Some of the stories and themes included in this record contain descriptions of bereavement, verbal and physical abuse, mental health impacts, and significant psychological distress. These may be distressing to read. If so, readers are encouraged to seek help from colleagues, friends, family, support groups or healthcare professionals where necessary. A list of supportive services is provided on the UK Covid-19 Inquiry website.

মুখপাত্র

Module 10 is the final of the Inquiry’s modules examining the pandemic’s impact on society. Three Every Story Matters records have been produced for the Module 10 investigation:

- this record covering the experiences of bereavement during the pandemic;

- a record on the impact of the pandemic on mental health and wellbeing; and

- a record on experiences of key workers during the pandemic.

Every Story Matters closed to new stories in May 2025, so records for Module 10 analysed every story shared with the Inquiry online and at our Every Story Matters listening events up until this date. These records represent the totality of what we have heard on these topics.

Throughout the Inquiry, we have been listening to bereaved people about their experience of the pandemic. For this record, we ran a series of listening events to enable bereaved people to further discuss the impact of their loss with us and each other. This record has been shaped by the stories, thoughts and reflections from those events. These are signalled in pink boxes throughout the document. We are grateful to everyone who took part in these events or who shared their experiences online.

In the huge numbers of stories that we heard, people across the UK told us of the immense suffering they experienced in losing a loved one during the pandemic. Many were denied the chance to say goodbye. Initial feelings of shock and disbelief gave way to guilt and anger because they had not been able to be with their loved ones during their final moments.

The anguish felt by bereaved people was made worse by the restrictions on funerals, burials and end of life ceremonies. This often meant not being able to hold a funeral according to their loved one’s wishes or according to their customs.

Bereaved people were cut off from friends and family at the time when they needed their support the most. Many continue to feel guilty about whether they did enough for their loved ones at the end of their life. They were left alone to dwell on these thoughts, leading to long term, traumatic grief.

It was particularly upsetting for those who abided by the rules and denied themselves the opportunity to say goodbye as their loved one would have wanted, to then hear of lockdown breaches reported in the media. Bereaved people told us about how angry this made them feel, adding to their grief.

Many bereaved people continue to suffer. While they see the world moving on from the pandemic, some feel abandoned and forgotten. Many sought support in others with shared experiences, with such groups helping people to process their loss. For some, those groups gave them the strength they needed to press for accountability and change – so that people in the future do not have to suffer in the same way they did.

We know that sharing stories of loss and grief can be extraordinarily hard and we thank those of you who did so, whether online or at events. Your stories and reflections have been invaluable for this record of pandemic bereavement and will support the Chair of the Inquiry in making her findings.

স্বীকৃতি

The team at Every Story Matters would also like to express its sincere appreciation to all the organisations below for helping us capture and understand the voice and experiences of people who were bereaved during the pandemic. Your help was invaluable to us reaching as many communities as possible. Thank you for arranging opportunities for the Every Story Matters team to hear the experiences of those you work with either in person in your communities, at your conferences, or online.

To the Bereaved, Mental Health and Wellbeing, Key Workers, Equalities, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland forums, we truly value your insights, support and challenge on our work. Your input was instrumental in helping us shape this record.

কেয়ারার্স ইউকে

বিচারপতি সিমরুর জন্য কোভিড-১৯ শোকাহত পরিবার

Covid19FamiliesUK

অক্ষমতা অ্যাকশন উত্তর আয়ারল্যান্ড

Disability Equalities Scotland

হসপিস ইউকে

Members of Covid-19 Bereaved Families for Justice UK

মুসলিম মহিলা পরিষদ

উত্তর আয়ারল্যান্ড কোভিড-১৯ শোকাহত পরিবার বিচারের জন্য

স্কটিশ কোভিড শোকাহত

দক্ষিণ এশীয় স্বাস্থ্য কর্মকাণ্ড

WAY Widowed and Young

ওভারভিউ

This short summary provides an overview of the themes from the many stories we heard about bereavement during the pandemic.

গল্পগুলি কীভাবে বিশ্লেষণ করা হয়েছিল

Every story shared with the Inquiry is analysed and will contribute to one or more themed documents called records. These records are submitted from Every Story Matters to the Inquiry as evidence. This means the Inquiry’s findings will be informed by the experiences of those most affected by the pandemic.

In this record contributors describe their experience of bereavement during the pandemic, how this has affected them and continues to impact their lives. All contributors to this record had a loved one, family member or friend die during the pandemic.

The Inquiry team and researchers have:

- Analysed 55,362 stories shared online with the Inquiry, using a mix of natural language processing and researchers reviewing and cataloguing what people have shared.

- Conducted 66 in-depth interviews with people who were bereaved during the pandemic.

- Hosted six listening events and six consultative workshops with bereaved people to design these events. This included three reflective workshops to understand which experiences people wanted us to emphasise in this record.

More details about how contributors’ stories were brought together and analysed for this record are included in the Introduction and in the Appendix. This document reflects different experiences without trying to reconcile them, as we recognise that everyone’s experience is unique.

Some stories are explored in more depth through quotes and case illustrations. These have been selected to highlight specific experiences. The quotes and case illustrations help ground the record in peoples’ own words. Contributions have been anonymised.

What we heard from bereaved people

Pandemic restrictions meant many people were unable to be with their loved ones at the end of their life. In some cases, this meant the last time they saw their loved one was when they were taken away in an ambulance or before they went into hospital or a care setting. Many bereaved people experience ongoing and profound feelings of anger, sadness and guilt that they could not be with or comfort their loved ones at the end of their life. The pandemic impacted the ability of families and friends to conduct funerals, burials and end of life ceremonies in line with their wishes, including cultural and religious practices. Contributors told us how the uncertainty about what happened to their loved ones in their final days was heartbreaking, often leaving them with many questions about their death.

| " | The pain and stress we are still going through … I can’t live life not knowing how our mum died or knowing how we can find out those answers. It’s hell not knowing why she died … It’s frustrating and soul destroying not knowing answers to questions we have and we can’t even grieve properly for her.”

– Bereaved daughter, Wales |

As the pandemic continued, other bereaved family members were able to visit loved ones in hospital or in care settings to be there at the end of life. However, the pandemic restrictions meant they could not spend as much time with their loved one as they would have liked or be close to them to offer comfort.

Many contributors said they felt like they had let their loved one down because they could not speak up for them and support them in the way they normally would. They described replaying decisions in their mind and asking themselves whether they could have done something differently at the end of their loved one’s life. This guilt and regret has made it incredibly difficult for many bereaved people to process their grief.

| " | My sister and I will always have to live with the guilt … that a vulnerable elderly person should be allowed to die alone, to be deprived of her daughters, the only people that she still recognised and that she relied so heavily on for her daily care … we thought the hospital was the safest place for her but it wasn’t … we still struggle with the [guilt and grief] every day. I am so sorry that we let her down.”

– Bereaved daughter, Wales |

Family members told us that the complex and often traumatic nature of bereavement had a profound impact on their mental health. Some whose loved ones died because of Covid-19 described developing an ongoing fear that they, or other family members, might also become ill and die. Others shared experiences of deep sadness, worry and depression. Many continue to struggle with their mental wellbeing, living with painful memories and vivid recollections of what happened to their loved ones.

Bereaved people also faced practical and administrative challenges after the death of their loved ones, at a time when many organisations were struggling to manage the effects of the pandemic. This added further distress and difficulty to an already painful period of bereavement. Some told us how insensitive they found the collection of personal items from hospitals, care homes or hospices, often receiving them in bin bags or missing treasured items.

After their loved one died, family members had to manage processes like closing bank, utility and other accounts while struggling to accept that their loved one had actually died. Some contributors faced practical problems finding or getting access to the right information and finding the right person to speak to for help after their loved one died. Contributors also discussed how companies and organisations did not adapt their processes to take into account how upsetting their loss was in the circumstances of the pandemic.

| " | Banks, building societies, offices … all of them were working from home on limited hours. I spent days on hold … I repeat that only those who suffered a bereavement at the time know how difficult it was … I wanted peace, and all I got was frustration, obstacles, excuses from these companies.”

– Bereaved daughter, Northern Ireland |

Impact on funerals, burials, cremations and other end of life ceremonies

Family members described painful and challenging circumstances when planning funerals, burials, cremations and end of life ceremonies. There were delays in certifying deaths and reduced capacity in mortuaries, leaving families unsure when they would see their loved ones or mark their deaths.

Pandemic restrictions placed severe limits on funeral attendance and social distancing measures kept mourners apart. Many people were deprived of the comfort that comes from being close to family and friends and from receiving support through simple but powerful gestures of care and human touch. As a result, funerals often felt more isolating, with the absence of these essential support networks compounding people’s grief. The limits on who could attend funerals, cremations and burials also created painful choices and in some cases, tensions within families. During the pandemic, frequent changes in restrictions and inconsistencies in local guidance about attendance rules caused further stress, leaving families scrambling to make difficult last-minute arrangements.

| " | When my dad died, various restrictions had come in. I discovered that he had a funeral plan and because of the restrictions, we couldn’t use everything in the plan … We couldn’t use the crematorium that we would have done because it was limited to 10 people.”

– Bereaved son, England |

Over time, easing guidelines meant that families could follow more of the cultural and religious practices that were deeply significant to them and their loved ones who had died. Despite obstacles, some funeral directors showed immense empathy, ensuring funerals and end of life ceremonies were carried out in line with the families’ wishes wherever possible.

| " | We were so overwhelmed with grief and sadness [at the funeral] … but the minister and funeral director were very supportive … and extremely kind.”

– Bereaved daughter, Scotland |

Friends and family members said they lost the opportunity for gatherings to honour their loved ones and to celebrate their life, even after restrictions had begun to ease. They reflected on the pain they felt because they would never get those opportunities back. For some people from different religious and cultural backgrounds, not being able to conduct their traditional ceremonies left many feeling anxious about their loved one’s spiritual journey.

| " | We [normally] have a gathering at the mosque where we sit and we read a lot of prayers. So, like, the ladies, we have a three-day funeral at the mosque where they pray, and then we have, it’s called a little prayer at the end where we have food, put food on it and we make a prayer. We believe that the soul comes and sees the food that they have, and we couldn’t have that.”

– Bereaved daughter-in-law, England |

Many bereaved families also told us how angry and let down they felt about the alleged rule breaking by politicians and other public figures. The bereaved followed the rules and could not honour or say goodbye to their loved ones as they would have wished, yet those who made the rules broke them. This increased their pain and distress.

| " | I think the whole thing with Partygate, for so many people, that tied into what they were doing on that date. How they were adhering to the rules because of a loved one’s funeral … and they were being flouted by the government on the same day. And the raft of the denial, there would be excuses about, you know, ‘Well, we were under so much pressure. We deserved it.’, and you kind of think, ‘Well, what kind of pressure do you think the families were under?’”

– Bereaved person, England |

শোক সমর্থন

Bereaved people found it difficult to access bereavement support services during the pandemic. Many had little information about what was available or found it hard to get in contact with services. Contributors said they often found support through searching online, social media and friends and family. Hospitals, hospices, funeral directors, and GP surgeries sometimes provided information, but this was often signposting to other services.

When people did get in contact with support services, they often encountered delays, with long waiting lists as support organisations tried to respond to increased demand for their help. Some contributors who accessed online services found them helpful, but others felt they lacked personal connection. They also felt that support services struggled to understand the specific experience of bereavement during the pandemic, which meant support was not helpful for some.

| " | When I contacted them, basically I was just on a waiting list for, I don’t know, it must have been about a year. And then I had Zoom sessions with this lady, and she was a lovely lady, but I felt that I didn’t really get that much out of it because I was that much further on and she was more about the basics of grief and that type of thing. And I probably needed more than that by that stage.”

– Bereaved wife and daughter, England |

Some bereaved contributors accessed support through workplace schemes, while others were reluctant to seek support as they did not want to put more pressure on services or they felt they could cope alone.

| " | I was aware of support services, but I felt I’ve never used them. I’ve had so much bereavement [in my life] … and I’ve always coped. So, I looked at it, like, you’re just going to have to cope.”

– Bereaved friend, England |

Many contributors discussed how important and helpful peer support groups were. These groups allowed people to share their experiences with other people who knew what they were going through. This helped many to process their grief and help them feel less alone.

| " | I found peer support, people who understand because they’ve been through something similar or even the same situation sometimes, but there’s that general overall understanding of the emotions, the guilt, the whole thing and I think that is really important. I mean … think, yes, until you’re in it, you don’t know about it.”

– Bereaved wife, England |

Long term impact of bereavement

Bereaved contributors shared how pandemic restrictions left them feeling isolated and alone, cut off from family, friends and support networks. Many described how this deepened their trauma and sorrow as they tried to process their grief. The isolation took a toll on their mental health, heightening feelings of sadness, worry, anxiety and depression. For some, the strain affected family relationships, making it harder to communicate and reach out for help when they needed it most.

For some contributors, their loved one’s death had a financial impact, especially when their deceased loved one was the main earner in the household. Individuals found that Bereavement Support Payments1 were inadequate. They also found the extra pressure of additional responsibilities of caring for children, parents and friends during the pandemic led to further economic pressure.

| " | [When my partner died] I had to go back to work straight away. I didn’t even get to have proper bereavement … I had to support [my mum] until we found out she could have some benefits, to apply for her. So, we started to apply for Universal Credit [and] find out what was available.”

– Bereaved wife, England |

When pandemic restrictions were lifted and society started to open again, some contributors said this worsened their grief and they found themselves revisiting the trauma of their loved one’s death. The constant media coverage of the pandemic and the sense that others wanted to move on were painful and upsetting for many bereaved people. Some felt that others wanted to forget about the devastating loss they had experienced.

| " | It doesn’t help that you come across people and the media and everyone, it feels like they are saying ‘Well you’ve got to move on. [The pandemic] is done now … it’s time to forget about this’ … or they don’t believe it was real.”

– Bereaved wife, England |

Lessons to be learned

Bereaved people told us it is very important the UK Covid-19 Inquiry leads to justice and accountability for the decisions that were made and the resulting impacts during the pandemic. They want to see honesty about what went wrong so that lessons can be learned about what should be done differently in the future.

| " | There has to be accountability, some terrible decisions were made and we need to know why … what is left is the actual truth, and the actual facts.”

– Bereaved person, Wales |

Many contributors would also like to see a greater focus on care and compassion when designing restrictions and guidelines around funerals, burials and end of life ceremonies. They felt restrictions should be more compassionate, allowing larger numbers of family and friends to attend so people do not feel so alone. When looking to the future, contributors also highlighted the importance of remembrance and commemoration for their loved ones.

| " | [Our loved ones] didn’t have dignity in death so we must make sure that they have dignity now in remembering … we need to look at ways in which it can be remembered, you know, in a beautiful way for us, for them, and make sure they’re not forgotten and what they went through.”

– Bereaved daughter, Wales |

Bereaved family members and friends would like to see meetings with healthcare professionals prioritised so they can ask questions and understand how their loved one was treated at the end of their life. This would help bereaved people process their grief.

In terms of bereavement support, contributors said that in future pandemics there should be better guidance and signposting to support services. They also emphasised the importance of organisations taking a more proactive approach. For example, healthcare services, care homes or hospices reaching out to bereaved individuals to offer support. Contributors would also like to see more in-person support sessions wherever possible. They felt this would be much more effective in helping build relationships and trust with support providers.

Bereaved people also felt the importance of peer to peer support should be reflected in future pandemics. They would like to see support from healthcare organisations, bereavement organisations and national and local government in the form of funding and facilitation to ensure peer support can continue.

| " | In our local area now there are bereavement cafés, so, people that are bereaved can go and meet up, just have a coffee and there are a couple of [bereavement] professionals there at the same time … I think people often find just chatting and listening to other peoples’ stories makes you feel less alone, because it is a very lonely experience … maybe having certain services that you can contact, just people who will understand a bit more and that you’re perhaps not going to have to pay for.”

– Bereaved wife and daughter, England |

- Bereavement Support Payments give financial support to people for a period after the death of a partner, made up of a lump sum followed by monthly payments over 18 months.

1 Introduction

This document reflects the stories which contributors have shared with the UK Covid-19 Inquiry about the death of someone close to them during the pandemic, highlighting the deep emotional and practical challenges that continue to affect their daily lives.

পটভূমি এবং লক্ষ্য

Every Story Matters is an opportunity for people across the UK to share their experience of the pandemic with the UK Covid-19 Inquiry. Every story shared has been analysed and the insights derived have been turned into themed records for relevant modules. These records are submitted to the Inquiry as evidence. In doing so, the Inquiry’s findings and lessons to be learned will be informed by the experiences of those impacted by the pandemic.

The record brings together what contributors told us about the impact of the pandemic on their experience of bereavement.

Some topics have been covered in other Module 10 records or the records from other modules. Therefore, not all experiences shared with Every Story Matters are included in this document. You can learn more about Every Story Matters and read previous records at the website: https://covid19.public-inquiry.uk/every-story-matters.

লোকেরা কীভাবে তাদের অভিজ্ঞতা ভাগ করে নিয়েছে

There are several ways in which we heard from different types of people about their experiences of bereavement during the pandemic.

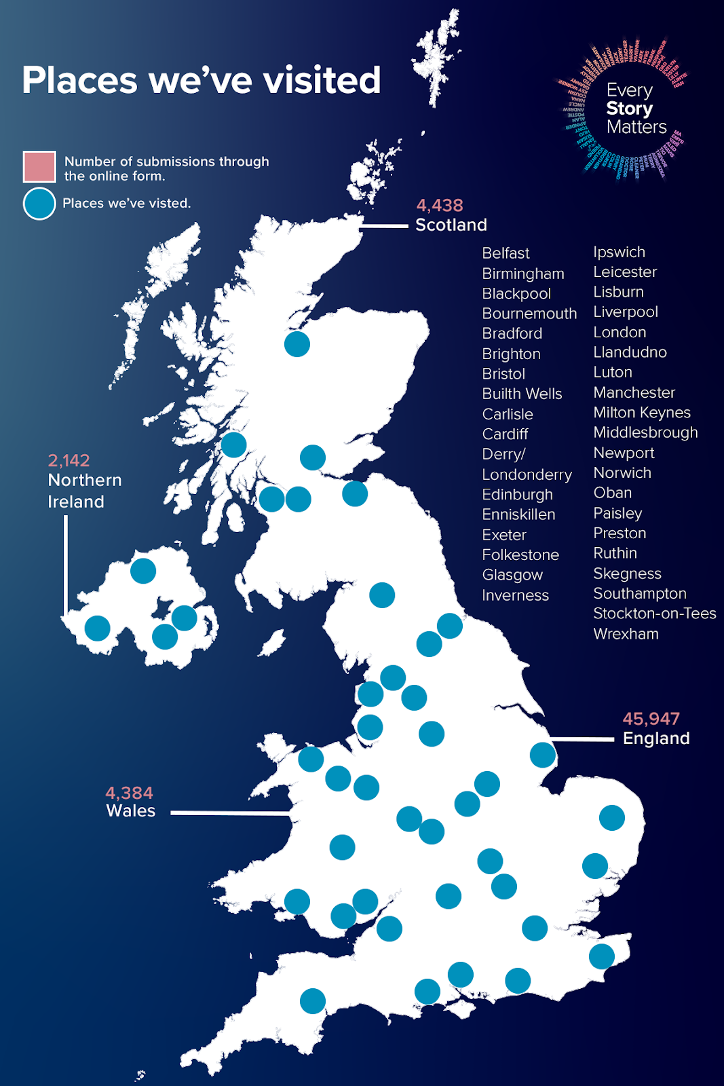

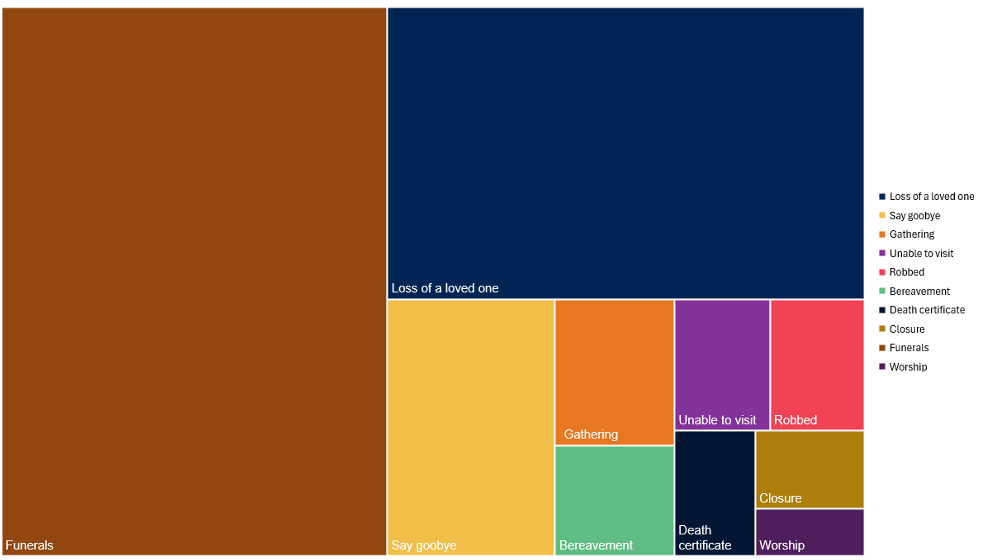

Stories shared via the Inquiry website

We invited members of the public to complete an online form via the Inquiry’s website (paper forms were also offered to contributors and included in the analysis). This asked them to answer three broad, open-ended questions about their pandemic experience. The form asked other questions to collect background information about them (such as their age, gender and ethnicity). This allowed us to hear from a very large number of people about their pandemic experience. All of the responses to the online form were submitted anonymously. For Module 10, we analysed the final set of stories submitted to Every Story Matters online. This consisted of 55,362 stories with 45,947 from England, 4,438 from Scotland, 4,384 from Wales and 2,142 from Northern Ireland (contributors were able to select more than one UK nation in the online form, so the total will be higher than the number of responses received). The responses were analysed through natural language processing (NLP), which helps organise the data in a meaningful way. Through algorithmic analysis, the information gathered is organised into ‘topics’ based on terms or phrases. These topics were then reviewed by researchers to explore the stories further (see Appendix for further details). These topics and stories have been used in the preparation of this record.

We commissioned researchers to conduct 66 interviews with people who were bereaved during the pandemic across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. These interviews took place between April and June 2025.7 In-depth interviews were recorded, transcribed, coded and analysed to identify key themes relevant to Module 10.

Bereaved Listening Events

We took a consultative approach to listening to bereaved people so that they were able to shape how the Inquiry listened to and learned from experiences of bereavement during the pandemic.

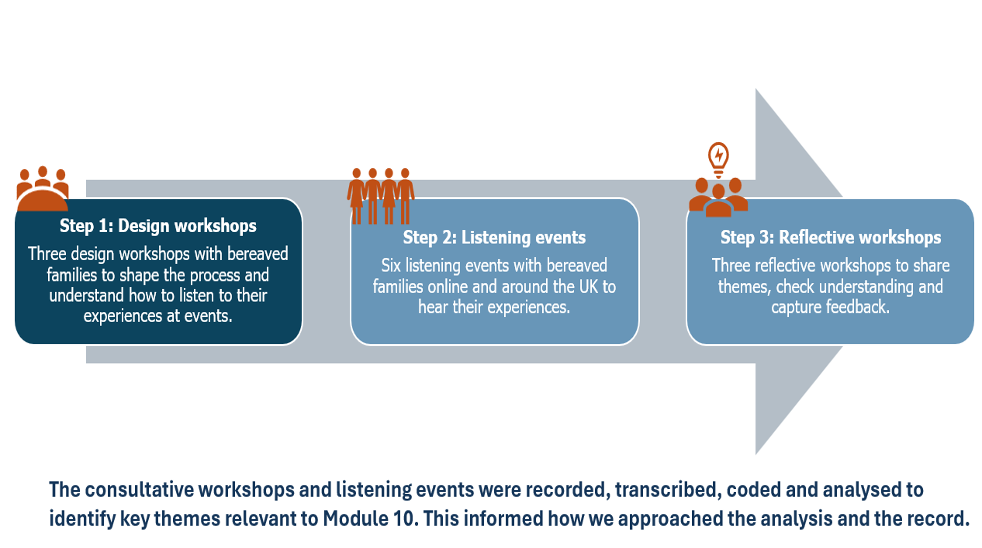

Figure 1: Summary of consultative workshops

In January 2025, we held three design workshops with bereaved people who helped us develop a series of Listening Events. Contributors who attended these workshops included members of the Inquiry’s Bereaved Forum.2 They shared their views on the length of the events, the best place to host the events, how to create a safe and comfortable space for people to share their experience, the language we should use, and who we should invite.

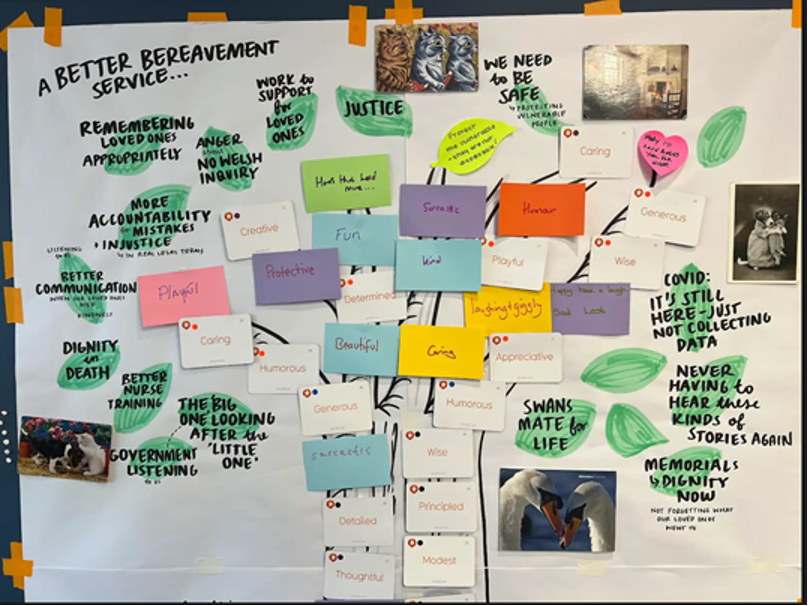

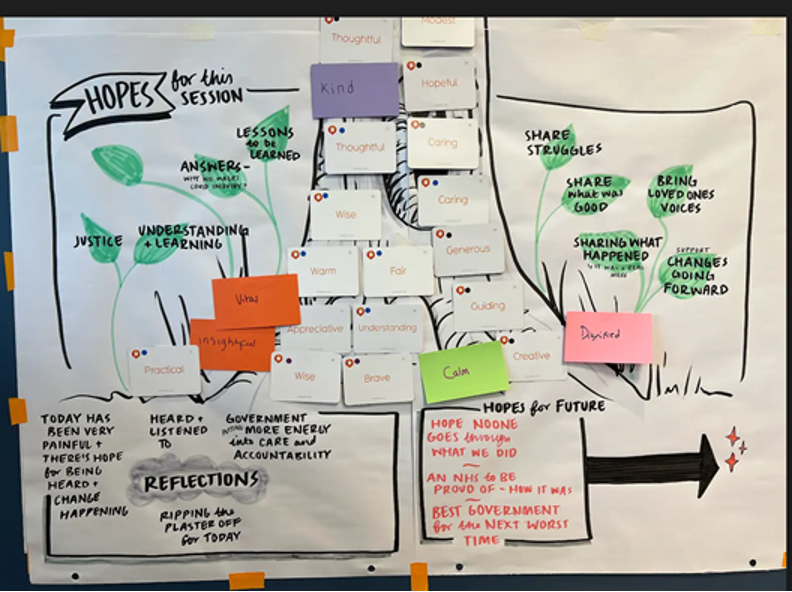

Feedback from the consultative workshops was used to design six Listening Events held with bereaved people between May and June 2025, three online and three in-person events in Brighton, Glasgow and Cardiff. These events were advertised via the Inquiry newsletter and through peer support groups for people who were bereaved during the pandemic. These allowed bereaved people to share their experiences of bereavement during the pandemic, the impact on burials and end of life ceremonies, accessing bereavement support and learning for the future. These events were designed to recognise the trauma that people had experienced and were still experiencing, to be engaging and interactive, and to enable peer support. We worked in small groups to explore people’s experiences and to think about themes and identify learning for the future. There were counsellors available to support people in each of the small groups, as well as expert, trauma trained facilitators. We used visual and interactive tools and resources to support the conversations. Throughout the sessions, contributors at the listening events were encouraged to add their thoughts, views, reflections and memories of their loved ones to an event ‘tree’. The purpose of the tree was to provide participants with the opportunity to acknowledge their loved ones by adding words to describe the person that they were remembering. It was also used for activities that invited participants to add key reflections about their hopes for the session and learning for the future. See Figure 2 below.

After the listening events, a further three reflective workshops were held in July 2025 and attended by bereaved people, some of whom had taken part in previous events. Similarly, opportunities to attend the reflective workshops were advertised via the publicly available Inquiry newsletter and through peer support groups for people who were bereaved during the pandemic. We shared with contributors what participants had told us at the Listening Events and sought their views on the best way to represent these themes throughout this record. Contributors had the opportunity to hear from each other and discuss which themes they felt were most important to emphasise in the record.

Figure 2: Example of listening event tree

Reflections from bereaved listening events

We have drawn out the themes and reflections from these workshops in this record. They are in boxes titled ‘Reflections from Bereaved Listening Events’ and summarise the points that workshop participants collectively told us they want to be emphasised in this record.

Public listening events

The Every Story Matters team went to 43 towns and cities across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to give people the opportunity to share their pandemic experience in person in their local communities. We worked with many charities and grassroots community groups to speak to those impacted by the pandemic in specific ways. Short summary reports for each event were written and used to inform this document. While these events were not specifically designed for those who had experienced bereavement, many individuals whose loved ones died during the pandemic still chose to share their stories there.

In addition, the Chair of the Inquiry, Baroness Heather Hallett, met with bereaved individuals at listening events in each nation of the UK. We would like to thank the following organisations for helping to organise this:

- Covid-19 Bereaved Families for Justice UK

- বিচারপতি সিমরুর জন্য কোভিড-১৯ শোকাহত পরিবার

- উত্তর আয়ারল্যান্ড কোভিড-১৯ শোকাহত পরিবার বিচারের জন্য

- স্কটিশ কোভিড শোকাহত

The locations where Every Story Matters listening events were held is shown below:

Figure 3: Every Story Matters listening events across the UK

গল্পের উপস্থাপনা এবং ব্যাখ্যা

It is important to note that the stories collected through Every Story Matters are not representative of all experiences of bereavement in the pandemic. We are more likely to hear from people who wish to share a particular experience with the Inquiry. The pandemic affected everyone in the UK in different ways and while general themes and viewpoints emerge from stories, we recognise the importance of everyone’s unique experience of what happened. The record does not represent the views of the Inquiry. It aims to reflect a range of experiences shared with us, without attempting to reconcile differing accounts.

We have tried to reflect the range of stories we heard about bereavement, which may mean some stories presented here differ from what other, or even many other, people in the UK experienced. Where possible we have used quotes to help ground the record in what people shared in their own words.

Some stories are explored in more depth through case illustrations within the main chapters. These have been selected to highlight the different types of experiences we heard about and the impact these had on people. Contributions highlighted in case illustrations have been anonymised and written to expand upon the main themes from our analysis of the stories shared with the Inquiry. Stories were collected from 2022 to 2025 and analysis took place in 2025, meaning that experiences are being remembered sometime after they happened.

রেকর্ডের কাঠামো

This document is structured according to the scope of Module 10, which is investigating the impact of the pandemic on society, including the most vulnerable, with a particular focus on the bereaved, key workers and mental health and wellbeing.3

It starts by outlining bereaved people’s experiences of a loved one dying during the pandemic (Chapter 2). It then explores the impact of the pandemic on funerals, burials and end of life ceremonies (Chapter 3). It describes experiences of accessing bereavement support (Chapter 4) and the long term impacts of bereavement (Chapter 5). Finally, it sets out the lessons contributors think can be learned for the future (Chapter 6).

- A mailing list that is maintained by the Inquiry of bereaved volunteers who wish to participate in opportunities to shape the Inquiry’s work.

- The full scope of Module 10 is outlined in the appendix of this document.

2 The death of a loved one during the pandemic

This chapter covers what family and friends told us about the death of a loved one during the difficult and often isolating circumstances of the pandemic. Many described the heartbreak of not being able to be by their loved one’s side when they were dying. For some, the last time they saw them was as they were taken away in an ambulance, or just before they entered hospital or a care home.

People spoke about the pain of knowing their loved one was alone at the end of their life, without the comfort of a familiar face, a hand to hold, or able to say the words they wanted to say. They described feeling helpless and unprepared, the suddenness of events leaving them in shock and disbelief. The distance imposed by restrictions added another layer of sorrow to an already devastating bereavement.

The pandemic restrictions meant many family members and friends were unable to be with their loved ones at the end of their life. This meant that the last time they saw their loved one was when they were taken away in an ambulance or before they went into a hospital or care setting. Many bereaved people said they felt completely unprepared and shocked when their loved one died.

| " | You never prepare yourself for somebody passing on, especially if you see them today, and then they’re coughing tomorrow. The next day, they can’t breathe. Do you know what I mean? It was so, so quick. I remember, we didn’t have a chance to even say goodbye, because the moment that she left the house, and went to the hospital, we couldn’t visit her. I think, from the day that she knew, she passed on within five days.”

– Bereaved niece, England |

| " | I begged for me and my sister to be with Daddy when he died, we weren’t even given that. Different trusts had different rules, some were allowed with them, and we weren’t, it was absolutely horrendous.”

– Bereaved daughter, Northern Ireland |

| " | Mum was left without oxygen for four days, they didn’t expect [her] to live as long. We were only allowed in one at a time, each day it was a different family member. After she died Dad was still in ICU, he’d just lost my mum and we were not allowed to see him.”

– Bereaved person, Scotland |

Contributors experienced ongoing and profound feelings of anger, sadness and guilt that they could not be with or comfort their loved ones at the end of their life. Many are devastated that their loved one may have felt abandoned at the time they most needed support and love from family and friends.

| " | The more I reflect on the fact that I was unable to visit for the last 10 months of her life, I feel increasingly guilty that she died believing she’d been abandoned. I feel robbed of being able to say goodbye and I’m aware that my mental health has been affected by my feelings of guilt, anger and sadness which I will have to live with forever.”

– Bereaved person, England |

The uncertainty about what happened to their loved ones in the final days has left many family members heartbroken. These unanswered questions about the death of their loved one have often had a detrimental impact on mental health and complicated their grieving process.

| " | We lost our daddy early January 2021. He was 68, life and soul of the party … it was the most surreal experience and over three years on I have nightmares, did he suffer? Was it him in the coffin? Did we cremate the right person? Amongst a dozen more questions we will never get the answers too.”

– Bereaved daughter, Northern Ireland |

| " | I think the most heartbreaking thing for us was that he passed away on his own, alone, and we don’t know if he was in pain, if he wasn’t in pain, or what was happening. I mean, it just feels unknown, and it has affected us a lot, to be honest. My mum, especially, she went through depression after.”

– Bereaved niece, England |

Many bereaved people said they feel unsure as to whether they did everything they could for their loved ones at the end of their lives. They described replaying decisions in their mind and asking themselves whether they could have done something differently at the end of their loved one’s life. This guilt and regret has made it incredibly difficult for many people to process their grief.

| " | On the day dad died I received a phone call in the afternoon to say he was very unwell. At this point I wanted to come in and be with him but was told that would not be allowed …. I have not really come to terms with this and feel extremely guilty that my brother and I were not there to comfort him in his passing.”

– Bereaved son, Scotland |

Reflections from Bereaved Listening Events

When we discussed bereavement themes with people at the bereaved listening events, they echoed the complex feelings of anger, shock and sadness felt by others, and with which they continue to live.

Contributors said it was important that governments and the wider public understand what happened when their loved ones died and how it impacted them and their families, so future generations do not have to go through such difficult experiences again.

“For me, I think the guilt, the regret, the broken trust, I think that resonates highly with me … I think that was the really significant thing.” Bereaved daughter, Wales

“My inability to have spent any time with my sister at the end of [my niece’s] life or after she died, to actually see her, for me personally, that was very, very distressing. I still don’t feel like I was able to say goodbye in any shape or form, and still 5 years on, I am so emotional about that … I think others, they have very quickly forgotten the things that we weren’t allowed to have available … when I say to people now, it’s like, ‘Oh, I didn’t realise. Oh, I’d forgotten that.’ And I think that’s the danger [if] we don’t capture these things … we must never, ever put people in that position again.” Bereaved aunt, England

Bereaved people said their inability to visit dying loved ones meant that they carried long term guilt about not being able to do more for their loved one.

| " | She died without me seeing her and I could not go to her funeral. She must have felt abandoned and I am sure the isolation contributed to her rapid decline.”

– Bereaved friend, England |

As the pandemic went on, some bereaved people were able to visit their loved ones in hospitals, hospices and care settings before they died. Visits were often through a window, or while wearing PPE. This was heartbreaking for both loved ones and visitors. It felt impersonal and cold and often added to feelings of anger and guilt for contributors.

| " | I was then not allowed to visit until they felt she was imminently about to die and to visit once to say goodbye. She was barely conscious and didn’t recognise me with all my double mask on etc. I ended up actually seeing her twice as she lasted longer than they thought, but basically, she was dying in a room on her own for 3 weeks with no one she loved there to hold her hand and talk to her. I really struggle with this and the guilt even though I had no power to change the rules, I feel a lot of anger that this was allowed to happen. It is not humane. And not logical as if I was all masked up why couldn’t I go in every day.”

– Bereaved daughter, England |

Many people described a sense of shock and disbelief caused by the unexpected and sudden death of their loved one. They said it felt unreal, particularly when they had been unable to visit their loved one before they died. This sense of disbelief has made it harder to accept the bereavement.

| " | It all happened so quickly … my mother had gotten seriously ill and died in hospital. The shock me and my family were in was indescribable. My mother was 50 … I am extremely frustrated … our lives changed forever.”

– Bereaved daughter, Northern Ireland |

| " | I’d say for the first six months to a year, I felt really low. I felt really depressed, but it was, kind of, mixed with disbelief as well that she’s actually gone. You know, so it was like a whirlwind of emotions.”

– Bereaved granddaughter, England |

| " | Devastation. She couldn’t go to the house where [our mum] was living… [my sister] talks to her [mum], and cries, you know, out of the blue. Just be on the bus and start crying. I sometimes wonder if she might have some sort of, not exactly guilt, but something not resolved, yes. She wasn’t expecting her to die.”

– Bereaved daughter, England |

We also heard how some people who were bereaved due to Covid-19 became fearful and anxious because they had witnessed the life-threatening nature of the virus first-hand. They were afraid that they, or their family members, might also catch the virus and die.

| " | My mental health became very horrific over this period. Watching my grandfather pass away from Covid made me extremely more anxious regarding catching Covid or another family member [catching it].”

– Bereaved granddaughter, Northern Ireland |

Cara’s storyCara’s mum and dad both contracted Covid-19 and were taken to separate hospitals, where their health rapidly declined. Cara was unable to visit either of her parents and received very little communication from the hospitals. She told us how helpless she felt. “Not being able to be there, it was the helplessness of not being able to do anything. The loss of control and power, which was really awful.” Cara’s mum died within a week of being in hospital, and her dad died just five days later. The sudden death of both her parents felt ‘surreal’. “It’s sudden, completely unexpected – if it’s caught in hospital, you thought your loved one would be safe, obviously. So, it feels like it was completely avoidable. You’re angry, it’s unjust. And surreal, completely surreal. One minute my parents were fine, living their own life. And the next minute, less than a month later, they’re both dead.” Cara told us how she has been left with an overwhelming sense of guilt, constantly replaying the decisions she made and unanswered questions about what happened. “These ‘what ifs’ play on your mind. Yes. Did you do the right thing by saying, ‘You’ve got to contact the hospital.’ Would they have been better off if they’d just died at home? They suffered in hospital alone. So, all these things play on your mind. You ruminate over this. There’s just so many unanswered questions, you didn’t know what happened in the hospital.” She was left with an intense fear that she might also catch the virus and die. Her feelings were overwhelming and led to thoughts of self-harm and suicide. “The sense of overwhelm that I felt with all of these factors going on, and I was shielding as well. So, I was like, obviously my parents died from Covid, and I’m terrified of catching anything. I did have thoughts of suicide and self-harm. I’d never in my life experienced thoughts of self-harm, it was incredibly scary.” Cara told us how she has felt unable to process her grief. “It feels like my parents could just still be living out there somewhere … I’m still stuck in, like, a long state of bereavement … I mean, I can get on with day-to-day life but when I think about everything that’s happened and trying to find out what went on, going through hospital complaints, getting records, reading medical notes. I was all caught up in that for maybe 2 years … And when they went did I grieve? I don’t know. Have I? I’m not sure.” |

Contributors had to deal with numerous practical and administrative tasks following the death of their loved ones at a time when organisations were struggling to cope with the impact of the pandemic. This added further pain, frustration and difficulty to their bereavement.

For example, many family members had to collect their loved ones’ belongings from hospitals, hospices or their loved one’s care home. This was sometimes done in an impersonal and insensitive way because of pandemic restrictions. This was distressing for bereaved families already struggling with the shock of their grief.

| " | Staff made me pack all her belongings in carrier bags and take them away while she was still lying in the bed dead. They said that normally they would do this, and the relative could return when they were ready to collect belongings, but because of the lockdown I wouldn’t be able to return later.”

– Bereaved daughter, England |

| " | After his passing, I had made it clear to staff that I wanted all of my husband’s belongings returned to me. However, this was not the case and after many phone calls from both myself and the undertaker, I did not receive them for three weeks. When I got them, there were many items missing and damaged. These were all part of my husband and I still feel that I have left part of him behind. After making numerous enquiries, I eventually discovered that there was no inventory of his belongings when he came into the hospital.”

– Bereaved wife, Northern Ireland |

Contributors told us how closing bank, utility and other accounts felt unreal in the wider context of the pandemic, with many services closed and contributors feeling lonely and isolated. Many struggled to accept that the death of their loved ones had really happened. For some, carrying out these tasks felt like part of the process of losing their loved one.

| " | For me, the hard thing was actually picking up the phone and shutting down all the accounts … I almost felt I was complicit in their death, and then I felt their deaths were unnecessary, and I was trying to fight that. But at the same time, I was having to go along with it and shut them down and close them down like they never existed … That was a real, personal struggle for me, was to shut their lives down, where I kind of felt their lives perhaps weren’t ready to end. Do you know, it was quite hard.”

– শোকাহত পরিবারের সদস্য, ওয়েলস |

Other bereaved people faced practical problems getting access to the right information and finding someone to speak to about how to deal with administrative tasks.

| " | Because, you weren’t allowed to leave home, trying to get access, you know, all the stuff that you have to do when someone dies. So, there was all that that needed to be done, but nobody could be contacted because everybody was working from home. And, so none of the documentation was available. It was really chaotic. You know, trying to get access to bank accounts was completely chaotic.”

– Bereaved wife, England |

Having to repeatedly answer questions and share details of their loved one’s death was deeply frustrating.

| " | [When you call organisations to let them know about their death] the first thing they say, ‘We need to go through security, what’s the date of death?’ You could ask me anything, why are you asking me that? Why are you asking me to say that each time I phone you … when they report the death, you should say, ‘In the future, we will ask for the date of death as a security, unless you opt for something else.’ Just put that adjustment in place. None of them would do it. And these were specialist bereavement lines.”

– Bereaved daughter, Wales |

Contributors shared how companies often did not treat them with understanding and empathy. Some experienced insensitive and upsetting conversations with staff and problems dealing with administrative processes after the death of their loved one.

| " | There needs to be more empathy from businesses and companies who are dealing with this … when I had that first call and she asked [my husband’s age] and stuff like that, and she was like, ‘I haven’t had one that young from the pandemic yet.’ … There was no support or empathy … I remember her saying, ‘So, he was 45 and no medical conditions? That’s incredibly rare.’ I was like, ‘I don’t care, this is my husband and my family that has been torn apart, and you can’t even be empathetic.’”

– Bereaved wife, England |

Reflections from Bereaved Listening Events

Bereaved contributors at the reflective workshops emphasised how disappointed and angry they were that businesses like banks and utility companies did not recognise the unique challenges of pandemic bereavement. Contributors said they wanted them to improve how they support bereaved people in future pandemics.

“I think there’s a real message for businesses … they really need to up their game, because you’re trying to tell them what’s happened and so on, it’s so distressing. They are not trained. It would be easy to train a proper bereavement service they’re in, and the banks were hit or miss.” Bereaved daughter and wife, Scotland

They also shared examples of organisations that were more supportive and did their best in a difficult situation, particularly when they provided a consistent contact to help people carry out the necessary tasks. However, bereaved people were deeply upset by the insensitive and dismissive approach taken by many organisations.

“After any bereavement, there is a lot of bereavement admin that has to be done. Things like the utility companies, pensions, all of that kind of stuff. That’s hard to do at the best of times, it’s not easy, but in the pandemic, it was just so much harder. I was having to deal with it all on behalf of my mum, who just couldn’t deal with it and had not dealt with any of the admin in her marriage to my dad, and she was 100 miles away … Some companies were really good. Some companies had designated people, it was easy to find out who to contact, numbers and stuff like that. But others, they were just not prepared at all. Some of them, you felt were actually being obstructive … they were insisting that the criteria that existed in normal times had to be followed. Like we had to have this paperwork and things like that and when you can’t access any of it there was no flexibility.” Bereaved son, England

3 Impact on funerals, burials, cremations and other end of life ceremonies

This chapter explores how the pandemic affected funerals, burials, cremations and other end of life ceremonies and the profound impact this had on bereaved people. Restrictions meant that many had little control over how they could say goodbye, leaving them unable to honour their loved ones in accordance with their beliefs and traditions. Bereaved people said these experiences prolonged and complicated their grief.

Impact of delays and backlogs

The worry and strain caused by delays and uncertainty around planning funerals, burials, cremations and end of life ceremonies was deeply painful for contributors. Many did not know when or whether they would be able to see their loved one’s body or hold funerals, burials, cremations or other end of life ceremonies. The bodies of their loved ones were often in mortuaries for several weeks and there were delays to issuing death certificates. This meant they had to wait to arrange funerals, burials, cremations and other end of life ceremonies.

| " | My mother lay in the hospital morgue for five weeks because the funeral parlour was full. I’ll never forget the funeral director who was trying delicately to explain this to me. It was Easter weekend when I was trying to arrange the funeral, and he sounded close to breaking point himself.”

– Bereaved daughter, England |

The impact of delays was especially painful for communities where cultural and religious practices around death are time sensitive. We heard how delays during the pandemic deeply affected Muslim and Jewish communities, preventing them from carrying out traditional burial rituals within the required timeframes.4 For many Muslims, the inability to bury their loved ones quickly, in accordance with their faith, caused intense distress. Jewish families too described the pain of being unable to follow essential practices around death that bring spiritual comfort and closure.

| " | Culturally and religiously you’re meant to be buried within 24 hours of passing away, and returned to the ground, kind of thing, to the earth, but with Covid that totally destroyed all of it, and it affected the Muslim community hugely … [my father’s] funeral was about 2 weeks later, maybe even 2.5 weeks later which is quite shocking, and unusual, and unheard of, and what was happening at that time is that there were loads of bodies just in, I guess, morgues.”

– Bereaved daughter, England |

Contributors told us how delays in accessing death certificates caused immense strain for many families. Many services were operating virtually and at reduced capacity, making it challenging to certify their loved one’s death.

| " | It was so difficult to [get] the death certificate for my mother … there was a query over the death certificate with two doctors refusing to sign [it] – before a junior was persuaded to help release mum for me … it was a horrific experience.”

– Bereaved daughter, Northern Ireland |

Chasing for updates often fell to bereaved people themselves. This added a frustrating and exhausting administrative process at a time of devastating loss and while people were still trying to process their grief.

| " | So, we had announced within the community that, [my uncle] had passed away… people were, you know, going to the mosque to offer their condolences, do prayers for him and stuff like that. But we weren’t able to obviously put him to rest, put ourselves to rest, so to speak … It was a very daunting three weeks. For, like, three weeks, just constantly chasing, chasing, chasing, trying to get the death certificate. So, it was very tiresome. It was a testing time as well, emotions were a bit all over the place.”

– Bereaved nephew, England |

We heard about the challenges at the beginning of the pandemic in the care and preparation of those who died. There was a lack of understanding as to the safe handling of the bodies of people who died due to Covid-19.

| " | It was the early days of Covid and although grandad didn’t appear to have died of Covid no one seemed to know how to handle the bodies of Covid patients or even which ones were Covid patients.”

– Bereaved granddaughter, England |

Some people told us they had to join long waiting lists for their loved ones to be cremated or buried. In some cases, contributors felt they had no choice but to bury their loved one in a different cemetery or have a cremation instead. This was deeply upsetting for many. They felt they were unable to hold a funeral or other end of life ceremony that was not in line with their or their loved ones wishes.

| " | The cemetery [all our family are buried in] … They wanted a burial I think at first, the burials were taking about 4 or 5 weeks. In the end they had the cremation, which was not their initial choice … the family were really upset by that, but they didn’t want to keep the body in the freezer for any longer than it had to [be there].”

– Bereaved niece, England |

| " | There was a delay with the cremation as well. So, she had died, I’m trying to think, so it was end of February 2021 … she went into hospital, a few days later, she had died. My mum contacted the funeral director and they had advised that it was a 3-week wait, if not a bit longer. So, it ended up being 3 and a half weeks after she had actually died when she actually got cremated.”

– Bereaved grandson, Scotland |

Reflections from Bereaved Listening Events

Bereaved people discussed the delays they faced planning funerals for their loved ones during the pandemic. They felt the country was unprepared for the scale of deaths, with undertakers and funeral directors left overwhelmed. These backlogs often left families and friends with little choice in decisions about honouring their loved ones.

“I just think as a country we were totally unprepared and the undertakers were obviously dealing with, I know this is horrible to say, high volumes of deaths from Covid. What they were getting over a weekend is something they would get over a far longer period of time … I just felt there were just so many people dying [the funeral] wasn’t as personalised I think, as what it could’ve been.” Bereaved daughter, Scotland

Impact on loved ones planning funerals or other end of life ceremonies

Experiences of planning funerals, burials, cremations and other end of life ceremonies during the pandemic

During the pandemic, the burden of planning funerals, burials, cremations or other end of life ceremonies frequently fell to a single family member, friend or a small group of relatives. They were often required to liaise with funeral services remotely, without their support networks and relationships. Family members and friends who took on this responsibility said they felt deeply isolated. They found the task of navigating restrictions, speaking to funeral directors and organising a service alone was time-consuming, draining and painful.

| " | So, all communication was by telephone. Everything, undertakers, registry office to register the death, everything. I didn’t leave my seat, I felt, for weeks [I was] just trying to organise everything. Contacting [my husband’s] family in Greece. Other friends, family elsewhere and it was horrendous.”

– Bereaved wife, England |

The lack of face to face meetings and interactions also made it harder for some people to develop a relationship with funeral directors and share stories of their loved one and their wishes for their burial or end of life ceremony.

| " | All the funeral planning via phone, you know, so it’s part of grief processing, isn’t it, to meet someone and go through slowly in terms of what their wishes are and stuff. So, none of that.”

- শোকাহত পরিবারের সদস্য, ইংল্যান্ড |

Some bereaved people gave examples of how funeral directors made huge efforts to do everything they could to honour their loved one’s wishes and hold funerals, burials, cremations and other end of life ceremonies in ways that were suitable for families. They said funeral directors provided emotional support as they prepared for the funeral. They also gave examples of funeral directors adjusting pre-paid funeral plans to better suit the pandemic circumstances. Funeral directors going out of their way to support bereaved people helped them with their grief and provided a sense of human connection while they were trying to navigate confusing and impersonal processes.

| " | The funeral director involved went above and beyond, she contacted me every day and was the epitome of caring.”

– Bereaved niece, Northern Ireland |

| " | I have to say that the funeral arrangers were absolutely brilliant. I told them the story of my husband leaving the house and wanting to come home but he couldn’t because it was Covid etc. We lived in a very narrow drive, because it was a cottage, and the funeral directors moved this great big hearse, backed it all the way up the lane so that my husband could actually go from his house which was so touching for me. It was probably, in the whole of this, the only touching thing that actually happened.”

– Bereaved wife, England |

| " | Because my parents had prearranged funeral plans and they assumed they were going at different times, they’d said, ‘Right, we want 1 hearse and a car to follow.’ But, of course, we just needed 3 cars, 2 hearses and 1 car to follow. So, [the funeral directors] said, ‘We’ll refund you the car.’ They were so caring, and when you’re at the most vulnerable, they weren’t trying to, sort of, take advantage. They were trying to, sort of, help and support.”

– Bereaved daughter, Wales |

| " | The funeral director involved went above and beyond, she contacted me every day and was the epitome of caring.”

– Bereaved niece, Northern Ireland |

Changing restrictions for funerals, burials, cremations and other end of life ceremonies

Throughout the pandemic, the restrictions that applied to funerals, burials, cremations and other end of life ceremonies changed quickly with limited notice and were different in different parts of the country. Changing guidance on social distancing and how many people could attend created confusion and frustration for contributors. Many had to make last minute changes to the plans they had made to mark the death of their loved ones.

| " | One of the issues was about how the restrictions kept changing all the time and sometimes they would change between making the arrangements. You’ve got one thing planned and then, suddenly, they were changed, and you couldn’t do what had originally been planned.”

– Bereaved son, England |

| " | On the day before the funeral the government changed lockdown rules affecting the funeral location. All hotels and B&Bs interpreted the rules as not being able to open, so all bookings were cancelled. The venues for a small wake afterwards [were] also cancelled. It was incredibly stressful trying to find solutions to the various issues raised by the change of rules at short notice.”

– Bereaved friend, England |

Jane’s storyJane’s husband had cancer and caught Covid-19 during the pandemic. The last time she saw him in person was when he was taken away in an ambulance. She was not able to visit him in the hospice where he died. “[My memory] is an image, and it’s the look on my husband’s face as he was taken away in an ambulance. Because, I think, he knew by the look on my face, it was probably the last time we’d see each other.” Jane spoke about the difficulties she faced trying to organise her husband’s funeral because many more funerals than usual were taking place. “We struggled to actually get a vicar because they were so busy, so we struggled to get the vicar we actually wanted for his service which I ended up doing by more likely pleading and bribing.” The lack of choice around what could happen during the funeral added to her grief and sadness. “There was no singing. My husband loved singing in church and everything like that but none of us were allowed to sing. We had to listen to music.” The restrictions on the number of people who could attend funerals meant that some family members were not able to come. “My family, I don’t live anywhere near my family. They are scattered from, you know, Yorkshire down to Plymouth so none of those could come to the funeral because we were so restricted on numbers.” Changing restrictions also meant that she had to struggle to find flowers for the funeral at the last minute. “The day before the funeral, we were not allowed flowers and then the day of the funeral they said we could get flowers, so I scrabbled all morning of the funeral trying to get some flowers organised for my husband’s funeral.” |

Reflections from Bereaved Listening Events

Bereaved contributors emphasised how challenging it was to navigate frequently changing guidance during the pandemic. Changes to restrictions, sometimes up until the day of the funeral, led to uncertainty, stress and guilt. They wanted to see more consistency in the future.

“The change of restrictions and not knowing what was happening. When we actually arrived at the funeral, even then it was changed on the day … So, just making sure that if this happens again, that there’s consistency and that things are changed, just because the slightest alteration when you’re in that state of grief, it’s just another stress, another worry.” Bereaved daughter, England

Financial impact of funerals, burials, cremations and other end of life ceremonies

The sudden death of a loved one from Covid-19 brought unexpected funeral costs that many families had not planned for. These expenses added financial worries, stress and guilt, where money had to be borrowed from friends and family. They often had to use savings or use credit cards and loans to cover funeral costs. Meanwhile, bereaved people were trying to process their grief.

| " | Usually when someone falls ill you prepare yourself. I wasn’t prepared for this at all. And obviously I had to pay for, like, the whole funeral arrangement, undertaker, everything, the hearse. Just costs came left, right and centre that I didn’t know I’d have to pay for … I had a household to run as well.”

– Bereaved nephew, England |

Jack’s storyJack’s father-in-law was admitted to hospital with Covid-19 and unexpectedly died there a short time later. The shock of his sudden death left the family having to arrange his funeral and also without any knowledge if he had left financial arrangements in place for it. “Our family life was turned upside down immediately as my wife had to deal with the fallout of her father’s death, arranging funeral plans for him.” “The whole process just seemed very upsetting for her and our family. We had to take a loan out to pay for the funeral at the time which also added to the financial stress as everything happened so quickly and we were unsure if there was anything in place to cover the funeral costs.” |

Other bereaved people told us how families, friends and communities came together and supported each other to help with funeral costs. In some cases, we heard how bereaved friends and family organised fundraisers or received donations to pay the expenses. This helped alleviate some of the financial pressure and strain bereaved people felt.

| " | The mercy of the timing of [my friend’s] death was that he was able to have a funeral. All his friends chipped in to raise money for his funeral, and in the end there was more than enough, and the extra got donated to a charity.”

– Bereaved friend, England |

| " | [To] pay for the funeral, my sister-in-law did one of those GoFundMe pages. It raised £11,000, and the funeral cost £6,500. So, that paid [for the funeral]. I don’t know what we’d have done [without that].”

– Bereaved wife, England |

Deciding who could attend

Restrictions on the number of people who could attend funerals, burials, cremations and other end of life ceremonies was sometimes a source of conflict and strained relationships between family and friends. Contributors were forced to make painful choices about who could attend, which was deeply upsetting for already grieving families.

| " | People were fighting to go to the funeral, ‘What makes this person to go to the funeral and not me?’ So, now it was becoming World War Three in your own house, you get what I’m saying, yes. So, there was quite some tension, because people were saying the ones that went are your favourites, ‘So, you favoured A, B, C and you forgot me, so why do you need me? Why are you calling me?’ So, it caused division in the family as well.”

– Bereaved cousin, England |

Some people told us how they sacrificed their own attendance at loved ones’ funeral, burial, cremation or other end of life ceremony so others could go.

| " | I wasn’t able to attend the funeral, because at that time, I think they were saying it was 10 people. So, I said, ‘By the time you have the wife, his children, their partners, their grandchildren.’ So, I said to her, ‘No, that’s fine.’”

– Bereaved cousin, England |

| " | The lack of a family funeral [for my father] caused real hardship and arguments to his many children, grandchildren and brothers.”

– Bereaved daughter, Wales |

Lack of choice and control

Bereaved individuals reflected on the lack of choice they were given to make fundamental decisions about honouring and remembering their loved ones, leaving them feeling powerless and often despairing. In many cases, families and friends were not able to choose the clothing or casket their loved one was buried in or the venue for the funeral.

| " | There was just no choice. You just had to do what you could do with a really dreadful set of circumstances but, you know, the idea, I remember asking or saying, ‘Well, I think I would quite like that for the coffin’, and the undertaker just looking at me and saying there wasn’t a choice.”

– Bereaved daughter, Scotland |

| " | With my grandad we couldn’t even put any clothes on him, he was just wrapped around a rag and put in a box, and that, you know, was very hard, because then you’d want to, say, at least get clothing for your loved one for the last time before they get buried. You want them to be buried, probably, wearing, like, a shirt and tie, or something like that. A suit or something.”

– Bereaved grandson, England |

| " | My dad was buried in his pyjamas just as he died. He was put into the body bag and that’s the way he was buried, and it was the same with my husband … he arrived for burial in a sealed bag for the prevention, I think, of the virus.”

– Bereaved daughter and wife, Scotland |

We also heard how some people could not see their loved one’s body ahead of the funeral, burial cremation or other end of life ceremony. When loved ones had died alone or with only a few visitors, not being able to see the body meant some people were left in disbelief or denial about the death, making it even harder to accept what had happened.

| " | They told me that I couldn’t see [my husband] in the hospital. He was going into a body bag, straight to the undertaker. I asked the undertaker and, in fairness, with the undertaker I said to him, ‘Oh, what do you need, like, dress-wise?’ And he said, ‘Well, he’s got to stay in the gown that he died in. We’re not allowed to open up the body bag, so his body bag’s gone straight in the coffin.’ So, I wasn’t allowed to see him and, to be honest with you, even now sometimes it’s like, I know this might actually sound absolutely crazy, ‘Have they kidnapped him? Has he really gone?’ Because I’ve not gone through that process of seeing the body.”

– Bereaved wife, Wales |

Reflections from Bereaved Listening Events

Contributors also discussed how painful it was that their loved ones did not have funerals, burials, cremations or other end of life ceremonies that were in line with their wishes, religion or cultural heritage.

They emphasised the continuing anguish and regret among bereaved people because there was no way to get these experiences back. They said this has exacerbated their grief and led to feelings of unresolved sadness for many.

“The fundamental thing is that the ones who died didn’t get the funeral they would’ve had under normal circumstances, you know, in terms of what was in the funeral, people who would’ve come and taken part. That was denied [to] them.” Bereaved son, England

Impact of restrictions on funerals, burials, cremations and other end of life ceremonies

The limits on the number of people who could attend funerals, burials, cremations and other end of life ceremonies prevented large gatherings. Travel restrictions within the United Kingdom also meant some bereaved family members could not attend.

| " | My mum was cremated with only five people in attendance …. because of the legally limited attendance requirements, and that fact that her wider family were not able to travel [due to restrictions].”

- Bereaved daughter, Wales |

Others missed funerals, burials, cremations and other end of life ceremonies out of concern of contracting or spreading the virus.

| " | My mum and dad died … I didn’t attend my parents’ funeral which, obviously, [was] devastating. But I was terrified. Both my parents had died, you know, I didn’t want to die either. My sister was definitely adamant that she didn’t want me to attend, she didn’t want to lose me as well because it’s just 4 of us in our family.”

- Bereaved daughter, England |

| " | Well, we just wanted everyone to be safe, so I just felt like me going would not be helpful because there would be no one to look after my children if I did and then, also, I didn’t want to spread infection in case I had it, you know? Because at that time, there weren’t even tests, so no one really knew if they had it or not, the tests came later. There were so many unknowns.”

- Bereaved niece, England |

Not being able to travel together to the funeral, burial, cremation or other end of life ceremony in a car was distressing for some bereaved people. We heard how upsetting and isolating it was having to drive themselves to the funeral, sometimes alone.

| " | We made our own way, because the funeral parlour wouldn’t take us, because, again, 6 people in the car was-, you could meet there as 6 people, but you couldn’t physically go in a car, 6 of them together. Yes, so we had to make our own way, that was another thing.”

- Bereaved nephew, England |

For those who attended funerals and ceremonies, social distancing measures meant mourners were unable to sit together, touch or do simple things like giving family and friends a hug. Contributors said this made funerals, burials, cremations and other end of life ceremonies feel cold and impersonal and meant they did not offer the support and comfort they usually would. Some shared how looking back on the funeral added to the painful memories from the death of their loved one.

| " | Well, owing to the regulations at the time, only householders could sit together at the funeral, with a maximum of two together. That meant I sat on my own through the service, the most painful way of attending your husband’s funeral that I can think of. Again, the word inhumane comes to mind. Even though it took place a month after he died, and I may have seemed strong to others, I was still very much in shock and desperately in need of support during the service, yet nobody could be there for me as they were in their own groups. The ceremony went in a blur and is such a ghastly memory.”

- Bereaved wife, England |

| " | Not even immediate family could go to mum’s funeral, it was such a horrible experience, I hoped my dad’s would be different. I went back to England, then got a call to say come home and it was the worst thing [father dying], I hadn’t even got over my mum, it was terrible. We were isolating, I couldn’t even sit beside my daughter at the funeral. We were told by the chapel that we mustn’t encourage people to come along.”

- Bereaved daughter, Scotland |

One bereaved family member described breaking social distancing rules to support another family member, because they thought it was wrong to prioritise regulations over human compassion in moments of grief.

| " | I wasn’t supposed to comfort my sister-in-law, who was next to me, but she lived alone at the time, apart from her children who weren’t there. We’re sitting in the chapel with the masks on, she’s distraught, she’s falling apart. I’m not going to keep 2 metres away from her, I just couldn’t. It’s a natural human reaction. We’d all just had Covid anyway, I thought. But, we broke the rules doing that, I broke the rules comforting my sister-in-law. It was inhumane.”

- Bereaved daughter-in-law, Scotland |

Mary’s storyMary’s mother contracted Covid-19 and died in hospital during the early stages of the pandemic. Mary had been shielding since the start of the pandemic and her mother’s funeral was the first time Mary experienced social distancing measures. “[The funeral] was slightly weird for me, because when I got to the crematorium, I hadn’t done the whole queueing supermarket thing because I’d been shielding. I hadn’t done the whole 2 metre thing, so my immediate reaction was to shake the vicar’s hand, which of course you’re not allowed to do.” When Mary walked into the crematorium, there was tape over the pews to maintain distance between her and her family members. “The shock of walking in there, there was tape everywhere. When you walked into the crematorium, it was like you were at a road traffic accident, and there was red and white tape everywhere. All the pews were taped up apart from one pew for me and my girls, and one pew the other side for [my sister].” Mary said how unfamiliar and alienating the funeral felt. After isolating alone for months, the lack of physical comfort at her mother’s funeral intensified her feelings of being alone when support was most needed. “The behaviours when you got to the funeral were, kind of, very alien, and it made you feel – I was already isolated at home, hadn’t really left the house since January. So, to have suddenly been put in that position where you can’t shake somebody’s hand and go and talk to them or, you know, have a hug. I needed a hug so badly.” |

Some contributors told us they felt rushed at the funeral, burial, cremation or other end of life ceremony, which meant they did not have proper time to reflect. They thought the increased number of funerals, burials, cremations and other end of life ceremonies meant they were hurried and too short. Some said this added to the sense that their loved one was just ‘one of many’ rather than being treated with the dignity they deserved.

| " | My dad had a direct cremation; they turned up in [a] black van and handed us a shopping bag with a cereal box of ashes and they took a photo of us with it for proof of delivery. It was unbelievable.”

– Bereaved person, Wales |

| " | The amount of diggers that were around … it was a couple of people and the workers, all wearing masks, and they’re trying to be respectful, but you can tell that they just need to move on to the next one, because it’s almost every two minutes, just a horror show really.”

– Bereaved daughter, England |

We heard about the distress caused when people from different religious and cultural faiths could not perform traditional practices at funerals. These included open-casket viewings and placing religious items such as a tallit (Jewish prayer shawl) or symbolic offerings like garlands and incense (Hindu) with their loved ones.

| " | It’d be different because we could say goodbye together, see [my husband] go, couldn’t we … At least if you can see him go, say goodbye, my house would be more peaceful than if we don’t see him … A Hong Kong funeral [for my husband] was organised here, but I can’t see the body. I was upset about that … In a normal process, they would open the coffin and then people can walk around in a circle and say goodbye. This is part of the ritual.”

– Bereaved wife, England |

| " | The one thing I do know is we didn’t give [dad] his tallit.5 We didn’t bury him with his tallit. And I’ve got his tallit and it, kind of, it’s both lovely that I’ve got his tallit, but it’s also awful that I’ve got his tallit because it shouldn’t be with me. It should be with him. And that would have mattered to him.”

– Bereaved daughter, England |

| " | We put certain things into the coffin, like coconuts and garlands and incense and things like that. All symbolising things for their journey to move on smoothly. In these cases, the coffins couldn’t be opened, because we weren’t allowed. It was only immediate family that could attend, so that was really hard. I know for my Auntie and for us, it broke our hearts to see her in that state that she couldn’t do the final farewell as she wanted to.”

– Bereaved niece, England |