Sipasî

Em dixwazin spasiya hemû zarok û ciwanên ku beşdarî vê lêkolînê bûne û yên ku alîkariya piştgiriya beşdariya wan kirine bikin. Her wiha spasiyên taybetî ji bo Acumen Fieldwork, The Mix, The Exchange û Core Participants jî tên kirin. Spas ji Save the Children, Coram Voice, YoungMinds, Alliance for Youth Justice, UK Youth, PIMS-Hub, Long Covid Kids, Clinically Vulnerable Families, Article 39, Leaders Unlocked û Just for Kids Law, tevî Children's Rights Alliance for England, ji bo alîkariya we di dema plansazkirin û wergirtina kesên ku ji bo vê lêkolînê hatine vexwendin. Ji bo foruma Children and Young People: em bi rastî jî girîngiyê didin têgihîn, piştgirî û dijberiya we ya li ser xebata me. Têkiliyên we bi rastî jî di şekildana vê raporê de roleke girîng lîstin.

Ev rapora lêkolînê li ser daxwaza Serokê Lêpirsînê hatiye amadekirin. Nêrînên ku hatine diyar kirin tenê yên nivîskaran in. Encamên lêkolînê yên ku ji xebata meydanî derketine holê pêşniyarên fermî yên Serokê Lêpirsînê pêk naynin û ji delîlên qanûnî yên ku di lêpirsîn û danişînan de hatine bidestxistin cuda ne.

1. Destpêk

1.1 Paşxaneya Lêkolînê

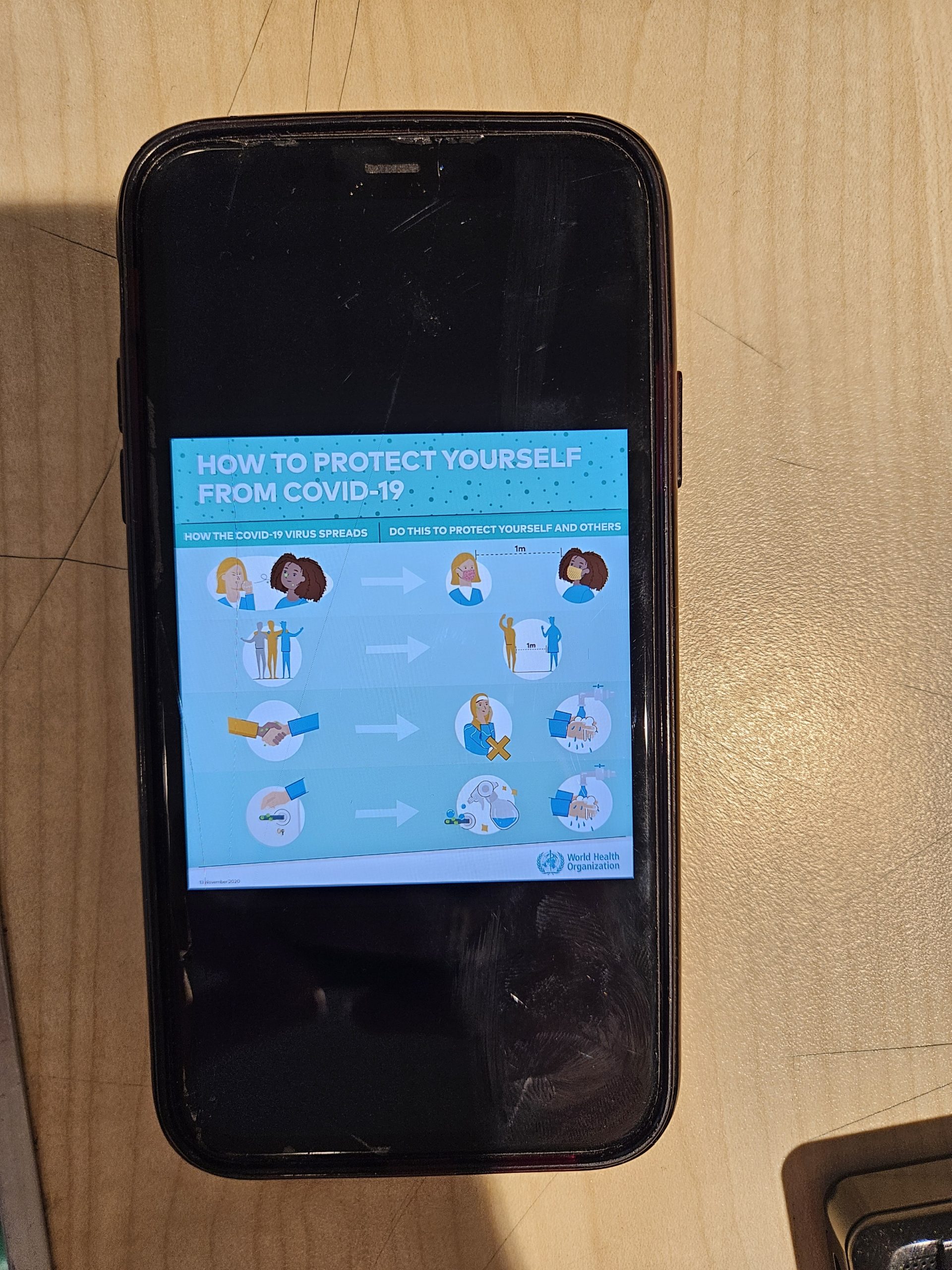

Lêpirsîna Covid-19 a Keyaniya Yekbûyî ("Lêpirsîn") ji bo lêkolîna bersiv û bandora Keyaniya Yekbûyî ya li ser pandemiya Covid-19 û ji bo fêrbûna dersan ji bo pêşerojê hatiye damezrandin. Xebata Lêpirsînê ji hêla wê ve tê rêvebirin. Mercên ReferansêLêkolînên Lêpirsînê li gorî modulan hatine organîzekirin. Modula 8 dê bandora pandemiyê li ser zarok û ciwanan lêkolîn bike.

Lêpirsîna Covid-19 a Keyaniya Yekbûyî Verian erkdar kir ku vê bernameya lêkolînê pêk bîne da ku wêneyek li ser ezmûnên zarok û ciwanan û ka wan bandora pandemiya Covid-19 a Keyaniya Yekbûyî ("pandemî") li ser wan çawa dîtine, peyda bike. Encamên vê raporê dê ji hêla Lêpirsînê ve werin bikar anîn da ku fêm bikin ka zarok û ciwanan çawa li ser guhertinên ku di pandemiyê de qewimîn hîs kirin û bandorên wan çawa jiyan kirin. Ev rapora lêkolînê ne ji bo pêşkêşkirina delîlan li ser ka di vê demê de xizmetguzariyên taybetî çawa guherîn hatine çêkirin. Qadên ezmûna zarok û ciwanan ên ku bi vê lêkolînê ve hatine vekolandin ji hêla komek pirsên lêkolînê ve hatine destnîşankirin, ku di Pêveka A de hatine destnîşan kirin.

1.2 Nêzîkatiya Lêkolînê

Rêbaza lêkolînê ji bo vê bernameyê hevpeyvînên kûr bûn.¹ Verian li Keyaniya Yekbûyî 600 hevpeyvîn bi zarok û ciwanan re di navbera 9 û 22 salî de (ku di dema pandemiyê de di navbera 5 û 18 salî de bûn) pêk anîn. Berî û di dema hevpeyvînê de, Verian her wiha komên referansê yên zarok û ciwanan civand da ku di sêwirana rêberên hevpeyvînê, materyalên beşdaran û guhertoyên zarokan-dostane yên encaman de agahdar bike. Wekî din, berî hevpeyvînan nîqaşên komên fokusê bi dêûbav û mamosteyan re hatin kirin da ku di sêwirana materyalên lêkolînê de rêberî were kirin.

Hevpeyvînan rêbazek agahdar a trawmayê bikar anîn da ku piştrast bikin ku beşdarbûn bi xeletî trawmatîzasyonek dubare an tengahiyê çênekiriye. Zarokên 9-12 salî di dema hevpeyvînan de dêûbav an lênêrînerek amade bûn, lê yên 13 salî û jor dikarin vê vebijarkê hilbijêrin ger hewce bikin. Her zarok û ciwanê ku hevpeyvîn pê re hatiye kirin, piştî hevpeyvîna xwe li ser ezmûna xwe anketek bersivê ya kurt a bijarte tije bikin. Agahiyên bêtir li ser rêbaza lêkolînê, di nav de hevkarên ku piştgiriyê didin xebata Verian, di Pêveka B de hene.

- ¹Hevpeyvînên kûr teknîkeke lêkolîna kalîteyî ne ku behsa birêvebirina nîqaşên berfireh bi hejmareke kêm ji beşdaran re di formata axaftinê de dike. Pirsên hevpeyvînê bi piranî vekirî ne da ku têgihiştin bi awayekî xwezayî derkevin holê, ne ku li gorî planeke hişk tevbigerin.

1.3 Nimûneya Lêkolînê

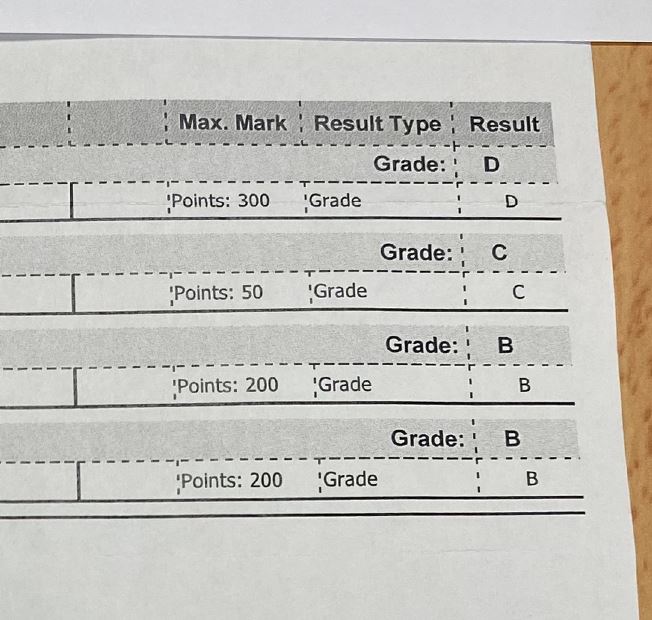

600 hevpeyvînên ku ji hêla Verian ve hatine kirin, ji 300 hevpeyvînan pêk hatine ku bi nimûneyek 'giştî' ya beşdaran re ku bi berfirehî nifûsa Keyaniya Yekbûyî nîşan didin, û 300 hevpeyvînan bi nimûneyek 'armanckirî' ya komên taybetî yên ku li gorî delîlên ku ew bi taybetî ji hêla pandemiyê ve bi awayekî neyînî bandor bûne hatine hilbijartin. Divê were zanîn ku hin zarok û ciwan ji bo bêtirî yek ji van koman pîvanên beşdarbûnê bicîh anîne (li jêr Wêne 1 binêre). Mînakî, piraniya kesên ku daxwaza penaberiyê kirine di heman demê de di wargehên demkî an qerebalix de bûn. Piraniya kesên ku bi pergala dadweriya cezayî re di têkiliyê de bûn, di heman demê de bi karûbarên tenduristiya derûnî û lênêrîna civakî ya zarokan re jî di têkiliyê de bûn.

Wêne 1: Hevberdana di navbera koman de di nimûneya hedefgirtî de

1.4 Çarçoveya vê raporê

Ev rapor encamên hevpeyvînên kûr ên di bernameya lêkolînê ya Dengên Zarok û Ciwanan de destnîşan dike. Ev encam ji bo alîkariya Lêpirsînê hatine çêkirin da ku fêm bikin ka zarok û ciwanan çawa li ser guhertinên ku di dema vê pandemiyê de çêbûne hîs kirine û çawa wan jiyan kirine. Ew ê di destnîşankirina deverên sereke ji bo analîz û nirxandina bêtir de û piştgirîkirina Lêpirsînê di pêkanîna armancên xwe de bibin alîkar. Mercên Referansê.

Raport bi nîqaşkirina faktorên sereke yên ku di dema pandemiyê de wekî şekildana ezmûnên zarok û ciwanan hatine destnîşankirin dest pê dike. Piştî vê yekê, rapor vedigere ser lêkolînek berfireh a ezmûnên ku zarok û ciwanan parve kirine, dest bi guhertinên di hawîrdora wan a malê û têkiliyên malbatî de di vê demê de dike, berî ku derbasî bandorên pandemiyê li ser aliyên din ên jiyana wan bibe, di nav de perwerde, tevgerên serhêl, tenduristî û rehetî. Nîva duyemîn a raporê li ser ezmûnên hawîrdor û karûbarên taybetî di dema pandemiyê de disekine.

Ev ne rapora Serokê Lêpirsînê ye û encamên wê yên Serok pêk naynin. Şîrovekirina encaman û nîqaşkirina encamên wê, yên tîma lêkolînê ya Verian in.

Ev Çîrok Girîng e, temrînek guhdarîkirinê ya cuda ye ku ji hêla Lêpirsînê ve tê kirin. Qeyda Ev Çîrok Girîng e, serpêhatiyên zarok û ciwanan bi perspektîfa mezinên di jiyana wan de yên ku lênêrîn an piştgirî dane tomar dike. Ciwanên ji 18 salî mezintir jî beşdarî qeyda Ev Çîrok Girîng e. Girîng e ku were zanîn ku nêrînên mezinan di derbarê serpêhatiyên zarok û ciwanan de dibe ku li hin deveran ji encamên vê raporê cuda bin.

1.5 Rêbername ji bo xwendevanan

Nirx û sînorkirinên lêkolîna kalîteyî

Ji bo ku têgihîştineke kûr li ser ezmûnên zarok û ciwanan di dema pandemiyê de were peyda kirin û dengê wan were zindîkirin, ji bo vê lêkolînê rêbazeke kalîteyî hate pejirandin. Lêkolîna kalîteyî ji bo lêkolîna nuwazeyên ezmûnan îdeal e; ew derfetê dide beşdaran ku ezmûnên xwe bi hûrgilî parve bikin û cîh dide wan ku li ser motîvasyon û hestên xwe bifikirin. Rêbazên kalîteyî dema ku diyardeyên civakî yên tevlihev têne lêkolîn kirin bi qîmet in û ji bo danasîn û şîrovekirina wan bi kûrahî hatine çêkirin, dewlemendiya hûrgiliyan peyda dikin.

Rêbazên kalîteyî ji bo pîvandina pirbûn an belavbûna ezmûnek an têkiliyekê nehatine sêwirandin. Wekî din, nimûneyên kalîteyî bi mebest têne sêwirandin da ku ezmûnên komên taybetî bigirin, bi pîvanên berfireh ên wergirtina beşdaran. Ji ber vê yekê lêkolîna kalîteyî ji bo pêşkêşkirina encamên temsîlî yên îstatîstîkî nehatiye sêwirandin û nikare heman asta giştîkirinê wekî daneyên hejmarî peyda bike. Li gorî vê yekê, dema ku têgînên wekî 'hin' di rapora lêkolîna kalîteyî de têne bikar anîn, ev bi nirxek hejmarî ya taybetî ve ne girêdayî ne. Divê her weha were zanîn ku mînakên taybetî yên ezmûnên takekesî dibe ku nûner nebin. Lêbelê, lêkolîna kalîteyî dikare were bikar anîn da ku têgihîştinek li ser spektrumek ezmûn û perspektîfên mirovan bi awayekî pêşkêş bike ku rêbazên hejmarî nikarin.

Lêkolîna kalîteyî jî amûrek bihêz e dema ku bi daneyên hejmarî û formên din ên delîlan ve were sêgoşekirin. Ev rapor vê sêgoşekirinê pêk nayne. Lêbelê, sêgoşkirina bêtir a dîtinên wê dikare bi taybetî di peydakirina çarçoveyek li ser spektruma ezmûnên ku bi awayekî kalîteyî têne vegotin de bikêr be, li cihê ku daneyên piştgirî an delîlên li ser belavbûna van hene.

Têbînîyek li ser termînolojiyê

Peyva 'zarok û ciwan' di tevahiya vê raporê de tê bikar anîn da ku bi hev re behsa kesên ku ji bo vê lêkolînê hatine hevpeyvîn kirin bike. Lêbelê, li cihê ku têkildar be, em peyva 'zarok' an 'zarok' bikar tînin da ku behsa kesên ku di dema hevpeyvînê de ji 18 salî piçûktir bûn bikin. Em peyva 'ciwan' an 'ciwan' bikar tînin da ku behsa kesên ku di dema hevpeyvînê de 18 salî an mezintir bûn bikin. Divê tê fêmkirin ku behsa dêûbavan lênêrînvan û parêzvanan jî di nav xwe de digire. Gotinên ji zarok û ciwanan temenê wan di xala hevpeyvînê de vedihewîne, û di hin rewşan de (ji bo kesên ku hewcedariyên perwerdehiyê yên taybetî hene û yên ku di dema pandemiyê de di hawîrdorên taybetî de ne) agahdariya girîng a kontekstî li ser rewşa wan nîşan dide da ku alîkariya têgihîştina bersiva wan çêtir bike. Ji ber ku ji beşdaran nehat xwestin ku roja jidayikbûna xwe bidin, ne mimkûn e ku temenên Adara 2020-an bi domdarî werin destnîşankirin. Wekî din, ji ber ku hin ezmûnên ku hatine vegotin salan didomînin, girêdana van vegotinan bi temenê wan di destpêka pandemiyê de dikare şaş be. Verian bi taybetî ji zarok û ciwanan li ser ezmûnên wan ên ji 2020-22 pirsî, ji ber vê yekê rapor dema borî bikar tîne. Lêbelê, girîng e ku were zanîn ku ji bo hin ciwanên ku me bi wan re axivî, rewşa wan û bandora Covid-19 heta roja îro jî berdewam dike.

Hişyariya naverokê

Hin ji çîrok û mijarên ku di vê tomarê de cih digirin, danasînên mirinê, serpêhatiyên nêzîkî mirinê, îstismara cinsî, êrîşa cinsî û zirara girîng a fîzîkî û psîkolojîk dihewînin. Ev dikarin xemgîn bin. Ger wusa be, xwendevan têne teşwîq kirin ku li gorî hewcedariyê ji hevkar, heval, malbat, komên piştgiriyê an pisporên tenduristiyê alîkariyê bixwazin. Lîsteyek ji xizmetên piştgirî di heman demê de li ser malpera Lêpirsîna Covid-19 a Keyaniya Yekbûyî jî tê peyda kirin.

2. Faktorên ku ezmûna pandemiyê şekil dan

Ev beş faktorên ku pandemiyê ji bo hin zarok û ciwanan bi taybetî dijwar kirine, û faktorên parastinê û sivikkirinê yên ku alîkariya hin zarok û ciwanan kirine ku li hember vê pandemiyê bisekinin û hetta geş bibin, dide nasîn.

Di hevpeyvînan de, ne kêm bû ku vegotinên zarok û ciwanan ên li ser pandemiyê bi tevahî erênî an neyînî bin. Hin kesan pandemiyê bi hestên tevlihev ve girêdidin - mînakî, dibe ku ew ji ber neçûna dibistanê di destpêkê de xwe bi nisbeten kêfxweş û azad hîs bikin, lê paşê xwe bêhêvî û tenê hîs bikin. Hin zarok û ciwanan behsa dijwarîyên ku di dema pandemiyê de pê re rû bi rû mane kirin, lê di heman demê de hîs kirin ku aliyên erênî yên ezmûnê an jî bi kêmanî tiştên ku ji wan re bûne alîkar ku li hember wê bisekinin hene. Ji ber vê yekê, vê lêkolînê cûrbecûr ezmûnan tomar kir û ev spektruma bersivê di tevahiya vê raporê de tê nîşandan.

Li ser bingeha vê yekê, analîza me hejmarek faktorên ku pandemiyê ji bo hin kesan bi taybetî dijwar kirine û her weha faktorên ku di vê demê de alîkariya zarok û ciwanan kirine ku xwe li hember wê tehemûl bikin, destnîşan dike.

Wêne 2: Faktorên ku ezmûnên pandemiyê şekil dane

| Faktorên ku pandemiyê ji bo zarok û ciwanan dijwartir kir | Faktorên ku alîkariya zarok û ciwanan kirin ku li hember bisekinin û pêş bikevin |

|---|---|

| Tansiyona li malê | Têkiliyên piştgirî |

| Giraniya berpirsiyariyê | Dîtina rêbazên piştgiriya başbûnê |

| Kêmbûna çavkaniyan | Kirina tiştekî bi xêr |

| Tirsa zêdebûyî | Kapasîteya berdewamiya fêrbûnê |

| Sînorkirinên zêdekirî | |

| Astengkirina piştgiriyê | |

| Ezmûna şînê |

Hin ji kesên ku hevpeyvîn pê re hatiye kirin, ji ber tevlîheviya faktorên neyînî yên li jor hatine rêzkirin, bandor bûne, nemaze ew kesên ku ji bo nimûneya hedefgirtî hatine hilbijartin û ew kesên ku pîvanên beşdarbûnê ji bo ji yekê zêdetir ji komên hedefgirtî bicîh anîne. Di hin rewşan de, ezmûna wan a pandemiyê bi giranî neyînî bû û hebûna têkiliyên piştgir ji bo sûdwergirtinê û rêbazên lênêrîna refaha xwe bi taybetî girîng bû.

Li jêr em faktorên ku serpêhatiyên pandemiyê ji bo zarok û ciwanan şekil dane bi berfirehî vedikolin. Me ji bo ronîkirina van lêkolînan li seranserê gotarê kirine. Ev ji vegotinên takekesan hatine girtin, navên wan hatine guhertin.

Faktorên ku pandemiyê dijwartir kirin

Li jêr em faktorên ku pandemiyê ji bo hin zarok û ciwanan dijwar kirin destnîşan dikin. Di hin rewşan de, bandorbûna ji hêla kombînasyona van faktoran ve bandora pandemiyê li ser zarok û ciwanên ku di heman demê de gelek dijwarî jiyan kirin girantir kir. Zehmetiyên ku ew pê re rû bi rû man dikarin ji ber têkiliya van faktoran jî girantir bibin, wek mînak astengkirina piştgiriyê dema ku li malê dijwarîyên nû an zêde dibin.

Zarok û ciwan di gelek rewşan de dikarin bi wan zehmetiyên ku li jêr hatine vegotin re rû bi rû bimînin, her çend kêmbûna çavkaniyan bi taybetî bandor li wan kesên di malbatên kêmdahat de kir. Divê were zanîn ku hin ji van faktoran bi awayekî zelal bi rewşên taybetî ve girêdayî bûn ku di wergirtina kar de hatine destnîşankirin - mînakî, ji ber ku di malbateke klînîkî ya xeternak de ne, hem ji hêla qedexeyên zêde û hem jî ji hêla tirsa zêde ve bandor bûn. Di hin rewşan de, kesên ku hevpeyvîn pê re hatiye kirin pîvanên du an bêtir komên hedefgirtî bicîh anîn û di encamê de di dema pandemiyê de bi gelek zehmetiyan re rû bi rû man, mînakî xwedî berpirsiyariyên hem lênêrîn û hem jî parastinê, an jî bi hem xizmetên tenduristiya derûnî û hem jî lênêrîna civakî ya zarokan re di têkiliyê de bûn.

Tansiyona li malêRageşiya li malê pandemiyê ji bo hin zarok û ciwanan dijwar kir. Di hin rewşan de, ev ji pandemiyê berê ve çêbû û bi qedexeya derketina derve girantir bû, di heman demê de di hin rewşan de dema ku her kes li malê bi hev re asê mabû, nemaze li cihên ku qada jiyanê teng hîs dikir, rageşî derket holê. Zarok û ciwanan bandora nîqaşkirin an jî nerehetbûna bi xwişk û birayên xwe an dê û bavên xwe re an jî şahidiya rageşiya di navbera mezinan de di malê de vegotin. Ev rageşî tê vê wateyê ku ji bo hin kesan, mal her gav wekî cîhek ewle an piştgir di dema pandemiyê de nayê dîtin, ku ev faktorek girîng bû ji bo ku meriv bikaribe bi qedexeya derketina derve re mijûl bibe.

| Hest bi malbatê re girtîbûnê

Alex, 21 salî, rave kir ku ji bo malbata wê çiqas dijwar bû ku li malê bi hev re asê bimînin, di demekê de ku her kes bi serxwebûn û cîh ve hatibû ragirtin. Di dema qedexeya derketina derve de têkilî xirab bûn. "Ew pir stresdartir bû ji ber ku em hemî bîst û çar demjimêran di bin heman banî de bûn, berevajî, hûn dizanin, ez û xwişka min diçûn, ez diçûm zanîngehê, ew diçû dibistanê… li ser hev diman… Wê demê ne tiştê ku me dixwest bû, me neçar ma ku em dem bi hev re derbas bikin… dê û bavê min bîst û çar demjimêran di heman malê de bûn, dibe ku ji bo wan jî ne baş be… Xwişka min bi dê û bavê min re li hev nedikir û ez û xwişka min jî dibe ku pir baş li hev nedikirin." Têkçûna zewacê di dema pandemiyê de Sam, 16 salî, şahidiya hilweşîna zewaca dê û bavê xwe di dema pandemiyê de kir. Piştî vê yekê, diya wê bi tenduristiya xwe ya derûnî re têkoşîn kir û Sam dît ku her tiştê ku li malê diqewimî bandor li ser başî û têkiliyên wê dikir, ji ber ku ew ji hevalan dûrtir bû. "Ez difikirim ku [pandemî] dibe ku yek ji sedemên sereke bû ku dê û bavê min ji hev veqetiyan… Ez difikirim ku ew tenê neçar bûn ku bêtir dem bi hev re derbas bikin û ez difikirim ku herduyan fêm kirin ku ev ne ramana çêtirîn bû… Wan pirtir nîqaş kirin lê dîsa jî ew pir nîqaş kirin… Ger Covid nebûya, ez nafikirim ku ew ê ji hev veqetiyana… û dûv re… Ez nafikirim ku [diya min] dê pirsgirêkên tenduristiya derûnî hebin… Ez difikirim ku hin ji [hevalên min], mîna, nêzîkî malbata xwe bûn… ne ewqas ji min re." |

Giraniya berpirsiyariyêHin zarok û ciwanan di dema pandemiyê de berpirsiyariyên li malê girtin ser xwe. Ji bilî hilgirtina barê karên pratîkî yên ku diviyabû bihatana kirin, wek lênêrîna kesekî nexweş, lênêrîna xwişk û birayan, an dezenfektekirina kirîna kesekî ku ji hêla klînîkî ve xeternak bû, hinan jî giraniya hestyarî ya piştgiriya malbata xwe di vê demê de hîs kirin, nemaze li cihên ku mirovên li derveyî malê nikaribûn werin û alîkariyê bikin. Hin ji wan ji hêla hişmendiya li ser zehmetiyên ku mezinan dikişînin ve jî bandor bûn, di nav de xirabûna tenduristiya derûnî, fikarên li ser darayî û ezmûnên şînê. Ev rûbirûbûna berpirsiyariya mezinan û stresê tê vê wateyê ku hin zarok û ciwan di dema pandemiyê de "zû mezin bûn".

| Ji berpirsiyariyên lênêrînê revîn tune ye

Robin, 18 salî, di dema pandemiyê de zehmetiyên lênêrîna diya xwe, ku dê û bavê wê tenê ye, vegot. Wekî zaroka yekane, ew bi girtina vê berpirsiyariyê ve hatibû hînkirin, lê di demên normal de dibistanê hinekî ji berpirsiyariyên wê yên li malê rehetî da wê. Di dema qedexeyê de li malê asê mabûn û li hember vê yekê zehmetî kişand, û her wiha tenduristiya derûnî ya diya wê xirabtir bû. Wê vegot ku ew "ji hêla hestyarî ve bêhêz" e û bi giraniya berpirsiyariyê re têdikoşe. "Ez hîs dikim ku eger jiyana te ya malê ne pir baş be, wê demê dibistan ji bo te xilaskariyek mezin e ji ber ku ev tê vê wateyê ku tu tevahiya rojê ji wê jîngehê derkevî û dema ku tu li wir î, tu hevalên xwe dibînî... Ez depresyonê de bûm ji ber ku min, wekî, bêhna xwe ji rewşa xwe ya malê negirt. Û ew mîna gelek berpirsiyariyê li ser milên min her dem e... ew mîna ku li dibistanê ew, wekî, bêhnvedanek ji wê bû û ew balkişandinek pir baş bû. Ji ber vê yekê dema ku ew çû, ew derbeyek pir mezin bû ji ber ku ew rêya min a li hember kar bû... Wê li malê mijûlbûna bi diya min re dijwartir kir... ew mîna barekî giran ê hestyarî bû û ez bi gelemperî xwedî şiyana mijûlbûna bi wê re me û pê re mijûl bibim lê ne dema ku tu her dem li wir asê mayî." Bi stresa mezinan re rû bi rû maye Riley, 22 salî, di dema pandemiyê de li malê bi dê û bavê xwe re dijiya. Ev demek dijwar bû ji bo malbatê ji ber ku diya wan ji hêla klînîkî ve xeternak bû û xwişk û birayê wan, ku ji malê derketibû, bi tiryakê re têdikoşiya. Jiyana ewqas nêzîk di dema qedexeya derketina derve de - "wekî ku hûn di tencereyek zextê de ne" - wan xist ber stresa ku dê û bavên wan dikişandin û wan vegotin ku dest bi parvekirina vê yekê kirine li şûna ku êdî xwe wekî zarok hîs bikin. "Her kes pir ditirsiya. Ji ber vê yekê wê hingê hebûna wê celeb fikara komê… Ez hîs dikim ku min neçar ma ku [dê û bavê xwe] bibînim, mîna, bêtir wekî mirovan ne tenê, mîna, 'oh dêya min her gav ji min aciz dike ku ez vê yekê bikim'… Ji ber ku ez, mîna, wê, her dem… bi awayên pir xeternak didît ji ber, mîna, çiqas her kes stresdar bû. Ew mîna… [Ez] wekî mezinan bi dê û bavê xwe re dicivîm.” |

Kêmbûna çavkaniyanNebûna çavkaniyên derveyî ji bo hin zarok û ciwanên ji malbatên bi çavkaniyên darayî yên sînordar, li hember pandemiyê zehmettir kir. Jiyana di xanîyên qerebalix de ji hesta "li ser hev" tengezarî çêkir û li hember Covid-19 di malê de an jî parastina endamên malbatê yên klînîkî yên xeternak dijwartir kir, û her weha dîtina cîhê ji bo kirina karên dibistanê dijwar kir. Nebûna gihîştina domdar a cîhazan an girêdanek înternetê ya pêbawer jî fêrbûna li malê dijwartir kir, û her weha derfetên girêdana bi yên din re, rihetbûn an jî fêrbûna tiştên nû li ser înternetê sînordar kir. Her çend zarok û ciwanên bê cîhê derve bi piranî vê yekê wekî pirsgirêk neanîn ziman, yên ku baxçeyek wan heye rêbazên zêdekirina refahê û kêfê vegotin ku yên bê baxçe nikarîbûn biceribînin.

| Zehmetiyên fêrbûna serhêl

Jess, 15 salî, di dema pandemiyê de ji bo berdewamiya fêrbûna li malê zehmetî kişand. Wê bi xwişk û birayê xwe re kompîturek kevn parve dikir û Wi-Fi-ya wê pir navber bû, ku di dema dersên serhêl de dibe sedema bargiraniyek xirab û tê vê wateyê ku ew nikarîbû bi rêkûpêk beşdar bibe. Wê wêneyek² ya xwe bi xwe re anî ku li ber komputerê rûniştiye ji ber ku ev bîranînek pir xurt a pandemiyê ji bo wê bû: "[Min ev wêne anî hevpeyvînê] ji ber zehmetiyên serhêlbûnê. Bê guman, wekî, derengmayîn, Wi-Fi dîn bû… [Ez û birayê min] kompîturek hevpar hebû. Dibistanê tiştek neda me… ew, wekî, gelek xeletî dikir ji ber ku Wi-Fi xirab bû û dûv re, wekî, komputer jî pir kevn bû… Perwerde ne baş bû… Em dikarin çi, wekî, bicîh bînin da ku zirarê kêm bikin?… Komputeran peyda bikin. Erê. Komputer û girêdana înternetê ya çêtir peyda bikin.” Cih ji bo xebatê tune Cam, 15 salî, ji bo wê yekê ku jiyana li karantînê "hinekî zêde" ye, ku ew bi dê û bav û du xwişk û birayên xwe re di xaniyekê de dijî, û ew bi wan re odeyek razanê parve dikir. Ew bi wê yekê ve hatibû hînkirin ku carinan hinekî tengav be, lê bi zehmetiyên hewildana fêrbûna malê di cîhekî piçûk de nehatibû hînkirin, ku wê ev yek pir dijwar dît: "Bi taybetî ji ber ku me tenê yek maseyek hebû, mîna maseyek baş. Ji ber vê yekê pir dijwar bû ku meriv hevsengiyê bike ka kî dikare maseyek hebe û kî dikare biçe erdê û bixebite. Ji ber ku carinan ne hewceyî maseyê bû. Ew tenê mîna kişandinek li erdê bû an tiştek wisa. Lê hevsengkirina wê dijwar bû." |

- ² Ji zarok û ciwanên ku beşdarî hevpeyvînan dibûn hat xwestin ku, eger ew xwe rehet hîs bikin, tiştek, wêneyek an wêneyek ku pandemiyê tîne bîra wan bi xwe re bînin. Piştre wan ev yek di destpêka hevpeyvînê de parve kirin û rave kirin ka çima wan ew hilbijart.

Tirsa zêdebûyîZarok û ciwanên seqetên laşî û yên bi pirsgirêkên tenduristiyê, an jî yên di malbatên klînîkî yên xeternak de, hestên xwe yên nezelaliyê, tirs û fikaran li ser xetera girtina Covid-19 û bandorên cidî - û di hin rewşan de jî jiyanê tehdît dikin - ku ev dikare ji bo wan an jî hezkiriyên wan hebe, vegotin. Zarok û ciwanên di hawîrdorên ewle de jî dema ku di dema pandemiyê de bi kesên din re qadên hevpar parve dikirin, xwe xeternak û ji girtina Covid-19 ditirsin. Di dema pandemiyê de şîna kesekî/ê jî dikare bibe sedema hestên tirsê yên zêde.

| Ji ber mirina Covid-19ê bi hêrs in

Lindsey, 15 salî, "ditirsiya" ku dapîra wê, ku bi wê re dijiya, dê bi Covid-19 bikeve. Wê berê hestên fikaran kişandibû û hîs dikir ku ev yek di dema pandemiyê de pir giran bû dema ku xetere ji bo wê ewqas tirsnak bûn. Ev tirs dema ku ew piştî karantînaya yekem vegeriya dibistanê zêde bû. "Li wir gelek karantîneyên me hebûn ku diçûn û dihatin… 'em dikarin vegerin, niha em nikarin', ew tenê wekî, çima em diçin û tên dema ku hîn jî xetereyek mezintir li wir heye?'… Ez her gav ji dibistanê dihatim, tiştê ku digotin dikir, destên xwe dişom, dezenfekte dikir, carinan cilên xwe diguherand da ku ez bikaribim nêzîkî [dapîra xwe] bibim… Ez difikirim ku yek an du [heval] hinekî dûr ketin û her gav dipirsin, 'hûn ji bo çi vê dikin?' 'Çima hûn vê dikin, ne hewce ye ku hûn bikin', ew ne hewce ne ku li ser tiştê ku ez neçar bûm xemgîn bibin." Covid-19 ji nêz ve Elî, 20 salî, di dema pandemiyê de demkî li otêlekê dijiya û li penaxwaziyê digeriya. Jê re odeyek bi sê kesên din re hat dayîn, ku wî hêvî nedikir. Parvekirina odeyek piçûk bi xerîban re di demên herî baş de jî teng bû - "cihê kesane pir tune" - lê tirsa girtina Covid-19 ji hev, an jî ji ber hebûna di cîhên hevbeş ên qerebalix ên otêlê de, ezmûn bi taybetî dijwar kir. "Min nizanibû ku ez ê mîna heman odeyê parve bikim... Her tiştê ku hûn lê dixin, divê em li ser bifikirin... hûn ê li ser her tiştî zêde bifikirin... heman tişt dîsa û dîsa tenê serê we tevlihev kir. Divê hûn dakevin jêr [ber bi kafeteryayê] û dûv re ez gelek kesan dibînim, hûn ê li rêzê bisekinin... dibe ku hûn ji kesekî din Covid bigirin. Stres bû... [Dema ku Covid li min hebû] germahî, serêş, tenê hîs dikir ku tevahiya laşê min xirab bûye... dema ku ez bi sê kesan re odeyek parve dikir, ku qet ne hêsan bû... Wan hûn nexistin odeyek cûda an tiştek din." |

Sînorkirinên zêdekirîDi hin rewşan de, zarok û ciwan ji ber rewşa xwe ji ber sînorkirinên cuda an jî dijwartir ji yên din bandor bûn. Ji bo hin kesan ev ji ber seqetbûna laşî an jî hebûna rewşek tenduristiyê bû, nemaze dema ku girtina destavên giştî sînordar dikir ka ew çiqas dikarin ji malê derkevin an çiqas dûr dikarin biçin. Ji bo hin kesan, ji ber ku ew bi xwe, an jî di malbateke ji hêla klînîkî ve xeternak de bûn, tê wateya ku bi sînorkirinên zêde re mijûl bibin. Ji bo yên din, ev ji ber ku di hawîrdorek ewle an hawîrdorek lênêrînê de bûn û hîs dikirin ku divê ew ji yên din hişktir rêzikan bişopînin bû. Bandorkirina ji sînorkirinên zêde ji bo hin zarok û ciwanan bi taybetî ji hêla hestyarî ve dijwar bû dema ku sînorkirin ji bo yên din hatin sivikkirin û ew xwe ji vê yekê dûrxistî hîs kirin.

| Bi girtina cihên giştî ve sînordar e

Mark, ê 14 salî, rave kir ku çawa rewşa tenduristiya wî dihêle ku derketina ji malê ji bo wî dijwartir bibe dema ku qadên giştî, di nav de tuwalet jî, girtî ne û çawa ew û malbata wî neçar in ku bi baldarîtir plansaz bikin ger ew bixwazin derkevin derve. "Bê guman me kariye bi [rewşa tenduristiya min] re bijîn lê paşê, hûn dizanin, bandorên nû yên wekî dûrbûna civakî, tişt nêzîk dibûn… wê yekê ew pir cûda kir û me neçar ma ku çareseriyên cûda bibînin û bê guman gihîştina cihan dirêjtir digirt, carinan du, sê caran, lê em dîsa jî, em bi rengek digihîştin wir û tenê piştrast dikirin ku, hûn dizanin, tu şansek rastîn tune ye, baş eşkere ye ku şansek heye, lê şansek piçûk a qezayek an tiştek wusa… ew demek pir dijwar bû, nemaze, hûn dizanin, bi pirsgirêkên tenduristiya fîzîkî yên ku min hene, nayê vê wateyê ku ez dikarim tenê biçim cîhek girtî an rasterast biçim destavê an tiştek… nayê vê wateyê ku ez dikarim biçim cîhên girtî… Min hîn jî neçar ma ku rêzikan bişopînim, tenê ji ber ku ez hinekî cûda me nayê vê wateyê ku ez dikarim rêzikan bişkînim." Ji aliyê yên din ve wekî parêzvanekî ciwan hat jibîrkirin Casey, 15 salî, xwişk û birayek heye ku ji hêla klînîkî ve xeternak e. Casey rave kir ku wê çawa di dema pandemiyê de alîkariya parastina xwişk û bira ya xwe kir, çiqas dijwar bû ku piştî karantînaya yekem civak vebû ku xwe biparêze û çawa wê hîs kir ku hewcedariyên wê ji hêla kesên li dora wê ve bi tevahî hatine jibîrkirin. Wê hîs kir ku xuya ye mirov fêm nakin ku ciwan jî xwe diparêzin. "Dema ku em ji [karantînayê] derketin lê dîsa jî ji me dihat hêvîkirin ku em xwe biparêzin… dema ku her kesê din li derve bû û tiştan dikir, xuya bû ku wan kesên ku xwe diparêzin ji bîr kirine, nemaze heke ew ne mîna mirovên pîr bûn… tenê xuya bû ku ew tevdigerin mîna ku her kes vegeriyaye rewşa normal… an jî [wek] ku tenê mirovên ku hîn jî li malê ne mirovên pîr bûn." |

Astengkirina piştgiriyêHin zarok û ciwan di dema pandemiyê de ji ber têkçûna piştgiriya fermî û xizmetên tenduristiyê, nemaze xizmetên tenduristiya derûnî, û her weha ji ber windakirina dibistanê wekî çavkaniyek piştgirî an revîna ji her zehmetiyek li malê bandor bûn. Her çend hin ji wan xwe li windakirina têkiliya rasterast adapte kirin jî, yên din têkiliya bi têlefon û serhêl re dijwar dîtin û xwe kêmtir piştgirî hîs kirin. Kesên ku hevpeyvîn pê re hat kirin her wiha vegotin ku di pirbûn û kalîteya piştgiriyê de derengmayîn û nelihevhatin dîtine û difikirin ku xizmetên ku ew pê ve girêdayî ne di bin zextê de ne. Ev têkçûn dikare ji bo kesên ku jixwe di şert û mercên dijwar de ne, li hember pandemiyê dijwartir bike.

| Nebûna piştgiriya şexsî di krîzeke malbatî de

Charlie ya 20 salî, rave kir ku di dema pandemiyê de dema ku wê hîs kir ku cihê lênêrînê yê lênêrînê têk diçe, ne dîtina xebatkarê xwe yê civakî bi awayekî fizîkî dijwar bû. Wê di axaftinên telefonê de zehmetî kişand ku li ser rewşê eşkere bike û bêriya piştgiriya hestyarî ya ku berê wergirtibû kir. "Ez nafikirim ku Covid sedema hilweşîna cihê karê min bû, lê bê guman ew beşdarî kir... Cihê karê karê xera dibû û ew pir piştrast bûn ku em cihekî karê yê pir xurt in. Ji ber vê yekê min dixwest ku ez vê yekê bidomînim û gazinan nekim... [Bi xebatkara min a civakî re] em bi telefonê diaxivîn lê wê demê wekî ku dêya min a xwedîkirî li wir be. Wekî, me tu carî, yek bi yek dem tunebû ku em li ser hestên xwe bipeyivin... [Berî pandemiyê] ew ê min ji bo şîvê an tiştek wusa bibirina derve... an jî ew ê werin odeya min rûnin û tenê kontrol bikin ka her tişt baş e an jî min ji dibistanê hildin û tiştên wusa tenê da ku hûn hinekî dem bistînin ku hûn biaxivin... Ji ber vê yekê nebûna wê bê guman dijwar bû... [Nebûna] gihîştina terapîst û xebatkarên civakî wekî ku min berî pandemiyê kir, bê guman tê vê wateyê ku ez hinekî bêtir bi ramanên xwe re tenê mam û pir xemgîn bûm." Zehmetiya girtina piştgiriya tenduristiya derûnî bi rêya telefonê George, 20 salî, behsa depresyonê di dema pandemiyê de kir û alîkariya dayika xwe wergirt da ku ji bo terapiya axaftinê sevk bistîne. Berê terapiya rûbirû dîtibû û bi rastî jî zehmetî kişandibû ku bi terapîstekî nû re bi rêya telefonê têkilî dayne. Her çend bi malbata xwe re baş diaxivî jî, ew xwe rehet hîs nedikir ku ji odeya xwe ya razanê ku dengê wê dihat bihîstin biaxive. Piştî çend rûniştinan wê terapi rawestand. "Ez ji gotina tiştan ji malbata xwe re ne dudil im. Lê wekî, mînakî, heke ez bixwazim li ser tiştekî vekim ku ez ne hewce ye ku dê û bavê min bikaribin ji ber wê derbas bibin... û dûv re bibihîzin ku ez tiştekî dibêjim, tiştekî davêjim... Ez tenê hewce dikim ku ew têkiliya fîzîkî, mîna, rû bi rû hebe da ku bi rastî hîs bikim ku ez dikarim ji mirovan re vekim, lê bi rêya telefonê... ew wekî ku bi rastî tu girêdan tune ye, ku ew dikare mîna dengek AI [zanyariya sûnî] be." |

Ezmûna şînêKesên ku di dema pandemiyê de xemgîn bûn, rastî zehmetiyên taybetî hatin ji ber ku qedexeyên pandemiyê rê li ber wan girt ku berî mirina xwe hezkiriyên xwe bibînin, rê li ber wan girt ku wekî ku di demên normal de dikirin şînê bigirin, an jî dîtina malbat û hevalan û hîskirina piştgiriyê di xemgîniya xwe de dijwartir kir. Hin kesan vegotin ku ji bo dîtina hezkiriyek berî mirina xwe, sûcdarî û tirsa şikandina rêzikan, li hember sûcdariya nedîtina wan û tirsa ku ew dikarin bi tenê bimirin, nirxandin. Hin ji wan kesên ku hezkiriyek wan ji ber Covid-19 miriye, şoka zêde ya mirinê ku ewqas zû qewimî, ku wan ji bo xwe û yên din tirsandiye, vegotin.

| Ji ber xemgîniyeke ji nişka ve şok bû

Amy, 12 salî, di dema karantîna yekem de ji ber Covid-19ê hevalekî xwe yê malbatê yê pir hezkirî jiyana xwe ji dest da. Wê şoka xwe ji tiştê ku qewimîbû û çiqas dijwar bû ku meriv pê re mijûl bibe vegot. "Ew gelek caran dihat, mîna dawiya hefteyê û ji bo şîveke biraştî dihat, û her tim diyariyan û şîrînî û tiştên wisa ji min re dianî, û em pir nêzîkî hev bûn, mîna ku ew bi rastî jî mîna dapîr û bapîrek din ji min re bû... Û dû re di dema Covidê de, di dema qedexeyê de, ew bi Covid-19 nexweş ket, û mîna ku ew di teknolojiyê de ne baş bû, ew nedikarî telefonî mirovan bike, ji ber vê yekê... me heta xatir jê xwest jî. Dema ku me dît ku ew miriye, ew pir xemgîn bû, mîna ku ev yek min pir aciz kir... Ez pir ciwan bûm, û min hewl da ku hemî bîranînên xweş bi bîr bînim lê tiştê ku min bi bîr anî ev bû ku ew miriye, û ez ê careke din wê nebînim, û em neçûn merasîma cenazeyê wê ji ber ku qedexe hebûn... cara dawî ku min ew dît, ew tenê wekî 'hefteya bê hev dibînin' bû, û dû re hefteya bê tune bû." |

Bandora gelek faktoran

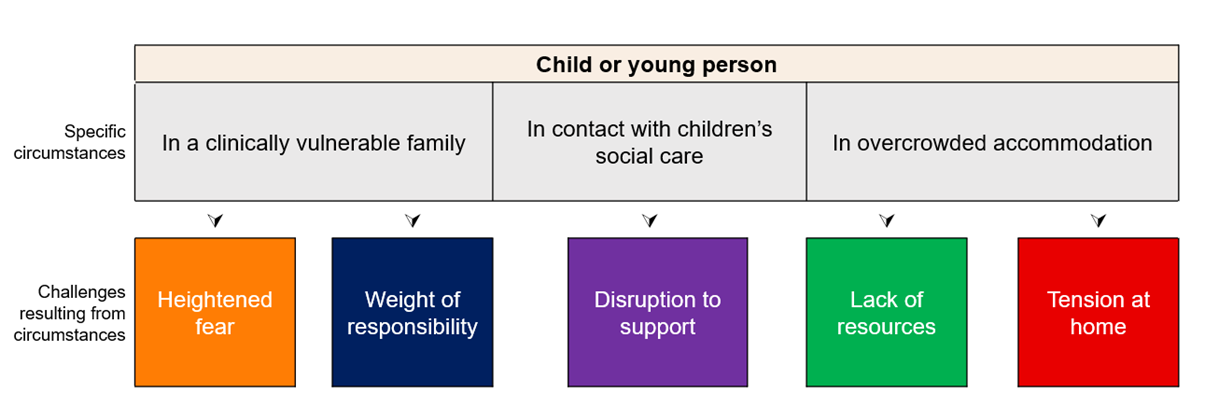

Ev lêkolîn her wiha ezmûnên bandorbûna ji ber gelek pirsgirêkan di dema pandemiyê de li gorî faktorên ku li jor hatine nîqaşkirin tomar kir. Wêneya 3 li jêr nîşan dide ka çawa tevlîheviyek ji şert û mercan di dema pandemiyê de dikare bandorê li kesekî bike - di vê rewşê de jiyana di xaniyek qerebalix de, parastina endamek malbatê yê klînîkî yê xeternak û astengkirina piştgiriya ji lênêrîna civakî ya zarokan. Ev dikare bibe sedema ku zarok û ciwan bi rêzek pirsgirêkan re rû bi rû bimînin ku di dema pandemiyê de jiyan dijwartir kir.

Wêne 3: Bandora potansiyel a gelek faktoran li ser kesekî

Lêkolînên li jêr çend mînakan pêşkêş dikin ku kesên ku hevpeyvîn pê re hatiye kirin ji aliyê kombînasyoneke faktoran û di encamê de bi wan zehmetiyan re rû bi rû mane.

Ev lêkolîna dozê nîşan dide ka çawa ciwanek ku berpirsiyariyên lênêrînê ji bo dêûbavê xwe yê klînîkî yê lawaz girtiye ser xwe, di dema pandemiyê de ji ber giraniya berpirsiyariyê û tirsa zêde bandor bûye.

| Berpirsiyarî û tirsa li hember lênêrîna kesekî klînîkî yê lawaz

Nicky, Di 21 saliya xwe de, zexta ku di dema pandemiyê de hîs dikir dema ku lênêrîna diya xwe dikir, ku piştî veguheztina diya xwe ji hêla klînîkî ve xeternak bû, û "tirsa seqet" ku ew ê bi Covid-19 nexweş bike, vegot. Ji ber ku xwişk û birayê wê yê mezin ji malê dûr dijî û nikare serdana wê bike, berpirsiyarî bi tevahî dikeve ser milê wê. Wê vegot ku hemû kirîn û firotinê girtiye ser xwe, nekariye demek radestkirinê bibîne û ji ber vê yekê bi taksiyê çûye supermarketê û berî ku bîne hundir her tiştî bi baldarî dezenfekte kiriye. Di vê navberê de, diya wê bi xwe jî bi windakirina têkiliya derve re têkoşîn dikir. Nicky xwe di demên normal de wekî kesek berxwedêr didît lê got ku ev yek ji hêla pandemiyê ve hatiye ceribandin, heya wê astê ku wê ji bijîşkê xwe yê malbatê piştgiriya tenduristiya derûnî xwestiye. "Bê guman dema ku ew diya te û kesek e ku tu ji her tiştî bêtir jê hez dikî, tu tenê dikî. Ne pirsa, oh, ez nikarim bi vê yekê re mijûl bibim; divê ez bi vê yekê re mijûl bibim ji ber ku ew hewceyê min e ku ez bikim ... ew ... pir nakok bû ji ber ku ez dixwazim lênêrîna wê bikim lê, di heman demê de, min dixwest ku ez tenê bikaribim, mîna, mirovên din bim û tenê ji razana li ser nivînan û xwendina gelek pirtûkan û temaşekirina gelek TV-yê û bêxembûnê kêfê bistînim." |

Nimûneya jêrîn nîşan dide ka çawa ciwanek bi berpirsiyariyên lênêrînê ku di dema pandemiyê de bi xizmetên civakî re di têkiliyê de bû, ji ber rageşiya li malê û astengiya piştgiriyê bandor bûye.

| Lênêrîna malbatê di navbera hilweşîna malbatê û piştgiriya qels de

Mo, 18 salî, berî pandemiyê berpirsiyariyên lênêrînê hebûn, alîkariya lênêrîna du xwişk û birayên xwe yên xwedî pêdiviyên perwerdehiyê yên taybet dikir û ji ber zehmetiyên wan ên tenduristiyê û îngilîziya wan a kêm, piştgiriya dê û bavê xwe dikir di rêvebirina malê de. Têkiliya dê û bavê wê xirab bû û bavê wê heta wê astê destdirêjî kir ku malbat hewce kir ku ew derkeve, lê dema ku pandemi lê da, cihekî din tunebû ku biçe. Wê behsa giraniya vê rewşê kir. "Wê demê [xizmetên civakî] bi rastî nizanibûn ka çawa pê re mijûl bibin ji ber ku ew digotin, baş e, ew bi rastî nikarin wî ji malê veqetînin ji ber ku cihekî din tunebû ku wî bibin. Ew nikarîbû bi kesekî din re bijî û ew bi xwe jî qels bû… gelek nîqaş hebûn… Xwezî dibistan fêm bikira ka tişt li malê çiqas dijwar in û, hûn dizanin, hebûna zarokekî otîstîk û zarokekî biçûktir bi pirsgirêkên reftariyê yên bi hev re li malê her tim… gelek tişt li ser min bû… Xwezî lênêrîna civakî bi awayekî zirarên ku ji ber girtina bavê min di malê de çêbûne fêm bikira." |

Lêkolîna li jêr nîşan dide ka çawa zarokek ku di dema pandemiyê de bi xizmetên lênêrîna civakî ya zarokan û tenduristiya derûnî re di têkiliyê de bû, di heman demê de li malê bi aloziyan re rû bi rû ma, ji ber astengkirina piştgiriyê bandor bûye.

| Hestkirina windabûna tevlihev a torên piştgirî û karûbaran

Jules, 20 salî, berî pandemiyê ji lênêrînê derketibû û vegeriyabû cem dê û bavê xwe û di rewşek dijwar de bû, û di dawiyê de dîsa ji wir derket. Dema ku pandemiyê dest pê kir, wê fêm kir ku nekarîna bi hevalên xwe re hevdîtinê bike an jî neçe ser karê xwe yê nîv-demî dê bandorek mezin li ser wê bike, nemaze ji ber ku ew jixwe bi tenduristiya xwe ya derûnî re têkoşîn dida. Wê di dema pandemiyê de têkiliya bi lênêrîna civakî ya zarokan re ne lihevhatî dît, her gav ji hêla mirovên cûda ve dihat dîtin, û hîs kir ku divê ew ji bo tenduristiya xwe ya derûnî piştgiriyek çêtir bi dest bixista. "Min tenê difikirî ku ez ê nikaribim hevalên xwe bibînim, ew tora piştgiriyê ya herî mezin e, her gav wisa bûye û dema ku tişt li malê ne baş in tiştê çêtirîn ku meriv bike ev e ku meriv derkeve û hevalên xwe bibîne, ew bi rastî moralê we bilind dike... [Berî pandemiyê] Rojên min ên baş derbas dibûn, ez ê derkevim û hevalên xwe bibînim, tiştên xweş bikim, lê ez hîs dikim ku pandemiyê tenê rojên baş rawestandine... Ez difikirim ku di tevahiya tiştî de bi rastî ti piştgirî tune bû, mîna xebatkarên civakî an PA³ yan tiştekî wisa, ew qet nehatin cem min û negotin 'Ez difikirim ku tu dê ji vê sûd werbigirî' yan tiştekî wisa… kesên ku di bin lênêrînê de ne û yên ku ji lênêrînê derdikevin, wek kesên ku ji lênêrînê derdikevin an jî kesên ku di bin lênêrînê de ne, hin ji wan zarokên herî bêparastin in. Ez hîs dikim ku divê me gihîştineke cuda ji bo xizmetên tenduristiya derûnî hebûya, yan jî, dizanî, derfetên me yên gihîştina piştgiriyê pir zêdetir bûya ji ber ku ez difikirim ku gelek kes dê ji vê yekê sûd werbigirta.” |

- ³ Alîkarên şexsî (PA) piştgiriyê didin kesan ku bi awayekî serbixwe bijîn, bi gelemperî di mala xwe de.

Faktorên ku rê li ber pandemiyê girtin hêsantir kirin

Li jêr em faktorên ku di vê demê de ji bo hin zarok û ciwanan hêsantir kirine ku bi pandemiyê re mijûl bibin, bi dijwarîyan re mijûl bibin û hetta geş bibin, destnîşan dikin.

Têkiliyên piştgirîZarok û ciwanên ji her temenî vegotin ku çawa heval, malbat û civakên berfirehtir alîkariya wan kirine ku ji pandemiyê derbas bibin. Ji bo hin kesan, di hawîrdorek malbatî ya ewle û piştgir de mayîn faktorek girîng bû di afirandina ezmûnên erênî de di dema pandemiyê de. Têkiliya serhêl bi hevalan re jî rêyek hêja bû ji bo şerkirina bêzarî û tecrîda qedexeyê û ji bo zarok û ciwanan ku heke ew di tengasiyê de bin, piştgiriyê bigerin. Hin ji wan di dema pandemiyê de bûn beşek ji civakên nû yên serhêl, ji nasîna lîstikvanên din bigire heya tevlîbûna civatek baweriyê ya nû, û van wekî çavkaniyek piştgiriyê dîtin.

| Girêdana malbatî rehetiyê û hevaltiyê tîne

Jamie ya 9 salî, di dema pandemiyê de bi dê, xaltîk û dapîr û bapîrên xwe re dijiya. Bêyî hevalên ku bi wan re bilîze, ew spasdar bû ku xaltîka wê hevaltiya wê dikir. "Di destpêka [karantînayê] de ez bêtir şok, tevlihev û matmayî mam. Û paşê her ku ew berdewam kir, ez bêtir bêzar bûm û xwe ewle, aram û bextewar hîs dikir... Xaltîka min bû, mîna ku wê min pir şa dikir û wê bi rastî li ser tiştê ku qewimî neaxivî... heke hûn li malê perwerde bibin wê hingê hûn bêtir tenê dimînin ji ber ku bi rastî hevalên we li dora we tune ne... Xwişk û birayên min tunebûn, lê xaltîka min jî li dibistanekê dixebitî, ji ber vê yekê ew ne ewqas mijûl bû, ji ber vê yekê wê min şa dikir û bi min re dilîst... Huner û karên destan, lîstina hin lîstikên rolê, çêkirina, ez ji bîr dikim ka navê wê çi ye, ew tiştên piçûk ên konê? Mîna ku di hundurê mala we de hûn kursiyan bikar tînin û hûn mîna qumaşek, şikeftek datînin." Dostên nêzîk di demên dijwar de piştgiriyê didin Chris, ê 16 salî, vegot ku çawa têkiliya wî bi diya wî re di dema qedexeyê de bandor bûye û di dawiyê de xirab bûye. Her çend ew kêfxweş bû ku bi bavê xwe re dijî jî, ev "teqîn" ji nişka ve û dijwar bû ku meriv pê re mijûl bibe û ew bêtir hişyar kir ku tenduristiya xwe ya derûnî biparêze. Wî vegot ku çawa lîstina bi hevalên xwe re û axaftina bi wan re her roj di dema qedexeyê de alîkariya wî kir ku ji tiştan derbas bibe û çawa bi demê re ew rehet bû ku bi koma hevaltiya xwe re li ser hestên xwe biaxive. "Em bi rastî her roj diaxivîn... heta ku ez dikarim bibîr bînim, koma hevalên min pênc kes bûn ku hemî pir nêzîkî hev in, û hûn dizanin, wê demê hevalên we yên hevbeş li dora wê hebûn, lê pênc ji me hemî bi berdewamî li ser komputerê bûn... ji ber vê yekê tiştek ji bo me neguherî, em hîn jî bi heman awayî diaxivîn ku em ê bi kesane biaxivin. Tenê ji ber ku em hemî ewqas nêzîk bûn, Covid qet nikaribû wê dostaniyê an wê girêdana ku me hebû bişkîne... [Pandemiyê] bê guman guherî, mîna ku ez çiqas hişyar bûm, mîna axaftina bi mirovan re li ser tenduristiya derûnî... awayê ku ez li ser hestên xwe, û dûv re jî bi hevalên xwe re û li ser hestên wan re diaxivîm guherî." |

Dîtina rêbazên piştgiriya başbûnêZarok û ciwanên ji her temenî tiştên ku wan di dema pandemiyê de li malê kirine, vegotin da ku bi zanebûn rehetiya xwe biparêzin û dema ku di tengasiyê de bûn xwe çêtir hîs bikin. Ji hewaya paqij û werzîşê bigire heya derbaskirina demê bi heywanan re, temaşekirin an xwendina tiştek revînê, şiyana kirina tiştek erênî an teselîker ji bo xwe di dema pandemiyê de ji bo zarok û ciwanan pir girîng bû. Hin kesan her wiha dîtin ku danîna rûtînek dikare ji wan re bibe alîkar ku ji bêzarî û bêhaliyê dûr bikevin.

| Dîtina rêbazên ku hûn xwe bextewar hîs bikin

Lou, 10 salî bû, di dema pandemiyê de bi dê û bav û xwişka xwe ya biçûk re dijiya. Dema ku wê dixwest tiştekî bike da ku di dema qedexeyê de xwe baştir hîs bike, wê hez dikir temaşekirina TV-yê, guhdarîkirina muzîkê û stranbêjiyê bike. Ji her tiştî zêdetir wê ji lidarxistina bernameyan bi xwişka xwe re hez dikir, ku ji hêla diya wê ve dihat teşwîqkirin ku pêşniyar dikir ku ew li malê wekî beşek ji ji nû ve afirandina rûtîna xwe ya dibistanê û çalakiyên piştî dibistanê berdewam bikin. Ev di dema qedexeyê de bû çalakiya wê ya bijare. "Ez û xwişka min ji bo dayikê mîna pêşandanên piçûk dikirin… me ji govendan hez dikir û me berê rûtîn çêdikir… Û diya min dixwest wê binirxîne û wê digot ku ew bi rastî baş bû. Û min bi rastî jê hez dikir… Min xwe pir aram û… bi rastî jî kêfxweş û heyecan hîs dikir. Ji ber ku min bi rastî tiştê ku min bi rastî kêfxweş dike dikir… [me] hevdu kêfxweş kir û alîkariya hev kir ku erênî bimînin û ne aciz bibin." Di pirtûkek hêja de teselî dîtin Ari, 18 salî, di dema pandemiyê de jiyaneke dijwar li malê derbas kir û di lîsteya benda piştgiriya tenduristiya derûnî de bû. Wan rave kir ku xwendina pirtûkek bijare ji bo wan çavkaniyek rehetiyê û revê bû û wêneyek vê yekê bi xwe re anî hevpeyvîna xwe. "Ew yek ji wan tiştan bû ku min di dema pandemiyê de dixwest bixwînim, min dixwest gelek bixwînim û her weha gelek guhdarî bikim, mîna pirtûkek dengî, ji ber ku ew ji bo min pir ronakbîr bû, û tiştek da min ku ez hişê xwe ji her tiştê ku diqewimî dûr bixim… şêwaza nivîsandinê bi rastî… lîrîk û helbestî bû… ew tiştek e ku ez pir hez dikim bixwînim, da ku min aram bike û min aram bike û tiştên wisa.” |

Kirina tiştekî bi xêrDi dema pandemiyê de - carinan bi awayekî nediyar - şiyana kirina tiştekî sûdmend alîkariya zarok û ciwanan kir ku bi bêzariyê re mijûl bibin, hişê xwe ji fikaran dûr bixin û di dema ku wekî "dema vala" ya qedexeyê dihat binavkirin de xwe bêtir motîve bikin. Ev yek pêşxistina jêhatîbûn û berjewendiyên heyî û kifşkirina hewes û jêhatîyên nû vedihewîne. Ev dikare encamên balkêş jî hebin ku dîtina tiştekî ku were kirin hobiyên nû îlham daye an jî rêwerzên akademîk an kariyerê yên pêşerojê vekiriye.

| Vedîtina hobiyeke neçaverêkirî ku bû sedema kariyerekê

Max, 18 salî, pandemiyê wekî demek stresdar dît, nemaze ji ber ku bavê wî ji hêla klînîkî ve xeternak bû û demek li nexweşxaneyê ma. Di dema qedexeyê de neçar ma ku dev ji werzîşên tîmê berde û ti hobiyên din tunebûn. Lê ji ber ku berber girtî bûn, ew îlham girt ku porê xwe bibire, dûv re dît ku ew bi rastî ji birîna porê kesên din kêfê digire û bi vî rengî rêyek nû ji bo pêşeroja xwe vekir. "Bi vî awayî ez ketim nav berberiyê... Min di dema qedexeyê de fêrî qutkirina porê xwe bûm... Min porê bavê xwe qut kir lê wî dixwest porê wî bi tevahî tazî be [ji ber vê yekê] min hemû sêwiran li ser serê wî çêdikirin û dû re min ew qut kirin... Di dema qedexeyê de bi rastî jî pêdivî bi qutkirina porê min hebû û eşkere ye ku berberên vekirî tunebûn, ji ber vê yekê min tenê makîneyek qirkirinê siparîş kir û min dest bi pratîkê li ser xwe kir... Min bi rastî jê kêf girt... Ez hîs dikim ku bi Covidê re min fêrî hobiyek bû... [ji wê demê ve] Min asta 2-an li zanîngeha berberiyê qedand û min azmûnên xwe derbas kirin... [Bêyî Covidê] niha ew sertîfîkaya min tunebû û ez bi rastî ji berberiyê kêfxweş dibim, ez niha tenê li stajyeriyek di firoşgehekê de digerim." Hest bi serbilindî û kêfxweşiyê ji bo bidestxistina armancekê Elliott, 12 salî, ji aliyê Kapîtan Tom ve îlham girt ku xwe bixe ber pirsekê û hinek pere ji bo xêrxwaziyê berhev bike. Bi piştgiriya diya xwe, wî biryar da ku armanc bike ku 100 dor li dora blokê bimeşe, ku paşê bû 200. Cîran serê xwe derdixistin da ku wî bibînin û ev bû hewldanek rastîn a berhevkirina pereyan ji bo civakê: "Di dema ku me saetek rojane hebû de, min ew dor li dora bloka xwe çend dor derbas dikir heya ku ez gihîştim sed lîreyan, û me du hezar lîre berhev kir... Ew pir kêfxweş bû, û dûv re di dawiyê de dema ku me şahiya mezin kir, ew tenê bîranînek pir baş bû ji bo min û ew alîkariya min dike ku ez li ser aliyên baş ên Covid-ê bifikirin û kêmtir li ser aliyên xirab... [Me pere berhev kir] ji bo NHS-ê, ez difikirim, lêkolîna li ser... mîna derzîyan, ez nizanim navê wê çi ye... vakslêdanan. Ji ber vê yekê ew çû NHS-ê, lêkolîna Covid-ê... erê [min xwe serbilind hîs kir], ew tiştek pir kêfxweş bû ku min di dema qedexeyê de mijûl kir." |

Kapasîteya berdewamiya fêrbûnêZarok û ciwanan vegotin ku ger ew di dema pandemiyê de karibin fêrbûnê bidomînin, tevî astengiyên berfireh ên perwerdehiyê û zehmetiyên fêrbûna ji dûr ve, ev yek hişt ku ew xwe erênî hîs bikin û ku ew dikarin di dibistan, kar û jiyanê de bigihîjin tiştê ku ew dixwazin. Ev dikare ji ber wergirtina alîkariya ku ji dêûbavan an karmendên mamosteyan hewce dikir, şiyana çûyîna dibistanê dema ku yên din li malê bûn (ji bo zarokên xebatkarên sereke), an jî kêfa nêzîkatiyek nermtir û serbixwe ya fêrbûnê be. Fêrbûna ji dûr ve ya serketî her weha bi gihîştina amûrên guncaw ji bo fêrbûnê û di hin rewşan de bi şopandina rûtînek li malê ve jî hate piştgirî kirin.

| Bi rêbazek fêrbûna serbixwe serfirazî

Jordan, 13 salî, ji dibistanê bêtir ji fêrbûna li malê û hînkirina xwe bi xwe kêf digirt, ku ev yek baweriya wê bi şiyanên wê zêde kir û xwest ku ew bibe mamoste. Wê hîs kir ku dikare ji malbatê alîkariyê bixwaze (yek ji dê û bavê wê li malê dixebitî û yê din jî bêkar bû), xwe ewle hîs dikir, û heke pêwîst bike, vebijarkên wê hebûn ku bi e-name an têlefonê bi mamosteyan re têkilî daynin. Wê heman rûtîna ku li dibistanê dikir şopand lê ji bo ku bi tena serê xwe peywirên xwe biqedîne li ser lînkan dixist. "Hûn dikarin li ser lînka Matematîkê an lînka Îngilîzî an wê lînka zanistê an jî hwd. bikirtînin. Û hûn dikarin, û dûv re hûn tenê li ser wê dersê bikirtînin û peywirê ku ji bo wê dersê hatibû danîn bikin... Di demekê de diya min dixwest ez bişînim dibistanê lê min bi rastî nexwest biçim ji ber ku ez di fêrbûna malê de baş bûm û ez jê kêf digirtim... Min ew wekî rojek dibistanê dikir. Mînak, min hez dikir, nizanim, ez dixwazim gava ez mezin bibim mamosteyek bim... Ji ber vê yekê ez dixwazim, hez dikim tenê, mîna, plansazkirina wê bikim, û carinan ez xwe wekî mamoste nîşan didim û, mîna, hîn dikim, mîna, pêlîstokên xwe yên şîrîn... hûn dikarin her gav, mîna, e-nameyê ji [mamosteyan] re bişînin an jî telefonê ji wan re bikin û, mîna, dema ku min karê xwe dikir, carinan ez, mîna, wêneyan dişînim û nîşanî wan didim, û dûv re ew ê bibêjin, 'ew bi rastî baş e'." |

Girîng e ku were zanîn ku ev hemû faktor bi derbaskirina demê li ser înternetê ve girêdayî ne - ji têkiliya bi hevalan bigire heya lîstina lîstikan û fêrbûna tiştên nû ji dersên serhêl. Tevî zehmetiyên ku hin kes di rêvebirina mîqdara dema ku ew li ser înternetê derbas dikirin de û xetera rûbirûbûna zirara serhêl, li ser înternetê mayîn dikare di dema pandemiyê de ji bo zarok û ciwanan çavkaniyek hêja ya têkiliya civakî, rehetiyê, revînê û îlhamê be.

3. Çawa jiyan di dema pandemiyê de bandor bû

3.1 Mal û malbat

Têgihiştinî

Ev beş ezmûnên jiyana mal û malbatê di dema pandemiyê de vedikole, rêzeya dijwarî û berpirsiyariyên li malê yên ku pandemiyê ji bo hin zarok û ciwanan bi taybetî dijwar kir û beşdariya têkiliyên piştgirî û rûtînên malbatê di alîkariya zarok û ciwanan de ji bo li hember vê yekê bisekinin, destnîşan dike. Her wiha em vedikolin ka zarok û ciwanan çawa hîs kirine ku ew ji ber qutbûna têkiliya bi endamên malbatê yên ku di dema pandemiyê de bi wan re nejiyane bandor bûne.

Kurteya Beşê |

|

| Aliyên piştgiriya jiyana malbatê

Zehmetiyên li malê Astengkirina têkiliya malbatê Gotinên dawî |

|

Aliyên piştgiriya jiyana malbatê

Ji ber ku di dema qedexeya derketina derve de gelek dem li malê derbas dikirin, girîng bû ku di hawîrdorek ewle û piştgir de bimînin. Zarok û ciwanan vegotin ku çawa girêdana bi malbatê re û bi hev re çalakî, rûtîn û pîrozbahiyan ezmûna wan a pandemiyê xweştir an hêsantir kiriye ku meriv pê re mijûl bibe. Balkêş e ku meriv bibîne ku zarok û ciwanan her gav dê û bavên xwe ji bo danîna van çalakiyan û çêkirina hin kêliyan ji bîrnekirî pesnê nedidan, lê eşkere ye ku hin ji wan ji hewildanên mezinan sûd wergirtine da ku jiyana li malê erênîtir bikin.

Têkiliyên malbatî

Derbaskirina bêtir dem bi hev re wekî malbatek ji bo zarok û ciwanan di hemû temenan de aliyek girîng ê ezmûna pandemiyê bû. Wekî ku li jor hate vegotin, ji bo hin kesan, sînordarkirina li malê bi hev re bû sedema tengezariyan, an jî tengezariyên li cihê ku berê hebûn zêde kir. Lêbelê, vegotinên jiyana malbatê ezmûnên erênî jî dihewîne, carinan di nav dijwarîyan de. Di hin rewşan de, hate gotin ku pandemiyê endamên malbatê nêzîkî hev kir û têkiliyan xurt kir. Ev girîng e ji ber rola ku têkiliyên piştgirî di alîkariya zarok û ciwanan de lîstin da ku di dema pandemiyê de li hember wan bisekinin.

| "Niha ez dizanim ku girîng e ku meriv bi malbata xwe re têkiliyek çêbike… [di dema qedexeyê de] em dibe ku pir zûtir, bêtir û ji ber ku em bi hev re bêtir çalakî û tiştan dikirin, pêwendiya me çêbû." (9 salî)

"Min ji hebûna li malê û li dora dê, bav û xwişk û birayên xwe hez dikir. Min ew xweş dît." (16 salî) "Ez difikirim ku wekî malbat em hemî nêzîk bûn [berî pandemiyê], lê em niha hîn nêzîktir in; Ez difikirim ku divê em ji bo vê yekê spasiya qedexeya derketina derve bikin." (16 salî) |

Hin ji kesên ku di dawiya xortaniya xwe an jî di bîst saliya xwe de bi wan re hevpeyvîn hatine kirin, niha diyar dikin ku ew ji bo hevaltiya malbata xwe spasdar in û ew demek taybet bi hev re bû.

| "Ez difikirim ku bê guman ev yek hişt ku ez bêtir li malê bimînim û bi dê û bavê xwe re li malê wext derbas bikim. Tenê tiştên hêsan bikim. Ne her tim mijûl bim." (16 salî)

"Ez dibe ku di wê qonaxê re derbas dibûm mîna S2"4 cihê ku ez naxwazim bi malbata xwe re derkevim. Lê ji ber ku bi rastî pir bijarte tune ye, ez ê bi wan re biçim meşê û tiştên wisa. Ez difikirim erê, ev yek me wekî malbatek pir nêzîktir kir.” (17 salî) "Bê guman min ji her carê bêtir bi diya xwe re girêdanek çêkir, ji ber ku ez hinekî neçar bûm, ji ber vê yekê ew tiştek baş bû." (18 salî) "Bi xwişk û diya min re, ew bêtir wekî hincetek bû ku em bi hev re bêtir tiştan bikin û tenê li baxçê rûnin û bi saetan biaxivin ji ber ku tenê ev bû ku me dikarîbû bikin... bê guman ev yek têkiliyên me xurt kir ji ber ku ez dîsa hîs dikim ku em [bi gelemperî] wê yekê wekî tiştekî asayî dibînin ku em her roj wan dibînin lê bi rastî jî em bi hev re demek bi kalîte derbas nakin." (21 salî) "Ez difikirim ku em ê bê guman gelek caran bi hev re şîvê bixwin. Ji ber ku ev tiştek e ku me qet nekiriye ji bilî dema ku ez û birayê min pir ciwan bûn... Ji ber vê yekê pir xweş bû ku em çar kes bi hev re wext derbas bikin ji ber ku ew demek dirêj e ku ne wisa bû ji ber ku ez wê demê li zanîngehê bûm û dûv re jî berî ku ez biçim zanîngehê birayê min li zanîngehê bû. Ji ber vê yekê demek dirêj bû ku em hemî bi hev re nebûn." (22 salî) |

- 4 S2 sala duyemîn a perwerdehiya navîn li Skotlandê ye.

Tewra li cihên ku di navbera xwişk û birayan de nakokî hebû jî, hin zarok û ciwanan bi bîr xistin ku ew hîn jî ji derbaskirina bêtir dem bi hev re û dîtina rêyan ji bo şerkirina bêzariyê kêfxweş dibûn.

| "Ez difikirim ku ew bi rastî ji bo me pir baş bû ji ber ku her çend me dest bi nîqaşan kir jî, ew hema hema me bi hev ve girê da ji ber ku em tiştan dikirin." (12 salî)

"Ez û xwişka min - em bi rastî ji satrancê hez kirin. Em ewqas bêzar bûn. Me texteyek satrancê hebû û me dest bi lîstina lîstik bi lîstik bi lîstik kir." (15 salî) "Me dest bi zêdexwarina tiştan kir, lîstikan temam kirin. Û bi rastî, dîsa, min hîs kir ku [birayê min] êdî hevalê min bû." (18 salî) "Ez û xwişka min a mezin, me dest pê kir ku em hinekî bêtir nêzîkî hev bibin û… em bi hev re xweş bin. Ji ber ku em her gav nîqaş dikirin lê gava em li malê bûn me fêm kir… divê em bi hev re biaxivin û lîstikan bilîzin." (18 salî) "Xwişk û bira baş in û ez naxwazim bêyî wan vê yekê derbas bikim… kesek li malê heye ku hûn dikarin pê re kêf bikin û kêfê bikin." (16 salî) |

Hinek kes dîtina bêtir dêûbavên ku ji malê dixebitin an jî ji kar hatine dûrxistin wekî aliyek erênî ya qedexeya derketina derve (ku zarokên karkerên sereke tecrûbe nekirine) behs kirin.

| ""Di dema qedexeya derketina derve de, ez û bavê min ê ku gelek li dûr dixebitî, me gelek dem bi hev re derbas kirin, ji ber vê yekê em di wê demê de hinekî nêzîktir bûn, ji ber ku, eşkere ye ku em tevahiya rojê bi hev re derbas dikirin." (14 salî)

"[Bavê min li malê bû] bi awayekî derfetek da min ku ez bi bavê xwe re têkiliyek çêbikim an jî têkiliyek xurttir çêbikim." (18 salî) "Bi gelemperî, em pirtir dem bi hev re derbas dikirin ji ber ku dê û bav pir caran li ser kar bûn, ji ber vê yekê pir xweş bû ku her kes her dem li wir bû... Em her roj diçûn meşê û lîstikên sifrê û tiştên wisa dilîst. Û wê demê her tim bernameyeke televîzyonê hebû ku em temaşe bikin." (16 salî) "Dê û bavê te, eger ew karkerên girîng ên mîna yên min bûna, ew her tim karên xwe dikirin. Bi rastî pir wext tunebû ku em bi hev re derbas bikin. Me şîv û taştê û firavîn derbas kir lê tenê ewqas. Ez rojekê li wir rûniştim tînim bîra xwe… Min hemû karê xwe yê dibistanê qedandibû û ez li wir rûniştibûm û top diavêtim û dîsa û dîsa digirtim heta ku diya min hat malê." (12 salî) |

Çalakî û rûtînên malbatê

Zarok û ciwan, lê bi taybetî ew kesên ku di dema pandemiyê de temenê dibistana seretayî bûn, çalakiyên malbatî wekî bîranînek sereke ya pandemiyê bi bîr anîn. Ev çalakî li seranserê astên dahatê hatin jiyîn û di nav wan de lîstina lîstikên sifrê, şevên fîlman, huner û karên destan, çêkirina xwarinê, nanpêjandin, û werzîşên Joe Wicks û her weha xwarina bi hev re hebûn. Meşên wekî malbat jî ji bo hin kesan bîranînek xurt bû. Ev yek di nav xwe de gerandina li dora taxê ji bo temaşekirina wêneyên kevanên rengîn ên ku mirovan di dema pandemiyê de wekî sembola hêvî û piştgiriyê ji bo Xizmeta Tenduristiyê ya Neteweyî (NHS) li pencereyên xwe daliqandin, digirt.

| "Me gelek tiştên cuda kirin û me wekî Foam Clay bikar anî da ku li ser van wekî gil û tiştan deynim û şekil û tiştên xwe çêbikim û carinan em piştî nîvro firin an xwarin çêdikirin û gelek huner û karên destan û tiştên wisa hebûn.” (14 salî)

"Ez difikirim wekî 'oh, bîranînên min ên xweş hene'... yek ji wan ên ku nû hatin bîra min derbarê teşwîqeke baş a ji hêla diya min ve bû, mîna ku me werzîşa werzîşê ya serhêl dikir... Joe Wicks... Ez li ser dekê tînim bîra xwe ku diya min digot 'were, tu dikarî bikî, were'." (11 salî) "Carinan di dema Covidê de em vê yekê dikirin ku her hefte, ev kes xwarina ku dixwaze hildibijêre û dû re bi dê an bavê min re çêdike... û dû re em welatekî hildibijêrin, hûn dizanin, mîna xwişka min Îtalya kir... [Hin şevan] her kes fîlmek hildibijêre. Me ew dixist nav şapikekê û dû re me yek hilbijart." (11 salî) "Çend caran me sofaya di baxçeyê xwe yê mîna xwe de digerand û me TV anî û danî ser vê kursiyê û dû re me şevek fîlmê li derve temaşe dikir." (12 salî) "Em hemû diçûn meşê, ev tiştê ku me wek malbat dikir bû. Em bi rastî jî mîna sê saetan dimeşiyan, belkî ev tiştê ku me herî zêde dikir bû... me gelek fîlm temaşe dikir, Joe Wicks temaşe dikir... Me bi hev re xwarin dixwar û bi gelemperî em nedixwarin... Me gelek caran hevdu didît û bê guman gelek dem bi hev re derbas dikir." (14 salî) "Em her tim diçûn meşên rengîn û hemû rengînên kevanê didîtin û em her tim dixwestin her roj rengînên nû çêbikin û tevahiya pencereya xwe tijî bikin. Ji ber ku li mala me ya kevin, pencereyeke mezin li pêşiyê hebû û me ew bi hemû rengînên kevanê tijî dikir, dû re temaşe dikir ka mirov çawa derbas dibin û wan dibînin." (11 salî) |

Zarokên mezintir û ciwanan jî çalakiyên malbatî yên wekî meş, temaşekirina fîlman û xwarina xwarinê bi malbatê re bi bîr anîn. Lêbelê, ew jî bi awayekî cuda wext derbas dikirin, nemaze heke ekranên wan ên taybet hebin. Hin kesan hîs kirin ku têkiliyên wan bi endamên malbatê re bi rastî pir sînordar in ji ber ku ew hemî bi hev re li malê bûn.

| "Min hest dikir ku em hemû tenê karê xwe dikin, her çend ez, birayê min û bavê min di bin yek banî de bûn. Bernameyên me hemûyan cuda bûn. Bi rastî me tenê ji bo şîvê hevdu didît.” (20 salî)

"Di dema pandemiyê de, ji bilî ku bi rastî em ji bo tiştan daketin jêr, me zêde bi hev re têkilî nedan." (13 salî) |

Ji bo malbatên xwedî baxçe, ev der carinan di dema qedexeya yekem a derketina derve de dibû navenda çalakiyên malbatî. Çalakiyên li derve yên ku ji hêla zarok û ciwanan ve hatine vegotin ev bûn: lîstin û werzîş, çandina fêkî û sebzeyên xwe, rojgirtin û xwarina li derve bi malbatên xwe re. Hin kesan teqdîr kirin ku ew bi şens in ku ev cih li derve heye.

| "Dayika min ji me re stûnek netbolê kirî… tenê ji ber ku ew tiştek bû ku em dikarin li baxçeyê hebe. Ew tiştek bû ku [ez û xwişka min] derxin derve. Û ez difikirim ku ew bû, mîna ku min bi rastî jê kêf girt. Û min got, ev bi rastî jî kêfxweş e… Ez bi rastî jî bextewar bûm ku baxçe hebû.” (13 salî)

"Dema ku Covid li ba me tunebû, me li baxçeyê xwe barbekû çêdikir û her wiha me li baxçeyê xwe krîket, futbol û basketbol dilîst." (10 salî) "Ez bi şens bûm, xaniyek min a xweşik bi baxçeyek hebû, ku bi zeviyan dorpêçkirî bû, ku ez dikarim bigihîjimê." (18 salî) |

Divê bê zanîn ku di nav kesên ku hevpeyvîn pê re hatiye kirin de zarok û ciwanên ku gihîştina wan bi baxçeyekî tunebû jî hebûn, yên ku bi gelemperî li hawîrdorek bajarî an derbajarî û di malbatek bi dahata kêm de dijiyan. Di hin rewşan de, nebûna baxçeyekî wekî dijwartirkirina pandemiyê hate wesifandin. Mînakî, zarokekî behsa wê yekê kir ku dema ku diya wê xwe sûcdar hîs kir ku ew "di apartmanekê de asê mane" koçî ba dapîr û bapîrên xwe kir da ku bigihîje baxçeyekî, ew çûye wir. Lêbelê, ev yek ji hêla kesên bê baxçe ve bi piranî nehat behs kirin û ew meyla wan hebû ku li ser windakirina derfetan neaxivin - her çend wan aliyên erênî yên ku ji hêla kesên xwedî baxçeyan ve hatine vegotin nejiyan.

| "Em li apartmanek pir bilind dijiyan… pir dijwar bû ji ber ku hewaya me ya teze tune bû. Ger me hewaya teze bixwesta, me serê xwe ji pencereyê derdixist û tenê bêhna xwe dida… ne xweş bû… baxçe tune bû.” (13 salî)

"Dibe ku min bixwesta baxçeyekî min hebûya lê bi rastî tune bû - ez nafikirim ku ew bi rastî pir bandor li me kiribe." (21 salî) |

Di dawiyê de, çîrokan destnîşan kirin ku çawa hin zarokan ji hewildanên ku ji bo pîrozkirina bûyerên taybetî li malê têne kirin, dema ku qedexeyên pandemiyê rê li ber derketina wan girt, sûd wergirtine. Hin zarok û ciwanan bi bîr anîn ku wan ji rêbazên alternatîf ên pîrozbahiyê wekî malbat kêf girtiye û van rêbazan teqdîr kirine.

| "Ji ber ku em nekarîn wekî roja rojbûna bavê min derkevin derve, me ew wekî roja Meksîkî çêkir ku me ew wekî ponço û şapikek stend û ji bo rojbûna wî xwarina Meksîkî çêkir.” (12 salî)

"[Di roja jidayikbûna min de bavê min] li ser eywana me dîskoyek çêkir û pir bi deng bû, ji ber vê yekê hemû kolan li malên xwe direqisîn û tiştên wisa... Lê pir xweş bû, ji ber ku min dîsa jî hevalên xwe dît [yên ku hatin binê baxçê] lê ew tenê hinekî dûr bûn." (12 salî) "Ez bi gelemperî ji bo rojbûna xwe şahiyekê li dar dixim, lê wê salê, mîna diya min, em çûn meşê û gelek otomobîl li dawiya rê bûn û hemû heval û malbata min digotin rojbûna te pîroz be... Bi rastî jî xweş bû. Ji ber ku min mehek bû kes nedîtibû û ez pir kêfxweş bûm ku min her kes dît." (14 salî) "Em bi rastî nekarîn malbata berfireh pir caran bibînin... Û pîrozbahiyên mîna Cejnê hebûn ku em ji ber tedbîrên ewlehiyê nekarîn bi qasî pêwîst û bi rêkûpêk pîroz bikin. Ji ber vê yekê me xwarin ji malên hev re şand." (15 salî) |

Zehmetiyên li malê

Li jêr em bi hûrgilî li ser cûrbecûr pirsgirêkên li malê ku di dema pandemiyê de bandor li hin zarok û ciwanan kirine, rave dikin. Em aloziyên malbatî û ka ev çawa dikarin ji ber dijwarîya zêde ya jiyana di xanîyên qerebalix de zêde bibin, vedikolin.5 Her wiha em lêkolîn dikin ka zarok û ciwanan çawa hîs kirine ku gava kesek di malê de bi Covid-19 ket, ew bandor bûne û ji bo kesên ku berpirsiyariyên lênêrînê hene, çi dijwarî li malê hene.

- 5 Pênaseya xanîyên qerebalix ev e: "malbatek ku ji bo dûrketina ji parvekirinê, li gorî temen, zayend û têkiliya endamên malê, ji ya ku pêwîst e kêmtir odeyên razanê hene. Bo nimûne, ji bo van kesan pêdivî bi odeyek razanê ya cuda heye: cotek zewicî an jî bi hev re dijîn; kesek 21 salî an jî mezintir; 2 zarokên ji heman zayendê yên 10 heta 20 salî; 2 zarokên ji her zayendê yên di bin 10 salî de." Ji kerema xwe binêre: Malên qerebalix - GOV.UK Agahdarî û hejmarên etnîsîteyê

Rageşiyên malbatî

Heta ji bo malbatên ku baş li hev dikirin jî, di dema qedexeya derketina derve de bi hev re asê man wekî çavkaniyek aloziyê dihat bibîranîn. Zarok û ciwanan hestên xwe yên "asêmayî", "klaustrofobîk" û "li ser hev" vegotin. Ev bi taybetî ji bo kesên ku xwişk û birayên wan hebûn rast bû, û heta li cihên ku ew ji hevaltiya hev kêf digirtin jî, nêzîkbûna laşî ya domdar dikaribû bibe sedema nîqaşan.

| "Belê, min ji dema ku min bi wan re derbas kir re qîmet da. Lê ew pir stresdar bû." (17 salî)

"Her dem bi xwişk û birayê xwe re jiya, mîna ku li yek cîhekî asê bimînî, bê guman ev yek bû sedema gelek, mîna, gelek şerên ji berê zêdetir." (17 salî) "[Ez û xwişka min] pir li hevdu diketin. Mînak, me qet li hev nedikir. Niha hinekî çêtir e lê tevahiya jiyana me me li hev nedikir. Ji ber vê yekê, dema ku em her dem bi hev re bûn, mîna li malê, hinekî zêde bû." (19 salî) "Hûn dikarin bi rastî jî bi wan re bibin hevalên herî baş, alozî zêde dibe, û hin rojan ew tenê diqede û tevahiya malê ji hev nefret dike." (16 salî) "Li malê hinekî stresdartir bû ji ber ku xwişka min a biçûk wê demê hinekî bêexlaq bû, mîna ku li dibistanê nebaş tevdigeriya û tiştên wisa. Û paşê wê ew anî malê, mîna ku di dema qedexeya derketina derve de destûr nedida wê ku here dibistanê an derkeve û tiştên wisa. Ji ber vê yekê, ew tenê di malê de derdixist û tiştên wekî nîqaş an qîrîn û tenê paşguh dikir mîna ku jê re digotin û tiştên wisa... ev yek diya min stres dikir, û ew stres dikir ji ber ku ew jî nikaribû tiştekî bike, û dû re xwişka min a din... meriv dikare bibêje ku ew wê aciz dike, lê ew jî tiştek nedigot. Ji ber vê yekê, ez difikirim ku ev tenê malê bi rastî xemgîn kir, lê her kes tenê mîna ku ew li hev derdiketin û dûv re hewl didan ku ji hev dûr bisekinin." (22 salî) "Ez difikirim ku mirov ji bo demek dirêj pir zêde di qada mirovan de bûn." (21 salî) |

Hin ji kesên ku hevpeyvîn pê re hat kirin hîs kirin ku nebûna cîh li malê dibe ku tiştan ji bo wan dijwartir kiribe, nemaze li cihên ku xwişk û bira odeyên razanê parve dikirin an jî cîh ji bo lîstin, temamkirina karên dibistanê, an jî bi tena serê xwe derbaskirina demê kêm bû. Kesên ku di dema pandemiyê de di xortaniya xwe de bûn, bi taybetî li ser nebûna cîhê xwe yê taybet hest bi tundî kirin.

| "Me piraniya demê bi hev re derbas dikir, û em hev aciz dikirin.” (12 salî)

"Em hemû di bin heman xanî de bûn, xaniyek me ya mezin û mezin tunebû, ji ber vê yekê em tenê hewl didan ku bixebitin, zanîngehê bikin, dersên dibistanê ji malê bikin, û eşkere ye ku her du jî li ser Zoomê bûn, û her du jî digotin, 'devê xwe bigire!'" (21 salî) "Ez difikirim ku me gelektir gengeşî kir û em tenê ji ber ku nêzîkî hev bûn, me nîqaş kir, em tenê digotin, oh, carinan pêdivî bi cîhê xwe heye." (19 salî) "Cih tunebû ku meriv lê rûne, mînakî, heke kesek te aciz bikira, te hîn jî dikarî bêhna wan ji odeya din bibihîsta." (21 salî) "Gelek kesan digot ku wan pir wext hebû ku [di dema qedexeya derketina derve de] bifikirin. Lê ji ber ku zarokên biçûk li mala min hebûn, wextê min kêmtir bû ji ber ku ez her gav digot, min qet bêdengî nedîtibû ku di serê xwe de bifikirim ji ber ku her gav kesek diaxivî." (18 salî) |

Di van şert û mercan de, dîtina rêyan ji bo çêkirina cihekî girîng bû. Hin zarok û ciwanan vegotin ku ew bi fîzîkî di cihê hev de bûn, lê bi rêya înternetê, an jî bi karanîna guhguhkên deng-bêbandorker ji bo nîşandana ku ew dixwazin bi tenê bimînin û bi wan re neaxivin, hin cudahî çêkirin.

| "Ez bawer nakim ku min ewqas bi dê û bavê xwe re axivî ji ber ku em hemû di heman malê de bûn, xaniyek piçûk, lê her kes di rewşek xirab de bû… [ez û dayika min] hema hema bi hev re nediaxivîn, tenê ji bo ku xwarin û tiştên wisa bînin ji min re, ji bo ku li ser dibistanê biaxivin, lê ji ber ku ez bi piranî bi têlefonên serhêl re mijûl dibûm û mîna ku bi iPad-a xwe ve girêdayî bûm, min bi wê re neaxivî.” (18 salî)

"Me gelek dem di heman odeyê de bi hev re derbas kiribû lê me bi rastî pir bi hev re neaxivî ji ber ku em herdu jî serhêl bûn, mîna ku di nav bilbilên xwe yên piçûk de bûn." (20 salî) |

Hin zarok û ciwan, bi taybetî yên ku di dema pandemiyê de temenê dibistana navîn bûn, hîs kirin ku ew di dema qedexeyê de bêtir bi dêûbavan re nîqaş dikirin. Ev carinan ji ber ku dêûbav rêzik û sînordarkirin li ser wan danîne, mînakî destpêkirina rotasyonan ji bo karanîna konsolên lîstikê ji hêla xwişk û birayan ve an sînordarkirina dema ku li ser ekranan derbas dibe, pêk dihat. Nîqaş her wiha li ser rûtîn û çiqas karê dibistanê dihat kirin bûn. Zarok û ciwanan her wiha nîqaşên ku dêûbav sînordarkirin danîn ser kesên ku ew dikarin ji malê bibînin an jî gelo ew dikarin derkevin derve, her çend sînordarkirinên neteweyî destûr bidin wan ku wiya bikin jî bi bîr anîn.

| "Dibe ku ez ji [dê û bavê xwe] bêtir hêrs bûm ji ber ku nehiştin ez hin tiştan bikim… Ez pir bêzar bûm… wan nehiştin ez hin tiştên ku min dixwest bikim bikim… wek mînak Xboxek bistînim, ku niha li cem min heye lê wê demê min nekarî ji ber ku wan nehiştin ez bistînim.” (13 salî)

"Me gelek nîqaş kir, bi taybetî tenê ez û diya min li ser dibistanê û rabûna ji nivînan." (19 salî) "Ew yek bû sedema gelek, wekî, gelek pevçûnên zêdetir bi diya min re jî ji ber ku em ê pirtir dem bi hev re derbas bikin. Mînak, bi kêmanî berî ku ew bêhnvedanek bistîne û ez jî bêhnvedanek bistînim dema ku ez li dibistanê bûm an li derve bûm an jî çi dikir. Lê, wekî, em pir bêtir li hemberî hev bûn… Ez pir bêserûber, pir bêserûber bûm, tiştan li her derê dihiştim û ev, wekî, bi rastî jî di bin çermê diya min de bû… Ez her tim bi diya xwe re li ser tiştên pir bêaqil şer dikir." (18 salî) "Niha [ez û diya min] baş in, lê berî û di dema pandemiyê de her tim wekî, xitim, xitim, xitim, xitim hebû." (21 salî) "Ez tînim bîra xwe ku diya min pir aciz bû ji ber ku di kêliya yekem de ew li ser pandemiyê pir paranoyak bû, ez difikirim û ez û bavê min em derketin meşê… û wê got, 'ey Xwedayê min, tu çawa dikarî wisa bikî'?" (21 salî) |

Hin zarok û ciwan ji aloziyên di navbera mezinên di malbata xwe de haydar bûn. Ciwanên di wê demê de di temenê xortaniyê de, bêtir îhtîmal bû ku ferq bikin ka pandemiyê di têkiliya dê û bavên wan de alozî çêkiriye. Ev yek bi windakirina kar, fikarên darayî û pirsgirêkên heyî yên di têkiliyê de, û her weha bi xebata ji malê û neçarbûna parvekirina cîh bi malbatê re ve girêdayî bû. Ev dikare ji bo zarok û ciwanên têkildar bibe sedema fikar, stres û nezelaliyê.

| "[Atmosfera malê] pir aloz bû. Pir, pir aloz… ji ber ku kesî nedixwest bi hev re biaxive… ji ber ku [diya min û hevjîna wê] têkiliyek pir xirab hebû, bi her tiştî stresdar bûn û me qet bi hev re neaxivî." (14 salî) |

Ev lêkolîn her wiha ezmûnên tengezariya li malê ji kesên ku di rewşên taybetî de bûn tomar kir. Hin ciwanan zehmetiyên ku di dema pandemiyê de rastî wan hatine parve kirin, ji ber ku malbatên wan piştgirî nedan wan ku ew bibin xwedî... LGBTQ+ (lezbiyen, gey, biseksuel, transgender, queer û yên din). Ev ji ezmûnên nekarîna xwe îfade bikin an jî bi eşkereyî bi malbatên xwe re biaxivin bigire heya dijminatiya malbata wan li hember wan diguhere. Ev ciwan bi taybetî ji ber qedexeya derketina derve bandor bûn ji ber ku ew nekarîn ji hawîrdora mala xwe birevin û nekarîn bi tevahî bibin xwe an jî xwe bi awayê ku dixwestin îfade bikin.

| "Dema ez derketim ba [dayika xwe], bi rastî jîngehek dijminane bû ji bo rûniştinê.” (20 salî)

"Min dixwest li dibistanê xwe bêtir îfade bikim ji ber ku ez ji dê û bavê xwe dûr bûm, yên ku vê yekê qebûl nedikirin, ji ber vê yekê li dibistanê ez nêzîkî heşt saetan ji wan dûr mam da ku ez bikaribim xwe bêtir îfade bikim, lê ji ber ku ez her dem bi wan re bûm, ev yek bi rastî rê li ber wê yekê vekir ku ez çawa bikaribim xwe îfade bikim." (19 salî) "Rewşa malbata min ne pir baş bû… ji ber vê yekê li mala min kes tunebû ku ez pê re biaxivim… Ez tenê di odeya xwe de asê mam mîna malbatek ku min bi rastî jê hez nedikir, tenê salekê bêyî ku ez bi tu kesî re biaxivim, û vê yekê tenduristiya min a derûnî jî têk bir… pandemiyê hişt ku ez bi rastî hay ji wê yekê heb ku ez bi rastî çiqas ji malbata xwe û cihê ku ez wê demê lê dijîm hez nakim." (19 salî) "Hevalên min ên ku min li zanîngehê nas dikirin, ew digotin, baş bûn, lê li malê ne xweş bû, hûn dizanin ez çi dibêjim... şaş fam nekin, mîna ku li malê baş e, lê mîna ku hinekî astengker e, hûn dizanin ez çi dibêjim ji ber ku dîsa, an bi taybetî bi nasnameyê re, ku ji paşxaneyek olî û muhafezekar tê, ew bi rastî li hev nayên, ji ber vê yekê ez tenê neçar im ku wê derî bigirim heya ku ez bikaribim vegerim zanîngehê û dîsa vekim." (22 salî) |

Herwiha vê lêkolînê ezmûnên zarok û ciwanan jî lêkolîn kir. di rewşek lênêrînê de di dema pandemiyê de, yên ku carinan behsa tengezariyên ku bi kesên ku ew bi wan re dijiyan re dikirin kirin. Zarokekî diyar kir ku ew li malê bi malbata xwe ya xwedîkirî re asê maye û hîs kiriye ku ew nikare ji wê jîngehê bireve, nemaze ji ber ku di destpêka qedexeyê de telefona wî tunebû ku bi yên din re têkilî dayne.

| "Wê demê telefona min tunebû, ji ber vê yekê danûstandina bi hevalan re pir dijwar bû… Ez difikirim ku [pandemiyê] pir mezin û bandorker li ser min kir ji ber ku bi rastî nekarîbûm bi mirovan re biaxivim an jî danûstandinê bikim… Ez nekarîbûm biçim dibistanê, ji ber vê yekê erê, ez pir di malê de asê mabûm… Rageşî her diçû zêde dibû û asêbûna bi [xwedîkarên xwe yên xwedîkirî] re rewşê pir xirabtir dikir ji ber ku ez bi rastî nekarîbûm ji wan dûr bisekinim an çi dibe bila bibe. Ji ber vê yekê tenê her dem li wir bûn ne ya herî baş bû.” (17 salî) |

Hin ciwanên ku di dema pandemiyê de li malên zarokan bûn û hevpeyvîn pê re hat kirin, her wiha vegotin ku di dema qedexeya derketina derve de bi kesên din ên ku bi wan re dijiyan re tengezarî dîtine, nemaze ji ber ku her kes ji rewşê bêzar û dilşikestî bû. Ciwanek jî rave kir ku rêziknameyên pandemiyê çiqas bi tundî li mala wê dihatin sepandin û hestên wê yên dilşikestî hebûn ji ber ku ew qet nikarîbû ji qadê derkeve.

| "[Di wê malê de] gelek nakokiyên navkesane jî hebûn. Û ez difikirim ku beşek mezin ji vê yekê ji ber Covidê ye. Mirov tiştek nedikarîn bikin, ji ber vê yekê tenê gelek bêzarî diafirand, ku dûv re li ser mirovên din jî dihat nîşandan. Û dûv re hewl didin ku dest bi tiştên ku tenê dema wan tijî dikin bikin ji ber ku tiştek çêtir ji wan re tunebû ku bikin." (19 salî)

"[Ez] gelek caran bêzar bûm. Baş bû lê wê demê em, wek mînak, heta mala ku ez lê dijiyam, apartmana bi zarokan re, bi keçên din re, wek mînak, em bêzar dibûn û wê demê me dest pê dikir, wek mînak, porê hevdu diqetandin." (20 salî) "Ji ber ku ez li maleke niştecihbûnê dijîm, me neçar ma ku rêzikan ji her kesî hişktir bişopînin, ji ber ku dîsa rêbernameyên malên niştecihbûnê 'li gorî rêbernameyên hikûmetê biçin' bûn û ew ê li dijî gotinên hikûmetê neçin... Her çend destûr hat dayîn ku her kes 10 hûrdem bimeşe jî, em ne... Malên niştecihbûnê pir hişk in." (20 salî) |

Têkiliyên li malê têk diçin

Di hin rewşan de ku zarok û ciwanan di dema pandemiyê de li malê zehmetiyan kişandine, ev yek wekî sedema têkçûna têkiliyên di navbera wan û mezinên di malê de hatiye wesifandin. Ciwanek di lênêrîna zarokan de vegot ku çawa di hundurê malbata xwe ya xwedîkirî de asê mayî tengezariyên heyî zêde kiriye û bicihkirin hilweşiyaye. Piştre ji hêla lênêrîna civakî ya zarokan ve piştgirî lê hat kirin da ku derbasî jiyanek nîv-serbixwe bibe, lê vegot ku dema li benda vê yekê bû, li mala xwe ya xwedîkirî maye û zehmetî kişandiye.

| "Bê guman, mîna, tenê, mîna, me bi awayekî xelet hejand, ez texmîn dikim, û mîna giyayê ku pişta deve şikand. Ez difikirim ku em jixwe ber bi wê rêyê ve diçûn lê ez difikirim ku heke em her dem di malê de bi hev re ne asê nebûna, dibe ku... neba... dibe ku bi awayekî cûda biqediya heke Covid tunebûya... Ew pêvajoyek dirêj bû [barkirin]… wekî, gava ez li ser difikirim, du meh jiyan bi mirovên ku, wekî, tu ne malbata te yî - wekî, ew malbata te ne lê tu êdî ne malbata te yî pir xemgîn û trawmatîk e… Min, wekî, bi xizmetên civakî re li ser çûna terapiyê axiviye ne ji ber ku ez xemgîn im lê ji ber ku ez hîs dikim ku gava tu ji gelek tiştên trawmatîk derbas dibî, mejiyê te wan digire û ez bi rastî dixwazim wan tiştan vekim.” (20 salî) |

Zarokekî din rave kir ku pandemiyê çawa bi awayên cûrbecûr bandor li têkiliya wî bi dê û bavê xwe yê neviyê re kiriye, di nav de nakokiyên li ser agahdariya xelet a Covid-19, û di dawiyê de hişt ku ew têkiliyê qut bike.

| "Ji ber vê yekê di dema pandemiyê de mîna ku ez û bavê min [bi hev re dijiyan] bû, û dû re jî mîna parvekirina welayetê di navbera min û bavê min, min û diya min de, lê tişt bi diya min re hinekî ecêb bûn… Ji ber Covidê, di navbera min, diya min û bavê min ê xalbendî de şikestinek mezin çêbû… Me di warê Covidê de li ser gelek tiştan li hev nekir… Hûn ewqas dem bi endamên malbatê re derbas dikin ku hûn dest pê dikin ku fêm bikin ka hûn li ser wan çi hez nakin, û ez bê guman gihîştim têgihîştinek mezin a mîna ku ez çiqas tercîh dikim ku bi bavê xwe re bijîm ji jiyana bi diya xwe re… Di dema Covidê de mîna ku [bavê min ê xalbendî] tenê bawer dikir bi gelek teoriyên komployê… wê hingê ew dixwest hewl bide ku bêje ku raya we xelet e, ji ber ku siyasetmedarên wî x, y, û z gotibûn, ew tenê mîna bû, di wê gavê de wî hîs kir ku raya wî ji, hûn dizanin, raya min derbasdar an rasttir e… Ji ber vê yekê mîna ku ez û bavê min bêtir girêdanek çêbû, ez û diya min hêdî hêdî dest bi windabûnê kirin, ku bi rastî piştî Covidê berdewam kir… Min ew du sal in nedîtiye… Ez difikirim ku tenê ewqas nerazîbûn hebû mîna ku di hundir de asê maye, ew, dizanî, zirarê dide endamên malbatê.” (17 salî) |

Hin ji kesên ku hevpeyvîn pê re hatiye kirin, di dema pandemiyê de ji dê û bavên xwe veqetiyane. Yên ku wê demê di temenê xortaniya xwe de bûn, carinan ji şert û mercên pandemiyê haydar bûn ku bûne sedema veqetîna wan. Karantîna dikare ji bo dê û bavên wan jî dijwartir bike ku tevî têkçûna têkiliyê jî, ku ev yek bi taybetî li cîhên jiyanê yên piçûk an jî li cihên qerebalix dijwar bû. Ev nîşan dide ku di hin rewşan de, tengezarîyên di nav malbatan de di dema pandemiyê de bûne sedema guhertinên demdirêj di malan, malbatan û dînamîkan de.

| Dê û bavê min wê demê di rewşeke cudabûnê de bûn… ji ber vê yekê ev yek pir xemgîn bû… [Di warê guhertinên têkiliyên malbatê de, tu guhertinên erênî tune bûn]… mîna ku rewşa malbata min ji bo dê û bavê min xirabtir dibe.” (21 salî)

"Ji ber vê yekê wê demê dê û bavê min di heman malê de dijiyan... Lê ew ji hev cuda bûn, ji ber vê yekê ew demek pir, pir dijwar bû... di ode û tiştên cuda de... ew di heman malê de ne, lê ew tenê nediaxivîn." (22 salî)"Ji ber vê yekê wê demê dê û bavê min di heman malê de dijiyan... Lê ew ji hev cuda bûn, ji ber vê yekê ew demek pir, pir dijwar bû... di ode û tiştên cuda de... ew di heman malê de ne, lê ew tenê nediaxivîn." (22 salî) |

Jiyana li xanîyên qerebalix

Ev lêkolîn ji hevpeyvînên bi zarok û ciwanên ku li qerebalix cih di dema pandemiyê de. Kesên ku di cihên qerebalix de hatine hevpeyvînkirin, zarok û ciwanên ku mafê wan ê xwarina dibistanê ya belaş heye, bi lênêrîna civakî ya zarokan re di têkiliyê de ne û bi xizmetên tenduristiya derûnî re di têkiliyê de ne, bûn. Wekî din, hin zarok û ciwanên ku di cihên qerebalix de dijîn, kesên ku lênêrîn ji dest dane an jî penaxwaz bûn.

Ezmûnên takekesî li gorî şert û mercên taybetî diguherin, lê divê were zanîn ku di dema pandemiyê de gelek caran zehmetiyên ji ber qerebalixiya wargehan ligel zehmetiyên din jî hatine jiyîn. Di nav van zehmetiyên ku berê hatine vegotin de, û her weha li hember nexweşî, şîn, an jî parastina ji nişka ve hebûn. Di dema qedexeyê de di maleke qerebalix de asê man û tengezî an jî stresên heyî di nav malbatê de zêde kirin û ji bo vê komê zehmetiyên nû yên pandemiyê dijwartir kirin. Ev bandora tevlihev a li hember gelek zehmetiyan di carekê de nîşan dide.

| "Ez ê bêjim [karantînayê û jiyana li cîhek qerebalix bi malbatê re] bê guman bandor li ser têkiliyên min bi malbata min re kir… [bêyî wê] ger ez li cîhekî cuda ji malbata xwe bûma, ew celeb zext li ser têkiliya me nedibû." (20 salî) |

Zarok û ciwanan girîngiya hebûna odeya xwe ya taybet destnîşan kirin, her çend malbat qerebalix be jî. Wan hîs kir ku hebûna cîhek ji bo rihetbûn û nepenîtiyê dibe alîkar. Yên ku odeya xwe ya taybet tunebû rave kirin ku wan hîs dikir ku ger cîhek wan a taybet hebûya, dê ji bo wan hêsantir bûya ku bi pandemiyê û bi giştî bi şert û mercên jiyana xwe re mijûl bibin.

| "Berî [cihê ku ez di dema pandemiyê de lê dijiyam], bi gelemperî odeya min a taybet hebû… Ez ji dibistanê, karekî an tiştekî din dihatim hundir, dizanî? Werin hundir û tenê rihet bibin, wext hebe ku bifikirin… Cihê min ê rastîn tunebû." (22 salî) |

Kesên ku di dema pandemiyê de bi malbata xwe re di şert û mercên qerebalix de dijîn, rageşiya li malê di navbera endamên malbatê de wekî tûjtir wesifandin dema ku zarok û ciwan an dê û bavên wan jixwe di bin stresê de bûn, an jî mal wekî cîhek ewle an rihet hîs nedikir. Ciwanek behsa dijwarîyên parvekirina odeyên razanê yên gelek endamên malbatê û awayê ku ev rewşa jiyana qerebalix dijwarîyên din, di nav de stresa li ser darayî, zêde dike, kir. Rewş hîn dijwartir bû ji ber ku îstîsmara navmalî ya di navbera dê û bavan de di nav malbatek qerebalix de pêk dihat. Vê ciwanê rave kir ku lênêrîna civakî di destpêka pandemiyê de ji tevgera bavê xwe agahdar bûbû, lê cîhek din tunebû ku wî lê bihewîne, ji ber vê yekê her du dê û bav berdewam di heman malê de bi hev re dijîn.6

- 6 Ev keça ciwan niha bi serbixwe û nêzîkî diya xwe dijî. Diya wê êdî di heman malê de bi bavê xwe re najî.

| "Bi gelemperî, odeya herî mezin [ew odeya ku] diya min û her du birayên min [di xew de bûn] ye. [Û dû re li malê rewş xirabtir bû] Ez difikirim ji ber ku [dê û bavê min] neçar bûn ku her tim [li hundir] bimînin. Ez difikirim ku bavê min pir bi derketina derve ve hatibû ragirtin. … Ew bi rastî nedixwest rêzikan bişopîne ji ber ku ew digot, hûn dizanin, ew ji mayîna li malê pir bêzar bû. … [Dê û bavê min] her tim li hev dixistin. Tiştên mîna fatûreyan zêde dibûn û hewl didan ku wê birêve bibin. Û her weha hewl didan ku serlêdana tiştên mîna, hûn dizanin, betlaneya bêkar… Gelek nîqaş li ser pere û tiştên weha hebûn." (18 salî) |

Rewşa qerebalixiyê rasterast bi kêmbûna rehetî û tenduristiya derûnî di dema pandemiyê de ve girêdayî bû ji hêla hin zarok û ciwanan ve, yên ku bi nebûna cîh û nepenîtiyê, û her weha nekarîn hevalên xwe bibînin an çalakiyên ku jê hez dikirin bikin, têkoşiyan.