۔ والدین اور اساتذہ نے ہمیں بتایا کہ چھوٹے بچوں کو ذاتی طور پر بات چیت کے مقابلے میں اکثر اسکرینوں کے ذریعے رابطہ کو الجھا ہوا اور منقطع پایا جاتا ہے۔ پرانے طلباء بعض اوقات کیمرے اور مائیکروفون بند رکھ کر شرکت سے گریز کرتے تھے۔

| " | ہمارے بچے تباہ ہو گئے۔ ہر صبح انہیں ان کے اساتذہ [الیکٹرانک] ورک شیٹ بھیجتے تھے۔ میرے بچوں (خاص طور پر سب سے چھوٹے) نے کبھی بھی بغیر نگرانی کے اسکرین کا استعمال نہیں کیا تھا – اب، دونوں والدین کے ساتھ کل وقتی کام کرتے ہیں، ہم ان سے شیٹ کی پیروی کرنے، جواب بھرنے اور خود کو سکھانے کے لیے کہہ رہے تھے۔ کوئی لائیو اسباق نہیں تھے۔ کام بورنگ اور بے مقصد تھا۔ اگر وہ ایسا نہیں کر سکتے تھے، تو انہیں والدین کی مدد کے لیے آزاد ہونے کا انتظار کرنا پڑتا تھا۔

- والدین، انگلینڈ |

| " | میری بیٹی اپنا کیمرہ بند کر دیتی تھی اور بس اسے کھول دیتی تھی اور وہ بالکل مختلف کام کر رہی ہوتی تھی۔ وہ اس [اسکول کے کام] کے بارے میں تھوڑا سا نوٹس نہیں لے رہی تھی، جو قابل فہم ہے، کیونکہ یہ زیادہ دل چسپ نہیں تھا۔ انہوں نے اپنی پوری کوشش کی، لیکن واقعی یہ بے سود تھا۔

- 5 اور 8 سال کی عمر کے بچوں کے والدین، انگلینڈ |

سیخصوصی تعلیمی ضروریات اور معذوری والے بچے (بھیجیں)2 ریموٹ لرننگ کے ساتھ اضافی چیلنجوں کا سامنا کرنا پڑا کیونکہ کچھ کو سیکھنے میں مشغول ہونے کے لیے ماہر معاونت کی ضرورت ہوتی ہے جیسے کہ تدریسی معاون کی مدد۔ اس کے برعکس، شراکت داروں نے اس بات پر روشنی ڈالی کہ SEND والے کچھ بچوں کو دوسروں کے ساتھ مشغول ہونے کے سماجی دباؤ سے دور، گھر میں رہنے کا لطف آتا ہے۔

| " | تعلیمی صحت کی دیکھ بھال کے منصوبوں کے ساتھ خصوصی تعلیمی ضروریات کے طور پر درجہ بندی کرنے والے بچوں کے لیے آن لائن سیکھنا واقعی مشکل تھا، کیونکہ ان کے پاس اپنے معاون کارکن تک ذاتی طور پر رسائی نہیں تھی، جو عام طور پر نوٹ لے رہے ہوں، اسے توڑ رہے ہوں اور ان کے ساتھ کام کر رہے ہوں، لیکن آن لائن ان کے لیے ایسا کرنا بہت مشکل تھا۔

- مزید تعلیم کے استاد، انگلینڈ |

| " | میں ان بچوں کے ساتھ بھی کام کرتا ہوں جو واقعی اسکول کے ساتھ جدوجہد کرتے ہیں اور اسکول ان کے لیے محفوظ جگہ نہیں ہے۔ درحقیقت، اسکول وہ جگہ ہے جہاں وہ مختلف وجوہات کی بناء پر واقعتاً رہنا پسند نہیں کرتے۔ وہ اپنے خاندان کے ساتھ گھر میں رہنے سے لطف اندوز ہوتے تھے۔ ان میں سے کچھ گھر میں بہتر کام کرنے کے قابل تھے کیونکہ یہ ان کے لیے اسکول سے مختلف ماحول تھا۔

- سماجی کارکن، سکاٹ لینڈ |

اساتذہ، والدین اور نوجوانوں نے نوٹ کیا کہ کس طرح وبائی مرض نے اہم تعلیمی سرگرمیوں جیسے ہینڈ آن لرننگ، گروپ ورک اور اساتذہ سے براہ راست فیڈ بیک حاصل کرنے کے مواقع کو محدود کردیا۔ بچے اور نوجوان اہم عملی اور تعلیمی مہارتوں کو تیار کرنے سے محروم رہے۔ انگریزی کو ایک اضافی زبان کے طور پر رکھنے والے طلباء کے لیے، انگریزی سیکھنے میں خود کو غرق کرنے کا موقع محدود تھا۔

| " | ہر چیز ایک اسکرین پر مرکوز ہے، اور ہر چیز ایک ڈیوائس پر مرکوز ہے، جب کہ ہماری سیکھنے کے بارے میں بہت کچھ ہے … جیسے، مثال کے طور پر، ہم ایک پرنٹ میکنگ سیشن کریں گے جہاں آپ پرنٹ میکنگ اسپیس میں ہوں گے، اور یہ کام کر رہا ہو گا اور آرٹ سٹوڈیو میں گڑبڑ کرنے کے قابل ہو گا اور اس تخلیقی آزادی کے ساتھ۔

- مزید تعلیم کے استاد، انگلینڈ |

| " | آمنے سامنے سیمینار کرنا یقینی طور پر زیادہ فائدہ مند ہے کیونکہ آپ کے پاس ذاتی طور پر ایک ماہر ہے جو آپ کو سیدھا اور تنگ کر سکتا ہے، جب کہ اگر آپ صرف ایک ریکارڈنگ کے ذریعے دیکھ رہے ہیں، تو آپ واقعی خود ہی ہیں۔ اگر آپ اسے فوری طور پر نہیں اٹھا سکتے ہیں، تو آپ صرف بہت سا وقت اور محنت ضائع کرنے جا رہے ہیں اور اس حقیقت سے مایوس ہو جائیں گے کہ آپ کو مطلوبہ تمام جوابات نہیں مل سکتے ہیں۔

- نوجوان شخص، یونیورسٹی کا طالب علم، انگلینڈ |

| " | ہمارے زیادہ تر نوجوان دوسری زبان (ESL) کے طور پر انگریزی پڑھ رہے تھے۔ عام حالات میں، ایسے ماحول میں ہونے کی وجہ سے جہاں وہ اپنے ارد گرد انگریزی سن رہے ہوں – کینٹینوں میں، لائبریریوں میں – وہ زبان کو بہت تیزی سے اٹھانے جا رہے ہیں۔ انگریزی میں اس قسم کی نمائش کے بغیر وہ ممکنہ طور پر مزید دو سے تین سال ESL سیکھ رہے تھے، اس کے مقابلے میں صرف دو سال یا شاید ایک سال بھی، وبائی مرض سے پہلے۔

- بے گھر کیس ورکر، انگلینڈ |

ہم نے والدین اور پیشہ ور افراد سے سنا ہے کہ اہم کارکنوں کے بچے اور اسکولوں کے ذریعے کمزور سمجھے جانے والے بچے لاک ڈاؤن کے دوران اسکول جانے کے قابل تھے۔ والدین اور پیشہ ور افراد نے اسے بچوں کے لیے فائدہ مند پایا۔ تاہم، اساتذہ اور والدین نے نوٹ کیا کہ بہت سے بچوں اور نوجوانوں نے کم ساختہ اسکول کے ماحول کا تجربہ کیا، جو معیاری نصاب کی پیروی نہیں کرتے تھے۔ اس نے کچھ معاملات میں باقاعدہ سیکھنے کی طرف واپسی کو چیلنج بنا دیا۔

| " | ہم نے محسوس کیا کہ ہم بچوں کے لیے دن کی دیکھ بھال فراہم کر رہے ہیں۔ یقینا، ہم والدین کے لیے اس کی حمایت کرنا چاہتے تھے، انہیں کام پر جانے دیں۔ کچھ بھی عام طور پر نہیں چل رہا تھا، لہذا یہ صرف ایک بہت مختلف پروگرام تھا۔ طلباء کی تعلیمی ضروریات کو پورا کرنے کے لیے یہ ہماری پوری کوشش تھی، لیکن بہت زیادہ چیلنجز تھے۔ یہ ایک بہت ہی کم ٹائم ٹیبل تھا، بہت کم سروس جو ہم پیش کرنے کے قابل تھے۔

- ابتدائی سالوں کے پریکٹیشنر، اسکول بھیجیں، شمالی آئرلینڈ |

پیشہ ور اور والدین نے وضاحت کی کہ کمزور بچوں کے لیے ذاتی طور پر اسکولنگ تک رسائی متضاد تھی، کچھ مقامی حکام نے اپنی تعریف میں رضاعی نگہداشت میں بچوں کو شامل نہیں کیا۔ یہ خاص طور پر ان بچوں کے لیے مشکل تھا جو آن لائن سیکھنے میں مشغول ہونے کے لیے جدوجہد کر رہے تھے۔ اس کے برعکس، کچھ بچوں نے اپنے رضاعی خاندان کے ساتھ گھر میں رہنے کو ترجیح دی۔

| " | ہمارے پاس مقامی حکام تھے جنہوں نے اسکولوں میں مرکز کھولے تھے اور اہم کارکنوں کے بچے اندر جا سکتے تھے۔ کچھ مقامی حکام نے کہا کہ دیکھ بھال کرنے والے بچے اندر آ سکتے ہیں۔ کچھ نے کہا نہیں۔ میرے کچھ دیکھ بھال کرنے والے تھے جن کے بچے گھر پر رہتے تھے۔ لیکن، مثال کے طور پر، میرے پاس ہائی اسکول میں دو نوعمر لڑکوں کے ساتھ ایک کیئرر تھا۔ ان میں سے ایک آن لائن اسباق کے ذریعے بیٹھنے میں کامیاب ہوا، دوسرا، اگر دیکھ بھال کرنے والا جسمانی طور پر اس کے ساتھ نہیں بیٹھتا، تو وہ اس کا مقابلہ نہیں کرے گا۔

- سماجی کارکن، ویلز |

اساتذہ نے ہمیں بتایا کہ جیسے ہی اسکول دوبارہ کھلے، CoVID-19 کے سخت اقدامات جیسے 'بلبلز'، ماسک اور دوری پر عمل درآمد مشکل تھا، خاص طور پر چھوٹے بچوں اور SEND والے بچوں کے لیے۔ خود کو الگ تھلگ کرنے کے قوانین کی وجہ سے جاری خلل اور پریشانی کے احساسات پیدا ہوتے ہیں۔

| " | چار سالہ بچے پر ماسک لگانے کی کوشش کرنا سب سے آسان نہیں تھا … ایک اسکول میں سماجی دوری بہت مشکل تھی۔ جب وہ اپنے دوستوں کو دیکھتے ہیں، تو چار سال کے بچوں کو سمجھانا اور انہیں الگ رکھنے کی کوشش کرنا مشکل ہوتا ہے، کیونکہ وہ سمجھ نہیں پاتے۔

- پرائمری اسکول ٹیچر، ویلز |

| " | میرا بیٹا آٹسٹک ہے اس لیے وہ ہر چیز کے بارے میں فکر مند تھا کہ اسکول نے کہا 'آپ کو لوگوں سے بہت دور رہنا ہوگا۔ آپ کو ماسک پہننا ہوگا،' اور اس کی پریشانی چھت سے گزر گئی، لیکن اسکول کا رویہ تھا، 'بس ایسا ہی ہے۔' آپ جانتے ہیں، آپ کو معلوم ہے کہ تمام بچے مختلف ہوتے ہیں، لیکن ساتھ ہی ساتھ کچھ ایسا بھی ہے جس میں مدد کی ضرورت ہے۔

- 8 سالہ بچے کے والدین، شمالی آئرلینڈ |

والدین اور پیشہ ور افراد نے ہمیں بتایا کہ کچھ بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے لیے تعلیمی تبدیلیاں مشکل تھیں۔ اس عرصے کے دوران ابتدائی سالوں یا پرائمری میں شروع ہونے والے بہت سے بچوں کو گھر میں طویل مدت کے بعد دیکھ بھال کرنے والوں سے الگ ہونے میں دشواری ہوتی تھی۔ ثانوی اسکول یا یونیورسٹی میں منتقل ہونے والے طلباء کی منتقلی کی کم تیاری تھی، وہ سماجی اور تعلیمی طور پر موافقت کے لیے جدوجہد کرتے تھے اور منتقلی کے بارے میں فکر مند محسوس کرتے تھے۔

| " | ان کے پاس کوئی عبوری دور نہیں تھا۔ تو، آپ جانتے ہیں، ہم اسکول وغیرہ کے بہت سارے دورے کرتے ہیں، اساتذہ، اپنے ہم جماعتوں سے ملتے ہیں، وغیرہ، جبکہ ایسا کچھ بھی نہیں ہوا۔ تو، یہ بہت، قسم کا، آغاز سٹاپ تھا۔ انہوں نے نرسری ختم کی اور پھر انہوں نے بغیر کسی مرحلے کے یا اس اچھے، طرح کے احساس کے اسکول شروع کیا۔

- ایarly سال پریکٹیشنر، سکاٹ لینڈ |

| " | ہم نے دیکھا کہ ان بچوں پر بہت زیادہ اثر پڑا ہے جو سیکنڈری اسکول میں منتقل ہو رہے تھے، اس لیے ان کے پاس منتقلی کی کوئی معاونت نہیں تھی، جیسا کہ انھیں وبائی مرض سے پہلے کا سامنا کرنا پڑتا تھا۔ سکول کا کوئی دورہ نہیں تھا۔ بچوں کے اس مخصوص گروہ نے شاید اب سیکنڈری اسکول سے گزرتے ہوئے جدوجہد کی ہے کیونکہ ان کے پاس منتقلی نہیں تھی۔

- کمیونٹی سیکٹر ورکر، ویلز |

بہت سے شراکت داروں نے سیکھنے اور ترقی میں بڑے پیمانے پر تاخیر کو بیان کیا۔ ابتدائی سالوں میں، اس میں موٹر مہارت، بیت الخلا کی تربیت، تقریر اور زبان کے مسائل شامل تھے۔ پرائمری اسکول کے بچوں کو ریاضی اور انگریزی جیسے بنیادی مضامین میں دھچکا لگا۔

| " | وہ حقیقت میں تقریباً حسی مسائل کی طرف رجوع کریں گے، جیسے اپنے ہاتھ پینٹ کرنا، انگلیوں کو پینٹ کرنا، وہ تمام حسی چیزیں جن سے وہ چھوٹ گئے تھے، تقریباً بچوں کی طرح۔ یہ ایسا ہی ہے جیسے وہ واپس چھوٹوں اور بچے ہونے کی طرف لوٹ گئے۔ انہوں نے تعلیمی سیکھنے کا بہت بڑا حصہ کھو دیا تھا۔

- چائلڈ ڈویلپمنٹ آفیسر، سکاٹ لینڈ |

| " | جب کہ میرے دونوں بڑے پڑھنے، لکھنے، کرسیو اور ان سب کی بنیادی باتوں کو پہلے ہی سمجھ چکے تھے، جب تک ہم لاک ڈاؤن میں تھے، میرا سب سے چھوٹا جو ابھی شروعات کر رہا تھا، اپنی تعلیم کے اہم ترین مہینے سے محروم ہو گیا تھا، کیونکہ سکول اسی طرح بند ہو گیا تھا جیسے اس نے شروع کیا تھا۔

- 4، 8 اور 11 سال کی عمر کے بچوں کے والدین، انگلینڈ |

وہاں تھے۔ اسکول میں حاضری اور تعلیم کے ساتھ مشغولیت کے مسائل اور یہ وبائی امراض میں خلل کا ایک اہم طویل مدتی اثر رہا ہے۔ اس میں وہ بچے اور نوجوان شامل تھے جو اسکول نہیں جانا چاہتے اور ہوم ورک مکمل کرنے میں دشواریاں تھیں۔ والدین اور پیشہ ور افراد کا خیال تھا کہ یہ مسائل وبائی امراض سے متعلق اضطراب، سیکھنے کے وقفے کی وجہ سے تعلیمی جدوجہد، اور طلباء اور خاندان دونوں کے درمیان تعلیم کی اہمیت کے بارے میں رویوں میں تبدیلی سے منسلک تھے۔

| " | وبائی مرض کے بعد سے اس کی اسکول کی حاضری زیادہ سے زیادہ کم ہو گئی ہے، اور ہم اب بحرانی موڑ پر ہیں۔

- والدین، سکاٹ لینڈ |

| " | روٹین کی تبدیلی، ان بچوں کے لیے جو پہلے سے ہی رویے کے مسائل سے دوچار ہیں، اسکول نہ جانا ان پر بڑا اثر انداز ہوا۔ ان میں سے کچھ، وہ اب بھی جدوجہد کر رہے ہیں۔ مجھے لگتا ہے کہ میرے پاس تقریباً 4 ہیں، میرے کیس لوڈ میں، اب 4 سال ہو چکے ہیں، وہ اس وقفے کی وجہ سے اسکول نہیں گئے جو انہیں وبائی امراض سے ملا تھا۔ لہذا، وہ واقعی باہر جانے اور اسکول جانے کے لیے جدوجہد کر رہے ہیں۔ اس دوران انہیں کچھ بھی پیش نہیں کیا گیا تھا، ایسی کوئی چیز نہیں تھی جو انہیں یہ کہنے کے لیے پیش کی گئی تھی، 'ٹھیک ہے، کیونکہ ان بچوں کو رویے میں مشکلات کا سامنا ہے، یہ کیا ہے کہ انہیں مزید مدد کی ضرورت ہے؟

- سماجی کارکن، انگلینڈ |

ہمیں بتایا گیا کہ وبائی مرض نے تعلیمی حصول کو بھی متاثر کیا۔ کچھ والدین نے اساتذہ کے جائزوں سے گریڈ کی افراط زر کی اطلاع دی۔ اس کے برعکس، کچھ والدین اور پیشہ ور افراد نے اس بات پر روشنی ڈالی کہ ان کے بچوں نے ان کی توقعات سے کم درجات حاصل کیے اور سیکھنے کے وقت کے ضائع ہونے کی طرف اشارہ کیا جس کا مطلب ہے کہ بچے اور نوجوان امتحانات میں اپنی صلاحیتوں تک نہیں پہنچ پاتے۔

| " | اس وبائی مرض نے شاید اسے امتحان کے واقعی سنگین نتائج آنے سے بچایا کیونکہ ظاہر ہے کہ بچوں کو حاصل ہونے والے گریڈ اساتذہ کے جائزوں پر مبنی تھے، اس لیے اس نے اس کے حق میں کام کیا۔

- 16، 18 اور 21 سال کی عمر کے بچوں کے والدین، انگلینڈ |

| " | انہوں نے امتحانات مختلف انداز میں دیے۔ اس لیے، آخر میں اس نے امتحان نہیں دیا، لیکن بدقسمتی سے اسکول نے اس کے لیے جو درجات پیش کیے وہ ان کے مقابلے میں بہت کم تھے، کیا وہ اسکول میں جا رہی تھی یا لاگ ان ہو رہی تھی اور وہ کر رہی تھی جو اسے ہونا چاہیے تھا، یا اسکول سے اس کی توقع تھی۔ لہذا، وہ اپنے GCSEs کے لیے کافی نچلے درجے کے ساتھ آئی۔ اگر کوویڈ نہ ہوا ہوتا اور وہ ہفتے میں 5 دن اسکول جاتی اور کلاسوں میں جاتی، تو وہ اس کورس ورک میں ڈال رہی ہوتی، اور وہ کام کرتی جس کی ضرورت تھی۔

- رضاعی والدین، انگلینڈ |

| " | میں ایسے نوجوانوں کو جانتا ہوں جنہوں نے اپنے امتحانات میں اتنا اچھا نہیں کیا جیسا کہ انہوں نے سوچا تھا، اور وہ کوویڈ پر الزام لگاتے ہیں اور انہوں نے حقیقت میں کتنا سیکھنا چھوڑا ہے، اور اس کا گریڈز پر نقصان دہ اثر پڑتا ہے۔ خاص طور پر نوجوان جو سوچتے تھے کہ وہ خاص طور پر اچھا کام کرنے جا رہے ہیں اور پھر شاید وہ نتیجہ کبھی نہیں ملے جو وہ چاہتے تھے۔ میرے خیال میں یہ ہمارے، قسم کے، نوجوانوں کے پرانے گروہوں کے لیے ایک چیلنج تھا جن کے ساتھ ہم کام کر رہے تھے۔

- سماجی کارکن، سکاٹ لینڈ |

کچھ والدین نے ہمیں بتایا کہ اسکولوں اور طلباء نے اب اپنی تعلیم کے لحاظ سے خاص طور پر پرائمری اسکول کے بچوں کے لیے توجہ حاصل کر لی ہے۔ اس کے برعکس، کچھ اساتذہ اور والدین نے مسلسل غیر حاضری، رویے کے مسائل اور علم میں کمی جیسے جاری اثرات کو بیان کیا۔ ایسے خدشات تھے کہ سیکھنے کے اثرات کی مکمل تصویر آنے والے سالوں میں ہی سامنے آسکتی ہے جب بچے تعلیم کے ذریعے ترقی کرتے ہیں۔

| " | میرے خیال میں یہ خلا اب کچھ حد تک بند ہو گیا ہے۔ میرے خیال میں پرائمری بچوں کے لیے خاص طور پر اس خلا کو ختم کرنا آسان تھا۔ پرائمری اسکول کے ذریعے تعلیم کی رفتار اتنی تیز نہیں ہے جتنی کہ سیکنڈری اسکول کے ذریعے ہوتی ہے، اس لیے پرائمری اسکول میں جو وقت ضائع ہوتا ہے، مجھے لگتا ہے کہ وہ کافی اچھی طرح سے حاصل کرنے میں کامیاب ہوگئے ہیں۔ ثانوی اسکول میں چھ، سات، آٹھ مختلف مضامین میں کوشش کرنا اور سیکھنا مختلف ہے، جہاں ہر استاد شاید وہ استاد نہ ہو جو آپ کے پاس پہلے تھا، اس لیے ان کے پڑھانے کے طریقے مختلف ہو سکتے ہیں۔ میرے خیال میں پرائمری بچوں کے لیے پکڑنا آسان تھا، بڑے بچوں کے لیے پکڑنے کی کوشش کرنا کچھ زیادہ مشکل تھا۔ میری بھانجی، اس نے واقعی ہائی اسکول میں داخلہ لینے کے لیے جدوجہد کی۔ میرے خیال میں بڑے بچوں کے لیے یہ ایک زیادہ وسیع مسئلہ تھا، لیکن چھوٹے بچوں کے لیے، پرائمری اسکول میں، مجھے لگتا ہے کہ وہ کافی اچھی طرح سے نمٹنے اور پکڑنے میں کامیاب ہو گئے ہیں۔

- 6 اور 10 سال کی عمر کے بچوں کے والدین، سکاٹ لینڈ |

ہم نے سنا ہے کہ کیریئر کے مشورے، کام کے تجربے اور غیر نصابی سرگرمیوں کے نقصان نے بہت سے نوجوانوں کو اپنی مستقبل کی تعلیم اور روزگار کے انتخاب پر غور کرتے ہوئے، سمت یا مدد کے احساس کے بغیر، غیر یقینی محسوس کر دیا۔ کچھ نے تعلیم سے وقفہ لیا اور بعد میں کھوئے ہوئے وقت کو پورا کرنا پڑا۔

| " | یہ واقعی بہت برا تھا، کیونکہ میرے 18 سالہ بچے نے اپنے جی سی ایس ای میں ٹھیک کیا، وہ اپنے لیول 3 انجینئرنگ کے آخری سال میں تھا، اور آج تک، اس نے واقعی اس شعبے میں نوکری کرنے کے حوالے سے اپنی توجہ بحال نہیں کی ہے۔ لہذا، کیونکہ وہ کالج کے اختتام پر اپرنٹس شپ حاصل کرنے یا کوئی ملازمت حاصل کرنے سے محروم رہا، یہ یقینی طور پر اس کے لیے نقصان دہ تھا۔

- 16 اور 18 سال کی عمر کے بچوں کے والدین، انگلینڈ |

| " | میرے ایک بہترین دوست نے یونیورسٹی چھوڑ دی۔ ہم دونوں پروگرامر ہیں - وہ یقیناً مجھ سے بہتر ہے، بہت بہتر ہے، لیکن وہ ابھی نوکری تلاش نہیں کرنا چاہتا۔ میرے خیال میں CoVID-19 نے اسے ہمارے تمام دوستوں میں سے سب سے زیادہ متاثر کیا۔ اس نے اسے ٹرک کی طرح زور سے مارا ہے۔ وہ واقعی ہوشیار ہے، لیکن وہ ایسا ہے، 'میں واقعی میں اس میں سے کچھ نہیں کر سکتا اور میں نہیں چاہتا' … وہ بڑی دنیا میں جانے سے ڈرتا ہے۔

- نوجوان شخص، یونیورسٹی کا طالب علم، ویلز |

| " | مجھے جو تاثرات موصول ہوئے ہیں وہ یہ ہیں کہ وبائی مرض نے یہ احساس پیدا کیا کہ وہ یہ نہیں جانتے کہ وہ کس سمت میں جا رہے ہیں۔ بہت سے لوگ اکثر کہتے ہیں کہ انہوں نے محسوس کیا کہ وہ بالکل کھوئے ہوئے ہیں اور منقطع ہیں، وہ نہیں جانتے تھے کہ وہ کیا کرنا چاہتے ہیں۔ کوویڈ کے دوران دستبردار ہونے سے، لوگوں کے لیے دوبارہ متحد ہونا واقعی مشکل تھا۔

- سماجی کارکن، انگلینڈ |

خدمات سے مدد تک رسائی حاصل کرنا

والدین اور پیشہ ور افراد نے ہمیں بتایا کہ لاک ڈاؤن کے دوران، بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے لیے صحت کی دیکھ بھال تک رسائی میں کافی حد تک خلل پڑا، جس کی وجہ سے انتظار کے طویل اوقات اور معمول کے چیک اپ سے محروم رہے۔ بہت ساری خدمات دور دراز کے مشورے میں منتقل ہوئیں، والدین نے رپورٹ کیا کہ ان کے بچوں کو ہمیشہ معیاری دیکھ بھال نہیں ملتی۔ کمزور بچوں اور نوجوانوں کو، بشمول صحت کے مسائل کا سامنا کرنے والے اور معذور افراد کو، اضافی چیلنجوں کا سامنا کرنا پڑا۔ بہت سے بچوں اور نوجوانوں کو مختلف حالتوں کے لیے دیر سے مداخلت کا سامنا کرنا پڑا کیونکہ ترقیاتی جانچ پڑتال اور تشخیص میں تاخیر کی وجہ سے۔

| " | "اگر ہیلتھ وزیٹر ہماری اپوائنٹمنٹ پر باہر آیا ہوتا، تو اسے احساس ہوتا کہ اسے یہ مسئلہ اپنے پیروں میں ہے اور ممکنہ طور پر پہلے مرحلے میں اس کو درست کرنے کے لیے اسپلنٹس حاصل کر لیتی۔ ایسا اس لیے نہیں ہوا کیونکہ ہیلتھ وزیٹر اسے دیکھنے کے لیے باہر نہیں تھا، یہ صرف ایک ٹیلی فون انٹرویو تھا۔"

- 1 سالہ بچے کے والدین، شمالی آئرلینڈ |

| " | میری بیٹی کو لاک ڈاؤن کے دوران سانس لینے میں بار بار دشواری ہو رہی تھی اور اس لیے میں نے اپنے جی پی کو فون کیا کہ وہ ملاقات کا وقت اور ایک انہیلر حاصل کریں۔ آخرکار مجھے ریموٹ اپائنٹمنٹ مل گئی، لیکن چونکہ اسے فون پر دمہ کی تشخیص ہوئی تھی، اس لیے وہ مناسب تشخیص کے بغیر انہیلر نہیں دے سکتے تھے۔ میں اس طرح تھا، 'ٹھیک ہے، آپ مجھے بتا رہے ہیں کہ اسے دمہ ہے۔ مجھے انہیلر کی ضرورت ہے۔ وہ اب سانس لینے میں دشواری کر رہی ہے'، اور پھر اس رات وہ دمے کا مکمل دورہ پڑ گئی، اور ہم اس کے نظر آنے سے پہلے A&E میں سات گھنٹے بیٹھے رہے۔

- 2 سالہ بچے کے والدین، سکاٹ لینڈ |

| " | بچے اپنی بصارت کی اسکریننگ سے محروم تھے، اور ہم اسے مکمل نہیں کر سکے، کیونکہ ہم اسکول میں جا کر ان کی اسکریننگ کریں گے کہ آیا انہیں ہسپتال میں ماہر امراض چشم کے پاس جانے کی ضرورت ہے۔ اگر ان کے پاس کوئی بھیانک یا کچھ مختلف ہے، تو ایسا نہ ہونے کا اثر آنکھوں کے کچھ حالات اور کمزور آنکھیں ہو سکتی ہیں جن کی شناخت نہیں ہوسکی… وہ سماعت کے ٹیسٹ نہیں کر پا رہے تھے اس لیے یہ تمام ابتدائی شناخت اور مدد سے بچاؤ کا کام نہیں کیا جا سکا۔

- اسکول نرس، انگلینڈ |

والدین اور پیشہ ور افراد نے دعوی کیا کہ دماغی صحت کی اہم مدد تک رسائی بڑھتی ہوئی مانگ اور دور دراز کی دیکھ بھال کی حدود سے متاثر ہوئی ہے۔ ہم نے سنا کہ کس طرح بچوں اور نوجوانوں کو مدد حاصل کرنے کے لیے خود کو نقصان پہنچانے کے زیادہ خطرہ کے طور پر اندازہ لگایا جانا تھا، بہت سے لوگوں کو ان کی ضرورت کی خدمات کے بغیر چھوڑ دیا گیا تھا۔ پیشہ ور افراد نے ہمیں بتایا کہ کچھ لوگوں کے لیے آن لائن علاج سے متعلق تعلقات استوار کرنا مشکل تھا اور گھر کا ماحول اکثر رازداری کو مشکل بنا دیتا ہے کیونکہ دوسروں کی بات چیت کو سننے کے قابل ہوتے ہیں۔ بچے سے بالغ دماغی صحت کی خدمات میں منتقلی اور بھی زیادہ منقطع ہوگئی۔

| " | اگر کوئی بچہ CAMHS دیکھ رہا ہوتا 3، یا اسکول میں کسی استاد سے، اپنے مسائل کے بارے میں بات کرنے کے لیے، انہیں اب یہ گھر سے کرنا ہوگا۔ جہاں شاید اس میں سے کچھ بدسلوکی اور محرکات گھر میں ہو رہے ہوں … اگر وہ ملاقات چاہتے ہیں یا کسی سے فون پر یا زوم کال پر بات کرنا چاہتے ہیں … جو کہ مثالی نہیں ہے یا ہر ایک کے لیے کام نہیں کرتا … مجھے لگتا ہے کہ بہت سے نوجوان ایسے ہیں جنہیں ان کی حمایت کے لیے مکمل طور پر نظر انداز کیا گیا ہے اور پھر اب ہم اس کے دوبارہ ردعمل دیکھ رہے ہیں۔

- رضاکارانہ اور کمیونٹی گروپ پروفیشنل، ویلز |

سماجی نگہداشت کے پیشہ ور افراد نے یاد کیا کہ کس طرح ذاتی ملاقاتوں پر پابندیاں بچوں کو ان کے گھروں میں دیکھنے یا نجی گفتگو کرنے کی ان کی صلاحیت کو محدود کرتی ہیں۔ کچھ خاندانوں نے بار بار Covid-19 ہونے کا دعویٰ کیا جسے سماجی نگہداشت کے پیشہ ور افراد کو گھر کے دورے کرنے سے روکنے کا بہانہ سمجھا جاتا تھا۔ سماجی نگہداشت کے پیشہ ور افراد کا خیال ہے کہ اس سے بچوں کے بدسلوکی کا انکشاف کرنے کے مواقع کم ہو گئے ہیں اور نظر انداز کرنے کی نشاندہی کرنا زیادہ مشکل ہو گیا ہے، جو ممکنہ طور پر بچوں کی صحت اور نشوونما پر طویل مدتی نقصان دہ اثرات کا باعث بنتا ہے۔

| " | کسی سماجی کارکن کا گھر سے باہر آنا بہت کم ہوتا تھا۔ انہوں نے سماجی کارکنوں کے ساتھ وہی تعلقات نہیں بنائے جو ان کے پہلے تھے۔ ان کے پاس زوم کالز ہوں گی، سماجی کارکنوں کے ساتھ ٹیموں کی کالیں ہوں گی، جہاں ان کی پرائیویسی ایک جیسی نہیں ہے۔ ہمارے کچھ بچوں کو انٹرنیٹ پر مانیٹر کرنا پڑتا ہے … اس لیے عملے کے ایک رکن کو ہمیشہ ان کے ساتھ بیٹھنا پڑتا ہے … ان کے پاس سماجی کارکن کے ساتھ وہ ون ٹو ون وقت نہیں ہوتا تھا جس کی انہیں ضرورت تھی۔

- بچوں کے گھر کا عملہ، انگلینڈ |

| " | اہل خانہ کہیں گے 'مجھے کوویڈ ہے۔ میں دو ہفتے اندر رہوں گا۔' ہم اس گھر کے قریب نہیں جا سکتے … لوگوں نے [کوویڈ کو رابطے سے بچنے کی وجہ کے طور پر] بالکل استعمال کیا ہوگا، اور ہم نے مثبت ٹیسٹ کے لیے زور دیا ہوگا، اور کبھی نہیں ملے گا … 'مجھے کوویڈ ہے، اس لیے آپ دو ہفتوں تک میرے گھر کے قریب نہیں آسکتے ہیں۔' ہم کچھ نہیں کر سکتے تھے۔

- سماجی کارکن، شمالی آئرلینڈ |

زیادہ تر خطرے سے دوچار خاندانوں کو سماجی نگہداشت کی خدمات سے تعاون حاصل کرنے کے لیے ترجیح دی گئی تھی، لیکن اس کا مطلب یہ تھا کہ بہت سے لوگوں کو ابتدائی مداخلت کی مدد نہیں ملی۔ پیشہ وروں کا خیال تھا کہ بچوں کو آن لائن خدمات کے ساتھ مشغول ہونے میں مشکلات کا سامنا کرنا پڑتا ہے کیونکہ گھر میں کم رازداری کے ساتھ غیر ذاتی شکل میں حساس مسائل پر کھل کر بات کرنا مشکل تھا۔ کچھ پیشہ ور افراد نے اطلاع دی کہ انہوں نے باقاعدہ ٹیکسٹس یا کالز کے ذریعے بھروسہ مند تعلقات برقرار رکھنے کی کوشش کی۔

| " | بچے زیادہ خطرے کا شکار تھے کیونکہ وہ دورے جو آپ پہلے کر چکے ہوتے [نہیں ہوئے] … جب آپ ہوم وزٹ کرتے ہیں تو آپ اندازہ لگا سکتے ہیں، دیکھیں کہ والدین بچے کے ساتھ کس طرح جڑے ہوئے ہیں … یہ وہ بچے ہیں جن سے ہم چھوٹ گئے ہوں گے۔ جن بچوں کو ہم نے کمزور کے طور پر شناخت کیا ہوگا ہم نے ان دوروں کی وجہ سے ان کی کمی محسوس کی۔

- ہیلتھ وزیٹر، انگلینڈ |

خصوصی تعلیمی ضروریات اور معذوری (SEND) کی شناخت کرنا مزید مشکل ہو گیا کیونکہ صحت سے متعلق آنے والے اور اساتذہ چھوٹے بچوں میں SEND کی ابتدائی علامات کو دور سے محسوس نہیں کر سکتے تھے۔ اس نے تشخیص کے لیے پیشہ ور افراد کو بروقت حوالہ دینے سے روک دیا۔ ہم نے سنا ہے کہ تشخیص کا انتظار کرنے والوں کو اس سے بھی زیادہ تاخیر کا سامنا کرنا پڑتا ہے، بعض اوقات عمر رسیدہ بچے خدمات سے محروم ہو جاتے ہیں، جیسے کہ ماہر SEND یونٹس۔ صحت کی دیکھ بھال کے پیشہ ور افراد اور والدین نے اس بات پر زور دیا کہ SEND والے بچوں کے لیے ریموٹ سپورٹ خاص طور پر مشکل تھا جنہیں آرام سے مشغول ہونے کے لیے ذاتی بات چیت کی ضرورت ہوتی ہے۔

| " | ہمیں آٹزم کے جائزوں کے لیے اسی طرح حوالہ جات نہیں مل رہے تھے۔ ہمیں اپنے زیادہ تر حوالہ جات اسکولوں سے ملتے ہیں، اس لیے وہ جو ہم پہلے ہی بیچ میں تھے، ہم نے اسے جاری رکھا۔ لیکن اسکولوں کے بند ہونے کی وجہ سے ہمیں کم سے کم ریفرل ملے۔

- معالج، انگلینڈ |

| " | انہوں نے واقعی [آن لائن] مشغول ہونے کے لیے جدوجہد کی، اس لیے ان کا کیس صرف اس لیے بند ہو جائے گا کہ وہ بات نہیں کریں گے، اور [پیشہ ور افراد] کہیں گے، 'وہ مشغول نہیں ہیں، ہمیں کیس بند کرنے کی ضرورت ہے۔' میں نے انہیں بتایا کہ انہیں ذاتی طور پر ملاقات کی ضرورت ہے، لیکن وہ ابھی تک ایسا نہیں کر رہے تھے۔ لہذا، کیس بند ہو جائے گا، اور ہمیں دوبارہ حوالہ دینے کے لیے انتظار کرنا پڑے گا جب وہ کسی کو ذاتی طور پر دیکھیں گے۔ لیکن میں دوبارہ اس ملاقات کے لیے 6 ماہ انتظار کروں گا۔ یہ صرف مایوس کن تھا، کچھ خدمات کے لیے ذاتی طور پر کام کرنے میں واپس آنے میں تاخیر، اس نے کچھ بچوں کی ضروری مدد کی پیشرفت کو متاثر کیا۔

- پادری کی دیکھ بھال کے سربراہ، سکاٹ لینڈ |

صحت اور سماجی نگہداشت کی خدمات دونوں میں پیشہ ورانہ مدد کی فراہمی میں رکاوٹ نے بہت سے احساس کو ترک کر دیا۔ شراکت داروں نے وضاحت کی کہ بچوں اور نوجوانوں نے پیشہ ور افراد اور ان کے تحفظ کے لیے بنائے گئے نظاموں میں عدم اعتماد پیدا کیا۔ پیشہ ور افراد نے ان تجربات کے بچوں اور نوجوانوں کی خدمات کے ساتھ مستقبل کی مشغولیت پر طویل مدتی اثرات کے بارے میں خدشات کا اظہار کیا۔ اگرچہ دور دراز کی ٹیکنالوجیز نے موافقت پذیر شکلوں میں کچھ مدد جاری رکھنے کی اجازت دی، شراکت داروں نے مستقل طور پر کہا کہ وبائی مرض نے ذاتی طور پر اہم اہمیت کو اجاگر کیا، کمزور بچوں اور ان کی مدد کرنے والے پیشہ ور افراد کے درمیان تعلقات پر اعتماد کرنا۔

| " | وہ مدد طلب کرنے اور خدمات تلاش کرنے میں زیادہ ہچکچاتے ہیں، یا ان کو دستیاب کچھ خدمات کے بارے میں بھی علم نہیں ہے۔ میرے خیال میں مایوسی ہے، کیونکہ اب جو بھی خدمات دستیاب تھیں ان کی انتظار کی فہرستیں طویل ہیں، اس لیے وہاں مایوسی ہے کہ لوگوں کو اتنی جلدی نہیں دیکھی جا رہی ہے یا انہیں مطلوبہ علاج نہیں مل رہا ہے۔

- سیکنڈری ٹیچر، ویلز |

جذباتی تندرستی اور ترقی

وبائی مرض نے بچوں اور نوجوانوں کی جذباتی تندرستی اور دماغی صحت پر گہرا اثر ڈالا۔ مختلف پیشوں کے شراکت داروں نے گہری تشویش کا اظہار کیا کہ یہ مسائل وبائی امراض کے آغاز کے بعد سے بڑھے ہیں اور اب بھی برقرار ہیں۔

| " | ہم بہت سے چھوٹے بچوں کو دیکھ رہے ہیں، جن کی عمریں تین سے نو سال ہیں، بہت سنگین جذباتی اور طرز عمل کی حالتوں کے ساتھ جو شاید آپ نے [پری وبائی بیماری] سے پہلے نہ دیکھی ہوں گی۔ ایک تشویش یہ ہے کہ چھوٹے بچوں میں بہت پریشان کن رویہ، انتہائی صدمے والا رویہ ظاہر ہوتا ہے، اور اس کے بارے میں اب کافی بات کی گئی ہے۔

- سماجی کارکن، شمالی آئرلینڈ |

پیشہ ور افراد اور والدین نے اطلاع دی ہے کہ بہت سے بچوں اور نوجوانوں نے وبائی مرض سے پہلے کے مقابلے میں بہت کم عمر میں بھی بے چینی کی اعلی سطح کا تجربہ کیا۔ بچوں اور نوجوانوں کی پریشانی کو مختلف طریقوں سے پیش کیا گیا جس میں اسکول سے انکار اور بال کھینچنا شامل ہیں۔ والدین اور اساتذہ نے اس بات پر روشنی ڈالی کہ کس طرح معمولات میں خلل خاص طور پر نیورو ڈائیورجینٹ بچوں کی جذباتی تندرستی کے لیے مشکل تھا۔ بچوں کے مخصوص گروہ جیسے پناہ کے متلاشی، نگہداشت میں رہنے والے، اور نوجوان مجرموں کو ذہنی صحت سے متعلق پیچیدہ مشکلات کا سامنا کرنا پڑا۔ پیشہ ور افراد نے بتایا کہ کس طرح پہلے سے موجود صدمے میں مبتلا بچوں کو وبائی مرض کے اضافی تناؤ کو تلاش کرنا مشکل ہوا۔

| " | بچے صرف ہنگامہ آرائی میں تھے۔ وہ صرف سمجھ نہیں پائے۔ میں اس کا تعلق ان بچوں سے کر رہا ہوں جن کو سیکھنے میں شدید مشکلات ہیں۔ یہ صرف اتنا ہی جذباتی اثر تھا کہ ان لوگوں کو نہ دیکھ پانا جن کو وہ چاہتے ہیں، ان جگہوں پر نہ جا پانا جہاں وہ کرنا چاہتے ہیں، اپنے معمول کی پیروی نہ کر پاتے۔ مجھے یقین ہے کہ انہوں نے اندر ہی اندر محسوس کیا کہ ان کی پوری دنیا ابھی سمٹ گئی ہے۔

- ابتدائی سالوں کے پریکٹیشنر شمالی آئرلینڈ |

صحت سے متعلق بے چینی پھیلی ہوئی تھی، کچھ بچے CoVID-19، مستقبل کی وبائی امراض اور موت کے بارے میں بہت زیادہ پریشان تھے۔ پیشہ ور افراد اور والدین نے بتایا کہ کس طرح کچھ احتیاطی تدابیر اختیار کرتے ہیں جیسے بار بار ہاتھ دھونا۔ انہوں نے بتایا کہ کس طرح وائرس کے پھیلنے کا خوف بچوں اور نوجوانوں پر بہت زیادہ وزن رکھتا ہے، خاص طور پر نوجوان دیکھ بھال کرنے والوں پر، گھر کے طبی لحاظ سے کمزور افراد اور کثیر نسلی یا نسلی اقلیتی گھرانوں میں جو CoVID-19 سے غیر متناسب طور پر متاثر ہوئے ہیں۔ پابندیوں میں نرمی کے بعد بہت سے لوگوں نے کووڈ 19 اور دیگر جراثیم سے خوفزدہ رہتے ہوئے موافقت کرنے کی جدوجہد کی۔

| " | وہ شدید بے چین تھی۔ وہ متن بھیج رہے تھے جیسے 'آپ کے بچے کی کلاس میں کسی نے کوویڈ کے لئے مثبت تجربہ کیا ہے۔' آخر میں، میں اسے ایک وقت میں کئی دنوں تک سکول نہیں لے جا سکا۔ وہ مسلسل اپنے ہاتھ دھو رہی تھی، اس بات پر اصرار کر رہی تھی کہ گھر پہنچتے ہی اس کی پوری یونیفارم کو دھونا پڑے گا۔ اسے یقین تھا کہ یا تو اس کے والد یا وہ کوویڈ کو گھر لانے جا رہے ہیں اور میں اسے اپنی ماں تک پہنچانے جا رہا ہوں۔ اور اس کے والد کو دمہ ہے، اس لیے یہ ہمیشہ اس کے دماغ میں کھیلتا رہتا تھا۔

- 2، 15 اور 20 سال کی عمر کے بچوں کے والدین، شمالی آئرلینڈ |

| " | ہمارے انتظام کے لحاظ سے، انہوں نے دیکھا کہ ہمیں خاندانوں کے ساتھ آمنے سامنے رابطے کی ضرورت ہے۔ لیکن یکساں طور پر، کچھ [نسلی اقلیتی] خاندان نہیں چاہتے تھے کہ ہم ان کے گھروں میں آئیں یا گھر کا دورہ کریں۔ ہم نے نوٹ کیا کہ ایک خاص گروہ کے بہت سے نوجوان، سیاہ فام لوگ، بہت زیادہ مر رہے ہیں۔ تو اس کے بارے میں بھی کافی پریشانیاں تھیں۔

- کمیونٹی سیکٹر ورکر، انگلینڈ |

بچوں کو تنہائی، کھوئے ہوئے تجربات، اور اپنے غیر یقینی مستقبل کے بارے میں تاریک نقطہ نظر کی وجہ سے کم مزاج کا سامنا کرنا پڑا۔ پیشہ ور افراد اور والدین نے بتایا کہ اس نے کچھ بچوں کے لیے پہلے سے موجود ذہنی صحت کی جدوجہد کو بڑھا دیا ہے۔ مثال کے طور پر، صحت کے کچھ پیشہ ور افراد نے کھانے کی خرابی کی علامات ظاہر کرنے والے بچوں میں تشویشناک اضافہ دیکھا اور ان کا خیال ہے کہ اس سے وبائی امراض کے انتشار کے درمیان بچوں اور نوجوانوں کو کچھ کنٹرول حاصل کرنے کی ضرورت کی عکاسی ہوتی ہے۔ انہوں نے یہ بھی تجویز کیا کہ دماغی صحت کے مسائل، بوریت، اور مجرمانہ استحصال کی وجہ سے منشیات اور الکحل پر انحصار بڑھتا ہے۔ پریشان کن طور پر، والدین اور پیشہ وروں نے ہمیں بتایا کہ کچھ معاملات میں بچوں اور نوجوانوں نے خودکشی کے خیالات کی اطلاع دی، جس پر کچھ نے عمل کیا۔

| " | بہت سارے نوجوان منشیات اور الکحل کی طرف متوجہ ہوئے … اور اب، جو بچے اور نوجوان سسٹم میں آ رہے ہیں، ظاہر ہے کہ ان کی دیکھ بھال کی جائے، یہ تمام مسائل اس وبائی مرض میں ہونے والے واقعات کی وجہ سے ہیں۔

- بچوں کے گھر کی دیکھ بھال کرنے والا کارکن، انگلینڈ |

| " | میرے سب سے بڑے بیٹے کی توقع تھی کہ وہ 16 سال کی عمر میں فٹ بال کلب کی طرف سے اسکاؤٹ ہو جائے گا، لیکن اس کی 16ویں سالگرہ کے فوراً بعد لاک ڈاؤن شروع ہو گیا۔ شدید تربیت کے بغیر کئی مہینوں کے بعد، اس کی فٹنس اور مہارت گر گئی اور اسے لگتا ہے کہ اس نے 'اسے بنانے' کا موقع چھین لیا ہے۔ جس کی وجہ سے وہ ذہنی تناؤ کا شکار ہو گیا۔ اس کے اسکول چھوڑنے سے محروم ہونے کے ساتھ، GCSEs کے برباد ہونے، اس کی گرل فرینڈ کو نہ دیکھ کر، اور اس کی تمام سماجی زندگی ختم ہونے کے ساتھ، اس کے ڈپریشن کی سطح بڑھنے لگی۔ جولائی 2020 کی ایک شام مجھے اس کے دوست کی ماں کا فون آیا کہ وہ خودکشی کی کوشش کرنے کی دھمکی دے رہا ہے اور صبح 2 بجے لکڑی پر نکل گیا ہے۔ شکر ہے کہ اس نے اپنے دوست کو بتایا تھا جو اسے ڈھونڈنے نکلا تھا اور ہم نے فوری طور پر پرائیویٹ طور پر ذہنی صحت کی مدد طلب کی۔

- والدین، انگلینڈ |

والدین اور نوجوانوں نے ہمیں بتایا کہ کس طرح وبائی امراض کا سوگ ناقابل یقین حد تک مشکل تھا، کیونکہ دورہ کی پابندیوں اور جنازے کی پابندیوں نے غم کے تجربات اور ان کی معمول کی موت اور جنازے کے طریقوں کو متاثر کیا۔ سماجی نگہداشت کے پیشہ ور افراد نے نگہداشت میں کمزور بچوں کے بارے میں افسوسناک کہانیاں شیئر کیں جنہوں نے وبائی امراض کے دوران حیاتیاتی والدین کو کھو دیا تھا، کچھ لوگوں کے لیے والدین کی موت کو سمجھنا مشکل تھا جو انہوں نے طویل عرصے میں نہیں دیکھا تھا۔ امدادی خدمات کو متضاد یا ناقابل رسائی کہا جاتا ہے، جس سے بہت سے لوگوں کو ضرورت کی مدد کے بغیر چھوڑ دیا جاتا ہے۔

| " | 17 سال کا ہونا اور اپنی ماں کے ساتھ ایک کمرے میں کھڑا ہونا جو اپنے 13 سال کے شوہر کو کھونے والی ہے۔ ہمیں آخری الوداع کہنے کے لیے اس کے ساتھ اکیلے رہنے کا موقع نہیں دیا گیا … ہم نے محسوس کیا جیسے اس کمرے میں چڑیا گھر کے جانور ہمیں الوداع کہہ رہے ہوں اور متعدد اجنبی نظروں کے ساتھ ہر وقت ہمیں دیکھ رہے ہوں۔

- نوجوان شخص، سکاٹ لینڈ |

جسمانی تندرستی

والدین اور پیشہ ور افراد نے ہمیں بتایا کہ وبائی مرض نے بچوں اور نوجوانوں کی جسمانی تندرستی پر کافی اثرات مرتب کیے ہیں۔ وہ لوگ جو نجی بیرونی جگہ تک رسائی رکھتے ہیں، دیہی علاقوں میں یا باغات کے ساتھ، زیادہ فعال ہونے کے قابل تھے۔ تاہم، بہت سے لوگوں نے گھر کے اندر فعال رہنے کے لیے جدوجہد کی، خاص طور پر چھوٹے گھروں یا عارضی رہائش میں۔ تعاون کرنے والوں نے بتایا کہ پناہ کے متلاشی بچوں کو خاص چیلنجوں کا سامنا کرنا پڑتا ہے، جو اکثر ہوٹل کے کمروں تک محدود رہتے ہیں جن میں کھیلنے کی جگہ نہیں ہوتی۔

| " | میں تین ماہ تک گھر میں اوپر کی منزل کے فلیٹ میں رہا جس میں کوئی باغ نہیں، قدرتی روشنی نہیں، اس نے واقعی میری ذہنی صحت کو متاثر کیا۔ یہاں کے آس پاس بہت سے لوگ ملتے جلتے ہیں اور چھت والے گھروں میں رہتے ہیں، کوئی باغ نہیں۔

- نوجوان شخص، بریڈ فورڈ سننے والا حلقہ |

| " | لاک ڈاؤن کے دوران زیادہ تر لوگوں کو مختصر وقت کے لیے پیدل چلنے یا پارک جانے کی اجازت تھی، لیکن پناہ کے متلاشی ان ہوٹلوں میں پھنس گئے، انہیں باہر جانے یا زیادہ تر لوگوں کے راستے میں چلنے کی اجازت نہیں تھی۔ اور انہیں ہوٹل کے اندر اپنی تمام ضروریات اور سامان ملنا تھا لیکن ایسا نہیں ہوا۔

- رضاکارانہ اور کمیونٹی گروپ پروفیشنل، شمالی آئرلینڈ |

والدین نے اس بارے میں بات کی کہ وبائی مرض کے دوران سرگرمی کی سطح کیسے بدلی۔ کچھ بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے لیے، اسکول بند ہونے، کھیل کے میدان بند ہونے، اور کھیلوں کے کلبوں کے کام بند ہونے سے ان کی سرگرمی کی سطح میں کمی واقع ہوئی۔ بچوں اور نوجوانوں نے زیادہ وقت اسکرینوں کے سامنے بیٹھ کر گزارا، بہت سے لوگوں نے وبائی امراض سے پہلے کی فٹنس کی سطح دوبارہ حاصل نہیں کی۔ نوعمروں کو خاص طور پر باقاعدہ PE کے نقصان سے متاثر کیا گیا تھا۔ اس کے برعکس، کچھ بچے اور نوجوان آن لائن سرگرمی پر مبنی کلبوں تک رسائی حاصل کرکے یا خاندانوں کے ساتھ چہل قدمی کرکے جسمانی طور پر متحرک رہنے کے قابل تھے۔ ہم نے سنا کہ کس طرح کچھ نوجوانوں نے وبائی مرض کے دوران ورزش کو ترجیح دی۔

| " | پہلے ہمارا بیٹا، جو ٹیموں میں باقاعدہ فٹ بال اور کرکٹ کھیلتا ہے، واقعی اپنی فٹنس کے ساتھ جدوجہد کر رہا تھا۔ جب ہم اسکول واپس گئے تو اسے کھیل شروع کرنے سے پٹھوں میں درد ہوا۔ مہینوں میں یہ پہلا موقع تھا کہ وہ اسکول کے میدان میں دوڑ کر اپنے کچھ دوستوں کو دیکھنے کے قابل ہوا ہے۔ لاک ڈاؤن کے دوران، وہ اس کے بجائے ہر روز گھنٹوں آن لائن گیمنگ کرتا تھا۔

- والدین، انگلینڈ |

| " | ہم کافی خوش قسمت تھے، مجھے لگتا ہے کہ ہم نے گولی کو چکما دیا۔ یقینی طور پر لاک ڈاؤن کی پہلی لہر کے دوران، ہم نے اسے قبول کیا۔ ہمارے پاس خوبصورت موسم تھا، خوبصورت باغ تھا، وہ تمام کام کیے جو آپ کے پاس کرنے کا وقت نہیں تھا۔ اس میں سے زیادہ سے زیادہ مثبت چیزیں حاصل کرنے کی کوشش کی، بشمول، آپ جانتے ہیں، بس جو وِکس کے اقدامات اور اس جیسی چیزوں جیسے جنون کے ساتھ بورڈ پر کودنا۔

- 2 اور 8 سال کی عمر کے بچوں کے والدین، انگلینڈ |

ہمیں بتایا گیا کہ کچھ بچوں نے وبائی امراض کے دوران اعلیٰ معیار کے کھانے کا لطف اٹھایا کیونکہ ان کے والدین کھانا پکانے کے لیے گھر پر تھے۔ تاہم، دیگر بچوں اور نوجوانوں نے وبائی مرض کے دوران خوراک کی غربت کی حد سے زیادہ حد تک تجربہ کیا کیونکہ اسکول میں فراہم کیے جانے والے ناشتے اور دوپہر کے کھانے تک ان کی رسائی محدود، یا کھو گئی تھی۔ اس کی وجہ سے بعض اوقات ان کے والدین فوڈ بینکوں پر انحصار کرتے ہیں یا کھانا چھوڑنے جیسی قربانیاں دیتے ہیں۔ کچھ نسلی اقلیتی خاندانوں نے مانوس کھانوں تک رسائی کے لیے جدوجہد کی، جبکہ ہوٹلوں میں پناہ کے متلاشی بچے اکثر غذائیت کا شکار تھے۔

| " | لاک ڈاؤن کے دوران محروم بچوں کے لیے یہ واقعی مشکل تھا، خوراک کی غربت کی حقیقت جس کا وہ سامنا کر رہے تھے اور سپورٹ سسٹم کے نقصان سے۔ اور غذائی عدم تحفظ میں اضافہ ہوا کیونکہ، زیادہ مالی عدم تحفظ کا سامنا کرنا پڑا۔ بہت سارے لوگ فوڈ بینکوں اور اس جیسی چیزوں تک رسائی حاصل کر رہے تھے، اسی طرح عام مدد تک رسائی حاصل کرنے کے قابل نہیں تھے، لہذا ان تمام چیزوں کا ان کی صحت پر بڑا اثر پڑا۔

- معالج، شمالی آئرلینڈ |

| " | پناہ کے متلاشی خاندانوں کو دیئے گئے کھانے کے پارسل ایک حقیقی مسئلہ تھے کیونکہ آپ کے پاس ایسے خاندان ہیں جو صرف حلال کھاتے ہیں، یا وہ مخصوص اوقات میں نہیں کھاتے۔ ظاہر ہے کہ کھانے کے پارسل کے ساتھ، کھانے کی اکثریت تازہ نہیں تھی، یہ لمبی عمر تھی، اور آپ اس بات کی ضمانت نہیں دے سکتے کہ ٹن حلال تھا یا نہیں۔ اس نے اس بات کو یقینی بنایا کہ وہ صحت مند طور پر مشکل کھا رہے ہیں۔

- ہیلتھ وزیٹر، سکاٹ لینڈ |

پیشہ ور افراد اور والدین نے اطلاع دی کہ کچھ بچوں کا وزن بڑھ گیا جس نے ان کی جسمانی صحت کو منفی طور پر متاثر کیا اور، غیر معمولی معاملات میں، ذیابیطس جیسی دائمی حالتوں کا باعث بنے۔

| " | بچے، اوسطاً، شاید اس سے کہیں زیادہ بھاری ہوتے ہیں جتنا وہ وبائی مرض سے پہلے تھے۔ میرے خیال میں یہ بھی ایک قومی موٹاپے کا مسئلہ ہے، لیکن اگر وہ اپنے گھروں میں بند ہیں اور وہ ورزش اور ان تمام چیزوں کے لیے باہر نہیں جا سکتے۔ اس کے بعد انہیں کھانے تک تیزی سے رسائی حاصل ہو گئی ہے جو واقعی میں نہیں ہے [صحت مند] وزن واضح طور پر ایک مسئلہ رہا ہے، اور ظاہر ہے کہ پھر یہ پی ای میں ان کی نقل و حرکت پر اثر انداز ہوتا ہے، جس کا ظاہر ہے کہ ہر چیز پر دستک کا اثر پڑتا ہے۔

- سیکنڈری ٹیچر، سکاٹ لینڈ |

ہم نے سنا ہے کہ کس طرح بچوں اور نوجوانوں کی نیند کے پیٹرن میں خلل پڑتا ہے کیونکہ معمولات تبدیل ہوتے ہیں اور اسکرین کا وقت بڑھتا ہے، وبائی امراض کے بعد مسائل برقرار رہتے ہیں۔

| " | وہ ان آلات پر ہیں، وہ اپنے فون پر ہیں۔ میں نے جو دیکھا وہ نیند کی خراب حفظان صحت کی حقیقی ترقی تھی جہاں نوجوان رات بھر ان آلات پر رہتے تھے اور پھر سارا دن سوتے تھے۔ نیند کی حفظان صحت میں ایک حقیقی انحراف۔

- بچوں کے گھر کا عملہ، شمالی آئرلینڈ |

| " | اس نے میرے سب سے چھوٹے کے لیے نیند کے مسائل پیدا کیے ہیں جو چار سال بعد بھی جاری ہیں۔

- والدین، انگلینڈ |

وبائی مرض کے دوران، بچوں اور نوجوانوں کی دانتوں کی دیکھ بھال تک محدود رسائی تھی، جس کی وجہ سے مسائل، جیسے بوسیدگی، کو حل کرنے کا موقع کم ہو گیا، جس کی وجہ سے بعض صورتوں میں دانت کھو جاتے ہیں۔

| " | میں بچوں کو نرسری میں جاتے ہوئے دیکھ رہا ہوں اور انہوں نے ابھی تک دانتوں کے ڈاکٹر کو نہیں دیکھا ہے، جو دانتوں کے مسائل، دانت نکالنے اور اس جیسی چیزوں کا باعث بن سکتا ہے۔

- ہیلتھ وزیٹر، شمالی آئرلینڈ |

والدین نے مشورہ دیا کہ تنہائی کے دوران بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے عام بیماریوں کے کم ہونے سے قوت مدافعت کم ہوتی ہے اور اسکول واپسی پر بار بار انفیکشن ہوتے ہیں۔ صحت کے پیشہ ور افراد نے یہ بھی اطلاع دی کہ ویکسینیشن کی شرح میں کمی آئی ہے کیونکہ معلومات اور تقرریوں میں خلل پڑا ہے، کچھ علاقوں میں روک تھام کی بیماریوں کے دوبارہ سر اٹھانے کے ساتھ۔

| " | جب ہم نے اپنے [ رضاعی] بیٹے کو نرسری میں واپس بھیجنے کا فیصلہ کیا، تاکہ وہ دوسرے بچوں کے ساتھ مل جل سکے، تو اسے تکلیف ہوئی۔ جیسے، ہر دو ہفتے بعد اسے سینے میں انفیکشن ہوتا تھا۔ اس نے اپنی زندگی کے صحت کے پہلوؤں میں نقصان اٹھایا کیونکہ وہ کسی بھی جراثیم سے محفوظ نہیں تھا۔ تو نرسری میں ان کے پاس جو کچھ تھا، وہ فوراً پہنچ گیا۔

- رضاعی والدین، انگلینڈ |

کووڈ سے منسلک پوسٹ وائرل حالات

ہم نے سنا ہے کہ کس طرح وبائی مرض نے پوسٹ وائرل حالات میں اضافہ دیکھا جس میں بچوں اور نوجوانوں کو متاثر کیا گیا، بشمول کاواساکی بیماری4, پیڈیاٹرک انفلامیٹری ملٹی سسٹم سنڈروم (PIMS)5، اور لانگ کوویڈ6. ان حالات نے ان کی جسمانی اور جذباتی تندرستی پر کافی اور اکثر زندگی بدلنے والے اثرات مرتب کیے ہیں۔

کاواساکی بیماری، جو بنیادی طور پر 5 سال سے کم عمر کے بچوں کو متاثر کرتی ہے، شدید سوزش کا باعث بنتی ہے اور اس سے کورونری اینوریزم جیسی سنگین پیچیدگیاں پیدا ہو سکتی ہیں۔ اس کے علاج کے لیے استعمال ہونے والی دوائیں مدافعتی نظام کو دبا دیتی ہیں، جس سے بچے مزید انفیکشن کا شکار ہو جاتے ہیں۔

| " | اس کی طبیعت خراب تھی، اس کے علاج کی وجہ سے، وہ واقعی زیادہ مقدار والے سٹیرائڈز پر تھا، اس کا مطلب یہ تھا کہ اس کا مدافعتی نظام کم ہو گیا تھا… ہم واقعی، اسے کہیں بھی لے جانے کے لیے بے چین تھے۔

- کاواساکی والے بچے کے والدین |

PIMS، CoVID-19 کی ایک پیچیدگی، اسی طرح پورے جسم میں نقصان دہ سوزش کا سبب بنتا ہے۔ والدین نے بتایا ہے کہ کس طرح PIMS والے بچوں کو دل کے مسائل، پٹھوں کی کمزوری، علمی مشکلات اور دماغی چوٹوں کا سامنا کرنا پڑا ہے۔ اثرات اکثر دیرپا اور کمزور ہوتے ہیں۔

| " | وہ اس طرح بات کر رہا تھا جیسے اسے بولنے میں رکاوٹ ہو، اور اس کے ہاتھ کانپ رہے تھے، اور وہ سب سوج گیا تھا کیونکہ اسے سٹیرائڈز دی گئی تھیں، اور اس کے جوتے فٹ نہیں تھے۔ اس کے پٹھے ضائع ہو گئے۔ وہ کچھ بھی نہیں رکھ سکتا تھا. وہ اسے کھانے کے لیے کھانا بھی نہیں رکھ سکتا تھا … اس کی کورونری شریان میں ایک اینوریزم رہ گیا تھا۔

- 4، 8 اور 11 سال کی عمر کے بچوں کے والدین، انگلینڈ |

لانگ کوویڈ نے بچوں اور نوجوانوں کو اس کا تجربہ کرنے والے لوگوں کو مستقل علامات کی ایک وسیع رینج کے ساتھ چھوڑ دیا ہے۔ کچھ کو شدید متلی کا سامنا کرنا پڑا ہے جس کی وجہ سے وزن میں کمی واقع ہوتی ہے، جب کہ دوسروں کو یادداشت میں کمی اور علمی خرابیوں کا سامنا کرنا پڑا ہے جو روزمرہ کے کام کو ایک جدوجہد بنا دیتے ہیں۔

ہم نے کنبہ کے افراد سے سنا کہ کس طرح لانگ کوویڈ نے بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے شناخت کے احساس کو متاثر کیا، یہ بیماری ان کی شناخت کا ایک ناپسندیدہ حصہ بن گئی اور انہیں اپنی مستقبل کی خواہشات کے بارے میں غیر یقینی بنا دیا۔

| " | میری پوتی [جس نے لانگ کووڈ کا معاہدہ کیا تھا] کی کوئی یادیں نہیں ہیں۔ وہ پرانی تصویروں میں خود کو نہیں پہچانتی

- دادا دادی، انگلینڈ، سننے والے ایونٹ کے ہدف والے گروپس |

والدین نے اطلاع دی کہ صحت کی دیکھ بھال کرنے والے پیشہ ور افراد کی غلط تشخیص اور سمجھ کی کمی نے ان چیلنجوں کو بڑھا دیا ہے۔ صحت کی دیکھ بھال کرنے والے کچھ پیشہ ور افراد نے ابتدائی طور پر بچوں کے پوسٹ وائرل حالات کا سامنا کرنے کے امکان کو مسترد کردیا، جس کی وجہ سے تشخیص اور علاج میں تاخیر ہوتی ہے۔ اس کے ساتھ ساتھ، بعض اوقات علامات کو جسمانی بیماری کے حصے کے طور پر تسلیم کرنے کے بجائے ذہنی صحت کے مسائل یا رویے کے مسائل سے غلط منسوب کیا جاتا تھا۔

| " | یہ اتوار کا دن تھا اس لیے پیر کی صبح میں نے جی پی کو کال کی، میں نے پمز کے بارے میں دوبارہ اپنے خدشات کا اظہار کیا، یہ ایک ٹیلی فون کال تھی، اور جی پی نے تجویز کی کہ اینٹی بائیوٹکس کو بہتر چکھنے والی دوا میں تبدیل کر دیں۔

- والدین، انگلینڈ |

تعلیم کے ساتھ مشغولیت پر اثر شدید رہا ہے، بہت سے بچے اپنی علامات کی وجہ سے باقاعدگی سے اسکول جانے سے قاصر ہیں۔ کچھ نوجوانوں نے ساتھیوں کی طرف سے غنڈہ گردی اور تنہائی کا سامنا کرنے کا بیان کیا، جب کہ اسکولوں نے اکثر اپنی ضروریات کو پورا کرنے کے لیے جدوجہد کی ہے، جس کی وجہ سے مزید علیحدگی ہو جاتی ہے۔

| " | وہ اتنا بیمار ہو گیا کہ اسے اپنے کسی امتحان میں بیٹھنے کا موقع نہیں ملا۔ وہ اس وقت تک مکمل طور پر بستر سے بندھا ہوا تھا، اس لیے اس نے کوئی امتحان نہیں دیا… وہ تعلیم حاصل کرنے کی کوشش کر رہا ہے جو اس سے چھوٹ گئی ہے لیکن اس کی ساری توانائی اسی میں لگ جاتی ہے، اگر وہ کالج کا ایک آدھا دن کرتا ہے، تو وہ گھر آتا ہے اور سیدھا بستر پر چلا جاتا ہے اور اس شام اور اگلے دن ساری رات سوتا ہے۔

- 8 اور 14 سال کی عمر کے بچوں کے والدین، سکاٹ لینڈ |

پوسٹ وائرل حالت کے ساتھ زندگی گزارنے کے جذباتی ٹول کو بہت زیادہ بیان کیا گیا ہے۔ بچوں اور نوجوانوں نے شدید اضطراب کا تجربہ کیا ہے، خاص طور پر دوبارہ بیمار ہونے کے آس پاس۔ والدین نے بتایا کہ ان کے بچوں نے تنہائی اور مدد کی کمی کی وجہ سے ڈپریشن اور یہاں تک کہ خودکشی کے خیالات پیدا کیے ہیں۔

| " | انہوں نے دماغی صحت کے سنگین مسائل پیش کیے کیونکہ وہ خوش، سبکدوش، محبت کرنے والے لڑکوں سے چلے گئے جو کہ صرف ناقابل یقین حد تک پراعتماد، ناقابل یقین حد تک ذہین، شیل ہونے، کچھ بھی نہ ہونے، سڑک پر چلنے کے قابل نہ ہونے کی وجہ سے… یہی بیماری ہے، یہی PIMS ہے اور اس نے ان کے ساتھ کیا کیا ہے۔

- 6 اور 7 سال کی عمر کے بچوں کے والدین، انگلینڈ |

سبق سیکھا۔

والدین اور پیشہ ور افراد نے اپنی زندگی کے مختلف شعبوں میں بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے درمیان کبھی کبھی زندگی بدلنے والے اثرات کی عکاسی کی۔ بہت سے شراکت داروں کا خیال تھا کہ یہ ضروری ہے کہ مستقبل میں وبائی امراض کی صورت میں بچوں اور نوجوانوں کی ضروریات کو ترجیح دینے کے لیے مزید کچھ کیا جائے۔ ان کا خیال تھا کہ اس سے ان کی صحت، تندرستی، سماجی مہارتوں اور ترقی پر نقصان دہ اور اکثر دیرپا اثرات کو کم کرنے میں مدد ملے گی۔

| " | آپ بچوں کو دوسرے لوگوں کی حفاظت کے لیے استعمال نہیں کر سکتے۔ بچے معاشرے کے سب سے کمزور لوگ ہیں۔ انہیں تحفظ کی ضرورت ہے۔ ہم دوسرے لوگوں کی حفاظت کے لیے بچوں کے گھیرے کا استعمال نہیں کر سکتے، چاہے وہ دوسرے لوگ بوڑھے کیوں نہ ہوں۔ آپ کے پاس کمبل کے اصول اور رہنما خطوط بھی نہیں ہوسکتے ہیں۔ معاشرہ اتنا نازک ہے۔ خطرات اتنے کم ہیں۔

- سماجی کارکن، انگلینڈ |

ہم نے سنا ہے کہ اسکولوں اور دیگر خدمات کو زیادہ سے زیادہ کھلا رکھنا ضروری ہے۔ انہوں نے اس بات پر بھی تبادلہ خیال کیا کہ کوویڈ 19 وبائی امراض سے سبق حاصل کرتے ہوئے مستقبل کی وبائی امراض کے لیے تعلیمی ترتیبات کو کس طرح بہتر بنایا جا سکتا ہے۔ اس میں صحیح ٹکنالوجی، عملے کی تربیت اور شاگردوں کے لیے معاونت کے ذریعے دور دراز کی تعلیم کی طرف منتقلی کے لیے تیار رہنا شامل ہے۔

| " | مجھے نہیں لگتا کہ کسی بچے کو سکول سے نکالنا چاہیے تھا۔ میں یہ نہیں کہوں گا کہ ان کی تعلیم کو ترجیح دی گئی تھی، کیونکہ ہماری تمام جسمانی حفاظت کو ترجیح دی گئی تھی، اور میں تعلیم کو صرف تعلیمی ترقی کے علاوہ طویل مدتی فوائد کی پیشکش کے طور پر دیکھتا ہوں۔

- سماجی کارکن، ویلز |

سروسز کے بند ہونے یا آن لائن منتقل ہونے سے بچوں اور نوجوانوں کی صحت اور نشوونما پر منفی اثر پڑتا ہے۔ بہت سے پیشہ ور افراد نے اہم ترقیاتی مراحل میں صحت کی دیکھ بھال سمیت ذاتی طور پر خدمات تک رسائی اور مدد کی پیشکش جاری رکھنے کی اہمیت پر زور دیا۔

والدین اور پیشہ ور افراد بھی مستقبل کے وبائی امراض میں کمزور بچوں کے لیے بہتر تعاون چاہتے ہیں، ایک بار پھر ذاتی رابطے کی اہمیت پر زور دیتے ہیں۔ اس میں ان خاندانوں کے لیے مربوط مالی اور عملی مدد کی پیشکش شامل ہے جو صرف کمیونٹی تنظیموں اور اسکول کے عملے پر انحصار نہیں کرتے ہیں۔

ہمیں بتایا گیا کہ SEND والے بچوں، نگہداشت میں بچوں اور مستقبل کی وبائی امراض میں فوجداری انصاف کے نظام پر زیادہ توجہ دی جانی چاہیے۔ بہت سے پیشہ ور افراد نے محسوس کیا کہ سماجی خدمات کے ساتھ ذاتی طور پر رابطہ مستقبل کے وبائی امراض میں ذاتی طور پر ہوتا رہنا چاہیے۔

| " | میں صرف کچھ کمزور نوجوانوں کے لیے سوچتا ہوں، ان کی سماجی کام میں شمولیت، اور بھرپور تعاون تھا، اور پھر اچانک لاک ڈاؤن کی زد میں آ گیا اور وہ ڈوری کٹ گئی، اور یہ ایک فون کال تھی۔ ہمارے پاس اس ماحول میں کمزور نوجوان تھے، اور یہ بدقسمتی کی بات تھی کہ انہیں مدد کے لیے وہ رسائی نہیں ملی جس کی انہیں ضرورت تھی۔ کیونکہ ایک فون کال نے انہیں وہ رازداری نہیں دی، اور میرے خیال میں ذاتی طور پر یہ خطرہ مول لینے کے قابل تھا، اگر ایسا دوبارہ ہوا تو سماجی کارکنوں کو ان بچوں کو گھر پر دیکھنا چاہیے۔

- حفاظتی برتری، سکاٹ لینڈ |

درج ذیل صفحات مکمل ریکارڈ کے ذریعے ان تجربات کا مزید تفصیلی بیان فراہم کرتے ہیں۔

- بلبلے طلباء کے چھوٹے گروپ تھے جن کا مقصد کووڈ-19 کی نمائش کو محدود کرنے کے لیے مل جل کر سماجی بنانا اور سیکھنا تھا۔

- SEND انگلینڈ میں استعمال ہونے والی اصطلاح ہے، شمالی آئرلینڈ میں SEN کی اصطلاح استعمال کی جاتی ہے، اسکاٹ لینڈ میں یہ اضافی سپورٹ نیڈز ہے، اور ویلز میں یہ اضافی سیکھنے کی ضرورت ہے۔

- CAMHS بچوں اور نوعمروں کی دماغی صحت کی خدمات ہیں۔

- کاواساکی بیماری - NHS

- پمز | این ایچ ایس نے اطلاع دی۔

- COVID-19 کے طویل مدتی اثرات (طویل COVID) - NHS

مکمل ریکارڈ

تعارف

یہ ریکارڈ وبائی امراض کے دوران بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے تجربات کے بارے میں انکوائری کے ساتھ شیئر کی گئی کہانیاں پیش کرتا ہے۔ کہانیاں ان بالغوں کے ذریعہ شیئر کی گئیں جو اس وقت بچوں اور نوجوانوں کی دیکھ بھال کر رہے تھے یا ان کے ساتھ کام کر رہے تھے۔ وہ بچوں اور نوجوانوں پر وبائی امراض کے اثرات کے بارے میں ایک اہم نقطہ نظر لاتے ہیں۔ مزید برآں، 18-25 سال کی عمر کے بچوں نے وبائی امراض کے دوران اپنے تجربات کے بارے میں کہانیاں پیش کیں۔ ان نوجوانوں میں سے کچھ اس وقت 18 سال سے کم تھے۔

پس منظر اور مقاصد

ایوری سٹوری میٹرز برطانیہ بھر کے لوگوں کے لیے یو کے کوویڈ 19 انکوائری کے ساتھ وبائی مرض کے بارے میں اپنے تجربے کا اشتراک کرنے کا ایک موقع تھا۔ شیئر کی گئی ہر کہانی کا تجزیہ کیا گیا ہے اور متعلقہ ماڈیولز کے لیے تھیمڈ دستاویزات میں تعاون کرتا ہے۔ یہ ریکارڈ انکوائری کو بطور ثبوت پیش کیا جاتا ہے۔ ایسا کرنے سے، انکوائری کے نتائج اور سفارشات کو وبائی امراض سے متاثر ہونے والوں کے تجربات سے آگاہ کیا جائے گا۔

یہ ریکارڈ بچوں اور نوجوانوں پر وبائی امراض کے اثرات کے بارے میں والدین اور پیشہ ور افراد کے خیالات کی عکاسی کرتا ہے۔ 18-25 سال کی عمر کے بچوں نے وبائی امراض کے دوران اپنے تجربات کے بارے میں کہانیاں بھی پیش کیں۔ ان نوجوانوں میں سے کچھ اس وقت 18 سال سے کم تھے۔

انکوائری، چلڈرن اینڈ ینگ پیپلز وائسز کے ذریعے شروع کی گئی تحقیق کا ایک الگ حصہ، بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے تجربات اور خیالات کو براہ راست حاصل کرتا ہے۔ اس دستاویز میں بالغوں کی طرف سے بتائی گئی کہانیاں اہم نقطہ نظر اور بصیرت لاتی ہیں۔ تاہم، یہ نوٹ کرنا ضروری ہے کہ بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے نتائج خود اس ریکارڈ کے نتائج سے مختلف ہو سکتے ہیں۔

UK CoVID-19 انکوائری اس وبائی مرض کے مختلف پہلوؤں پر غور کر رہی ہے اور اس نے لوگوں کو کیسے متاثر کیا۔ اس کا مطلب ہے کہ کچھ عنوانات دوسرے ماڈیول ریکارڈز میں شامل ہوں گے۔ لہذا، ہر کہانی کے معاملات کے ساتھ اشتراک کردہ تمام تجربات اس دستاویز میں شامل نہیں ہیں۔

مثال کے طور پر، والدین اور بچوں کے ساتھ کام کرنے والے پیشہ ور افراد کے تجربات دوسرے ماڈیولز جیسے ماڈیول 10 میں شامل کیے گئے ہیں اور ہر کہانی کے دیگر معاملات کے ریکارڈ میں شامل کیے جائیں گے۔ آپ ہر کہانی کے معاملات کے بارے میں مزید جان سکتے ہیں اور ویب سائٹ پر سابقہ ریکارڈ پڑھ سکتے ہیں: https://Covid19.public-inquiry.uk/every-story-matters

لوگوں نے بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے تجربات کا اشتراک کیسے کیا۔

ماڈیول 8 کے لیے ہم نے بچوں اور نوجوانوں کی کہانیاں جمع کرنے کے کئی مختلف طریقے ہیں۔ اس میں شامل ہیں:

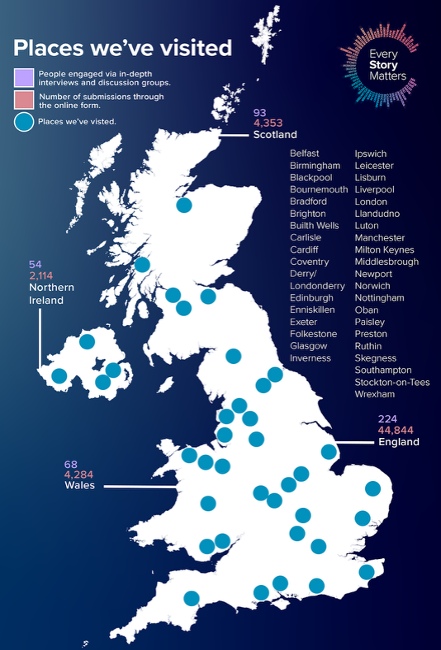

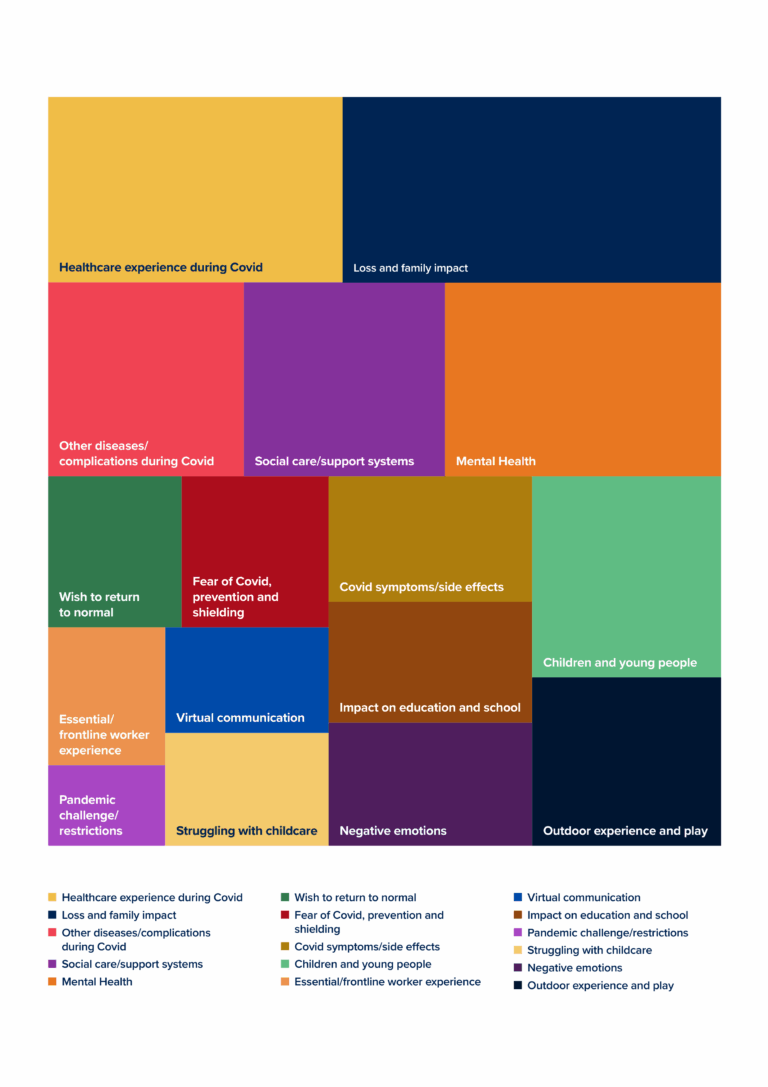

- 18 سال اور اس سے زیادہ عمر کے عوام کے اراکین کو انکوائری کی ویب سائٹ کے ذریعے آن لائن فارم مکمل کرنے کے لیے مدعو کیا گیا تھا (کاغذی فارم بھی شراکت داروں کو پیش کیے گئے تھے اور تجزیہ میں شامل کیے گئے تھے)۔ 18 سے 25 سال کی عمر کے نوجوانوں کی جانب سے وبائی امراض کے دوران اپنے تجربات کے بارے میں کہانیاں پیش کی گئیں۔ وبائی مرض کے وقت ان نوجوانوں میں سے کچھ کی عمر 18 سال سے کم تھی۔ فارم نے شرکاء کو وبائی امراض کے دوران اپنے تجربات کے بارے میں تین وسیع، کھلے سوالات کے جوابات دینے کی دعوت دی۔ اس نے سیاق و سباق فراہم کرنے کے لیے پس منظر کی معلومات بھی اکٹھی کیں، جیسے عمر، جنس اور نسل۔ اس نقطہ نظر نے ہمیں لوگوں کی ایک بڑی تعداد سے سننے کے قابل بنایا اور اس میں وبائی امراض کے دوران بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے تجربات کے بارے میں بہت سی کہانیاں شامل ہیں۔ آن لائن فارم کے جوابات گمنام طور پر جمع کرائے گئے تھے۔ ماڈیول 8 کے لیے، ہم نے 54,055 کہانیوں کا تجزیہ کیا۔ اس میں انگلینڈ سے 44,844 کہانیاں، اسکاٹ لینڈ سے 4,351، ویلز سے 4,284 اور شمالی آئرلینڈ سے 2,114 کہانیاں شامل تھیں (مطالعہ کنندگان آن لائن فارم میں برطانیہ کی ایک سے زیادہ قوموں کو منتخب کرنے کے قابل تھے، اس لیے موصول ہونے والے جوابات کی تعداد سے مجموعی تعداد زیادہ ہے)۔ جوابات کا تجزیہ 'نیچرل لینگویج پروسیسنگ' (NLP) کے ذریعے کیا گیا، جو ڈیٹا کو بامعنی انداز میں ترتیب دینے میں مدد کرتا ہے۔ الگورتھمک تجزیہ کے ذریعے، جمع کی گئی معلومات کو اصطلاحات یا فقروں کی بنیاد پر 'موضوعات' میں ترتیب دیا جاتا ہے۔

اس کے بعد ان موضوعات کا جائزہ لینے والوں نے کہانیوں کو مزید دریافت کرنے کے لیے کیا۔ این ایل پی کے بارے میں مزید معلومات اس میں مل سکتی ہیں۔ اپینڈکس. - اس ریکارڈ کو لکھنے کے وقت، ایوری سٹوری میٹرز ٹیم انگلینڈ، ویلز، سکاٹ لینڈ اور شمالی آئرلینڈ کے 38 قصبوں اور شہروں کا دورہ کر چکی ہے تاکہ لوگوں کو ان کی مقامی کمیونٹیز میں ذاتی طور پر اپنے وبائی امراض کے تجربے کا اشتراک کرنے کا موقع فراہم کیا جا سکے۔ کچھ گروپس نے ورچوئل کالز پر بھی اپنا تجربہ شیئر کیا اگر یہ طریقہ ان کے لیے زیادہ قابل رسائی تھا۔ ٹیم نے بہت سے خیراتی اداروں اور نچلی سطح کے کمیونٹی گروپس کے ساتھ کام کیا تاکہ وبائی امراض سے متاثر ہونے والوں سے مخصوص طریقوں سے بات کی جا سکے۔ ہر ایونٹ کے لیے مختصر خلاصہ رپورٹیں لکھی جاتی تھیں، ایونٹ کے شرکاء کے ساتھ شیئر کی جاتی تھیں اور اس دستاویز کو مطلع کرنے کے لیے استعمال کی جاتی تھیں۔

- سماجی تحقیق اور کمیونٹی ماہرین کے ایک کنسورشیم کو ایوری سٹوری میٹرز نے مختلف بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے تجربات کو سمجھنے کے لیے گہرائی سے انٹرویوز اور ڈسکشن گروپس کرنے کے لیے کمیشن بنایا تھا، جس کی بنیاد پر انکوائری ماڈیول 8 کے لیے کیا سمجھنا چاہتی تھی۔ انٹرویو ایسے بالغوں کے ساتھ کیے گئے جنہوں نے وبائی امراض کے دوران بچوں اور نوجوانوں کی دیکھ بھال کی یا ان کے ساتھ کام کیا اور 21 سال سے لے کر 5 سال تک کی عمر کے نوجوان اور 25 سال کی عمر کے بچے۔ مزید تفصیل میں، اس میں شامل ہیں:

- والدین، دیکھ بھال کرنے والے اور سرپرست

- اسکولوں میں اساتذہ اور پیشہ ور افراد

- صحت کی دیکھ بھال کے پیشہ ور افراد بشمول بات کرنے والے تھراپسٹ، صحت سے متعلق وزیٹر اور کمیونٹی پیڈیاٹرک سروسز

- دوسرے پیشہ ور افراد جو بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے ساتھ کام کرتے ہیں جیسے سماجی کارکنان، بچوں کے گھر کا عملہ، کمیونٹی سیکٹر کے کارکنان اور رضاکارانہ اور کمیونٹی گروپس میں پیشہ ور افراد

- وہ نوجوان جن کی عمریں 18-25 سال کی تھیں وبائی مرض کے دوران اور وہ یونیورسٹی میں جا رہے تھے۔

یہ انٹرویوز ماڈیول 8 کے لیے کلیدی لائنز آف انکوائری (KLOEs) پر مرکوز تھے، جو مل سکتے ہیں۔ یہاں. مجموعی طور پر، انگلینڈ، سکاٹ لینڈ، ویلز اور شمالی آئرلینڈ میں 439 افراد نے ستمبر اور دسمبر 2024 کے درمیان ٹارگٹڈ انٹرویوز میں حصہ ڈالا۔ حصہ لینے والوں نے وبائی امراض کے دوران بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے تجربات پر روشنی ڈالی۔

ان لوگوں کی تعداد جنہوں نے برطانیہ کے ہر ملک میں اپنی کہانیاں آن لائن فارم، سننے والے واقعات اور تحقیقی انٹرویوز اور مباحثہ گروپوں کے ذریعے شیئر کیں۔

شکل 1: ہر کہانی برطانیہ بھر میں مصروفیت کو اہمیت دیتی ہے۔

کہانیوں کی پیش کش اور تشریح

یہ نوٹ کرنا ضروری ہے کہ ایوری سٹوری میٹرز کے ذریعے جمع کی گئی کہانیاں وبائی امراض کے دوران بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے تمام تجربات کی نمائندہ نہیں ہیں۔ وبائی مرض نے برطانیہ میں ہر ایک کو مختلف طریقوں سے متاثر کیا اور جب کہ کہانیوں سے عمومی موضوعات اور نقطہ نظر ابھرتے ہیں، ہم جو کچھ ہوا اس کے ہر کسی کے منفرد تجربے کی اہمیت کو تسلیم کرتے ہیں۔ اس ریکارڈ کا مقصد مختلف اکاؤنٹس کو ملانے کی کوشش کیے بغیر، ہمارے ساتھ شیئر کیے گئے مختلف تجربات کی عکاسی کرنا ہے۔

اس ریکارڈ میں شیئر کیے گئے تجربات 18 سال سے کم عمر کے بچوں یا نوجوانوں نے فراہم نہیں کیے تھے۔. اس کے بجائے، انہیں والدین یا دیکھ بھال کرنے والوں اور بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے ساتھ کام کرنے والے پیشہ ور افراد کے ساتھ ساتھ 18 سے 25 سال کی عمر کے نوجوانوں نے وبائی امراض کے دوران اپنے تجربات کے بارے میں شیئر کیا۔ ان نوجوانوں میں سے کچھ اس وقت 18 سال سے کم عمر کے تھے۔ بالغ، جو والدین یا دیکھ بھال کرنے والے تھے یا جو بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے ساتھ کام کرتے تھے، قیمتی بصیرت پیش کرتے ہیں لیکن یہ اس سے مختلف ہو سکتے ہیں جو وبائی امراض کے دوران بچے اور نوجوان تھے اپنے تجربات کے بارے میں بتاتے ہیں۔

ہم نے ان کہانیوں کی عکاسی کرنے کی کوشش کی ہے جو ہم نے سنی ہیں، جس کا مطلب ہو سکتا ہے کہ یہاں پیش کی گئی کچھ کہانیاں دوسروں سے مختلف ہوں، یا یہاں تک کہ برطانیہ میں بہت سے دوسرے بچوں اور نوجوانوں نے بھی تجربہ کیا۔ جہاں ممکن ہو ہم نے ریکارڈ کو گراؤنڈ کرنے میں مدد کے لیے اقتباسات کا استعمال کیا ہے جو والدین اور پیشہ ور افراد نے اپنے الفاظ میں شیئر کیا ہے۔

ہم نے اس ریکارڈ کے لیے مختلف قسم کے مشکل تجربات سنے۔ پورے ریکارڈ میں، ہم نے یہ واضح کرنے کی کوشش کی ہے کہ آیا تجربات وبائی امراض کا نتیجہ تھے یا پہلے سے موجود چیلنجز جو اس عرصے کے دوران بڑھ گئے تھے۔

کچھ کہانیوں کو مرکزی ابواب کے اندر کیس کی مثالوں کے ذریعے مزید گہرائی میں تلاش کیا گیا ہے۔ ان کا انتخاب ان مختلف قسم کے تجربات کے بارے میں گہری بصیرت فراہم کرنے کے لیے کیا گیا ہے جن کے بارے میں ہم نے سنا ہے اور ان کا بچوں اور نوجوانوں پر کیا اثر پڑا ہے۔ شراکتیں گمنام کر دی گئی ہیں۔

پورے ریکارڈ کے دوران، ہم ان لوگوں کا حوالہ دیتے ہیں جنہوں نے بچوں اور نوجوانوں کی کہانیاں ایوری سٹوری میٹرز کے ساتھ شیئر کی ہیں بطور 'مطالعہ کنندگان'۔ جہاں مناسب ہو، ہم نے ان کے بارے میں مزید بیان کیا ہے (مثال کے طور پر، ان کا پیشہ) ان کے تجربے کے سیاق و سباق اور مطابقت کی وضاحت میں مدد کے لیے۔

جہاں ہم نے اقتباسات کا اشتراک کیا ہے، ہم نے اس گروپ کا خاکہ پیش کیا ہے جس نے نقطہ نظر کا اشتراک کیا ہے (مثلاً والدین یا سماجی کارکن)۔ والدین اور اسکول کے عملے کے لیے، ہم نے خاکہ بھی بنایا ہے۔ ان کے بچوں یا ان بچوں کی عمر کی حدود جن کے ساتھ وہ وبائی امراض کے آغاز میں کام کر رہے تھے۔. ہم نے برطانیہ میں اس قوم کو بھی شامل کیا ہے جس کا تعاون کرنے والا ہے (جہاں سے معلوم ہے)۔ اس کا مقصد ہر ملک میں کیا ہوا اس کا نمائندہ نقطہ نظر فراہم کرنا نہیں ہے، بلکہ CoVID-19 وبائی مرض کے برطانیہ بھر میں متنوع تجربات کو ظاہر کرنا ہے۔

اس ریکارڈ میں بچوں اور نوجوانوں کی کہانیوں کو کس طرح اکٹھا کیا گیا اور اس کا تجزیہ کیا گیا اس کے بارے میں مزید تفصیلات شامل ہیں۔ اپینڈکس.

ریکارڈ کی ساخت

یہ دستاویز قارئین کو یہ سمجھنے کی اجازت دینے کے لیے بنائی گئی ہے کہ بچے اور نوجوان وبائی مرض سے کیسے متاثر ہوئے۔ تمام ابواب میں حاصل کیے گئے بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے مختلف گروہوں کے تجربے کے ساتھ ریکارڈ کو موضوعی طور پر ترتیب دیا گیا ہے:

- باب 2: خاندانی تعلقات پر اثرات

- باب 3: سماجی تعاملات پر اثر

- باب 4: تعلیم اور سیکھنے پر اثر

- باب 5: خدمات سے مدد تک رسائی

- باب 6: جذباتی تندرستی اور ترقی پر اثر

- باب 7: جسمانی تندرستی پر اثر

- باب 8: کووڈ سے منسلک پوسٹ وائرل حالات

- باب 9: سیکھے گئے سبق

ریکارڈ میں استعمال ہونے والی اصطلاحات

دی اپینڈکس کلیدی گروپوں، بچوں اور نوجوانوں سے متعلق مخصوص پالیسیوں اور طریقوں کا حوالہ دینے کے لیے پورے ریکارڈ میں استعمال ہونے والی اصطلاحات اور فقروں کی فہرست شامل ہے۔

براہ کرم نوٹ کریں کہ یہ طبی تحقیق نہیں ہے - جب کہ ہم شرکاء کی طرف سے استعمال کی جانے والی زبان کی عکس بندی کر رہے ہیں، جس میں 'اضطراب'، 'ڈپریشن'، 'کھانے کی خرابی' جیسے الفاظ شامل ہیں، یہ ضروری نہیں کہ یہ طبی تشخیص کا عکاس ہو۔

2 خاندانی تعلقات پر اثرات

اس باب میں دیکھا گیا ہے کہ لاک ڈاؤن نے بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے گھر میں رشتوں اور روزمرہ کی زندگی پر کیا اثر ڈالا ہے۔ یہ بیان کرتا ہے کہ کس طرح دادا دادی یا دیگر بڑھے ہوئے خاندان کے ساتھ وقت گزارنے کے قابل نہ ہونا بچوں اور نوجوانوں کو متاثر کرتا ہے۔ اس باب میں کچھ بچوں کو درپیش چیلنجوں کی بھی کھوج کی گئی ہے، جیسے کہ وہ لوگ جو اپنے پیدائشی خاندانوں کے ساتھ نہیں رہتے، ایسے گھروں میں رہتے ہیں جہاں بدسلوکی ہوتی ہے اور نوجوان دیکھ بھال کرنے والے جنہیں کل وقتی دیکھ بھال کی ذمہ داریاں نبھانی پڑتی ہیں۔

خاندانی حرکیات میں تبدیلی

وبائی امراض کے دوران بچوں نے اپنے گھر والوں کے ساتھ زیادہ وقت گزارا۔ تاہم، والدین اور پیشہ وروں نے یاد کیا کہ کس طرح کچھ بچوں کو اپنے والدین کے ساتھ اضافی معیاری وقت کا فائدہ نہیں پہنچا۔ کچھ والدین جسمانی طور پر موجود تھے لیکن کام کے دباؤ کی وجہ سے اپنے بچوں کے ساتھ زیادہ وقت نہیں گزار سکے۔

| " | وہ سب گھر میں اکٹھے تھے اور والدین اب بھی دور سے کام کر رہے تھے اور بچوں کو کوئی معنی خیز بات چیت کرنے کی بجائے واقعی میں ٹی وی کے ساتھ اسکرین پر ان کے اپنے آلات پر چھوڑ دیا گیا تھا۔

- ہیلتھ وزیٹر، سکاٹ لینڈ |

کچھ والدین جنہیں چھٹی دی گئی تھی انہوں نے بتایا کہ کس طرح ان کے بچوں نے خاندان کے ساتھ اضافی وقت کا فائدہ نہیں اٹھایا، کیونکہ تناؤ، غیر یقینی اور جذباتی تناؤ اکثر والدین کے لیے اپنے بچوں پر توجہ مرکوز کرنے کے لیے توانائی حاصل کرنا مشکل بنا دیتا ہے۔ کچھ خاندانوں کا ڈھانچہ اور معمولات ختم ہو گئے، اور بعض اوقات بچوں اور نوجوانوں کو خود ہی انتظام کرنے کے لیے چھوڑ دیا جاتا تھا۔

| " | وبائی مرض کے دوران مجھے کام سے فارغ کر دیا گیا، مجھے اپنے دو بیٹوں کے ساتھ گھر چھوڑ دیا گیا۔ میرے شوہر ایک اہم کارکن تھے جس کا مطلب تھا کہ مجھے دو چھوٹے بچوں پر قبضہ کرنے کے لیے اکیلا چھوڑ دیا گیا تھا جو کہ مشکل تھا۔

- والدین، انگلینڈ |

| " | میں ایک کام پر کام کر رہا تھا اور ہم سب اپنی نوکریوں سے محروم ہو گئے اور پھر ہم فارغ ہو گئے اور پھر اتنے پیسے نہیں تھے کہ مجھے دوسری نوکری کرنی پڑی… یہ واقعی ایک مشکل وقت تھا۔ میرے پاس آٹسٹک بچے ہیں اس لیے جیسے ہی انہیں اپنے معمولات میں کسی بھی قسم کا کریو بال ڈالا جاتا ہے یہ انہیں مکمل طور پر باہر پھینک دیتا ہے اور جہاں انہیں یقین نہیں ہوتا تھا کہ [میرے کام اور ان کی تعلیم] کے ساتھ ہر ایک دن کیا ہو رہا ہے اس نے کسی بھی معمول پر تباہی مچا دی۔

- 12، 16، 17 اور 18 سال کی عمر کے بچوں کے والدین، انگلینڈ |

بہت سے خاندانوں کو توسیع شدہ خاندان کی طرف سے عملی اور جذباتی مدد کا نقصان بہت مشکل پایا۔ والدین اور پیشہ ور افراد نے اطلاع دی کہ دادا دادی کے ساتھ بچوں کا رابطہ اکثر کھڑکیوں کے دورے، سماجی طور پر دوری کی بیرونی ملاقاتوں اور فون یا ویڈیو کالز تک کم ہوتا ہے۔ اس کا مطلب یہ تھا کہ کچھ بچے اپنے دادا دادی کے ساتھ مضبوط رشتہ قائم کرنے سے قاصر تھے۔ چھوٹے بچے، خاص طور پر، یہ سمجھنے کے لیے جدوجہد کر رہے تھے کہ وہ اپنے دادا دادی کو صرف کھڑکیوں سے ہی کیوں دیکھ سکتے ہیں اور انہیں گلے نہیں لگا سکتے اور نہ ہی جسمانی طور پر چھو سکتے ہیں۔ اس جذباتی رابطہ نے بچوں کی تندرستی اور ان کے وسیع خاندان سے تعلق کے احساس کو متاثر کیا۔

| " | ان کے شاید نانی، نانا نانی کے ساتھ ایک جیسے تعلقات نہیں تھے، کیونکہ وہ اتنے زیادہ نہیں ہوتے تھے اور یہ بڑھے ہوئے خاندانوں کے لیے پوتے پوتیوں اور نئے بچوں اور بڑے پوتے پوتیوں کے ساتھ تعلقات رکھنا ضروری ہے۔ میرے خیال میں بچے صرف یہ نہیں سمجھ سکتے تھے کہ لوگ کھڑکیوں میں کیوں لہرا رہے ہیں اور وہ باہر جا کر گلے نہیں مل سکتے اور اس طرح کی چیزیں نہیں لے سکتے۔ تو، جذباتی طور پر، مجھے لگتا ہے کہ اس نے بچوں کو متاثر کیا، ہاں۔

- ہیلتھ وزیٹر، شمالی آئرلینڈ |

| " | میری بیٹی اپنے دادا دادی کے بغیر ایک بچے سے ایک چھوٹا بچہ بنی اور اسے ایک رشتہ قائم کرنے میں کافی وقت لگا۔

- والدین، انگلینڈ |

معاونین نے ان بچوں کی کہانیاں شیئر کیں جن کے والدین الگ ہو گئے تھے۔ ان بچوں اور نوجوانوں کو کوویڈ 19 کی پابندیوں کی وجہ سے منفرد چیلنجوں کا سامنا کرنا پڑا۔ وبائی پابندیوں کا مطلب یہ تھا کہ وہ اکثر اپنے والدین میں سے کسی کو آمنے سامنے دیکھے بغیر طویل مدت کا تجربہ کرتے ہیں۔ کچھ معاملات میں، ان کا مختلف گھرانوں میں رہنے والے بہن بھائیوں سے ذاتی طور پر رابطہ نہیں تھا۔ اس کی وجہ سے ان بچوں کے لیے اپنے خاندان کے ساتھ تعلقات قائم رکھنا مشکل ہو گیا تھا۔

| " | یہ مشکل تھا کیونکہ میرے والدین طلاق یافتہ ہیں، لہذا ہمارے لئے، آپ کو اپنے بلبلے کے اندر رہنا پڑا. ٹھیک ہے؟ بعد میں یہ واضح کیا گیا کہ طلاق یافتہ خاندانوں کے بچے والدین کے درمیان جا سکتے ہیں۔ کافی دیر تک میں نے اپنے والد کو اس کے نتیجے میں نہیں دیکھا۔

- نوجوان شخص، سکاٹ لینڈ |

| " | جب لاک ڈاؤن ہوا تو بہن بھائیوں میں سے ایک والد کے ساتھ تھا، ایک ماں کے ساتھ، اس لیے وہ پورے وقت کے لیے الگ تھے جو ان سب کے لیے مشکل تھا کیونکہ وہ اکٹھے نہیں رہ سکتے تھے۔

- مزید تعلیم کے استاد، انگلینڈ |

بچوں اور نوجوانوں کے لیے ذمہ داریوں میں اضافہ

والدین اور پیشہ ور افراد نے اطلاع دی کہ وبائی مرض کے دوران کچھ بچوں اور نوجوانوں نے دیکھ بھال کی نئی ذمہ داریاں سنبھال لیں۔ کچھ والدین کے کام کرنے کے انداز مختلف ہونے، بڑھتے ہوئے مالی دباؤ سے نمٹنے، یا خود بیمار ہونے کی وجہ سے، کچھ بچوں کو دیکھ بھال فراہم کرنے کے لیے قدم بڑھانا پڑا۔ خاندانی کھانے پکانے سے لے کر چھوٹے بہن بھائیوں کی دیکھ بھال تک، ان اضافی فرائض نے ان کی صحت اور ان کے خاندان کے ساتھ تعلقات کو متاثر کیا۔

| " | آپ کے کچھ بچے تھے جنہیں مددگار بننا پڑا کیونکہ ان کے چھوٹے بھائی اور بہنیں تھیں اور انہیں ان کی دیکھ بھال کے لیے تقریباً تھوڑا جلدی بڑا ہونا تھا۔

- ابتدائی سالوں کے پریکٹیشنر، انگلینڈ |

| " | اگرچہ میرے بچوں کے ساتھ میرے تعلقات بڑھ چکے ہیں، لیکن میری بیٹی اب بھی کھلے عام اعتراف کرتی ہے کہ وہ مجھ پر بھروسہ نہیں کرتی کیونکہ میں نے اسے لاک ڈاؤن کے دوران اس کے چھوٹے بھائی کی دیکھ بھال کے لیے اکیلا چھوڑ دیا تھا [جب کہ ایک استاد کے طور پر کام کرنے جا رہا تھا] اور میرے پاس اس پر کوئی ردعمل نہیں ہے کیونکہ اگرچہ یہ میری اپنی کوئی غلطی نہیں تھی، وہ درست ہے۔